Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

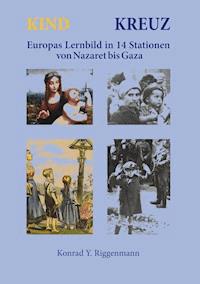

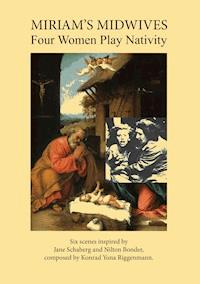

Based on diligent research, the seven scenes of this nativity play present a realistic, biblically evidenced and coherent but persistently denied reading of Jesus' coming into this world. His end as a victim of Roman soldiers in touching psycho-logics corresponds with his start in the womb of a young rural worker victimized by Roman soldiers. Far from blasphemy but full of sympathy with both victims, these scenes show that, in the wording of Brazilian Rabbi Nilton Bonder, "not force and virility but ... the woman builds the path of humanity" and that, in the words of Catholic US-theologist Jane Schaberg, the repressed tradition of Jesus' illegitimous birth "unmasked ... presents us with fuller human realities and therefore with deeper theological potential."

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 170

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

1943: Young Jewess abused by Ukrainian heroes but succoured by elder women.

Madonna of the yarnwinder, inspired by a lost painting of Leonardo, born on April 15, 1452 as son of a patrician with a rural worker named Catarina. Alessandro Vezzosi, founder of the Museo Ideal in Vinci, explains: “Many wealthy and prominent families bought women from Eastern Europe and Middle East. The young girls then got baptized, their most frequent names being Maria, Marta und Catarina.” A fingerprint of Leonardo showed a pattern normally found only among Arabs.1

1 “Da Vinci’s mother was a slave, Italian study claims.” The Guardian, April 12, 2008.

Inhaltsverzeichnis

On Historical Ground

Matthew: Jesus’ sinful grandmothers

Sired in violence

Luke: Rising from humility

Mark: Jesus ben Miriam

John: But you were!

Thomas: Son of the porné

Her repaired family

Whose backgrounds we don’t know

Toldoth Jeschu: Get out, you bastard!

Panthera the panther

Telling words of an intruded child

Jesus Bar Abbas

This conscious working toward death

Last and first: the women

End and beginning

On Stage

The three midwives on their way to Miriam

In Miriam’s house, in Miriam’s womb

Why didn’t you abort?

Miriam prophesies

God at trial

Delivery

Interaction with the audience

Postface

Bibliography

Sources of pictures and music

Sheet music

A On Historical Ground

Miriam’s Midwives give a down-to-earth answer to a high-flying text that began to dominate the West as from the encounter this same text describes as follows:

In the sixth month the angel Gabriel was sent by God to a town in Galilee called Nazareth, to a virgin engaged to a man whose name was Joseph, of the house of David. The virgin’s name was Mary. And having come in (εἰσελθὼν) to her he said: “Do not be afraid, Mary, for you have found favor with God. And now, you will conceive in your womb and bear a son, and you will name him Jesus. He will be great, and will be called the Son of the Most High, and the Lord God will give him the throne of his father David ...” Mary said to the angel: “How can this be, seeing I know not a man?” The angel said to her: “The holy spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you; therefore the child to be born will be holy; he will be called Son of God.” (Luke 1:30-35)

Below the angel and the God who sent him, the text speaks rather earthly, bodily: The virgin is afraid of one who comes in foreboding she will conceive. She is engaged to a man (1:26) but knows not a man. She doesn’t get asked; there is no bit of love, let alone of lust. Something strong will come upon her. Since this force will overshadow her (ἐπισκιάσει, episkiásei) it must be a darkening force. As to fathers, two are mentioned: David and God.

With literary finesse, the Greek-encultured author around 90 CE wraps into a God-fearing story the reality of a very unhoped-for yet occurring, a scaring because dark and encroaching conception without preceding love. And all this, as Luke confirms, by order of the godly Lord to whom a woman is not entitled to object. For his contemporary Greek and Roman readers who knew Zeus & Co. as very virile godheads and like them used to have a good grip on their women, this wasn’t overly offensive.

Two millennia later however the question arises which cultural side effects this primal scene had for the West. What, just for example, have the Christian depreciation of the body and of sexual nature (natura, the getting born), of keeping the celibate high and women low, to do with the model of the virginal obedient servant Mary?

The real weight of this primal scene however rises from the fact that the son proceeding from this scene became the paragon of obedience; that this image of his cross justifyingly accompanied the genocides on native Indians, Africans and Jews; that till this day it orients the most violent one of all continents and spreads the message of salutary, redeeming violence.

