4,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Steeger Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

In this action-packed Cold War spy adventure, Milo March—private detective and former OSS officer during World War II—is recruited by Army intelligence to carry out a dangerous mission behind the Iron Curtain. An important British diplomat has defected to East Germany, carrying with him secrets about British and American codes. He can also help the Communists gain access to a physicist working in the British Sector on a top-secret project that involves tampering with energy fields affecting the human brain―a bizarre process that could disastrously alter the nature of warfare. “Operation Berlin” demands that Milo kidnap the diplomat before the Russians make him talk.

Disguised as an American Communist delegate to an international Peace Festival in Berlin, Milo dashes into the Soviet Zone just as the news leaks that an American agent is coming to the event. Surrounded by suspicious comrades, he is congratulated on his mastery of Lenin quotes one moment, while the next he is subjected to arrest and a torturous interrogation. Even when he scores a point, he never knows whether he is fooling them or they are fooling him.

While treading this unbearable tightrope of tension, he is distracted by two beautiful women: the sexually aggressive blonde Frieda and the soft-eyed, black-haired Greta, who has some secrets of her own. Either or both of these feminine comrades could be on the verge of betraying him. Although the efficient and fearless Milo always insists on working alone, help comes from an unexpected quarter in the nick of time.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

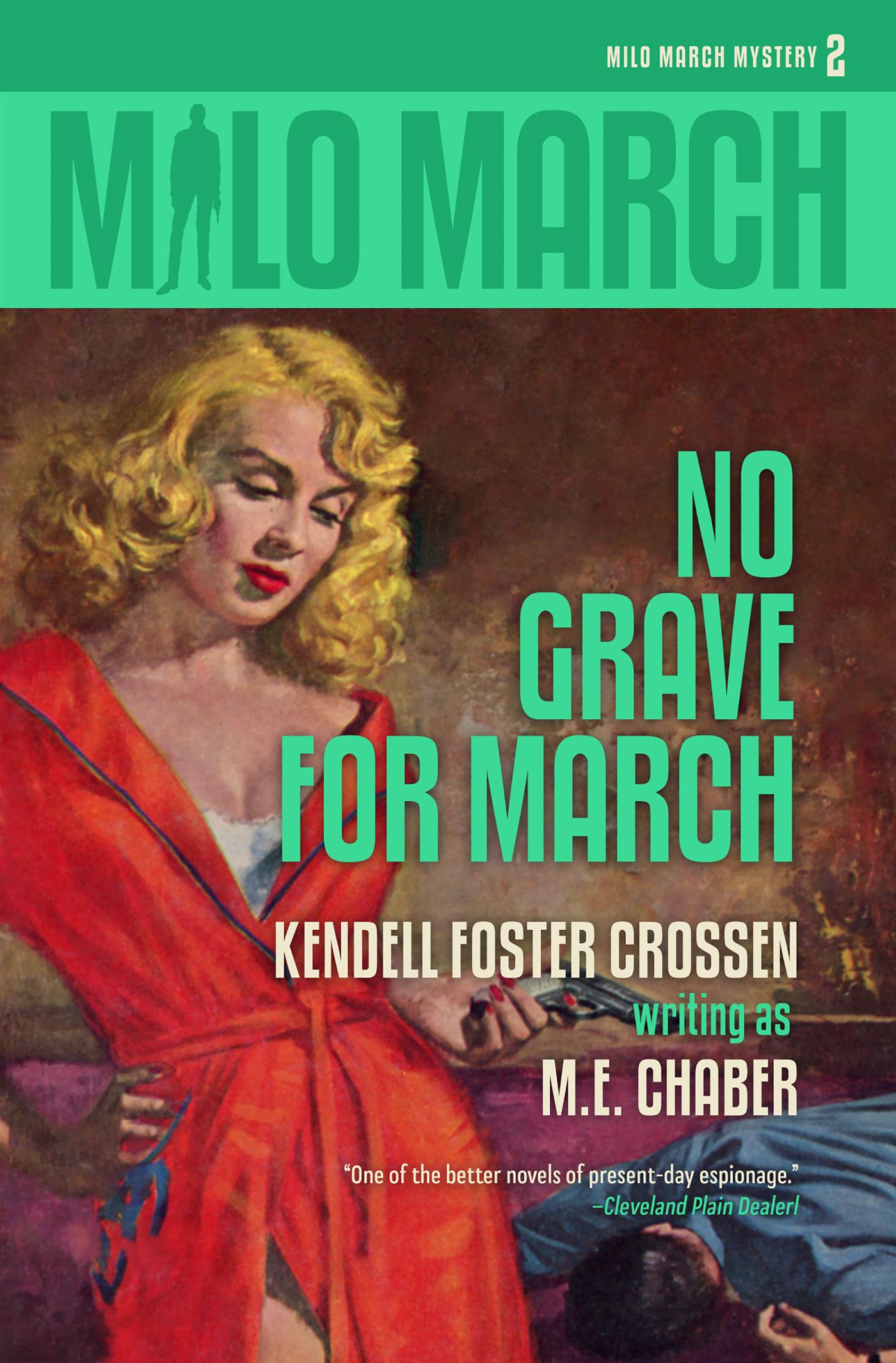

No Grave for March

by

Kendell Foster Crossen

Writing as M.E. Chaber

Steeger Books / 2020

Copyright Information

Published by Steeger Books

Visit steegerbooks.com for more books like this.

©2020 by Kendra Crossen Burroughs

The unabridged novel has been lightly edited by Kendra Crossen Burroughs.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without permission in writing from the publisher. The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law.

Publishing History

Magazine

