18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

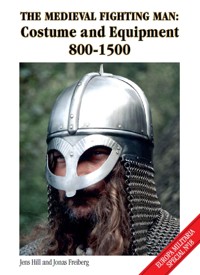

In medieval times an individual often needed to defend his life, his family and his property, and mercenaries earned their living by hiring out their skills, while feudal noblemen regularly mustered their men-at-arms and their subordinate vassals and tenants to provide military service, even to the point of leading them on Crusades to the Holy Land and elsewhere. In the later medieval period the growing cities required their citizens to take up arms as militia in defence of the community during times of external threat. In The Medieval Fighting Man - Europa Militaria Special No 18, meticulous use is made of the sources available to enable the materials, colours and patterns used for reconstructed clothing to represent the 'real thing' as accurately as possible. Fortunately, great numbers of medieval weapons and pieces of armour survived and can now be viewed in displays, and these form the basis of the arms presented in this book. This well-researched guide to the costume and equipment of the Medieval fighting man through the period 800-1500 will be of interest to all collectors, re-enactors, costumiers and military historians, and is fully illustrated with 147 colour photographs.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

THE MEDIEVAL FIGHTING MAN:

Costume and Equipment

800 – 1500

Jens Hill and Jonas Freiberg

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in Germany as

Krieger: Waffen und Rüstungen im Mittelalter 800–1500

By VS-BOOKS, Postfach 20 05 40, 44635 Herne, Germany

© Torsten Verhülsdonk 2013

This edition published in 2015 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2015

English edition © The Crowood Press Ltd 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 010 2

Contents

Preface

Acknowledgements

Viking Warrior – 8th to 9th Century

Carolingian Landowner – Early 9th Century

Scandinavian Trader – 9th to 10th Century

Viking Warrior – Late 10th Century

Norman Miles – 11th to 12th Century

Infantry Serjant – Second Half of 12th Century

Knight Templar of the Third Crusade, 1190

Castellan Knight and Foot-Soldier – Late 12th Century

Knight and Foot-Soldier – 13th to 14th Century

Crossbowman – Mid-13th Century

The Longbowman – First Half of 14th Century

Officer and Foot-Soldier, 1485

The Armed Citizen, 1470–1500

Bibliography

Illustration credits

All pictures were taken by Carl Schulze and Torsten Verhülsdonk with exception of:

Page 3: Image from the Maastrichter Book of Hours, Stowe 17 f.244, British Library, London

Page 4: Picture by Jürgen Howaldt, of the picture stone Hammers I, today displayed in the Bunge open air museum, Gotland, Sweden

Page 10: Mounting of cutout from MS 10066–77 f. 133v, Koninklijke Bibliotheek van België, Brussels, Belgium

Page 15: Stuttgarter Psalter, Cod.bibl.fol.23 158v, Württembergian State Library, Stuttgart

Page 16: Image of the picture stone from Etelhem, now in the Fornsalen Museum Visby, Gotland, Sweden

Page 22: Saxons, Jutes and Angles crossing the sea towards England. Taken from Miscellany of the Life of St Edmund, Bury St Edmunds, England, MS M736 fol.7r, Pierpont Morgan Library New York, USA

Page 27 Bottom picture by Thorsten Piepenbrink

Page 28: Image from Tractatus in Evangelium Johannis, Tours BM MS 0291 f.039

Page 34: Image depicting the capture of Carthage taken from Chroniques de France ou de St Denis, Royal 16 G VI f.441, British Library, London

Page 40: Image from The Westminster Psalter, Royal 2 A XXII f.220r, British Library, London

Page 45 Bottom picture taken by Chavi-Dragon

Page 46: Mounting of cutouts taken from the Winchester Bible, MS M 619v, Pierpont Morgan Library, New York, USA

Page 56: Image of the battle of Roncevaux taken from Chroniques de France ou de St Denis, Royal 16 G VI f.178, British Library, London