Exactly this sick message is what Miriam’s Midwives face in tracing back the allegedly voluntary world-redeeming violence of Jesus’ end to his beginning in his mother’s womb.

Russian Madonnas, Brazilian Christmas cribs and Italian Renaissance paintings visualize this onset-to-end-violence by placing next to this child, in the manger or on his mother’s lap, the cross on which the boy will die one day, according to his heavenly father’s divine planning.

In light of the awful violence at the end of his short life, Miriam’s Midwives should be allowed to link the Roman military violence in his killing with the one in his siring. For exactly the texts of that bible that made Miriam and Jesus world-famous also evidence that he was his mother’s illegitimous child.

“My son are you, today I have begot you”, God says to his Son, and he replies: “My father are you, my God.”

Who gives this answer? Jesus? No, King David is this Son of God, in Psalm 2:7 (cf. 89:27). Wait a minute, says the Christian: this king David is calling God his father but in the same sense as Jesus taught us to call this God “Our father”, right? But this way, dear Christian, things get even more complicated: If Jesus calls his Abba, Father the Our Father, what, then, distinguishes his sonship, his special relation to this Father from common people’s relation to Our Father? What distinguishes his cruel sacrifice from the awful deaths of so many of God’s children, for instance the 50,000-100,000 rebels killed on crosses during Roman occupation of Palestine or the 13 millions of Africans booked as losses on the way to the Christianized Americas or the 1,300,000 children filling fosses with their corpses because their ancestors had killed Jesus nineteen centuries ago?2

Let us hold that biblical texts present the son of a virgin and mother of seven (Mark 6:3) as a descendant of David as well as of God. What hides behind this Bar-Abbas triangle of a man with such strong a father-relation that Paul declared him the Son of the Most High?

For now and for good measure, let’s stay with Jesus Son of David, because herefore one can take both Old and New Testament as witnesses. In nice harmony, both of them – in the gospel of Matthew which quite literally is the bridge between them – point at four immoral acts of begetting, four improperly loving great grandmothers of King David, of the Messiah Jesus, son of Miriam.

Matthew: Jesus’ sinful grandmothers

“Book of descendance of Jesus Christ, the Son of David, the Son of Abraham: Abraham begot ...” and so on. This passage (Matthew 1), presenting the transition from the “Old Bible” to the “New Testament”, counts down 40 old ancestors of Jesus. But scanning this congregation of long-bearded patriarchs in detail, five female headscarfs gleam among them:

“Judah begat Perez and Zerah by Tamar ...”

“Salmon begat Boaz by Rahab ...”

“Boaz begat Jobed by Ruth ...”

“David begat Solomon by the wife of Uriah ...” whose name was daughter of Seba, Bathseba. And last not least:

“Jacob begot Joseph the husband of Mary, of whom was born Jesus, who is called Christ” (Matthew 1, verse 16). The husband of Mary who elsewhere and doctrinally rates but as Jesus’ stepfather is here the indispensable link in the genealogical chain from Abraham to Mary’s son. So was Jesus begot by Joseph ben Jacob? No, for immediately after the whole chain of ancestry follows the disclaimer: “When his mother Mary was betrothed to Joseph, it happened that she, before they lived together, had conceived from the Holy Spirit” (Matthew 1, verse 18). Now not from Joseph? By whose semen, then?

Textual contradiction or careless edition? One shouldn’t take Matthew, the probably only Jewish one of four gospel authors, for silly. Of course he was completely conscious of the contradiction within one and the same chapter of his text. Completely consciously he had copied the line of David’s forefathers from the first book of Chronicle (1-2) and modified the line of David’s offspring to get to a neat three-fold symmetry of 14 generations up to David, 14 up to Babylon and 14 from Babylon to Jesus – provided, however, that Mary is counted as a man’s equivalent. Matthew’s new edition is completely intentional. But what is his intention? Did he, who “writes among Jews for Jews”3 intend to appoint his Jewish readers, by introducing the four Davidian grandmothers, to an open secret in his Jewish ambience, a vital biographic detail of the fifth Jewish mother, Mary of Nazareth? What detail this might be, we can find out by taking a close look at the four uncommon women Tamar, Rahab, Ruth, Bathseba, those special mothers Matthew deemed worthy to stand in line with 40 virile patriarchs.

