28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

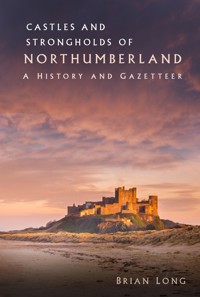

Mercedes-Benz 'Fintail' Models charts the development of the W110, W111 and W112 'Fintail' (or 'Heckflosse') series, the line that helped revive the Mercedes-Benz brand in the post-war years. With a unique combination of exceptional engineering and a timeless beauty, even the most basic of these vehicles has a charm that is difficult to find in the majority of cars today. After outlining the company's history, the book looks at the development of the first of the 'Fintail' models - the W111- and its launch at the 1959 Frankfurt Show. It also looks at the closely related 1.9 litre W110 and 3.0 litre W112 models, with the vehicles sold in the German, US and UK markets covered in detail.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 286

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

MERCEDES-BENZ‘FINTAIL’ MODELS

THE W110, W111 AND W112 SERIES

MERCEDES-BENZ‘FINTAIL’ MODELS

THE W110, W111 AND W112 SERIES

Brian Long

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2014 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2014

© Brian Long 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 604 8

Photographic Acknowledgements All images have been sourced from the Mercedes-Benz factory archives, or come from the author’s collection.

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction

The Family Tree

Chapter 1 – History of the Brand

Chapter 2 – Birth of the W111 Series

Chapter 3 – The First ‘Heckflosse’ Cars

Chapter 4 – Augmentation

Chapter 5 – The ‘Fintail’ Models In Competition

Chapter 6 – Mid-life Crisis

Chapter 7 – A ‘Fintail’ Swansong

Appendix I – The W111 & W112 Model Lines

Appendix II – W110, W111 & W112 Production Figures

Index

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

As I’ve said before, it’s a real pleasure working with Daimler AG, not just because the staff are particularly helpful and proud of the Mercedes-Benz name in today’s context, but also because they’re just as proud of the firm’s heritage. Some car companies (one in Italy springs straight to mind in particular!) believe there is no value in promoting the past – they cannot see how a book on vehicles made decades before can help sell something built today.

Enthusiasm breeds enthusiasm – a point so often lost in the modern era, when answering to the short-term greed of shareholders seems more important than the long-term well-being of a brand that its founders worked tirelessly to develop. These books record that immense effort, preserving history, and fire the passion of those who cannot – for whatever reason – obtain the cars in question. Even without a machine on the driveway, there are still many people supporting brands worldwide, and Daimler AG appreciates this fact.

Books also give younger generations a dream to aspire to. As Sir William Lyons once said on hearing a dealer complaining that schoolboys were cluttering the stand and taking all the catalogues at a motor show with little or no chance of them buying a vehicle: ‘Let them take the brochures. Let them sit in the cars. They may not be a customer today, but get them hooked on Jaguar now, and there’s more chance of them being a customer tomorrow.’

As with the author’s earlier books, help came from many quarters during this project. I would particularly like to record my sincere appreciation for the services of Gerhard Heidbrink, a sterling ally, plus Dennis Heck, Dr Hans Spross and Maria Feifel at Daimler AG in Stuttgart, as well as their colleagues from many years earlier – Max Gerrit von Pein and Dr Harry Niemann. Many thanks also to Diane Vatchev of Mercedes-Benz USA for her continuous support, and for once again coming to the rescue on the American side of the story.

Although there are many others that have helped and supported me with this book, special mention should be made of Elif Yilmaz at EVO Eitel & Volland GmbH, who look after older technical publications for the Mercedes-Benz Classic Collection, Kenichi Kobayashi at Miki Press, Rob Halloway at Mercedes-Benz UK, and Peter Patrone, Robert Moran and Benjamin Benson at the head office in the US.

I sincerely hope that readers enjoy this book as much as I enjoyed putting it all together. As this may well be the last car book I write, if it creates one new enthusiast, or broadens the range of interest of existing Mercedes-Benz fans, I shall be a happy man…

BRIAN LONGChiba City, Japan

A‘Fintail’ Cabriolet.

INTRODUCTION

The Mercedes-Benz brand had enjoyed an unrivalled reputation for high quality and aesthetic appeal before the Second World War. Probably more than any other series, it was the ‘Fintail’ (or ‘Heckflosse’) line that helped revive that reputation in the post-war years, the various models sporting a unique combination of exceptional engineering and a timeless beauty – even the most basic vehicles have a charm that is difficult to find in the majority of cars today.

