20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

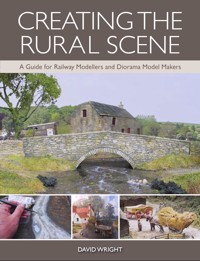

This invaluable, well-illustrated book is essential reading for all those who are interested in developing their modelling skills and creating realistic models of country houses, cottages and farm buildings for their railway layouts. The author encourages and inspires the reader and, moreover, emphasizes that railway modellers can achieve their objectives without purchasing expensive materials. Indeed, all the materials recommended in the book are either recycled or can be obtained quite cheaply.Topics covered include: The materials and equipment required to build models; Modelling methods and construction techniques; Painting, weathering and finishing; Creating a sympathetic setting for your models; Improving kits and 'off-the-shelf' models. The author presents in detail three different rural, scratch-built projects and , in a separate appendix, provides a colour reference guide, thus enabling the modeller to apply the correct colours and shades in order to create authentic and convincing-looking model buildings. An invaluable guide which provides all the information required to create convincing models of rural buildings. Aimed at all those interested in railway modelling whatever their level of ability, and those interested in modelling in general rather than in just railway modelling. Materials and equipment, modelling methods and construction techniques are covered. Superbly illustrated with 320 colour step-by-step photographs and diagrams. David Wright is a professional artist and model maker and provides hands-on experience at railway modelling workshops.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 209

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

Making Rural Buildings

FOR MODEL RAILWAYS

David Wright

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2013 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2013

© David Wright 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 560 7

DedicationI would like to dedicate this book to my good friend Dave Richards. Dave has always supported me, giving me encouragement with my model making. He is also credited with originating a good number of the photographic images in this book, for which I am very grateful.

Front cover image: A scene from the mill on the author’s layout Tawcombe. Photo: Steve Flint, courtesy of Railway Modeller magazine.

Frontispiece image by Dave Richards.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

CHAPTER 1: THE HISTORY OF RURAL BUILDINGS IN BRITAIN

CHAPTER 2: MAKING A START – RESEARCH, MEASUREMENTS, PHOTOGRAPHY AND WORKING DRAWINGS

CHAPTER 3: CONSTRUCTING A MODEL

CHAPTER 4: FINAL PAINTING, WEATHERING AND FINISHING

CHAPTER 5: SETTING YOUR MODEL BUILDING INTO THE LANDSC

CHAPTER 6: PROJECTS – SCRATCH-BUILDING THREE RURAL BUILDINGS

CHAPTER 7: IMPROVING KITS AND OFF-THE-SHELF MODELS

APPENDIX: COLOUR REFERENCE GUIDE

LIST OF SUPPLIERS

FURTHER INFORMATION

INDEX

PREFACE

From as long as I can remember, I have had an interest in making things. This interest has combined with an ability to observe things around me. From a very early age I would find myself recording what I saw, by making rough sketches. My father always encouraged me and indeed I must have inherited some of his artistic skills, as he was a talented artist himself. He also had a talent to design and make useful items for the home, which again must have rubbed off on my young mind. Like most young boys growing up in the fifties and sixties, I was bought a train set for a Christmas present. The first was a Hornby clockwork, set up on the living room floor. Then a few years later I was given a Tri-ang TT train set. This time my father and elder brother had fixed the layout down to a large baseboard with scenery. I remember it vividly as it gave me many hours of pleasure.

It was not long before I found myself wanting to add more buildings to the layout. My father saw my interest and bought me a card cottage kit. With his help, I made my first model building, thus setting the seeds of my future interest. From this beginning, many more buildings were to be constructed from the card Bilt-Ezee range. I remember making regular visits to the local model shop in Derby to select the next one to build. However, it would not be long before I started to design my own buildings using the card fold-up technique. My mother would save any cereal packaging for me to draw out and construct my first scratch-built efforts. At the same time as the visits to the model shop, my father would take me to see the wonderful O gauge ‘Kirtley’ Midland model railway exhibit, then housed in the Derby Museum. This model made a lasting impression on my young mind, always being impressed with the quality of the buildings and scenery this layout displayed. Little did I know then that forty years on, I would be constructing the buildings for the rebuilt version of ‘Kirtley’, now housed in the Silk Mill, Derby’s former Museum of Industry. Through my teenage years other interests were soon to take over, like girls, pop music, football and so on.

