28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

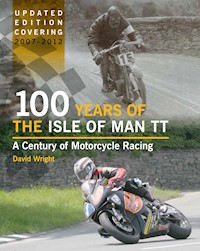

Run over the every-day roads of the Isle of Man for over 100 years, the world-famous Tourist Trophy races have gripped the imaginations of successive generations of motorcyclists. From the earliest days of single-speed, belt-driven machines delivering 5 bhp, to the highly developed projectiles of today offering a fearsome 200 bhp, race fans have thronged the roadside banks and watched in awe as the best racing motorcyclists in the world rode the fastest machines of their day around the twists, turns and climbs of the 374 mile Mountain Course, all in pursuit of a coveted Tourist Trophy. This new updated edition covering the 2007 - 2012 races, reveals the event's colourful history through the high-speed activities of great riders such as the Collier brothers, Geoff Duke, Mike Hailwood, Giacomo Agostini, Steve Hislop, Joey Dunlop, John McGuinness and many others.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 670

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

Copyright

First published in 2007 by The Crowood Press Ltd Ramsbury, Marlborough Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2013

Revised edition 2013

© David Wright 2007 and 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 648 2

Photograph previous page: Rem Fowler. (Courtesy Vic Bates)

Contents

Map of the TT Mountain Course

Introduction

The Isle of Man Tourist Trophy race meeting for motorcycles comprises a sporting event without parallel. For over 100 years, in early summer the island’s principal roads have been dedicated to the pursuit of speed on two wheels over the world-famous 37¾-mile (60.75km) Mountain Course, where riders and machines are tested to their limits in front of thousands of spectators.

The TT is an important part of motorcycling history, having contributed widely to the development of almost every mechanical aspect of the motorcycles we have today, and having been contested by manufacturers from many parts of the world. British companies such as Norton, Triumph, Matchless, Rudge, AJS, Cotton, HRD, New Imperial and Excelsior competed with success, together with foreign entries from the likes of Indian, Moto Guzzi, Husqvarna, BMW, Gilera, MV Agusta, Honda, Yamaha, Suzuki, Kawasaki and Ducati. All sought the prestige associated with winning a Tourist Trophy, for an Isle of Man victory – then and now – says more than any amount of commercial advertising and is guaranteed to promote sales, not only for the maker of the winning machine but also for the associated suppliers of tyres, fuel, oil, brakes and so on.

For riders who achieve a TT win, it usually comes as the realization of a lifetime’s ambition. It also guarantees a boost to an individual’s popularity, career progress and earning power. However, competing for a Tourist Trophy has always been about meeting the challenge of pure road racing, where the nature of the course requires competitors to put aside thoughts of personal safety if they are seriously riding to win. Not all motorcycle racers are prepared to take on the challenge of the TT and some thirty-five years ago racing began the process of polarization that now sees it divided into two widely differing disciplines. On the one hand there is road racing, with its acceptance of natural hazards such as walls and kerbs, and, on the other, circuit racing that incorporates maximum run-off areas and gravel traps. Although there are still riders who happily contest both disciplines, increased specialization means that they usually choose one or the other.

The TT has developed into more than a race meeting and now advertises itself as a ‘TT Festival’. However, racing remains at the core of a fortnight’s two-wheeled activities, and as it reaches its centenary the customary questions will be asked about the event’s future. But that has been the way throughout its existence, for the TT has rarely been free from criticism and change. As always, its strength lies in the fact that riders still seek to race, organizers are still prepared to run this unique event, and the Isle of Man continues to welcome its annual presence. Whatever the outcome of today’s questions and answers, nothing can erase the Tourist Trophy meeting’s 100 glorious years of motorcycle racing history, the highs and lows of which are captured within these pages.

Acknowledgements

The first acknowledgement should be to recognize the splendid vision of the pioneer motorcyclists who created the Tourist Trophy meeting in 1907, both as an outlet for their competitive activities and as a means of developing the early motorcycle from its primitive single-speed, belt-driven format to the sophisticated racers of today.

Amongst present-day enthusiasts for the TT who have helped with information for this book are Geoff Cannell, Bill Snelling and Paul Wright. The archives of the Manx Museum Library have also been a source of information, and the words are much enhanced by photographs supplied by Vic Bates, Ed Cawley, Ron Clarke of Manx Racing Photography, FoTTofinders, Pat East, Wolfgang Gruber, Alan Kelly of Mannin Collections, Richard Radcliffe, Ken Smith, the Vintage Motor Cycle Club and John Watterson. I am grateful to all for their assistance.

David Wright

Isle of Man

1 How It All Began

The Isle of Man was relatively slow to adopt the use of motor vehicles and fewer than fifty were registered for use on its roads in the first few years of the twentieth century. As its principal commercial activities at the time were fishing, agriculture and tourism, not even the most ardent enthusiast of the early internal combustion engine could have predicted that this largely horse-powered Crown Dependency in the middle of the Irish Sea would develop over the next century into the ‘Road Racing Capital of the World’. Rather more predictable was that, among the early users of cars and motorcycles in other parts of Britain, there were some who wished to compete against each other to see who was the fastest driver and who had the fastest machine. With an overall speed limit of 14mph (22.5km/h) on British roads in the early 1900s (rising to 20mph/32km/h in 1904), there were few opportunities for them to do so in legal fashion.

The 52-mile course used in eliminating trials for the Gordon Bennett Cup held on the Isle of Man in May 1904. Competitors covered six laps and the trials also included separate hill-climb and sprint events.

Four Wheels First

Early in 1904 the Automobile Club of Great Britain and Ireland was looking for somewhere to run eliminating trials to choose a team of drivers to contest the Gordon Bennett Cup, a prestigious car race to be held in Germany. As legislation prevented it from organizing such competition over British roads, Club Secretary Julian Orde paid a visit to his cousin Lord Raglan on the Isle of Man in February 1904, with a view to running trials for the four-wheelers over the Island’s roads. Orde borrowed his cousin’s Daimler and set out in search of a circuit that would test machine reliability and driver skill, rather than out-and-out speed. In this he was successful, choosing some 50 miles of the principal roads linking Douglas, Castletown and Ramsey, including the particularly testing Mountain section that climbed from Ramsey to skirt the slopes of Snaefell en route to Douglas.

