4,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Steeger Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

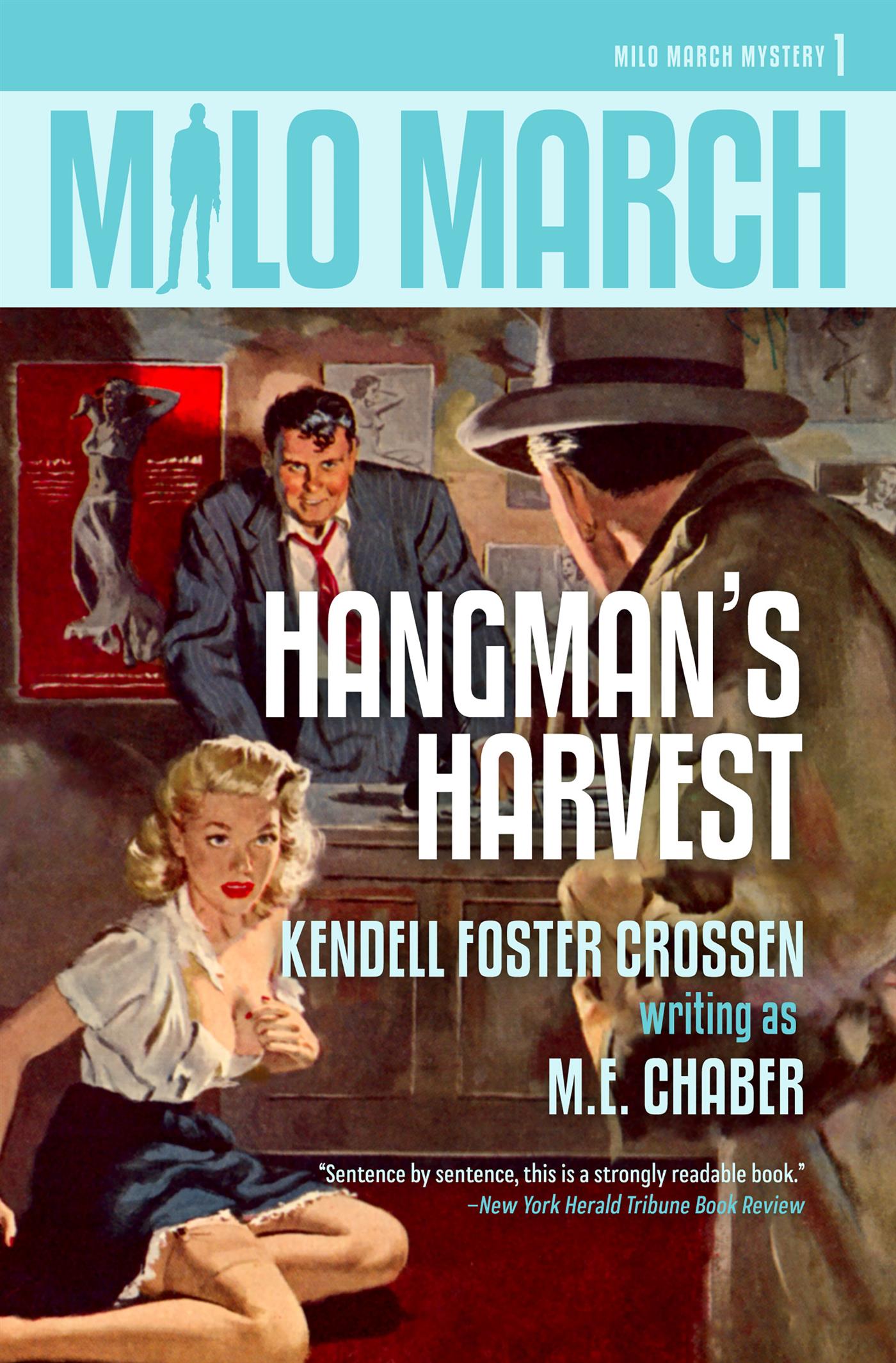

Milo March, a tough private eye from Denver, is sent to Aragon City (which could be Hollywood) to help the City Betterment Committee wipe out the gangsters and hoodlums controlling brothels, bookies, gamblers, shady nightclubs, and the dope traffic. He just has to uncover “Mr. X,” the mystery man who’s been raking in a tidy little income by providing protection to the Syndicate. But can Milo accomplish that without stumbling over something even more dangerous—like who pays Mr. X, and why? Milo is well equipped for the job. He has plenty of gall, good looks, an unlimited expense account, a fishtail Cadillac, and ample experience with lawbreakers—and beautiful, willing women, of whom there are several, but only one who is the girl next door. As March starts his snooping, he is surprised to discover a sexy, naked blonde in his hotel room. And there are other, more painful things complicating his life—things like beatings and fistfights and gun battles, and a blow he never saw coming.

