11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

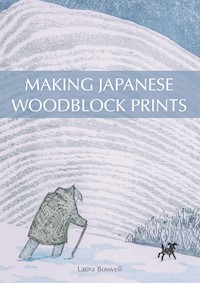

Japanese woodblock printing is a beautiful art that traces its roots back to the eighth century. It uses a unique system of registration, cutting and printing. This practical book explains the process from design drawing to finished print, and then introduces more advanced printing and carving techniques, plus advice on editioning your prints and their aftercare, tool care and sharpening. Supported by nearly 200 colour photographs, this new book advises on how to develop your ideas, turning them into sketches and a finished design drawing, then how to break an image into the various blocks needed to make a print. It also explains how to use a tracing paper transfer method to take your design from drawing to woodblock and, finally, explains the traditional systems of registration, cutting and printing that define an authentic Japanese woodblock.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

MAKING JAPANESE WOODBLOCK PRINTS

MAKING JAPANESE WOODBLOCK PRINTS

Laura Boswell

First published in 2019 by The Crowood Press Ltd Ramsbury, Marlborough Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2019

© Laura Boswell 2019

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 656 2

Photographs by Ben Boswell

This book is dedicated to the memory of Keiko Kadota

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

1DRAWING AND DESIGNING THE PRINT2TRANSFERRING THE DESIGN DRAWING ONTO THE WOOD3CUTTING THE KENTO TO CREATE REGISTRATION4CUTTING THE WOODBLOCK5PAPER PREPARATION6PREPARING FOR PRINTING AND TAKING PRACTICE PRINTS7SHADINGS AND OTHER PRINTING TECHNIQUES8EDITIONING AND FINAL PRINTING9ADDITIONAL CARVING TECHNIQUES AND TOOL SHARPENINGSUPPLIERS

GLOSSARY

INDEX

INTRODUCTION

The art of Japanese woodblock printing is growing in popularity among Western printmakers and rightly so; it is a flexible and non-toxic printing method that requires little space and no printing press. Materials and tools are becoming increasingly available and the medium is adaptable, allowing Western materials and tools to be substituted where Japanese versions are hard to find.

Japanese woodblock has a unique system of registration, cutting and printing. It often goes by the name mokuhanga (wood print). Woodblocks are carved with their registration cut into the wood alongside each block, while printing relies on brushes and water-based paints combined with rice paste, rather than inks and a roller. The built-in registration and brush printing makes for a thrifty approach, allowing the printmaker to fit multiple blocks on one sheet of wood. The multi-block process means the woodblocks are available to print as many times, and in as many ways, as the printmaker wishes.

Woodblock carver Will Francis carves a block of cherry ply.

How to Use This Book

This book is very much designed as a practical introduction to Japanese woodblock printing. It will take you through the process, step by step, from design drawing to finished print. Chapters 1 to 6 take you from drawing to basic printing, each chapter finishing with a list of goals that should have been achieved so that you can confirm that you are ready to progress. The later chapters detail more advanced printing and carving techniques plus advice on editioning your prints and their aftercare, tool care and sharpening.

The technique outlined on these pages is a contemporary and accessible approach, using a tracing paper transfer method to take your design from drawing to woodblock, rather than the traditional cutting of a key block and use of transfer prints outlined in this introduction. You will be using the traditional systems of registration, cutting and printing that define an authentic Japanese woodblock.

A Mindful Approach

It seems strange to advise on the correct mindset for a print process, but I cannot emphasize enough how much more smoothly your work will progress if you adopt a calm, patient and organized approach. Japanese woodblock is a method with no hard rules; rather it requires you to gain a feel for the balance of your materials and the movement of your tools, developing your skill and fluency through practice over time. If you can learn to relish working in a tidy, logical way with calm and focused attention, you will find the learning process itself rewarding, almost meditative, and you will avoid the simple mistakes that happen through rushing or working in a muddle.

Brief History of Japanese Woodblock

Origins

Woodblock printing arrived in Japan from China in the eighth century CE along with the art of papermaking. Japan’s climate and timber, combined with the potential that the Japanese saw in woodblock as a means of mass printing, elevated woodblock printing into a flourishing industry in its own right. Over time, woodblock printing became a sophisticated and respected art employing many artists, along with workshops of skilled carvers and printers, reaching its peak during the Edo period (1603–1868). Monochrome works, originally printed entirely in black sumi ink, became coloured, at first by hand and later with additional colour blocks. It was the need for a fast, accurate method for printing in colour that led to the development of the kento registration system that you will also learn to use.

By the mid-1700s, colour art prints were becoming increasingly rich and complex. There was a ready market in Japan’s wealthy merchant classes who, denied the more rarefied art forms of the aristocracy, embraced woodblock prints as their own. Woodblock prints from this time are known by the name of Ukiyo-e. This translates as ‘pictures of the floating world’ and has its origins in a Buddhist concept of a transitory and changeable sensual world. These are the prints that were to have a major influence on nineteenth-century Western artists, captivated by the woodblocks’ linear, flat appearance, exotic subject matter and asymmetric composition.