Amendments to Manx laws were needed before the roads could be used for racing, and Lord Raglan used his influence to speed through the required legislation in spring 1904. Haste was necessary because time was short, but not everyone agreed with the cutting of legislative corners on behalf of motorists and one member of Government expressed the view that ‘it was undignified to hurry the measure through in such fashion’.

After the considerable time and effort spent on preparations, only eleven cars came to the line in May 1904, but a large number of people turned out to watch the associated flurry of motoring activity and the event was rated a success.

Two-Wheelers’ Turn

Motorcyclists gained their equivalent of the four-wheelers’ Gordon Bennett races when they were able to compete in the International Cup race in France in September 1904. As a result, when the cars returned to the Isle of Man in May 1905, the two-wheelers joined them and held a race to decide who would represent Britain in the next International Cup. The race, which was also referred to as an ‘eliminating trial’, was run by the Auto Cycle Club who intended to use the 52-mile course chosen for the cars, but a last-minute decision saw the motorcycles running over a shorter distance of some 25 miles. Their route took the same roads south to Castletown and north to Ballacraine, but then turned east and returned to Douglas (shown by the dotted line on the map) instead of continuing north to Ramsey. Drawing eighteen entries, eleven ‘weighed in’ but subsequent problems saw four scratch before the start. The result was that only seven came to the line and were despatched for five laps of what Motor Cycle described at the time as ‘the first legalized road races for motorcycles ever held in these islands’. Regrettably, only two motorcycles finished their five laps before the roads were reopened to the public at 8am; the three-man team sent to race for the International Cup in France fared even worse, for none finished the event. British motorcycle manufacturers clearly had much to learn about speed and reliability over distance in those early days.

The next International Cup race for motor-cycles was to be held in Austria in July of 1906, but as the cars were not due to return to the Isle of Man until September, the Auto Cycle Club, which could not afford to arrange independent trials on the Isle of Man, used a short course in the grounds of Knowsley Hall in Lancashire to select a British team comprised of Charles Franklin, Harry Collier and Charlie Collier.

Austria won the International Cup in 1906, with Harry Collier being the only British finisher. However, growing problems on the international motorcycle racing scene brought accusations of cheating against the organizing countries, and Charlie Collier later claimed that ‘due to the most glaring breaches of the rules on the part of the Austrian riders and officials alike, the results of the 1906 race were declared null and void’. There was also growing discontent in Britain as to how continental riders were fitting ever larger and more powerful engines into spindly machines that had to comply with an overall weight limit of a mere 110lb (50kg), and there were many who considered that such moves were taking the development of motorcycles in the wrong direction.

Britain’s representatives in the International Cup race of 1906 held in Austria: Charles Franklin (left), Harry Collier (middle) and Charlie Collier (right). The machines they rode were stripped and lightened versions of the ones shown here.

The Tourist Trophy

As early as February 1906 Walter Staner, editor of Autocar (the parent journal of Motor Cycle), proposed at a dinner of the Auto Cycle Club that an international race should be organized to encourage the development of efficient and reliable touring motorcycles, as opposed to out-and-out racers. A few months later a major step in that direction was taken by Henry Collier, Freddie Straight and the Marquis de Mouzilly St Mars. Henry was founder of the Matchless concern and father of two of the British team in the 1906 International Cup: Harry and Charlie Collier. Freddie Straight was the energetic secretary of the Auto Cycle Club, and the Marquis was a French noble with strong British interests, fluent in several languages and a member of the Auto Cycle Club’s organizing committee. Returning by train from Austria after the International Cup in 1906, they fell to discussing their ideas for an event for ordinary touring motorcycles. Envisaging limits on engine size, an easing of machine weights and the setting of petrol consumption limits as a means of controlling speeds, they realized that they were going down the same road that the cars had taken in 1905 when they raced for a Tourist Trophy over the roads of the Isle of Man. Feeling that was the way forward for powered two-wheelers, the Marquis offered to provide a Tourist Trophy for – in words of the time – ‘a race for the development of the ideal touring motorcycle’. Receiving a favourable response, he commissioned the magnificent figure of Mercury mounted on a winged wheel that is now renowned throughout the racing world and is still competed for. It was thus that the Tourist Trophy for motorcycles came into being and was gratefully accepted for competition by the Auto Cycle Club in 1907.

An early photograph of the Tourist Trophy.

Preliminary proposals for the first motor-cycle Tourist Trophy (TT) race were made public in the specialist press in December 1906 and much discussion followed as to the regulations that should apply. The first formal set of rules for the race were published in February 1907 and specified that machines should be ‘of touring type’, have a soundly constructed frame, be fitted with saddle, brakes, mudguards, efficient silencer, tyres of at least 2-inch size, a 2 gallon fuel tank and carry a minimum of 5lb of tools in a toolbox. No weight limit was imposed and the only restriction on engine size was that individual cylinders should not exceed 500cc. Pedalling gear was optional. In addition to the above constructional matters, a rule of particular importance related to fuel allowances, wherein it was proposed that competitors would receive an allocation of petrol at the rate of 1gal for 90 miles of race distance. Following pressure from potential entrants of multi-cylinder machines, the rule was changed so that they received 1gal for 75 miles, single-cylinder machines getting the original 1 gallon for 90 miles. The unintentional effect of this rule was to create two races, one for singles and one for multis – but that raised the question of who was to receive the Tourist Trophy. It was decided that it would go to the winner of the single-cylinder race and Dr H.S. Hele-Shaw offered a trophy for the best performance on a multi-cylinder machine (although it never materialized), while Maurice Schulte of Triumph Motor-cycles paid for gold and silver medals as lesser awards. Entry fees were set at 5 guineas (£5.25) for trade entries and 3 guineas (£3.15) for private runners. Each winner was to receive £25, with £15 and £10 going to the placemen. Most competitors were official factory entries since, quoting Motor Cycle’s respected commentator ‘Ixion’, ‘The trade was at last convinced that nothing but race work could bring our machines up to the continental standard’.

