4,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Steeger Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

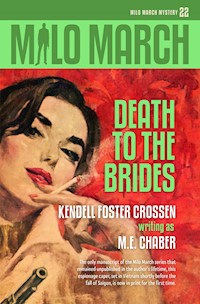

Death to the Brideswas completed in 1975 but never released during the author’s lifetime, owing to the publisher’s objection to its politically charged content. So this is the only unpublished Milo March manuscript left by Ken Crossen—now in print for the first time.

The book is distinctive in another way. It is the only Crossen book in which characters from two different series interact. Colonel Kim Locke, featured in three other spy novels by Crossen, lends Milo a miniature-breed military dog for an Intelligence mission. Milo has never worked with a canine before, but man and dog quickly take to each other, and the dog will soon prove himself a valuable friend in a world gone mad.

The American war against the Viet Cong is supposedly over now, and the only U.S. personnel in the South are advisors and attachés. Milo arrives under cover as the new military attaché, assigned to rescue an Intelligence man held captive in the highlands of the North. He decides to present himself to the Communists as an American officer who has come to plead for the release of the prisoner on the humanitarian grounds that he is a civilian and a personal friend who was captured while on an errand of peace. But how to reach Hanoi safely?

An informant sends him to Madame Lê, a beautiful young Chinese Vietnamese woman who is a restaurateur and an officer of the Viet Cong. She is willing to guide Milo on an arduous walk through the jungle. Mindful of the possibility that Madame Lê or her comrades may lure him into the hands of the Viet Cong, to be thrown into the same cell with the American he came to rescue, Milo is taken by surprise when the real danger comes from a completely unexpected quarter.

Milo, who never make plans in advance—except the plan to stay alive one more day—embarks on one of the craziest stunts of his espionage career. And the little dog holds the key.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Death to the Brides

by

Kendell Foster Crossen

Writing as M.E. Chaber

With a Foreword by Richard A. Lupoff

With an Afterword by Kendra Crossen Burroughs

Steeger Books / 2021

Copyright Information

Published by Steeger Books

Visit steegerbooks.com for more books like this.

©2021 by Kendra Crossen Burroughs

First Edition

The unabridged manuscript (1975), has been edited by Kendra Crossen Burroughs and Richard A. Lupoff.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without permission in writing from the publisher. The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law.

Americans see history as a straight line and themselves standing at the cutting edge of it as representatives for all mankind. They believe … that there is nothing they cannot accomplish, that solutions wait somewhere for all problems, like brides.

—from Fire in the Lake: The Vietnamese and the Americans in Vietnam, by Frances FitzGerald

Foreword

1974 and All That

Kendell Foster Crossen was as versatile an author as he was prolific. In addition to hundreds of short stories, he penned some forty-five novels, several comic book series, and many radio and television scripts. He was the author of two series of novels. In the first, the Green Lama, a vigilante crime-fighter based very loosely on the popular Shadow, was featured in fourteen short novels, and would probably have continued for many more had the magazine in which his exploits appeared, Double Detective, not been sold to another publisher who changed its orientation from crime and mystery stories to the sex-and-sadism themes of the so-called “weird mystery” genre.

Crossen’s second major series featured Milo March, a World War II veteran turned insurance investigator and de facto private eye. Milo had served in the OSS (Office of Strategic Services), forerunner of the CIA. After the war he retained his commission as a reserve officer and from time to time was recalled to duty, thereby providing Crossen with reason to insert a spy thriller into what was otherwise a fairly straightforward private eye series.

Twenty-one Milo March novels were published during Crossen’s lifetime. Crossen wrote a twenty-second Milo March novel. In this one, Milo is recalled to the Army, summoned to the White House for a meeting with the President, and dispatched to Vietnam to rescue an important American being held prisoner in Hanoi.

The novel, titled Death to the Brides, was completed in 1975. The years 1974–1975 were tumultuous. Diplomatic teams headed by Henry Kissinger and Le Duc Tho had reached a truce agreement in Paris in 1973. It was an open secret that this was a flimsy device to save face for the Nixon Administration. After what was referred to as “a decent interval,” all concerned expected the flimsy government of South Vietnam would collapse and the country would be reunified with its capital in Hanoi.

