20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: J A Allen

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

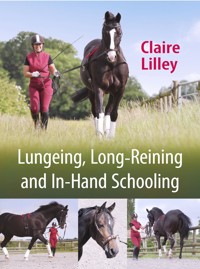

Schooling the horse is not just about riding - many problems or misunderstandings between horse and rider can, and should be, sorted out on the ground before attempting to ride at all. This book explains how to school your horse from the ground, starting with fundamental techniques, and gives progressive exercises to work through. It explains the importance of stretching work, how to establish a correct outline, and how to build strength and suppleness. Remedial work is also included to improve crookedness, unbalance, and stiffness, for example. Also covered is the use of training aids where necessary, and schooling over ground poles and cavaletti, as well as jumping the horse on the lunge. Observing your horse working without a rider gives you valuable insight as to the correctness of his paces, how his muscle development can be improved, and his general attitude and willingness. When your horse is moving beautifully on his own, there is no reason why he cannot do the same with you in the saddle.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 190

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

Lungeing, Long-Reining

and In-Hand Schooling

CLAIRE LILLEY

J.A. ALLEN

First published in 2015 by J.A. Allen, an imprint of The Crowood Press Ltd, Ramsbury, Marlborough, Wiltshire, SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book edition first published in 2017

© Claire Lilley 2015

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

ISBN 978 0 908809 69 8

The right of Claire Lilley to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Disclaimer of Liability

The author and publisher shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in this book. While the book is as accurate as the author can make it, there may be errors, omissions, and inaccuracies.

Edited by Martin Diggle

Photographs Dougald Ballardie

Line drawings by Carole Vincer

Dedication

This book is dedicated to ‘The Boys’ and Amadeus – a very special horse who is never forgotten.

Contents

Acknowledgements

The Horses

Introduction

A brief history of groundwork

The importance of groundwork today

1. Equipment

For the horse

For the handler

2. The Unbacked Horse

Basic handling – manners and obedience

In the school

In the field

Building a relationship

3. Groundwork Training for the Rider/Handler

In-hand work

Lungeing

Long-reining

4. In-hand Work

Basic in-hand work

More advanced in-hand work

In-hand exercises to try

Common in-hand problems and solutions

5. Lungeing

Stretching work

Establishing a correct outline with side-reins

Working in walk, trot and canter

Free-schooling

Lungeing exercises to try

Common lungeing problems and solutions

Remedial work

6. Long-reining

Long-reining on a circle (double-lungeing)

Double-lungeing exercises to try

Common double-lungeing problems and solutions

Remedial work

Long-reining on straight lines

Long-reining exercises to try

Common long-reining problems and solutions

7. Ground Poles and Cavalletti

Ground poles

Cavalletti

Pole and cavalletti exercises to try

Problem-solving and remedial work

8. Jumping

Introducing jumping in hand

Common jumping problems and solutions

9. Lungeing the Rider

Suitability of the horse

The instructor

Equipment and preparation

The rider’s perspective

Conclusion

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Lesley Gowers of J. A. Allen for giving me the opportunity to write this book. I have had it in mind for several years, and am thrilled that it has finally come to fruition. Thank you to Martin Diggle for being on my wavelength throughout the editing process, and to Carole Vincer for turning my rough drawings into the clear diagrams to illustrate the exercises. My husband has, as always, been brilliant at taking photographs with meaning. It is so difficult to capture the exact moment to go with what I am attempting to say, but I hope you will understand what I am trying to put across throughout this book. I am also very grateful to my friend Lorraine Mahoney for allowing me to use her and her horse Merlin for some of the photos.

And finally, a big thank-you to ‘The Boys’ – Heinrich, Norman and Mr Foley who teach me something new every day, and bring me to ever-increasing levels of self-awareness, which is an essential part of training horses.

The Horses

THE HORSES WHO appear most frequently in the photos used to illustrate this book are three of my own: Mr Foley (a 3-year-old Dutch x Thoroughbred gelding, real name Spartan Revelation), Heinrich (a 15-year-old Trakehner gelding, real name Broomdowns Donaupasquale) and Norman (a 12-yearold Hanoverian x Thoroughbred gelding, real name Dangerous Liaison). Amadeus, who also makes an appearance, was my Lippizaner x Thoroughbred gelding, who was about 10 years old at the time of the photos. I bought Amadeus as a yearling having seen him parading around a field at the head of a herd of young warmbloods. Norman is the only one I have not started from very young – he came to me as a 7-year-old from a showing background and has undergone a huge transformation over the last couple of years. I have known Heinrich and Mr Foley from a few days old; they were both bred by my friend Lynne Balcombe of Broomdown Stud in Kent.

