Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

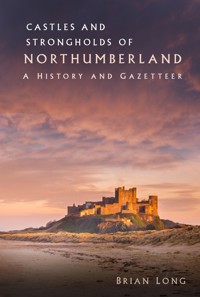

Much more than an 'excellent gazetteer'; this detailed study of the county's castles, monuments and towers shows who was responsible for the defence of the Anglo-Scottish border whilst Henry V was at Agincourt. Subsequent surveys show how in 1584 Christopher Dacre forwarded a bold project that linked a string of towers forming a defence against marauding Scots, suggesting new towers to stop gaps, with a 'dyke or defence' joining them like a latter-day Hadrian's Wall. Beyond this line were the many Peles or Bastles, home to the headsmen of the notorious reiving families, who were cursed in 1525 by bishops of Durham and Glasgow as punishment for their brutal way of life, giving rise to much legend and romance. Meanwhile, polite society occupied the large castles nestled amongst the coastal area still standing today for all to see. This history and gazetteer, with over 500 entries and plentiful illustrations and plans, will enhance your understanding of the history of the borders and their proud, turbulent past.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 396

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 1967

This edition published 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Brian Long, 2024

The right of Brian Long to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9701 0

Typesetting and origination by The History Press.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Dedicated to Laura Gatling

Without you this would not have been complete

Alnwick Castle viewed from Robert Adam’s Lion Bridge with the famous Percy Lion in the foreground.

Contents

Preface

I Being Introductory

II Definitions

Fortalice

Tower

Barmkin

Barmkin, Barmekyn, Barnekyn

Vicars’ Peles

Bastles

Peles

Resident Reivers

Peles and Bastles: A History

III Evidences

IV Gazetteer

Appendices

Appendix I: List of Maps

Appendix II: List of Illustrations

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Preface to the Second, Revised and Enlarged Edition

Castles of Northumberland was first published in 1967, to be followed in 1970 by Shielings and Bastles by Ramm, McDowall and Mercer. Twenty years later (1990), Peter F. Ryder produced his excellent report Bastles and Towers for the Northumberland National Park, all increasing our knowledge and understanding.

Over the years the number of recognisable remains and sites of peles and bastles has grown. My own interest in this field led to many visits and surveys while working for the Forestry Commission in the vast forests of Kielder, Redesdale, Tarset and Wark. I recorded everything from shielings to deserted villages as well as my main interest: the many peles and bastles of the county.

This new edition, Castles and Strongholds of Northumberland, is the result of my continuing quest and the accumulated knowledge of numerous historians and archaeologists, to whom we should be grateful.

Brian Long

Chapter I

Being Introductory

Northumberland has more castles, fortalices, towers, peles, bastles and barmkins than any other county in the British Isles. Castles of all periods were the private residences and fortresses of kings and noblemen. The fact that they were private residences was the principal difference between them and their predecessors, the Anglo-Saxon burghs, which were fortified towns, etc., such as were at Heddon, Yeavering and Bamburgh. Their private nature is again the distinguishing factor between them and forts erected at a later date by kings and governments for national defence. The towers, peles, bastles and barmkins were also private residences fortified by small, not so powerful lords, or by rich farmers and landowners as a means of defending themselves from raiding parties and securing their cattle in times of such raids.

Motte-and-Bailey Castles

Many castle sites are either not known or can only be traced as names on a map or a few green mounds in a field. Indeed, many of these green mounds never had fortifications of stone erected on them and only existed as the motte-and-bailey castles of the Norman invaders, our first castle builders. Whatever the precise plan of a motte-and-bailey castle, the earthworks in themselves were a formidable defence crowned with timber stockades. The outer fringes of these castles, the counter-scarp, on the outside of the ditches of both motte and bailey, also had their bristling defences of pointed stakes set at angles and interwoven brambles.

Motte-and-Bailey Castles with Map References (see Figure 1, p.12)

D.35

Alnwick

B.18

Bamburgh

B.1

Berwick

E.38

Bellingham

G.23

Bellister

F.40

Bolam

F.19

Bothal

H.6

Bywell

D.42

Callaly

A.12

Carham

E.18

Elsdon

B.2

Fenham

D.4

Fowberry

E.50

Gunnerton

G.13

Haltwhistle

C.15

Harbottle

D.15

Ilderton

F.21

Mitford

F.20

Morpeth

H.12

Newcastle

A.2

Norham

H.8

Prudhoe

D.56

Rothbury

E.55

Simonburn

D.13

South Middleton

H.19

Styford

?

