21,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

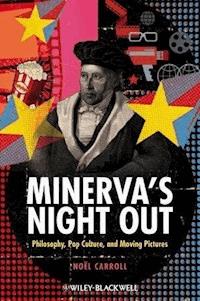

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Minerva’s Night Out presents series of essays by noted philosopher and motion picture and media theorist Noël Carroll that explore issues at the intersection of philosophy, motion pictures, and popular culture.

- Presents a wide-ranging series of essays that reflect on philosophical issues relating to modern film and popular culture

- Authored by one of the best known philosophers dealing with film and popular culture

- Written in an accessible manner to appeal to students and scholars

- Coverage ranges from the philosophy of Halloween to Vertigo and the pathologies of romantic love

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 810

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

Contents

Acknowledgments

Introduction: Philosophy and the Popular Arts

Notes

Section I: The Philosophy of Mass Art

1 The Ontology of Mass Art

I. The definition of mass art

II. The ontology of mass art

III. Objection #1: All art is multiple

IV. Objection #2: Mass art is irrelevant

Notes

2 Modernity and the Plasticity of Perception

Notes

3 The Ties that Bind

The issues

Identification

Simulation

Sympathy

Mirror reflexes

Summary

Notes

4 Character, Social Information, and the Challenge of Psychology

I. Introduction

II. Aristotle, poetry, and character

III. Social psychological skepticism about character

IV. A defense of a modified version of the common view

V. The Big Country

VI. Summary

Notes

Section II: The Philosophy of Motion Pictures

5 Movies, the Moral Emotions, and Sympathy

I. Introduction

II. Emotions and movies

III. The moral emotions and the audience’s response to movie characters, actions, events, and scenes

IV. Sympathy/antipathy, morality, and the movies

V. Concluding remarks

Notes

6 The Problem with Movie Stars

Introduction

The problem

Film, photography, and allusion

The movie star as allusion

Summary

Notes

7 Cinematic Narrative

References

Further Reading

8 Cinematic Narration

References

Further Reading

9 Psychoanalysis and the Horror Film

Notes

References

Section III: Philosophy and Popular Film

10 Philosophical Insight, Emotion, and Popular Fiction

Introduction

Sunset Boulevard

How can Sunset Boulevard be philosophical?

Summary

Notes

References

11 Vertigo and the Pathologies of Romantic Love

Aristotle, philosophy, and drama

Love and fantasy

Falling in love

Knots

Notes

12 What Mr Creosote Knows about Laughter

To laugh, or to scream?

Who’s afraid of Mr Creosote?

Just desserts

Notes

13 Memento and the Phenomenology of Comprehending Motion Picture Narration

Introduction

On the possibility of movie-made philosophy

Memento and the Art Cinema

Memento and narrative comprehension

Concluding remarks

Notes

References

Further reading

Section IV: Philosophy and Popular TV

14 Tales of Dread in The Twilight Zone

Introduction

Tales of dread: some examples from The Twilight Zone

The nature and function of Tales of Dread

Horror fictions and tales of dread: a brief note

Notes

15 Sympathy for Soprano

Sympathy for the devil

It was fascination

Wish fulfillment

Identification

Paradox solved

A remaining problem

Notes

16 Consuming Passion Sex and the City

I. Introduction

II. Consumerism

III. Ethics and the evils of consumerism

IV. Consumerism and the mass media

V. Sex and the City

VI. “A Vogue idea”

VII. Lighten up

VIII. Summary

Notes

Section V: Philosophy on Broadway

17 Art and Friendship

Notes

18 Martin McDonagh’s The Pillowman, or The Justification of Literature

Notes

Section VI: Philosophy across Popular Culture

19 The Fear of Fear Itself

Halloween: the festival of the wandering undead

The paradox of halloween

A psychoanalytic solution

The meta-fear of fear

Notes

20 The Grotesque Today

Notes

21 Andy Kaufman and the Philosophy of Interpretation

I. Introduction

II. Actual Intentionalism

III. Hypothetical intentionalism

IV. The case of Andy Kaufman

V. Hypothetical intentionalism again: the second round

VI. Conclusion

Notes

Index

This edition first published 2013© 2013 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons, in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell.

Registered OfficeJohn Wiley & Sons, Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

Editorial Offices350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UKThe Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell.

