4,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Steeger Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

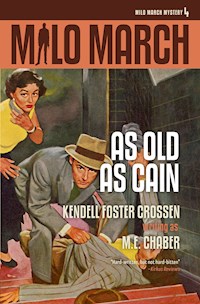

Samson Hercules Carter is a little man with a big name who has fallen obsessively in love with a diamond. The Tavernier Blue is only a little smaller than a golf ball and worth a fortune. To insurance investigator Milo March, the hunk of carbon doesn’t seem as attractive as the equivalent in cash, but he can see why the little man might want to put it in his pocket and take a walk. But the problem is, Carter has also shot a man to death in the process.

The insurance company sends Milo to track down the murderer and recover the stolen diamond—a task made all the more urgent because he’s got competition. Some of the world’s top jewel thieves would also like to get their hands on the diamond, from sinister professionals to a beautiful seductress. In one of Milo’s wildest adventures ever, the chase takes him from New York to Lisbon and Madrid, where the thief, a mild-mannered accountant, has transformed himself into a new identity as a cultured gentleman, an alternate personality that he has secretly developed for years. Getting the thief back to America for prosecution is challenge enough—but where the hell did the little man hide the diamond?

The Man Inside was made into an English film of the same name in 1958, directed by John Gilling and starring Jack Palance and Anita Eckberg.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

The Man Inside

by

Kendell Foster Crossen

Writing as M.E. Chaber

With an Afterword by Kendra Crossen Burroughs

Steeger Books / 2020

Copyright Information

Published by Steeger Books

Visit steegerbooks.com for more books like this.

©1982, 2020 by Kendra Crossen Burroughs

The unabridged novel has been lightly edited by Kendra Crossen Burroughs.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without permission in writing from the publisher. The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law.

Publishing History

Magazine

“The Man Inside,” Bluebook, vol. 98, no. 2 (December 1953). Illustrated by Al Tarter. A condensed version.

Hardcover

New York: Henry Holt & Co. (A Novel of Suspense), February 1954. Dust jacket by Ben Feder, Inc.

Toronto: George J. McLeod, 1954.

London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1955.

Paperback

Popular Library #632, as Now It’s My Turn, 1954. Cover by Ray Johnson.

Popular Library Giant #G282, 1958 reprint. Cover by Ray Johnson.

New York: Paperback Library (63-213), A Milo March Mystery, #4, January 1970. Cover by Robert McGinnis.

Movie

The Man Inside (UK, September 1958). Directed by John Gilling and starring Jack Palance and Anita Ekberg. Screenplay by David Shaw, based on the novel.

Dedication

For Martha

II Samuel 1:26

Interlude 1

The blue diamond lay by itself in the very center of the velvet-covered table. The light flashed from it, changing with every heartbeat. There were times when it seemed filled with blue fire. Other times—and his breath came faster—when it seemed that he could almost see himself in mysterious miniature deep in the flame.

He was hardly aware that a third person had entered the room.

“There’s someone on the phone,” the secretary said. “He won’t speak with anyone else.”

The other man glanced at the diamond, but the gesture was brief and cursory. There was no reason to doubt someone he’d known for fifteen years. He followed the secretary from the room.

He knew when the other man went to answer the telephone, although he didn’t take his eyes from the blue diamond. He had planned on that phone call for five years. It was part of something he had planned for twenty years.

He picked up the diamond. Its surface was cool against his warm flesh. He held it for a second, watching the changing light, then dropped it into his pocket. He turned and left the room. There was no one to see him go.

He had rehearsed it so often in his mind that this time felt no different. Although this time it was real. He could feel the diamond in his pocket. He had known from the first that it belonged to him. It had always been his; now he had taken possession of it. That was all.

He walked slowly down the stairs. Twenty-one steps. Then he pushed open the heavy iron door and stepped out into the corridor. He closed the door behind him, smiling at the detective who stood guarding that door. He took his left hand from his pocket, his finger reluctantly leaving the diamond. He plunged his right hand into a pocket, curling it around the cold metal.

“Leaving early today, Mr. Carter?” the detective said.

“No,” he answered truthfully. “I’m leaving right on time.”

Everything was on time. The phone call had come in right on the second. He’d been right in his estimate of how long it would take Robert Stone to answer the phone. He’d had one second to spare in the time he’d given himself to pocket the diamond and walk down the stairs.