The organizing committee specified a minimum entry number of twenty, but with riders slow to respond there was a risk in early April that the event would be called off. The closing date for entries was set for the middle of May, by when a total of twenty-eight had been received, comprising twenty single-cylinder machines and eight twin-cylinder. Marques such as Triumph, Matchless, Rex, Roc and NSU were represented among the single-cylinder entries, with Norton, Kerry, Bat, Vindec and Rex in the multi-cylinder class. All were single-speed, clutchless, belt-driven models with minimal brakes and virtually no suspension. Very few had been subject to racing over long distances and the event was undoubtedly a great adventure for all involved.

The faded cover of the Programme for the first TT of 1907.

Those pioneers rode motorcycles fitted with an array of controls that would be quite unfamiliar to riders of today’s race machines. It was before the common use of Bowden cables and some had to contend with levers and rods to control ignition settings, air/fuel mixtures, throttle and brakes. Additionally, a decompressor was used when push-starting and a plunger oil-pump had to be depressed at intervals to provide lubrication to the engine on the total loss principle. Riders were required to make dead-engine starts of their clutchless machines: the basic starting technique was to pull on the decompression lever (which lifted the exhaust valve off its seat, thus reducing the compression to push against), heave the machine into motion and, after some momentum had been gained, let go of the decompression lever and hope the simple ignition system would fire the engine into life. Some machines were still fitted with bicycle-type pedalling gear, which could be used to assist starting. Not only were riders required to start with dead-engines, but they also had to be cold engines, no warming-up being allowed.

The Course

It was no surprise that the Isle of Man was chosen as the location of the first motorcycle TT and a course to suit the capabilities of the machines was plotted in the west of the island. It measured just over 15½ miles (25km) in length and competitors were required to cover ten laps, giving a claimed total distance of 158½ miles (255km). Known as the St John’s Course, and later as the Short Course, the start and finish were located opposite the historic Tynwald Hill at St John’s. From there riders travelled in an anti-clockwise direction to Ballacraine, where they turned left and headed north over country roads to Kirk Michael. At Douglas Road corner in Kirk Michael they turned left and followed the coast road south to Peel, threading their way through its narrow streets before turning east and returning to St John’s.

The St John’s Course used for the TT from 1907 to 1910. The stretch from Ballacraine to Kirk Michael is used to this day.

When riders tackled that first race they found none of the smooth, wide, well-drained, tar/bitumen-surfaced roads that we know today. Instead they were faced with narrow, twisting lanes overhung by hedges and surfaced with a rolled macadam that was very loose and dusty when dry, and slippery and rutted when wet. Yet the bravest of those pioneer racers still rode at speeds of up to 60mph (96km/h) on their narrow puncture-prone tyres, occasionally being forced to take a hand off the handlebars to deliver a few strokes to the oil pump or attend to one of the other controls, most of which were fitted to the side of the petrol tank. Attempts to lessen the dusty road conditions by spraying an acid solution called Akonia were ineffective, although an unexpected result was that the solution got onto riders’ clothes and ate holes in riding jackets and trousers.

In the two weeks prior to race day there were loosely organized practice sessions over the course. They were restricted to early morning, but some riders indulged in unofficial sessions, speeding through the narrow streets of Peel at all hours of the day and bringing threats of prosecution if they were caught doing so outside official times. It was not felt necessary to close the roads to other traffic during official practice periods and, to make things even more interesting, a change in the route taken by the cars (who were also racing), meant that the four-wheelers were practising over some of the same roads as the bikes, but travelling in the opposite direction!

Weights and Measures

Although there was no rule restricting the weight of rider or machine, the organizers insisted on weighing both on the day before the race. Using facilities at St John’s railway station, they discovered that machines weighed between 140 and 196lb (63–89kg), and riders tipped the scales at 134 to 166lb (61–75kg).

Among the several modifications made to the originally published rules was the one that required all machines to be fitted with a fuel tank of at least 2gal (9ltr) capacity. Few met the original requirement, so the minimum capacity was dropped to 1¼gal (5.7ltr). The result of the change was to create the need for mid-race refuelling, something that has been a feature of most TT races ever since. At the first running it was decreed that riders had to refuel during a compulsory ten-minute stop at St John’s at the half-way point, when they could also take a rest and refreshment. They were handed their race allowance of fuel in sealed cans before the start and were expected to arrive at the mid-race stop with the wire seals on their fuel tank caps intact. The serious riders among the entry experimented with gearing and carburettor settings during practice to obtain a level of fuel consumption that would allow them to complete the race on the petrol allowed. Rumours spread that some would have to ride at less than full throttle. How much of that was true and how much was gamesmanship designed to mislead the opposition varied from make to make, but there is no doubt that there were riders who had to tune for economy at the expense of speed.

Pushing away from the Start.

The First Race for the Tourist Trophy

Race day was set for Tuesday, 28 May 1907, with the roads of the course being closed to all other traffic from 10am to 4pm by means of the official Road Closing Orders issued under the provisions of The Highways (Motor Car) Act 1905. On an unseasonably cool morning, race officials, riders and spectators gathered at Tynwald Hill in dry, cloudy, but breezy conditions, for the 10 o’clock start. The principal officials had a small tent and table at the edge of the course near the start-line, and blackboards were erected to display riders’ race positions as the race progressed. Wearing their designated armbands, other officials busied themselves in the supervision of the fuelling of machines and in general preparations for the race. Some perhaps felt overly important, for a local newspaper reported that ‘at times the officials in the less responsible positions became somewhat officious’.

The variety of machines gathered to race was matched by the variety of the riders’ clothing, for there was no standard race-wear as there is today. Most wore stout tweed jackets and trousers, although leather jerkins and breeches were also to be seen. Heads were covered with cloth hats, balaclavas or leather helmets held in place with a pair of goggles, and feet were clad in lace-up leather boots of varying lengths. Leather gloves or gauntlets completed the riding kit and the majority of riders carried spare butt-ended inner tubes tied around shoulders or waists, for most expected to have to deal with a puncture at some stage of the race.