Print Production during the Edo Period

Woodblock was the sole means of mass printing during the Edo period in Japan and encompassed everything from artistic prints to sweet wrappers. It was a time of intense competition and demand for all kinds of woodblock printing with eshi (best defined as men doing the work of graphic designers and illustrators) working alongside the gaka (fine artists). Boundaries between eshi and gaka were not always clearly defined and some men fulfilled both roles. At this time woodblock printing was a combined effort, involving the work of a publisher, artist, carvers and printers. The publisher was in control of the process, sourcing clients, financing the work and owning copyright. He either found commissions for work that could be produced by eshi, or sought patrons for the particular talents of gaka such as Utagawa (Andou) Hiroshige or Katushika Hokusai.

Once the publisher had work, he commissioned the eshi or gaka to produce a detailed brush drawing onto thin paper called a hanshita. This was taken to the horishi, master carver, who would paste the drawing face down onto cherry wood and cut the ‘key block’ (sometimes known as the ‘line block’ since it reproduced all the outline details needed to define the coloured areas of the print). Details such as repeating prints on fabric or the individual hairs of hairlines were often left for the horishi to interpret and complete. Several monochrome copies, called kyogo, would be taken from the key block. These were returned to the artist who would add samples of the colours required, along with marking up the appropriate position for each colour. Once the colour samples were supplied, the artist’s involvement with the work was finished and the craftsmen took over. Marked-up kyogo were pasted to cherry wood as guides for carvers who cut the colour blocks to accompany the key block. Once the blocks were finished, the printers produced as many prints as the market demanded. Prints were often produced in great numbers and, with the exception of fine quality prints made specifically for collection, sold relatively cheaply. There was no concept of the artist printmaker, creating a limited edition print from start to finish, as there is today.

Shin-hanga (New Print)

This twentieth-century print movement is largely attributed to the publisher Shōzaburō Watanabe, though other publishers were involved. The movement still worked within the traditional roles of the Edo period with publisher and artist relying on the expertise of the carving and print workshops, but the resulting prints reflected a far greater freedom and diversity of expression than Ukiyo-e prints, with modern themes often reflecting the influence of Western art. Although the movement died out in the 1960s, there are still artists who work with master carvers and printers in this way. Mokuhankan, a carving and printing workshop based in Tokyo established and run by David Bull, is a good example of this practice. Bull collaborates with artists, notably Jed Henry, to produce modern prints that meet the exacting standards of traditional Edo period works.

Will Francis lifting a ‘kyogo’, a print made on gampi tissue, from his key block. This kyogo will be marked up for colour and then stuck face down on a fresh wood block to act as a guide for cutting the colour blocks.

A set of cherry blocks cut using traditional methods for the print A Frugal Hero (designed by Jed Henry and cut by Will Francis).

Sō saku-hanga (Creative Print)

The concept of the artist printmaker, creating the artwork, blocks and final prints, appeared in Japan in the early twentieth century, along with increasing interest in individual expression and concepts surrounding modernity. The artists who embraced the process often needed additional work to make a living, such as carving or illustration, and consequently there was something of an overlap between sōsaku-hanga and the shin-hanga movement.

The advent of World War Two brought difficulty and hardship for Japanese printmakers along with a scarcity of supplies. However, sōsaku-hanga and shin-hanga prints were to play a pivotal part in the post-war regeneration of Japan. The popularity of prints as souvenirs among the occupying American forces, along with the support and interest of influential American connoisseurs, created both a market in Japan and a place on the world stage for shin-hanga and sōsaku-hanga work. Sōsaku-hanga prints continued to grow in popularity and influence, winning prizes in the West, notably at the São Paulo Biennial in 1951, Japan’s first post-war participation in an international exhibition.

Star Worshipper 1, designed, cut and printed by Mara Cozzolino.

Towards the end of the twentieth century, interest had moved on in Japan, with printmakers embracing Western techniques and oil-based printmaking, while a few traditional workshops remained, producing copies of Ukiyo-e prints. Today, the outlook is much brighter, with a revival of respect for this adaptable technique along with an appreciation for the skills involved and for the remaining experts in the technique. Classes in Japanese woodblock printing are growing in number both in Japan and across the world.

CHAPTER ONE

DRAWING AND DESIGNING THE PRINT

Japanese woodblock printing is a ‘multi-block’ process. This simply means that to arrive at your finished print, you will be designing, cutting and printing a set of several blocks. These will fit together to complete your picture. This chapter deals with the process of developing your ideas, turning them into sketches and refining your sketches into a finished design drawing, ready for transfer onto your wood for cutting. It explains how to plan an appropriately simple image for a starter print, including understanding of how an image is broken into the various blocks needed to make a print, plus the various ways you can divide up your design to create blocks that print to best effect.