Page 68: Image of the siege of Vezelay Abbey taken from Chroniques de France ou de St Denis, Royal 16 G VI f. 328v, British Library, London

Page 73: Bottom image, of a battle for a bridge over river Seine, taken from Chroniques de France ou de St Denis, Royal 20 C VII f.137v, British Library, London

Page 74: Image ‘Bellum/War’, taken from Omne Bonum (Absolucio-Circumcisio), Royal 6 E VI f.183v, British Library, London

Page 80: Image of Hector slaying Patroculus taken from Troy Book, Royal 18 D II f.66v, British Library, London

Page 90: Image of Gideon’s Battle taken from Chronique of Baudouin d’Avennes, Royal 18 E V f.54v, British Library, London

Preface

For the purposes of this book, a ‘fighting man’ is considered to be anyone who had the freedom and the legal right to bear arms, while a ‘man-at-arms’ is a later medieval armoured cavalryman, whether of knightly or lower social status.

In medieval times the individual often needed to defend his life, his family and his property. Mercenaries earned their living by hiring out their skills, while feudal noblemen regularly mustered their men-at-arms and their subordinate vassals and tenants to provide military service, even to the point of leading them on Crusades to the Holy Land and elsewhere. In the later medieval period the growing cities required their citizens to take up arms as militia in defence of the community during times of external threat.

The sources upon which we have drawn for the reconstructions illustrated in this book are many and various, since each usually provides only partial information. The archaeological evidence for medieval material culture may come from single burials or mass graves, from the sewers or wells of castles and cities, less often from known battlefields, and occasionally from chance finds scattered across the countryside. Fortunately, great numbers of later medieval weapons and pieces of armour survived in the armouries of towns and castles, and are now displayed in museums all over the world. This physical evidence may be compared with iconography, and for the earlier centuries we are fortunate in having the illustrated manuscripts that were created in monasteries. The artists who painted these ‘illuminations’ for ancient Biblical and other stories interpreted them in contemporary terms; rich in colour and detail, their work gives us precious information about the clothing and war gear of the artists’ own times. Each chapter of this book begins with an historical image, to show that the reconstructed warrior, armed trader, knight, man-at-arms or soldier is closely based upon historical sources.

The choices of materials, colours and patterns for reconstructed clothing are as close as possible to ‘the real thing’, but inevitably these can only be a matter of interpretation. Much knowledge of the necessary craft skills has been lost over time, and some materials are impossible to source today in appropriate quality. In the case of the early periods especially, original clothing is preserved only in fragments, and the cut of these garments can only be an educated guess based on the available iconography. All of the people portrayed in this book represent as closely as practically possible the appearance of times long past, achieved by studying all available sources, comparing the surviving examples, and experimenting with different craft techniques. This is an ongoing process driven by new documentary or archaeological discoveries, so such reconstructions undergo constant changes. Nevertheless, we have attempted to achieve a level of accuracy that can satisfy critical review by scientific historians.

Acknowledgements

A project such as this would have been impossible without the help of the persons shown in the photographs, and for each subject countless hours of research and reconstruction work were necessary. The authors and publishers wish to record their sincere thanks to all those who were willing to share their knowledge, and to give their time to pose for the photo-shoots. They are, in alphabetical order:

Bryan Betts, Andreas Bichler, Ralf Ebelt, Jonas Freiberg, Jens Hill, Ingo Kammeier, Christoph Ludwicki, Matthias Richter, Oliver Schlegel and the Archaeological Service of the Harz region in Quedlinburg, Gregor Schlögl, Burkhardt Schröder, Olaf Werner and the company I.G. Wolf eV.

Another debt is owed to Die Förderer eV for allowing us to use a harness made by Walter Suckert from the stock of the Landshuter Hochzeit 1475; this was made possible by Karl Heinrich Deutman of the Adlerturm Museum in Dortmund, Germany.