In the meanwhile, President Nixon was besieged by critics because of the Watergate scandal. At first, Nixon dismissed the incident as “a second-rate burglary,” but his attempts to cover up the crime drew him deeper and deeper into a morass that eventually cost him the Presidency.

In the midst of this complex tangle, Milo March flies to Vietnam to begin what would be his final series of exploits. But when Crossen’s editor at Holt, Rinehart & Winston read the manuscript, he demanded changes that Crossen was unwilling to make. Chiefly, Nixon appears onstage, not named but clearly indicated. Crossen’s portrait of the President was, to say the least, not flattering. Later in the book, without overtly taking sides, Crossen implies that the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong were not so much Communist aggressors as anti-colonial nationalists.

Author and publisher at loggerheads, the manuscript was returned and never published—until now.

The author’s executor, his daughter Kendra Crossen Burroughs, asked me to apply an editorial brush to the manuscript. As ex-military, it was not difficult for me to work through the manuscript and clarify details of protocol, uniform conventions, and insignia of rank. I also interpolated a few brief lines of dialog to clarify matters in the narrative. As for the politics of the book, it would have been totally inappropriate for me to change Crossen’s expressed ideas. And in fact the passage of four decades has shown that he was far more right than wrong.

As a dedicated fan of Ken Crossen in general and Milo March in particular, I recommend Death to the Brides as a worthy grace note to the Milo March series and to Ken Crossen’s fine career.

Richard A. Lupoff

One

The name is March. Milo March. I have a small office on Madison Avenue in New York City. The upper half of the door is opaque glass. On it is printed: March’s Insurance Service Corp. Another line below it announces that I am president. I am also the corporation, the only stockholder, and the only employee. Normally, if that word can be used in connection with anything I do, I am an insurance investigator. It’s a living.

I unlocked the door and stepped inside. The mailman had been there and the mail was on the floor, where it landed when pushed through the slot in the door. I scooped it up and walked to my desk. I tossed the mail on top of it and hung up my coat. As I sat down, I noticed that one envelope was sticking out from the others. The return address was a box number in Washington, D.C. There was something familiar about it, but I couldn’t think what it was at the moment.

I opened the drawer of the desk which contained a bottle of bourbon and a glass. I put them on top of the desk. Then, feeling prepared for anything, I picked up the letter and opened it.

I was right about it. The box number was one that I remembered, and the clincher was that the envelope was addressed to Major Milo March. I opened the envelope and pulled out the letter. The first word I saw was “Greetings.” I put it down and poured myself a drink. A quick drink gave me enough false courage to read the rest of the letter.

It wasn’t exactly the sort of news that thrilled me. It merely told me that I was being recalled to active duty in the United States Army Reserves.

I must confess: I have another job, but it’s only part time. You might guess it has something to do with the Army. In fact, it has everything to do with the Army. I had spent several years assigned to Army Intelligence or to the CIA, usually in espionage.

They had taught me a number of things which just wouldn’t look right in civilian life, so when my tour of duty was over, they asked me to enlist in the Reserves. Like a damn fool, I did. This was the sixth time I’d been recalled to active duty. The letter told me that there was a reservation on a plane for Washington and ordered me to be on it in full duty uniform. It also included the information that I would be met at the airport in Washington and that I would be paged after the plane unloaded.

I picked up the phone and dialed the number of Intercontinental Insurance, my chief employer. When the girl answered, I asked for Martin Raymond, who was a big wheel at the company. The next voice I heard was that of his secretary.

“Hi, honey,” I said. “This is Milo March. Is the great man in and available?”

“He’s in, but I don’t know about the rest of it. The last I knew he was working on the crossword puzzle. You want to ask him for money?”

“Goodness, no. I may sometimes pound on the desk and demand money, but I never ask for it. It would be beneath my dignity.”

“Well, I’ve never known you to be interested in more than two things. If it’s not money, then it’s girls. But where does our Martin Raymond fit into that picture?”

“He doesn’t,” I said. “Just ring him and tell him I want to talk to him for a moment and that it’s important.”

“All right. I’ll tell him that you don’t want any money, and that will put him in a good humor for the entire day.”

I held the phone and waited. I heard the click as he picked up his phone. “Milo, my boy,” he said. “How are you?”

“Just fine. I only wanted to—”

“Glad to hear it. Tell me, what’s a four-letter word meaning a constant irritation?”

“Boss.”