As “Assignment: Red Berlin,” Bluebook, vol. 96, no. 2 (December 1952). Illustrated by Bill Fleming. A condensed version.

Hardcover

New York: Henry Holt & Co. (A Novel of Suspense), January 1953.

Toronto: Clarke, Irwin & Co., 1953.

London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1954.

Paperback

New York: Popular Library #530, as All the Way Down, 1953.

London: Corgi Books, T160, 1956. Cover by John Richards.

New York: Paperback Library (63-440), A Milo March Mystery, #13, October 1970. Cover by Robert McGinnis.

Dedication

For Martha

Genesis 2

Author’s Note

No Grave for March is entirely a work of fiction, but a number of persons are mentioned throughout who could not have possibly been imagined by the author. The following, therefore, are, or were, actual persons: Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Grigory Zinoviev, Jules Martov, Madame Alexandra Kollontai, Angelica Balabanoff, Jacques Duclos, William Z. Foster, Earl Browder, Wilhelm Zaisser (alias General Gomez), Erich Honnecker, Rosa Luxemburg, Wilhelm Pieck, Otto Grotewohl, Max Fechner, Walter Ulbricht, Leon Trotsky, Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, and Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin. The words attributed to Lenin were all spoken or written by him.

The two underground organizations, the Fighters Against Inhumanity and the Untersuchungsausschuss Freiheitlicher Juristen der Sowjetzone, are in existence. Rainer Hildebrandt is an actual person. Dieter Friede, Alfred Weiland, William Borm, Dietrich-Wolfgang Henckels, Horst Vollrath, Waltraud Eckholdt, Heinz Tochtermann, Siegfried Rogge, Wolfgang Hansske, Wilhelm Steneberg, Hans Saenger, and Gerda Kleinert were all underground workers who were killed or have disappeared into Soviet prisons.

Das Kapital by Karl Marx, Selected Writings of Lenin edited by J. Stalin, Lenin by David Shub, and The Rise of Modern Communism by Massimo Salvadori are all real books, available in most bookstores.

Similarly, the following persons mentioned in the novel are, or were, actual persons: Groucho Marx, Adam Smith, Senator Joseph McCarthy, Caesar’s wife, Adolf Hitler, Demosthenes, J. Edgar Hoover, Foreign Minister Anthony Eden, and Secretary of State Dean Acheson.