“You’re right,” he corrected himself gravely. “I am one second early.”

The detective laughed.

Here he had allowed himself an extra twenty seconds. He didn’t know about alarms; it might have aroused suspicion to have asked. He couldn’t be sure how long the telephone conversation would last. So he had added the extra twenty seconds.

He stepped through the outer door to the sidewalk, wondering why the detective laughed.

“Wait a minute,” the detective called.

He knew he’d been wise to include that twenty seconds. But it wasn’t much time. Not enough to ask any questions or answer any. He turned and stepped back into the small corridor. He took the gun from his pocket, steadied it, and pulled the trigger. It didn’t sound as loud as he’d expected. He watched curiously as the detective slumped to the floor. He had never seen anyone die before.

He returned the gun to his pocket and stepped back out on the street. He glanced at his watch. He was surprised to see that it hadn’t taken twenty seconds.

He walked briskly to the corner. Nobody noticed him. They never had.

One

Did you ever walk through Skid Row—the Skid Row of any city—and see an old woman, blowsy with fat, passed out with a Tokay smile on her face? Did you ever stop to look at her and wonder what the smile meant? Maybe, you thought, she was dreaming about the time when she was a young chippy. Well, that’s how New York City looks when you fly over her early in the morning—a great, sprawling, old woman of a city. You rub the sleep out of your eyes and look at her with mixed feelings; equal parts of sympathy, sadness, envy, and disgust.

It was Saturday morning. The plane came down at LaGuardia on time. I had slept on the plane the night before, but it hadn’t been enough. I had thefalse sense of well-being that comes from too little sleep.

As I came into the terminal the loudspeaker was blasting: “Mr. Milo March. Will you please go to the Pan American Airways counter. Mr. Milo March …”

I walked across the terminal to where I could see the Pan American sign. There were three men beside the counter. One of them was leaning on it. He looked about forty-five. He had all the earmarks of a cop, except that his suit had cost more than the average cop could afford. Anywhere I would have guessed he was a cop who had resigned to take a better job. His past was written in the way he stood, the way his gaze swept over the terminal.

I walked over to him. “You’re John Franklin,” I said before he could know I wasn’t just walking by.

He looked at me and knew I was showing off. But he liked it.

“Milo March,” he said and we shook hands. He glanced at the counter and the other two men. “I thought it would be easier to have you paged since we’d never met. How’d you make me?”

“Easy,” I said. “Those two are citizens. You’ve got ex-cop written all over you. And I know the Great Northern Insurance Company. They like to get their money’s worth. They’d buy an ex-cop to head their investigation department.”

“I was on the New York force for twenty years,” he said, “so I guess it might show. But how’d you figure the ex?”

“The suit. It’s too expensive even for a cop with his hand out. He’d be investigated ten minutes after he showed in it.”

He laughed. “You’d probably like some breakfast. We’ll pick up your luggage afterward.”

We went into the restaurant. I ordered breakfast and he had coffee. He waited until I’d finished my eggs.

“You’ve got about twenty-four hours to cover the background,” he said. “You want to go around by yourself, or you want me to tag along?”

“If it won’t hurt your feelings, I’ll do it alone,” I said. I lit a cigarette and went to work on the coffee. “Why only twenty-four hours?”

“Then you’re getting on another plane. If you don’t catch the one tomorrow, you’ll have to wait until Wednesday. That would put you a week behind your man.”

I nodded. “I don’t know anything about this,” I told him. “I was just starting myself a big evening last night when the head of Trans-World Insurance called, telling me to come to New York and see John Franklin of Great Northern. He told me it was a big case, but he says that even when it’s a string of cultured pearls insured for ten bucks.”

He laughed. “This time he’s right. It’s a diamond.”

“One diamond?”

“One diamond,” he said dryly. “We insured it five years ago for seven hundred thousand dollars.”

That’s a lot of money even in a Republican administration. I tried to show my respect, but my eyebrows wouldn’t go high enough. “Why me?” I asked. “Great Northern must have offices full of investigators right here in New York. Why import one from Denver?”

He pulled some money from his pocket and paid the check. “Sure,” he said. “We’ve got investigators. Good ones, too. I hired them myself. They crack most of the cases we get. But they’re not fancy. On the other hand, we’ve had some real tough cases out around Denver that were cleaned up with the kind of flourish an old cop appreciates. This is a special case. It needs someone with more imagination than Great Northern has—including me.”