Tiefort1

D.32

Titlington

A.1

Tweedmouth

H.14

Tynemouth

G.53

Warden

A.16

Wark on Tweed

E.53

Wark on Tyne

D.46

Warkworth

C.5

Wooler

Four images showing the development of motte-and-bailey castles with the motte at Dinan, the motte-and-bailey at Elsdon, a reconstruction of a motte-and-bailey castle and Warkworth Castle with the later stonework following the original earthworks.

The sketch of the motte at Dinan is based on the Bayeux Tapestry and shows a timber keep surmounting an earthen mound with a moat. Elsdon Castle is shown in this old drawing with a bold motte and a larger but lower bailey with no trace of the timber castle that must have capped them. A complete motte-and-bailey castle with moated motte-and-bailey is shown with a shell keep on the motte and great hall and other offices in the bailey, all of timber construction.

Figure 1: Map of Northumberland showing the distribution of motte-and-bailey castles in the county.

Castles of Northumberland

Upon the summit of the motte or mound, within the stockade, usually rose a wooden tower, which was the residence of the lord and the ultimate stronghold and vantage point of the castle by reason of its superior height.

The exact time and place or origin of this type of fortification is unknown. A castle of this type was mentioned for the first time in ad 1010 and stood on the banks of the Loire in France. It was built by a man skilled in military affairs whose name was Fulk Nerra. He was also the first man to employ mercenary soldiers. It cannot be denied that a motte is a fortress for a man who wishes to defend his family and close friends from all would-be enemies, whether other lords or his own rebellious retainers. Whatever its origin, the motte was in wide use in Normandy before William conquered England.

The tower on the motte was not always a crude and uncomfortable lodging on stilts as stood at Durham in the castle of Prior Laurence: ‘Four posts are plain, on which it rests, one post at each strong corner.’ Many were comfortable tower houses, as described by Lambert of Ardres in 1117:

Arnold, Lord of Ardres, built on the motte of Ardres a wooden house, excelling all the houses of Flanders of that period both in material and in carpenters’ work. The first storey was on the surface of the ground, where were cellars and granaries, and great boxes, tubs, casks and other domestic utensils. In the storey above were the dwelling and common living rooms of the residents, in which were the larders, the rooms of the bakers and butlers, and the great chamber in which the lord and his wife slept.

Adjoining this was the private room, the dormitory of the waiting maids and children. In the inner part of the great chamber was a certain private room, where at early dawn, or in the evening, or during sickness, or at time of bloodletting, or for warming the maids and weaned children, they used to have a fire … In the upper storey of the house were garret rooms, in which on the one side the sons (when they wished it) and on the other side, the daughters (because they were obliged) of the lord of the house used to sleep. In this storey the watchmen and servants appointed to keep the house also took their sleep at some time or other. High up on the east side of the house in a convenient place was the chapel, which was designed to resemble the tabernacle of Solomon in its ceiling and painting. There were stairs and passages from storey to storey, from the house into the kitchen, from room to room and again from the house into the loggia, where they used to sit in conversation for recreation, and again from the loggia into the oratory.

It may be noted that neither the Bayeux Tapestry, nor indeed many of the contemporary accounts, mention or show the bailey. It should not be deduced from these facts that in most castles the bailey did not exist, but it should be taken as an implication of the immense importance of the motte both militarily and socially. The bailey must have been essential for stables, barns, smithies and affording shelter for the garrison and its supplies in most, if not all, of the early Norman strongholds.

As mentioned above, the Bayeux Tapestry shows several of these castles with their towers on the motte and bridges in position. The pictures of the siege of the castle at Dinan shows just how vulnerable they were when fire was used. There can be little doubt that the walls were hung with wet hides to prevent them catching fire. One of the many tragedies that must have overtaken these houses and their besieged occupants happened in 1190 when the Jews of York were attacked by a mob and had taken refuge in the motte, and many of them perished when it was fired.

Motte-and-bailey castles were cheap and quick to build but a castle of importance required more permanent defences, and as timber in contact with damp soil rots quickly, the second build of such a castle would at least be on stone sleeper walls if not entirely rebuilt in stone when circumstances allowed. It was at this time that many sites were abandoned in favour of stronger and healthier sites. Elsdon Castle, the best motte-and-bailey in Northumberland, never had stonework built on it as the occupants moved out when the timber decayed. The remaining mounds, known as the Moat Hills, are worthy of inspection.

