8,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

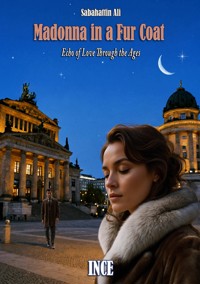

"Madonna in a Fur Coat" is a renowned novel that was first published in 1943, captivating readers with its poignant exploration of love in all its forms. Since its initial publication, it has continued to resonate with audiences worldwide, moving and enthralling countless readers across generations. Through its narrative, the novel delves into the complexities of love – from the unrequited yearnings to the elusive desires – showcasing how love, despite its beauty, can also be tinged with pain and longing. In this timeless tale, Sabahattin Ali masterfully illustrates that love, while often fraught with challenges and uncertainties, remains the most profound and rewarding of human emotions. The characters within the story are imbued with depth and complexity, their emotions laid bare against the backdrop of a changing world. As the narrative unfolds, readers are drawn into a rich tapestry of emotions, where love serves as both a source of solace and turmoil. Now, with this new translation, Ali's seminal work receives a refined and updated rendition, ensuring its accessibility and relevance for modern readers. The prose, elegant and evocative, retains the lyrical beauty of the original while offering a fresh perspective on timeless themes. Through meticulous translation, the nuances of Ali's prose are preserved, allowing readers to immerse themselves in the vivid imagery and vivid characterizations like never before.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 283

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Sabahattin Ali

Madonna in a Fur Coat

Contents

Madonna in a Fur Coat

June 20, 1933

Copyright

"There is a hidden world within each human being, and sometimes, if we're silent and attentive enough, we can hear the whisper of this hidden world and perhaps find a fragment of ourselves within it."

Ince

Madonna in a Fur Coat

So far, one of the individuals I've encountered by chance has perhaps had the greatest influence on me. It has been months, but I cannot escape his influence. When I'm alone, I see Raif Efendi's pure face, slightly out of touch with the world, but when he meets a person, he smiles and I can see his eyes come to life.

In no way was he an extraordinary man. He was even quite ordinary, devoid of any special characteristics, the likes of which we see and pass by hundreds of every day without noticing. In the aspects of his life that we know, and those we do not, there was certainly nothing that would pique curiosity. Often, when we see such people, we ask ourselves: "Why do they live? What do they find in life? What logic, what wisdom demands that they walk upon the earth and breathe?"

While pondering this, we only consider the exterior of these people; we do not think about the fact that they also have a head, and within it, whether they like it or not, a tirelessly working brain, and as a result of this, an inner world that is unique to them.

If we were to explore this unknown realm with basic human curiosity, instead of condemning them for their perceived lack of spiritual vitality or their inability to openly display their thoughts and emotions, we might discover things we never anticipated and find riches we never thought possible.

But for some reason, people tend to seek things that they believe they will find. It is certainly easier to find a hero who bravely descends a well where you know a dragon dwells than to find someone who ventures into a well without knowing what is hidden in the depths. It was purely by chance that I came to know Raif Efendi. After being dismissed from my modest clerical job at a bank - for reasons unknown to me, they simply said it was due to budget cuts, yet someone else was appointed in my position within a week - I searched for a long time for a job in Ankara.

With five or ten pennies, just enough, I managed to get through the summer months without working. The days of sleeping on my friends' sofas were over, as winter was approaching. I didn't even have enough money left to renew my expiring restaurant card for the next week. Even though I knew that many of the job interviews I had would not be successful, I was still disappointed when they indeed failed.

When I received rejections from the shops where I had applied, without my friends knowing, I roamed around late into the night, dejected. Even on the drinking evenings, when I was occasionally invited by acquaintances, I could not forget the hopelessness of my situation.

The odd thing was that as my difficulties increased and my needs made it impossible for me to stay afloat from one day to the next, my shyness and embarrassment also increased.

