56,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

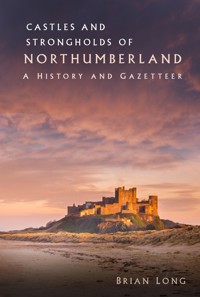

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

This book is much more than just a history of the high-quality cameras and lenses that have made the Nikon brand a household name; it is also a chronicle of the birth of this most famous of Japanese photography equipment manufacturers and the way in which it has evolved over 100 years to keep abreast of advances in technology and ahead of the competition. This fully updated and expanded third edition is heavily illustrated throughout with rare archive material from around the world, and augmented by a feast of original shots and pictures of the cameras in use. The text is backed up by extensive appendices containing everything the avid Nikon collector needs to know. A celebration of the birth of this most famous of Japanese photography equipment manufacturers Nikon 2017 was the 100th Anniversary of Nikon. Fully updated and expanded third edition for 2018.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

NikonA CELEBRATION

BRIAN LONG

REVISED AND UPDATED THIRD EDITION

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2006 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2018

Third edition 2018

© Brian Long 2006, 2011 and 2018

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of thistext may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 470 4

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

INTRODUCTION

1 THE EARLY DAYS

2 THE RANGEFINDER YEARS

3 THE FIRST SLR MODELS

4 THE F3 AND F4 ERA

5 NEW F MODELS AND THE DIGITAL REVOLUTION

APPENDICES

I RANGEFINDER SPECIFICATIONS

II RANGEFINDER LENSES

III SLR PRO BODY SPECIFICATIONS

IV THE REGULAR SLR MODELS

V THE DIGITAL SLR BODIES

VI SLR LENSES

VII SPEEDLIGHT REVIEW

VIII THE NIKONOS SYSTEM

IX MODERN POCKET CAMERAS

X THE COOLPIX RANGE

XI THE NIKON 1 SYSTEM

INDEX

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I’VE NOW WRITTEN MORE than forty motoring books over the last two decades, usually concentrating on the history of individual models. I’ve also done company histories that have included fields outside the automotive realm, but this is my first book on cameras. As such it would simply not have been possible to complete this project without the help and support of many people.

A 1965 advert showing the legendary Nikon F and a selection of lenses from the time.

Special mention must be made of Kazuhiko Mitsumoto (professional photographer, motoring journalist, TV personality, and all-round good guy), who put me in touch with Nikon, and as such put his enviable reputation on the line for me. Another good friend of mine, Yoshihiko Matsuo (designer of the Datsun 240Z and a real old camera buff), has followed the project closely, not to mention the staff at my favourite camera shops – Sanai Camera in central Chiba, and Ohba Camera in Shimbashi, Tokyo.

I’ve even managed to inspire people who weren’t really into cameras as we’ve talked about the project – former car engineers catching the bug in much the same way as I did many years ago (sorry, Koby!) – even to the point of suggesting we need more general awareness of what Nikon has achieved from a technical angle.

As you can imagine, the pressure to deliver the goods is therefore every bit as overwhelming as it is with one of my motoring titles. In this regard, I am so lucky to have Kenichi Magariyama as my contact at Nikon head office. Now in charge of the Web Communication section, Magariyama-san is a former camera designer who dearly loves to promote the Nikon brand.

While most of the advertising has come from either my collection or that of my stepfather in the States, Ken Hoyle, virtually everything else has been sourced through Nikon in Japan. For this, both I – and you, the reader! – have to thank Mikio ‘Mickey’ Itoh for going to great lengths to satisfy my many requests for photographic material and to fill in the gaps in my information. Itoh-san is a former optical measuring instrument engineer who now looks after Nikon’s archives. His enthusiasm is what has made this book into something I can be proud of, and I only hope that he, Magariyama-san et al. will also be pleased with the results.

Without the help of my wife, Miho, it would have been almost impossible to relay the Japanese side of the story. Between us, we’ve gone through more than 10,000 pages of reference material! One day I must get around to thanking her properly for all the translation work she’s done for me, as well as making contact with the good people at the JCII Camera Museum & Library (in particular, Shinji Miyazaki and Yoshio Inokuchi), Ei Mook and Bungei Shunju, along with ace photographer Bunyo Ishikawa.

BRIAN LONGChiba City, Japan

INTRODUCTION

AS A TEENAGER, PHOTOGRAPHY was one of my main hobbies. In my younger days, armed only with a screw-mount Praktica, I’d dream of owning an F3, and the F4 simply blew my mind when it came out. Unfortunately work soon consumed much of my life, and the opportunities to take pictures – other than those related to my job – became fewer and fewer as the years rolled by. The fascination with photography, however, remained as strong as ever and, now working with the Nikon system, I found myself being drawn to the beauty of the cameras and lenses rather than the act of taking shots, which, in reality, I was never that good at anyway. Coming from an engineering background, I could appreciate the dedication and skill that went into these miniature sculptures: my love of the Nikon brand stems from this appreciation.

It took me a long while to buy my first F4, but, during my time in Japan and the gradual shift from user to user/collector, it has been augmented by about thirty more Nikons, all but one of them (the D100 for everyday use) older than the F4, and many of them older than me! I keep telling my poor wife that cameras are really living things, and they breed when no-one is looking. Of course, she just assumes I’m crazier than she originally thought, but how else can you explain how they keep mysteriously appearing in the house at such regular intervals?

At the same time, Nikkor lenses have gradually filled my cabinets. After my first batch of film was developed using these fabulous masterpieces, there was to be no turning back – the quality of the Japanese-made Nikkor is simply beyond reproach.

As well as enjoying the modern zooms for work, I’m constantly amazed by the function and beauty of the brass screw-mount 13.5cm Nikkor I have attached to my pre-war Leica – this combination looks and feels as good today as it did more than half a century ago. And it never ceases to impress me that the early 5cm lens seems to weigh almost as much as the Nikon S it is mounted on!

I’m very lucky to be surrounded by so many like-minded friends in Japan. Members of the RJC (the Researchers’ & Journalists’ Conference of Japan) and JAHFA (the Japan Automotive Hall of Fame), two organizations with which I’m heavily involved, are often obsessed not only with cars, but also share my enthusiasm for old cameras and mechanical watches. Most of these guys, however, were using Nikons for a living before I was born, and I’m looking forward to the day when my collection will equal that of some of my esteemed colleagues.

