Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

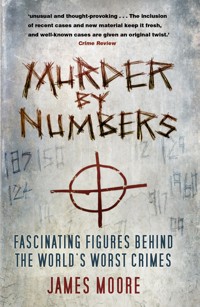

What's the connection between the number 13 and Jack the Ripper? Why is the number 23 of note in the assassination of Julius Caesar? And what is so puzzling about the number 340 in the chilling case of the Zodiac Killer? The answers to all these questions and many more are revealed in this unique, number crunching history of the ultimate crime. Packed with 100 entries ranging from 1 to 1 billion, Murder by Numbers tells the story of murder in an entirely new way – through the key digits involved. Discover why the length of a bath was critical to convicting a killer, how the weight of a trunk helped police crack a case and why a fake house number was central to a seemingly unfathomable murder mystery. Full of astonishing figures, from fatal doses of poison to grizzly death tolls, this gripping armchair guide also covers scores of famous cases such as the Black Dahlia, Acid Bath Murderer and Yorkshire Ripper. Featuring murders involving Al Capone, Bonnie and Clyde, Neville Heath, Lord Lucan, Ted Bundy, Harold Shipman and even Adolf Hitler, this is a must for true crime addicts, history buffs or anyone who has ever longed to solve a classic 'whodunit'.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 411

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2018

This paperback edition published 2019

The History Press

97 St George’s Place

Cheltenham, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© James Moore, 2018, 2019

The right of James Moore to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 8707 3

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction

MURDER BY NUMBERS

Select Bibliography

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Numerous people gave their help and support to make this book possible, but I’d particularly like to thank Tamsin Moore, Laurie Moore, Alex Moore, Philippa Moore, Geoffrey Moore, Sam Moore, Dr Lana Matile Moore, Dr Tom Moore, Dr Claire Nesbitt, Jan Hebditch, Daniel Simister, Sarah Sarkhel, Jim Addison, Samm Taylor, Judi James, Peter Spurgeon, Fran Bowden, Martin Phillips, Robert Smith and Mark Beynon.

James MooreGloucestershire, 2017

INTRODUCTION

Sherlock Holmes was obsessed by numbers. ‘It is a simple calculation enough,’ he said, while explaining one of his conclusions in A Study in Scarlet, the first of Arthur Conan Doyle’s works to feature the great fictional detective. In the story, Holmes works out the height of a man from measuring the length of his stride and the writing on a wall, while estimating his age from the size of a puddle over which he has jumped. Numbers run through his adventures from the mysterious ‘five orange pips’ to the bizarre smashing of the ‘six busts of Napoleon’. Even the number of the address at which Holmes lived, 221B Baker Street, has become world famous. His most notorious foe, Moriarty, was a master mathematician.

Agatha Christie, who gave us Miss Marple and Hercule Poirot, loved numbers too. Her most acclaimed novel, And Then There Were None, revolves around the number ten in a tale that chillingly parallels the fate of those in the nursery rhyme ‘Ten Little Indians’. In 2015 a group of scientists even collected data on methods, motives and locations from twenty-six of Christie’s works and were able to come up with a formula enabling readers to identify who the culprit is before the author herself reveals the killer. Among the fascinating findings was that if the setting was a country house there was a 75 per cent chance the murderer would be female.

Numbers also provide the key to real-life crimes, especially murders. This book examines in thrilling, and often graphic, detail how numbers provide the backdrop to some of the most fascinating cases from history.

Motives for murder may often involve sex or revenge, but money is often at the root of homicide, and whether the numbers involved are small or large, they can be both shocking and revealing – often giving police vital leads too.

From the moment a murder is committed, numbers are at the heart of any investigation. In forensics, medical examiners aim to identify the time of death, looking at factors such as body temperature and rigor mortis. They determine the number of wounds on a victim and perhaps their length and depth, as well as taking the physical measurements of the corpse and estimating the person’s age. All these are recorded in digits.