There was a moment of silence, then he gave what was supposed to be a laugh. It sounded like a whinny. “That’s my boy. Always pushing the big laugh meter.”

“You laughed too soon, Martin. The next line is better. If you have a job for me within the next few weeks, don’t call me.”

“What? Why not?” He sounded as if I were picking his pocket. “You know we have you on a first-call basis. Who offered you a job?”

“It’s not a job. It’s more of a command. You remember the United States Army?”

“But that’s impossible. You’ve been in the Army. Several times. Besides, it was announced that we’ve achieved a new peace—with honor.”

“Martin,” I said gently, “they didn’t say whose honor. They merely ordered me to be there today. The only additional message was that there would be somebody meeting me at the airport.”

“That must be unconstitutional!”

“They sneaked it through one day when you were at the club,” I said wearily. “I’ll call you when I get back.”

“We’ll miss you,” he said, making it sound like a funeral speech. “And I want you to know that we at Intercontinental are proud of you. When it gets rough, you can be sure that we’re back of you all the time.”

“How far back, Martin?”

“What?” He sounded puzzled.

“Remember General Custer? He fought the Cheyenne at Big Horn. The main body of soldiers, led by General Terry, was back of Custer. They were so far back they didn’t arrive in time. You know what happened to Custer, don’t you?”

“Well … not exactly. He was—ah—”

“Killed,” I said abruptly. I hung up without waiting for an answer.

I folded the letter and envelope and put them in my pocket. Then I called my answering service and told them to take messages until they heard from me. I had a drink and then left.

I stopped at my bank and cashed a check to make sure I could hold out until I got some expense money from the Army. Then I went out and hailed a cab, giving the driver my address in the Village.

When I reached the apartment, I poured myself a fresh drink and sat down while I thought about what I needed to take with me. Fortunately I had one service uniform which hadn’t been worn since it came from the cleaners. I quickly changed into it. I put the rank insignia on my shoulder tabs, then strapped on my shoulder holster. My gun was in the drawer, and I took it out and examined it. I had cleaned it earlier that week and it looked almost new. I slipped some shells into it and put it in the holster. Next, I pinned my fruit salad on the left breast of my jacket and put it on. All that remained was the packing of a small suitcase and donning my cap. As I left, I glanced in the mirror. I would at least pass muster.

Downstairs, I flagged down a taxi and told him to take me to the airport. Then I leaned back and didn’t even think of what was ahead of me.

I was at the terminal early, which I had planned. I went into a bar and tried to look like any soldier on his way from one assignment to another. A martini in front of me helped the illusion.

I finished it and went to the desk to pick up my ticket. My flight was announced as I turned away. I carried my suitcase with me and got my pick of the first seats. I put my suitcase under the seat, leaned back, and fell asleep before we left the ground.

I awakened just as we were coming down in Washington. That gave me enough of a start to be one of the first passengers out of the plane. I went straight to the nearest bar in the terminal. I ordered a martini, lit a cigarette, and waited to hear a voice from the loudspeaker. What I heard was a small, soft voice from right behind me.

“Major March?”

I turned to look. It a very pretty young woman wearing an Army uniform with three stripes on the sleeve. She was standing very stiffly behind me.

“I’m Major March,” I admitted.

She snapped a salute and held it. “Sergeant Marya Cooper. Reporting for duty, sir.”

“Well,” I said. “I wasn’t told I was being put in command of the smallest and most attractive company I’ve ever seen. My first order is that you sit on this stool next to me and have a drink.”

“I’m sorry, sir, but I can’t drink. I’m on duty.”

“So am I. On duty and drinking. Didn’t you ever hear of women’s lib?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Do you approve of it?”

There was a slight hesitation before she answered. “Most of it, sir. The feminists have said many things which should have been said long ago.”

“It was,” I told her, “but nobody listened. The women were too busy over a hot stove and the men were too busy being served a few shots of whiskey and then popping Sen-Sen into their mouths to remove the odor before they went home.”

She smiled then. “You don’t look as if you are old enough to remember that.”

“I’m not. But when I was young, I was advanced for my age. And I never liked anyone giving me a hard sell on anything, so I did my own research and came up with the right answers before women’s lib climbed on their first platform. Are you supposed to take me somewhere?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Where?”

“To your destination, sir.”