One way you looked at it, it was flattering. But another way, it only meant I was going to have to work to live up to what he thought I was. “How special?” I asked.

We left the restaurant. “Our boys,” he said, “know the habits of most of the icemen working today. They can look over a job and tell you who pulled it. And they’ll know how to go about finding him. But this one was pulled by an amateur. This was his one job. He probably doesn’t want to pull another one. There’s good reason to believe he’ll never try to sell this diamond. And there are other angles you’ll learn as you go along—including murder.”

“That ought to put it in the laps of the regular cops,” I said.

“It does,” he said. “But as I said, this one needs imagination. More than they have. I’m not selling the New York department short; it’s one of the best forces in the world. But this one is over their heads, as you’ll see.”

We stopped off and picked up my luggage. Then we went out to the parking lot and climbed into his car. He didn’t say any more until we turned in to a parkway and headed for the city.

“Here’s an outline,” he said. “I won’t fill in any of the details. I’d rather you got those from each of the sources. You ever hear of the House of Stones?”

I had. A guy named Robert Stone who was one of the biggest individual operators in valuable jewels. I said as much.

“He’s that,” John Franklin said. “He deals in everything from twenty-five-dollar engagement rings to the biggest. Has an old brownstone house in the fifties. He’s a smart dealer, but he’s also a man who loves good stones. They say he’s refused to sell one that he liked. You’ll see him first.”

“He’s the victim?” I asked.

“Depends on how you look at it,” he said with a grin. “Our stockholders will probably think we’re the victims. But he had the diamond. He doesn’t have it now. He had a regular customer. A little accountant who kept saving his money and buying diamonds. The little guy liked diamonds—especially the ones he couldn’t afford. Every week he stopped in at the House of Stones. Sometimes he bought. Sometimes he didn’t. But every week Robert Stone brought out prize jewels to show him. There was one particular diamond—Stone’ll tell you all about it—he’d looked at it every week for the past five years. Two hundred and sixty times. But yesterday, while he was looking at it, Stone was called to the phone. The little accountant walked out with the diamond.”

“The murder?” I asked.

“The detective who guarded the front door. Private detective. That one’s funny, too. The cops will tell you about it.”

“You’ve got an idea where he is?”

He shook his head. “We know where he went—although we only discovered that yesterday, and it happened Wednesday. But we don’t know where he is. I’ve got a hunch there’s a big difference between where he went and where he is. The Homicide boys think it’s going to be easy. I’ve got a different idea. That’s why you’re on it.”

“Where’d he go?” I asked.

“Lisbon. It’s a small place—but from there you can get a plane to almost anywhere. And he’d been there more than a day before we even knew where he’d gone.”

“Homicide get in touch with the Policía Internacional e de Defesa donEstado?” I asked.

“State Police?” he asked.

I nodded.

“Where’d you pick up the name?” he asked curiously.

“I was there during part of the war,” I said. “OSS. Lisbon was like a convention hall for spies. If you couldn’t find a spy anywhere else, you went to Lisbon. You’d usually find him in a café on the Rossio Square listening to a fado—one of those sad songs the Portuguese listen to when they feel gay.”

He laughed. “We’ve contacted the local police. Maybe they’ll get around to looking for him tomorrow.”

“They’re slow,” I admitted, “except when somebody’s gunning for their dictator. But don’t be fooled by the fact they don’t rush around like New York cops. They still get results.”

“Probably,” he grunted. “But I’d like to make a bet. I’ll bet that nobody finds him in Lisbon—not even you.”

“Oh well,” I said, settling down in the seat. “I’ve always wanted to go around the world on an expense account.”

He laughed without humor and turned his attention to his driving. He obviously didn’t intend to talk anymore. That suited me. I relaxed and pretended I didn’t have a care in the world.

He didn’t say any more until he brought the car to a stop in front of an old brownstone building in the east fifties. “This is it,” he said. “The House of Stones. Robert Stone is expecting you. When you’ve finished with him, go over and see Captain Jim Gregory at the Nineteenth Precinct. He’ll be expecting you, too. You can also see the Homicide captain if you like, but Jim will have all the dope and he’ll give you more time. He’ll have the list of everyone else you’ll want to see.”

“Then?” I asked.

“Come back to Great Northern before closing time. We’ll have a doctor there to give you all the shots you may need. You’ve got a passport, haven’t you?”