In murders involving firearms, ballistics experts may seek to identify the calibre of a weapon used or calculate the angle of trajectory at which a bullet struck its victim. They use mathematical formulas to calculate the twist of the barrel and might even weigh ammunition, looking for vital information.

Toxicology tests can reveal how much poison is in a body, while measuring hairs or fibres found at a murder scene can be highly revealing, as can figures relating to the distribution of blood. Even shoe size or, for that matter, the age of pollen on an item of footwear, can reveal an important number. So can the length of time insects have been at work on a body. DNA evidence can provide startling statistics when it comes to determining whether an individual should be ruled in or out of an enquiry.

Detectives also pore over numbers as they try and crack cases, studying the measurements taken at a crime scene, for instance, to get a picture of what happened. They’ll log timings of a victim’s or suspect’s movements too. They may seek to discover the number of victims linked to a single killer or note the typical height or age of victims when analysing a murderer’s modus operandi. Knowing the murderer’s own age and build could be equally crucial to tracking them down.

Numbers found on cars, weapons, clothes, tickets or phones can often provide the important breakthroughs in investigations. Then there are the numbers that reveal the scale of police enquiries – interviews conducted, calls logged, fingerprint records checked and so on.

The influence of numbers does not end when the investigation is wrapped up. Numbers continue to be vital when it comes to proving a case in court, with juries asked, for example, to weigh up probabilities expressed in numbers as they make their deliberations about whether the accused is guilty. Even where someone has been condemned to death, their executioners may have had to make careful calculations to ensure a swift and ‘humane’ death.

Sometimes, the startling figures in murder stories relate to how long it has taken for a body to come to light or the length of time it has taken to find the culprit. Often, despite the best efforts of investigators, cases continue to go unsolved, leaving behind only the stark and intriguing numbers involved.

Certain murderers have even been obsessed with particular numbers, while other cases are bound up with mysterious numerological associations. Occasionally, numbers reveal disturbing and puzzling coincidences between crimes.

Murder by Numbers looks at some of the fascinating statistics behind the phenomenon of murder, including its incidence as well as the nature of killers and their victims. It has been estimated that the number of people who have ever lived is around 108 billion. No one knows exactly how many of those have been murdered, but according to the World Health Organisation, in modern times a person is murdered every sixty seconds. This book covers hundreds of specific murders from across the centuries – a selection that affirms Sherlock Holmes’ sage observation that when it comes to crime, ‘There is nothing new under the sun, it has all been done before.’

1…

the world’s first murder

According to the Bible, the world’s first murderer was Cain, the son of Adam and Eve, who slew his own brother Abel in cold blood:

Now Cain said to his brother Abel, ‘Let’s go out to the field.’ While they were in the field, Cain attacked his brother Abel and killed him.

Genesis 4:8

The story goes that Cain, a farmer, and Abel, a shepherd, both made sacrifices to God, but that the Almighty favoured Abel’s. A furious Cain then murdered his brother.

Science, however, has highlighted other early victims of intentional slaughter going right back to our ancient ancestors. In 1991 a mummified body was found in melting ice high in the Italian Alps. It was originally thought to have been of a dead mountaineer. On closer examination by experts, the corpse turned out to be more than 5,000 years old. Dubbed ‘Ötzi the Iceman’, this Bronze Age body was remarkably well preserved, allowing numerous tests to be undertaken. Initially it was thought that Ötzi might have frozen to death, but thanks to a CT scan it emerged that he had an arrow wound in his left shoulder. Further analysis showed that the victim had also suffered a blow to the head and appeared to have suffered defensive injuries to his hands.

Whether Ötzi died from the head injury or bled to death, he had clearly met a violent end at the hands of another. But his was by no means the first homicide. Archaeologists have found evidence of the slaying of a Neanderthal male who lived around 50,000 years ago. Known as ‘Shanidar-3’, the victim had a cut on one of his left ribs that suggests that he was intentionally killed with a spear. An even earlier murder victim appears to have been found buried deep in Spain’s Atapuerca Mountains at a location known as the ‘pit of bones’. This cavern is located down a 43ft chimney only accessible after scrambling through a cave system. Over a twenty-year period, painstaking excavations have so far unearthed the remains of twenty-eight skeletons at the site belonging to the species Homo heidelbergensis, an early human ancestor pre-dating the Neanderthals.