Tamar screws the chief: Jacob’s fourth son Judah had migrated to Canaan and become the husband of the Canaanite woman Shua in mixed marriage. She bore him three sons named Er, Onan and Shelah, who grew up to – so he hoped – give Judah grandsons, and “Judah took for his firstborn Er a woman named Tamar.” But Er dies early. Now the second son is obliged to marry the widow to deliver offspring to his dead and childless brother. Not very romantic, and no wonder Onan now starts to do not exactly what is termed referring to his name but coitus interruptus, every time, “and let his semen drop to earth.” Because this is not healthful and “Yahve disagreed of what he did”, Onan also dies. Now Tamar has to wait until Judah’s third son Shelah advances up to marriagable age to be given to her as her third husband. In vain she waits. Her father-in-law Judah, meanwhile a widower himself, makes no arrangements to give his third son to his two sons’ black widow. After the mourning period, widower Judah journeys to Timnah for sheep shearing. At the entrance to the village Enayim he catches sight of a veiled harlot, and for the price of a he-goat she agrees. But since he-Judah has no he-goat at hand, he asks the harlot if she will accept his signet-ring, cord and rod as pawns? Okay, she does, they do.

Three months later Judah gets alerted: “Your daughter-in-law has gone astray and become pregnant due to her sin.” Well, with such a woman the chief will make short trial: “Take her out. She shall be burnt!” But the condemned young woman puts three objects in front of the patriarch’s eyes: Signet-ring, cord and rod. Accused by those objective objects Judah confesses: “She’s in her right against me. Why did I not give her as his wife to my son Shelah?” (Gen 38). And the child of shame and incest is named Perez and becomes one of the Messiah’s great-grandfathers.

Rahab whores and helps: While Jesus’ Greatgreat~grandmother Tamar had to play the harlot just for a short time to win her case against the patron, his Great~grandmother Rahab is right in the service and probably not lacking clients in Jericho. Into this capital of Israel’s enemies, two spies are sent by Joshua son of Nun. They stay in Rahab’s house during the night but raise suspicions, so her compatriots ask the madam to bring forth her strange customers. They’re gone already, Rahab says, but if you hurry you’ll catch them! Alone again, she goes up to the roof where she has hid the two spies beneath stalks of flax. Here she begs them to swear that her father, her mother, her brothers and sisters will be treated mercifully when the city gets conquered. On a chord she lets the two James Bonds climb down out of the brothel’s window, “for her house was at the city’s wall (Joshua 2:15). Short time later, God’s people advances to take Jericho. Joshua orders the tabernacle to be carried seven times around the walls and seven priests to blow on seven ram horns; and on the seventh day at first the walls come tumbling down and second the citizens are slaughtered.

For the walls are falling down

And the town is flattened to the earth alike

But one cheap hotel is shunned from every strike

And they ask what VIP is living there?

And this very noon there will be silence in the harbour

When they ask themselves now: Who will have to die?

And then everyone will hear me saying: All them!

And when the head drops down I just say: Hoppla!

And the ship with eight sails and fifty big cannons

Will vanish with me.

No, Rahab doesn’t order “them all” to be killed and she doesn’t comment with Hoppla as Bertolt Brecht’s Pirate Jenny does. But Rahab-Jenny of Jericho, together with “her father, her mother, their brothers and all who belonged to her” is escorted from her happy house out to a “safe place” and she “remained living in Israel up to this day” (Joshua 6:25). In her new life Rahab the hooker first became an honest housewife, then a mother, grandma and Ruth’s second mother-in-law. Matthew has no problem integrating the former harlot into the Messiah’s maternal line: “Salmon begot Boaz from Rahab and Boaz begot Jobed from Ruth.”

Ruth pulls the honest whoreson: “In the days when the chieftains ruled, there was a famine in the land; and a man of Bethlehem in Judah, with his wife and two sons went to reside in the country of Moab”. The women of Moab, descending from Lot’s incest with his elder daughter (Gen 19:37), are famous for their beauty. No wonder that both sons of the migrant family marry soon, the happy brides’ names are Orpah and Ruth, but again both husbands die. Their father Elimelech had passed away yet before them, and his widow Naomi, having heard that in the land of Judah rain, milk and honey are flowing again, sets out to return to her people. Both daughters-in-law shed tears, “but Ruth clung to her” and insists on going with Naomi. “For wherever you go, I will go; wherever you lodge, I will lodge; your people shall be my people, and your God my God.”

Arrived in Bethlehem, Ruth takes on the kind of bread-winning open to the paupers: Gleaning ears of grain on harvested fields. All by chance she comes to the field of Boaz, who all by chance just arrives from Bethlehem and asks his reapers’ foreman: “Whose girl is that?” – “She is a Moabite girl who came back with Naomi”, the servant tells him. “She has been on her feet ever since she came this morning and rested but little in the hut.” Boaz is impressed with the Moabite belle’s good references. “Don’t go to glean in another field”, he greets her. “I have ordered the men not to molest you. And when you are thirsty, go to the jars and drink some water of that the men have drawn.” Mealtime gives occasion to get closer: “Come over and partake of the meal, and dip your morsel in the vinegar”, he invites her with lavish compliments of fragrant, crispy roasted grain.