“Sentence by sentence, this is a strongly readable book.” —New York Herald Tribune Book Review

“The established pattern of California coast crime—political graft, dope, and prostitution—with a fall guy introduced to clean it up. Milo March, hired by the Civic Betterment Committee, fouls up with the brains and muscle men when he spies on his assignment before he is due, latches onto cultured hoods and tough racket boys—and pays off from syndicate roughing up to cards down.” —Kirkus Reviews

“It was obvious that sooner or later there’d be a capable challenger of Mickey Spillane in the concoction of the muscular and seductive mixture that makes Spillane’s best-selling books. A challenger has appeared in M.E. Chaber.” ―Los Angeles Examiner

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Hangman's Harvest

by

Kendell Foster Crossen

Writing as M.E. Chaber

With a Foreword by Kendra Crossen Burroughs

Steeger Books / 2020

Copyright Information

Published by Steeger Books

Visit steegerbooks.com for more books like this.

© 2020 by Kendra Crossen Burroughs

The unabridged novel has been lightly copyedited by Kendra Crossen Burroughs.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without permission in writing from the publisher. The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law.

Publishing History

Hardcover

New York: Henry Holt & Co. (Holt Mystery), February 1952.

Toronto: Clarke, Irwin & Co., 1952.

Paperback

New York: Popular Library #482, as Don’t Get Caught, 1953.

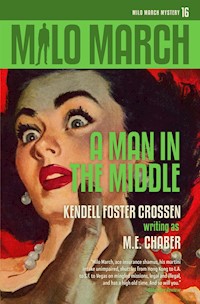

New York: Paperback Library (63-507), A Milo March Mystery, #16, January 1971. Cover by Robert McGinnis.

Dedication

For Martha

Foreword

The Milo March Mysteries

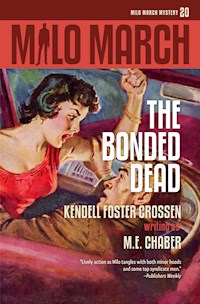

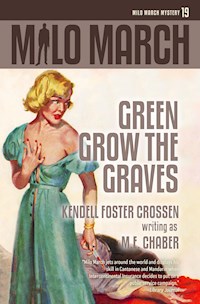

Milo is back! As one of the children of Kendell Foster Crossen, I am pleased to introduce this series of twenty-two Milo March mysteries, which he wrote under the name M.E. Chaber between 1952 and 1975. The final novel in the Steeger Books series, Death to the Brides, is being published for the first time, and the last volume—#23, The Twisted Trap—consists of six magazine stories collected for the first time.

Milo March still has many fans, especially those who remember the Paperback Library series with the sensational Robert McGinnis cover art—more about that later. I hope Milo also attracts younger fans of vintage entertainment that is both quaint and current.

Then or now, the sources of angst are familiar—cold and hot wars, political assassination, dictators, corruption, organized crime, racial conflicts, disappeared people. But it’s a source of amusement to be reminded that we are in Milo’s era: Ducking into drugstore booths to make calls on dial phones. Placing a long-distance call with an operator, who then listens in. Calling single women “Miss.” You can pack a gun in your airline luggage, and someone comes around selling cigarettes to hospital patients in bed. Milo’s cases involve vast amounts of money—who wants to be a millionaire? After consulting an online inflation calculator, I remind myself that in today’s money a mere million translates to over eight million green ones.

Milo may have been a gleam in his creator’s eye for a dozen years since Ken Crossen began his full-time writing career in late 1939. In the 1940s he published some forty-five pulp detective and murder mystery short stories and novellas. During that time he was also writing scripts for radio mystery shows and publishing magazines and comic books—notably The Green Lama, based on his pulp character in Double Detective magazine.

Ken told an interviewer that restlessness, along with frustration with the unsuccessful publishing business, drove him to write his first novel intended for hardcover publication: “I worked out the character of Milo March, making him an insurance investigator since that was something I knew very well. I was to some degree influenced by Hemingway and Hammett, but added more of a dash of humor and more throwaway lines. Partly as a result of this, a later reviewer said that I wrote ‘soft-boiled’ novels.”

Crossen had worked as an insurance investigator in Cleveland—which doesn’t sound terribly exciting, but it may have sparked his imagination—and his first insurance investigator story, “Homicide on the Hook” (1939), featured a detective named Paul Anthony. “The Jelly Roll Heist” was the first Milo March magazine story (published August 1952 in Popular Detective), but Milo’s print debut was the novel Hangman’s Harvest, first published in February 1952 in hardcover.