One skull, belonging to a young adult and dating back some 430,000 years, was carefully reassembled from fifty-two separate pieces. Cranium 17 turned out to be of particular fascination when it was found to have two gaping holes above the left eye socket. Scientists applied modern forensic techniques, including 3D imaging and a CT scan, to the skull and compared the fractures to modern cases of injury. They determined that the wounds had occurred before death but that they did not seem to have been the result of a fall. Nor did they show any signs of healing. The holes were a similar shape and seemed to have been inflicted with a blunt instrument striking at different angles. These multiple blows suggested violence administered face-to-face. Either strike, perhaps by a wooden spear or stone hand-axe, would probably have been fatal. The conclusion was that the victim was intentionally hit twice over the head before being purposely plunged down the hole. This, the earliest case of homicide so far identified, suggests that murder was a behaviour associated with our earliest origins.

Recognition that the crime was something abhorrent goes a long way back too. The earliest-known recorded law against murder comes from the Sumerian Code of Ur-Nammu, set down on clay tablets sometime between 2100 and 2050 BC. It states that ‘If a man commits a murder, that man must be killed.’ The earliest recorded murder trial comes from another clay tablet dating to just a little later, 1850 BC. It was recovered from the same region of modern-day Iraq and reveals that three men, from the city of Nippur, were accused of murdering a temple official. They told his wife that her husband was dead, but perhaps under pressure, she stayed quiet about the crime. Somehow the killing came to light. The case was first brought before King Ur-Ninurta, who sent the three culprits and the woman for trial in front of the Citizens Assembly in Nippur. There was much debate as to whether the woman was guilty as an accessory. In the end, however, it was only the three men who were found guilty of murder and executed. Symbolically, their punishment was carried out in front of a chair belonging to the dead man.

One of the first murder victims we can name is the pharaoh Rameses III, whose throat was cut by an assassin in 1155 BC. Before long, cases of serial killers were being recorded too. Roman writer Pliny the Elder recorded that, in 56 BC, Calpurnius Bestia was accused of murdering a string of wives by rubbing the poison aconite into their genitalia. In the same era, in what is modern-day Sri Lanka, Queen Anula of Anuradhapura poisoned several husbands who weren’t to her liking, and was eventually burned alive for her crimes. A man from Yemen, Zu Shenatir, is known to have raped a series of young boys in the fifth century AD, after luring them to his house with promises of food and money. He then threw them to their deaths out of a window. Shenatir’s killing spree ended when one boy, named Zerash, managed to stab him before avoiding the same fate.

Cain and Abel. (Courtesy of Wellcome Library, London)

2…

missing bodies, in the case of the ‘Princes in the Tower’

During July 1674 workmen were demolishing a ruinous turret and staircase at the Tower of London. In the rubble, at the foot of some old stairs once used as a private entrance for the royal chapel, they found an intriguing wooden chest. Inside were two skeletons, seemingly of two young boys. One would have stood about 4ft 10in tall; the other, 4ft 6in. Still clinging to the bones were traces of aristocratic velvet. Word soon went round that these were the remains of murdered royalty.

Following the death of Edward IV in 1483, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, had seized the throne of England, while his nephews, the 12-year-old Edward V and 9-year-old Richard, Duke of York, were thrown in the Tower of London, never to be seen again. After Richard III himself was killed at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485, his successor, Henry VII, let it be known that the princes had been killed on Richard’s orders. Indeed, Tudor writer Thomas More said that one of Richard’s men, Sir James Tyrrell, had confessed to carrying out the crime before his execution for treason in 1502. More had even given a clue as to the whereabouts of the bodies, stating that they were buried at the foot of a set of stairs under some stones. Now, it appeared, they had turned up after nearly 200 years.