The next step in castle building came about by a change of materials rather than tactics, and the keep-and-bailey castle came into being. The keep, normally, was a large square stone structure taking the place of the motte, or incorporating it in its own defences, as at Warkworth. The plans of these castles were the same as those of timber, though as the first urgency of the conquest declined and the lords began to seek the comfort and safety of stone, quite a number of the original sites were abandoned, as was Elsdon, for safer and more suitable ones.

The main gate, the most vulnerable point of the bailey, was the first to be strengthened by a stone tower. A strong square tower, beneath which ran the entrance passage, would be built. Then came the bailey walls enclosing the site; this enabled the occupants to work in safety on the keep and other offices. Norman ramparts can still be seen under the successive layers of stonework of nearly every period at Alnwick, Warkworth, Morpeth, Mitford and Norham. As mentioned above, keeps were normally large square structures, as at Newcastle, Norham, Bamburgh and Prudhoe. The normal arrangements in these large towers or keeps can be seen to advantage at Newcastle. It is obvious that much in the way of comfort was sacrificed, but in days of peace there would be other more comfortable lodgings in the bailey. Because of their weight, great towers and keeps were seldom placed on the earlier mounds as at Warkworth. To replace the security offered by the height of the motte, the entrance to the later stone keeps was often on the first- or even the second-floor level and housed by a forebuilding.

Bamburgh, built on its rock, was so inaccessible as to be safe with its entrance on the ground floor, or so the builders thought. No two keeps are exactly the same, but all are similar in many respects, internally and externally. They have shallow buttresses in the centre of each side and at the corners. The corner ones often terminate in small angle turrets, but the bases of all of them are splayed. The walls were of great height so as to protect the high-pitched roof from fire arrows. In some castles, such as Warkworth, the keep was so large and of such excellent design that it may have been in general use and at least would have been much more comfortable than most.

Shell Keeps

The keep was the strongest point of the castle and had to be a self-sufficient unit capable of separate and successful defence. The simplest form of keep, placed upon the motte, its stonework following the line of the timber stockade, was known as a shell keep. Within this strong enclosure, the timber tower house was replaced by strong buildings either for the residence of the lord or the defence of the keep. Like the buildings in the bailey, they were ranged against the inside of the wall so that the centre of the enclosure was left free. Castles in Northumberland with a shell keep include Alnwick, Mitford and Wark on Tweed.

There are traces of the buildings that once lined the walls of the keep at Mitford but in the thirteenth century they were removed to make way for a five-sided tower that stood in the centre of it, almost filling it.

Sieges

Few methods of siege warfare could be used against the massive keeps but keeps and bailey walls were all vulnerable to mining. A passage or sap would be driven under the walls or across the corner of a keep and the walls supported by timber frames. When the passage was complete, a fire would be lit in it to destroy the supports and so bring down the wall, exposing the defenders. A sap of this kind was found at Bungay in Suffolk but seems to have been built or engineered by the occupants so as to destroy the castle in case of surrender.

To counter this threat, as previously mentioned, the corners of keeps had buttresses that projected from the wall almost like small towers. In some cases, as at Warkworth, towers were built projecting from the centre of each face so as to cover the walls. The bases of square keeps were splayed to prevent the sappers from coming into contact with the actual wall. This also had the advantage that missiles dropped from above would bounce off its surface at unpredictable angles into the shelters used by the sappers. The keep at Newcastle has a widely splayed base. During the religious wars (First Crusade, 1096) in the Near East, the knights noticed how walls were protected by projecting towers at intervals along their outer face, and they had to turn to such weapons as the ballista, trebuchet and belfry. When they came home, they in turn defended their castles against these weapons.

The shell keep at Alnwick Castle with a small central courtyard and building of many periods and styles forming the outer wall (the shell).

To break into such a castle, the moat first had to be filled in under the cover of bows and stone-throwing machines to enable the sappers to reach the base of the wall; once at the foot of the wall, this had to be breached by one of a number of methods such as sapping, or crossed by the use of the belfry (a high wooden mobile tower), which was pushed up to the wall. To combat this problem, the defenders built higher walls to prevent the use of scaling ladders and the belfry. Now all that remained was to protect the berm, or space immediately in front of the wall, since this was the spot attacked by sappers. One device was the brattice or hoarding, a covered wooden gallery built out from the top of the wall supported on horizontal wooden brackets. The holes for these timber supports can be seen in the south wall at Warkworth. These galleries had holes in their floors, through which missiles could be dropped on to attackers.