I hope this book is a reflection of why so many of my friends and I love and respect the Nikon brand. I will try to present a picture of what makes it special in a format that will inspire you, and make you want to thumb through the pages, not just to learn technical specifications, but to wallow in the photographs and wonderful adverts from Nikon’s earliest days to the present.

This publication does not include any tips on how to get the best from each camera or lens – there are plenty of good books on the market that already cover this aspect, written by people far better qualified than me – but it does include the company’s history, the way its products have developed over the years, and all the little details that tend to absorb collectors.

Notes on the Third Edition

Time flies, and I don’t think either Crowood or myself had realized just how much of it had gone by until a friend in London got in touch to say he’d been told that the second edition of the book had now sold out. Asked when the new version was coming out, I was unable to respond, but here’s the ultimate answer – a further expanded and revised edition that takes the story up to the end of 2017. The year 2017 holds a special significance, of course, as it marks the centenary of the company, and I was both surprised and honoured to be asked to be a small part of the 100th anniversary celebrations by Nikon Europe. Here’s to the next 100 years…

INTERNATIONAL EXCHANGE RATES

YEAR

USA

UK

GERMAN

FRENCH

EEC

SWISS

$1-

£1-

DM1-

FF1-

€1-

SF1-

1950

360

1000

85

90

_

85

1955

360

1000

85

85

-

85

1960

360

1000

85

75

-

85

1965

360

1000

85

75

-

85

1970

360

865

85

65

-

85

1975

270

620

100

65

-

100

1980

220

485

110

50

-

120

1985

240

290

80

25

-

95

1990

140

270

90

25

-

110

1995

100

150

60

20

-

75

2000

110

165

-

-

105

65

2005

105

205

-

-

140

90

2010

90

135

-

-

110

80

2015

120

175

-

-

135

125

This table shows spot rates for selected years, with the approximate amount of Japanese yen (¥) each specified currency would buy during any given year. This overview will help put much of the text and details in the appendices into perspective.

The logo used on Nippon Kogaku’s very early letterheads.

The symbol used on the company flag, designed in 1930.

The official Nippon Kogaku logo, circa 1930.

The logo adopted just after the birth of the Nikon camera.

The English and Japanese typeface styles used from May 1954.

The revised company logo, widely adopted from 1962.

An alternative logo to the 1962 version, used from July 1967.

The English and Japanese typeface styles registered in 1987 but used from April 1988, plus the new company logo introduced at the same time.

CHAPTER ONE

THE EARLY DAYS

JAPAN HAD BEEN LARGELY isolated from the outside world until the American commander, Commodore Matthew C. Perry, first sighted the Land of the Rising Sun from his ‘black ships’ in 1853. Perry’s visit, basically one to demand trading rights, coincided with the people’s wish to see an end to the feudal society that had existed in Japan for more than 600 years. The days of rule by the sword were numbered, and the brief war of 1868 (known as the Meiji Restoration) finally put an end to the Tokugawa regime.

For several years before the Meiji Restoration, however, cities open to business with the West were few and far between, including only Yokohama (close to where Perry first dropped anchor), Kobe, Hakodate, Niigata and Nagasaki, the oldest trading post of the Edo era (1600–1868). If one goes today to the northern port of Hakodate, which escaped the heavy bombing Japan suffered during the Second World War, one can see an eclectic mix of architecture from around the world, providing the visitor with a glimpse into the past when this great nation first felt foreign influence.

Mutsuhito, or Emperor Meiji, was only fifteen years old when he took up the role of head of state in Edo (later renamed Tokyo) following the death of his father a year earlier, becoming the 122nd emperor. The Meiji era (1868–1912) brought about a new dawn and, as time passed, a far greater willingness to deal with and adopt the ways of the West. Emperor Meiji built up a particularly good relationship with Britain and other parts of Europe, helping Japan to model its railways and roads, its postal system and growing navy on that of the UK. Grand, European-style buildings sprang up in the business quarters of the major cities, with Western clothing gradually replacing traditional Japanese attire in the country’s bustling city streets as the nineteenth century came to a close.

This interesting Tokyo street scene from before the Great Kanto Earthquake shows the European influence on Japanese life brought about by the Meiji Restoration.COURTESY NATIONAL SCIENCE MUSEUM, TOKYO

KOYATA IWASAKI.Born in 1879, Iwasaki was the head of the Mitsubishi zaibatsu at the time Nippon Kogaku was formed. He was largely responsible for the company’s creation, bringing together Tokyo Keiki, Iwaki Glass and Fujii Lens, and providing a great deal of financial support to get the business off the ground.

YOSHIKATSU WADA, the inspirational leader of Tokyo Keiki and Nippon Kogaku’s first President. Although his time in office was quite short, he managed to persuade Koyata Iwasaki to become more personally involved with Nippon Kogaku. Given Iwasaki’s business clout, this doubtless had an effect on order levels.

It was an exciting era of change and growth, but, unfortunately, Emperor Meiji fell ill at the start of 1912 and died that July. His son, Yoshihito, was duly sworn in as Emperor Taisho. Europe, which provided Japan with a great deal of trade and also supplied it with the majority of its industrial and military requirements, however, was about to be plunged into turmoil.

The First World War – a Catalyst

The Russo-Japanese war of 1904–5 had been fought and won by Japan with British-built ships and armaments, German and French binoculars, and, notably, English rangefinders. European countries were quick to realize that modern warfare called for good optical equipment – after all, firing one shell on target is far more effective than firing 10,000 if they all miss!

During the years following its victory over Russia, the Imperial Japanese Navy grew in strength, but, despite the fact that Japan had been studying the production of optical equipment since 1892 (such as microscopes, cameras and surveying instruments), virtually all of its military technology continued to be bought in from abroad.

This situation was all well and good until the First World War brought an abrupt halt to supplies from Europe. When Germany and her supporters first clashed with the Allied forces in the summer of 1914, military exports stopped almost overnight. Indeed, most of Europe’s trade with the Far East was suspended, as domestic considerations were given priority in countries with which Japan was in league, and Germany became the enemy on 23 August 1914.

This unexpected development in Europe speeded up Japan’s resolve to produce its own military equipment. In fact, several high-ranking officers had been saying that Japan needed its own optical industry for some years before the First World War. One of the key visionaries to preach the importance of becoming self-sufficient in this area was a naval officer named Akira Ando, who approached the Tokyo Imperial University in 1906 to study mathematics and physics with a view to furthering lens technology. His later role as an armaments inspector only strengthened his views regarding the need for domestic expertise.