What is called the Warner Process is an imaginary process, but is based upon reports of experiments carried out by a French physicist.

The remaining characters in the novel are as real as the author could make them, but they are not intended to represent any actual persons, living or dead. Any resemblance to real persons is accidental and wholly unintentional.

M.E.C.

One

The corner was far enough between streetlights that I couldn’t see the face of my watch clearly. It must have been a few minutes past nine. Whoever he was, he was late. There were a few cars on the street, most of them taxis. They all kept on going. Between the sounds of cars, I could hear the wind through the trees in the park behind me. Occasionally I could hear casual feet on the walk through the park. Once I heard a girl giggle. Her voice was young and you could tell it was pointed at a man.

The sidewalk was deserted. I’d been there fifteen minutes and only one person had gone by. A girl. Maybe in her middle twenties. Neat and well dressed—the sort of clothes a careful shopper can buy on a Civil Service paycheck. A pretty face. Not on the make, but not running away either. She went slowly past me, her eyes doing a quick inventory. I counted her blessings too, but my heart wasn’t in it. She went on down the street. I thought there was an angry note to the tap of her heels as she drew farther away.

I lit a third cigarette off my second, ground the old stub beneath my foot. I glanced up at the sky and the reflected glow from the lights of the city. The nation’s capital and this was about all I’d seen of it. I’d arrived an hour before. I’d had a cup of coffee in the station after checking my luggage. Then a taxi ride to this corner. I’d been waiting fifteen minutes. I grinned to myself. Maybe, I thought, I ought to see my congressman.

Another car came drifting along the street. When it was two blocks away, its lights blinked off and then the tiny parking lights came on. It was moving slowly, close to the curb. When it was a block away, I flicked my cigarette. It made a tiny red arc, then scattered sparks over the street.

The car stopped when it reached me. The front window on my side was rolled down, but I couldn’t see the driver.

“Do you know the hour?” he asked. There was nothing to go with the voice but the shadowy figure behind the steering wheel.

“Zero for Able Fox,” I answered. It was seven years since I’d said anything like that, and I felt silly.

The back door of the car swung open. I climbed in and pulled the door shut. The car was moving again before I could get settled in the seat.

I watched the play of light and shadows across the shoulders of the man in the front seat. He was wearing an ordinary suit coat, but there was something about the set of his shoulders that told me he was more at home in a tailored uniform. By the time I’d arrived at that conclusion, I realized that none of the light from the street was flickering over me. The back windows of the car were all curtained.

“A nice night,” I said. It wasn’t exactly a brilliant opening, but I was determined to ad-lib at least one line if it killed me.

He didn’t even grunt.

To hell with it, I thought. If he wanted to be a conversation killer, I’d let him. I leaned back against the seat and relaxed. I couldn’t recognize any of the streets, so I didn’t bother watching. I didn’t know where I was going and I had an idea there was no point in asking.

After a thirty-minute ride the car pulled into a drive. It was one of those half circles, arcing in front of a large private house. There was a porch light on, but it flicked off as we stopped in front of the house. The driver reached back and unlatched the door.

“Just walk in,” he said.

“What’s the door prize?” I asked. But I knew there wouldn’t be any answer, so I climbed out of the car. It left before I could even reach the house.

It was pretty mysterious, but there was no reason to suspect anything wrong with the setup. On the other hand, I’ve already lived a few extra years by going on the assumption that there’s never reason not to suspect any situation. I had a gun in my hand when I stepped through the door.

The hallway was dark, too. At the rear of the house there was an open door with light spilling out of it. But that was all. I stood there for a minute, looking everywhere except at the light. There was another open door on my right. I waited; then I caught something that might have been a glimmer of light reflecting from polished metal. I took a quick step forward, shoving the gun ahead of me. It came up against something soft.

“Okay,” I said gently. “I don’t even have to be alive to pull the trigger. It’s your move, soldier.”

There was a chuckle from the darkness. Not with any humor in it, but a lot of satisfaction. It sounded familiar.