After outlining the company’s history, the book will look into the development of the first of the ‘Fintail’ models – the W111 – and track the 2.2-litre car’s evolution following its launch at the 1959 Frankfurt Show, including things like prices, options, standard colour schemes and major production changes. The story will also take in the closely related 1.9-litre W110 and 3.0-litre W112 models, with the vehicles sold in the German, US and UK markets covered in detail, as well as the odd contemporary press comment.

The main achievements of the ‘Fintail’ models in racing and rallying are then appraised before looking at the new engine lines for the production models and how this fitted into the overall scheme of things at Mercedes. With the W110 and W112 gone by the end of the sixties, the final chapter covers the last of the W111s, which included a new V8 model – every bit as desirable now as it was over four decades ago. To finish off, there are detailed appendices covering body and engine options, and production figures.

Incidentally, the vast majority of illustrations have been sourced from the factory in Stuttgart, augmented by contemporary advertising from the author’s collection, in order to provide those looking for authenticity with an ideal resource for research before restoration, or for detailing existing show cars.

A 4-cylinder saloon.

A 6-cylinder saloon.

A ‘Fintail’ Coupe.

The Family Tree

The use of model numbers, which seem to change depending on the source material (internal use and catalogue designations, which duly get mixed up with the passage of time) makes tracking ‘Fintail’ development quite difficult at first sight. This series of family trees, starting with the equivalent predecessor (shown in blue) and ending with a car’s ultimate direct replacement (shown in red) in a particularly confusing era, should hopefully simplify things a little:

The 6-Cylinder Saloons

CHAPTER ONE

HISTORY OF THE BRAND

The name of Mercedes-Benz, as well as the three-pointed star trademark that goes with it, both physically and mentally, is recognized all over the world as a symbol of prestige, exemplifying the highest levels of German quality and engineering. Indeed, when Janis Joplin made an appeal in 1970 to the ‘man upstairs’ for a colour TV and a car, she didn’t ask for something from her US homeland, and certainly not Japan, she specifically asked for a Mercedes-Benz. It’s therefore worthwhile reflecting on the history of the brand, and what made it so renowned, before moving onto the book’s main subject – the so-called ‘Fintail’ cars.

The Mercedes-Benz story begins with two pioneers of the motor industry – Gottlieb Daimler and Carl Benz. Somewhat surprisingly, despite the fact that both were German-born (and therefore obviously German speakers) and both were leading lights in the fledgling automotive trade, based less than 60 miles (100km) away from each other, they never actually met. Nonetheless, the coming together of the two companies they founded is what concerns us here, with the Daimler-Benz business using the Mercedes-Benz badge on the majority of its road vehicles from the late 1920s onwards.

BIRTH OF THE DAIMLER MARQUE

Gottlieb Daimler with his first wife, Emma.

Gottlieb Daimler was born in Schorndorf, a stone’s throw to the east of Stuttgart, on 17 March 1834. Daimler did not come from an engineering background (in fact his father was a baker), but it was obvious from an early age that this was to be Daimler’s destiny, for as well as learning Latin, he attended technical drawing school as a young boy.

Although he started his apprenticeship with a local gunsmith, as soon as his four years were up he began studying engineering in greater depth, augmenting his academic work with practical experience gained in the field in France and Britain.

On settling back in Germany, Daimler moved around for a while, although his appointment as Technical Director of the Gasmotoren-Fabrik Deutz AG (founded by Nikolaus August Otto, the father of the four-stroke, ‘Otto-cycle’ engine) in 1872 was an important step in his career, with Wilhelm Maybach (1846–1929), whom he had first met as a colleague in 1864, already present as his right-hand man.

However, a rift between Daimler and the Cologne-based manufacturer grew in time, with Daimler and Maybach wanting to develop faster-running petrol engines that could release more power. Ultimately, in 1882, Gottlieb Daimler decided to go it alone and opened a small workshop at the back of his villa in Cannstatt, on the out-skirts of Stuttgart, with Maybach working alongside him to help nurture this new technology.

A 2hp Daimler V-twin engine of 1889 vintage.