I nodded. “It was renewed about six months ago. But I don’t need a visa for Portugal.”

“You may need one later,” he said. “Well, it’s your ball, Milo.”

“I thought it was,” I said dryly. “I caught a glimpse of the figure eight on it.” I opened the door and got out on the sidewalk. “I’ll see you.”

He nodded and drove away. I turned and went into the building. The ground floor of the old brownstone had been remodeled so that there was an outer door, then a short corridor, and finally a big door that looked as if it was made of solid steel. There was a guy standing beside the inner door. He looked like a cop. A nervous cop.

“Yes?” he asked. He tried to make it sound polite, but it came out more like a challenge.

“I want to see Mr. Stone,” I told him. “I’m Milo March. From the insurance company.”

He looked relieved. “He’s expecting you,” he said. “Just a minute.” He turned around and used a phone on the wall. All he did was announce my name. A moment later there was a buzzing sound and he swung the door open.

I went up the stairs. A well-dressed middle-aged woman was waiting at the head of the stairs for me.

“Mr. March?” she asked.

I nodded.

“This way, please.”

I followed her. We went through what seemed to be a display room. Everything was expensive and in good taste. There was a small table in the center of the room. The top of it was covered with black velvet. A small spotlight was set in the ceiling and trained on the tabletop.

She knocked lightly on the next door and then opened it. She stood to one side for me to go in. “Mr. March, Mr. Stone,” she said.

He stood up behind his desk and we looked at each other. He was probably about fifty. Well dressed. A little gray in his hair. A little heavy, but it looked good on him. A rather handsome face, deeply tanned and unlined. He didn’t look like a man who had just lost seven hundred thousand dollars.

He held out his hand and we shook. I told him what I’d been thinking. He smiled.

“I haven’t lost seven hundred thousand dollars,” he said. “The insurance company will give me the money. What I have lost is a diamond which can’t be replaced. No amount of money can do that.”

I sat down in the chair in front of his desk. “Tell me about it.”

He smiled again. “I’ve already told it so many times, I feel I could repeat it in my sleep. You want to hear about the diamond or the man?”

“Both,” I said. “All I have are the bare outlines. I could read most of it in reports, but I’d rather hear you tell it.”

He nodded patiently. “The diamond first?”

“If that’s the way you want to tell it.”

He leaned back and got a distant look in his eyes. “Mr. March, did you ever hear of the Tavernier Blue?”

“No.”

“It was a diamond,” he said. His voice had grown soft, the way some men’s voices will when they speak of a woman. “A blue diamond. One hundred and twelve carats. A man named Jean-Baptiste Tavernier brought it from India to France in 1642. Twenty-six years later, in 1668, it was sold to Louis XIV. During the French Revolution, the diamond disappeared. There have been many theories concerning what happened to it. The most popular one—which we now know to be mostly true—is that it was cut after being stolen and the cutter blundered—so the Blue broke in two. The Hope Diamond appeared in London in 1830, when it was purchased by Henry Hope. I believe it was the smaller part of the Blue. The larger half seemed to be lost forever—until 1946.”

“Your diamond was the other half?” I asked.

“Yes. I called it by the original name. The Tavernier Blue. Sixty-seven carats of blue flame. When the war was over, it was discovered among the possessions of Adolf Hitler. With it was a complete history of the stone from the day it disappeared. This, of course, made it still more valuable.”

“How big?” I asked.

He showed me with his hands. It must have been only a little smaller than a golf ball.

“And it’s really worth seven hundred thousand?” I asked.

“The value of a stone,” he said, “is determined by what someone is willing to pay for it. This one was established because shortly after I bought it, I refused an offer of seven hundred thousand. As I mentioned, the history of the stone undoubtedly increases its value. You know, Mr. March, for a long time the Hope Diamond was considered a bad-luck stone. That could more accurately be said of the Tavernier Blue. During the past three hundred years it changed hands fifty-seven times. Only five times was it legitimately bought and sold. Thirty-eight persons were murdered in the process of changing ownership. And poor Mike was the thirty-ninth.”

“The guard?” I asked.

He nodded.

“Why hadn’t you sold the diamond?” I asked. “Holding out for a bigger price?”

“No. There was enough profit in the offer.” He hesitated. “Mr. March, have you seen many valuable stones?”