Physicians who examined the skeletons on behalf of Charles II pronounced that they were indeed the princes, and the king ordered that the bodies be interred in a marble urn at the Henry VII Lady Chapel in Westminster Abbey. But that wasn’t the end of the story. In 1933, under pressure from those who believed Richard III was innocent of the murder, the authorities agreed that the bodies could be disinterred and examined. Two medical experts found that the bones matched the ages of the princes at the time of their disappearance and that the velvet found with them was from the correct period. They also found evidence that the older individual had been suffering from an infection of the jaw (Edward was known to be unwell) and even that he might have been suffocated. They could not, however, establish the gender of the bodies, and subsequent analysis of the findings in the 1950s led to scepticism about their conclusions. By this time the bodies had been reinterred, and despite a more recent campaign for the bones to undergo DNA testing, both the Church of England and the Queen have refused permission for further forensic analysis, leaving their identity – and the exact fate of the boys – a much-debated mystery.

The Princes in the Tower. (Courtesy of Wellcome Library, London)

The disappearance of the princes remains the ultimate cold case. But it is not the only instance where murder has been assumed, and a culprit accused, without a body. Indeed, there have been many convictions in the absence of a corpse. In the United States there have been more than 250 trials without a body, dating as far back as 1843 when several crew members of the ship Sarah Lavinia were found guilty of throwing shipmate Walter Nicoll overboard.

In Britain, however, one infamous seventeenth-century scandal meant that the presence of a cadaver would effectively become an essential prerequisite in order to prosecute murder for three centuries. On 16 August 1660, 70-year-old estate manager William Harrison set out from his home in Chipping Campden, Gloucestershire, to collect rents at a nearby village. When Harrison failed to return home that night, his wife sent servant John Perry to look for him. It seemed there was no trace of Harrison, apart from some bloodstained clothes found on a nearby road. When suspicion fell on Perry himself, he suddenly accused his own brother and mother of murdering Harrison for money. A year later all three were found guilty and hanged for the crime. Yet, in 1662 Harrison sensationally turned up alive, claiming to have been abducted and sold into slavery.

The ‘Campden Wonder’, as it became known, led to the adoption of a ‘no body rule’, but that began to change in the twentieth century. A landmark case in 1954 concerned decorated Polish soldier Michael Onufrejczyk, who had decided to stay in Britain after the Second World War and run a farm. He took on fellow Pole Stanislaw Sykut as a business partner. But when the pair fell out over money, Sykut mysteriously vanished from the property. Onufrejczyk maintained that Sykut had returned to Poland. Suspicious, police found 2,000 tiny bloodstains at the farm, but no body. Nevertheless, amid rumours that Sykut had been slain and fed to the farm pigs, Onufrejczyk was charged with the killing and convicted of murder, going on to serve a life sentence.

The ensuing decades have seen many more convictions in cases without a corpse, but there have continued to be some notable miscarriages of justice too. In 1982 Lindy Chamberlain was convicted of murdering her 9-week-old daughter Azaria in the Australian Outback despite her pleas that a dingo had taken the baby. In 1987 she was given a pardon after some of Azaria’s bloodied clothing was found near a dingo’s den. Those who believe Richard III did not slay the princes in the tower are still hopeful that new evidence might emerge to clear the monarch of murder.

3…

times that murderer John Lee was unsuccessfully hanged

Many people have got away with murder over the centuries, but some evaded the death penalty even after being caught and convicted. In the past a killer could be given a reprieve if their execution failed, with the event usually deemed to be a sign of divine intervention. There was, for instance, the case of Maggie Dickson, hanged in Edinburgh for infanticide in 1724. She was left dangling from the end of a rope for thirty minutes, but for some reason had survived the ordeal. Maggie was later found to be alive, after knocking was heard from inside her coffin. She was given a full pardon.

