73,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

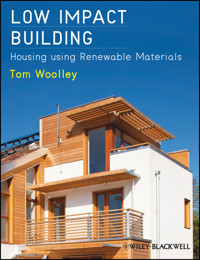

This guide to the designs, technologies and materials that really make green buildings work will help architects, specifiers and clients make informed choices, based on reliable technical information.

Low Impact Building: Housing using Renewable Materials is about changing the way we build houses to reduce their ‘carbon’ footprint and to minimise environmental damage. One of the ways this can be done is by reducing the energy and environmental impact of the materials and resources used to construct buildings by choosing alternative products and systems. In particular, we need to recognise the potential for using natural and renewable construction materials as a way to reduce both carbon emissions but also build in a more benign and healthy way. This book is an account of some attempts to introduce this into mainstream house construction and the problems and obstacles that need to be overcome to gain wider acceptance of genuinely environmental construction methods.

The book explores the nature of renewable materials in depth: where do they come from, what are they made of and how do they get into the construction supply chain? The difference between artisan and self-build materials like earth and straw, and more highly processed and manufactured products such as wood fibre insulation boards is explored.

The author then gives an account of the Renewable House Programme in the UK explaining how it came about and how it was funded and managed by Government agencies. He analyses 12 case studies of projects from the Programme, setting out the design and methods of construction, buildability, environmental assessment tools used in the design, performance in terms of energy, air tightness, carbon footprint and post-occupancy issues.

The policy context of energy and sustainability in the UK, Europe and the rest of the world is subjected to a critical examination to show how this affects the use of natural and renewable materials in the market for insulation and other construction materials. The debate over energy usage and embodied energy is discussed, as this is central to the reason why even many environmentally progressive people ignore the case for natural and renewable materials.

The book offers a discussion of building physics and science, considering energy performance, moisture, durability, health and similar issues. A critical evaluation of assessment, accreditation and labelling of materials and green buildings is central to this as well as a review of some of the key research in the field.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 422

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

Contents

Acknowledgements

Information and assistance was kindly provided by:

Figure credits

Introduction

The Renewable House Programme

The expansion of natural building

The wider environmental agenda

Chapter overview

1 Renewable and non-renewable materials

Synthetic, manmade materials

Limitations of synthetic materials

Questioning claims about recycling

Resource consumption problem with synthetic materials

Renewable materials – insulation

Carbon sequestration and embodied energy

Performance and Durability of natural materials

Natural renewable materials commercially available

Low impact materials

2 Case Studies: twelve projects in the Renewable House Programme

Abertridwr: Y Llaethdy South Wales:sheep’s wool insulation

Drumalla House, Carnlough, County Antrim: Hemcrete and sheep’s woolrim

Blackditch, Stanton Harcourt, Oxfordshire: Hemcrete and hemp fibre insulation

Callowlands, Watford: Hemcrete

Domary Court, York: Hemcrete

Inverness: CLT and fibre insulation

Long Meadow, Denmark Lane, Diss: Hemcrete and Breathe hemp flax insulation

LILAC, Leeds: Modcell strawbale

Tomorrow’s Garden City, Letchworth: wood fibre and Hemcrete

Reed Street, South Shields: wood fibre and stone wool

The Triangle, Swindon: Hemcrete and hemp insulation

Pittenweem: no renewable insulation materials

3 The Renewable House Programme: a strange procurement!

Monitoring and evaluation

4 Analysis of issues arising from the case studies

Success in using natural renewable materials

Adapting conventional timber frame construction for using natural materials

The importance of getting details right and using detailsappropriate for eco materials

Problems with designs and the need to get warrantyapprovals for changes of details

Weather issues and hempcrete

Decision of Lime Technology to go for prefabrication in future and whether this is the best option

Using wood fibre products and issues related to construction and components

5 Attitudes to renewable materials, energy issues and the policy context

Why attitudes and policies affect the use of renewable materials

Climate change and energy efficiency targets

What is carbon?

Sustainable construction and energy policies

UK Code for Sustainable Homes

New planning policy framework

The zero carbon myth

The carbon spike concept

Energy in use or ‘operational energy’ is all that matters to many

How embodied energy is discounted

Carbon footprinting

Passive design approaches

Do natural and renewable materials have lower embodied energy?