In Hangman’s Harvest (1952), Milo March is a private eye employed in Denver but hired by a group of citizens in Southern California to solve a case of corruption in their city government. This story is not even about insurance investigation! But from the very beginning, it was the character of Milo that was the centerpiece. Milo in fact plays several roles in the series, including busting international crime syndicates and taking on dangerous espionage assignments as well as solving disappearances, murder mysteries, and jewel robberies.

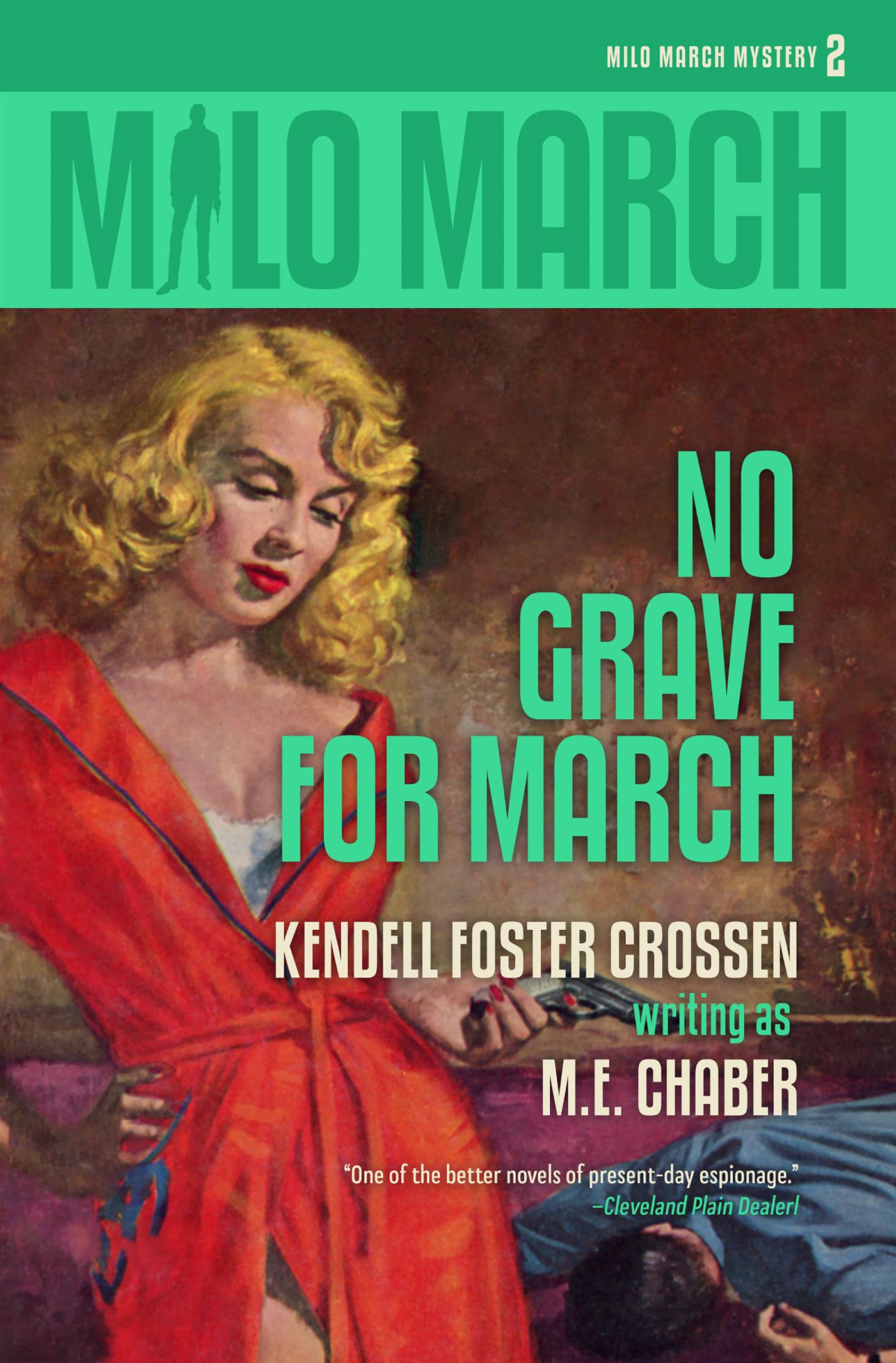

The second Milo March book is a Cold War spy novel set in East Germany, No Grave for March (1953). Milo happens to have been an OSS officer during World War II in Europe, and he is recalled to do special missions for the CIA in five of the novels and one of the short stories.