Like all forms of capital punishment, hanging is, of course, an expert business, and even by the nineteenth century professional executioners could get things badly wrong. James Berry hanged 131 people during his time as an official public executioner and helped refine the so-called ‘long drop’ method, where the height and weight of the condemned individual were taken into account in order to establish how much slack would be needed in the rope to break their neck. This was deemed a ‘cleaner’ end than death by strangulation, which was often the result of a hanging. However, the long drop technique was still in its infancy. In November 1885, Berry oversaw the hanging of wife murderer Robert Goodale at Norwich, but the calculations were flawed and the culprit was decapitated by the rope.

It was a very different problem that had led to the botched execution of convicted murderer John Lee earlier the same year, with Berry again overseeing proceedings. Lee, 20, had been found guilty of slitting the throat of his employer, Emma Keyse, at her home in Babbacombe, Devon – albeit on flimsy evidence. He was due to be hanged on 23 February at Exeter Prison, and Berry duly tested his equipment beforehand, including the trapdoor through which Lee was set to plunge. As was traditional, Lee emerged from his cell at 8 a.m. that day and was led to the gallows. A belt was tied around his ankles, a hood put over his head, then the rope placed around his neck. Asked if he had any last words, Lee said calmly, ‘No, drop away.’ Berry duly pulled the lever. Nothing happened. Lee was led away and the mechanism tested again. It worked perfectly. Lee was brought back and the lever was pulled a second time. Again, nothing happened. With both Lee and Berry now frantic, the whole exercise was repeated a third time, only to end without a hanging. The whole execution was temporarily called off. The home secretary, Sir William Harcourt, became involved and soon decided to commute Lee’s sentence to life. He would serve twenty-two years in jail.

Lee was dubbed ‘the man they couldn’t hang’. Yet Lee’s case was not the first. Australian Joseph Samuel, convicted of murdering policeman Joseph Luker in 1803, was hanged near Sydney three times, but on each occasion the rope unravelled or snapped. The country’s governor intervened and also decided that the guilty man should serve life imprisonment instead of being executed a fourth time.

A different kind of escape from the noose occurred in the case of Reginald Woolmington. A jury at the Bristol Assizes had taken just 69 minutes to find the 21-year-old guilty of murder, and he was sentenced to death on 14 February 1935. He had been convicted of killing his 17-year-old estranged wife, Violet, in what appeared to be a crime of passion. Violet had left Woolmington, running away to her mother’s home, but Reginald was desperate to get her back. Reginald went to Violet’s mother’s house in Milborne Port, Somerset, and when Violet refused to return with him she was shot through the heart. Woolmington was quickly arrested, charged and even told police, ‘I done it.’

The farm labourer had admitted that he’d brought a shotgun to the house, but he maintained that he had not intended to shoot Violet and had actually meant to kill himself with it if she could not be persuaded to renew their relationship. The gun, Woolmington said, had gone off by mistake, killing the woman he loved. The judge who condemned him to death had directed the jury that it was the job of Woolmington’s defence to demonstrate that the shooting was accidental. But, after the verdict, an appeal was brought and the case eventually came before the House of Lords. It found that ‘No matter what the charge or where the trial, the principle that the prosecution must prove the guilt of the prisoner is part of the common law of England.’ Woolmington was acquitted in what would become a defining moment in English law regarding the presumption of innocence in cases of murder.

4…

assassins who murdered Thomas Becket

Thomas Becket was not the only person to be savagely murdered in a cathedral. In 1478 Giuliano de’ Medici, co-ruler of Renaissance Florence, was stabbed to death during High Mass inside the city’s duomo as part of a failed conspiracy to overthrow him and his brother. But it is Becket’s death, in Canterbury Cathedral, on the evening of 29 December 1170, that is much better known today. At the time it sent shock waves through medieval Europe, and his murder remains the most notorious of the period.

‘Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest?’ Henry II’s famous frustrated plea came after the king of England had finally lost all patience with Becket, his former friend. Henry had ascended to the throne at just 21, in 1154, and soon appointed Becket as chancellor – effectively his right-hand man – on the advice of the then Archbishop of Canterbury, Theobald. Becket, the son of a London merchant, had been Theobald’s own clerk and shown himself to be highly competent. Henry was initially delighted with the choice. Becket reliably carried out the king’s bidding and the pair spent time carousing and hunting together.