“Now, here we have a nice progressive group. The Army. First they brainwash you, then they fill you with a lot of nonsense so you’ll talk like a second lieutenant by the time you have three stripes. When you reach that point, you’re afraid to go to the bathroom because it might damage national security. Well, let’s go, Sergeant.”

“Yes, sir.” She turned and strode away.

I followed her, and she stopped when she reached a big black Cadillac. “This is it,” she said.

“I crossed behind the car to reach the right front door. As I went, I noticed that directly above the license plate there were three silver stars. I opened the door and slid in beside her. “Do you drive for General Roberts?”

“No, sir.”

“Are the three stars meant to indicate the importance of General Roberts?”

“No, sir. This car belongs to General Baxter, who has borrowed you from General Roberts. I am General Baxter’s secretary, and I sometimes drive it to pick up someone who’s important to him.”

“Sounds like a nice fringe benefit for you. I have a car just like it, except that it doesn’t sport three stars and it is bulletproof.”

“Why?”

“It makes me more secure when there are generals standing behind my back. Who and what is your general?”

“General Baxter is in command of Army Intelligence.”

“That makes him a kissing cousin of General Roberts. They remind me of two old ladies arguing about which one gets to borrow a cup of sugar.”

She glanced at me and there was a smile on her face. “You know, I don’t think you’re so tough. I think you’re a pussycat.”

“That’s more like it. Where did you ever get the idea that I was tough?”

“From General Baxter. And I read reports on a couple of your missions.”

“General Baxter and I never met,” I said, “so how can he make such a statement about me? And the reports are pure fiction.”

“I thought that was your advantage in taking on the new assignment with such a detached manner.”

“It’s some advantage, but I have one that’s more important.”

“What?”

“He needs me. He wouldn’t be borrowing me if he didn’t. When you want something badly enough, you pay the going price. These are the rules of the game that they recognize and accept. Both sides do this.”

“Do you accept those rules?” she asked.

“Partly. No more than that.”

“What do you accept and what do you reject?”

“I accept those rules,” I said, “as guidelines for the men who plan the mission. When it comes to being assigned to the mission, the only rules I accept are my own. The same thing is true of other agents—or they don’t survive.”

“Men like you?”

“More or less. Each man assigned to a mission has a double solution to provide. First, he must accomplish what he is asked to do. Second, he must survive and not be captured. If he fails in the second, then he has wasted part of the assets of the group that sends him out. In one way, the second solution is more important. If he is killed, it is almost certain that it will be far more difficult for an agent who may be ordered to follow him on the first mission. Perhaps impossible.”

“Where do they find men like that?”

“Anywhere,” I said, “from right underfoot to a far-flung corner of the world. The world has many such men. They seemingly obey all the rules, but they invent the game as they go along. Generals like Baxter and Roberts know this and will pay the price.”

She swung the car to the side of the street and came to a stop in front of a large hotel. “We made a reservation for you in this hotel,” she said. “I’ll pick you up in the morning and take you to General Baxter. May I ask you one more question before you get out?”

“Sure.”

“You make it sound more complicated than I thought. Can you simplify it for me?”

“No, but I can explain it a little better. When someone, like General Baxter, decides to send a man into another country on an Intelligence mission, he knows that he is sending one man to connive and even fight, if necessary, against an entire country. If he wins anything, it will be a victory that will long be remembered. People in small, dark offices all over the world will laugh. Some will laugh with joy and some will laugh through tears. In other offices, there will be someone who pins up a picture of the agent—if he’s been careless. There may be a line suggesting that anyone who sees him should fire first and explain later.”

“Are you making that up?”

“No.”

“Do you know where your present assignment will take you?”

“I can guess,” I said. “I’m sure you know, but I don’t want to hear it from you. I’d rather depend on my guess.”

“Where?” she asked doggedly.

“The only place that fits everything I’ve heard from you.”

“But it’s dangerous.”

I smiled at her. “So is climbing into a tub to take a bath. Or crossing the street. Or being in the Army, for that matter.”

“Where?” she repeated, her voice sounding strained.

“Vietnam.”

“But we’re at peace with them.”

“Sure,” I said. “It’s called peace with honor, but it does overlook a few things. We still have thousands of men there. They may not be flying the American bombers that have been sent to South Vietnam, but we’re training the men who fly them. And once in a while, one of our pilots may make a flight just to help an old buddy get some sleep. We also have a lot of military and civilian advisors to answer questions. Plus military guards around to keep an eye on American civilians—and anything that interests them. You see, we are keeping the letter of the peace treaty but not the meaning of it.”