Introduction

THERE ARE MANY misconceptions about lungeing. It is not about trotting the horse endlessly around in small circles ‘to take the edge off him’ before getting on board. Nor is it about strapping him into ‘an outline’ with his chin on his chest until he ‘gives in’.

The horse likes to move: movement is natural to him. Whether schooling the horse from the ground or from the saddle, training is about learning how to work in harmony with the horse, developing his mind and body to make him more beautiful and powerful.

Your horse should trust that you would not frighten or hurt him. You need to have faith that he will not forget you exist and mow you down if he gets spooked. It is your duty as a horse owner to care for the horse, and to look after his needs, taking into consideration his natural instincts of being a flight animal. He needs to be part of your ‘herd’ with you as ‘herd leader’. This entails training the horse to understand his role. A happy horse is one who understands where he fits in, that he is cared for, fed and watered, and that he is appreciated and loved by you.

‘Working from the ground’ encompasses everything from developing trust and responsiveness to developing the right muscles needed for ridden work, and teaching the horse an understanding of the rein and whip aids. In fact, many ridden problems can be rectified from the ground. Riders so often battle on with their horses, their idea of a solution being to purchase a new saddle, a stronger bit, or treatment by this or that therapist, rather than spending time schooling their horse from the ground. Lungeing, in-hand work, and long-reining are invaluable when trying to get to the bottom of a ridden issue. Being on the ground allows the rider to observe how their horse behaves and moves without them. More often than not, groundwork is a wake-up call for the rider. If the horse can, for instance, canter perfectly happily on the left rein without the rider, but has issues when ridden, this should give the rider a huge clue that the problem is more likely to be theirs rather than the horse’s!

The horse is a flight animal by nature but, as well as running away from danger, will run free from sheer pleasure.

A good relationship with your horse is built on trust and confidence in each other. If you trust your horse, he will trust you. If you have confidence in his ability, he will have confidence in you as a rider and trainer.

As I hinted at the start of this introduction, lungeing, to many people, is about the horse going round and around in circles at a fast trot to ‘get him going forwards’. I have also heard the following remarks so many times: ‘Lungeing is boring.’ ‘My horse hates lungeing.’ ‘My horse refuses to lunge.’ Have these people asked themselves why their horses hate lungeing, or refuse to lunge. Why do riders think lungeing is boring? Is it because they do not have the patience to spend many months painstakingly working with their horse?

Regarding impatience and possibly looking for a ‘quick fix’, I should state unequivocally that ‘quick fixes’ don’t work in equestrian training and some attempted methods are morally wrong. For example, strapping a horse into a ‘shape’ and leaving him in his stable for hours on end is simply cruel and counterproductive and similar practices such as riding or lungeing him with his chin on his chest, so he struggles to breathe or see where he is going (‘rollkur’), are inhumane. Abusing him with a whip, using a sharp bit that cuts his mouth, or spikes on his legs to make him pick his feet up, are all barbaric.

Battling with your horse is unnecessary and can be avoided by sorting out issues on the ground, and going back to basics.

Seriously overbending the horse (‘rollkur’) does not help him to work though his back, or the hind legs to engage. It inhibits his breathing and vision and causes him to go into the state of ‘helplessness’ where he mentally blocks out discomfort. This is often misinterpreted as ‘submission’.

A pleasing picture of horse and rider in harmony, with the horse relaxing on a long rein.

Schooling from the ground is gymnastic work for the horse, and it is important that he develops the correct muscles, can stretch fully forwards and downwards, and work in a correctly rounded outline into a steady contact as a preparation for ridden work.

Since this is not a book about gadgetry, I have not gone into details about everything you could possibly use to lunge a horse in. I have stuck to classical principles, with simple ‘old-fashioned’ items of equipment that have been tried and tested over time. I was taught to lunge in a simple, no-nonsense sort of way, which has stood me in good stead over many years. I have trained many, many horses this way with great success, so, although I have tried other ways just to test them out for myself (being of the mind that you should not talk about or criticize things you do not understand), every time I have come back to the old ways, which have worked for me, and I hope they will make sense and be effective for you with your own horse. A lot of what I do I have discovered by working with many different horses. It is the horses that let you know what is right and what is wrong, as long as you are perceptive enough to read the signs! This book is very much about doing just that – reading the horse, his reactions to you, keeping an eye on his muscular development, building his trust and confidence in you as his ‘person’.

Lungeing the horse in plain and simple, correctly fitted side-reins to develop the right muscles by working in a rounded outline.