Developing a sketch for later use.

Inspiration

Historic Japanese woodblock prints have such a strong visual identity that it is tempting to think that the medium is best suited to a few traditional themes. However, if you dig a little deeper you will find Japanese woodblock prints depicting any number of subjects and ideas with a rich and varied approach. In a medium that is suited to everything from the most delicate observational studies to bold abstracts, there is no need to limit your ideas. Bear in mind that your personal tastes, interests and preferences will make for the most satisfying prints both to create and to view. In addition, by following your own ideas, your prints will develop a strong and individual identity.

Get into the habit of jotting down ideas and sketches, saving clippings or taking photos whenever and wherever you see possibilities for a print. Inspiration often comes from unexpected places and it could be a scrap of fabric or the photo you snapped from the bus that proves to be the start of a great print. Take a magpie approach to your collecting and scoop up anything that you find of interest.

Allow time for ideas to develop and don’t be too hasty to throw anything away, especially not your sketches. You should never be judgemental about the quality of your drawing when jotting down ideas; remember you are taking notes, not creating a masterpiece. Review your visual collection regularly and ask yourself why you chose to keep these particular visual cues and how they might work in a print. Always jot down any print ideas in notes or a thumbnail sketch as they arise. You may not be able to turn your inspiration into a print immediately, but you will have moved towards your goal by developing and recording your thoughts.

Always be on the lookout for inspiration and keep a visual record of your findings, jotting down ideas as they occur.

Elements of Design

Printmaking is very different from drawing and painting. It is process-led, meaning you must design, cut blocks and print to arrive at your desired image, rather than make an immediate impact with a brush or pencil. This means your Japanese woodblock prints will require a different and more graphic visual language, especially in the early days. While there are certainly plenty of traditional prints that could pass for watercolour paintings, it is worth remembering that they are the products of expert specialists with many years of experience. Better to be bold and simple in your ideas when learning your craft. Here are a few suggestions taken from the Japanese woodblock tradition for ways of making a simple design interesting.

•Scale: do not be afraid to make your main subject rather larger in a print than you might in a painting. This boldness will give your print strength and, on a practical note, your blocks will be easier to cut accurately and well. This may mean cropping your subject at the edges of the print, but this is often a positive step and makes for a much more visually exciting print.

•Composition: experiment with unexpected compositions. Try moving your horizon until it is very high or very low. Play with moving your main subject to the far edges of your print, or try obscuring part of it with something large in the foreground. These unexpected proportions and juxtapositions challenge the viewer and turn a simple print into something more sophisticated.

•Empty space: never be afraid to embrace areas of empty space in your print. This could be a simple block of colour, or even areas using the unprinted paper surface as part of the design. By having areas of detail balanced against areas of quiet space, your print will be visually interesting. Designing a print that carries the same level of visual detail and information from edge to edge with success is a tricky challenge.

•Simplify: catching every detail of your subject would make for an admirably skilled print, but not necessarily a successful one. Part of the beauty of Japanese woodblock printmaking is learning how to simplify objects and shapes to catch their essence. When you are simplifying, look at the overall shape of the subject and the negative space around it, rather than the details of the subject itself. If you get these two basics right, very little detail is needed for your audience to read and appreciate your print.

These three prints will appear as examples throughout this book and follow the elements of design detailed here. The print area is 15cm × 20cm with a 2cm margin area (6in × 8in with a ¾in margin). All examples are printed on Fabriano Academia HP 200gsm.

Where to Begin

Before you take your ideas and sketches and turn them into a design for your Japanese woodblock print, there are some practicalities to consider. If you make a few decisions before you start, it will help to make the whole process easier to control and follow.

Measurements

Throughout this book, when following the sequence of actions, please use either metric or imperial measurements consistently. Do not mix them as they do not convert exactly.

EQUIPMENT AND MATERIALS LIST

Detailed descriptions of tools and materials and how to choose and care for them are included in the chapters that explain their use. There is a list of suppliers at the end of the book.

Cutting

Chisel for cutting kentosHangi-to cutting knife (right- or left-handed) Tools for clearing wood: U gouges and chisels V tools for creative cuttingShina ply woodblocks (sometimes called Japanese or Asian ply) Non-slip mat or bench hook Waterproof wood glue

Printing

Baren for taking the print impression Brush for wetting paper (also for sizing paper) Cheap brushes for mixing paints Printing brushes Rice flour to make rice paste (nori) (or readymade nori can be used if preferred) Paints in tubes, watercolour or gouache Sumi ink

Chopsticks

Papers

Drawing paper Tracing paper Carbon paper Printing paper Proofing paper Blank newsprint Baking parchment Newspaper or blotting paper to make a damp pack

Sundries