It was only when Henry made a reluctant Becket take up the position of Archbishop of Canterbury, in 1162, that the trouble began. Becket had never been a priest, but once in England’s most senior ecclesiastical post he promptly resigned as chancellor, became increasingly devout and a strident defender of Church power. Rather than helping Henry control the institution as the monarch had hoped, Becket became a thorn in his side. The pair clashed over issues such as the right of clergy to be tried by the Church’s own courts, and Becket incurred the king’s wrath by excommunicating one of his senior barons. When Henry tried to put Becket on trial, the Archbishop fled abroad.

In December 1170, the two factions reached an accommodation, but when Becket returned to England to resume his position he immediately excommunicated three bishops appointed by Henry. The king, in Normandy at the time, was irate. He may not have used the exact words of the much-repeated line above, but contemporary chroniclers recorded that he spoke angrily of being ‘treated with such shameful contempt by a low-born clerk’ and asked why no one had ‘avenged’ him.

Depiction of the Thomas Becket murder. (Courtesy of Wellcome Library, London)

It might not have been meant as a call to action, but four impressionable knights who were present certainly got that idea. William de Tracy, Reginald fitz Urse, Hugh de Morville and Richard le Breton rushed to England determined to teach Becket a lesson. At Canterbury Cathedral they confronted the archbishop, trying to take him prisoner. He refused, saying, ‘I am prepared to die for Christ and for His Church.’

First they tried to drag Becket outside, but he clung to a pillar in the north-west transept of the cathedral. The first to strike him was de Tracy, who gave Becket a glancing blow to the head with his sword. As de Morville held back onlookers, the other three knights rained down more blows on their victim. A final blow by le Breton smote off the top of the archbishop’s head – his brains spilling out as he collapsed on to the stone floor. It was delivered with such force that the weapon shattered into pieces.

The killers fled. When Henry heard what they’d done, he is said to have been filled with remorse, admitting that his ‘incautious words’ might have been to blame. There was widespread shock and anger at Becket’s murder, and he became seen by worshippers all over the continent as a martyr. His tomb in Canterbury was soon a place of pilgrimage. In 1173 Becket was canonised by Pope Alexander III. In such a climate Henry was forced to do public penance at Becket’s tomb by walking to it barefoot in a smock whilst being whipped.

So what of the four actual culprits? For a year they holed up in Knaresborough Castle in Yorkshire. Henry did not have them arrested but neither did he lift a finger to help them. When they were excommunicated by the pope, all four travelled to Rome in a bid to gain forgiveness. The pope exiled them to the Holy Land for fourteen years. No one is sure of their fate after that. Some said they died in Flanders as hermits. There were many other stories, but it’s likely that they died within a few years, while still in the Middle East. Twenty years after Becket’s murder, chronicler Roger Howden claimed to have found their graves in Jerusalem inscribed with the epitaph: ‘Here lie those wretches who martyred Blessed Thomas, Archbishop of Canterbury.’

5…

feet long – the bath that convicted serial killer George Smith

On 9 July 1912, Bessie Mundy bought a 5ft cast-iron bath for £1, 17s, 6d, successfully haggling the price down from £2. Little did she know that, within days, it would become the instrument of her murder.

Bessie’s ‘husband’ was picture restorer Henry Williams. She possessed a large inheritance, and had originally married Henry two years earlier in Weymouth. It wasn’t his real name. He was in fact George Smith, a 40-year-old serial bigamist with a history of conning women into marrying him and then absconding with their cash and belongings. After disappearing for eighteen months with some of her money, Williams resurfaced. The pair reconciled and took up lodgings in Herne Bay, Kent. Smith had discovered that to get his hands on Bessie’s full £2,500 fortune, held in a trust, she would have to make a will in his favour, and this was duly arranged on 8 July.