Aged six with my father at the 1962 Derby Locomotive Works Open Day. Railways, both full size and in miniature, were always a part of this young boy’s life.

Photo: Colin Wright

‘Washgate Barn’ was the first commissioned model building that I constructed for the Midland Railway exhibit housed in the Silk Mill, Derby. This layout is a rebuild of the original model of ‘Kirtley’, which had proved such an inspiration for me as a boy.

Photo: Jeff Mander

My artistic ability was to give me a career as a graphic designer and illustrator. From time to time the job would involve model making, such as creating models of exhibition stands for companies exhibiting their products and services at the National Exhibition Centre. My interest in model railways was rekindled after I was invited along by a work colleague to the local Model Railway Club. The interest from those early years was soon revived with the desire to create a layout and replicate the buildings of the selected area on which I based my model railway. My interest was extended with a visit to Pendon Museum in Oxfordshire. The quality of the model buildings and scenery, representing rural Britain in the 1920s and 1930s, is exceptional and I would strongly recommend a visit. The buildings on display certainly gave me the inspiration to improve my scratch buildings and it became my benchmark to achieve something like the standards seen at Pendon. I hope by reading this book, you too will be inspired to have a go at creating some of our rural buildings for your model railway and have the satisfaction of building something you can be proud of.

The hobby of model railways is probably stronger now than it has ever been. This is evident from the amount of exhibitions around the country and the thousands of people visiting them. It is also true that most of us strive to achieve higher standards in our models. The market has never been better, especially for off-the-shelf examples. The amount of detail that can now be reproduced on an out-of-the-box model is truly amazing. Anybody just starting out, or getting back into the hobby, will be spoilt for choice with all the locomotives, rolling stock and, of course, the buildings that are now available. The scratch-builder, however, has not been left out completely. There is also an increasing range of materials and accessories available to help give you plenty of scope to build a good model.

Model railways have always been a good platform for learning and trying out new skills. Indeed, the hobby includes carpentry for baseboard construction, electronics for wiring, engineering for locomotive building – the list goes on. For me, though, the most enjoyable part of the hobby is the artistic element, whereby perhaps we can allow ourselves to be a little more imaginative and not be too concerned about the constraints that other areas of the hobby might demand. The skills required to achieve a reasonable standard when creating a building are achievable for the beginner, so long as you are prepared to take your time and always observe the world around you. There is no reason at all why you should not be rewarded with convincing results.

The 7mm Midland Railway exhibit, housed in the Silk Mill, Derby’s Museum of Industry. The water tower and the nearest station buildings were all built by the author as commissions.

Photo: Jeff Mander

Reading this book, and following the techniques and suggestions I have given, you should achieve something towards that goal. Remember that the main object of any hobby is to learn new things and, most importantly, to have fun doing it. The aim of this book is to provide you with the information, ideas and inspiration to be more creative when modelling rural buildings and to achieve a final result you can be justly proud of.

The small Prairie Tank 4550 pulls away from Tawcombe Station, past the allotments. This is the author’s own 4mm layout depiction of the rural Devonshire landscape in the 1930s.

Photo: Steve Flint, courtesy of Railway Modeller magazine

CHAPTER ONE

THE HISTORY OF RURAL BUILDINGS IN BRITAIN

Before we start to look at how we are going to construct models of our rural buildings, we need first to consider the history behind them. It is important to have some knowledge of how buildings have developed over the years and how different materials have been used to construct them. This will prove to be a valuable benefit when you come to build miniature versions for your model railway.

THE RURAL SETTING

In this country we are blessed to have such a diverse range of rural buildings. The reason for this is down to geography and the geology of the land. Most of our rural buildings will have been constructed from the local materials, giving them the distinct style and character of that particular region. We can identify what part of the UK we are in just by looking at the buildings found there; for instance, if we see cottages constructed of a golden ochre limestone we know that we are in the Cotswolds.

If we go back in history we will find that the population of Britain depended on the countryside for its existence. Small settlements started to grow up around areas of forest that had been cleared to work the land. These early farmers built themselves primitive shelters, which they shared with their livestock. In some cases, these settlements would grow to form small hamlets that would become the basis for our rural villages.