Viking Warrior

8th to 9th Century

Starting in the year AD793 with their raid on Lindisfarne, a monastery located on a small island off the coast of northern Britain, warriors from Scandinavia stepped into the glare of history: ‘The harrying of the heathen miserably destroyed God’s church in Lindisfarne by rapine and slaughter.’ The Anglo-Saxon poet Alcuin lamented that ‘Never before has such terror appeared in Britain as we have now suffered from a pagan race, nor was it thought possible that such an inroad from the sea could be made. Behold the Church of St Cuthbert, spattered with the blood of the priests of God, despoiled of all its ornaments.’ These Norsemen gave a whole epoch the name we use today: the Viking age. The origin of the term ‘Viking’ is itself obscure: whether it derives from the Scandinavian word vig for a bay on the seacoast, or from the word viking to denote the activity of raiding, is still a matter of debate.

During the previous centuries Scandinavia had developed mostly in isolation from the rest of Europe. After the downfall of the Roman Empire in the West in the 5th century a large number of (eventually) Christian kingdoms evolved in the former Roman territories, all sharing a proto-feudal model of society. In some former Roman cities an urban, mercantile culture eventually not only revived but developed. Everywhere Christian monasteries became centres not only of religious life and learning but also, due to the craftsmen and travellers that they attracted, of economic power.

In the far north of Europe, however, where the Romans had never penetrated, the ancient pagan religion survived, as well as the old agrarian structure of society. The typical form of settlement was a pattern of small, mostly autonomous villages spread out over the areas that were practical for agriculture. Central institutions, such as the Church, and the secular kingdom with its feudal structure, were absent from these regions. Jurisdiction beyond the bounds of individual clans lay in the hands of the so-called Thing, a kind of people’s parliament.

Due to the geography of Scandinavia, where mountains divided the farmable and therefore habitable territory into areas of modest size, and due to the consequent absence of central institutions able to organize the construction of interregional road networks, boats and ships became established as the main means of transport from prehistoric times. Unseen by the rest of Europe, a centuries-old tradition of ship-building eventually developed seagoing vessels able to cope with the harsh conditions of the North Sea and Atlantic. In parallel, the Norsemen developed navigational skills that enabled them to determine their position at sea beyond sight of land, making it possible for them to reach any point on the North Sea coastlines directly.

According to the latest research, a prolonged period of high birth rates in territories with only limited agricultural land caused overpopulation in Scandinavia in the late 8th century. The consequence was that armed men set out in search of wealth, and, before long, of new lands for settlement. They sailed across the open sea in their long, narrow, shallow-draught ships, and rowed into bays and up river estuaries; the number of ships bringing men from the North grew year by year, and so did their radius of action. During the first years Viking raids concentrated on the coasts of the British Isles and Frisia, but before long they were attacking all round the shores of the Frankish empire. By the mid-9th century Viking armies had a permanent presence in Britain; soon large numbers of their longships were reaching cities such as Paris and Mainz, located far upstream on the great rivers of the European hinterland, as well as raiding the Mediterranean coasts of Spain and Italy.

The fighting man reconstructed in this chapter stands as a representative for those Norsemen, feared as warriors and admired as seamen throughout the whole of Europe. For a foreigner to encounter this completely equipped Viking warrior at the turn of the 8th and 9th centuries would have been an unlucky meeting.

His relative wealth is shown by the completeness of his gear. The classic round shield and the long spear, combined with a large knife, might be regarded as the ‘basic kit’ of a Viking warrior – the signs of a free, weapon-bearing man. For close-quarter fighting an axe (thought of today as the iconic weapon of the Vikings) might be carried; the long sword, slung in a scabbard at his left side, was a weapon reserved only for the wealthy, especially in the early phase of the Viking era. According to contemporary sources the amount of money needed to purchase such a weapon would have bought a medium-sized farmstead. Nevertheless, this precious object is outpriced by two other parts of his gear that immediately catch the eye. While the warrior of average means would have been protected by – at best – body armour made of several layers of cloth or leather, and a reinforced leather cap, this man is wearing a ring-mail shirt and a helmet made of iron.