When I encountered acquaintances on the street who had helped me in my job search and had not treated me badly, I would lower my head and walk past them. Even towards friends, who I had previously asked for food without hesitation and from whom I had borrowed money without a second thought, I had changed. When asked, "How's your current situation?" I replied with an awkward smile, "Not bad... I find occasional temp jobs!" and I hurried away.

The more I relied on people, the more I felt the need to run away from them. One day, at dusk, I slowly walked down the deserted road between the station and the gallery house. I breathed in the wonderful Ankara autumn and tried to create a better mood in my soul.

The sun reflecting in the windows of the People's House and soaking the white marble building with blood-red spots, the smoke rising above the acacia and pine trees and it was unclear whether it was haze or dust, the workers returning from the construction site silently and slightly bent in their worn-out clothes, the asphalt with car tyre tracks... all seemed content with their existence.

Everything was accepted as it was.

There's nothing left for me to do either. Just at that moment, a car sped past me. As I turned my head to look, I thought I recognized the face behind the glass. Indeed, the car stopped after five to ten steps, the door opened; my schoolmate Hamdi, poked his head out and called me. I winced.

"Where are you going?" he asked.

"Nowhere, just taking a walk!"

"Come on, let's go to my place!"

Without waiting for my answer, he made space for me next to him. As he told me on the way, he had just been on a tour of several factories of the company he worked for:

"I've telegraphed home that I'm coming, they must be preparing. Otherwise, I wouldn't have dared to invite you!"

I laughed.

Since I had left the bank, I hadn't been in contact with Hamdi. I knew he was a deputy managing director of a company dealing with the brokerage of machinery etc., as well as forestry and timber industry, and that he was paid quite decently.

Therefore, I didn't approach him when I became unemployed, for fear that he would think I was coming to him to ask for a job or to help me out with money.

"Are you still at the bank?" he asked

I said, "No, I've left!"

He was surprised,

"Where are you now?"

I hesitated and then replied:

"I'm looking!"

He looked me up and down, considered my clothing, and likely didn't regret inviting me into his home, for he placed his hand on my shoulder with a friendly smile:

"We'll talk tonight and find a solution, don't worry!" He seemed content, confident, and now even had the luxury of helping acquaintances. I envied him. He lived in a small, but cosy house. He had a somewhat ugly but nice wife. Without hesitation, they kissed in my presence. Hamdi left me alone and went to wash up. As he had not introduced me to his wife, I stood in the middle of the living room, not knowing what to do.

His wife stood at the door, staring at me without showing it. She thought for a while. I think she wanted to say: Come in, sit down. But then, feeling it unnecessary, she slowly slipped out. I wondered why Hamdi, who was not negligent but very attentive, owing part of his success in life to this attention, had simply left me standing in the middle. I believe that one of the most crucial habits of men who have risen to important positions is this somewhat conscious obliviousness towards their old and lesser friends.

"Then, they suddenly adopt a humble and paternal demeanour, shifting from a formal mode of address to a casual one with their friends. They feel comfortable enough to interrupt the other's speech, to ask something randomly meaningless, and they do this quite naturally, often even with a smile full of pity and benevolence... I had experienced all of this so frequently in recent days that it never crossed my mind to feel angry or offended with Hamdi."

I thought I would simply stand up and leave without telling anyone, freeing myself from this uncomfortable situation. But at that moment, an old village woman in a white apron, headscarf, and patched black socks quietly brought the coffee. I sat down on one of the navy-blue chairs with the floral pattern and looked around. Family and artist photos hung on the walls, and on a bookshelf to the side, which apparently belonged to the Dame, there were a few novels and fashion magazines. Some photo albums lined up under a stool used as an ashtray stand looked as if they had been badly handled by guests. I didn't know what to do, so I picked one up, but before I could open it, Hamdi was standing in the door. With one hand, he was combing his wet hair, and with the other, he was buttoning up the buttons of his open white French shirt.

"So, how are you, tell me?" he asked.

"Nothing!... As I keep saying!"