Up until the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the majority of people lived and worked in the countryside, where the villages developed into open and closed examples. Open settlements grew either around industrial workings, or on common land. The closed settlements were under the tighter control of the Lord of the Manor and the haphazard building of homes was restricted to a more uniformed architectural style and layout. More substantial materials and building techniques started to be used. These dramatic changes came about with the introduction of the Enclosures Acts, the majority of which were passed between 1750 and 1860 and gradually eroded the rights of local people to cultivate or graze animals on what had been common land. The Lord of the Manor would have a large country house built, serving as a status symbol of his wealth and importance. The house would be built a fair distance away from the villages and would be surrounded by parkland. The farmhouse also started to make its appearance into the British landscape.

Our Iron Age ancestors worked the land and reared livestock. They built circular houses, seen here in a recreation of a Celtic Village at St Fagans National History Museum in Wales.

More changes took place with the introduction of transportation and the formation of the Turnpike Trusts between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries, which saw tolls collected for maintenance of roads. These roads would start to criss-cross the countryside, linking villages together. Before this, the only connections were rough drovers’ tracks, used by farmers to move livestock to and from market.

In the second half of the eighteenth century, canals started to appear, linking towns with the countryside. Canals then gave way to the railways, which made the biggest impression. Now materials could be transported quickly around the country and new materials could be used to build or make improvements to rural buildings.

BUILDING MATERIALS: WALLS

We can now look at the materials used to construct rural buildings, starting with the walls.

TIMBER

The dwellings of the early settlements used wood for a basic framework. Thin strips of wood from hazel or willow, known as wattle, were then added, which would then be plastered in a clay mix known as daub. Later, more substantial frames started to be used. Two naturally curved branches would be selected from an oak tree and cut. These would be positioned to curve up to meet each other. This became a standard technique known as a ‘cruck frame’. Examples of this type of frame can still be seen today.

Oak framing continued to be used, although the box frame method came to be preferred. The black and white half-timbered buildings we all love today were built in this way. This method of timbering has been revived over the last couple of centuries, although mainly for decoration rather than forming any structural importance.

The infill material used for the early timber-framed buildings was wattle and daub. This was a mixture of mud and clay bonded together with straw and animal hair. Examples using this main building material can be seen in Devon, Somerset and Dorset, and is locally known as cob.

This cottage, now rebuilt at St Fagans, has walls made from clay known locally as clom. The clay is mixed with straw and small stones, then laid in layers. A cruck frame supports the roof. The roof has a sub-base of wattle and gorse, which is then topped with straw thatch.

This photograph shows the construction of a cruck frame, discovered after demolition. It now is a feature in a wall located on St Mary’s Gate, Wirksworth, Derbyshire.

A single-storey ‘long house’ built around 1508. This type of once-common farmhouse was created using a timber frame. The walls were covered in wattle and daub and finished with a lime wash. The roof is supported by a series of oak cruck ‘A’ frames. The long house is divided with accommodation for animals at one end. This rebuilt sample can be found at St Fagans National History Museum.

The illustration (A) shows the construction of a cruck frame. The two curved oak frames are brought together at the apex. A cross beam of oak forms a letter ‘A’, giving the frame lateral strength. Illustration (B) shows the cruck frame exposed on the end of a cottage in Lacock, Wiltshire.

An early timber-framed farmhouse of 1678, with a hipped roof of thatch. This rebuilt sample is at St Fagans National History Museum.

This example of a grand half-timbered manor house is located at Somersal Herbert, near Ashbourne, south Derbyshire. It was built by John Fitzherbert in 1564.

Wakelyn Hall is an impressive manor house in Hilton, south Derbyshire. This half-timbered building has two wings using an ‘H’ footprint, which became a popular style for country houses in the early seventeenth century.

A farmhouse constructed using a box timber frame with lath and plaster panels. This building still retains much of its original features at Doveridge, south Derbyshire.

The end elevation of the 1480s Grammar School in Ledbury, Herefordshire. This is a good example of a timber box frame with wooden mullion window frames.

When brick became more popular, the daub infill for timber frames was replaced with this, although timber could also be used to clad frames. Shiplap weather boarding became a feature of buildings in the south-eastern counties of England, especially Suffolk, Essex, Sussex and Kent.