A number of single-cylinder, air-cooled petrol engines were duly designed and built, one being used to power the world’s first motorcycle in 1885. There was also a four-wheeled horseless carriage, actually produced for Daimler’s wife as a birthday present, which made its initial runs during the autumn of 1886. Within a short space of time, the engines were finding various applications on land, rails, water, and even in the air. After building a second car in 1889, this time powered by a water-cooled V-twin, it was obvious that Daimler and Maybach were moving in the right direction, and investors soon started knocking on the door of the large new factory in Cannstatt.

The workforce of the Daimler Motoren Gesellschaft (DMG) pictured in 1893. Note the stationary engine in the centre of the image – automobiles were still a long way from being a staple product for the Stuttgart company.

A Daimler Phönix pictured in Germany at the turn of the twentieth century.

The Daimler Motoren Gesellschaft (DMG) was registered on 28 November 1890, its purpose being to manufacture and market Daimler engines and related products. In addition, there was a great deal of licensing activity in this new and exciting field of engineering, with Panhard & Levassor of France being one of the first to sign up. There was also a company founded in America bearing Daimler’s name (with William Steinway of Steinway piano fame behind it), and another in England, thanks to the business dealings of Frederick Simms and Harry Lawson.

As so often happens once investors get involved, though, profits start to dominate decisions, and the desire to experiment usually has to be tempered with the sale of products to satisfy short-term requirements. Maybach was forced to leave the Cannstatt company due to a clash of policy, and Daimler’s health was failing – a situation not helped by the internal conflict with members of the DMG Board. Perhaps not surprisingly, Daimler ultimately resigned from the company he had founded in October 1894.

Daimler and Maybach duly joined forces again (they had remained close friends even after the latter left DMG), this time bringing Daimler’s son, Paul, into the fold, and between them they designed a 2.1-litre 4-cylinder engine equipped with Maybach’s innovative spray-nozzle carburettor. Known as the Phönix, it was a landmark unit, and, following some political manoeuvring from Frederick Simms, the pair was asked to return to the Daimler Motoren Gesellschaft on new, more favourable terms.

Gottlieb Daimler died on 6 March 1900, although Wilhelm Maybach continued his work before becoming heavily involved with aero-engine production for the famous Zeppelin airship concern. After the Great War, Maybach marketed a short-lived series of luxury cars under his own name, with the brand being revived recently for a Mercedes-Benz flagship saloon.

GENESIS OF THE BENZ BRAND

Carl Benz was born in Mühlberg on 25 November 1844. The son of a train driver, after leaving school, he went to the Karlsruhe Polytechnic to study mechanical engineering, and after graduating duly moved around a number of firms, gaining practical experience in a wide range of fields, from building locomotives to designing machinery and even iron bridges. Joining forces with August Ritter, Benz established his own engineering shop in Mannheim, about 55 miles (90km) north of Stuttgart, in August 1871, but the partnership was short-lived, with Benz ultimately buying Ritter out. The small workshop was not a success, though, and Benz turned his attention to developing two-stroke engines (there were too many patents already registered against four-stroke powerplants) in the second half of 1877, with the first unit running successfully two years later.

By late 1882, the Benz engine had attracted investors, and Gasmotorenfabrik Mannheim was established, although Benz left the company within a few months of starting it as the shareholders tried to influence things too much. For instance, Benz wanted to produce a motor vehicle, but a quick financial return on supplying engines was favoured by the majority of people. Having put up production facilities as his stake in the business, Carl Benz was left no option but to start again from scratch.

Carl Benz in his younger days. Unlike Daimler, who died when motoring was still in its infancy, Benz was fortunate to live longe nough to witness it evolve from a sport for the well-heeled into an essential part of daily life.

Luckily, on 1 October 1883, Max Rose and Friedrich Esslinger came to Benz’s aid in helping to form a new company, Benz & Co. Rheinische Gasmotorenfabrik, Mannheim. Not long after, many of the patents applying to the four-stroke engine were declared null and void, allowing Benz to start developing a new, fast-running powerplant based on the Otto-cycle. By 29 January 1886, a patent had been filed on the world’s first, purpose-built vehicle to be powered by a petrol engine – the three-wheeled Benz Patent Motorwagon. Refinements were made, and the car was duly put into series production, the ‘Model 3’ version thereby providing the foundation stone for the automotive industry.

Ironically, in the spring of 1890, despite Benz & Co. being Germany’s second largest engine manufacturer, Carl Benz once again found himself alone in business. New partners were promptly found, however, and Benz continued to innovate, with four-wheeled cars being produced, new steering systems designed, and the horizontally opposed (boxer) engine being developed, amongst other things.