Carbon sequestration in timber

Wood transport issues

Carbon sequestration in hemp and hempcrete

The Green Deal

Official promotion of synthetic insulations

Other attitudes hostile to natural materials – the food crops argument

Transport and localism

Cost

6 Building physics, natural materials and policy issues

Holistic design

European standards, trade and professional organisations

Building physics – lack of good research and education

Lack of data and good research on sustainable buildings

Energy simulation and calculation tools

Assessment of material‘s environmental impact and performance

Moisture and breathability and thermal mass

Breathability

Thermal mass and energy performance in buildings

Building physics research into hempcrete

Indoor air quality

7 Other solutions for low energy housing

Hemp lime houses

Hemp houses in Ireland

Local sheep’s wool in Scotland

Strawbale houses in West Grove, Martin, North Kesteven, Lincolnshire

Timber experiments

Scottish Housing Expo

Using local materials?

Greenwash projects?

So-called ‘carbon neutral’ developments

Earth sheltered building

BRE Innovation Park

Masonry construction for low energy houses

Blaming the occupants

Back to the 60s and 70s – déjà vu

8 A future for renewable materials?

Middlemen

Postscript

Glossary/Abbreviations

Index

Other Books Available from Wiley-Blackwell

Advertisement

This edition first published 2013© 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd

Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell.

Registered OfficeJohn Wiley & Sons, Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex,PO19 8SQ, UK

Editorial Offices9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UKThe Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK2121 State Avenue, Ames, Iowa 50014-8300, USA

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell.

The right of the author to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author(s) have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with the respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services and neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for damages arising herefrom. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Woolley, Tom, author.Low impact housing : building with renewable materials / by Tom Woolley. pages cmIncludes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4443-3660-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Ecological houses.2. Building materials–Environmental aspects. 3. Green products. 4. Recycled products. I. Title.TH4860.W67 2013690.028′6–dc23

2012031588

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Cover design by His and Hers Design.Front cover: Tomorrow’s Garden City, Letchworth © Morley von Sternbergwww.vonsternberg.com.Back cover: Drumalla Park, Carnlough, courtesy of Brian Rankin, Oaklee Homes Group.

For the pioneers of natural and renewable construction materials

Acknowledgements

There are many people who have assisted in the production of this book and I hope not too many have been overlooked. In particular it would not have been possible without the help of: Rachel Bevan, Leonie Erbsloh, Graeme North, Madeleine Metcalfe and Beth Edgar (Wiley-Blackwell); Gary Newman, Neil May, Alison Pooley, Ceri Loxton, Rob Elias, Jack Goulding (University of Central Lancashire); John Littlewood, Nigel Curry and the Technology Strategy Board Energy Efficient Bio-based Natural Fibre Insulation Project group.

Information and assistance was kindly provided by:

Alliance for Sustainable Building Products

Iris Anderson

Carol Atkinson

Russell Ayres

John Bedford

Matt Bridgestock

Luke Brooker

Peter Burros

James Byrne

Jim Carfrae

Peter Chalkley

Paul Chatterton

Michael Cramp

Robert Delius

Cathie Eberlin

Andrew Evans

Frances Geary

Jonathan Gibson

John Gilbert

Steve Goodhew

Tracy Gordon

Sahra Gott

Paul Green

Keeley Hale

Mike Haynes

Wai Lun Ho

Glen Howells

Nigel Ingram

Muzinee Kistenfeger

Simon Lawrence

Stephen Lawson

Niall Leahy

Bobby Leighton

Simon Linford

Donald Lockhart

Dave Mayle

Donal MacRandal

Kevin McCloud

Gerry McGuigan

Eamon McKay

Claire Morrall

Carl Mulkern

Daniel Mulligan

Niall Murtagh

Clinton Mysleyko

Natureplus

Tony Nuttall

Mark Patten

Robert Pearson

Gina Pelham

Brendan Power

Ian Pritchett

Paul Raftery

Brian Rankin

Jimm Reed

John Retchless

Frank Reynolds

Haf Roberts

Francois Samuel

Peter Seaborne

David Tibbs

Julie Watson

Darren Watts

Byron Way

Craig White

Jayne Wilder

John Williams

Keith Wood

Louisa Yallop

Myles Yallop

Marissa Yeoman

Gary Young

Figure credits

Figure 1.1

www.stonebase.com

, CONSARC

Figure 2.5

Greenhill Construction

Figure 2.11

Oaklee Housing Association

Figure 2.12

Oaklee Housing Association

Figure 2.17

Cottsway Housing Association

Figure 2.19

Luke Brooker Airey Miller Partnership

Figure 2.20

Luke Brooker Airey Miller Partnership

Figure 2.21

Luke Brooker Airey Miller Partnership

Figure 2.26

John Gilbert Architect

Figure 2.27

John Gilbert Architect

Figure 2.28

John Gilbert Architect

Figure 2.29

John Gilbert Architect

Figure 2.35

White Design

Figure 2.36

Paul Chatterton, LILAC

Figure 2.40

The Limecrete Company Ltd.

Figure 2.41

The Limecrete Company Ltd

Figure 2.42

Tony Nuttall Architect8

Figure 2.43

Tony Nuttall Architect8

Figure 2.44

Tony Nuttall Architect8

Figure 2.45

Robert Delius Stride Treglown

Figure 2.49

Clinton Mysleyko Fitz Architects

Figure 2.50

Clinton Mysleyko Fitz Architects

Figure 2.51

Glen Howells Architects

Figure 2.52

Glen Howells Architects

Figure 2.56

Glen Howells Architects

Figure 2.57

Glen Howells Architects

Figure 2.58

Glen Howells Architects

Figure 5.2

Sustainable Homes

Figure 5.3

Based on diagram from Jukka Heinonen

Figure 7.1

Hemporium South Africa

Figure 7.2

Hemporium South Africa

Figure 7.3

Brendan Power

Figure 7.4

James Byrne

Figure 7.5

Sleaford Standard

Figure 7.6

Parsons and Whittley Architects

Figure 7.7

Helen McAteer Menter Siabod Ltd

Figure 7.10

The Accord Group

Figure 7.11

The Accord Group

Introduction

Sustainability is not about energy, composting or insulation. Sustainability is nothing more than leaving the world a little richer than you found it.

(Watkins 2009)

This book is about changing the way we construct buildings and houses to reduce their carbon footprint and to minimise environmental damage. One of the ways this can be done is by reducing the energy and environmental impact of the materials and resources we use to construct buildings by using alternative products and systems. In particular, we need to recognise the potential for using natural and renewable construction materials as a way to reduce carbon emissions and also build in a more benign and healthy way. This book is an account of some attempts to introduce this into mainstream house construction in the UK, and the problems and obstacles that need to be overcome to gain wider acceptance of genuinely environmental construction methods.

Natural and renewable building and insulation materials can be made from biological sources such as hemp, flax, wood, straw, sheep’s wool and so on. They can be combined with benign or low impact materials, such as lime and earth, into composites. Many building problems can be solved by using these materials, opening the possibility of significant benefits in terms of less pollution, less energy used, better and healthier buildings. Advocates of natural and renewable materials include those who just see a business opportunity in a new market for environmentally friendly products but others embrace Tony Watkins’ holistic philosophy and see the use of natural materials as enriching a more holistic approach to living.

Many think of natural and renewable materials using hemp, earth, lime and so on as a fringe activity, only relevant to self-builders in the countryside using ‘handmade’ approaches (Olsen 2012). This was a frequent criticism of the book Natural Building (Woolley 2006). There have been, and continue to be, pioneers of low impact ways of building and ‘handmade houses’ such as in eco-villages like the Lammas project in Wales (Lammas 2012). With the support of Welsh Government planning policies, people who want to live in a sustainable and self-sufficient way, have been given permission to build houses in the countryside, where normally such development might not be allowed. They have used a variety of low impact building methods and in many cases are ‘off-grid’ so their energy consumption and environmental impact is very low. Despite this they have run into difficulties with the authorities, as their natural earth and timber structures do not comply with energy efficiency and building regulations (Dale and Saville 2012).