With the help of Tokyo Keiki Co. and Fujii Lens, Ando successfully made a pair of rangefinders to his original designs in 1913. By this time a few small Japanese companies were commercially producing microscopes and camera obscura (traditional camera bodies). Although high-quality camera lenses and shutters were still beyond the ability of these pioneering concerns, the seeds for an optical industry had definitely been sown.

When the time came to equip Japan’s latest battleship, Haruna, with its telescope and rangefinders, Britain was at war and the order could not be fulfilled. The Navy therefore approached Fujii Lens regarding the telescope on the main armament, and Tokyo Keiki for the 1.5m and 4.5m rangefinders. While the 1.5m item was duly produced in 1915, the larger rangefinder proved too difficult to make with such limited experience. Ando’s worst fears had been confirmed, but Japan took the initiative to send two naval engineers to Britain to learn as much as possible about rangefinder technology.

Meanwhile, the First World War brought a great deal of business the way of Japan’s fledgling optical firms, as the UK, France and Russia ordered items such as field binoculars from their Japanese ally.

Ando, now a Rear Admiral, was Japan’s naval attaché in England during the war. He learnt that a Fujii Lens representative was in America, exhibiting binoculars at the exposition held to celebrate the opening of the Panama Canal, and requested a meeting in London to obtain a number of military contracts with the Allies. Various French prisms and other items were procured from the British government, and a deal signed and sealed.

The problems only really started when supplies of optical glass (originally ordered from Germany) dried up, and shipments from other European countries could not get through, largely due to submarine attacks. Fujii Lens was therefore forced into recycling old instrument lenses and developing flint glass with Tokyo Denki – the forerunner of Toshiba.

In the background, Iwaki Glass was in the process of producing optical lenses by 1914. The company, today recognized as one of Japan’s foremost spectacle glassmakers, had been founded in 1883 and manufactured all manner of household glassware; it also supplied industrial products as and when required, and was held in high regard by the Japanese Navy for its large mirrors.

The Imperial Navy itself commissioned the Tokyo Kogyo Institute of Technology to look into the process of manufacturing lenses, but, after a number of unsuccessful attempts at producing suitable glass, this line of research did not provide anything worthwhile until February 1918. Ironically, the Imperial Army had already perfected the art of making lenses by 1915, and after a joint conference between officers of both forces, the technology was duly handed over to the naval authorities, who were later charged with developing the nation’s military optics.

The Birth of Nippon Kogaku

In 1916 the Imperial Navy approached Mitsubishi with a view to building a submarine to combat the threat from German U-boats. A key problem, however, was how to secure a suitable periscope, as Japan’s allies were already overstretched with their own domestic demands. This situation ultimately led to the formation of a Japanese company that could produce military optics, with Mitsubishi at the helm.

The rise of Mitsubishi was truly staggering. Founded in 1873, the Mitsubishi concern was born out of a small shipping company established by Yataro Iwasaki three years earlier. By the turn of the century, having gained state backing on the lucrative Yokohama–Shanghai route, Iwasaki was, without doubt, the most powerful shipping magnate in the whole of Japan. He was also clever: instead of using profits to buy more ships to augment the forty he already had in his fleet, he diversified. Mitsubishi duly secured large swathes of land, and bought into mining, railways, ironworks, chemicals and a number of financial institutions.

With Yataro’s nephew, Koyata Iwasaki, now in the President’s office, Mitsubishi continued to blossom. A Cambridge graduate who became head of the business empire (or zaibatsu) in July 1916, he encouraged Mitsubishi to build its first car (introduced in 1917, and based on the contemporary Fiat); the company was already producing ocean-going craft the equal of anything in the world at the time, and would later also turn its hand to the manufacture of aircraft.

With regard to the optics business, Koyata Iwasaki took advice from a number of sources and approached Tokyo Keiki, Iwaki Glass and Fujii Lens to propose the foundation of a joint-company. Tokyo Keiki and Iwaki Glass were happy to join Mitsubishi on this project, readily separating the related departments to start this new venture, but the Fujii brothers were fearful that this move would spell the end of Fujii Lens’s existence.

On 25 July 1917 Nippon Kogaku Kogyo KK – or Japan Optical Manufacturing Co. Limited – was formed with a capital of ¥2 million. Registered in the Koishikawa district of Tokyo, initially, three of the nine directors were from Mitsubishi (holding 20,010 of the 40,000 shares available) and six were chosen from Tokyo Keiki; the first President was Yoshikatsu Wada, the long-serving head of the latter firm.

By the following month Nippon Kogaku had taken over the optical instrument department at Tokyo Keiki and the industrial mirror section at Iwaki Glass, enabling business to begin with the existing workforce. At the same time a factory was duly secured at Oimachi (pronounced oh-e-ma-che) to the west of downtown Tokyo, covering a total of more than 17,000 square metres. It was an ideal site, with a recently built railway station serving a number of small manufacturing plants in the area, a good source of water readily available, and solid bedrock on which to build.

In December, three months after Koyata Iwasaki joined the Board as a named Director, the new concern started laying the foundations for a merger with Fujii Lens (then making about 150 telescopes and 1,000 sets of binoculars a month). It was brought into the Nippon Kogaku fold in early 1918, by which time the first phase of building at Oimachi had been completed.

Further investment from Mitsubishi took Nippon Kogaku’s capital up to ¥30 million by the summer of 1918, but events in Europe were about to change immediate requirements and the pace of lens development once more. On 11 November 1918 the armistice was signed, bringing an end to four years of warfare.

The Treaty of Versailles that was validated seven months later brought about an opportunity for German technicians to work in Japan, and vice versa. Fujii engineers duly went to Germany (as well as to Italy, France, England and America) and actually negotiated a possible merger with Carl Zeiss. This deal eventually fell through, but, having placed advertisements in various newspapers, they returned to Japan with eight German specialist workers, including the famous Max Lange, and a great deal of machinery.

The Post-War Years

Even though war had ended in Europe, Nippon Kogaku still had a number of ongoing military contracts to fulfil. Rangefinders, telescopes, periscopes, binoculars and searchlight mirrors continued to be produced for the Imperial Navy, along with vast quantities of binoculars for export.

The Nippon Kogaku works at Oimachi, pictured here in 1921.

The machine shop at Oimachi.

There were quality issues with the rangefinders, however, and there were still problems with making good optical glass. For a time the latter was imported from Germany, although a furnace and glass-testing department set up in a new, second factory at the Oimachi site (augmenting the original Nippon Kogaku works and the Fujii plant at Shiba in Tokyo) brought domestic production a step closer to reality.