“And what part will you play in it?”

“A small part. Just a walk-on. You’re a smart girl. Figure it out when you go to bed. Now, how about having dinner with me tonight?”

She shook her head, smiling. “I don’t think General Baxter would approve.”

“How about coming in and having a drink with me?”

“Sorry, sir. I’m still on duty.”

“All right. Dinner tomorrow night or lunch tomorrow?”

She laughed softly. “We’ll talk about it tomorrow. I’ll pick you up here at eight o’clock.”

“Okay,” I said with a sigh.

I got out of the car and walked inside. I checked in at the desk and followed a bellman into the elevator and then into a room. As soon as he was gone, I looked around. My appreciation of General Baxter went up several degrees. It was a suite instead of a mere room. I decided it wouldn’t be polite to complain about it.

After hanging up my jacket and tie and putting the gun in a dresser drawer, I phoned room service. I ordered a bottle of bourbon, some ice, a glass, and a rare steak dinner. Then I left a wake-up call for the morning. I turned on the television set and waited.

When the waiter arrived, I signed the check and added a tip. As soon as he left, I took off the rest of my clothes, poured some bourbon, and was ready to tackle the steak and the bourbon at the same time. I was afraid I might not last through the food and the drink. I was right about that.

Two

The television was still on when I awakened, but that didn’t surprise me until I realized The Today Show was what I was watching. I had slept through the entire night. It wasn’t even time for my wake-up call. I looked at my watch and saw I could just make it. I went into the bathroom. I shaved and took a fast shower. The phone rang just as I returned to the other room. I had the operator switch me to room service and ordered two scrambled eggs, an English muffin, ice cubes, and coffee. I went back to put on some clothes and turn off the television.

The knock came on the door and I opened it. The waiter entered with my breakfast. I signed the check and added his tip. I was back by the small table by the time he was gone. I splashed some bourbon into a glass and sat down. The bourbon was just the thing I needed.

I finished dressing and sat down to wait. I had finished about half the bourbon when the phone rang. I picked up the receiver and answered. It was the desk clerk. Sergeant Cooper was downstairs. I finished the drink, buckled on my gun, put on my jacket and cap, and left the room.

She was waiting outside in the car. I opened the door and slid in next to her. “Good morning,” I said.

“Good morning, Major March. Did you have a good sleep?”

“Fine. I awakened about forty-five minutes ago. Just time to shave and shower and have breakfast with a drink.”

“How did you spend the evening?” she asked. “Chasing strange girls through the staid halls of the hotel?”

“Not me. I turned on the television set and ordered a steak dinner, a bottle of bourbon, and ice from room service. I enjoyed all three. That’s known as clean living. Then I went to sleep without bothering to turn off the television or the lights. I slept the sleep of an innocent.”

“That must have taken some doing. I went back to the office, read some of the reports on you, went home, turned on my record player, and went to sleep.”

“If you read some of those reports, that should have been enough to put you to sleep.”

“On the contrary, it was interesting. It made me understand a lot of things that you said last night. And what you said about men like you. I had never thought of your work as being one man at war against an entire country. The fact that you’re successful at it explains why you get away with breaking regulations and still manage to collect all of that fruit salad. And I also know you have more that can’t be given you, because the ribbons provide information that would be a security risk for you. Tell me, sir, do you also collect women the way you collect medals?”

“I do not collect women,” I said. “I like women. I enjoy talking with women. I get pleasure from looking at women. I get even more pleasure from making love with them. Does that answer your question?”

“I think so,” she said. There was something in her voice that sounded like a smile. “I imagine that both activities require a certain amount of intelligence work, but I’m afraid the Army doesn’t issue medals in the second area.”

“Please,” I said. “You’re touching on a tender spot. I have always felt I was a failure because I’ve never been given a good-conduct medal.”

“I’ll leave a note for General Baxter. In the meantime, relax. We’ll be there in five minutes. Don’t forget that he’s taking you to meet someone. You might call it a command performance. Then you may have some personal plans for the day.”

“I do. Suppose we have dinner tonight?”

“We’ll discuss that later. Anything else?”