Riders ranged themselves in pairs behind the start-line, for the regulations required them to be despatched two at a time at one-minute intervals, with single-cylinder machines preceding the multis. The first pair to the line was Frank Hulbert and Jack Marshall on Triumphs, followed by Matchless-mounted Charlie and Harry Collier, with the remainder of the twenty-five starters behind them. At 10 o’clock timekeeper ‘Ebbie’ Ebblewhite gave the nod, the starting flag twitched and the first two riders heaved their machines into life, or attempted to, for Marshall’s Triumph was reluctant to fire. Indeed, with cold engines tuned for economy, others were similarly troubled, moving one newspaper to tell its readers that ‘the starting of a motorcycle is a very awkward and uncertain business’.

Eventually they all got away. Some ten minutes after the last competitor departed in the direction of Ballacraine, those at the start heard the steady beat of a single-cylinder engine approaching from Peel to complete the first lap. Despite his original starting difficulty it was Jack Marshall (Triumph) who led the field, followed by Charlie Collier (Matchless), both being on singles. Rem Fowler (Norton) was the first to complete a lap on a twin-cylinder bike, with Billy Wells (Vindec) his closest challenger. Less fortunate were W.A. Jacobs (Rex), who retired on the first lap, Oliver Godfrey, who lost time through a puncture, and joint first rider away, Frank Hulbert, who had to stop and change a plug.

The interval method of starting was one that was destined to become a TT tradition, but it required timekeepers and spectators to do a little mental calculation when trying to establish who was leading the race, for it was not necessarily the first man on the road. That was the case in 1907, when at the end of the first lap Charlie Collier led the race on corrected time, even though he was in second place on the road. Charlie continued to pull away from his challengers (soon taking the lead on the road) and by the compulsory ten-minute refuelling break he had a lead of several minutes. T.H. Tessier (BAT) and G. Horner (Royal Cavendish) both ran out of fuel before the break and Oliver Godfrey’s bike burst into flames while being refuelled. A Manx policeman tried to smother the flames with his overcoat but Godfrey’s bike was too badly damaged to continue. Sixteen of the original twenty-five machines were fit to start the second part of the race and all got away. Charlie Collier appeared to have a relatively trouble-free ride at the head of the single-cylinder race, but his nearest rival, Jack Marshall, suffered a time-consuming fall and puncture. Rem Fowler lost the lead in the twin-cylinder machine race on his Peugeot-engined Norton, and both he and his closest rival, Billy Wells, suffered a host of problems. Rem fell off twice, repaired a front-wheel puncture, changed sparking-plugs several times, tightened his drive belt twice and fixed a loose mudguard. But at the end of the ten punishing laps, which had taken more than four hours to complete, it was Charlie Collier and Rem Fowler who finished at the head of their respective fields. There were eleven finishers and last man ‘Pa’ Applebee (Rex) took 5¾ hours, getting to the end just before the roads were reopened to normal traffic. Final results are shown in the table (above).

Reported to have ‘had a great reception as he rode up the victor’ on his family-produced Matchless, Charlie Collier’s ride to victory meant that his name became the first to be inscribed upon the Tourist Trophy. As the promised award for the first multi-cylinder machine did not materialize, Rem Fowler’s efforts went unrewarded in that respect. It was not until fifty years later, at the Golden Jubilee TT of 1957, that the aged winner from 1907 was presented with a specially commissioned trophy in recognition of his efforts of half a century earlier.

Seventy-five years after the first race, the Isle of Man postal authorities issued this commemorative stamp showing Charlie Collier winning the 1907 TT.

Post-mortem

Looking back on the first TT meeting, Charlie Collier’s win was not unexpected, for he was an experienced competitor and, with Jack Marshall, had started as favourite. Charlie clearly got the balance between tuning for speed and economy just right with his single-cylinder JAP engine, as he averaged 94.5mpg (3ltr/100km) for the race (the allocation for singles being based on a consumption limit of 90mpg), while Jack Marshall returned 114mpg (2.48ltr/100km), which suggested that he could have gone faster if his machine would have allowed. ‘Privateer’ Rem Fowler’s win in the multi-cylinder race surprised a few people but, although entered as a private runner, he received the considerable support and attention of James Norton, owner of the Norton concern, before and during the race. Rem’s Norton was fitted with a 671cc V-twin Peugeot engine that delivered a comfortable 87mpg (3.25ltr/100km), but the second man on a twin, Billy Wells, had very little petrol left in the tank of his Vindec at the finish, having consumed it at a rate of 77mpg (3.67ltr/100km), which was very close to the twin’s 75mpg allocation.

Rem Fowler poses with his Norton at the back of the Tynwald Inn after the 1907 TT.

Racing generates many ‘what if’ situations and in their post-race advertising in 1907 Triumph hinted at the result that might have been in that first race for the Tourist Trophy by claiming in respect of Marshall’s performance: ‘The Triumph made faster time than any machine in the race after deducting time lost for repairing punctures’. Racing can also lead to tensions between competitors and Norton took advertising space to contest Triumph’s claim, stating: ‘The fastest machine in the Tourist Trophy was the Norton twin, in spite of misleading statements to the contrary’. Speed was clearly an important factor in the sales appeal of early motorcycles, just as it is today.

The Dunlop Tyre Company was present at the first TT and advertised the success of its products in Motor Cycle.

Light Pedal Assistance

The St John’s Course was chosen to be taxing – but not too taxing – for the single-speed machines competing in the first TT and it was free from any really severe hills. However, the climb out of Glen Helen by way of Creg Willey’s was steep enough to force some riders to jump off and run alongside and caused others to make use of the pedals with which some machines were fitted. The latter action, known in old bike circles as LPA (Light Pedal Assistance), proved contentious and brought complaints from competitors who had not thought to fit them. The race regulations stated: ‘Pedalling will only be allowed for the purpose of starting or restarting in traffic, or at sharp bends or on steep gradients. Excessive pedalling will disqualify’. Among the pedallers was Charlie Collier on his race-winning 3½hp Matchless and, since reports at the time made the claim that sturdy pedalling could add the equivalent of 1hp to a machine’s output for brief periods, it was an increase that was well worth having. Some of the pedallers were even said to have had their legs massaged during the half-way stop, rather like racing cyclists.