Regulations intended to force mainstream builders and developers to reduce energy wastage, are instead used against those whose aim in life is to do exactly that. Such are the contradictions of current policies as they fail to adopt a holistic approach. Instead, as will be argued in this book, policies have tended to support expensive technological solutions and the use of synthetic petrochemical based materials rather than low impact solutions.

On the other hand there has been some progress in recent years for alternative ecological materials and methods of building to become accepted in the mainstream as solutions for public sector bodies, housing associations and even major businesses. These clients and their architects have taken a decision to explore alternatives to petrochemical based synthetic materials, often in contradiction to official policy and this gives hope that environmentally responsible measures will become more widely adopted in the future. Manufacturers and distributors of ecological products have begun to escape from the ‘green ghetto’ and become accepted as part of normal building practice.

Resistance to this ecological innovation remains however. Even campaigners for greener solutions can be hostile to natural materials and fail to understand the importance of low impact solutions. The majority of men (and it is mostly men) working in this sector get caught up in thinking that the only answers is to be found in manmade, synthetic, ‘high-tech’ and mechanical solutions to all the problems. Often these solutions use more energy to create than they will save over the next 20 or 30 years, but their advocates are blind to this. This approach is preoccupied with saving operational energy and ignores embodied energy. Ignoring the energy consumed to solve the problems can make the problem worse not better.

Even more worrying is that many of the conventional solutions to energy efficient buildings, and houses in particular, are using technological solutions that are mistaken and may fail or cause serious problems in the future. Super-insulated and so-called passive house buildings, using synthetic manmade materials, could be creating health problems and are dependent on mechanical solutions to try and mitigate problems of condensation and dampness. Problems of indoor air quality and the toxicity of materials are swept under the carpet in building systems that, when tested, fail to come anywhere near meeting the energy standards that are predicted. This is a scandal and it needs to be exposed, though it will need further research and more detailed analysis of failures, beyond what was possible in this book.

What is particularly frustrating is that alternative and much better systems of construction using natural and renewable materials are available, and far more investment should be directed to developing these materials and systems. Much more needs to be done to support the production of low impact materials at a local level in both developed and developing countries. Unfortunately the emerging economies seem envious of expensive high-tech resource-wasting solutions in the West and see low impact approaches as turning the clock back. Large and powerful multinational companies, who consume a lot of energy producing synthetic materials, and their trade associations, have much more influence over government and international policies. Ultimately this is a political issue and governments need to introduce much more stringent environmental and health limits to ensure that benign methods and materials predominate.

The Renewable House Programme

Central to this book is an account of a programme funded by the UK Labour Government (2007–2010) to encourage the use of natural renewable materials in social housing construction; this became known as the Renewable House Programme (RHP). Twelve projects were funded with varying levels of subsidy, leading to the construction of approximately 200 houses. The book contains twelve case studies providing an insight into the pros and cons of using innovative natural renewable materials in mainstream construction.

The case studies give some indication of how architects, specifiers, clients, builders and insurers operate, in the choice of materials and construction techniques. The construction industry in the UK and most parts of the world tends not favour natural building solutions, so there were many problems coming to terms with an alternative approach. Technical problems are apparent but none were serious enough to completely undermine confidence in the materials and techniques. Despite the requirements of the special government funding to use renewable materials, particularly insulation, many of the projects substituted synthetic materials for part of the construction and one did not use any renewable insulation materials at all! On the other hand, many agencies and individuals involved were happy to use unfamiliar techniques and renewable materials and had surprisingly few problems in substituting them or including them in the designs and construction. Many lessons were learned from these projects, and while more will become apparent as monitoring and evaluation take place over the next few years, there is enough information to influence how the natural renewable materials market moves forward.

When this review of the case studies began in 2010 it seemed feasible to complete it within 18 months, as government funding requirements meant that the projects had to be completed by April 2010. However, at the time of writing (spring 2012), some of the projects were still under construction and some had only just started. The delays were largely due to issues other than the use of natural materials.

The expansion of natural building

Since Natural Building (Woolley 2006) and Hemp Lime Construction (Bevan 2008) were published, many more UK projects have been built using natural and renewable materials. Apart from numerous housing projects, there have been significant commercial, industrial and leisure buildings that have used hemp and other natural materials. Hempcrete construction, for instance, has been used in numerous food and wine storage warehouses and a large superstore in Cheshire for Marks and Spencer.