“All right, March,” a clipped voice said. “I just wanted to see if you’d gotten soft in the last seven years. You haven’t.” He stepped out of the doorway and walked down the hall. I followed him, still holding the gun.

His walk looked familiar too. But there were two stars on each shoulder.

He stepped inside the lighted room and turned around. I was surprised then, but not too much. The last time I’d seen him had been seven years before, just after the war was over in Europe. He’d been a colonel then.

“If you’re planning on jumping out of dark doorways,” I said, putting my gun away, “you ought to learn to strip off the polished brass. That could have been a mistake. I might have shot first and looked at your identification later.”

“I never make mistakes,” he said coldly. “I knew exactly what you would do when you stepped through the door—if you hadn’t grown soft. There was no risk on my part.”

I looked him over. Once I’d known him as well as you can know any man. We’d gone through OSS training together. We’d spent eighteen months together behind the Nazi lines in Europe, sleeping in the same ditches, gnawing on the same slice of bread.

“You’ve been a busy little bee,” I said, nodding toward his shoulders. “Two ranks in peacetime. That takes a lot of bucking.”

He didn’t like the way I said it. I remembered that he had never liked the way I said anything. He hadn’t liked me. It cut both ways. He had been an efficient little machine assembled at West Point. I couldn’t have liked him any more than I could have fallen in love with a lathe.

The room was furnished as an office. He walked around and sat down behind the desk. He still looked as if he were leading a cavalry charge.

“Major General Sam Roberts,” I said, giving it a little touch of the old parade ground. Without being invited, I dropped into the chair beside his desk and lit a cigarette. “This has been a very touching reunion. But since when has the State Department taken to talking through two-star generals?”

Now I was getting curious. All of this had started the day before when I’d gone to work as usual in Denver, Colorado. “Work” was insurance investigations for a man named Niels Bancroft. A nice guy. But he was always dropping everything to gallop off to Washington to be a dollar-a-year man. He had the idea that everyone else ought to do the same thing. So he was always telling various government officials that they ought to steal his chief investigator—me—away from him. That was the way I’d landed in OSS during the last war. This time he’d arranged to loan me to the State Department. Or so he said. I’d taken off for Washington with a hastily packed suitcase and a set of Junior G-Man instructions to meet some mysterious guy on a street corner. I’d followed the instructions and wound up practically in the lap of the Army.

“The State Department is giving us some minor assistance,” the General said. His tone implied the State Department was no more than a branch of the Boy Scouts. “I’ll brief you on that angle in a minute. Now—”

“Just a minute,” I said. “What are you major general of?”

“G-2.”

“Intelligence, huh,” I said. “I don’t like this, Sam.” He didn’t like the “Sam” either. “I’m a big boy now. I don’t like being pushed around. I want to know what this is all about. And quick. Niels Bancroft shoved me into this with some double talk about the State Department. Now I find you mumbling about Intelligence. Just drop that West Point maidenly simper and tell me what it’s all about.”

“Bancroft is a very able man—for a civilian,” he said grimly. “And patriotic. I understood that you were willing to volunteer to serve your country, March. If this is untrue, we’d better know it right now. I’m afraid, however, that in such an event we’ll have to detain you.”

“That’s what I like about the Army—it’s so democratic,” I said. “I’m willing to serve my country, but I don’t like to do it blind. I might find myself wearing a mink coat and then where would I be?”

His face was red with anger. “Your willingness to serve has to be offered blindly,” he snapped. “There is no alternative.”

“Okay,” I said wearily. “But I reserve the right to volunteer for Leavenworth if I think you’re selling me down the river.”

There was a long silence while he pulled himself together. He was obviously reminding himself that I was now a civilian. He finally unbent as much as he was capable. It was still Army, but nearer to the level of a captain than a general.

“To be truthful,” he said, “we’d be in a bit of a spot if you backed out now. On the basis of your war record and my own personal evaluation of you, I’ve already made certain arrangements. It would be difficult to make changes at this late date.”