STONE

Stone was used as a building material from early in history, although not originally for the humble dwelling. Stone would be used for its strength and for defence. From Roman times, stone masonry was used to construct defensive walls, forts and villas. The Romans brought amazing building skills to this country and we can still marvel at them today. Centuries of conflict and invasion led to the building of our castles and fortified manor houses. Stokesay in Shropshire is probably the best example of a fortified manor house. It also features a combination of the half-timbered box frame supported on a base of reinforced stone. Another feature was the tall square stone structure known as a pele tower. These were common in Wales and Northumbria and along the Scottish borders, where attack from ‘reivers’, savage border raiders, was still a threat.

The ruin of Throwley Old Hall stands overlooking the Manifold Valley in north Staffordshire. This Tudor manor house was built in 1503 using local limestone and non-local sandstone. The structure was built with defensive features to the walls.

This illustration of Fenny Bentley Hall in Derbyshire shows the defensive tower of the original hall, with the Tudor gables added at a later date.

Built from local slate from North Wales, this was the home of a wealthy farmer. The building features unglazed timber mullion windows and two substantial chimneys. The farmhouse has been rebuilt at St Fagans National History Museum.

The ruin of the original gatehouse to Mackworth Castle in Derbyshire dates from 1500. Attached are later estate workers’ cottages. This makes for an interesting combination of styles.

Religious buildings started to appear, with stone being the preferred material. Churches, monasteries and abbeys graced our land. Gradually stone started to replace earlier materials for housing, farm buildings and country houses. Some of the stone would be recycled both from defensive structures and the monasteries after their dissolution from 1536 to 1541.

Local stone was quarried for most of our rural buildings; this was lightly dressed for parts of the building where strength mattered, like the corner quoins, lintels and sills. The rest was constructed using rubble as an infill and would be joined together with a lime mortar. In some cases, mortar would not be used at all, just being dry-stone built. The local stone used would give the distinct character to the buildings seen in our countryside, from hard gritstones and granites through to the softer limestones, slates and shales. All were used to construct the buildings that harmonize perfectly with our rural landscape. For new builds in many parts of the countryside and especially in the National Parks, local stone will still be used as a facing over a shell built from more modern materials, keeping the building traditions alive today.

Cilewent Farmhouse was originally built in 1470. This is the 1734 rebuild in the form of a long house. The local stone structure boasted a cow house with room for twelve cattle, a substantial hay loft, stables and a dairy all contained under the long slate-covered roof. It has been rebuilt at St Fagans National History Museum.

An unusual tall limestone-built outhouse in Wirksworth, Derbyshire. Its original use is not known, although it was probably used to store grain.

BRICK

Brick-making first came to this country with the Romans. Examples of early bricks and tiles can be seen in the walls at York and other Roman sites around the country.

Throwley Barn was built slightly later than Throwley Old Hall, but using the same limestone. It is a fine example of an early Tudor long barn.

This farmhouse at Scropton, south Derbyshire, has an oak box timber frame with an infill of brick noggin. The roof would originally have been of thatch, but has been replaced with a covering of Staffordshire blue tiles.

This photograph illustrates the very decorative estate houses found at Ilam in Staffordshire. They feature elaborate bargeboards with finials and fancy shaped tiles are used to cover the roofs. The same patterns have been repeated on the walls with the art of tile hanging. The stone walls and chimney stacks have decorative embellishments added, all to reflect the estate owner’s wealth and importance.

This photograph shows the decorative diaper work with diamond patterns on the upper floor and chequer patterns to the lower. It has been created using blue header bricks in the walls of this cottage in Sudbury. Diaper work is a prominent feature of all the estate properties of this south Derbyshire village.

A revival of brick-making started in the eastern counties of England during the later thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries. This was due to a lack of local building stone, aggravated by timber also now being in short supply. In the country as well as in the towns, brick kilns or clamps were constructed and by the Tudor period brick-making had become a common skill. Good quality brick was now a serious rival to stone, especially with its strong properties when bonded together. In the country, bricks were first made on site using turf-fired clamps and later in brick-built kilns. Not all bricks would be fired to the same standard. The overfired (darker) bricks would be used where they could not be seen as much.