The gatehouses of Newcastle and Warkworth are other results of these observations during the Crusades. The towers on the gatehouse at Warkworth are polygonal, while those at Newcastle are semicircular. Of the older, Norman gates, the only ones remaining are those to the shell keep at Alnwick, and the gates of the outer baileys of Prudhoe and Norham.

Gatehouses

The castles of Edward I in Wales, with no keeps but large gate towers, were never completely copied by the Northumbrians of the time, and the greatest achievement in that field was Dunstanburgh. Work at Dunstanburgh began in 1314 and it had no other keep except the gatehouse. Other examples of the gatehouse keeps are Bothal, Tynemouth and Bywell of a later date. The disadvantage of this arrangement was that the gatehouse was the first line of attack and the last resort of the holders who must live in the midst of the battle because there was no other lodging strong enough included with the castle walls. John of Gaunt closed the gate at Dunstanburgh and built a complicated barbican at the side leading to a gate a little distance away. Other castles with barbicans added to their gates were Tynemouth, Prudhoe and Alnwick, which also had a barbican to the shell keep. With the uniting of the crowns, peace came to the border and castles were abandoned for the more comfortable houses of the type that the south of England had enjoyed for the past two centuries.

Houses

The plans of the houses of the period were remarkably uniform, whether large or small, castle or hall. The main feature was the hall. Halls could be on the ground floor or raised on a cellar and approached by steps and open to the rafters. At one end was the dais where the lord and his family ate. Others ate and slept in the marsh, the area of the hall below the dais. In the early days an open hearth would blaze in the centre of the floor, the smoke escaping where it could. At the other end of the hall was a screen, behind which were the entrance doors and the doors leading to the buttery and pantry. Above the screen was a gallery or room.

The solar, or private room, was at the same end as the dais and was reached through a door behind the dais. Other rooms and a chapel were added where the site would permit. Hall houses were built in the thirteenth century but they had to be strengthened and fortified at a later, not quite so peaceful, date. Of outstanding interest is Haughton Castle, which under fourteenth-century fortifications hides a large hall house of the ‘palas’ type. Remains of a smaller house can be seen at Heaton and are known as King John’s Palace. Another house forms part of Featherstone Castle.

Of fortified manor houses, by then becoming very popular in the south, Northumberland can boast one of the earliest examples: Aydon Castle, a very extensive house in a well-defended position above the Cor Burn, which winds round three sides, with very steep banks up to the house. The castle, or house, had no keep or even strong towers to protect its curtain wall. Edlingham consisted of a rather fine hall house but unlike Aydon had a keep attached at a later date.

The OED on Peles, Peels or Vicars’ Peles

If you can’t find ‘pele’ in your edition of the Oxford English Dictionary, just move on to ‘peel’, where they say that in early usage it was a pale or stake. Later it was a palisade formed using pales or stakes, or even a moated enclosure or small castle.

They go on to say that modern writers use ‘peel’ to describe a massive square tower or fortified dwelling occupied by sixteenth-century borderers as a defence against forays. The result is a tendency to call all towers large or small pele towers, be they the houses of local headsmen, the mansion of the vicarage or home to other person of standing. Hidden in this changing interpretation is the present belief that early peles consisted of moated sites with a timber palisade and houses set within their own small island enclosure.

The OED does not mention vicars’ peles but I read into the above that the later peles or towers were built using stone, with some having a barmkin or stockade of stone built around them. This resulted in what I consider correct: that only towers with an enclosure in which they stood can correctly be termed as pele towers; that is, a tower within a palisade, a stockade or a barmkin.

Towers

Such houses as Aydon were not to be the rule, however, as strife was almost continuous in the border counties during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, and towers were still being erected in the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century. Most of these towers were of the same design as the square keeps of the Normans, regardless of the period in which they were built, and observers may find them difficult to date. Many churches had towers either built for defence or as places of refuge in time of war. Churches with such towers are Ancroft and Edlingham. Towers were also built at Carham and Farne.

List of Towers (see Figure 2, p.22)

Abberwick

D

Acton

D

Adderstone

B

Akeld

C

Alnham Vic

C

Alnwick (St Mary’s)

D

Alwinton Vic

C

Ancroft Vic

B

Antichester

C

Bamburgh Vic

B

Barrow Bavington

E

Beadnell

D

Beaufront

G

Bebside

F

Bedlington

F

Belford

B

Belsay

F

Benwell

H

Berrington

B

Bewick

D

Biddlestone

C

Birks

E

Birtley

E

Bitchfield

F

Blanchland

G

Blenkinsop

G

Bolam

F

Bolt House Vic

F

Branxton

A

Buckton

B

Burnbank (Bought Hill)