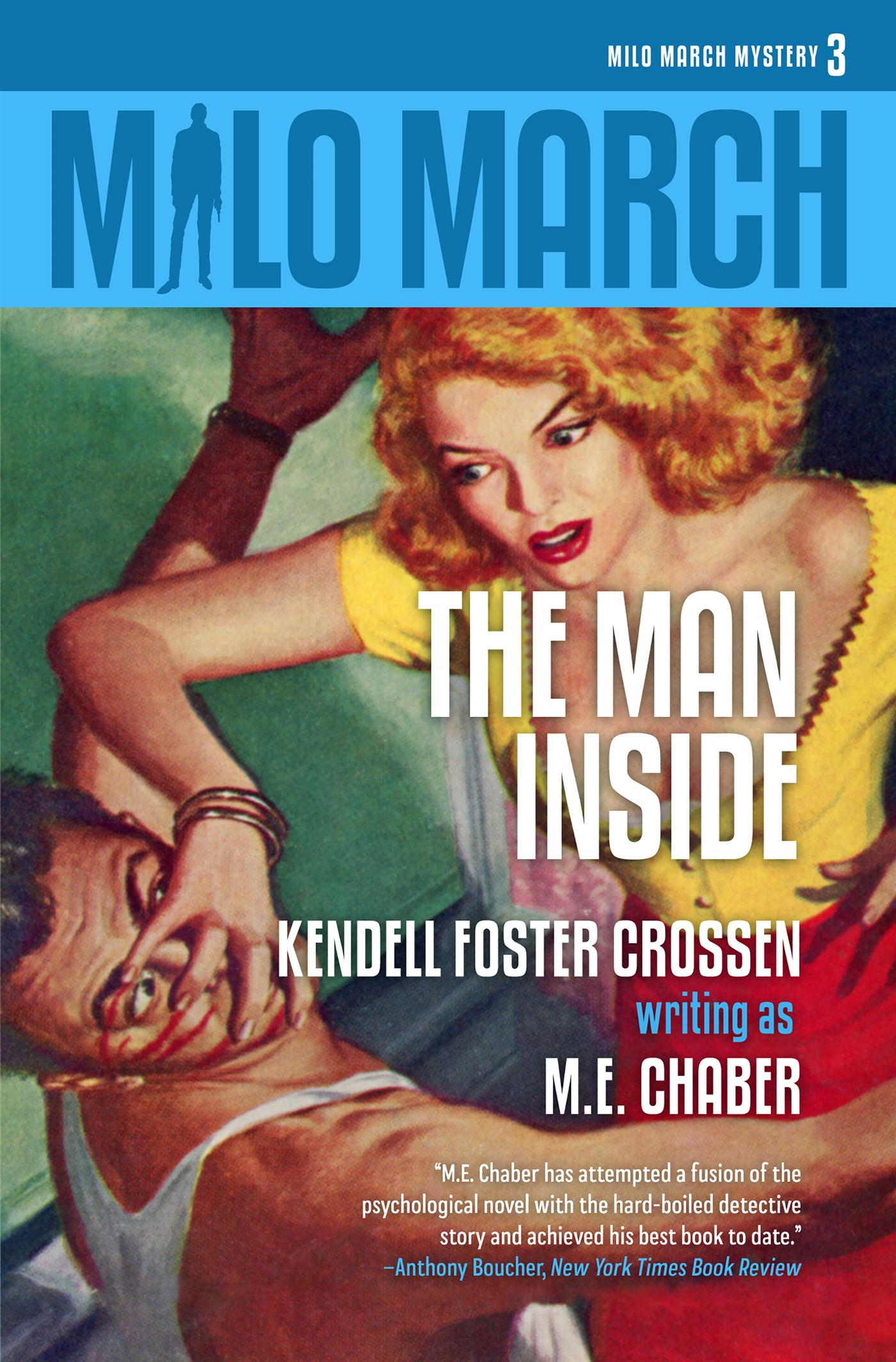

It is not until The Man Inside (1954) that Milo investigates an insurance case—the theft of an immense blue diamond—in a story of psychological suspense. Though still based in Denver, Milo hops continents in pursuit of the obsessed thief, who has assumed a false identity in Spain.

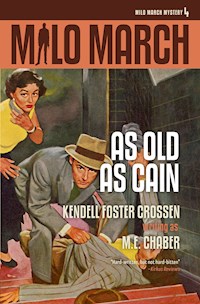

He’s in Ohio in #4, As Old as Cain, then he’s a CIA operative again in The Splintered Man (1955), based partially on true events and featuring the use of LSD as a weapon of mind control. That story takes place in East and West Berlin and Moscow. Denver, it turns out, is the actual scene of action only in three magazine stories of 1952–1953.

Milo moves from Denver to New York City in A Lonely Walk (1956), to set up his own insurance detective agency on Madison Avenue, the buckle on the Martini Belt. The sign on his office door is freshly painted and will provide the opening theme for several books: “I’m Milo March. Insurance investigator. At least that’s what it says on the door to my office.” There is no time for an identity crisis, as Milo is almost immediately sent to Rome on an insurance case involving murder (based on a real-life case) and government corruption.