Nippon Kogaku continued to grow, with excellent testing facilities and new factories springing up to allow the company to keep pace with orders. The future looked bright, too, with Japan planning a massive new fleet of battleships with no expense spared. Indeed, Japan’s defence budget accounted for 49 per cent of its annual spending at this time, against 23 per cent for the USA and Britain.

As expected, Nippon Kogaku received the order and budget for range -finders, but it was later cancelled after Japan signed up to the Washington Disarmament Conference in 1921. Altogether the Imperial Navy was to lose 244 vessels. While this setback involved no loss of money for the company, it was nonetheless a major disappointment, leaving many hands idle, and the grand project would doubtless have furthered technology.

This impressive 508mm (20in) telescope was built for the 1922 Tokyo Peace Memorial Expo, held in Ueno Park.

The company flag, designed by a Nippon Kogaku worker in 1930. There was also a company anthem released by Columbia Records.

Official notification of trademark approval, 1932.

There was another disaster in the early 1920s, but this time a natural one – the Great Kanto Earthquake of September 1923, the biggest in Japan’s history. Tokyo and the surrounding area were completely devastated. Tens of thousands were killed, and virtually all the infrastructure around Tokyo Bay, where the country’s population is concentrated, was laid to waste. The Nippon Kogaku factory was extremely lucky to escape serious damage and none of the workers was injured, although the rebuilding process and a general lack of food and water closed the plant for seventeen days when the business could ill afford any more bad luck. Sales fell to one half of 1922 levels, yet there were still wages to pay, as well as loans for foreign equipment and consultancy fees. These were indeed hard times.

Fortunately, the Japanese government and military leaders could see the worth of the optical industry and stepped in to save the company, passing on all existing programmes to Nippon Kogaku. There was a major reshuffle in the top management, including the resignation of the Fujii brothers in April 1924. The Army’s optical research facility, destroyed in the earthquake, was merged with that of Nippon Kogaku. With a series of new orders and a more streamlined operation (including the sale of some land and the retention of just one German technician, Heinrich Acht), the firm’s survival was secured, and the number of employees jumped from 600 in 1923 to 900 two years later.

By this time Nippon Kogaku was augmenting its income by producing shell casings for the military, and also accepted orders for optics for civilian use, such as camera lenses and microscopes, which like other scientific instruments were often sold under the Joico brand name in the early days. The company’s debts were eventually cleared and, in the background, with the Japanese government becoming more and more nationalistic, the future once again looked bright for the men at Nippon Kogaku.

LENS TYPES SUGGESTED FOR PRODUCTION BY HEINRICH ACHT

TYPE

ELEMENTS/GROUPS

APERTURE

FOCAL LENGTH

Anytar

4 in 3

4.5

7.5cm

10.5cm

12cm

15cm

18cm

Doppel Anastigmat

6 in 2

6.8

7.5cm

10.5cm

12cm

15cm

18cm

Dialyt Anastigmat

4 in 4

4.5

12cm

6.3

7.5cm

10.5cm

12cm

Flieger Objektiv

3 in 3

4.8

50cm

5.4

50cm

Porträt Objektiv

3 in 3

3.0

24cm

3.5

30cm

Projektions Objektiv

6 in 2

2.0

7.5cm

Nikkor Lenses

Nippon Kogaku’s lens technology was significantly advanced following the arrival of German technicians in Japan after the Great War, both from a design and manufacturing point of view.

Heinrich Acht, a microscope specialist when he was in Germany, was instrumental in the development of Nippon Kogaku’s camera lenses. Acht gathered together and analysed as many existing lenses as possible, compiling a handwritten database of all their technical details and optical performance. This information was then used as the starting point for the engineers in Japan and provided the foundation stone for the legendary Nikkor lenses.

A Type 14 1.5m rangefinder, introduced in 1925.

Through Acht’s research, which went some way towards justifying the fact that he was drawing the same wage as Nippon Kogaku’s President and every day was driven by a chauffeur to and from a specially built guest house, several types of lens were put forward for production (see table, above).

With Acht’s reference manual, scripted in Japanese, Kakuya Sunayama took over Acht’s work following his departure in February 1928. Sunayama continued to study the lenses of the famous European houses, bringing back a Tessar f/4.5 and Triplet f/5 from a research mission abroad.

In 1929 Acht’s theories and calculations were put to the test when the Japanese military requested a batch of lenses for aerial photography. The Flieger Objektiv details were refined, but the end result was not satisfactory. Ultimately a design based on the Triplet (with a slightly smaller element on one side of the centre lens, instead of two the same size forming the sandwich) proved to be much more successful, and the order for 50cm f/4.8 lenses was duly completed.

The Nippon Kogaku testing department, circa 1930.

The design department from the same period.

While the latter lens was being made, a 12cm f/4.5 Anytar was developed for general camera use. By 1931 the design had been perfected, with test results showing an optical performance that was easily the equal of the contemporary Zeiss Tessar, which was similar in construction. Encouraged by this success, further 7.5cm, 10.5cm and 18cm prototypes were made, and the decision to market them commercially quickly received the approval of the management.

Long-range 18cm binoculars dating from 1932.

The ‘Nikkor’ brand name was chosen for Nippon Kogaku’s lenses, ‘Nikko’ being a shortened version of the company name, with the ‘r’ being added on the end to give the product a European-sounding moniker. The application for the Nikkor trademark was sent off in 1931 and approved in April 1932.

The first Tessar-type Nikkors were available with focal lengths of 7.5, 10.5, 12 and 18cm for general use, while Triplet-type 50 and 70cm ‘Aero-Nikkor’ lenses were listed for aeronautical applications.

The new factory at Nishi-Oi, pictured in 1933. It was designed by the well-known architect Toshiro Yamashita.

Although sales were slow initially, this side of the Nippon Kogaku business was nurtured, ironically via the Kwanon concern. Named after the goddess of mercy, the first products to reach the shops carried the Canon badge. Canon (Seiki Kogaku) had approached Nippon Kogaku in November 1933, requesting help with lenses and a miniature rangefinder for a 35mm camera designed by Goro Yoshida. The work was duly completed. When Canon started producing its Hansa Canon at the end of 1935, Nippon Kogaku supplied the rangefinder and unusual lens mount, and, naturally, Nikkors were the lenses of choice, usually 5cm normals of f/4.5, f/3.5 or f/2.8 from August 1937 (serial numbers started with 5021, 5011 and 5021, respectively), or occasionally f/2s.