I snubbed out my cigarette and waited.

“March,” he said briskly, “what do you know about Communism?”

“It’s unpopular in Washington,” I said promptly. “Beyond that, I’m just a native-type boy. I’ve sworn not to laugh at Groucho Marx unless he changes his name to Adam Smith.”

He wasn’t amused. I should have known he wouldn’t be. As I remembered, the only jokes he ever laughed at were those aimed at civilians, the Navy, and enlisted men, in that order.

“Never mind,” he said. “You can familiarize yourself with it tonight.” He wasn’t kidding. That’s the Army. They’ll pick some guy who couldn’t add two and two if you tied his hands, and order him to familiarize himself with calculus between reveille and lights out. “What do you think of this, March?”

He tossed something on the desk in front of me. I picked up a small green card. According to it, Milo March was a member of the Denver branch of the American Communist Party. At the bottom was the signature of somebody who was the secretary of the Denver branch. Below that was the member’s signature. It was my signature. I hadn’t put it there. I turned the card over and looked at the back. It was filled with stamps. Apparently I was in good standing.

“Very pretty,” I said, tossing it back to him. “I don’t go for that shade of green myself, but I suppose I shouldn’t be finicky. But there is a law against forgery. Or are we ignoring civilian laws these days?”

He grinned at me. It was the kind of grin a drill sergeant gives a raw recruit. “That’s not a forgery,” he said. “Your actual signature was transferred to this card by a new method. I’m told that there is no way to detect what was done.” He was enjoying himself.

“Go ahead, Comrade General,” I said.

“At twenty hours tomorrow,” General Roberts said, “the Federal Bureau of Investigations will raid the headquarters of the Denver Communist Party. When they’ve finished, the records will show that you’ve been a member of the Party since 1937. You may be interested in knowing that every single member of the Denver branch will be arrested under the Smith Act.”

“Every one?”

“Yes. Of course, if a member should happen to escape before the raid, we may have trouble getting him back.”

“So now I’m supposed to escape,” I muttered. “You know, Sam, this bit of inside information you’re feeding me sounds double-edged. Is this a polite way of telling me that if I don’t do as you want me to, I’ll be charged with the Smith Act on a frame-up? Are you trying to blackmail me into being a volunteer?”

“Oh, no,” he protested.

“Because if you are,” I continued in the same tone of voice, “you can take this little green card and shove it down your throat. And if you make any objections, I’ll shove those four tin stars down after it. No chicken colonel who’s gold-bricked his way into stars is going to blackmail me.”

He glared at me for a minute, then chuckled. “It’s just as well you didn’t stay in the Army, March. The least that could have happened is that you’d have been shot. How many times did I threaten to court-martial you?”

“I lost track after fifty,” I said. “Once I wished you had. That was the time the French general pinned some tin on us and kissed both of us.”

He got a dreamy look in his eyes and fingered the spot on his tunic where medals went. “It was a great war,” he said. Trust a general to remember it that way.

“Speak for yourself,” I said. “All this auld lang syne is fine in its place, but don’t let it get in the way of explaining your blackmail scheme.”

That put the Articles of War back in his voice. “I want to tell you a story,” he said.

“About time,” I agreed.

He ignored it. “Do you keep up with the news, March?”

“Pogo every day,” I said. “And the headlines when I feel I’m getting too cheerful for my own good.”

“Know the name of Rand Carmill?”

“Pogo’s campaign manager?” I guessed. I knew he’d go about it in his own way and all I had to do was make noises so he’d know I was still awake. He wouldn’t hear what I said until he was ready.

“Rand Carmill was a British diplomat,” he said. “He was the liaison man between the British Foreign Office and our State Department—until about two months ago. I understand that they intended to give him a better assignment, but were slow putting it through. Being unattached apparently worried him. Three weeks ago he went for a walking holiday in the British Zone of Germany and walked right behind the Iron Curtain.”

I remembered it then. For two days it had been a big sensation; then it had been tossed off the front page in favor of a bank robber.