The press reported favourably on the running of the first TT, with Motor Cycle describing the course as well calculated to test the machines and find their weak points. However, knowing that not all its readers supported the racing of motorcycles, it wrote: ‘It is useless to say that fast speeds are not to be encouraged, human nature being what it is’, and then went on to explain that the testing of motorcycles to their limits in braking, road-holding, engine revolutions and speed during a race could prove beneficial in eliminating problems from ordinary road-going motor-cycles that were asked to perform at much lower levels. The Isle of Man Times and General Advertiser gave a quite detailed report of the meeting, claiming that ‘thousands of visitors and residents gathered at various points of vantage’ and going on to say that ‘the event passed off most successfully from various points of view’.

What those many spectators at the first TT did not realize was that, in the words of motor-cycle historian James Sheldon:

It was this race which was to provide, in future years, a ready proving ground for every new idea in motorcycling, every development, every angle of design. However right in theory a new idea might be, it was not until it was proved in the Isle of Man that it was accepted.

Racers Return

Motorcycles and cars returned to the Isle of Man in 1908 to compete for their respective Tourist Trophies, arriving in September. Local business-people were happy for them to come in either May or September, since the presence of riders, officials and spectators at those times helped to extend the Island’s tourist season, which was normally concentrated into a few summer months.

The organizing Auto Cycle Club spent the early part of 1908 successfully fighting off challenges to its position as the controlling body of British motorcycle sport and, on the way, renamed itself the Auto Cycle Union (ACU). Its mission also to encourage development of touring motorcycles was confirmed when the regulations for the 1908 TT races were published. Prospective entrants found that pedalling gear had been banned and the petrol allocation reduced, so that single-cylinder machines received 1 gallon for 100 miles of race distance and multi-cylinder runners 1 gallon for 80 miles. Although prize money for the previous year’s event had been raised by benefactors within the trade and sport, for 1908 the organizers widened their funding appeal to include the general public, issuing a notice that read:

Motorcyclists who feel disposed to assist the ACU in awarding some cash prizes to the successful competitors in the Tourist Trophy Race, should forward a postal-order for one shilling or twelve stamps to the secretary of the Auto Cycle Union.

Part of the pre-race procedures involved the testing of machines for exhaust noise and brake efficiency. For those tests everyone moved from the general ‘weighing-in’ area at St John’s to a nearby short but steep hill that led away towards Peel. Machines were required to be ridden up the hill with throttle wide open, and officials stationed themselves on the hill and ‘judged’ if silencers were effective. Returning down the hill, riders had to apply their brakes at a given point and stopping distances were measured to assess efficiency.

A total of thirty-seven entries were received for the 1908 TT and they included two genuine multi-cylinder machines in the form of 4-cylinder models made by the Belgian F.N. marque. Other foreign-made machines in the entry were two Indians and two NSUs, the latter being the first TT machines to be fitted with two-speed engine pulleys, thus giving a choice of gearing. Although single-cylinder machines had dominated the entry in 1907, in 1908 they were just outnumbered by twins/multis when the thirty-three starters came to the line in front of 2,000 spectators at St John’s. The weather was fair, the roads had been ‘scraped and swept to a good state of order’ and, with rider safety in mind,

a body of trained ambulancemen from Douglas, well supplied with stretchers and appliances for the succour of any rider who should be unfortunate to suffer mishap attended with bodily injury, were conveniently disposed around the course.

The only hitch came when the start was delayed for a quarter of an hour to allow the passage of a train across the course at the St Germain level crossing outside Peel.

When the race got under way Jack Marshall (Triumph) moved into the lead, but by half-distance he had lost the position to Charlie Collier (Matchless). Both were on singles and the leader of the multi-cylinder class was Harry Reed on a DOT of his own manufacture. Jack Marshall rode well and recovered the lead in the latter part of the race. He had good reason to do so, for a newspaper report claimed ‘there was a whisper of romance about him that a very nice girl had promised to be his bride if he won the race’. Win he did, bringing his Triumph home ahead of Charlie Collier, thus reversing the finishing positions in the single-cylinder race of 1907. Triumph made much of their victory and the publicity earned by Marshall’s winning ride was known to have boosted the sales of Triumph motor-cycles in what was a flat market in 1908.

This was the Triumph machine logo at the time of Jack Marshall’s win in 1908.

Harry Reed held on to his lead to win the multi-cylinder class from Bill Bashall (BAT), but 1907 multi-cylinder class winner Rem Fowler was forced to retire early in the race. The reason for Rem’s retirement offers a glimpse of the basic nature of those early machines. He used a twin-cylinder engine of Norton’s own design (modelled on the previous year’s Peugeot engine) and it featured non-adjustable tappets. The basic steels in use at the time allowed the valves to stretch in use and, with non-adjustable tappets, all clearance could sometimes vanish after 20 miles (32km) of racing. To cope with the problem, Rem planned to carry a 6-inch file, so that he could stop during the race, file down the valve tops, recover some clearance (and compression) and continue at speed. Unfortunately, he forgot to carry his file and, in his words, ‘it soon overheated, lost its compression and ran to a standstill’. Not only did valves stretch but they sometimes broke. Riders in those early races usually carried a spare valve that, at the risk of burnt fingers, they could change at the side of the road in about ten minutes.

A twin-cylinder Norton engine similar to the one used by Rem Fowler in 1908.

The engines of the early TT racers were ‘all-iron’ and had poor heat-shedding qualities. Hard riding increased the chance of overheating, which could result in loss of power, failure of components and seizures. The climb out of Glen Helen needed every scrap of power available if riders were to avoid having to jump off and run alongside – something that could be very wearing if done on each of the ten laps. The 1908 winner, Jack Marshall, told how he eased the throttle on the stretch from Ballacraine to Glen Helen so that his Triumph would deliver maximum power for the ascent of Creg Willey’s. The Rex concern even came to an arrangement with a lady who lived in a cottage at Laurel Bank (just prior to Glen Helen), whereby she left buckets of cold water outside her cottage. This allowed the Rex riders to stop and ladle cooling water over their engines before rejoining the race and building up speed to tackle the subsequent hill.

