Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Aniara

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

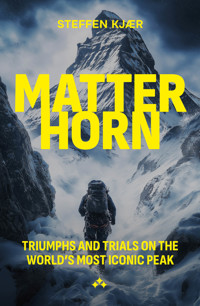

Discover the gripping story of one of the world's most iconic mountains in Matterhorn by Steffen Kjaer. This thrilling book takes you on a journey through daring climbs, breathtaking views, and the life-or-death challenges faced by mountaineers who have tried to conquer the legendary Matterhorn. Known for its striking beauty and deadly risks, the Matterhorn has captivated climbers for over a century. Kjaer explores the physical and mental endurance needed to scale this formidable peak, and the triumphs and tragedies that have defined mountaineering history. Follow real-life accounts of climbers battling extreme conditions, learn about acclimatisation, altitude sickness, and the essential techniques for tackling this majestic mountain. Whether you're a seasoned climber or just fascinated by dangerous peaks, Matterhorn is an essential read. Steffen Kjaer's storytelling brings the mountain to life, making you feel every step and every moment of triumph or defeat. Embark on a journey that challenges not just the body, but the very limits of the human spirit.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 245

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Matterhorn

Steffen Kjaer

Copyright © 2024 by AniaraTranslated by Aniara [email protected]

All rights reserved.

No portion of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher or author, except as permitted by U.S. copyright law.

Contents

Preface

Spectacular! I really cannot think of a word that describes the Matterhorn better. No other mountain in the world has been subject to more attention and fascination than the perfectly shaped Matterhorn since the dramatic first ascent in 1865. Since that day, the drama and the myth have created a unique interest in this mountain, which has probably caused more deaths than any other mountain in the world.

For Brian Jorgensen and I, the decision to attempt to climb the Matterhorn was made with equal measures of fright and admiration. Looking back on our climb, we have both learnt that fascination and horrifying events often go hand in hand.

I am well aware that around the world there are mountains which, technically, are much more difficult to climb than the Matterhorn via the Hörnli Ridge. This book is not written to compare our endeavors with those of others. Rather, I have aimed to tell the story of a mountain that is so spectacular that any mountaineer has got to have it on his or her tick list. Anyway, it was on our list, and so we decided to pursue our dream…

Warning

This is not a guide book, and it is in no way intended as a guide for other climbers. Places and routes are described from my own experiences and will most likely be experienced differently by any other. In the same way, techniques and use of equipment were chosen and used in very specific situations where others may have chosen differently.

Any type of climbing and mountaineering is dangerous. The dangers are everywhere and may very well result in serious injury or death.

The mountains mentioned in this book have all claimed their victims, and nothing indicates that this is going to change in the future. Climbing and mountaineering are dangerous pastimes, and they demand mental and physical fitness, solid background knowledge and a range of skills and equipment to minimize the risks.

To the inexperienced, it may prove hard to determine which knowledge or skills and equipment are necessary to climb a given route or mountain. I therefore recommend that anyone who wants to try his or her hand at mountaineering should participate in approved courses with certified instructors.

Introduction

'Although it is terrifyingly huge, I’m so fascinated by this mountain', said Brian, when we met one evening in March to plan for the coming summer’s climbs. His words were embodied by my thoughts. There was no doubt that the Matterhorn would be our greatest challenge to date.

Since our successful ascent of Mont Blanc the year before, we had discussed several climbing projects, but they had all just been loose ideas. Subconsciously though, I believe we both had decided long ago that this summer would be dedicated to the Matterhorn.

We had read the article, ‘When the Unthinkable Happens,’ by Soren Pedersen. Who, together with Allan Christensen, tried to climb the Matterhorn in the late 1990s. The article was printed in the Danish outdoor magazine Adventure World and describes a dramatic climb brought to a sudden end when the two Danes witness an Italian guide fall to his death right in front of their eyes. Having experienced this, Soren and Allan decided to turn back, and they have never returned to finish where they left off that day.

Even though I have had numerous chats with Allan when we have met on our annual ice climbing trips to Norway, I have never heard him talk about the Matterhorn. I therefore decided to give him a call one day to learn about the general conditions on the mountain. Some days later, I also contacted Soren to get his opinion. Naturally, none of them were able to talk about the last section of the climb which they had left unexplored, but they both confirmed the information from the guidebook: a labyrinth of loose rocks and difficult route finding.