“I read about it,” I said. “What did he do—take some secrets along with him?”

“A few,” he admitted, “but none of them very important. The problem is somewhat different. Rand Carmill is so familiar with British and American methods and codes that he will be able to interpret our every action for months ahead.”

“Can’t the codes be changed?”

“Oh, yes, but even that takes time. Because of Carmill’s years of service it may prove difficult to devise a code he can’t break. Aside from codes, he can interpret our moves for the Soviets. We have held two top-level meetings with the British. The only decision we can reach is that Carmill must return.”

“Have you discussed this with Carmill?” I asked. “Or are you just going to send him an engraved invitation from the Queen on the basis that no English gentleman can refuse?”

“You,” the General said briskly, “are going to kidnap him.”

That time he caught me with my face open. “Me?” I said, sounding like a straight man in a burlesque show.

He nodded. “We have good reason to believe that Carmill is in the Russian Zone of Germany. There are three or four rather active underground groups in East Germany, and they believe Carmill is still there, although they haven’t been able to find where he’s being kept. I suppose you still speak German?”

“Yes, but—”

“Entschuldigen Sie, wann gehen Sie?”

“So bald wie mögli—” I started to answer automatically. Then I caught myself and switched back to English. “I haven’t said I am going. Why pick on me?”

He grinned at me. “Your German is excellent, March. Your reflexes are perhaps a bit slow, but they’ll speed up once you’re on the assignment.”

“But why me?” I insisted. “The world is crawling with spies and counterspies—you can’t lift up an old pumpkin without finding one. Besides, it sounds to me like Churchill’s problem. I haven’t lost any diplomats.”

“It is equally our problem with the British,” he said. “At our joint meeting it was decided that we’d handle the recovery, since they’ll be expecting the British to make a try. As head of Intelligence, I then took over the problem.”

“Granting that Army Intelligence isn’t very high, you must have some agents,” I said. “I still want to know how I got in this mess. Just because I was in the Army with you once? You ought to give a man a chance to live down his past.”

He frowned but let it pass. “There’s too much chance any of ours might be spotted as Army men. If this is to succeed, it has to be a one-man job. I checked through all my men, and all those I worked with during the war, and I think you’ve got the best chance of pulling it off. You’re not good Army material, March, but you were one of the best men we had working behind the lines. You can do it, my boy.”

“You’re pretty, too,” I said. “How do you know I’m not a fellow traveler?”

“When you went into OSS you were pretty thoroughly investigated. I’ve just had you checked again. Hoover’s boys don’t miss much when they’re looking. I’ll admit there’re a number of things about you that wouldn’t get you by if this job had to be passed on by Congress, but I’ll stake my life on it that you’re no Red.”

“Greater love hath no man,” I murmured. I meant it. Sam Roberts didn’t value his life any more than he did the entire United States Army. “Let’s hear the rest of your story. How am I supposed to kidnap this guy out from under Uncle Joe’s wing?”

“In about a week the East German Communists are having what they call an International Peace Festival in East Berlin. Communist parties in every country have been asked to send delegates. You’re going as an American delegate.”

“Does William Z. Foster know?”

“He will. As you know, we’ve already put the top leadership on ice. The second-string leaders are on their way. And we’ve started putting special pressure on the comrades in general, with emphasis on those who are going to be delegates. Or think they are. We’ve already hit New York so hard that they’ve asked other branches to send in lists of people who might be suitable delegates. Denver included you on their list.”

“Nice of them. How was that managed?”

“We intercepted their letter. The lists were all sent to a Joseph Brown in New York, who is currently head of the Cultural Section of the Party. He’s due to go to the Festival too. We’re going to let him go. But that’s it.”

“What do you mean?”

“America is going to have only two delegates. Joseph Brown and Milo March. Nobody else is going to be able to make it.”

“That’s a big order,” I said. “How you going to swing it?”