He seemed pleased to have met me. Probably he was happy to show me the heights he had reached, or, thinking about my situation, he was glad he was not like me. For some reason, we feel relieved when we see people with whom we have spent some time facing misfortune or difficulties, as if we have avoided them ourselves. And we wish to extend sympathy and care towards these poor people, as if they had drawn upon themselves the difficulties that might strike us:

"Do you write or something?" he asked.

"Occasionally... poems, stories!"

"Does it pay?"

I laughed again.

He said:

"Forget these things, my dear," and he spoke of the successes of practical life and how harmful empty things like literature can be after school. He spoke as if giving advice to a small child, without caring for an answer or contradiction. And he did not shy away from showing through his behaviour that he drew this courage from his success in life.

I looked at him with admiration and smiled, which I thought was very foolish, because it encouraged him even more.

"Come to me early tomorrow," he said.

"Let's see if we can find a solution. I know you're not very industrious, but you're a smart boy. But that's alright. Life and necessities teach one a lot... Don't forget... Come to me early!"

While saying this, he seemed to have completely forgotten that he was one of the most famous slackers in the school. Perhaps, however, he was just speaking thoughtlessly, confident that I could not rub this in his face here. He made a motion as if to stand up, I immediately stood up and extended my hand:

"I apologise!", I said.

"Why, my dear, it's still early... But as you wish!"

I had forgotten that he had invited me for dinner, but he seemed not to have thought of it either. As I came to the door, I picked up my hat:

"Give my regards to the madam," I said.

"It will be alright, it will be alright, come by tomorrow, don't worry, my dear," he says, patting my shoulder.

As I left, it was already dark and the street lights were burning. I took a deep breath, and the air, although mixed with some dust, seemed wonderfully clean and refreshing.

I walked slowly.

The next day, around noon, I went to Hamdi's company. Actually, I didn't intend to when I left his house last night. There was also no clear commitment. He had bid me farewell with the usual words I always hear when I turn to a benefactor: "Let's see, we'll think of something!" Still, I went. Inside me, there was less hope than a desire to be humiliated for some reason. It was as if I wanted to say to my inner self: "Last night, you listened without a word and agreed that he is posing as your benefactor. Go on, follow through, you deserve it!" First, the caretaker led me into a small room and made me wait. When I entered Hamdi's office, I had the same foolish grin on my face as yesterday, and I was even more annoyed with myself. Hamdi was very busy, there was a pile of papers in front of him, and many officials were coming and going. He pointed me to a chair with his head and continued to focus on his work.

I sat down on the chair without daring to shake his hand. Now that I was sitting opposite him, I felt a real confusion, as if he really was my superior or even my benefactor, and I thought that my so humiliated self truly deserved this treatment. How great was the difference between my school friend and me, who had picked me up with his car on the street last night, in just over twelve hours!

How ridiculous, how foreign, how empty, and above all, how little it had to do with the true dignity of man, with the factors that determine the relationships between people.

Neither Hamdi nor I had really changed since last night; we were still who we were; but some things that he had learned about me and I about him, some of the small and trivial things, had led us in different directions...

The strange thing was that we both accepted this development as it was and took it for granted. My anger was not directed at Hamdi, not at myself, but simply at my presence here. As the room emptied, my friend raised his head and said:

"I've found work for you." Then he looked at me with his large, meaningful eyes and added:

"I've thought of a job for you that's not strenuous. You'll monitor our business with some banks, primarily our own bank. It's a kind of liaison officer between the company and the banks... In your free time, you sit inside and take care of your own things... Writing, poems, whatever you want... I've spoken to the manager; we'll take you on... But at the moment, we can't give you much: forty-five lira... Of course, it will be more in the future! So, come... Good luck."

He extended his hand, without standing up. I approached him and thanked him. On his face was a genuine satisfaction that he had done me a favour. I thought that he was not a bad person at all, that he was just fulfilling the requirements his position demanded of him, and that it might indeed be necessary.