Weeks went by, and as we gathered information about the mountain, my expectations became overwhelming. I felt convinced that we, technically and physically, had what it would take to be capable of climbing the mountain, but I was also well aware that a successful attempt on the Matterhorn would require all the concentration we could possibly muster. A single mistake could be fatal.

Brian and I know each other well. We have been climbing together for four years, and we have spent many months together during our trips to Sweden, Norway, Bulgaria and France. Through the years, we have spent hours, even days, discussing our experiences as well as the risks involved in climbing. We have matched our ambitions, and we share a similar line of thought when it comes to safety. Together, we have acquired the necessary climbing skills on rock, ice and longer alpine routes on snow and mixed terrain. However, compared to our earlier experiences in the Alps, the challenge of the Matterhorn would primarily be sustained rock climbing and difficult route finding: we had more than 1200 meters of steep climbing coming to us in the thin mountain air.

We decided to use a couple of extended weekends to prepare specifically for what we expected to meet on the Matterhorn. One training weekend took us to Utby near central Gothenburg, Sweden. On a parenthetical note, a raven here ate all our food supplies while we had fun on the rocks. Every little bit! Stupid bird! We spent another weekend in Nissedal in southern Norway which we knew to be a good area to practice route finding and arrange belays. Unexpectedly, we also learnt the value of keeping calm when under pressure. It is not always a simple matter to find the easiest way back after a long day’s climb! And on the classic route, ‘Via Lara’, we got a bit more exercise on the descent than was planned for. Like so many before us (as we have later been told), we had gotten confused by the numerous cairns, and therefore we spent four long hours on the return journey. Through pouring rain, getting our trousers torn by the dense scrub and taking many steps in vain, we reached our car – three hours later than the time those familiar with the route would have arrived at. Through the years we have had many similar experiences, but we never blame each other for the decisions made while on the way. Instead, we evaluate the situation afterwards to aim to be better equipped for future challenges.

During our trips, we spent the evenings discussing preparations for summiting the Matterhorn. Actually, it was unnecessary to confirm our unspoken agreements, but still we repeated them to each other: if one wanted to turn back, we both turned back; we were to be open about our physical and mental conditions on the mountain in order to support each other and utilize our resources the best way possible.

While the trips to Sweden and Norway had offered good and interesting climbing, the days outdoors in the company of Brian had most of all fuelled my yearn to get out there, and whetted my appetite for more challenges and experiences.

I picked up Brian at the train station in Kolding in southern Denmark, where he met me with a broad smile full of expectations. We were pleased and excited, and as was usual practice, we hurried into the car and headed off towards our goal without bothering each other with unnecessary questions concerning the packing list.

The Jeep took in kilometer after kilometer while Brian read out loud from different internet printouts of prior attempts on the Matterhorn.

‘Can you hand me your Passport,’ I said to him as we approached the German border. He became very still!

‘I think I forgot it,’ he replied and asked if I thought it would be a problem. I didn’t, so we went on. Germany was no problem. It was not until the Swiss border that Brian really started to sweat.

Responsibly I promised to divert the attention of the policemen at the checkpoint by asking silly questions about the road toll. It was a good plan: the policemen got so upset with me not having cash ready for the sticker to put in the windscreen of the car that they told us to go to a small office nearby. Luckily, they spent so much energy telling us off that they forgot to ask us about our Passports. The operation was a success, and Brian and I agreed that we could probably talk our way out of the country again should it be necessary.

After nearly 1400 kilometers, we arrived at 9 pm in the small Alpine village of Täsch where we had planned to spend the night until we could take the train to Zermatt the next day.

Zermatt lies at the foot of the Matterhorn, and it has long ago had to deal with the consequences of being a popular destination for mountaineers and tourists. Thus, cars have been banned in this town, and visitors as well as goods are taken the last ten kilometers from Täsch to Zermatt by train.

Unfortunately, we had to wait until the next day to continue our journey and to get our first sight of the Matterhorn.

Arrival in Zermatt

Sunday, June 29th

We race each other to get out onto the platform at the train station. Besides the tent and our monstrous backpacks, we are carrying sleeping bags and mats, smaller backpacks for the summit attempt and large shopping bags filled with freeze dried foods. Heavily loaded, we stumble out into the city square from where we try to position ourselves to get the first live peek of the Matterhorn. Even though I have seen hundreds of photos of the mountain, I am overwhelmed by the sight. It’s amazing!

‘It’s so beautiful,’ I think out loud while I dump my backpack on the worn cobblestones.

‘Yes, and huge,’ answers Brian.