The right of Noël Carroll to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author(s) have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services and neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for damages arising herefrom. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Carroll, Noël, 1947–Minerva’s night out : philosophy, pop culture, and moving pictures / Noël Carroll. pages cmIncludes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4051-9389-4 (pbk.) – ISBN 978-1-4051-9390-0 (hardback)) 1. Motion pictures–Philosophy. I. Title. PN1995.C35575 2013791.4301–dc23

2013018957

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Cover image: Popcorn © Christopher Carder / istockphoto; Composition with cinema symbols © elapela / istockphoto; Abstract cinema background © PixelEmbargo / istockphoto; Superstar Background © Matthew Hertel / istockphoto; Hegel © Classic Image / AlamyCover design by Simon Levy, www.simonlevy.co.uk

To Kayla Carroll DownesFor the future

Acknowledgments

The author and publisher gratefully acknowledge the permission granted to reproduce the copyright material in this book:Chapter 1. “The Ontology of Mass Art,” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism55(2) (1997): 187–99.Chapter 2. “Modernity and the Plasticity of Perception,” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism59(1) (2001): 11–17.Chapter 3. “On the Ties that Bind: Characters, the Emotions, and Popular Fictions,” in William Irwin and Jorge Gracia (eds.), Philosophy and the Interpretation of Popular Culture (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2007), pp. 89–116.Chapter 4. “Character, Social Information, and the Challenge of Psychology,” in Garry Hagberg (ed.), Fictional Characters, Real Characters: The Search for Ethical Content in Literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, forthcoming).Chapter 5. “Movies, the Moral Emotions, and Sympathy,” Midwest Studies in Philosophy 34(1) (2010): 1–19.Chapter 6. “The Problem with Movie Stars,” in Scott Walden (ed.), Photography and Philosophy (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008), pp. 248–64.Chapter 7. “Narrative,” in Paisley Livingston and Carl Plantinga (eds.), The Routledge Companion to Philosophy and Film (London: Routledge, 2009), pp. 207–16.Chapter 8. “Narration,” in Paisley Livingston and Carl Plantinga (eds.), The Routledge Companion to Philosophy and Film (London: Routledge, 2009), pp. 196–206.Chapter 9. “Psychoanalysis and the Horror Film,” in Steven Jay Schneider (ed.), Horror Film and Psychoanalysis: Freud’s Worst Nightmare (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), pp. 257–70.Chapter 10. “Philosophical Insight, Emotion, and Popular Fiction: The Case of Sunset Boulevard,” in Noël Carroll and John Gibson (eds.), Narrative, Emotion, and Insight (University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 2011), pp. 45–68.Chapter 11. “Vertigo and the Pathologies of Romantic Love,” in David Baggett and William A. Drumin (eds.), Hitchcock and Philosophy (Chicago: Open Court, 2007), pp. 101–13.Chapter 12. “What Mr. Creosote Knows about Laughter,” in Gary L. Hardcastle and George A. Reisch (eds.), Monty Python and Philosophy (Chicago: Open Court, 2006), pp. 25–35.Chapter 13. “Memento and the Phenomenology of Comprehending Motion Picture Narration,” in Andrew Kania (ed.), Memento (London: Routledge, 2009), pp. 127–46.Chapter 14 “Tales of Dread in The Twilight Zone: A Contribution to Narratology,” in Noël Carroll and Lester Hunt (eds.), Philosophy in “The Twilight Zone” (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009), pp. 26–38.Chapter 15. “Sympathy for the Devil,” in Richard Greene and Peter Vernezze (eds.), The Sopranos and Philosophy (Chicago: Open Court, 2004), pp. 121–36.Chapter 16. “Consuming Passion: Sex and the City,” Revue internationale de philosophie 64(254) (2010): 525–46.Chapter 17. “Art and Friendship,” Philosophy and Literature 26(1) (2002): 199–206.Chapter 18. “Martin McDonagh’s The Pillowman, or The Justification of Literature,” Philosophy and Literature 35(1) (2011): 168–81.Chapter 19. “The Fear of Fear Itself: The Philosophy of Halloween,” in Richard Greene and K. Silem Mohammad (eds.), Zombies, Vampires, and Philosophy (Chicago: Open Court, 2010), pp. 223–35.Chapter 20. “The Grotesque Today: Preliminary Notes toward a Taxonomy,” in Frances S. Connelly (ed.), Modern Art and the Grotesque (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), pp. 291–311.Chapter 21. “Andy Kaufman and the Philosophy of Interpretation,” in Michael Krausz (ed.), Is There a Single Right Interpretation? (University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 2002), pp. 319–44.Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologizes for any errors or omissions in the above list and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

Introduction

Philosophy and the Popular Arts

As long as it is not frightfully bad, [a film] always provides me with food for thoughts and feelings.