“The Treasury men, the FBI, the Army, the Navy. We’ve got a list of all the delegates and alternates. Tomorrow there will be a lot of branches raided. There will be a small leak, and Joseph Brown and Milo March will both be tipped off, but everyone else will be netted. By the time they can manage to get bail, the Festival will be under way. I doubt if they could sneak out anyway. We’re going to let Brown go because it might look suspicious if only one man makes it. If the Party decides to send someone who isn’t picked up tomorrow, he’ll be stopped at the point of departure. For the next week it’s going to be tough for even a flea to get out of the United States.”

“How do the two delegates get out without its looking like a put-up job?”

“Brown has had passage booked for France for a month. I don’t know how he’s going from there and don’t care. His ship sails about an hour after the New York raid tomorrow. By the time we discover he’s missing, he’ll be gone. He’s scheduled to be at a meeting we’re raiding. He’ll be tipped off, but he won’t get a chance to tip anyone else.”

“And Milo March?” I asked. I was sounding just like Senator McCarthy.

“Milo March is working for the State Department. You’re taking a plane out of New York tomorrow afternoon. You’re going to Hof in the American Zone to deliver some papers to a Colonel Anderson. After you’ve given him the papers, you’ll have just about ten minutes to get across the border into East Germany.”

“Why only ten minutes?”

“Because all hell is going to break loose,” he said with a grin. “The State Department, Congress, everyone is going to discover that an American Communist, a delegate to a Soviet-sponsored meeting in East Berlin, has gone to Europe on a State Department passport. About ten minutes after you’ve seen Colonel Anderson, he will get a phone call from the Pentagon ordering him to put you under arrest. So you’d better be across the border.”

“That’s cutting it pretty thin.”

“It is,” he admitted, “but it’ll make a good impression in the right quarters. There’ll be plenty of noise about it, you can bet. You know how some of the men in Congress feel about the State Department. They’re really going to raise hell, boy, when they hear about you. And it will all be on the level.”

I looked my question.

“Nobody’s in on this,” he explained. “We’re taking no chances. There are only two people who will know that you’re the agent on this. Morton James at the State Department and myself. There are others who know we’re sending an agent, but know nothing more. So all the screaming about that dirty Communist March will be on the level.”

“Great,” I said. “Supposing I agree to go, you’ve got me into East Germany, all right. But how do I find Carmill and then get out?”

“Once you’re in East Germany you’ll be on your own,” he said pompously.

“That’s what I like about the Army. They point a gun at you and then just before they pull the trigger they tell you to figure out some way to dodge the bullet.”

“We’ll give you all the help we can,” he said. “Unless you make a mistake, you should be safe enough. There’ll be nobody coming out of America to reveal you. If anything should happen to threaten you from this end, we’ll get word to you.”

“How?”

“There’s an American radio station in West Berlin. RIAS. There’s a daily show at eight every night, giving advice to women and running matrimonial ads. Since that’s the station used by the underground, even the Soviets listen to it. You should be able to hear it anywhere in the East. If we have to get in touch with you, we’ll run a matrimonial ad on the show, using your name and mine. You’ll get the details in the orders which you’ll have to memorize and destroy before leaving Washington.”

I lit a cigarette and looked at him. “Including,” I said, “orders on how to get Carmill out of Germany, or Russia, or wherever he is?”

West Point would have been proud of him. Irony never even dented him. “We believe,” he said, “that Carmill is somewhere in East Berlin, although they may take him to Russia later. I doubt if it is feasible to expect you to march Carmill out of Berlin at the point of a gun. It will undoubtedly take guile to get him back to the Western zones.”

“The task force,” I said, “is hereby ordered to advance and display guile.”

He ignored me. “We are furnishing you with bait which may help to get Carmill voluntarily into Western Germany. Carmill was a very close friend of David Warner, a British scientist who is above reproach.”

“Caesar’s wife,” I murmured. But it was over his head.