He is right. Thoughts are rushing through my head. I actually struggle to control the different moods that wash upon me. At first, I am consumed with awe, then enthused with happiness, and finally the doubt creeps in: will we really be able to climb such a demanding mountain? Will the weather conditions give us the necessary window to push for the summit?

‘I’ll pop down to find a local weather forecast,’ says Brian, and rushes off leaving all the bags he has been carrying next to mine.

There is a terrible stink in the square, and I wonder what it is until I see the contents of the gutter behind me. The sheer amazement that struck me when I saw the Matterhorn has caused me to drop my pack beside a pile of horse droppings. Not far from me, three stagecoaches await rich tourists who probably need rides to the best hotels in town. I am amused by the unusual town life. Everywhere, small electric cars are in silent motion: some deliver tourists to hotels at the other end of the street, others deliver mail and groceries. A Japanese tourist guide has gathered his group around him and seems to be explaining practicalities and the programme of the day. Everything is said through a radio: the guide speaks in the microphone of his headset, and the tourists in front of him receive his advice through their earphones. It looks fancy!

‘Well, are we ready to go?’ asks Brian and tells me that the campsite is located 300 meters down the road.

On the way, he points out the tourist information office where he has found the weather forecast for the coming 5 days. I am excited to find out what kind of weather to expect, and I question him as we walk. While there is some uncertainty related to the forecast, tomorrow seems promising enough: only a few clouds and no wind. We are discussing whether or not to start our first acclimatization trip tomorrow instead of waiting.

‘This must be Zermatt’s campsite then,’ I say to Brian as I point to a number of small tents behind a shed.

The shed happens to be the sanitary and kitchen facilities for the site and also the office of Richard, a retired mountain guide who now runs the campsite. On the site, which is about half the size of a football ground, there are already many tents and climbers, even though it is still early in the season. We greet them and start to unpack the tent. Behind us are two Germans. They look relaxed and seem to accept that their lunch has been disturbed by our arrival and the mouth organ playing Japanese group behind them.

‘It’s so incredibly big,’ says Brian as we later lie on our mats on the grass and gaze towards the Matterhorn.

I can only agree with him. It’s absolutely amazing. While the burner is hissing away and we await a cup of well-deserved coffee, we discuss the route on the mountain. We are both surprised by the less than expected amount of snow on the ridge. During planning, we had been somewhat worried about deciding on the first two weeks of July for our trip. The chance of good weather in the Alps is normally higher later in the season.

I ask about the details in the weather forecast, and Brian explains that after tomorrow there will be several days with clouds and precipitation. That, of course, is not so good, but we will just have to be satisfied with what promises to be a good day tomorrow.

‘Where do you think we should go tomorrow?’ asks Brian.

Before I have time to answer, my attention is caught by two climbers who, marked by the sun and by fatigue, drag themselves onto the campsite. I wonder whether they have climbed the Matterhorn, and I look at Brian who seems to be sharing my thoughts. Poor guys! They hardly manage to dump their bags before I am all over them with questions. Luckily they seem to appreciate our interest, and they tell us their story.

Chris and Will are both in their early thirties and from England. They met in Zermatt a couple of weeks ago, and since none of them had a climbing partner, they decided to climb together. They tell us about their climb on the Matterhorn and solemnly agree that they have just experienced the toughest day of their lives – what encouragement that is! We ask about the conditions on the route and try to make sense of their explanations and advice. They suggest that we should try to get some information from Richard, the owner of the campsite, who, supposedly, has climbed the Matterhorn several hundred times through his almost 30 years as a guide. This is definitely something we will do. We congratulate them again and withdraw to our own tent where we dig out the guide books and start to plan the next few days of acclimatization.

From the literature and from our own experiences in the Alps, we know all about how important it is to accustom the body to the thin air one meets in the high mountains. We have many a time come across mountaineers suffering from altitude sickness due to poor acclimatization. Most recently, on Mont Blanc, we witnessed a Spanish girl with acute symptoms of altitude sickness who was being assisted down by a guide.

It seems an obvious choice to make the Breithorn the target for our first day. With its 4164 meters and location next to the Klein Matterhorn lift, it is the most easily approachable 4000’er in the Alps. This is also the reason why it is a highly regarded one-day project for ordinary tourists who, accompanied by a guide, can make it to the summit in a few hours. The main purpose of our attempt tomorrow is first and foremost acclimatization. We do make an effort, however, to find a different route to the summit than the somewhat trivial normal route, in order to make the climb more interesting. We decided on a slightly steeper route to Breithorn Central Summit as our objective for the first day at altitude.