“Since I don’t know what day I’ll be leaving Washington, I’d like to get some money and buy additional military clothes.”

“I already have a voucher for you, and I’ll drive you to the store. Is that all right, Major March?”

“If you can’t call me General, then just call me Milo. Isn’t that the Pentagon?”

“Yes. We’re driving right inside of it.” She proceeded to do just that, ending up on a huge platform. It immediately took us up several floors. She drove off and pulled into a parking space with General Baxter’s name on it.

We walked down a long corridor, went through a door, and then walked down a shorter hallway. We stopped beside a small enclosure that contained a desk, two chairs, and a large filing cabinet.

“This is my office,” she said. “I’ll tell him you’re here.” She picked up the phone and spoke softly into it, then replaced the phone and looked up at me. “Go right in. He’s waiting for you. Just be yourself. He may frown sometimes, but inside he’ll be friendly. Good luck.”

I nodded and stepped to the door, which was only a couple of feet away. I opened the door and there he was: a tall, trim man with gray hair and a curious expression on his face.

I stopped and saluted him. “Major Milo March reporting for active duty, sir,” I said.

“At ease, Major.” He motioned me toward a chair in front of his desk. I went over and sat down. “Cigarette?” he asked. I took my lighter and held it to his cigarette. Then I pulled out one of my own brand and lit it.

“I’m sorry we never met before,” he said. “Normally, we should have, but I’m afraid that General Roberts likes to keep his men under cover even at home. Actually, you were originally assigned to us, but the General borrowed you and then decided that possession was the better part of a contract.”

“That sounds like him. General Roberts and I have known each other for a long time and have had our differences of opinion since our first meeting.”

He smiled. “Having read your files, I think I can understand that. I must admit that I’m impressed by your files, but I can see that a commanding officer might take a dim view of your attitude. You have broken almost every military regulation I can think of, and many reports give the impression that you were lucky in being able to accomplish your mission and return safely. I do not accept this theory. The agent who depends on luck seldom accomplishes anything and seldom returns. I got a feeling from the reports that you went into every situation with an exact knowledge of how you would reach your destination, the best way of accomplishing your mission, and at least an idea of how you would get back.”

“Fortune favors the bold,” I said.

He was staring at me. “Is that idea of your own creation, Major?”

“I’m sorry to say it isn’t, sir. Some Roman fellow named Publius Vergilius Maro said it. Audentes Fortuna iuvat. The Goddess of Luck helps those who dare. It’s been kicking around for a long time.”

“Good grief, March, do you know everything?”

“Hardly, sir. I’m afraid I’ve got a mind like a vacuum cleaner. It picks up all sorts of things. Some of them are just dust and scraps, but others turn out to be pretty worthwhile, like the line from Virgil.”

He nodded, smiling. “You know, I’ve often thought that poets and philosophers should be required reading for intelligence agents. Has Sergeant Cooper told you where you will be going on this mission?”

“No, sir, but I’m sure I have guessed where it will be.”

“Let’s hear it.”

“Vietnam.”

“Why do you think so, Major?”

“It’s the only logical place. Vietnam.”

His eyebrows lifted quizzically. “Why there?”

“We have peace there, but it doesn’t mean a damn thing. We still have a hell of a lot of men there. Sure, I know they’re not supposed to be fighting, but I’d like to have a bundle of money for every Vietnamese, from North and South, that Americans have killed. Soldiers and civilians.”

“I think that’s true,” he said, “but where the hell do you get your information?”

“I do know something of what has happened and is happening in Vietnam. I was there five years ago and then I was there again a little more than a year ago. I also have personal friends all over that area who give me information when I want it.”

“I thought you must have been there about a year ago. One of my men got some unexpected help in Vietnam about that time. I thought it looked like your work, but I checked on the records and you were supposed to be in Cambodia. Who assigned you to Vietnam?”

“I did,” I said. “I was sent to Cambodia by the CIA, but that job was pretty much under control. A friend of mine told me that an Army Intelligence man needed some help near Saigon, so I went there.”

“Is that the only time you have made your own orders and then followed them?”

“Not exactly.”

“Has anyone briefed you on your present assignment?”

“No, sir.”

“I will do so,” he said. “Later. First I’m taking you to meet someone. I very much doubt you’ll get any information or pleasure from the meeting, but I have no alternative. You do have my permission to answer any and all questions as you see fit.”