Our hero continues to zip around the world, alighting in Rio de Janeiro, the Caribbean, Lisbon, Madrid, Paris, Stockholm, Hong Kong, Hanoi, and Cape Town, South Africa, with those few sneaks behind the Iron Curtain—all giving Milo a chance to show off his multilingual gifts. He speaks both Mandarin and Cantonese, and can even pass as a native speaker in German, Russian, and Spanish. His exploits stateside take him to New Orleans, Miami, Las Vegas and Reno, San Francisco and L.A. Both small-town Ohio and Greenwich Village, New York, were homes to Ken Crossen, and his alter ego, Milo March, knows his way around them, too.

Milo March is assumed to be “tall, dark, and handsome,” perhaps because of the famed McGinnis paperback covers, which feature a James Coburn lookalike. When asked what actor he would have liked to see portray March, Crossen named the late Humphrey Bogart.

Robert McGinnis, in creating art for the Paperback Library reissues of 1970–1971, chose the distinctive-looking actor James Coburn as his model for Milo. Readers have asked whether Coburn actually posed for McGinnis, or whether Coburn even knew that his image was used. The answer is revealed by Art Scott in The Paperback Covers of Robert McGinnis: “The reason why the fictional detective Milo March on covers of Paperback Library’s ‘Milo March’ series looks like James Coburn is because the artist, Robert McGinnis, had some photos of Coburn he’d used previously to help him paint posters for Coburn’s movies. He modeled March on these photos. To quote McGinnis, ‘Coburn was easy to draw—long and lean, ideally proportioned, with a lot of character in his face.’ ” In addition, Art Scott reported in The Art of Robert E. McGinnis that the painter anxiously expected a call from Coburn expressing his objections, but it apparently never came.

In the 1953 story “Hair the Color of Blood,” Milo’s ID shows that at age thirty-five he is six feet tall, 185 pounds. (For the record, Bogart was five foot eight, Coburn six foot two.) Milo is not especially athletic (“I’ve taken a vow to never swim in anything deeper than a brandy and soda”). In The Splintered Man he says he “galloped past the middle thirties, getting a couple of inches thicker in the middle.” When a woman says to him, “Did anyone ever tell you that you’re a beautiful hunk of man?” he replies: “Usually they just tell me I’m a big hunk.” All the ladies who cross his path find Milo irresistible. One reviewer called this unrealistic, but that’s silly. Escapist literature exists for the sake of fun, and this fills the bill.

I wonder, if books were rated like movies, how would the Milo March books fare? In general I feel that anyone who’s heard of birds, bees, and bullets can enjoy these books.

Language: Men speak in “short, Hemingway-type words.” (That’s what Milo says instead of repeating the actual words.) Or: “He told me what I could do to myself. It wasn’t very polite, so I ignored it. Never take advice from strangers.” Some lines exchanged by Milo and his mobster enemies are strangely juvenile (“Go play dead”). Only once, a character exclaims, “Shit!”

Substance abuse: Steve Lewis, in reviewing a Milo March book, wrote that “if you cut out the references to drinking, the book would be at least 20 pages shorter.” Milo’s drinking does seem to increase as the series advances. Social disapproval of alcoholism is obviously greater today than it was fifty-odd years ago. The recovery movement took off in the 1980s, after Ken Crossen’s death. Milo says, “Many people complain that I drink a lot. I do, but I also do the things that have to be done.” Throughout the series, every drink that is poured, every tinkle of ice cubes against glass, is recorded. But Milo never gets drunk—except on vodka in stories where he has assumed a Russian identity.

Violence: In several books, Milo gets a rough beating or takes a bullet, but he himself does not have a violent nature. I like what Mike Grost writes:

Milo March stories differ radically in tone from those of Raymond Chandler. Chandler’s stories are dark, and they depict a world full of evil characters. Crossen despises mobsters and crooks, but basically he likes 1950’s America and the world in general. Neither he nor March seem alienated, which is the word I’d use to describe Philip Marlowe and his successors. Instead, Crossen and March preserve a sunny, good-natured attitude towards most of life. Indeed, Crossen’s tone is generally comic throughout. Even his mob villains have a slightly tongue in cheek quality. Parts of the story even approach the comedy of manners, something one associates more with Golden Age sleuths than 1950’s private eyes. Milo March also has a different attitude towards the men he meets than most private eyes. Usually he winds up making friends with them, and the book is full of scenes of male bonding.

Milo uses his fists to great effect. He arms himself with one or two guns but will not kill men if shooting their kneecaps is enough. He’s killed a couple of weasel-faced hoods who were pointing weapons at him, and in one case he didn’t tell the cops about it.