The four-wheeled Velo, introduced in April 1894, was a huge commercial success by the standards of the day (around 1, 200 were built), allowing a new company, Benz & Cie. AG, to be registered in May 1899. However, blinded by the company’s bid to try to compete with a flood of cheaper machines built in France, Benz became dis-illusioned with the people running the firm and resigned in January 1903.

Carl Benz’s three daughters, Thilde, Ellen and Klara, pictured in a Benz Patent – one of the world’s earliest road cars. Some examples of the Patent model were fitted with wooden wheels.

A NEW CENTURY, A NEW AGE

Daimler and Benz were still rivals at the turn of the century, the companies bearing their names fighting in the showrooms graced by the rich and famous, and in the long-distance races and hillclimbs of Europe.

As it happens, the competition link led to the birth of the Mercedes brand. Shortly after Gottlieb Daimler passed away, Emil Jellinek (an Austrian businessman, who, among other things, sold Daimlers to wealthy clients in the south of France) entered a couple of Daimlers in the Nice–La Turbie hillclimb using his pseudonym ‘Mercédès’ – the name of his daughter.

Following the fatal accident of one of the drivers, Jellinek proposed a number of changes that would not only improve safety, but also enhance the sporting nature of the vehicles to satisfy the needs of his customers. He requested a reduction in weight, a lower body, and a longer wheelbase in order to cope with the greater power outputs he outlined. Jellinek promised to purchase a large number of these vehicles in return for distribution rights in France, Belgium, the Austro-Hungarian Empire and America, but also requested that they carry the ‘Mercédès’ badge.

An 1897 works photo, with a Benz Vis-a-Vis on the left and a light weight Velo model on the right. August Horch, of Horch and Audi fame, can be seen seated in the middle of the front row, as he was one of the Benz management at the time.

A deal was struck on 2 April 1900, and Wilhelm Maybach set about designing the first Mercédès in conjunction with Paul Daimler without delay. By the end of the year, Jellinek had taken delivery of the first of the line – a racing car that ultimately provided the foundation stone for the modern automobile, with a low-slung, pressed steel chassis frame playing host to a 5.9-litre, 35bhp engine cooled by a honeycomb radiator, and a gate for the gearchange.

The Mercédès was raced with a great deal of success, and many variations were produced for regular road use, from an 8/11bhp version all the way up to a 9.2-litre 60bhp model. The Mercédès (the name being registered as a trademark by DMG in 1902), set the standard for the day in the high-class car market, and was built under licence by numerous manufacturers.

Luckily, the DMG Board had made preparations for expansion in advance of its commercial success, buying a large piece of land in Untertürkheim on the eastern edge of Stuttgart in August 1900. The factory there began operations at the end of 1903 and duly become the spiritual home of Mercedes-Benz.

Six-cylinder engines followed in 1906, and there was a limited run of Knight sleeve-valve models just before the First World War. Meanwhile, the famous three-pointed star had been registered as a trademark, with approval eventually coming in February 1911. The three arms within the three-pointed star represent the land, sea and air, and indeed each has been conquered in the Stuttgart company’s own inimitable way over the years; the outer ring was added in 1921.

Shortly after the Great War, when the conflict had, if nothing else, allowed technology, metallurgy and production techniques to make great advances, the first supercharged Mercédès made its debut. And on 30 April 1923, Ferdinand Porsche was drafted in from Austro-Daimler to replace Paul Daimler as Chief Engineer, bringing overhead camshafts and front-wheel brakes to the marque in a series of exceptionally elegant supercharged models.

Camille Jenatzy’s Mercédès in the 1903 Paris–Madrid race.

An American advert from 1906, when William Steinway of piano manufacturing fame (and actually of German heritage) was building Mercédès cars under licence in the States. The venture was short-lived, but interesting nonetheless from a social history point of view.

A Mercédès 28/50hp model built for Japan’s Emperor Yoshihito in 1912. As it happens, Yoshihito was a huge fan of all things German, and even styled his moustache after that of Kaiser Wilhelm.

Mercédès advertising from 1917.

In the meantime, Benz & Cie. AG came to the fore, modernizing its range via conventional 2-and 4-cylinder cars designed by Marius Barbarou. The move towards reasonably priced machines allowed the Benz business to clock up world-leading sales of around 600 units a year at the turn of the century, but the policy was out of step with that of Carl Benz himself. As mentioned before, he gave up his post as Chief Engineer, although he did remain on the Supervisory Board until his death on 4 April 1929.