Rules are Rules

Every TT generates points of contention. These are usually between riders and organizers, and sometimes between individual riders, with the organizers called in to act as arbiters. In 1907 the big issue had been that of excessive pedalling and in 1908 it was that the organizers had used very brittle wire to seal competitors’ fuel caps. At least that was the claim made by several competitors who arrived at the finish with their seals broken. Unable to find proof of illicit refuelling the organizers could do nothing, even though some of those who arrived with their seals intact clamoured for the disqualification of the rule breakers. Another indication of how the rules were pushed to the limit and beyond, from the earliest days of TT racing, comes in the words of Noel Drury who finished 4th in the multi-cylinder race in 1908 on what he described as his ‘genuine touring’ machine. Noel later expressed surprise that some of the leading machines featured ‘cycle racing saddles, 2-inch mudguards made of aluminium sheeting, no lamp brackets or tool holders, short handlebars, etc’.

Noel Drury on his JAP-powered machine for the 1909 TT: ‘I was put out of the race by hitting a large boulder which fell out of a loose wall around a bend in Glen Helen and I came a purler, bending the forks and other damage’.

Press comments

The motorcycle press had a vested interest in praising the machines of the day but the Manx press could afford to be more critical. As well as supporting the principle of racing motorcycles over Manx roads, however, a local newspaper also recognized the attraction of the motorcycle as a means of transport: ‘A self-contained vehicle capable of travelling nearly 160 miles in 4 hours, with one brief halt for fuelling, is bound to attract the favour of a numerous class of travellers’.

Despite support from some elements of the press and the much-increased numbers in use, powered vehicles were still not particularly welcomed on British roads, where four-legged horsepower still held sway. Prior to the 1908 TT, The Times, Daily Mail and other national newspapers ran articles criticizing the racing of cars and motorcycles over the public roads of the Isle of Man.

This is the sort of emporium that early riders would patronize. Motorcycles were even manufactured in such small garages. Note the cans of fuel stacked outside in those pre-petrol pump days.

Before the running of the first TT, competitive events for motorcycles in Britain had largely been confined to hill climbs of dubious legality, run, as one magazine of the day put it, ‘whenever the goodwill of the police permits’. There were also speed events on boarded cycle race-tracks, but only those who ventured abroad could legally participate in races on the road. In early 1908 Brooklands held the first race for motorcycles on its new, purpose-built race track in Surrey, and it was to become a centre for competition and the development of motorcycles for the express purpose of racing and record breaking. As a result of the competitive climate created, there were factions in the ACU who sought to reduce the touring emphasis of machines used at the TT. These were largely resisted for 1909, but there were three important changes to the rules of the TT run that September. Most significant was the abolition of restrictions on petrol allocation. This meant that machines could now be tuned for maximum speed, a process that was also helped by the removal of the need for engines to race with silencers fitted. Finally, instead of running races for single and multi-cylinder machines, the event now became one race, with single-cylinder machines restricted to a maximum capacity of 500cc and multis to 750cc.

Which Way?

In Motor Cycle, the principal voice of motor-cycling in its early years, ‘Ixion’ later wrote of 1909:

Nobody felt sure what form motorcycles would ultimately assume. The multi-cylinders offered smoother running and easier starting; the singles were cheaper and lighter. Hill-climbing, the main bogey of the hobby, was as yet unsolved. Some people advocated gears, others opposed them.

The uncertainty shown by early manufacturers is understandable, for a glance at the vast range of motorcycles available on today’s market shows that the all-purpose machine that will suit every user has yet to be designed.

Prior to the 1909 TT, practising was allowed on fourteen weekday mornings (when silencers had to be used). Among the fifty-seven race starters were James L. Norton, the forty-year-old proprietor of the firm carrying his name, and Walter O. Bentley (Rex), who was later to manufacture motor cars bearing his name. The famous continental rider Giuppone (Peugeot) was riding for the first time and the winner’s prize money was increased to £40. There were no longer any restrictions upon the amount of petrol that a competitor could use, but refuelling was restricted to a prescribed point at the start/finish area and another located some 200 yards from Douglas Road corner on the outskirts of Kirk Michael.

The appearance of a Scott in the race heralded the first TT racing two-stroke and, although it did not particularly impress with its performance, spectators liked the novelty of its rider starting his engine by way of a kick-starter and the sound of its distinctive exhaust note.

With the change in rules that created just one race for 1909, multi-cylinder machines became eligible to win the Tourist Trophy for the first time and two riders of V-twins seized the opportunity to head the rest of the field. G. Lee Evans took his 5hp Indian into the lead and held it for five laps before Harry Collier took over on his 5hp Matchless and rode to victory by almost four minutes, recording an average speed for the race of 49.01mph (79km/h) and setting the fastest lap at 52.27mph (84.1km/h). Harry Collier’s fastest lap was a substantial 10mph faster than the previous year’s winning speed. Just how much of that increase was down to machine development and how much due to the abolition of petrol restrictions and ability to run without silencers will never be known, but it was significant that out of fifty-seven starters, only nineteen finished the race. Some observers put the reason for this down to the fact that, with fuel economy no longer a factor, bikes had been tuned for out-and-out speed, thus increasing the stress on engines and reducing reliability.

Harry Collier at speed on his Matchless.

Here to Stay

By 1910 the demand for motorcycles was booming, with Triumph reported to be making a hundred machines a week. However, it was a competitive market and manufacturers were aware that one way in which they could demonstrate the reliability and competitiveness of their products to potential customers was in organized sporting competitions. Long-distance trials were popular, as were hill climbs, but as there were still only limited opportunities for racing their products on the roads the Tourist Trophy event on the Isle of Man quickly established itself as a very effective showcase for sporting motorcycles. Well supported by riders, manufacturers and spectators, a Manx newspaper greeted the end of the May event in 1910 with ‘Magnificent Contest of Athletes – Great Test of Human Endurance’, and the motorcycle press already recognized that ‘Nothing brings forward the weak points in an engine and its construction better than a race like the TT’.