An early 10.5cm f/4.5 Tessar-type Nikkor lens.

The early Canons were generally sold through the Omiya Photo Supply business, which applied the Hansa trademark to most of its products (as indeed it does to this day). Interestingly, one of the Fujii brothers was employed by Canon as a consultant when the 35mm camera project was instigated, and even the enlarger in the picture is related to Nippon Kogaku – the 5.5cm f/3.5 lens being a Nikkor made for Canon with the Hermes name on it. This British advert dates from 1938.

The elegant Canon S of 1939. This example is held in Canon’s collection in Japan, and is seen here with a Nikkor 5cm f/2.8 lens. This combination would have cost ¥480, including a case. The cheapest variant was the S with a 5cm f/4.5 Nikkor at ¥335, while the f/3.5 Nikkor added ¥55. Specifying the F2 Nikkor took the price up to a heady ¥550 (equivalent to about $125 if converted into American dollars at that time).COURTESY CANON CORPORATION

One of the first Hansa Canons with a 5cm f/3.5 Nikkor lens.COURTESY JCII CAMERA MUSEUM, TOKYO

An even faster 5cm f/1.5 had also been developed by January 1939, along with a coated 3.5cm f/3.5 wide-angle lens (all Nikkors were coated from 1939 onwards using a technique involving chemicals applied in a vacuum, perfected in the USA a couple of years earlier), but the Second World War interrupted civilian production. In fact, Japan had been at war with China for several years, but war with the USA and its allies would have a massive impact on the daily running of the Nippon Kogaku works.

Uncertain Times

The Japanese Army marched through Manchuria at the end of 1931 and the fighting became increasingly fierce as they pushed towards Shanghai at the start of the following year. Naturally the military’s suppliers, Nippon Kogaku included, had full order books for specialist equipment (such as rangefinders, binoculars and aerial cameras, plus a batch of 300cm f/20 long-range cameras), prompting a massive expansion programme at Oimachi, including the building still in use at Nishi-Oi.

The conflict continued even after Manchuria was declared an independent state in February 1932, leading to castigation by the League of Nations. Japan eventually withdrew from the Assembly and the nationalistic government in Tokyo ordered the Imperial Army to take city after city until a truce was signed in May 1933, neutralizing a huge part of northern China. Still the push continued, this time to create a buffer zone between Manchuria and central China. Events came to a head in 1937 when Japan took Peking.

Hand-held binoculars were produced for both general use and the armed forces, although after the conflict in Manchuria only military orders were catered for. Popular pre-Second World War models included the Atom, Novar, Orion, Bright, Luscar and Mikron. This picture shows the Novar 7 × 50 version.

The Type 96 aerial camera from the mid-1930s. This is classed as a hand-held camera, with an 18cm lens and cabinet frame size, although there was a smaller Type 99 version that ultimately used a 7.5cm lens and standard Leica (36 × 24mm) film.

Long-range 25cm binoculars for military use. This particular type was introduced in 1936 and can be seen here with its lens covers in place.

A large floating telescope completed in 1939 to check the rotation of the Earth on its axis. It was in service at the Iwate National Observatory until 1987.

One of the 15m rangefinders built for the flagships of the Imperial Navy.

A view of the legendary battleship Yamato, pictured in 1941, and equipped with Nippon Kogaku rangefinders and other optical equipment.COURTESY US NAVAL ARCHIVE

A Type 94 range plotter to intercept the path of enemy aircraft. This extremely complicated machine was operated by seven people. Eighty-one plotters were completed between May 1937 and the end of the war.

In the background the Japanese Navy was flexing its muscles, planning the fearsome battleships Musashi and Yamato. Tsurayuki Yagi, later Nippon Kogaku’s Vice-President, was dispatched by the naval authorities to Germany, where he stayed for almost three years in the early 1930s. During his stay he liaised with Carl Zeiss to learn as much as possible about large optics, in readiness for the domestic design and production of stereo-type, long-range rangefinders required for the new ships. The 15m Nippon Kogaku rangefinders that resulted were so advanced and accurate that it has often been said that not even Zeiss could have made them at that time.

Interestingly, Japan’s thirst for acquiring European technology was never stronger than it was during this period. Researching for different projects, the author has come across a number of instances when Japanese attachés spent a great deal of time in German factories. A Nissan representative, for example, stayed several months with the Porsche family during the first years of the Volkswagen project. Indeed, the gentleman even secured blueprints of the VW, but, because the deal never evolved into an obvious link at the Japanese end, it remained previously unrecorded. Stories like this are quite common in various leading industrial companies.

After remaining neutral for some time regarding the situation in Manchuria, America spoke out in October 1937, calling Japan an invader. The USA finally put a trade embargo on Japan just before war broke out in Europe, having a drastic effect on the Japanese silk industry, one of the country’s most lucrative exports. The situation was made all the worse by a bad season for the farming community, inclement weather putting many out of business overnight after losing a crucial harvest.

Nippon Kogaku, however, was booming on the back of military orders, doubling its normal annual income in 1938, by which time it had a satellite factory in Manchuria (christened Manshu Kogaku), built at the request of the government. Firmly established as the country’s leading supplier of optical equipment – well ahead of the other big makers, such as Tokyo Kogaku (Topcon), Chiyoda Kogaku (Minolta), Takachiho Kogaku (Olympus), Konica, Fujifilm and Hoya, in terms of production volume – it was often difficult to keep up with demand at home and even more factory space had to be secured.

Meanwhile the situation in Europe was becoming increasingly tense: there was civil war in Spain, and the rise of the pact between Hitler, Mussolini and Stalin threatened to bring an end to an uneasy peace that had existed for two decades. Japan aligned itself with Germany as the so-called ‘phony war’ in 1939 quickly escalated into a very real one, and Europe was plunged into a full-scale world war once more.

Second World War

Nippon Kogaku again proved invaluable to Japan’s military campaign. In 1940 the company had a workforce of 7,585 people. By 1943, led by President Yoshio Hatano, it had increased to almost 16,000; by the end of the conflict it boasted a total of more than 25,000 workers and no fewer than twenty-six manufacturing facilities, including twelve shadow factories.

The Nippon Kogaku Kawasaki works, started in late 1938 but not completed until 1940. One can sense the feeling of national pride prevalent at the time.