The ring-mail shirt

Although the manufacture of mail armour in Europe predated Viking times by more than a thousand years, two main factors limited its use in 8th/9th-century Scandinavia. One was the simple cost of the material needed – more than 10kg (22lb) of good-quality iron. The other was the extremely time-consuming process of manufacture by skilled craftsmen, which made such protection very expensive. The raw material, normally traded in ingots, was first forged into thin rods, which then had to be drawn out into thinner wire during several successive steps of the process. In the next stage this wire had to be coiled around a metal-rod former into a spiral; dividing this spiral into segments by a lengthways cut along the former produced the single ‘raw’ open rings. These then had to be finished individually by flattening and overlapping each end, and punching holes through these to take the rivets that would be hammered in as the last step, after each ring had been interwoven with four others. More than 25,000 rings went into the manufacture of the mail shirt illustrated here; this hringserkr or brynja is made of a strong and flexible mesh, protecting the wearer’s body against cutting blades and some impacts from thrusting points.

The length of this shirt is, according to the sources, typical for this early era. Longer shirts, reaching to the knee and below, equipped with long sleeves and worn in conjunction with mail mittens and stocking-like mail leg armour, are not found in the sources for this period. The only other use for mail was attached to the rim of the helmet, in a curtain to protect the wearer’s neck and, sometimes, his lower face.

Since the ring-mail shirt only gives protection against cuts and, to a lesser extent, against thrusts, our warrior is wearing a padded jacket beneath it. Like the protective garments worn alone by less wealthy men, made from several layers of cloth or leather, this undergarment was meant to reduce the ‘blunt trauma’ produced by the sheer force of blows. Called in later centuries a gambeson, it was characterized by relatively soft padding (perhaps of horsehair, fleece or felt) sewn in between two layers of cloth.

The weight and ballistic qualities of this spear make it improbable, though not impossible, that such weapons were thrown; they were for thrusting or cutting in face-to-face combat. Various sources show shields painted in halved or quartered patterns.

The helmet

Like the ring-mail shirt, and for the same reasons, our warrior’s helmet had a worth far beyond the simple cost of the iron needed to make it. The example illustrated is based upon a helmet unearthed from a grave in the Norwegian town of Gjermundbu, together with fragments of a mail shirt and other equipment. Finding remnants of only one of these items in a grave is quite remarkable; finding both on a single site may be called unique. The ‘goggle-like’ protection for the upper face is typical for one group of Scandinavian helmets, of which unmistakable fragments have been found in several other places. Earlier complete helmets of very similar types have been excavated from graves near the town of Vendel in Uppland, southern Sweden; these may date to as early as the mid-6th century, thus confirming a long Scandinavian design tradition.

This portrait gives a good impression of the details of the Gjermundbu-type helmet with its attached mail curtain. In other contemporary societies the trimmed full beard and long hair might be a sign of high status, with only the wealthy having the spare time to devote to such indulgence, but contemporary sources tell us that when they had the leisure the Vikings took care over dressing their hair and bathing.

The shield and weapons

The shield carried by our warrior, with a diameter of approximately 1m (40in) corresponds quite well to the preserved shields found in the late 9th-century Gokstad ship. That famous find included no fewer than sixty-four flat, circular shields made from limewood planks, with the outer edge bound with a sewnon strip of rawhide; since the wood was only about 5mm (0.2in) thick, the shield was light enough to be manipulated easily in combat. The hemispherical iron boss in the centre covers a hole that accomodates the user’s hand when he holds the shield by its bar-like grip across the centre of the interior. While the Gokstad shields were painted in either yellow and black directly on the wooden planks, this reconstruction is covered by a layer of cloth or leather, giving additional stability. The battle-scars on the boss and face show that this shield has already been carried into several skirmishes.

The interior of the shield has a central bar grip, and also a shoulder strap for slinging it.