Benz advertising from 1918.

While all this political manoeuvring was going on, Carl Benz had formed a new company with his son Eugen on 9 June 1906, called C. Benz Söhne. By 1908, it had turned to car production after demand for the gas engines they were building fell off. This particular business, based in Ladenburg, to the east of Mannheim, was duly handed over to Eugen and his younger brother, Richard, in 1912. However, with the problems associated with the German economy following the First World War, the firm officially stopped building cars in 1923.

Benz & Cie. AG continued down its safe path with its vehicle line-up, with a racing programme, and diesel engine and aero-engine development going on in the background. The Benz badge gained its laurel wreath in the summer of 1909, and a takeover of Süddeutsche Automobilfabrik Gaggenau GmbH not long after provided Benz with a ready-made line of commercial vehicles.

Meanwhile, Hans Nibel had been put in charge of car design from 1910. Interestingly, Nibel’s own love of racing (he’d been involved with the machine that formed the basis for the ‘Blitzen Benz’ record breaker) spawned a number of competition cars, and the Benz marque duly found favour with a wealthy clientele. One of the most ardent supporters of the brand was Prince Heinrich of Prussia – the brother of Kaiser Wilhelm II.

A 24/40hp Benz Landaulette from 1907.

Benz introduced its first 6-cylinder powerplant in 1914. This was actually an aero-engine, but the company stuck almost exclusively to straight-sixes for its road cars following the First World War. During the war years, Benz had produced some magnificent aero-engines, including 4-valve-per-cylinder units and a V12 prototype. It also emerged from the conflict as a leading light in the field of diesel technology.

THE MERGER OF TWO GREAT HOUSES

Following the end of the First World War, Germany suffered greatly at the hands of hyperinflation. Such conditions are naturally far from ideal for manufacturers of expensive goods, and with Deutsche Bank holding a huge amount of shares in both the Daimler Motoren Gesellschaft and Benz & Cie. AG, it was decided that a syndicate be formed in order to save production costs. An agreement of mutual interest was duly signed on 1 May 1924, with a full merger and the birth of Daimler-Benz AG taking place on 28 June 1926.

Although the company was known as Daimler-Benz, the cars were marketed using the Mercedes-Benz name, with Mercedes officially losing the accents along the way. Only two Benz models made it into the Mercedes-Benz passenger car programme, and both were gone by 1927. A new badge, combining the Mercedes-Benz name, Benz laurels and the familiar three-pointed star had been registered soon after the merger.

There were straight-eights from October 1928, and following the departure of Ferdinand Porsche at the end of the year, Hans Nibel took over sole responsibility as the company’s Chief Engineer; the pair had been sharing the post since the merger.

Despite the difficult financial climate left in the wake of the Wall Street Crash, the marque entered the mid-1930s with some magnificent creations, with the SS and SSK giving way to the 500K and 540K. By this time the company was producing a range of vehicles that went from modest 1.3-litre saloons, with its NA four at the rear, all the way up to 7.7-litre supercharged eights with their glamorous, coachbuilt bodies.

Benz production in 1910.

The ‘Grand Hall’ at the Benz works in Mannheim during the early stages of the First World War.

The year 1934 witnessed the debut of the first of the Silver Arrows – the ultra-modern W25 Grand Prix car. This was followed by a string of successful models, which, combined with the might of the Auto Union team, put Germany at the forefront of the motorsport scene until the outbreak of the Second World War. Record-breakers were also built, based on the GP cars, and brought the new Autobahn (motor-way) network into use in a rather unexpected fashion – the straight, level roads being perfect for the challenge to find the fastest man on Earth.

Following Hans Nibel’s death in 1934, Max Sailer took over as the head of design and R&D. Sailer had been associated with the Stuttgart marque for decades, most visibly as a racing driver of note in the vintage era. During Sailer’s watch, products as diverse as the 540K, the 170V and 170H, and the 260D (the world’s first diesel series-production passenger car) were released. The factory also built the first batch of VW30 test vehicles during the spring of 1937 – the ancestors of the Volkswagen Beetle.