Most people know of the devastation caused by the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but few realize the level of bombing suffered by Tokyo. The capital city was hit hard on numerous occasions, with firebombs ripping through the predominantly wooden buildings (even today, most houses are built in wood, as they are better able to withstand earthquakes), hence the need for shadow factories outside Tokyo to augment the existing plants.

A Nippon Kogaku share certificate issued in October 1941. During the war years the company made enormous profits, although 1945 brought about a complete reversal of its fortunes.

While the budget and time for most research and development projects were cut to zero, at least the company’s technicians were kept busy in their quest for superior materials, 100 per cent reliability and weight reduction, and they were able to continue their work on rangefinders and lenses for aerial photography. Nippon Kogaku also inherited production orders from other companies. A large aerial camera was being made by an outside concern, but the military authorities issued a command stating that Nippon Kogaku should take over production in 1944 to ensure quality. This was a fascinating camera, with automatic operation, a motor drive and a 50cm f/5.6 lens. Around 600 were built at the Kawasaki factory before the end of the war.

With fighter aircraft evolving rapidly, firing sights had to keep up with them. Lightweight, accurate sights were a must, and for testing purposes Nippon Kogaku had its own aeroplane called ‘Nikko-Go’ kept at Haneda Airport from 1937 onwards.

The Nishi-Oi works photographed in 1945, with Kogaku Dori (or Optical Road) running past it. These buildings are still in use today, surrounded by more modern facilities.

Before the end of the war Nippon Kogaku had been involved with literally dozens of interesting projects, including the development of night vision equipment (‘Nocto-Vision’), specialist gun sights (including the use of infrared light), a 1.6cm fisheye weather observation camera lens, measuring equipment, and even underwater motion detectors. By 1945 Nippon Kogaku was, without doubt, one of the world’s leading technical innovators, but in September Japan’s industry was thrown into turmoil following the country’s unconditional surrender aboard the USS Missouri.

Rising from the Ashes

Having had its production facilities, and even design drawings and research data, for anything remotely linked to the military taken away, this once flourishing concern, which had posted record profits in 1944, was reduced to just 1,700 workers at its main plant in today’s Nishi-Oi, plus, for a short time at least, a small shadow factory in Shiojiri, Nagano, a long way to the west of Tokyo.

As with so many Japanese companies, General Douglas MacArthur (as Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, or SCAP) quickly expunged all the power vested in Nippon Kogaku by breaking up the big zaibatsu that controlled them. On VJ Day Mitsubishi Heavy Industries was the firm’s main shareholder, with around 145,000 shares, while another arm of the Mitsubishi empire owned 22,000, a little less than Asahi Glass, the only other major stockholder at that time.

It was in 1921 that Crown Prince Hirohito became Japan’s Regent, as his father was gravely ill. Emperor Taisho died on 25 December 1926, when Hirohito’s troubled ‘Showa’ reign began. Often blamed for the war, in his defence Hirohito rightly pointed out: ‘The Emperor cannot on his own volition interfere or intervene in the jurisdiction for which the ministers of state are responsible. I have no choice but to approve it whether I desire it or not.’ Here the Emperor is seen addressing his loyal subjects (including the author’s grandmother) during a 1947 tour of the country. In his free time he was often seen crouched over a Nippon Kogaku microscope or another piece of scientific equipment produced by the company.

POST-WAR LENS MAKING

After being checked for quality, the glass is cut and ground into the rough size required for the lens. It is then put on a curve-generating machine, and made smooth with a finer sand compound before being polished by experienced artisans. Once perfect, lenses are glued together to produce the correct number of elements and groups, and then the lens is centred and matched to a barrel. Following coating and quality control tests, it is finally dressed with its metal components before being tested once more and released to the dispatch department. All lenses were produced and tested alongside each other, as seen in the final shot of a large format 45cm f/9 Apo-Nikkor lens receiving its anti-reflection coating in a glass bell jar; the Apo-Nikkor line was often used in the film industry or for photo-engraving.

A meeting was convened in Tokyo on 16 August 1945 to consider the options available, but the future looked gloomy for a company that received most of its income from military orders. To keep the business going, albeit on a small scale, having lost so much factory space and around 23,000 workers (if one includes the 4,000 or so that had joined the armed forces during the conflict), Hatano declared that Nippon Kogaku should remain in the optics business. At another meeting held on 1 September it was decided that the company would aim to produce seventy-three different lines of optical equipment in fifteen categories that could be used in civilian applications, including such things as measuring and surveying instruments, eyeglasses, binoculars, opera glasses, telescopes, microscopes and projector lenses. The most important items on the list were without doubt the proposal to market a camera and the reintroduction of its pre-war camera lenses.

Interestingly, several technicians who had reluctantly been made redundant by Nippon Kogaku set up their own lens-making businesses, which goes a long way towards explaining the proliferation of small lens companies in post-war Japan. Few Japanese, however, were in a position to afford such luxuries. Most people, even wealthy individuals in the upper classes, had lost everything in the relentless bombing of the capital, and those that managed to escape this misfortune had much of their assets stripped once the air raids stopped and MacArthur and his men moved into town.

Production at the short-lived Shiojiri plant. GHQ soon put an end to its work on rangefinders, meaning it had to concentrate on surveying equipment and microscopes. The plant closed its doors for good in August 1950.

The Pro-Nikkor movie projector lens proved very popular just after the war. Studio camera lenses, some being developed before the conflict, were also produced.

Based on the wartime Tessar 38cm f/8 design, the Apochromat lens design was duly refined into the 38cm f/9 Apo-Nikkor. In 1949 Japan’s first Apochromat lenses, available in 30, 45 and 60cm sizes, were put on the market, effectively putting an end to the import of German and British versions. All optical calculations had to be done by hand at this time (no fewer than 100 people were employed to double check the mathematics!), and the development of each design sometimes took up to three years to complete.

By 20 September Nippon Kogaku’s production committee had dropped plans for a camera body. While lenses and rangefinders for miniature cameras were approved, it was felt that the Japanese market was not yet ready for an expensive product, and to sell a cheap camera bearing the Nippon Kogaku name would be bad for the company’s enviable image.

Having made sure that Nippon Kogaku had a new direction to follow, Yoshio Hatano stepped down from office in May 1946. The new President was Hideo Araki, but Araki’s reign was to be short. In January 1947 it was announced that Masao Nagaoka, shown here, was to head the company. Nagaoka remained in the President’s office until May 1959, when he was appointed Chairman.

A typical Nippon Kogaku microscope from the early post-war years.