The spear, with an ash-wood shaft approximately 2.5m (8ft 2in) long, has a head of a leaf shape matching many finds in and beyond Scandinavia. Its broad blade makes it a general-purpose weapon, suitable both for hunting large game and, especially, for fighting unarmoured opponents, and its weight makes it practical for both thrusting and cutting. An experienced warrior could use this weapon single-handed, with the shield held in the other hand. Slimmer spears with narrower heads were used for throwing.

The sword in our reconstruction has a double-edged blade about 90cm (35in) long, and would have a shallow groove or ‘fuller’ down each side; this is a type quite common in the Viking era. The most desirable blades of all, often pattern-welded, were imported from the Frankish kingdoms, and would be fitted with more or less ornate hilts by Viking craftsmen. For the wealthy they were sometimes decorated with inlaid gold, silver, copper, or black niello, and fitted with metal, ivory, bone or horn grips. However, the swords carried by most everyday warriors were undecorated apart from the characteristic shape of the pommel, and were furnished in simple wood and leather. Scabbards were made of thin wood covered with leather, and often lined with waxed or oiled material or natural sheepskin to protect the steel against rust. Here the throat of the scabbard, its suspension loop, and the chape reinforcing its tip are made of bronze. Other than in central Europe the sword was not carried by an elaborate suspension formed from several laces, but simply looped onto a shoulder strap (baldric) fastened by a buckle in the front.

The find-site of a sword would not reveal much about its origin, as warriors and traders travelled very widely, but comparing some details with the distribution of specific designs throughout Europe makes it possible to give a rough classification. This particular type of guard can be found in Denmark, the Danelaw (the settlement area of the Norsemen in northern and eastern England), and in the region of the Baltic Sea. The elaborate decoration is achieved by the inlaid ‘damascene’ technique, with strips of silver or copper alloy hammered into grooves filed in the steel. Sometimes the whole surface of the hilt was covered during this process, but most of the swords that have been found lack such decoration.

The bronze chape both decorates the tip of the sword scabbard and protects it from damage. The characteristic Scandinavian decorative style for this period showed stylized animal figures, real or mythological, interwoven in very complex patterns. Also visible here is the sewn-on tablet-woven braid, made from dyed woollen yarn, that decorates the hem of the tunic.

Clothing

Although we have already pointed out that the quality of his war gear identifies our Viking as a wealthy man, his basic clothing is mostly governed by practical needs – including those of somebody spending weeks at a time living on a small, usually undecked ship. His straight-cut tunic, reaching to the knee and with long sleeves, is made from a densely woven woollen fabric. This is not dyed, but is woven from yarn of two natural colours that allows the creation of a rectangular pattern during the weaving. However, the edges of the tunic are decorated with strips of patterned, tablet-woven braid made from dyed yarns. His trousers are closely fitting, made from wool with a felted surface that makes it to some degree wind-and water-repellent. On his feet are a pair of simple, undecorated leather ‘turn-shoes’.

His leather belt is fastened with a decorated copper-alloy buckle and has a matching decorated strap-end, and supports at his back a slung pouch for small necessities. The contents of such pouches naturally varied. Besides such obviously useful items as a ‘lighter’ (consisting of an iron fire-striker, flint stone, and a supply of dry tinder), they might also contain a ‘grooming set’ (tweezers, nail-scraper, perhaps a small pair of scissors), a comb made from antler or bone, and even a sewing kit. Perhaps belying their popular image today, contemporary eyewitnesses reported that the Norsemen were vain about their appearance.

The capture of prisoners for sale was one of the Vikings’ greatest sources of income. Spain, which was under Arab rule at this period, was a major market for slaves, where customers were willing to pay high prices for sturdy European men and women.

A skirmish outside the earth and timber ramparts of a major stronghold of the Viking period, perhaps in Russia. The tree trunks laid vertically on the face of the earth bank made it difficult for attackers to climb, under the spears and arrows of defenders on the battlements.