Other writings in the local press told that practice would take place ‘from daybreak to seven am’ and that ‘anyone riding the wrong way around the course will be disqualified from the race itself’. Those early-morning sessions were full of incidents, with reports that:

Groves on the Ariel buckled a wheel; A.E. Woodman, all the way from New Zealand, had a nasty smash near Kirk Michael when a puncture threw him into a wall; Alexander on the Rex had a narrow shave when the rear wheel punctured at speed and he had extreme difficulty in staying on his machine – to get home he stuffed the tyre with grass. Godfrey on the Indian seized when his piston broke and he was tossed from his mount; Bert Yates of the Humber team also departed from his machine when the rear brake came adrift and jammed the rear wheel; Brewster drove his machine straight into a brick wall at Ballacraine – his machine is a total wreck.

Despite general awareness that TT racing took a heavy toll on men and machines, entries surged to eighty-three for 1910 and the organizers considered limiting acceptances to seventy. They decided to allow everyone in, calculating that there would be some non-starters, and that proved to be the case with seventy-three competitors eventually coming to the line. Among these were thirty-nine riders on twins who, in another rule change, were now limited to a maximum engine capacity of 670cc. There were also an encouraging thirty private entrants.

An advertisement for H. Collier & Sons Ltd and its Matchless machines.

Mechanical advances saw chain drive featured on Indian, Scott and a Rex, while Zenith used their patent Gradua variable gear. Some of the Humbers had overhead valves and there were experiments with dry-sump lubrication. Despite the organizers’ attempts to reduce the performance differential between singles and twins by reducing the latter’s permitted engine size to 670cc, twin-cylinder machines showed that they still had the edge over the singles. It was the Collier brothers who again moved to the front of the race at about half-distance on their Matchless twins, and they finished with the major honours – Charlie was first and Harry second – being followed home by a batch of Triumph singles among the twenty-nine finishers.

Charlie Collier

and Harry Collier were the most successful of the TT pioneers.

In the first four years of its running, the Tourist Trophy event had gripped the imagination of the motorcycling world. Entries increased year-on-year as more competitors took up the challenge, but results showed that the winning formula at the TT was not one that relied simply on out-and-out speed. It was the successful Collier brothers who showed that all-round riding skills, speed allied to reliability, plus experience, organization and racecraft, made a combination that was difficult to beat. Other riders had led races, but it was the Colliers who, by successfully pacing themselves to several well-deserved victories, were the star performers in those early Island races.

2 A Mountain to Climb

The ACU, the organizing body for the TT meeting, had seen the number of entries for the races grow each year from their first running in 1907, and by 1911 it was confident that it operated from a position of strength and could shape the event in the manner of its choice. Showing considerable vision, despite opposition from manufacturers and riders, it moved the races from the relatively flat St John’s Course to a distinctly more testing one that gave a lap distance of just over 37 miles (60km) and incorporated a 1,400ft (425m) climb from sea level to skirt the northern flank of Snaefell. The adoption of what quickly became known as the Mountain Course was a move that, according to Motor Cycle some years later, ‘drove the whole motorcycle industry to develop engines of greater flexibility and to equip them with reliable and efficient variable gears’.

On the approach to the 1911 TT, manufacturers worried about how their existing big single- and multi-cylinder machines would cope with the demanding new Mountain Course, but the ACU had no such concerns and showed it by creating an additional race for singles up to 300cc and multis up to 340cc (resisting manufacturers’ calls for these smaller machines to be allowed pedalling gear). Thus two separate races were run in 1911 on different days and they were given the titles of ‘Junior’ (run over four laps) and ‘Senior’ (five laps). They attracted 104 entries, with the split between the classes showing thirty-seven Junior and sixty-seven Senior runners. Entry fees were double those of the first TT in 1907, being a substantial 10 guineas for trade and 7 guineas for private runners. In a further attempt to even out the performance differential between singles and multis in the Senior race, the capacity limit of multis (generally twins) was reduced from 670 to 585cc.

Manufacturers had received a foretaste of the demands that the climb of Snaefell would make on their machines when, just after the 1909 and 1910 TTs, the ACU ran a 6-mile (9.6km) hill climb from the sea-level outskirts of Ramsey to almost the highest point on the Mountain Road at the Bungalow Hotel. Several firms experimented thereafter with variable gears, and on machines that adopted them for use in the 1911 TT there could be seen examples of epicyclic hubs, epicyclic engine-shaft gears, sliding countershaft gears and expanding pulley gears. Such ability to vary the gearing, if only modestly by later standards, helped overcome the previous situation where the single gear fitted had to be a compromise between being high enough to offer the best possible speed on level going, without robbing the machine of reasonable hill-climbing ability.

Riders knew there was another transmission problem to cope with when tackling gradients, for the belt drives fitted to most early machines to convey engine power to the back wheel tended to stretch in use, thus allowing the belt to slip under load. Some makes used a jockey-wheel to help maintain tension, but problems of belt grip/slip could be aggravated by wet conditions, or by the belt getting coated in oil from the usually less than oil-tight engines of the day. It was not unknown for a belt to break in use and most competitors carried a spare (pre-stretched) belt during a race, plus the means to repair a broken one.

P. Owen is ready to race his belt-driven Forward in the Junior race of 1912. The Forward Company’s venture into motorcycle manufacture was short lived, for it found it more profitable to specialize in the making of drive belts and their associated fasteners.

With a lap of the new Mountain Course for 1911 extending to more than 37 miles, riders were keen to get in as much practice as possible and a pre-race report of the time said: ‘Once again between the hours of three and seven in the morning, when most people are wasting these good hours in bed, scenes of excitement will take place, and the roars of the engines will be heard.’ Those were clearly the words of a motorcyclist and it is doubtful if people living adjacent to the course spoke of the early morning practice sessions with such enthusiasm. Before practice riders were told: ‘All dangerous parts of the course will be marked by banners some distance from the point of danger’.