Nippon Kogaku found a ready market for its Mikron 6 × 15 binoculars. Note the ‘Made In Occupied Japan’ marking stamped underneath the company logo.

Nikkor 8mm cine camera lenses were ordered by the American Revere concern in 1949. Between January 1950 and September 1953 a total of 84,000 lenses in three different sizes were supplied. After 1955, 16mm cine lenses were made available.

A Japanese Elmo 8mm cine camera with early and late versions of the D-mount 13mm Cine-Nikkor lens; early types were marked ‘INF’, whereas later lenses had an infinity symbol and a ‘Nippon Kogaku Japan’ marking added to the front ring at the same time. The 1955 Elmo 8-AA was a development of the 8-A of 1940 vintage, itself based on a Bell & Howell camera. The box and lens case belong to a 38mm Cine-Nikkor.

The Regno-Nikkor series was for photographing X-rays using 6 × 6 film.

Telescopes were made in large quantities after the war. This particular device, however, is called a coronagraph, allowing a perfect view of a total eclipse of the sun. It was ordered for the Tokyo Observatory.

Notwithstanding, at a Board meeting held in October 1945 (the month in which General Headquarters gave its approval for civilian production to commence), the management at Nippon Kogaku decided that, in order to survive, it would look into developing its own camera to sell alongside its respected Nikkor lenses; just like the first post-war cars, the earliest lenses and camera equipment made available following the cessation of hostilities were basically pre-war designs that were duly dusted off and reintroduced.

With a new executive committee, albeit still led by Hatano, and a glimmer of hope for the future, during the spring of 1946 a 6 × 6 TLR (twin lens reflex) camera was designed for 120 film, based on the famous Rolleiflex series (one was purchased, dismantled and examined to provide inspiration), along with a 35mm rangefinder model with a focal plane shutter. The TLR design was dropped a few months later (as it had been in a Nippon Kogaku aerial camera application some years before), since the Prontor-type shutter was not up to the reliability standards required by the Nippon Kogaku engineers, while a Compur version would have cost too much to tool up for. The RF camera, however, was considered worthy of further development, unwittingly sowing the seeds for the Nikon brand.

The design was approved on 15 April 1946 and an order for twenty cameras was placed with the production department in June. These were classed as experimental, but the body numbers issued for identification were later continued on the series production models. Under Masahiko Fuketa the Nikon camera design (nowadays known as the Nikon I) was duly finalized in September 1946; although a wooden mock-up was displayed internally on the company’s twenty-ninth anniversary, it would be another year and a half before it was released to the public.

Meanwhile, Nippon Kogaku generated income through selling expensive goods through Post Exchange (PX) shops attached to GHQ. Many components were left over from wartime production, allowing items like binoculars to be built up and sold quickly. Against the odds, being without the support of the military or the Mitsubishi zaibatsu thanks to the GHQ directive, the newly streamlined company was doing reasonably well financially, at least until Japan started to suffer from the ill effects of high inflation a couple of years after the war ended.

The blueprints for the 6 × 6 TLR Nikoflex camera, with its 80mm f/3.5 lens. Giving twelve frames on 2.25in square negative film, it resembled the famous Rolleiflex, and a number of later Japanese cameras, such as the Ricohflex, the Primoflex from Tokyo Kogaku (later Topcon), the Aires, the Yashica Pigeonflex and Yashicaflex, the Beautyflex, the Walzflex, the Minolta Autocord, the Nikkenflex, the Zenobiaflex and the first Mamiyas.

A Nikkor lens advert from July 1947.

Win Some, Lose Some

The decision for Nippon Kokagu to produce its own camera probably had a lot to do with Canon withdrawing its custom, as the two concerns had long-established links with each other. About 2,550 Nikkor lenses were supplied for the Canon S, JII and SII from December 1945. In fact, Nikon made all of Canon’s lenses up until March 1948. During this time the unusual bayonet fitting of pre-war days, when the Hansa Canon was being produced, had given way to the Leica screw mount when the all-new SII was introduced during 1946. Canon started producing its own lenses in 1947, tending to follow the pattern established by Ernst Leitz. This ended a long-standing business arrangement and sparked off a bitter rivalry that has lasted to this day. It should be noted that these early Canons, whilst very similar to the contemporary Leicas in many respects, were not replicas of the German camera.

Nicca made good use of the fact that it sold its cameras with Nikkor lenses, as can be seen in this 1951 advert. The Nicca brand was gradually phased out after its owners merged with Yashica in the late 1950s.

From July 1951 Nikkor lenses were also supplied to Aires, the makers of a Rolleiflextype camera and a few compact 35mm models. This advert confirms that the Z Type camera employed Nikkor optics mounted on a Seiko shutter, as did the Aires Automat from a couple of years later. Like the Nicca, some Aires models found their way to America, where they were badged as Tower cameras.

Several Leica replicas were produced in Japan in the immediate postwar era, however, the most famous being the highly successful Nicca. Ironically, the Nicca brand was founded in 1940 by technicians originally associated with Hansa Canon. Although originally established to repair and upgrade old Leicas and Canons, the Kogaku Seiki Company, as it was first known, produced a replica Leica during the war and put it on general release as the Nicca (or the Tower Type 3 in the USA). Some Niccas used Chiyoda, or occasionally Canon, optics, but they were usually mated with screw-mount Nikkor lenses (made from April 1946), as the latter already had an excellent reputation. A number of lenses were also supplied to Mamiya.

Nippon Kogaku’s reputation for high quality was justly deserved. In reality, of course, one has to remember that the company grew on the back of pre-war military orders, and quality is always of greater importance than cost when it comes to supplying the armed forces with precision instruments. This also goes a long way towards explaining why Nikon equipment has always been expensive compared to the offerings of many of its contemporary rivals: the use of the best materials and leading-edge technology was bred into the firm’s engineers from its earliest days and, not wishing to be drawn into a price war, this added cost simply has to be passed on. As the old saying goes: ‘Pay your money, and take your choice.’

The author’s Nicca 3-S with a 5cm f/2 Nikkor, pictured here with an antique Kutani sake holder.

The author’s pre-war Leica IIIa with a selection of post-war, screw-mount Nikkors (including a 5cm f/2 normal, a 3.5cm f/3.5 wide-angle and 13.5cm f/3.5 telephoto), and a Nippon Kogaku finder.

The Nikkenflex camera of late 1950 vintage was not related to Nippon Kogaku in any way, although the company name – Nippon Koken Camera Works – and its Nikken lenses, angered the executives and marketing people at Nishi-Oi. The threat of legal action probably explains the rarity of the TLR Nikkenflex, despite its good performance and relatively low price.