Long-reining on a circle, or ‘double-lungeing’, teaches both horse and handler about the importance of ‘working into a steady contact’.

A brief history of groundwork

Mankind’s first use of horses was as a food source, then as a pack and harness animal. By around 900 BC, it is known that the Assyrians had mounted troops, and they were followed by various other races, including the Greeks. With military prowess such an important aspect of the Ancient World, it is no surprise that the pre-Christian era saw major developments in the use of tack, in mounted horsemanship and horse management. In this respect, working the horse from the ground is a practice that is known to date back at least to the time of the Greek military commander and philosopher, Xenophon (c. 430–354 BC). Xenophon’s writings are testament to an amazing knowledge of horses, and contain much that is still relevant today. Old carvings and pictures from this period show men beside their horses, training from the ground as well as riding them. However, the decline of the Ancient Greek civilization saw a parallel decline in these skills, which were not really revived until the time of the European Renaissance.

The Renaissance from an equestrian perspective began in Italy, with Federico Grisone (whose ideas were based on the work of Xenophon), and the founding of the Neapolitan School. One of Grisone’s books, Gil Ordini di Cavalare (1555) was the first book on riding to be published in Italy, and was subsequently translated into French and German. Grisone’s contemporary, Cesar Fiaschi, developed Grisone’s ideas and was the teacher of Giambattista Pignatelli, widely regarded as the most influential figure of the Neapolitan School. Some of Pignatelli’s pupils were to become key figures in the development of equitation in their own countries, including France, Germany, Austria, Spain, Denmark and England.

In time, various schools of what became classical equitation were founded. The most famous of these (and still in existence) is the Spanish Riding School (1572), but another from a similar era was the Parisian Academy founded by Antoine de Pluvinel (1555–1620), a former pupil of Pignatelli’s. A century or so later, Paris was also the location of the Academy of François Robichon de la Guérinière, a trainer whose ideas continue to permeate classical thinking to the present day. During this developmental period, most English riders were primarily interested in hunting and racing, and had little time for this ‘interior’ riding, the one exception being William Cavendish, Duke of Newcastle (1592–1676), whose book A General System of Horsemanship is referred to in the later writing of de la Guérinière.

As the classical schools (some of which were financed by the monarchy and aristocracy) gained ascendancy, they put on grand displays (known as ‘carousels’) to show off their equestrian prowess. Horses were trained in hand, working on piaffe and passage, and in the ‘airs above the ground’ such as the courbette, ballotade and capriole, and on long-reins for passage, and the lateral movements of shoulder-in, travers, renvers and half-pass.

During this period, the equipment used for the in-hand work was developed. Lunge cavessons in various forms, with nosebands made from leather or metal, were used to teach the horse to be submissive. The nose aids with the lunge rein attached to the cavesson could be stronger than those using the bit reins, to protect the sensitive mouth. Rollers may have been used for long-reining horses in preparation for draught work before they were taken up for groundwork in the dressage sphere, and it is likely that they were an adaptation of the ‘saddle’ or ‘pad’ used in draught work. Various auxiliary reins were also invented, one of which, the Chambon (named for its French inventor) is referred to within these pages, being a valuable schooling aid.

Horses also used to be attached to two pillars to train them for working ‘on the spot’ in the piaffe but, on my last visit to The Spanish Riding School, this was no longer part of the show programme. However, public performances of both ridden and in-hand work by The Spanish Riding School, and others that follow the classical tradition, such as The Cadre Noir in France, the Royal Andalusian School of Equestrian Art and The Portuguese School of Equestrian Art can be seen to this day, and are well worth a visit.

The importance of groundwork today

Lungeing, long-reining and in-hand work remain very relevant to today’s equestrian sports.

In dressage, is it not better to educate the horse, and the rider, on the ground initially? A novice horse with sound basic training on the lunge to will be easier to ride and have every chance of progressing to the higher levels than one who has no muscular strength and poor concentration.

Dressage is the foundation training for all other equestrian sports; it is about the skill of using the seat, leg and rein aids (using a bit) as a whole as well as developing a true partnership with the horse. Issues that arise when riding, which often result in the rider using a stronger bit, a different noseband, giving different feed and so on, can so often be avoided by intelligent training from the ground.

Dressage is the foundation for all equestrian sports. A novice horse with sound basic training on the lunge to will be easier to ride and have every chance of progressing to the higher levels.

It takes may years of patient training, both from the ground as well as in the saddle, to achieve success at grand prix level in dressage.

Harmony between horses and their riders. If the horse has confidence in his rider from the ground, he will happily cope with all situations. These Andalusians are all aware of each other – note their ears are alert to their teammates, but they are also obedient to their riders.