But as I left the room, I lingered for a while in the hallway. I hesitated for a moment. Should I go into the room he had described to me, or should I leave this place? Then I slowly moved, my head facing forward, a few steps and asked the first caretaker I met for the room of the translator Raif Efendi. The man pointed to an unmarked door and walked past.

Again, I hesitated. Why couldn't I leave? Was it because I couldn't afford to pass up the forty lira monthly wage, or because I was afraid of embarrassing Hamdi? No! Months of job searching, not knowing where to go, where I would find work... And the hopelessness that now completely consumed me... That's what kept me in that dimly lit corridor until the other caretaker came by.

Eventually, I opened a random door and inside saw Raif Efendi, whom I did not know before. Yet, I immediately felt that the man I saw bent over his desk could be no one else. Then I wondered where this conviction came from.

Hamdi had said to me:

"I have had a desk reserved for you, our German translator, in Raif Efendi's room. He is a quiet, God-fearing man who harms no one."

At a time when everyone was addressed as Mr. and Mrs., he still referred to him as Efendi. Perhaps because the image that these descriptions created in my mind was very similar to that of the grey-haired man with glasses and a long beard that I had seen there, I went in without hesitation and asked the man, who looked at me with thoughtful eyes:

"You're Raif Efendi, aren't you?"

He looked at me for a while.

Then he said in a soft, almost fearful voice:

"Yes, it's me! You must be the official who's joining us. They set up your desk earlier. Please, be welcome!" he said.

I sat down on a chair and began to examine the faded ink stains and lines on the table. As is customary when sitting across from a stranger, I secretly wanted to scrutinise my room colleague, to give myself a first - and of course incorrect - impression of him with furtive glances.

But I saw that he felt no such desire, but rather bowed his head back down to the work before him and busied himself as if I were not in the room. This went on until lunchtime. Now, I turned my gaze freely towards the person in front of me. The parting of his closely cropped hair was starting to widen. There were many folds visible from beneath his small ears to his neck. He ran his long, thin fingers through the papers in front of him, translating with ease. Occasionally he looked up as if a word had come to mind that he couldn't find, and when our eyes met, his face contorted into a kind of smile.

Although he looked quite old from the side and from above, his face, especially when he laughed, had a naive and childlike expression that took you by surprise, and his trimmed, yellow moustache enhanced this expression even more. As I left for lunch, I saw that he, without moving from his spot, opened one of the drawers in the desk and pulled out a piece of bread wrapped in paper and a small lunchbox.

"Enjoy your meal," I said and left the room.

Although we sat facing each other in the same room for days, we barely spoke a word to each other. I got to know many officials from other departments and we even began to play backgammon together in the cafe in the evenings. From them, I learned that Raif Efendi was one of the longest-serving officials of the company. Before the founding of this company, he had worked as a translator for the bank where we were now employed, and nobody could remember when he had arrived there. It was said that he had a large family and could barely live on his salary. When I asked why the company, which was throwing money around, didn't raise his salary, the young officials laughed:

"Because he's a lazybones. It's doubtful whether he even speaks a proper language!"

However, I later found out that he spoke German perfectly. He could translate precisely and excellently. He could easily translate a letter concerning the specification of ash and fir wood to be shipped through the port of Sušak in Yugoslavia, or about the processing method and spare parts for sleeper drilling machines, and the specifications and contracts he translated from Turkish into German were sent without hesitation to the plant manager.

Each time he had a break, I saw him open the flap of his desk and read absently in a book without putting it down, and one day I asked him:

"What's that, Mr. Raif?"

As if I had caught him red-handed, he blushed and stammered:

"Nothing. A German novel!" and immediately closed the drawer.

Nevertheless, no one in the company believed that he could speak a foreign language. Perhaps they were right, for he did not look like someone who was proficient in a language. You never heard him utter a foreign word when he spoke, you never heard him mention that he was proficient in a language, you never saw foreign newspapers or magazines in his hands or pockets. In short, he was not one of those people who loudly and clearly say:

"I speak Franconian!"