“David Warner,” he said, “is a physicist who has been working on a special project for some time. There has been some information released on it, but very little. Warner has discovered that a tadpole is surrounded by five electrical fields. These correspond to the brain of the tadpole and the four legs which it will develop in becoming a frog. Warner has found a way to influence the fields, individually or all together. He has, for example, been able to cancel out one field and so produce a frog with only three legs. By changing the charge in the field which corresponds to the brain, he has produced frogs with a super brain capacity and others that were feeble-minded. He believes that this technique can be applied to any animal, or to man. It is believed that it may be possible to influence the electrical field of an unborn child so that he will grow up with such a strong moral sense that it will be impossible for him to follow a dictator like Stalin. This is, of course, only one of a number of similar possibilities.”

“I can see that,” I said slowly. “I’m a bright boy. I can even see the biggest possibility of all. If Warner succeeds, you’ll be able to declare war on the next generation as well as the contemporary one. Let somebody get out of line and you’ll point the Warner Equalizer, or whatever you call it, at them and they’ll give birth to a whole generation of drooling idiots who won’t give you any argument. Very pretty, my general.”

That one reached beneath even his skin. His face reddened. “Naturally,” he said, “we will only use it for defense. Or to make defense unnecessary.”

“Oh, sure,” I said. “Like Hiroshima. … Never mind. Go on with your fairy tale.”

“Warner reports that he is very near success. He recalls that Carmill used to try to talk to him about his experiments. He never revealed anything, but believes he did hint that he was getting close to the solution. Naturally, the Russians would like to have it.”

“Naturally,” I said again. “Everyone would like to turn everyone else into a drooling idiot. Pour le sport.”

His mind was wearing its girdle again. “We are providing you,” he continued, “with what purports to be a copy of a high-priority message from Eden to Acheson. The gist of it is that Warner has succeeded and is being moved to Celle in the British Zone of Germany. There will be a strong implication that the British intend to build the first Warner machine there, possibly for use against East Germany. Celle is about seventy miles due west of Berlin. Incidentally, Warner will actually be moved to Celle in the event they check in any way.”

“You think that’ll draw Carmill out?”

“I think that will make the Russians order him out. They won’t like the idea of such a machine being so close, and they will like the idea of the chance of kidnapping the man who’s going to build it. Carmill will be the only man they have who knows Warner. If they don’t get the connection, you can point it out to them. I’ll bet it will work. They’ve been specializing in kidnapping people out of West Berlin. The idea ought to appeal to them. The rest will be up to you.”

“You said that before,” I said. “And every time you repeat it, I feel a cold breeze on the back of my neck.”

“It’s a dangerous assignment,” he admitted. “I won’t try to fool you. You’ll be going there with no status other than that of an unimportant State Department man who has already been labeled a Communist here. If anything happens, every American department will deny ever having heard of you. We’ll have to. You’ll be highly expendable. But that’s not anything new to you.”

“You’re sure there’s no chance of a leak on this?”

“Positive,” he said. “James in the State Department is a completely reliable man. He and I are the only ones who know about you. Your name doesn’t even appear in any of the coded papers on this.”

“If I go, and if I get back, what’s to keep me from being shot when I land in Western Germany?”

“All American and British military personnel will be alerted for the man with the proper password. You’ll be the only man who can give it.”

“What is it?”

“Operation Berlin.”

I thought about it. I had to admit that the setup was good as far as it went. While I didn’t like Roberts, I knew from experience that he was a good man when it came to laying out any sort of maneuvers behind the lines. And I had to admit to myself that I was interested.

“What if I say I won’t go?” I asked.

“We have three other men planted for the job,” he said. “They’re not as good as you, but if necessary we can fall back on them. And you’ll be under arrest the minute you say no. No one will even know you’re under arrest until this is over. I’ve already told you too much to let you talk to anyone until Operation Berlin is finished.”

I nodded. “What about this Communist in New York?”

“He has already heard about you from Denver. Tomorrow he’ll get a telegram notifying him that you’re arriving. You’ll see him about an hour before your plane leaves. There’s a password for you to identify yourself to him.”

“Okay,” I said. “I’ll go—on one condition.”