Then, of course, 1939 brought with it conflict, first in Europe, and then on a global scale. Virtually all the historic Untertürkheim factory was destroyed during successive Allied bombing runs in November 1943 and September 1944. Other plants were either destroyed or badly damaged, too, making it difficult for Daimler-Benz to bounce back once the hostilities came to an end in 1945.

THE IMMEDIATE POST-WAR YEARS

Fritz Nallinger had been appointed Chief Engineer in 1940, taking over from Max Sailer. Having been in charge of commercial vehicle development since May 1935, he was already a trusted and highly experienced member of the Daimler-Benz team, and therefore an ideal candidate for the job.

Like so many manufacturers, Daimler-Benz warmed over some of its pre-war designs as part of the rebuilding process, releasing its first post-war car (ignoring utilitarian versions and commercial vehicles) in July 1947 – the bread-and-butter 1.7-litre 170V four-door sedan. By October that year, 1, 000 had been built, but commercials and repair work dominated the scene in Stuttgart as the transition from military to civilian production took place.

A domestic advert proclaiming the merger of two of the greatest names in the German car industry, if not the world.

Research and development work recommenced in the middle of 1948. Soon after, the Unimog was unveiled, and car production reached 1, 000 units a month. Granted, it was still less than half the figure posted in the years leading up to the war, but for Dr Wilhelm Haspel, the company’s Chairman, it must have seemed like a definite and most welcome sign of imminent recovery.

Two new 170-series variants (the 170S and 170D) joined the line-up in May 1949, and production continued until 1955, by which time the 180 had been introduced as a stablemate. The 170V and 170D were revised in June 1950, receiving, among other things, more powerful engines. Their popularity helped Daimler-Benz breeze towards a landmark figure of 50, 000 post-war passenger cars built in October that same year.

Safety considerations were already starting to play an important role in vehicle development at Daimler-Benz. Karl Wilfert (in charge of body development at the Sindelfingen plant) filed a patent for a safety door lock in 1949, and Bela Barenyi came up with the passenger safety cell in 1951. In principle, both of these inventions are still in use to this day.

A 12/55hp Mercedes-Benz Type 320 Cabriolet D from 1928. The Teutonic styling always managed to combine practicality and elegance.

Racing hero Rudolf Caracciola pictured with a Type 460K ‘Nürburg’ Cabriolet C in 1930. Designed by Ferdinand Porsche and updated by Hans Nibel, it was the first Daimler-Benz car to feature an 8-cylinder engine.

The supercharged 500K Special Roadster from the mid-1930s.

Start of the 1938 Tripoli Grand Prix, with the Mercedes-Benz drivers quickly pulling away from the Maseratis, and the Alfa Romeo and Delahaye just behind the line of W154s. Another Alfa had started on the front row, but the Silver Arrows finished in a one-two-three formation, a long way ahead of the rest of the field.

1951 also witnessed the revival of 6-cylinder engines with the launch of the 2.2-litre 220 series (W187) and the 3-litre 300 (W186 II) models unveiled in Frankfurt in the latter half of April. The 300 quickly picked up the nickname‘Adenauer’, as the German Chancellor, Konrad Adenauer, was a staunch supporter of the model, and was rarely seen in public without one. The sporting two-door 300S (W188) made its debut later in the year at the Paris Salon.

The 170 series was updated again in 1952, with new models augmenting revised ones, but the debut of the 300SL sports-racer was perhaps the most telling sign that Daimler-Benz was back, its reputation being restored in the showrooms and on the track. A convincing win at Le Mans was followed by a deal with Max Hoffman, which secured a good sales outlet for Mercedes-Benz cars in America. Hoffman also handled Porsche, VW, Alfa Romeo and Jaguar imports for the US.

September 1953 marked the arrival of the slab-sided ‘Ponton’ series, giving the styling cue for a whole new generation of Mercedes-Benz models. It was launched in 1.8-litre 4-cylinder guise (W120), but a 2.2-litre 6-cylinder version (W180) had joined the line-up by the following spring as a replacement for the W187 model.

On the sporting front, 300SL and 190SL proto-types made their debut at a show in New York in early 1954, in the same year as the W196 Grand Prix car hit the tracks. As expected, it was a winner straight out of the box, and continued to dominate wherever it went in the following season, too. Domination with the 300SLR in the 1955 Mille Miglia was sadly over-shadowed by the Le Mans disaster, where many spectators died following a freak accident, and Mercedes withdrew from racing soon after. A second magnificent era in motorsport had come to an end.