The fact that he did not demand a pay raise due to his knowledge, nor look for other, better-paid positions, reinforced this opinion of him. He arrived promptly in the morning, ate lunch in his room, and immediately went home after making a small purchase in the evening. Although I offered numerous times, he was not willing to come to the café.

"They are waiting at home," he said.

I considered him a happy family man, wanting to be back with his children as quickly as possible. Later, it became clear to me that this was not at all the case, but that's a different story. Despite his persistence and diligence, he was treated poorly at the company. Whenever our Hamdi found a small typo in the translations of Raif Efendi, he would immediately call the poor man, and sometimes he came into our office and scolded him. It was easy to understand that my friend Hamdi, who was always a bit more cautious towards the other officials, was afraid of being treated badly by these young people, who all relied on some kind of favouritism.

He knew that Raif Efendi would never dare to fight back. He would blush and berate him through the whole department because of a translation that had been delayed by a few hours. What intoxicates people so much that they want to try their power and authority over their fellow men? Especially when the opportunity presents itself due to a sophisticated calculation only against certain individuals.

Raif Efendi sometimes fell ill and did not come to the company. Mostly, they were trivial colds. But a pleurisy, which he said he had had years ago, made him overly cautious. With a minor cold, he would immediately stay at home, put on several layers of wool underwear outside, never opened the window in the office, and never left the building without wrapping his neck and ears in scarves and pulling up the collar of his enduring, albeit somewhat worn, coat. Even during his illness, he did not neglect his work. The manuscripts to be translated were couriered to his home, and picked up a few hours later. Still, the manager and our Hamdi said to Raif Efendi:

"We won't throw you out, even if you are tearful and sickly!"

They did not hesitate to rub it in his face occasionally, and every time he returned after a few days of absence, they would ask him:

"How is it? Is it better now?"

They greeted him with sarcastic well-wishes for recovery. But I, too, found myself bored with Mr. Raif, and did not remain permanently in the company. With a briefcase in hand, I ran through the banks and offices from which we took orders, and occasionally sat down at my desk to prepare these documents and give an explanation to the director or the deputy director.

But I was convinced that this man, who sat so motionless across from me at his desk that I doubted he was alive, and this man, who was reading or translating a German novel, was in fact an insignificant and dull figure.

I thought that a person who has something in his soul cannot resist the urge to express it. I suspected that within such a silent and indifferent man there is a life that does not differ much from that of plants. He came here, did his work like a machine, read a few books with a verve I could not understand, and in the evening he did his shopping and went home. Likely, the illness was the only change in his life in these many days and even years that were exactly the same. As his friends reported, he had always lived this way. No one had ever seen him stirred in any way.

He always responded to the most inappropriate and unfair accusations of his superiors with the same calm and expressionless face, handed his translations to the typist, and thanked her upon receipt with the same meaningless smile.

One day, Hamdi came into our room because of a translation that had been delayed because the typists didn't listen to Raif Efendi, and said in a rather stern voice:

"How much longer are we supposed to wait? I've told you I'm in a hurry and need to go. You still haven't brought the translation of the Hungarian company's letter!" he exclaimed.

Raif Efendi sprang quickly from his chair and declared,

"I have it, sir! The ladies couldn't write it. They've been assigned other tasks!"

"Did I not say that this task was the most urgent of all?"

"Yes, sir, that's what I told them too!"

Hamdi yelled even louder,

"Instead of responding to me, do the task you were assigned!"

Then he slammed the door and left. Raif Efendi followed him out and went to the clerks to plead with them once more. I thought about Hamdi, who hadn't even deigned to cast a scornful look my way during this entire pointless scene. At this moment, the German translator, who had re-entered the room, sat down and lowered his head. On his face lay this unshakeable calm that can astonish and even anger you. He took a pencil and began to doodle on a piece of paper. It wasn't writing; it was the drawing of lines. But this movement wasn't the unconscious occupation of an angry man preoccupied with something else.