Machine reliability was a necessity for those seeking TT success and New Hudson was said ‘to have everything brazed on and every nut is split-pinned’. Despite the striving for reliability, most companies experimented with some new aspect of design during practice. In attempts to lighten and improve lubrication of pistons, Norton fitted one with thirteen circular grooves (excluding ring grooves) in their single-cylinder models, while Zenith lightened their pistons with holes in the walls. Brown and Barlow appeared with a new variable-jet carburettor that was chosen for use by several riders, and former winners Harry and Charlie Collier were back seeking further glory on Matchless machines fitted with a variable pulley gear offering belt-driven ratios between 3:1 and 5:1.

A problem with some variable pulley systems with a normal fixed-length drive belt was that as the size of the pulley was changed to alter the gearing, the belt could lose tension and slip. Various methods were used to deal with this problem. Zenith overcame it with their ‘Gradua’ arrangement, which moved the rear wheel to shorten or increase wheelbase as pulley diameter changed. The Rudge concern was uncertain what form of gearing to use in 1911 and a pre-race report said, ‘The Rudge TT models will be of the ordinary standard pattern as far as outward appearance goes, but it is not yet decided whether a direct drive, clutch or two-speed gear will be used. Probably one of each type will ultimately be adopted.’ In the final run-up to the TT, Rudge designed an improved form of variable pulley system that allowed constant belt tension to be maintained: although it allowed only a variation in gearing of 5¾ to 3¼ to 1, they named it the ‘Multi’.

Several Rudge-Multis being prepared on the Island for the TT.

The American Indian Company was another manufacturer with variable gearing, and its system was advanced for the time, comprising a two-speed countershaft gearbox, clutch, and all-chain drive. It was a system that greatly reduced the problems associated with the climbing of hills and one that paid rich dividends in the Isle of Man in 1911, for their twin-cylinder machines (with engines scaled down to the 585cc TT limit and featuring overhead inlet and side exhaust valves) came home a triumphant 1-2-3 in the Senior TT. Englishman Oliver Godfrey was the man to get his name inscribed upon the Tourist Trophy by taking first place from his team-mates Charles Franklin and Arthur Moorhouse, and their red Indians finished ahead of machines from Ariel, Bradbury, Zenith-Gradua, NSU, Rex and others.

A copy of the original Tourist Trophy was made to award to the winner of the newly created Junior race, and Percy Evans was the first recipient after riding his V-twin (Humber) into first place, nine minutes ahead of Harry Collier (Matchless).

The start and finish point of the 1911 races in Douglas was located on a flat section of road between the bottom of Bray Hill and the descent to Quarter Bridge, where the latter’s downward slope was very welcome to those who had difficulty bump-starting their machines. Clerk of the Course Mr J.R. Nisbet controlled affairs at the start with the aid of a megaphone, scoreboards were erected at the side of the road, the timekeepers had a small wooden shed to work in, and the press occupied a room in an unfinished cottage close to the finishing line. However, there was no room for a riders’ ‘replenishment area’, so official refuelling points were created at Braddan and Ramsey.

Charles Franklin sits astride his Indian before the start of the 1911 TT, in which he finished in second place. Note the spare butt-ended inner tubes tied around his waist in case he needed to repair a puncture.

Although it is not possible to make a direct comparison between the old and new TT courses, it is worth mentioning that Oliver Godfrey’s average race speed over the Mountain Course in 1911 was 47.63mph (76.65km/h), while Charlie Collier’s winning speed on the easier St John’s Course in 1910 had been 50.63mph (81.48km/h).

Outside Assistance

In what had become the customary post-race squabble over non-compliance with race regulations, Charlie Collier (Matchless), who was initially awarded second place in the 1911 Senior race, was disqualified for taking on petrol at other than the officially permitted refuelling points, and Jake De Rosier (Indian) received the same treatment for borrowing tools to adjust his valve-gear out on the course. Their actions came under the heading of receiving ‘outside assistance’, an expression that has become enshrined in TT lore as a forbidden activity. A rider was only permitted to carry out repairs on the course using the tools that he carried with him, but in the quest for lightness and speed some riders carried fewer tools than they had previously been obliged to do by the race regulations. TT history shows that the receipt of ‘outside assistance’ has resulted in the disqualification of many other riders down the years, several of whom lost race wins as a result.

Commercial Pressures

Even from the earliest days there was a strong commercial aspect to the TT races. While manufacturers entered knowing that racing yielded useful practical lessons in design and construction, they soon became aware that mere participation in a TT race raised the status of their products and increased their appeal to many potential buyers in what was a crowded but, by 1911, a profitable market. The esteem earned by TT participation was also sought by associated suppliers such as petrol and tyre companies (known as ‘The Trade’), and they were prepared to pay to have their names linked to TT success. The recipients of such payments were usually the successful riders and a report in Motor Cycle in 1911 opined that ‘it is worth nearly £200 to a trade rider to win the Tourist Trophy. Apart from the £40 cash offered by the ACU, a windfall from the makers of the tyres, belt, magneto, carburettor, petrol and the oil employed by the winning machine usually follows’. With such rewards available, it is little wonder that riders sometimes attempted to bend the rules by accepting ‘outside assistance’ to get to the finish.

The 1911 TT performance of Indian and other machines fitted with variable gears provided a convincing demonstration of the way forward for the motorcycle industry, and entries for the 1912 Senior TT featured only one single-geared machine. In yet another change of rule regarding engine sizes, the upper engine capacity limit for the Senior class was set at 500cc for all entries, singles or multis, and a similar ruling applied in the Junior, where the upper limit was set at 350cc. But all was not well on the organizing side, for there were differences of opinion between the ACU and British manufacturers over the running of the TT. Some of the latter boycotted the 1912 event at the end of June, and entries fell to twenty-five Juniors and forty-nine Seniors.

In an overview of the motorcycling scene in 1912, the British press considered that ‘The industry has settled down into a comfortable state of energetic prosperity’. On the run-up to the TT, however, it stressed the importance to the British motorcycle industry of recovering the Tourist Trophy from the foreign victor of the previous year.