Ludwig Wittgenstein1

This volume represents a selection of my essays on philosophy and the popular arts – including philosophy of, in, and through various popular art forms. Motion pictures, my first love, have an especially prominent place in what follows. I have been particularly lucky that I became a philosopher at a moment when it became acceptable to engage with the popular arts theoretically. It would probably have been impossible for an analytic philosopher do so anytime before World War II and maybe even before the Vietnam War.

But for at least several decades now, within the precincts of anglophone philosophy, interests of various sorts in the popular arts have grown in every direction and at a fast pace as presently evidenced by whole book series devoted to philosophy and the popular arts, such as those published by Wiley-Blackwell and Open Court. Perhaps the phenomenon first gained a substantial foothold among English-speaking philosophers with respect to film, not merely art films, but mass market entries as well. Then popular music enlisted philosophical respect, followed by TV, and now the vista is wide open, countenancing everything from comics and talent shows to video games.

Speaking from the perspective of the United States, this seems to be a predictable outcome of certain demographic trends. The post-World War II baby boomers as a group – of which I am a card-carrying member – were probably more involved with the mass, popular arts than any other previous generation. Owing to things like television and portable radios, for example, we have had more access to mass art than the preceding generations and, in all likelihood, more leisure time to pursue it as well.

We have been immersed in mass art. If Homer, despite Plato’s deprecations, was the educator of the Greeks, mass art was the educator of the Americans, or at least those of my generation (and those that followed). Thus, it should have come as no surprise that we took our first, so to say, common culture very seriously. Surely, that is one of the reasons that when we came of age we were so invested in expanding the study of what was effectively our lingua franca. And, of course, nothing that stood so squarely in the center of our culture could escape the notice of philosophy. Our students and then theirs have benefited our obsessions with mass entertainments which have permitted them to write dissertations on topics that would never have been admitted into academia before the Vietnam War.

Among the mass arts that commanded the attention of the baby boomers, the moving image was among the most powerful, perhaps because constant reruns on TV of classic and not so classic Hollywood films gave us access to the tradition in a way that had not been available to the preceding generation. Moreover, our will to take movies in earnest was, by the time we were entering adolescence, given the intellectual wherewithal to make our wishes come true by several important developments, including the emergence of European and Japanese art films, which demonstrated that some films were worth taking seriously artistically, while the French auteur theory gave us the rhetoric to argue that some Hollywood films were among those movies worth taking seriously.

Thus, we began treating cinema with respect – by, among other things, inaugurating academic film departments – and, once the moving image became not only a legitimate topic of inquiry but a substantial one, cinema began to invite philosophical inquiry, serving as a runway off which the owl Minerva could take flight. The philosophical scrutiny of other mass arts ensued in short order.

Within the context of Anglo-American philosophy, one of the crucial figures who opened up the popular arts to philosophical interrogation was Stanley Cavell. By his own account, his reading of Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations liberated him through “its demonstration or promise that I can think philosophically about anything I want or have to think about.”2 Not only did Wittgenstein encourage Cavell’s embrace of ordinary language philosophy. From thence Cavell became the philosophical apostle of the ordinary, of which the ordinary experience of the popular arts, most notably film, was an ordinary part of the American experience. From his chair in the Harvard philosophy department, Cavell’s publications, including The World Viewed and Pursuits of Happiness, announced to the generation of his students and beyond that the popular arts were now a suitable topic of philosophy.3

Philosophical interest in the popular arts can take a number of different forms. I have entitled this introduction “Philosophy and the Popular Arts.” But in truth the conjunction and masks a series of different relations describable by the prepositions “against,” “in,” “of,” and “through.”

Arguably, most of the encounters between philosophy and the popular arts – from Plato to Adorno – were of the order of the “philosophy against popular art” variety. The popular arts were charged with perpetrating all sorts of social diseases from undermining the state by arousing the emotions to maintaining the regime of capitalist system by stupefying the minds of the masses. Of the essays in this volume, my “Consuming Passion” comes closest to this category, although, unlike Plato and Adorno, I am not chastising all popular art, but only a specimen thereof, namely Sex in the City.