“Not recently,” I said dryly. “My income doesn’t run to such things.”

“Income has little to do with what I’m talking about,” he said. “Forty years ago a man fell in love with the statue of Nefertiti in the Egyptian Museum of Berlin. He couldn’t rest until he’d stolen her. Not to sell, remember, but only that he might have her in his room to look at every day. Some men are like that about rare stones. I am myself. I could spend hours every day looking at the Tavernier Blue. It is a diamond with a real personality—one that changes every minute even as you look at it. Sometimes I had the feeling that it was the diamond that owned me, instead of the other way around. That’s why I understand Carter so well.”

“Who’s Carter?” I asked.

He looked surprised. “The man who took the Tavernier Blue,” he said.

“Tell me about him.”

“His full name is Samson Hercules Carter. I guess that represented his father’s wishful thinking. Carter’s only about five feet six and never weighed over a hundred and thirty pounds. I had a feeling he resented the name, although he never said anything.”

“Can’t blame him for that,” I said.

He nodded. “Carter first came here fifteen or sixteen years ago. He’d been coming here for a year or more, buying small diamonds—he spent about two thousand dollars every year that I knew him—before I met him. After that I waited on him myself, for Samson Carter was a man who also loved rare gems. He’d come in every week, although he didn’t buy every time he came, and I’d show him other things I had. Diamonds, emeralds, rubies, sapphires, he loved them all. We’d sit at the table in the next room and look at the stones. Sometimes for an hour, if I wasn’t too busy. Then I got the Tavernier Blue.”

“He liked that, huh?”

“The best.” He looked at me sharply. “Don’t misunderstand, March. I felt the same way about the Blue. In a way it was a bond between Carter and me—our only bond, but the sort that can exist between two people who are attracted to the same thing. After that, when he came up, I always brought out the diamond. He didn’t have to ask. I knew how he felt. He’d fallen in love with the diamond—something a lot of other men had done in the past three hundred years.”

“What happened Wednesday?” I asked.

“He came as he always did. He bought a small diamond for a hundred dollars, and then I brought out the Tavernier Blue. He obviously didn’t feel like talking and I naturally respected his desire. He’d been here about fifteen minutes when I was called to the phone. I was out of the room about five minutes, and when I returned he was gone.”

“Wasn’t it unusual to leave someone alone with a diamond worth that much money?”

He grinned wryly. “One of the officials of your company hinted that they might contest the claim on the grounds that I contributed to the theft with my own negligence,” he said. “Still, I don’t think it was unusual. I had known Carter for fifteen years. I had left him alone with valuable stones before. There was a guard downstairs.”

I shrugged. That, after all, was the insurance company’s problem. I had asked only out of curiosity. “Can you give me a complete description of the diamond?” I asked, changing the subject.

“I can do better,” he said. He opened a drawer and removed something. “Here is a color picture of the Tavernier Blue. There’s a description on the back.”

It didn’t look quite as good as a stack of seven hundred thousand one-dollar bills, but I could see why someone might want to put it in his pocket and take a walk. It was a deep blue, shot through with streaks of light. There was something almost hypnotic about it, even in a photograph. I slipped it in my pocket.

“I guess that’s about all you can give me,” I said. I stood up. “Sorry to have taken up your time, Mr. Stone.”

“There is one more thing,” he said. He seemed to be looking for something as he stared into my eyes. “I tried to tell this to the police, but it is beyond their comprehension. You seem intelligent, and Mr. Franklin says that you have imagination. There is one thing you must understand if you are to recover my diamond for me.”

He paused and I waited. There was no point in rushing him.

“Samson Carter,” he said, “is not a jewel thief. He has stolen one jewel, which is not the same thing. He will not try to sell the Tavernier Blue, and it will be a waste of time trying to catch him from that angle. He probably has enough money—my records show that he owns small diamonds worth thirty thousand dollars—but that isn’t the reason. Even if he is starving, Carter will neither sell the diamond nor pawn it. With Carter it is a matter of love. He stole my diamond as another man might try to steal my wife. Unless you understand this, you will never find him.”

“What can a diamond do for you on a cold night?” I asked. “Never mind answering that. I wouldn’t believe it. But I’ll believe what you say about Carter. I’ll look for him under a bright moon instead of three brass balls.”