In the meantime, Daimler-Benz of North America Inc. was founded in Delaware on 7 April 1955 to handle US imports. With so many new models coming in 1956, such as the 190, 219 and 220S, the timing couldn’t have been better. Interestingly, though, in April 1957 (the month after the 300SL Roadster made its debut), a deal was struck with the Curtiss-Wright concern, and the Studebaker-Packard Corporation took on responsibility for the sales of Mercedes-Benz cars and diesel engines in the States. A subsidiary of Studebaker-Packard called Mercedes-Benz Sales Inc. (MBS) was duly formed in August 1958.

The Sindelfingen works in 1950, with the pre-war 170 series resurrected to get production rolling again after the conflict. The Sindelfingen site had originally been purchased during the Great War era to allow the building of aircraft and aero-engines.

A US advert for the new ‘Ponton’ model. This line of vehicles, which made its debut in 1953, had modern styling and these were the first Mercedes-Benz models to feature unit body construction.

The Mercedes-Benz stand at the 1954 Earls Court Show in England.

American advertising for the 1958 model year 300d (W189). Note that US distribution rights had been awarded to the Studebaker-Packard Corporation in the spring of 1957.

Back in Germany, the passenger car range was over-hauled in time for the 1958 model year, and during that sales season, power-assisted steering and seat-belts became an option long before the latter became a legal requirement. Other safety-minded introductions included a new wedge-pin door lock, and a proper crash test programme, which began in earnest at the tail end of 1959.

September 1958 brought with it a new fuel-injected 220SE (W128) model, and air conditioning became available on the 300-series three months later. Success in the field of long-distance rallying took the place of victories on the track, while success in the showrooms was easy to quantify, with annual production averaging around 100, 000 units a year by this time, plus around 55, 000 commercial vehicles.

Many companies talk of having pedigree, but it is fair to say that few can match the bloodlines behind the Mercedes-Benz brand.

The Mercedes-Benz Distributors of California Inc. showrooms on Hollywood’s Sunset Boulevard, pictured here in 1955. The 300SL sports cars on the right helped revive images of the Silver Arrows racers, bringing a huge amount of Stateside publicity for the Stuttgart concern.

A Type 190Db (W121 DII) ‘Ponton’ model, built from June 1959 to September 1961. This was a facelifted model with a lower, wider grille.

CHAPTER TWO

BIRTH OF THE W111 SERIES

With the dawn of unit-construction bodies, the cost of tooling had to be considered carefully, meaning a longer production run to recoup hard-earned investment capital. In turn, this meant getting the design – and the mechanical specification, for that matter – right first time, balancing the equation by going for something that would be recognizable as fashionable without being a slave to fashion. It had to be striking enough to be noticed without being too showy, as per the Teutonic custom. In an era of great change in automotive design, creating such a car was hardly the easiest of tasks.

Throughout Mercedes-Benz history, other than a few trailblazing oddities like the 130 (W23), we have always seen steady evolution in the company’s passenger car design, such as the move from the W153 to the W187. In reality, it didn’t take that much imagination to link the styling cues of the ‘Ponton’ body to that of the ‘Adenauer’ 300 models either.

However, times and tastes were changing fast in the 1950s, and if we compare the Citroën DS, for instance, which had been introduced at the 1955 Paris Salon, with the contemporary Mercedes W136 VIII (the last of the 170 series cars, built up until the autumn of 1955), or even the preferred transport of the German Chancellor at the time, the rate of progress was easy to see.

Initial thoughts on the replacement for the ‘Ponton’ were put together in the spring of 1956, when Professor Fritz Nallinger, the firm’s Technical Director, called a meeting with Karl Wilfert (the head of body engineering at the Sindelfingen plant, having joined Daimler-Benz in 1929), Rudi Uhlenhaut, the well-known chief development engineer, and Mercedes’ head of design (as opposed to styling), Josef Müller. The important first steps, such as minimum and maximum dimensions and outline specifications, were finalized in a series of meetings that took place a few months later, in the middle of September. Following this, Nallinger had a solid set of guidelines to pass down to the various departments involved.

As well as having to incorporate the latest passive safety technology and provide more room for passengers, which almost meant designing the car from the inside out, ultimately the men in the design department needed something that would not simply bring things up to date, but also see the company through the next ten years while at the same time be instantly recognizable as a Stuttgart thoroughbred.