When Ruth comes home to her mother-in-law at night with amourousness beaming out of every buttonhole, Naomi asks her knowingly: “Daughter, I must seek a home for you, where you may be happy. Now there is your kinsman Boaz, whose girls you were close to. He will be winnowing barley on the threshing floor tonight. So bath, anoint yourself, dress up ...” After the early summer work peak Boaz, son of Rahab, “ate and drank, and in a cheerful mood went to lie down beside the grainpile.” And so decently the Bible describes how a strong woman – all without seduction – gains her ends: “Then she went over stealthily and uncovered his feet and lay down. In the middle of the night, the man gave a start and pulled back – there was a woman lying at his feet! “Who are you?” he asks with male naivity. “I am your handmaid Ruth. Spread your robe over your handmaid, for you are a redeeming kinsman.” Boaz, however, is but the second-ranking redeemer, his obligation on his distant cousin’s inheritance including his widow depends from another kinsman’s will. When this first redeemer renounces, due to material considerations, on the economically unsexy match, Boaz marries Ruth “and the Lord let her conceive and she bore a son. Naomi is happy, gracefully listening to the women’s congratulations: “He will renew your life and sustain your old age; for he is born of your daughter-in-law, who loves you and is better to you than seven sons.”

The grace of female beauty – with which Tamar was blessed maybe poorly, Rahab profession-adequately and Ruth most surely – this attraction may be found in Jesus’ fourth foreign grandmother, at King David’s times, in most infatuating power:

Bathseba bathes and succumbs: “The woman was very beautiful” – the young woman whom King David, strolling on the roof of his royal palace, sees bathing in another man’s dominion. Spontaneously, the voyeur royale sends messengers to this cherry in neighbor’s garden; spontaneously he layes with her and she – having taken this fateful bath to purify herself after her period – conceives. In order to make the fruit of love appear legitimous, David orders her husband, General Uriah, to come home from military front and almost coerces him to meet his wife. But Uriah, too ascetic or too well informed, refuses and prefers to sleep outside the gate in his troop’s camp. Plan B: “Place Uriah in the front line where the fighting is fiercest”, David writes to Joab. “Then fall back so that he may be killed.”

And thus the angel of death meets Uriah, and David marries Bathseba, who now bears him a son. No sooner than wise Nathan tells the king a story of the “only one ewe lamb” heeded like a daughter by the poor man but slaughtered and put roasted on the table for his guest by the rich man (2 Sam 12:3), no sooner than David falls in rage against this man who “did this and deserves to die” and Nathan says: “That man is you!” – no sooner than now David breaks down, confesses, repents. Nathan, taking God’s position, replies: “The Lord has remitted your sin; you shall not die” – but the child will. David fasts, sleeps on the stone floor, and ends his self-punishment no sooner than on the seventh day, when his servants dare to tell him that the baby boy has died. “Now that he is dead, why should I fast? Can I bring him back again? I shall go to him, but he will never come back to me.” Then he consoled his wife Bathseba, he went to her and lay with her, she bore a son and named him Solomon.

Four Women, four questionable, but child-bearing encounters: Why did Matthew spread this four-cornered basis of Jesus’ maternal ancestry before he put Mary on top of it?

University of Detroit theologist Jane Schaberg emphasizes that all four prefigurants of Mary were born non-Jewish. “Rahab and probably Tamar were Canaanites, Ruth a Moabitess, and Bathseba probably a Hittite like her husband.” According to the later Jewish rule that became valid in Jesus’ times and based being Jewish on being born from a Jewish mother, the four women’s sons were not Jewish and nevertheless were to become Solomon’s forefathers.4 Mary, however, was a Jewess. Did Matthew want to intimate gently that this time not the mother, but the father was outlandish?

Jane Schaberg considers the four indecent women to have four common features;5 four similarities that I, taking into account especially the perspectives of Brazilian rabbi Nilton Bonder in his book “Our Immoral Soul”, will formulate with slight modifications:

All four find themselves outside patriarchal family structures, struggling with, and wronged or thwarted by, the male world’s rules: Tamar and Ruth are childless young widows who achieve their rights by seducing elder men; Rahab a prostitute who achieves to safe her family just by her male-dominated, males-dominating profession; Bathseba is an adulteress between two warriors, and then a widow pregnant with her lover’s child, advancing her lively inheritance into the center of social power.

In their sexual activity all four risk damage to the social order and their own condemnations.