Jumping on the lunge in the school, or tackling obstacles in the field or on the cross-country course, can be extremely useful for building the horse’s confidence. The horse’s speed and line of approach can be controlled from the ground. The person lungeing can assess the horse’s natural jumping ability, and can improve his athleticism and technique and teach the horse to think for himself, which can be a life-saver under saddle where the horse can save the situation and get the rider out of trouble.

In addition to benefiting what are often, nowadays, considered the main equestrian sports of dressage, showjumping and eventing, groundwork remains of great value in other areas. Lungeing and long-reining are part and parcel of preparing a horse to pull a vehicle. Driving horses have to be able to react instantly to their driver’s aids. The risk of a nasty accident can be prevented by spending time on responsiveness and clarity of the aids.

Competing at the highest level in showjumping. Horse and rider have total confidence in each other.

Eventing requires a real partnership between horse and rider to reach top level. This is not achieved by riding alone – all aspects of the horse’s care and training, including groundwork, play a very important part in being the very best.

The sport of vaulting requires a very special horse – one who can maintain a faultless rhythm on the lunge and be happy to work on the left rein (the rein normally used for this discipline) for prolonged periods. However, it goes without saying that horses used for vaulting must be schooled on both reins to keep them fit and supple and to prevent crookedness. They must also be totally unfazed by the gymnastics taking place on their backs, so developing calmness is a major part of the groundwork process.

An example of great control – driving horses warming up, working on long-reins in close proximity.

Carriage driving a four-in-hand in the dressage phase of a competition.

A team of four horses tackle the marathon course – a feat of great skill, requiring quick reactions from both driver and horses, and a huge amount of trust.

In showing classes, unless your horse or pony can stand impeccably still for the judge, you will undoubtedly lose marks, and obedience in hand is essential during the trot-up.

It is also the case that different aspects of groundwork can benefit each other. For example, lungeing a horse can be done in a school, a round pen, field – anywhere that has a safe, level surface. Confining lunge work to a designated small area or a round pen limits the possibilities of variation. The high fence of a pen may be useful if working the horse ‘free’, of if the horse has issues and is likely to jump out, but most people do not have such an enclosed area and, in any case, repeating the same-sized circle over and over again is bound to cause muscle strain and boredom. For this reason, I personally prefer to lunge in a conventional rectangular school, which gives me the option of working the horse in different patterns – on straight lines as well as different-sized circles, so training can be imaginative and varied, giving the horse a good gymnastic workout. However, if a horse is acting up and continually ‘gets away’ in such a situation, then in-hand work and/or long-reining can be useful to correct the problems before attempting to lunge again.

The vaulting horse must be extremely calm on the lunge, able to maintain a steady rhythm at canter, and totally unfazed by what is happening on his back at all times.

Standing still for inspection at a show. It is so important to teach your horse to remain calm in halt for a long time.

Leading in hand at a showing class.

Working the horse on long-reins in the field adds variety to schooling.

CHAPTER ONE

Equipment

IN THIS CHAPTER, I will look at the various items necessary for the different types of groundwork.

For the horse

Roller or saddle and girth

A roller or saddle is needed if you are working your horse in a piece of equipment that needs attaching to a girth.

A roller is ideal, as you can see the horse’s back muscles working (or not!) as he moves. A choice of roller rings at different heights is an advantage so that side-reins etc. can be attached at exactly the correct height for the individual horse. A roller pad will make for a cosy fit behind the withers, especially if your roller is not padded either side of the withers, which raises the roller slightly off the spine.

Lungeing in a saddle is fine if you are working from the ground as a preparation for riding. If you are using a saddle, it must fit well enough so that it does not slip forwards, or off to one side when the horse is moving. The girth must be secure enough to keep the saddle in place, especially if your horse is likely to play around. However, for the sensitive horse, or ticklish types, or youngsters being introduced to the girth for the first time, comfort is paramount. A soft, padded, or elasticated girth is useful here: don’t use the tough old leather girth that you found mouldering away in the corner of the tack room, because it will be stiff, and will rub the sensitive skin behind the elbows. Also, although the girth must be tight enough to do its job, it is important not to over-tighten it. If you do this, and/or do it up too suddenly, you can frighten your horse, and end up with a ‘girth-shy’ horse who will put his ears back as soon as he sees you approaching with his tack.

A lunge roller with rings at different heights is ideal for attaching side-reins to suit the individual horse. A roller pad will make for a cosy fit behind the withers, especially if your roller is not padded either side of the withers, which raises the roller slightly off the spine.