The difficulties and problems associated with introducing sustainable approaches to the mainstream construction and house building industry are wide-ranging. Thus, in addition to the 12 RHP projects, the book includes a chapter highlighting some other interesting housing projects that were not part of the RHP but have used innovative construction approaches both natural and synthetic petrochemical.

The book also includes chapters that deal with the many questions surrounding energy efficient building construction. These include the nature and range of natural materials available, supply chain and sourcing issues, legislation, building regulations, environmental policies and building physics. The science of natural materials is very different from that of synthetic petrochemical based materials, particularly in terms of thermal performance, moisture management and durability. Buildability, design and detailing issues also vary. Finally, there are the attitudes of all the different players towards natural materials and how they are reacting to energy efficient and innovative houses. The book concludes with an brief appraisal of the likely future for natural and renewable materials both in the UK and internationally.

The wider environmental agenda

Deeply embedded in the idea of using low impact materials, should be the aim of helping humanity survive the many environmental crises that face us. Yet it is disturbing how many people are in a state of denial about the real dangers. For the head-in-the-sand group, energy efficiency is simply seen as a way to cut running costs, whatever the environmental impact, or to display wealth through expensive and ostentatious renewable energy arrays and wind turbines. In a recent discussion with someone who wanted a new house designed, when asked if they were interested in an environmentally friendly design, they replied that they wanted the house to be energy efficient, but they didn’t want it to be environmentally friendly! This is an indication of the major attitudinal problem that needs to be overcome before materials that are better for health and the planet are readily adopted by society.

One of the difficulties in advancing renewable and natural materials is that they can no longer be perceived as fringe to the main construction industry. Those who produce natural, renewable and alternative materials must have a sound economic basis for their products and must engage with normal capitalist business approaches to get their products to market. This has happened quite successfully in Germany and some other European countries, though the market share for environmental products is still quite small. Market pressures can lead producers into business relationships with investors and others where the priority is to make money and the environmental objectives are less important. The natural and renewable building sector is going through a tough time, due to economic recession and also they need to develop successful business models that do not undermine the environmental quality of their products. It is also hard to distinguish what they have to offer from many other ‘greenwash’ and flawed solutions to making buildings more energy efficient.

Another problem results from confusion over the word ‘renewable’. Renewable materials have nothing to do with renewable energy. Generating renewable energy is not always a sustainable practice. Clearly alternatives to fossil fuel, coal, oil and nuclear energy are needed, but the manufacturing of photovoltaic cells that pollutes local watercourses and uses dangerous materials is part of a technology that uses manmade, not renewable materials:

A solar panel factory in eastern China has been shut down after protests by local residents over pollution fears. Some 500 villagers staged a three-day protest following the death of large numbers of fish in a local river. Some demonstrators broke into the plant in Zhejiang province, destroying offices and overturning company cars before being dispersed by riot police. Tests on water samples showed high levels of fluoride, which can be toxic in high doses, officials said.

(BBC News 2011)

Confusion is caused by mainstream businesses who claim almost every construction material and method is ‘green’ They pay for environmental assessment methods, certificates and standards that are diluted to the point where they become meaningless. When everything seems to be greenwash, it is easy to lose sight of those solutions that do work, and thus natural renewable building materials can be tainted by consumer cynicism about bogus claims. When some of the new energy efficiency technologies don’t work, as well as they should, instead of identifying the flaws in the technologies, they blame the people in the buildings for being too stupid not to live in an environmentally friendly way! People don’t understand how to live in an energy efficient house, they argue. A government-sponsored conference even discussed what was termed ‘misuse of buildings’ (ESRC 2009). It is clear that every householder will have to embrace the need to save energy and reduce CO2 emissions, but solutions and technologies used to achieve this must be easy, simple to understand and user-friendly and safe.

There is no doubt that there is a need to change attitudes, but not just the attitudes of ordinary building occupants. It is changing the attitudes of the professionals, scientists, academics and envirocrats that is the real challenge. They have to be persuaded not to go running after the latest high-tech ‘snake oil’ solutions, but to carefully consider the environmental impact of what they do in a holistic way. Proposals should be ethical, responsible and based on good science. Only then will we begin to see genuinely sustainable ways forward. One of the reasons this doesn’t happen is due to the way in which research is now funded and directed, much of it linked to industrial vested interests.