Rather, I saw a confident smile playing around the corners of his mouth, right below his yellow moustache. His hand moved slowly across the paper, and sometimes he would pause, squint his eyes and look ahead. From the faint smile on his face, I could tell that he was pleased with what he saw. Finally, he put the pencil down next to him and stared at the scribbled-on paper for a long time.

I watched him, not taking my eyes off him, and was surprised to see a completely new expression on his face: It was as if he was feeling pity for someone. Just as I was about to get up, he stood and returned to the room where the clerks were.

I jumped up, reached the opposite desk in one stride and picked up the sheet on which Raif Efendi had drawn something. As I examined it, I was frozen in astonishment. In five or ten simple but surprisingly skilled strokes, I saw Hamdi in all his glory. I don't think anyone else would have found the same resemblance, even if, taken individually, perhaps nothing was similar, but for a person who had just seen him screaming loudly in the middle of the room, it was impossible to mistake.

This mouth, opening in the shape of a rectangle, with animalistic fury and an indescribable meanness; these eyes shaped like slits, as though they were drowning in helplessness while trying to pierce the place they were looking at; this nose, whose wings widened in an exaggerated way towards the cheeks, giving the face an even wilder expression...

Yes, that was the image of Hamdi, or rather, his soul, standing there in front of me a few minutes ago. But this wasn't the main cause of my astonishment. Since my entry into the company, thus for months, I had made many contradictory judgments about Hamdi. Sometimes I tried to defend him, often I belittled him. I confused his true personality with the one that had brought him to his current position, and then I tried to separate them, only to find myself in a dead end.

Here was the Hamdi that Raif Efendi had revealed in a few strokes, the man I had long wanted to see but could not. Despite his primitive and wild facial expression, he also had a pitiful side. Nowhere else was the combination of cruelty and pity so obvious. It was as if I was truly getting to know my friend whom I'd known for ten years for the first time today. At the same time, this picture also explained Raif Efendi to me. Now I understood his unshakeable calm, his strange shyness when dealing with people. Could it be that a man who knew his surroundings so well, who could see so sharply and clearly into the heart of another, would get annoyed or angry at anyone?

What can such a man do when faced with a person squirming in all his pettiness in front of him, other than to remain motionless like a stone? All our regret, our defeats, our anger stem from the misunderstood and unexpected factors of the events we encounter. Is it possible to shake a man who is prepared for anything? Who knows what can come from whom?

Raif Efendi had again taken on a strange character for me. Despite the light that had just brightened on me about him, I felt that there were many contradictions. The accuracy of the lines of the picture that I held in my hand showed that it was not the work of an amateur.

The one who had made it must have been engaged in the art for many years. Here was not only an eye that really saw what it was seeing, but also a skill that was capable of recognising what it saw in all its subtleties. The door opened.

I wanted to quickly place my hand on the table, but I was too late. As if to apologise to Mr. Raif, who was approaching me with the translation of the letter from the Hungarian company:

"That's a very nice picture...", I said. I thought he would be surprised and afraid that I would reveal his secret. He took the sheet from me and smiled as always, oddly and thoughtfully:

"Many years ago, I dabbled in painting for a while," he said. "From time to time, out of habit, I doodle something... You see, these are insignificant things... Boring..."

He crumpled the picture in his palm and threw it into the wastebasket.

"The typist ladies have typed it up in a hurry!", he murmured.

"There are probably mistakes, but if I review it again, I will irritate Mr. Hamdi even more... He is right... I'd better take it and give it to him...".

He went out again.

I followed him with my eyes and whispered:

"He's right, he's right!"

From then on, everything Raif Efendi did interested me. Even his actions that were actually insignificant and irrelevant. I tried to seize every opportunity to talk to him and learn about his true identity. He seemed not to notice my excessive sociability. He continued to be polite to me, but always maintained a certain distance between us. No matter how much our friendship developed outwardly, inwardly he always remained closed off to me. My curiosity about him grew even more when I got to know his family and his position within it up close. Every step I took to get closer to him presented me with new puzzles. I visited him for the first time when he was ill. Hamdi wanted to send a manuscript by messenger to be translated by tomorrow:

"Give it to me so that I can pay him a visit," I said.