E

Burradon (Coquetdale)

C

Burradon (N. Tyneside)

F

Callaly

D

Caraw

E

Carham

A

Causey Park

F

Charlton (South) Vic

D

Chatton

D

Chatton Vic

D

Cheswick

B

Chipchase

E

Chollerton

E

Choppington

F

Clennell

C

Cocklaw

E

Cocklepark

F

Coldmartin

D

Corbridge Vic

H

Cornhill

A

Cotewalls

C

Coquet Island

D

Coupland

A

Craster

D

Crawley

D

Cresswell

F

Dally

E

Darques

E

Detchant

B

Dilston

G

Downham

A

Duddo

A

Dunstan

D

East Shaftoe Hall (Belso)

F

Earle

C

East Ditchburn

D

East Woodburn

E

Edlingham Vic

D

Elliburn

F

Ellishaw

E

Elsdon Vic

E

Elswick

H

Elwick

B

Embleton Vic

D

Eslington

D

Fairnley

F

Fallowlees

F

Falstone

E

Farnham

C

Farne Island

B

Featherstone

G

Fenham

B

Fenton

A

Fenwick

F

Ford Vic

A

Fowberry

D

Goswick

B

Great Ryal

D

Great Swinburn

E

Great Tosson

D

Green Leighton

F

Grindon Rigg

A

Gunnerton

E

Halton

H

Haltwhistle

G

Harnham

F

Harterburn

F

Hartington

F

Hazelrigg

B

Healey

H

Heaton

H

Heaton (Old Heaton) Castle

A

Hebburn (Hepburn)

D

Hedgeley

D

Hefferlaw

D

Hepple

C

Hepscott

F

Hesleyside

E

Hethpool

C

Heton

B

Hobberlaw

D

Holburn

B

Hoppen

B

Howick

D

Howtel

A

Hulne Abbey

D

Humbleton

C

Ilderton

D

Ingram

D

Kilham

A

Kirkharle

F

Kirkley

F

Kirknewton

C

Kirkwhelpington Vic

F

Kyloe

B

Lanton

A

Lemington

D

Little Bavington

E

Little Harle

F

Little Haughton

D

Little Swinburn

E

Long Haughton Vic

D

Longhorsley

F

Lowick

B

Low Trewitt

D

Meldon

F

Middleton (Bamburgh)

B

Middleton Hall

D

Mindrum

A

Morpeth

F

Nafferton

H

Nesbit

A

Nether Trewhyt (Low Trewitt)

D

Netherwitton (High Bush)

F

Newbiggin

A

Newbrough

G

Newburn

H

Newlands

B

Newstead

D

Newton Hall

H

Newton Underwood

F

Newtown

D

Ninebanks

G

North Middleton

F

North Sunderland

B

Nunnykirk

F

Old Bewick (Bewick)

D

Otterburn

E

Overgrass

D

Paston

A

Ponteland Vic

F

Portgate

G

Preston

D

Prendwick

D

Ritton White House

F

Rock Hall

D

Roddam

D

Roseden (Ilderton)

D

Rothley

F

Ryal

F

Saint Margarets (Alnwick)

D

Scremerston

B

Seaton Delaval

F

Seghill

F

Settlingstones

G

Sewingshields

E

Shawdon

D

Shield Hall

G

Shilbottle Vic

D

Shoreswood

A

Shortflat

F

Simonburn Vic

E

South Charlton Vic

D

Stamfordham

F

Stanton

F

Starward

G

Swinburn

E

Thirlwall

G

Thornton (Newbrough)

G

Thornton (Thornebie)

A

Thropton

D

Tillmouth

A

Titlington

D

Togstone

D

Tosson

D

Troughend

E

Tweedmouth

A

Twizell

A

Wallington

F

Walltown

G

Walwick

E

Weetslade

F

Weetwood

D

Welton

H

West Lilburn

D

West Thornton

F

West Whelpington (Kirkwhelpinton)

F

Whalton Vic (Rothbury)

F

Whitlow

G

Whitton Vic

D

Whittingham Vic

D

Widdrington

F

Witton Shield

F

Wooler

C

Wylam

H

Yeavering

A

Figure 2: Map of Northumberland showing the distribution of towers, vicars’ peles and hall houses. Towers were the most numerous type of fortified house in the county.

1Tiefort: This castle is mentioned in the Histoire des Ducs de Normandie, and has been translated as being either Styford, Tynemouth or Tweedmouth. The only other clue is the date of 1216 when the Histoire was written.