Someone wrote that “M.E. Chaber has been called the originator of a new genre, the ‘soft-boiled’ suspense story, in which the emphasis is on believability of character and situation—and not a single blonde, brunette, or redhead is shot or kicked in the stomach.”

Sex: Milo loves women, booze, and food, more or less in that order. He responds to a come-hither look and has chemistry with a certain type of woman, but he leaves the strictly-for-keeps girls alone. He expresses a preference for short, shapely brunettes, and in The Gallows Garden he even recites a medieval Spanish poem in praise of short women to a petite assassin who is aiming a pastel blue pistol at him. Nonetheless, his favorite lover is a tall lady pirate from Hong Kong. Women’s bodies are relished—their cleavage viewed from above, and the view from the rear as they walk away, as long as they are not wearing a girdle—but details are jauntily left to the imagination: “She wore a print dress that looked as if it had been dropped into place from a tall building as she passed beneath. In a high wind.” In So Dead the Rose, one of my favorites, the sight of the naked breasts of an unconscious enemy agent humanizes Milo in the midst of an otherwise cold-blooded maneuver.

After a passionate kiss, Milo often picks the woman up and carries her into the bedroom—then fade to black. “We had another drink, then I took her by the hand and led her into the bedroom. We both knew about the microphone, but after a while we forgot about it.”

Nudity: In Wanted: Dead Men a Swedish blonde enjoys dining naked at home and urges Milo to disrobe (“You may feel silly sitting around and having a drink with your clothes off, but not as silly as you do sitting there fully dressed across from a nude broad”). Women are nude in several books … but duh, you can’t see them. The imagination gets good exercise in these fast-paced narratives.

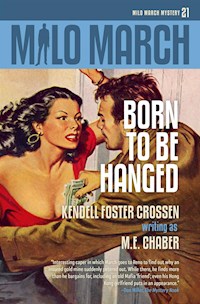

Prejudice: There are a few outdated, derisive references to gay men (“Stay home and nurse your wrist before it becomes too limp to use a gun”). I considered editing some minor ones out but felt it wouldn’t be honest. To insult a man by calling him “Percival” is more comic than offensive. Yet in Born to Be Hanged, Milo is a kind friend to two older men who have lived together for years; the relationship is suggestive of a marriage, a surprisingly prescient touch for a 1973 book. Milo befriends African-Americans in A Hearse of a Different Color (1958) and The Flaming Man (1969). In both novels there is a black character who hides behind stereotypical mannerisms, but Milo treats him as the intelligent human being that he is. Ken Crossen told me he created these characters deliberately, wanting to add some moral depth to these works of genre fiction.

I was slightly annoyed by the repeated Italian hood stereotype. In A Man in the Middle (1967), I altered the phrase “a face like a dark-complected weasel.” (I left the weasel part in.) From Six Who Ran (1964), I deleted this sentence about a Brazilian cabbie: “His skin was so dark that I suspected it indicated an Indian ancestor somewhere.” Call me P.C., but I don’t know what it was supposed to imply and it seemed superfluous.

Ken Crossen remained with the same publishing company for all of the published Milo March books, and I imagined his editors would keep track of previous books in the series, taking note of characters who appeared in more than one book and ensuring consistency of details. To my disappointment, this was not the case, and I decided to copyedit all of the books, since I am a professional book editor. I also added some footnotes, chiefly about dated references and verse in foreign languages. It’s a nerdy touch that may be helpful to some readers.

My editing rarely required changes to the actual wording and was mostly concerned with consistency of style. However, in several books I did a bit more than that. For example, in Born to Be Hanged, the final book published in Crossen’s lifetime—which is #21 in the series—a character from #18 is mentioned. He is called Gino Mancetti in #21, and it is noted that he was involved in a prior case, which is very clearly the one from #18, The Flaming Man. But in #18, the character’s name is Gino Benetto.

If only it were just a matter of changing “Mancetti” to “Benetto.” The problem is that Milo shot Gino Benetto in both knees in #18. A cop remarked that Benetto would probably never walk again. Yet in #21, there is no sign of Mancetti’s having any infirmity, and the fact that Milo ever shot him is not mentioned when they meet.

So I changed “Gino Mancetti” in #21 to “Dino Mancetti,” to make him different from “Gino Benetto” in #18. And I made it less specific about where Milo knows him from.

Finally, in the last novel, #22, Death to the Brides, Crossen inserted a character from another series, Major Kim Locke of the CIA, briefly into the plot. Kim is lending his military service dog, Dante, to Milo for a mission in Vietnam. I had to change the breed of the dog, as I explain in the afterword to that book. If this were the same Dante that had been Major Locke’s dog in 1953, that heroic canine would have gone to his reward by 1975. The other problem is that Dante was a Hungarian Puli (a breed that lives to about age sixteen), which has fur in long dreds. The breed is too heavy and hairy to be carried through the Vietnamese jungle, which is what Milo does with Dante in #22.