CHAPTER TWO

THE RANGEFINDER YEARS

THE NAME NIKOFLEX CAN be seen on the design drawings for the medium-format TLR camera. Other names under consideration for Nippon Kogaku’s first camera included (in alphabetical order): Bentax, Nicca (yet to be used by the people at Kogaku Seiki), Nikka, Nikkorette, Niko, Nikoret, Pannet, and Pentax – the latter being another name that would soon be registered as a Japanese trademark, as the camera produced by the Asahi Kogaku Company changed from being known as the Asahiflex to the Asahi Pentax, and eventually only the Pentax moniker was used.

The first Nikon camera advert, placed in the October 1947 issue of Kouga Monthly. Masahiko Fuketa must have thought this day would never arrive. He once said development of the Nikon I was rather like ‘trying to think of solutions whilst running at full speed.’ Fuketa later became the top field engineer, solving problems experienced by end users, before returning to the design section for the S2.

Nikkorette would have made sense, with Nikkor lenses already having a good image among domestic professionals and well-heeled enthusiasts, but Nikon was the name ultimately chosen by Nippon Kogaku’s executives, as it sounded stronger. The ‘Nikon’ trademark was officially announced in March 1947, by which time it was hoped that Nippon Kogaku would have a product to sell.

Original blueprint for the Nikon 35mm camera.

The very first Nikon camera, now lacking its Habutae rubberized cloth focal plane shutter, which took the technicians so much time to perfect. Produced during the winter of 1947, body 6091 laid the foundations for the Nikon legend.

Prototype body 6094, which has survived the test of time far better than 6091 and features the larger ‘Nikon’ script that was adopted on production models. Very strict quality control measures were enforced from the design stage onwards.

However, due to the perfectionist attitude of Masahiko Fuketa and Nippon Kogaku’s other engineers, who had already decided to accept nothing less than a high-quality product, prototyping did not finish until February 1948, about fourteen months behind schedule. The ‘609’ designation marked on the experimental cameras is thought to represent September 1946 (the completion date of the finished design), so one can see the huge amount of time spent testing and refining the first Nikon, despite the pressure to get the new camera into the marketplace as soon as possible.

Nippon Kogaku was first and foremost an optical company, so the lens was always going to play an unusually important role in the package. While Canon had moved away from the bayonet mount to the M39 screw thread favoured by Leica, Nippon Kogaku decided to adopt the Contaxstyle bayonet mount.

Early promotional paperwork featuring body 6091. Note the lack of a Nippon Kogaku badge on the top plate: only simple script was used on the prototypes, but the familiar triangular trademark overlaid with a lens appeared on all production models.

A Nikon I (body number 609471) mounted with an early 5cm f/2 normal.

The die-cast body’s styling actually resembled the German Contax II, too, but it certainly was not a copy. In fact, it is fair to say the first Nikon brought together the best features of the contemporary Contax and Leica models: the rugged exterior and lens mounting system of the former, and the shutter of the latter for greater simplicity and ease of manufacture. With an RF system notable for its straightforward layout compared to the German cameras, this really was an ideal combination, and played a large part in helping to establish Nikon’s reputation for strength and exceptional reliability in the field.

The first Nikon instruction book was in English, as it was assumed few Japanese would be in a position to buy an expensive camera so soon after the war ended. The assumption was probably correct, but the Nikon’s unique selling point – its frame size – actually worked against it in export markets, and hardly any were sold abroad.

Interestingly, a 32 × 24mm frame size was chosen to give the Nikon its own unique selling point. The frame composition was nice, and in an era when film was still very expensive, a 32mm width was originally thought to be the ‘golden ratio’, giving an extra four prints for every 36-shot roll without much image loss. The Japanese Ministry of Education accepted this as a regular slide mount size, but the plan backfired, however, when Americans simply rejected this format as it was not suitable for automatic cutting machines.

Indeed, very few Nikon Is were exported anywhere, as the 32 × 24mm frame size was not compatible with regular slide mounts outside Japan. More than fifty units went to Hong Kong and a handful were sent to Singapore, the USA and Europe, but it was obvious that Nippon Kogaku needed to change to a bigger frame size if it was to break into the lucrative export business on which the management was pinning the company’s future. After all, as GHQ was quick to recognize, the domestic market was still very small in the immediate post-war years, and exports were seen as the main source of sales.

Anyway, the first prototype (body 6091) was used in several adverts that began to appear after October 1947, although production models had a heavier ‘Nikon’ logo above the lens, and the simple ‘Nippon Kogaku Tokyo’ script was replaced by the company’s triangular trademark on the top plate. There were other minor differences, too, but it was a fair representation of what could be bought, assuming one had the money.

The Nikon I had a ‘chrome’ body trimmed with hard-wearing black leather, embossed to resemble lizard skin, although at least one is known to have been produced with a completely black body. Black was favoured by photo-journalists, especially those working in war zones, and so several were made to special order as the years passed. More and more requests for black bodies were received, not only from professional photographers, but normal enthusiasts, too. This ultimately led to chrome and black body options being listed in the catalogue, officially starting with the introduction of the S2 and being offered on almost every Nikon thereafter until the 1980s.

A 5cm lens was included in the price; some adverts mention the f/3.5 Nikkor, which had gained a new, larger barrel in June 1948, but it was usually the faster and significantly more modern looking, collapsible mount f/2 that was supplied as standard fare. An f/1.5 version was also listed in early paperwork, but did not become available until the start of 1950. Other lenses initially included the rigid mount 3.5cm f/3.5 wide-angle and 13.5cm f/4 telephoto, although neither was actually sold until several months after the camera body made its debut. Like the camera baseplate, these early lenses were marked ‘Made In Occupied Japan’, a sign of the times following the 1945 Armistice.

The first twenty prototypes were duly numbered 6091 through to 60920, and one further prototype (60921) was produced before sales of the Nikon I started in March 1948 (with body number 60922 being the first Nikon camera released to the public). Numbers were issued consecutively thereafter, although the Nikon I was to be short lived, production ending after 758 units (including the twenty-one prototypes) had been built, with the debut of the M model only eighteen months later.

A Nikon I on display at the JCII Camera Museum in central Tokyo. Note the collapsible lens on this early model, body number 609387, complete with its elegant lens cap.COURTESY JCII CAMERA MUSEUM, TOKYO