Bricks that had burned to a dark purple or slate colour were often laid using headers to form diamond and chequer patterns. This decorative use of sub-standard bricks became known as diaper work and would be used in the country house down to the humble estate workers’ cottages.

Facing bricks are still the most common building material today. Modern bricks, however, are now mass-produced in giant oil-fired tunnel kilns and lack the rustic qualities of their handmade predecessors.

TILES

Handmade tiles, although used mainly as a roofing material, were also used to cover walls. They were originally found as a feature of buildings in the south-east of England and East Anglia. This protective and decorative finish was revived during the Arts and Crafts period of 1860–1910 and is still a contemporary style today. Handmade clay tiles sometimes shaped on the bottom edge would be hung off wooden laths, a process simply known as tile hanging. In parts of the country where slate was abundant, this would be used in the same way.

RENDER

Render was used as a finish rather than a structural building material. Its purpose was both as a protection and decoration. The early renders were no more than clays, straw and animal dung.

Later, lime plaster and cement would be used, applied onto a light framework of horizontal strips of wood known as laths. In certain parts of the country, this lime plasterwork would have raised or combed patterns put into it. Pargetting was a common decoration found mainly in Suffolk. Colour was added to the plaster mix to produce pastel shades of pink, ochre and dark reds. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries blues and greens were introduced.

A smooth version of plaster rendering became a popular finish about the same time. It was used either totally flat, or sometimes with a fine mortar line chased in just for decoration. This finish originated in Italy and was known as stucco. It lasted as a fashionable finish into the Arts and Crafts period. Again, the stucco would be painted pastel colours or whitewashed. Another finish used was pebble dash, a rough aggregate of pebbles mixed with cement to give a much tougher result. Paint or whitewash was added to create the final effect.

The elaborate diaper patterns form the decorative facings to the walls of Sudbury Hall, south Derbyshire.

A substantial two-storey farmhouse built in 1610. The red colour to the rendered lime-washed walls was created by adding berries as a dye. It is thought that the reason for the bright colouring was to protect the house against evil spirits. The farmhouse has a typical long-straw thatch, with an extension in the form of a barn for livestock. It has been rebuilt at St Fagans National History Museum.

BUILDING MATERIALS: ROOFING

We will now turn our attention to the roofs of buildings.

THATCH

The first material used to put a roof on buildings to keep the weather out would have been some kind of locally sourced thatch. Straw and reed were the most common, although in certain moorland areas bracken and heather were used. Different styles using straw and reed identified a particular region. Thatch continued to be used for vernacular buildings until replacement materials became available, although in some areas of the English countryside, especially Somerset, Dorset and Devon, thatched roofs have been retained. Good thatch lasts for around thirty years and provides a very warm and waterproof cap for cottages and farm buildings. Thatchers have also introduced distinctive trademarks in their work, including patterning and ridge decoration.

However, there are negatives to thatch. It needs regular maintenance and complete replacement from time to time when it has reached the end of its practical use. Also, thatch is a combustible material, making it a problem regarding fires. Another issue is the opportunity for wildlife to set up home within the thatch, which is why thatch today has a protective wire netting covering so as to avoid this happening. For all the negatives, thatch still has the appeal of the traditional image we all associate with the idyllic country cottage, although practical and economic priorities would see some of the cottages and farm buildings have their original thatches replaced with more modern and low-maintenance materials.

A Devonshire thatched long house, which was common to this area of Devon. This example stands at High Venton, on Dartmoor.

This estate cottage in Osmaston village, near Ashbourne, Derbyshire, shows elaborate finishing touches; note the chimneys and fancy bargeboards. The thatched roof is finished with a decorative ridge. Although the cottage looks old, this would have been a revival style used by the estate owners to create effect.

Devonshire thatched cottages around the village green at Lustleigh. Note the eyebrows to the upper floor windows.

This half-timbered cottage at Coton in the Clay, Staffordshire, features large eyebrows to the thatch over the upper floor windows. Note the growth of green moss on the roof. This thatch is definitely in need of replacement.

STONE

Where stone was readily available it would be selected and cut to large or small tiles or flags. These were then put onto laths supported on rafters and the roof trusses underneath. The common technique was to put the larger stone flags and tiles on first along the line of the eaves. Then the size would be reduced as they approached the ridge. This material lasted well, with only a minimum of maintenance required.