Under the rubric of philosophy in popular art, I include philosophical interpretations of popular artworks that maintain that a given work either illustrates or otherwise articulates some pre-existing philosophical idea as one might argue Chaplin’s Modern Times illustrates Marx’s notion of the alienation of labor or The Matrix serves to motivate Cartesian skepticism. In this volume the essay “Art and Friendship” exemplifies this tendency by discovering Aristotle’s view of the highest form of friendship in Yasmina Reza’s play.

The philosophy of popular art is a much more straightforward animal. It takes the popular arts and its various forms – movies, TV, theater and so forth – as its object of study. It probes the nature of such things as mass art in terms of the relationship of audiences to the characters of popular fictions, the nature of popular narratives and various popular genres and the structures therein, as well as the problems and paradoxes raised by the popular arts, including ethical ones. I reckon that more essays of this sort populate this collection than essays of any of the other categories in the philosophy and popular arts neighborhood.

The second largest group of essays in this volume probably belong to the category of philosophy through popular art. Roughly, this category regards the popular arts, or at least certain particular examples of popular art as capable of doing philosophy – as not only framing philosophical questions and inviting audiences to grapple with them, but also sometimes joining in the philosophical debate and advancing considerations on behalf of the philosophical conclusions they endorse.

Of course, not all philosophers believe that it is possible for any popular artwork to do philosophy, properly so called. So, whether the category of philosophy through popular art has any members is itself a philosophical question. This controversy has been staged most vociferously with respect to motion pictures. Thus the essays in this volume about motion pictures, including popular films and avant-garde ones, return to this question often. A range of different arguments and counter-arguments are raised both in terms of what I call popular philosophy, but also in terms of the level of philosophy we bandy about in our seminar rooms.

Because there are examples of all the various sorts of relationships between philosophy and popular art in this volume, and especially because there are mixtures thereof in individual essays, I thought that a more perspicuous way of organizing the text would be in virtue of the media and genres in which philosophy and the popular arts come together, rather than in terms of relationships as recounted above.

Hence, I begin with a section on “The Philosophy of Mass Art.” The reason that I have started with mass art rather than popular art is because most of the popular art discussed in this book – indeed, most of the popular art consumed nowadays – is mass art (understood as a subcategory of popular art).

As previously mentioned, motion pictures probably comprise the domain of mass art that has attracted the most philosophical attention. For that reason, the next section of the volume concerns “The Philosophy of Motion Pictures.” Within the larger category of motion pictures, I include not only mass market movies, but popular TV. Consequently, the next two sections of this book are “Philosophy and Popular Film” and “Philosophy and Popular TV.”

Perhaps needless to say, not all popular art is mass art. Broadway theater is popular, but it is not available at multiple reception sites in the way a movie is. Nevertheless, mainstream theater is a place where philosophy and popular art meet, as in the case of Copenhagen, not to mention many of the plays of Bertolt Brecht and Tom Stoppard. Thus I have included a section on relations between theater and philosophy in which I look at Yasmina Reza’s Art and Martin McDonagh’s The Pillowman.

The last section in this volume is entitled “Philosophy across Popular Culture” because it takes up topics that sometimes cross not only the distinction between mass artworks and singular artworks, like stand-up comic performances, but as well practices of popular culture, like Halloween, that are not reducible to popular art.

Undoubtedly, these section headings are not as exclusive as they might be. To some degree, the choice of placing one article here rather than there may be arbitrary. Nevertheless, all the articles belong together. They all celebrate the way in which art stimulates the sort of pleasures that are associated with philosophy where philosophy itself is fun. In short, Minerva’s nights out turn out to be like Minerva’s nights in at work at home – a matter of entertaining ideas.

Notes

1 Ludwig Wittgenstein, Public and Private Occasions, trans. James Klagge and Alfred Nordman (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2003), p. 97. Also cited by Béla Szabados and Christina Stojanova in “Introduction,” Wittgenstein at the Movies: Cinematic Investigations (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2011), p. ix.

2 Stanley Cavell, “Introductory Note to “The Investigations’ Everyday Aesthetics of Itself,” in John Glbson and Wolfgang Huemer (eds.), The Literary Wittgenstein (London: Routledge, 2004), p. 181. Also cited by Andrew Kleven in “Notes on Stanley Cavell and Film Criticism,” in Havi Carel and Greg Tuck (eds.), New Takes in Film-Philosophy, (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), p. 62.