Government research funding in many advanced countries now expects a quick business return on their investment and this excludes research that is more thoughtful and critical. If you cannot find industrial sponsors and immediate users it is almost impossible to develop innovative solutions.

The intrinsic value of intellectual enquiry and exploratory research is not a concept easily sold to the Treasury (nor, rather more worryingly to UK research councils). … University research must demonstrate strong potential for short term (socio)-economic impact for it to be considered worthy of funding.

(Moriarty, 2011)

As a result, there is a lack of good quality independent research into sustainable housing and, in particular, building physics and materials science. The need for better building physics and science is discussed at some length with a critical account of current approaches.

I believe that RHP was poorly conceived and was an example of poorly thought through government policy and action. Civil servants seem to assume that if industry and housing developers are given a handout of a few million pounds, to be spent in a few months, something – anything – will come out of it. The lack of care in defining objectives, criteria and outcomes and the failure to allocate money with openness and fairness, followed by careful independent monitoring, is very disappointing and is dissected in Chapter 3.

However, a lot of useful experience and information has and will come from the RHP, despite its many flaws, and hopefully this book will have ensured that the appropriate lessons can be learned.

Chapter overview

In Chapter 1 the nature of renewable materials is explored in greater depth. Where do they come from, what are they made of and how do they get into the construction supply chain? The difference is explored between artisan and self-build materials such as earth and straw, and more highly processed and manufactured products such as wood fibre insulation boards. The difference between natural and synthetic materials also has to be understood and the environmental drawbacks of normal building methods are considered.

Chapter 2 gives more detail of the RHP with an account of each of the 12 case study projects.

Chapter 3 is an account of the RHP itself with details of how it came about and how it was funded and managed by government agencies.

Chapter 4 provides an analysis of the issues that emerged from the 12 case studies.

In Chapter 5 the policy context of energy and sustainability policy is examined in the UK, Europe and internationally, to see how this affects the use of natural and renewable materials in the market for insulation and other construction materials. The difference between energy in use and embodied energy is discussed, as this is central to the reason why even many environmentally progressive people ignore or are even hostile to the case for natural and renewable materials. The weaknesses of mainstream modern methods of construction and conventional proposals for the future development of housing and building are considered.

Chapter 6 is a discussion of building physics and science. Energy performance, moisture, durability, health and similar issues are considered. A critical evaluation of assessment, accreditation and labelling of materials and green buildings is central to this, and a review of some of the research in the field is provided.

Chapter 7 outlines other examples of projects outside the RHP, using (or in some cases not using) a range of alternative innovative approaches.

Chapter 8 examines the case for natural and renewable materials and looks at the prospects for them in the future.

References

BBC News Asia Pacific www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-pacific-14968605 (viewed 19 September 2011)

Bevan R. and Woolley T. Hemp Lime Construction BRE Press 2008

Dale S. and Saville J. ‘The Compatibility of Building regulations with Projects under new Low Impact Development Policies’ (unpublished paper) 2012

ESRC seminar series mapping the public policy landscape how people use and ‘misuse’ buildings, 26 January 2009 http://www.esrc.ac.uk/funding-and-guidance/collaboration/seminars/archive/buildings.aspx

Lammas Project http://www.lammas.org.uk/ (viewed 15.3.12)

Moriarty P. (2011) Scientists for Global Responsibility (SGR) Newsletter Issue 40 autumn 2011. p.15

Olsen R. Handmade Houses: A Free-Spirited Century of Earth-Friendly Home Design, Rizzoli 2012

Watkins T. The Human House, Sustainable Design. Karaka Bay Press, Auckland 2009

Woolley T. Natural Building Crowood Press 2006

1. Renewable and non-renewable materials

…many of us feel motivated to choose environmentally friendly products, even if they cost a little bit more. We know that products can be made from rare natural resources or from renewable raw materials, with or without unfair labour, with chemical input or from organic agriculture, with more or less energy based emissions. This is not a question of income but one of willingness.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!