‘If we’re to make it to the shops before they close, we’d better get a move on,’ Brian suggests.

It is definitely not the first time we have forgotten everything about time and place as we sit with our noses buried in books and maps planning future climbs. As we still need to buy a detailed map and purchase rescue insurance, we must get going.

As we approach the bookshop, we discuss the necessity of buying yet another map. We usually manage with the photos and descriptions in the guide books. We do, however, agree that we need good maps of the area in order to be able to find our way should we get caught in the clouds or in a storm.

Poor Brian! In the book shop he has to put up with my climbing-gear-and-books-syndrome. I always get absolutely euphoric when I am let into shops with climbing gear, and this particular one is full of cool books of great climbs, guide books and maps, too. We end up settling for only one map, which covers the area of the Breithorn and the Matterhorn, along with the indispensable two volumes of Selected Climbs. These guide books are organized like the ones we know from the Mont Blanc area. They offer a rich supply of routes of varying levels of difficulty, information about special conditions and approaches and details about the many alpine huts scattered all over the area.

My good friend Mikkel has explained the requirement for mountain rescue insurance for the Zermatt area. He has told us that, as opposed to some other countries in Europe, you will be charged with all expenses related to being rescued in the mountains in Switzerland. We have never been in a climbing accident in which we needed rescuing, but the 25 euros for the policy seem too little to save should the unfortunate happen.

On our way back to the campsite, we notice a giant cloud that covers most of the upper part of the Matterhorn; exactly as I know it from the many photos of the mountain I have seen while surfing the Internet.

On the campsite we meet Richard, who is making his evening rounds. He takes time to explain the current conditions on the mountain. He tells us that the Hörnli Ridge has probably not been better in 20 years. Normally the route would be covered in snow, but as it is now, he reckons we can climb most of it without crampons. Splendid!

We are quite happy with the outcome of our first day in Zermatt. We have both made the necessary purchases and received heaps of useful information. With above average enthusiasm, we thus approach the last task of the day: cooking!

The First Ascent

The first successful ascent of the Matterhorn was nothing short of spectacular. It is a legendary story that reminds us about the thin line between success and tragedy. In principle, every time a high mountain is climbed successfully for the first time, it is an impressive feat and deserves acknowledgement.

He or she who places their foot on top of a previously unclimbed mountain will make it into the book of mountaineering history. The first successful attempt of the Matterhorn, however, was like nothing else. It was a triumph of mountaineering – and a tragedy!

In 1786, Doctor Paccard and the peasant Balmat succeeded in being the first to climb Mont Blanc. It was a massive endeavor of enormous importance, not only for the small society in Chamonix at the foot of Mont Blanc, but for the whole alpine region. The ascent encouraged many others to try to repeat what Paccard and Balmat had managed to do. As the years went by, more and more of the Alp summits were conquered: mountaineering was in its golden age, and one by one the seemingly unending number of peaks were climbed. The Matterhorn, on the other hand, remained unclimbed!

By 1860, English alpinists had acquired the majority of successful first ascents in the Alps. England led the industrialization and was prospering. Railways and passenger boats gave Englishmen the opportunity to travel and explore, and for some to live out their interest in sports and physical activity. Many of them were teachers who utilized their long vacations to go to the continent to walk and climb. In small alpine villages at the foot of the mountains, they hired local peasants who, for a modest amount of money, joined the foreign adventurers. To the peasants, mountaineering was as new as it was to the ambitious Englishmen. Together they forged ahead and developed usable techniques and simple, but much needed, equipment.

In England, the young Edward Whymper was ignorant of the endeavors of his fellow countrymen in the Alps, and he knew nothing about mountaineering. It is said that he was bored with life in general and dreamt of traveling and seeing new places. In 1860, a publisher sent the 20-year-old Whymper to the Alps and asked him to return with drawings suitable for the publisher’s books. Whymper left and was strongly taken by the strange landscape he met on his walks in the valleys. The publisher was pleased with his work and sent him back to the Alps the following year. To Whymper, the mountains quickly became a passion, and the sight of the majestic Matterhorn had given him great ambitions.

At this time, just about every mountaineer of the golden age had given up every thought of climbing the Matterhorn. The most skilful said it was impossible, the most daring and adventurous had withdrawn from the challenge, and it was even said that evil spirits lived on the mountain. The Matterhorn was terrifying!