“I’ve never met such a nice-talking general in my life. May I ask where we’re going?”

“The White House. All roads in Washington lead there. Let’s go.” He stood up and led the way out of the office. “We’re ready to go, Sergeant.”

“So am I, sir,” she said.

He nodded and led the way. Sergeant Cooper slid in under the wheel. I held the back door open for the General. I hesitated only a minute and then climbed in next to him. I would rather have sat up front with her, but that might be breaking too many records in one day. I knew I’d been right when I noticed the tug of a smile on his lips. It gave me another clue to him. He was a man who liked to make bets with himself, and he had just won the bet.

In minutes we were there and she turned into the White House grounds. After winding around a few short curves, we pulled into a parking area labeled “Army.” The General looked at his watch as we got out. “I don’t think this will take long, Sergeant,” he said. “But you can turn off the motor. We don’t want him to think we’re wasting energy. Come on, March.”

As I fell into step with him, I noticed the little smile was busy once more. Maybe he wouldn’t be so bad to work for after all. We entered what seemed to be a side door and walked down a long hallway. There was no sound except that of our feet on the floor.

“We check in here first,” he said, stopping in front of a door. “You are about to meet another general.”

“How lucky can I get? The worst that can happen is that I get blinded by the lights reflecting from stars.”

“He is Brigadier General Manchester, presently the chief aide of this part of the White House. In civilian clothes and on temporary leave from the Army. He’s our last sentry post.” He tapped on the door and a voice answered from the other side. General Baxter opened the door.

“Good morning, General Manchester,” he said. “This is Major March, temporarily working with me.”

“Good morning, Major March,” the man said. He studied me for a few seconds, then his gaze returned to Baxter’s face. “He’s expecting you. Go on in. I’ll let him know that you’re on the way.” He reached under his desk, and I suspected there was a button there.

We turned and stepped across the corridor. General Baxter looked at me with a strange smile on his face. “This is your big moment, Major.”

“I can hardly wait,” I said as he opened the door.

Although I had guessed who we were going to see, I would have recognized him the minute I saw him. His face reminded me slightly of Bob Hope’s. The big difference was that if it had been Hope, I would have probably laughed when he spoke. Nothing like that happened. He stared at me with an expression that must have been like that of a slave buyer being offered the first item on the block.

“I’m glad to see you, Major March. I’ve heard so much about you that I feel as if I’ve known you for a long time. I suppose you have your game plan ready?”

“I beg your pardon, sir?” I said.

“Your game plan,” he said impatiently. “I know you must be a team player, and I’m sure you give your players all of your instruction before you get on the field.”

I took a quick glance at General Baxter. The small grin was again tugging at the corners of his mouth. I shrugged and turned back to the man at the desk.

“I’m afraid, sir,” I said dryly, “that you are confusing my mission with this week’s football game. It’s true that I’m in charge of the action, but I’m also the only player on my team. It does, however, bear one resemblance to a football match: if anyone throws you a forward pass, you’d better make sure you catch it and get rid of it without waiting to admire it.”

His smile stiffened as he picked up something and came around the table. “I know your record, Major, and it’s one to be proud of. I have the honor of giving you one of the rewards that is due you.” He reached up and fumbled with one of my shoulders. He moved around and did the same thing with my other shoulder. He tossed something on the desk but continued to fumble. I glanced down at the desk and saw my bronze oak leaves. Then I looked at one of my shoulders and got a glimpse of a pair of silver eagles.

“Congratulations, Colonel March,” he said as he moved back in front of me. I automatically stood at attention and started to salute him. “That’s not necessary,” he added. “In this office, I’m just one of the fellows. Now we’ll do that once more for the record.”

“What record?” General Baxter asked quietly.

“It’s a regular procedure here. Whenever I give any sort of award to a man, we have it photographed and sent out to all the newspapers. The friendly ones, at least. The photographer is in the next room. I’ll get him right over here.”

“There are to be no pictures of Colonel March,” the General said. “There are at least a dozen countries looking for photographs of our men. The minute they find one of Colonel March, he’ll be a dead hero within days. This is a matter of national security, sir.”

“I agree with General Baxter,” I said. “If your photographer comes in here with a camera, he’ll leave with a broken camera. Now, if you’d like to take back these pieces of silver on my shoulders, you’re welcome to them. I’ve seen the defoliation you’ve ordered in Vietnam. I don’t care to be the victim of another such order.”