As I left, he took a couple of diamonds from a desk drawer and began playing with them absentmindedly. I guessed they weren’t very important diamonds—no bigger than a couple of hickory nuts. He was playing with them the way a boy will play with marbles when there’s something else on his mind. I shook my head and left for a less rarified atmosphere.

Two

The Nineteenth Precinct was also on the East Side, only a few blocks from the House of Stones. It was sandwiched in between two fancy districts, but it looked and smelled like every station house in the country. The desk sergeant who looked up as I entered was the bored counterpart of those in a thousand other precincts. Desk sergeants are a special breed. They’ve listened to so much that everything they hear is just another item for the squeal book.

I told him who I was and who I wanted to see. He flagged down a passing patrolman and told him to show me Captain Gregory’s office. He showed me. I knocked on the door and a gruff voice told me to come in.

One look at the Captain told you his whole history. He’d come up the hard way from pounding a beat and it was written all over him. He’d probably been sitting at a desk for ten years or more, but he still looked as if he had tired feet. Sometimes that kind makes the best police official. Usually they’re not very smart, but they make up for it by being honest.

I told him who I was and he looked me over with a pair of clear blue eyes that seemed at least fifteen years younger than his sixty years.

“Insurance detective,” he said. There was no malice in his voice, but he made it sound like the tag of a dirty joke. “A fancy kind of private dick. Playing cops.”

I grinned at him. “I feel the same way about cops,” I told him. “Only I’m broad-minded about it. Some of my best friends are cops.”

He grinned back at me. “John said you wouldn’t take any of my lip,” he said. He leaned back in his chain. “John Franklin and I used to walk a beat together. He’s done all right. Sometimes I think I ought to’ve taken a job like that.”

“You wouldn’t have liked it,” I said. “They would have shoved a padded chair under your behind and taken away your cheap cigars, and you would have died by fifty.”

“Maybe you’re right,” he grunted. You could see that he liked to talk about the things he could have done, but that he wouldn’t be any place except where he was. “What can I do for you, March?”

“The works,” I said. I took the other chair in the office and got out a cigarette. “How come you’re still in on it if it’s homicide?”

He chuckled. “You know what they call this section, boy? The Gold Coast. Covered by the Seventeenth and Nineteenth Precincts. The men who live here have bank accounts that are too big, and their women are too fancy and don’t have enough to do. So the men load their women down with jewels and the women wear them. That leads to six or seven of every ten cases that come in here. Most of my boys eat, drink, and sleep jewels. You might say they’re specialists in jewel thieves. So when there’s a killing in connection with jewels, the Homicide boys get bighearted and let us work with them.”

“You do the work and they solve the case,” I said.

“Something like that,” he said. “You been down to see Lieutenant Sanderson or Captain O’Hanlon in Homicide?”

I shook my head. “John Franklin said it would be better if I came to you.”

He chuckled again. “The Homicide boys don’t take kindly to insurance or private detectives messing around in their murders. Not that I exactly blame them.”

“Sure,” I said. “But I walk real delicate. I never step on toes unless they’re shoved right in under me.”

“You look like the delicate type,” he said dryly. “Maybe I don’t like it so much when someone messes around in a case here in my own precinct, but it looks like this one got away. Somebody’s got to get him and it might as well be you.”

I nodded and waited. It was time to get started on the case; if I stopped feeding him lines, maybe he’d get around to it. He squirmed on his chair, got out a battered cigar, and lit it. He blew a cloud of acrid smoke in my face.

“See this guy Stone?” he asked.

“Yes.”

“Guess he told you how it was pulled, then,” he said. “The rest ain’t too much. Samson Hercules Carter—hell of a name for a little shrimp. Forty-two years old. Five feet six inches tall, weight one hundred and thirty. Dark hair, dark eyes. No identifying marks. Hair parted on the left side. Wears dark gray or dark blue suits, black shoes, white shirts, and dark ties. Unmarried. As near as we can learn, he never even had a girl. No known relatives.”

“Photograph?” I asked.

He snorted. “Passport picture in the files of the State Department. Could be any one of a couple thousand guys walking around. Only picture of him we can find. State Department let us make copies of it.”

He passed over a small picture. He was right. It wasn’t much to go on for identification. Flat lighting had washed out most of his features.

“Carter was an accountant,” the Captain went on. “Worked for the same firm for the last twenty-one years. Made a good salary. He was considered a good, reliable man. Never missed a day of work in all that time.”