Whymper was undeterred by this. He headed towards the village of Valtournenche on the Italian side of the Matterhorn. At the same time, one of the few other people who still believed the mountain could be climbed, Professor John Tyndall, headed towards the Matterhorn with his guide. They quickly returned, though, as Tyndall’s guide lost his nerve. Simultaneously, Whymper did not succeed in finding men in the town of Breuil who were willing to follow him up on the terrible mountain. At last, however, he did manage to persuade an Italian guide to help him. Together they spent a cold night on the Col du Lion at the foot of the Southwest Ridge, and the following day, they managed to climb only a short way up the mountain before the Italian guide decided to quit. Whymper went home to England, still determined to pursue his dream, and even though he had not yet climbed very high on the mountain, he had become convinced that the Matterhorn could in fact be climbed.

In 1862, Whymper was back. Together with his travel companion, MacDonald, he hired two Swiss guides in Zermatt and began another attempt. But they were soon given up as a storm set in, and the Swiss guides lost their nerve.

Subsequently, Whymper arranged an attempt with Jean-Antoine Carrel – the only mountain guide in town who believed that the Matterhorn could be climbed. As a matter of fact, he had already tried a couple of times, and, being quite arrogant, he thought he was the only one capable of leading such a demanding expedition. Whymper was excited. The first night was spent far above the point where Whymper slept on his first attempt, and he really believed that this time they would make it to the top. But luck was not on their side: Carrel’s guide, Pession, became ill, and this ended the promising expedition. Carrel simply refused to go on without Pession, and, at the same time, he was way too proud to climb alone with Whymper, whom he considered an amateur.

Some days later, MacDonald went home, and Whymper set out for his first solo attempt. The climbing was challenging, and on one occasion he had to jump to reach the next hold far above his head. Whymper knew it was foolish to climb alone; yet he pushed on and got as high as 4100 meters. No one had ever been this high on the Matterhorn. That same evening, he was reminded how dangerous the Matterhorn was with every step potentially leading to a fall. On the descent, he slipped and tumbled some 60 meters down loose rocks before he managed to break his fall at the edge of a cliff. He only just avoided the deadly drop that would have sent him more than a thousand meters down towards the glacier. Using his last reserves of will power, he managed to bring himself to a small plateau where he immediately passed out. After this experience, he went back to Breuil where he once again met Carrel. They agreed to give it a new go, but yet another storm sent them back. By now, Whymper was so convinced that the ascent could be made that he arranged one more attempt with Carrel. On the morning of departure, however, Carrel was nowhere to be found. People said that he had gone hunting.

Whymper was disappointed but still firmly determined. He was going to climb that mountain, and he arranged his sixth attempt with a local peasant, Luc Meynet whom he knew from earlier trips. Some would call this small expedition a success: they reached further than anyone before them. But to Whymper it was another disappointment: so close and yet they had to give up due to Meynet’s lack of skills.

Back in Breuil, Whymper met Carrel, who had not gone hunting but instead joined a strong group with Professor Tyndall, the guide Bennen and another guide. Whymper had to go back to England but felt that he could not leave until he knew whether this group, the strongest on the mountain so far, would make it to the top. He passed the time in the valley anxiously waiting to hear about the result of this promising attempt. At one point, some thought they saw a flag on the top. Whymper waited. In the evening, the group returned, but as Whymper noted, there was nothing victorious in their appearance. They did not make it, but they had been higher than Whymper. They had turned back only 250 meters below the summit, probably due to a power struggle between Bennen and Carrel. Whymper could now go back to England, and no further attempts to climb the Matterhorn were made in 1862.

In the summer of 1863, Whymper went back to Breuil to arrange a new expedition with Carrel, but the weather prevented them from even setting off.

The relationship between Whymper and Carrel was strange. They respected each other, but first and foremost they were rivals. Most other people were still convinced that climbing the Matterhorn was impossible, and, consequently, Whymper and Carrel needed not worry too much about competition to the top. They therefore ventured on other smaller climbing adventures around the Matterhorn. The strange companions came to know each other well. Whymper wondered why Carrel had never tried to climb the Matterhorn alone; he actually suspected Carrel of nourishing the idea of the impossibility of climbing the Matterhorn in order to make his ultimate success all the better.

In 1864, no attempts were made on the Matterhorn. Instead, Whymper climbed other mountains with the French guide Michel Croz, whom he trusted to have the skills necessary to make a serious attempt on the Matterhorn.