After conferring with the science fiction author Richard Lupoff, who helped me edit Death to the Brides, I changed the dog to a miniature pinscher, named Dante after his predecessor. (I learned that the US military does utilize miniature breeds for certain missions.) Although Ken Crossen had several favorite poets, I didn’t want to take the liberty of renaming Dante. (Ken really liked Robert Service, the Bard of the Yukon, but I couldn’t name a service dog Service.)

In real life, Ken Crossen named his own dog Milo.

Kendra Crossen Burroughs

Prologue

Pallida Mors aequo pulsat pede …

Cities are like women. Some are softly rounded and seductive. Some are brazen, with scarlet slashes across their faces. There are cities that are noisy and nagging, and cities that cling to the strong arm. There are cities which are always just out of reach, with hard, defiant little haunches moving with provocation beneath the surface.

Aragon City is like a successful call girl in church on Sunday. She sits primly on the coast of California with her back to the Pacific. To her north is Santa Monica; to her south, Ocean Park. But directly in front of her is Los Angeles, sprawling around Hollywood as though trying to hide it. Los Angeles, a tumorous growth of flat, ugly buildings hiding beneath layers of smog. And within the growth, Hollywood, the city without a charter and with no city limits; Hollywood, with its movie stars and tabernacles, Dianetics and Vedanta, sewing circles and call houses—where pimps represent actors and directors and writers as well as ladies of the evening.

And Aragon City, her fresh and innocent air a gift from the Pacific, sits on the edge of her seat and waits for the services to be over.

It was night in Aragon City and the wind from the ocean was cool. Down near the boardwalk old men sat outside, letting the cold remind them of the east or the west or the north. Above their heads the palm trees waved to each other.

On Vallejo Street, a pale green Cadillac swept into the curb and stopped. The sleek-looking man walked into the apartment house and returned in a few minutes.

“A dozen sticks,” he said to the girl as he slid in behind the wheel. “We’re riding high tonight, baby.”

Two dozen men and women crouched over a green baize table in a club on the ocean front. Their eyes were feverish as they watched the spinning wheel. Their breathing matched the clacking rhythm of the ball.

A hopped-up Ford squealed to a stop in front of a liquor store on Poinsettia. A boy went in and bought six bottles of a famous soft drink.

“There’s a bottle apiece and two extra for you girls,” he said as he came back.

Across the street from the Pollux Club a nervous man chewed on his unlighted cigarette and rubbed his cheek against the stock of a rifle. He watched the door of the club, peering beneath the shadow signboard.

The man who came in on the airliner at the International Airport was early. But he wanted to arrive before he was expected; to wander around and feel the city before it knew he was there. He checked his bags at the airport and took a cab to Aragon City.

He went from bar to bar, from club to club. In each he had one drink. Brandy and water. He drank slowly, watching the faces around him, listening to conversations which had no meaning. He looked for nothing special, but collected the faces and the sounds on his nerve ends.

By midnight the only evidence of the brandies was the warmth under his belt. And he knew Aragon City for what she was. He could feel her lack of roots, the violence that bubbled just beneath the surface. He could feel something within him answering the violence.

He walked into a small, dimly lit club on Portola. He sensed a difference as he walked to the bar. Even before he looked around he knew what he’d see. Everyone there was better dressed than in the bars he’d visited earlier—sleeker, more enameled. The men’s coats were more padded in the shoulders and some were tailored to hide bulges under the arms or in the pockets. Here and there he could spot the ones who came to see, to rub shoulders.

He ordered his drink and became aware of the woman who sat next to him at the bar. Her perfume reached out to tug at his senses. He took a quick look. Evening dress. Plunging neckline. Mink stole. Careful blond hair. Her face was familiar. He searched his memory and found the face staring out from a movie screen. He turned back to his drink.

Later he knew she was examining him. He kept his eyes on his drink, letting her take her time. He didn’t know if he was interested, but if it turned out that he was, he liked women to know what they wanted.

He saw two men in the mirror. One was entering and one was leaving. For a minute they stopped and stared at each other. Nothing was said, but you could feel the tightening all over the room. Low-voiced conversations fell off. The room waited, and then the two men nodded to each other and passed.

He felt the shudder that moved over the woman. In surprise, he looked at her. She stared back at him. There was excitement in her eyes. And something else.

It was after one when he left the club with her. She handed him her car keys and pointed out the convertible. It was starting to rain so he put the top up. In the car she leaned against his shoulder, occasionally calling out directions in a sleepy voice.

It was a small estate in the residential section of Aragon City. There was an electronic beam and the heavy wrought-iron gates automatically swung open and then closed after the car. They left the car beneath the car porch. He unlocked the door with her key and followed her in.