His mouth tightened with anger. “All right. I thought you were a real man.”

“You wouldn’t know one if you saw him. You’re a small man in a big job. Why don’t you go back to warming the bench for some small-town football team?”

He pushed some papers on his desk, and I noticed his hands were shaking. “Get out,” he said. “Keep your damn promotion. Maybe we’ll see if you still have it after a court-martial.”

“At your service, sir. General, let’s go out and get some fresh air.”

“A good idea, Colonel,” General Baxter said. “Let’s consider that we achieved peace with honor. Go ahead, March. I’ll cover your back.”

I opened the door and stepped outside. He joined me and we walked down the hallway and outdoors. Sergeant Cooper was out of the car and had the door opened by the time we reached it. “Straight back to the Pentagon,” Baxter told her. He glanced at me. “There should be someone there waiting to see you.”

“What is this, Show and Tell day?” I asked. “Well, it can’t be too bad if he’s coming to see me. It’s better than being dragged in and being told to perform.”

“What performance do you mean?” the Sergeant asked.

General Baxter told her about our visit. He did embellish it slightly, but she seemed to enjoy it. “You must be very brave, Colonel,” she said over her shoulder. Speaking of which, I could tell she was looking at mine.

“Pardon me, sir,” she said, “but weren’t you just a major?”

I grinned. “That’s right.”

“And now you’re a bird colonel? You didn’t get a promotion. You skipped right over lieutenant colonel to full colonel!”

“The Commander-in-Chief giveth,” I said. “And speaking of bravery, there is a Chinese proverb: ‘He who is too brave may not live long enough to prove it.’ ”

“I suppose you speak Chinese?” she asked.

“Shih. Pu ts’ui.”

“What’s that mean?”

“Yes. Of course I do.”

“And Vietnamese?”

“Mot thu tieng thi khong bao gio du.”

“He does,” General Baxter said, ending that conversation. We were already in the Pentagon and soon pulled into the General’s parking place. “Colonel Locke,” he continued, “is waiting for us in my office. Our talk with him shouldn’t take long. Sergeant Cooper has a voucher for you and she will get it cashed. She’ll wait for us to finish with Locke, then she will send you to look at a photograph of a man. I want you to memorize his features. Sergeant Cooper will take you to do your shopping.”

“Thank you, sir.”

By this time we had reached his office. There was a girl wearing the stripes of a corporal sitting at Sergeant Cooper’s desk. She looked up and seemed relieved at the sight of us.

“Sorry we’re a little late,” Sergeant Cooper said. “Did Colonel Locke arrive?”

“Yes. He’s inside waiting, but he seemed a little impatient when I told him to go in. He had a dog with him and insisted it had to go with him.”

Sergeant Cooper smiled at me. “By this time he’s probably tried to find his own files so he could read the reports. He’s the only other person whose files read like those of another colonel we know.”

“I’ve never had a dog in my life,” I declared indignantly.

“You should have asked for one at the office where you went this morning. He usually has several dogs who help to rescue him when the heat is too much.”

“I didn’t know you were talking about two-legged dogs,” I said.

The General cleared his throat. I guessed it was a signal and wheeled around to face him. “We’d better go, General, before the plantation hands get too restless.”

He smiled as he opened the door. I followed him into the offices.

There was a man sitting near the desk. He wore civilian clothes, but I recognized his face. There was a dog lying on the floor next to the man’s feet. I remembered one of them. The man was Kim Locke, but the dog was unfamiliar, and the minute he saw me he stood at attention. He was small and muscular with a black and tan coat. He could have passed for a fierce Doberman pinscher who’d been put through a mad scientist’s shrinking machine.

“Colonel Locke,” the General said, “you remember Colonel March?”

“Sure,” he said. “How are you, Milo?”

“All right, I guess,” I said, “although I do feel a little like a pig starting up the first ramp in the slaughterhouse.”

“Why don’t you sit down, March,” the General said. “Then I’ll tell you both why you’re here.”

Locke and I looked at each other and shrugged. I sat down and the dog made a small noise in his throat.

“It’s all right, fella,” I said. “I’m a friend.” I looked inquiringly at Locke. “What happened to Dante?”