3 I have heard an anecdote, which is probably apocryphal, that Sartre became attracted to phenomenology when he learned that it would enable him to philosophize about a cocktail. This desire to philosophize about ordinary, contemporary experience, as manifested by Sartre and Cavell, has become rampant among the last three generations of American philosophers.

Section I

The Philosophy of Mass Art

1

The Ontology of Mass Art

If by “technology,” we mean that which augments our natural powers, notably those of production, then the question of the relation of art to technology is a perennial one. However, if we have in mind a narrower conception of technology, one that pertains to the routine, automatic, mass production of multiple instances of the same product – be they cars or shirts – then the question of the relation of art to technology is a pressing one for our century. For in our century, especially, traffic with artworks has become increasingly mediated bytechnologies in the narrower (mass production/distribution) sense of the term. A technology in the broad sense is a prosthetic device that amplifies our powers.1In this respect, the technologies that mark the industrial revolution are prostheses of prostheses, augmenting the scope of our already enhanced powers of production and distribution through the automatization of our first-order technical means. Call such technologies “mass technologies.” The development of mass technologies has augured an era of mass art, artworks incarnated in multiple instances and disseminated widely across space and time.

Nowadays it is commonplace to remark that we live in an environment dominated by mass art – dominated, that is, by television, movies, popular music (both recorded and broadcast), best-selling “blockbuster” novels, photography, and the like. Undoubtedly, this condition is most pronounced in the industrialized world, where mass art, or, if you prefer, mass entertainment, is probably the most common form of aesthetic experience for the largest number of people.2 But mass art has also penetrated the nonindustrial world as well, to such an extent that in many places something like a global mass culture is coming to co-exist, as what Todd Gitlin has called a second culture, alongside indigenous, traditional cultures. Indeed, in some cases, this second culture may have even begun to erode the first culture in certain Third World countries. In any case, it is becoming increasingly difficult to find people anywhere in the world today who have not had some exposure to mass art as a result of the technologies of mass distribution.

Nor is any slackening of the grip of mass art likely. Even now, dreams of coaxial cable-feeds running into every household keep media moguls enthralled, while Hollywood produces movies at a fevered pace, not simply to sell on the current market, but also in order to stockpile a larder sufficient to satisfy the gargantuan appetites of the home entertainment centers that have been predicted to evolve in the near future. Intellectual properties of all sorts are being produced and acquired at a delirious pitch in the expectation that the envisioned media technologies to come will require a simply colossal amount of product to transmit. Thus, if anything, we may anticipate more mass art everywhere than ever before.

However, despite the undeniable relevance of mass art to aesthetic experience in the world as we know it, mass art has received scant attention in recent philosophies of art, which philosophies appear more preoccupied with contemporary high art, or, to label it more accurately, with contemporary avant-garde art. Given this lacuna, the purpose of the present paper is to draw the attention of philosophers of art to questions concerning mass art, a phenomenon that is already in the forefront of everyone else’s attention.

The particular question that I would like to address here concerns the ontology of mass art – the question of the way in which mass artworks exist. Or, to put the matter differently, I shall attempt to specify the ontological status of mass artworks. However, before discussing the ontological status of mass artworks, it will be useful to clarify that which I take to be mass art. So, in what follows, I will first attempt to define necessary and sufficient conditions for membership in the category of mass art. Next, I shall introduce a theory about the ontological status of mass art. And finally, I will consider certain objections to my theories.

I. The definition of mass art

Perhaps the very first question that arises about my account of mass art concerns my reason for calling the phenomenon under analysis “mass art” rather than, say, “popular art.”3 My motivation in this regard is quite simple. “Popular art” is an ahistorical term. If we think of popular art as the art of the lower classes, then probably every culture in which class divisions have taken effect has had some popular art. On the other hand, if we think of popular art as art that many people in a given culture enjoy, then, it is to be hoped, every culture has some popular art. But what is called “mass art” has not existed everywhere throughout human history. The kind of art – of which movies, photography, and rock and roll provide ready examples – that surfeits contemporary culture has a certain historical specificity. It has arisen in the context of modern, industrial, mass society, and it is expressly designed for use by that society, employing, as it does, the characteristic productive forces of that society, viz., mass technologies, in order to deliver art to enormous consuming populations.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!