"Alright... Check on him. He's been away for too long this time!"

Indeed, his illness had lasted too long this time. He had not been in the company for a week. One of the caretakers described the house in the İsmetpaşa district. It was the middle of winter. Early in the morning, I set off on foot through the dark streets. I walked through narrow neighbourhoods with broken pavements that had nothing to do with the cobbled streets in Ankara. Hills and slopes lined up one after another. At the end of a long street, almost at the edge of town, I turned left and entered the café on the corner to ask about the house.

A two-storey, yellow-painted building stood alone amidst stony and sandy plots. I knew that Raif Efendi lived downstairs. I rang the doorbell and a girl about twelve years old opened the door. When I asked her about her father, she pulled a face and curled her lips:

"Come you in," she said.

The interior of the house was quite different from what I had imagined. In the hallway, which apparently served as a dining room, there was a large extendable table and a sideboard with crystal cutlery.

A beautiful Sivas rug lay on the floor, and the kitchen next door smelled of food. The girl first led me into the guest room.

The furniture here was also nice, even expensive. Red velvet armchairs, low walnut cigarette tables, and a huge radio on one side filled the room. All around, above the tables and on the backs of the sofas, hung finely embroidered cream lace and an "Amentü" sign in the shape of a ship.

A few minutes later the little girl brought coffee. For some reason, she always had this spoiled expression, wanting to look down on me, mock me. As she took the cup from my hand, she said:

"My father is ill, sir, he can't get up, come in!"

At the same time, it seemed to me with her eyes and eyebrows she wanted to say that I wasn't worthy of this treatment.

When I entered the room where Raif Efendi was sleeping, I was completely surprised. It was a small room, very different from the rest of the house, in which many white camp beds were lined up as if it were the dormitory of a school or a hospital. Raif Efendi lay in one of those beds, half sitting, under the white covers, trying to greet me behind his glasses. The two chairs in the room were covered with wool jackets, ladies' socks, and some discarded and thrown away silk dresses.

On one side of the room, clothes and stockings hung in an ordinary cherry-orange painted wardrobe, with a slightly open door, underneath which were knotted bundles. The room was in a state of chaotic disorder. On the bedside table next to Raif Efendi's bed, in a metal bowl, there was a dirty soup plate, apparently left over from the afternoon, a small jug with an open lid, and next to it a variety of medications in bottles and tubes.

"Sit down here, my dear," he said, pointing to the foot of the bed.

I sat down.

He wore a mottled ladies' wool cardigan. It was holed at the elbows and the back. His head rested on the white railings of the children's bed. His clothes hung over each other at the foot of the children's bed on my side.

When he noticed me looking around the room, he said:

"I sleep here with the children. They make quite a mess in the room... It's a small house anyway, we're quite cramped..." he said.

"Are there many of you?"

"I have an adult daughter who goes to the gymnasium. And the one you saw, my sister-in-law, her husband and my two brothers-in-law... We all live together. My sister-in-law also has children... Two children... You know the housing problems in Ankara. It's impossible to live separately..."

At that moment, there was a ring, and the noise and shouting indicated that a family member had come into the house.

At some point, the door of the room opened. A thick woman, about forty years old, with short cut hair falling over her ears and into her face, entered. She leaned in to Raif Efendi's ear and said something.

Without giving an answer, he pointed to me:

"One of my colleagues...", he introduced me. "My workmate."

Then he turned to his wife:

"Take it out of my jacket pocket!"

This time the woman said, without leaning into his ear:

"Oh, I didn't come for the money, who is supposed to get it? And you can't even get up!"

"Just send Nurten. The shop is only a few steps away!"

"How can I send a child, who is only a leg's length tall, to the supermarket at night? The girl in this cold... and will she even listen to me?"