In the modern living room, she tossed her handbag on a chair and turned to him, holding her arms out in drunken gravity.

“Put me to bed,” she said simply. She swayed toward him.

He picked up her limp form and carried her out into the foyer. After a couple of wrong guesses, he found the bedroom. He paused uncertainly, then deposited her on the bed. She sagged back on the cover, her eyes closed.

He dropped to one knee and removed her shoes. He ran his hands up along her silkened legs, beneath the evening gown. There was warm flesh against his fingers as he fumbled with the garter snaps, then he peeled off the skeins of silk. Her body was limp as he lifted it to pull the evening dress over her head. Beneath the dress, she wore only the gossamer garter belt.

He hung the dress in her closet, put the shoes on a shoe rack. The stockings and garter belt he tossed over the back of a chair. He turned to look at her.

He hadn’t switched on a light in the bedroom, and the glow of a distant street lamp slanted through the open Venetian blinds to paint her body with ivory and shadows. He reached down to touch one of her firm breasts, and the nipple nestled against the palm of her hand. He let his breath out slowly and his gaze stroked over the rest of her body. It was a well-cared-for body, a delicate hint of curve between navel and cleft, the legs strong and shapely.

He pulled the covers down beneath her so that she rested on the sheets. She still seemed submerged in a drunken sleep, but he was suddenly aware that her breathing was too deep and rapid. A panel of light was across her face and he saw the quiver of a curled eyelash against her cheek.

Anger stirred within him as he stood up. A moment later, savagely, he turned back toward her.

Outside, the tempo of the storm picked up with a sullen fury. The wind swooped down the street, clattering over garbage can lids, snatching up bits of paper and dispatching them into nowhere; it forced its way up the narrow alleys, thrusting its unappeased strength against the very windows, raged through the city. And then the rains came spurting from the skies. Lightning split the clouds and thunder shook the ground.

Here and there a sleeper stirred uneasily, but the honest citizens of Aragon City slept on, unaware that the storm was ravishing their city.

One

I was due in Aragon City at eight that night. On Flight 324 from Denver. I had another brandy and water in a bar on Third Street and got into a cab. It was a quarter to eight when I got to the International Airport.

The girl at the desk said that Flight 324 was on time. I lit a cigarette and took a quick look around the waiting room. There were a lot of people but nobody who looked like they belonged on a committee. Then the public address system came to life and I knew why.

“Mr. Milo March, there is a telephone call for you in booth three next to the United Airlines counter.”

I grinned and ducked out, taking the underground passage to the gates. The phone call meant that they hadn’t bothered to ask if the plane was in or that they suspected I was there early. Not that it made any difference. But I was still going to make it look like I came in on the right flight.

After a while the big transport lumbered off the strip and wheeled around with one wing pointing at the gates. When the passengers came off, I walked along with them into the waiting room. Just to make it artistic, I looked around as if I were expecting someone to meet me. It was wasted, but it made me feel good.

I didn’t have to wait long. “Mr. Milo March,” the girl’s voice said over the loudspeaker, “there is a telephone call for you in booth three next to the United Airlines counter.”

I walked over to the booth and took the receiver from the hook. “Milo March,” I said.

“Just a minute, sir,” the operator said. I waited.

“Milo March?” a new voice asked. It was a man with a salad voice. Crisp.

“Yeah,” I said and waited some more.

“This is Willis—Chairman of the committee. Did you just get in?”

“Isn’t this when I was due?” I countered. I grinned, remembering the twenty-four hours I’d already spent in Aragon City.

“Of course, of course,” he said hastily. “We were going to meet you, March, but thought better of it. Will you come straight here? The address is three-two-two Loma Vista Boulevard. The third floor.”

“Okay,” I said, and hung up. I reclaimed the stuff I’d checked the night before and went out and got a cab. I gave the driver the address and leaned back in the seat.

I already had an idea what it was going to be like. You get feelings like that some days. This was going to be a job that could be summed up with one word. Messy.

Two weeks before this Willis had gotten in touch with me by long-distance phone. First he’d told me who he was. Linn Willis. Sometimes consulting engineer to the Air Force. Owner of the Willis Aircraft Corporation in Aragon City, California. Owner of the Aragon City News. A big shot. Then he added that he was Chairman of the Aragon City Civic Betterment Committee. I could already smell the next step.

Aragon City was steeped in crime—that was his word, steeped—and they wanted a competent investigator to prepare a report for the Civic Betterment Committee. I had been highly recommended to the committee. They wanted to hire me.

I said no. I said that I already had a job, I liked the job, I was eating regularly, and I didn’t give a damn if the hoods took over Aragon City. He said he hoped I’d think it over and then hung up.