Over the next few days Smith twice took Bessie, 33, to a doctor. She had complained of headaches, but Smith told Dr Frank French that she had been suffering from ‘fits’. French could find little wrong, prescribing sedatives. Then, on the morning of 13 July, a note from Smith was delivered to French with some dramatic news – his wife was dead, having apparently drowned in the bath while he was out. French rushed over and found Bessie submerged in the new tub, still clutching a bar of soap. He found no evidence of a struggle and put her death down to an epileptic fit. Within a few months Smith inherited all her money. The bath was returned to the ironmonger for a full refund.

By November 1913, Smith had married another woman, 25-year-old nurse Alice Burnham. A month later the couple went on honeymoon to Blackpool where they stayed in a boarding house. Again Smith took her to the doctor with headaches. Three days later, on 12 December, he apparently went upstairs and discovered that his wife had died in the bath. An inquest found that Alice had drowned after fainting. Smith collected £500 in life insurance.

No connection between the two deaths was made until January 1915, when the police were contacted by Alice’s father who, from newspaper reports, had noticed the similarity between his daughter’s death and a third, that of 38-year-old Margaret Lloyd of Highgate, London. She had died in similar circumstances, in her bath, having been found by her husband, John Lloyd, just one day after their marriage on 18 December 1914.

Police intercepted Lloyd at a solicitor’s office where he was due to discuss Margaret’s £700 life insurance policy, and it soon became clear that he and George Smith were one and the same. He was arrested. Further enquiries by Detective Inspector Arthur Neil made the connection with Bessie’s death in Kent.

Renowned pathologist Bernard Spilsbury was called in to help determine how the women had drowned. Spilsbury had established his reputation with the 1910 Dr Crippen case (see page 20). His work had also brought arsenic poisoner Frederick Seddon to justice in 1912. The ‘Brides in the Bath’ case would cement Spilsbury’s fame.

The bodies of all three women were now exhumed. Spilsbury could find no signs of violence or poison. He asked for the bathtubs in which the women had died to be sent up to London for examination. Spilsbury considered whether the women might have died from epileptic fits. He considered the shape and measurements of the baths. Bessie’s was just 5ft long – considerably shorter than her height, at 5ft 7in. The tub tapered at the foot end and at the time of her death it had just 9in of water in it. If she had really died from drowning as a result of an epileptic fit, Spilsbury figured that the stiffening and extension of her legs would have pushed her head up out of the water, not underneath it. However, towards the end of a fit the muscles relax, in which case why had she still been holding the bar of soap when Dr French found her?

Experiments using an experienced female swimmer were conducted and Spilsbury concluded that the only way to have drowned the victims, without signs of a struggle, was to have suddenly pulled them under the surface of the water by the ankles. When this was done with the swimmer in question, water had rushed into her nostrils and mouth. She became unconscious and had to be revived.

At Smith’s trial in June 1915 the bath itself was brought into the courtroom so that Spilsbury could demonstrate his theories. It was enough to convince the jury of the defendant’s guilt and Smith was convicted and hanged that August.

6…

crucial letters in the telegraph that caught a killer

‘Have strong suspicions that Crippen, London cellar murderer and accomplice are among saloon passengers. Moustache taken off, growing beard. Accomplice dressed as a boy. Voice, manner and build undoubtedly a girl.’

This message, sent at 3 p.m. on 22 July 1910, via the new wonder of the Marconi wireless telegraph machine, came from Captain Kendall, skipper of the SS Montrose. He had become convinced that aboard his ship, which was making its way across the Atlantic to Canada, were Dr Hawley Harvey Crippen and his lover, Ethel Le Neve. The couple were wanted for the murder of Crippen’s wife, Cora, who had suddenly vanished that February. Crippen had claimed that his adulterous wife, a musical hall singer, had left him and subsequently died of natural causes in America. But Cora’s friends raised their concerns with police after seeing Le Neve wearing Mrs Crippen’s clothes and jewellery. Police interviewed Dr Crippen and searched his London home but could find nothing. Rashly, Crippen and Le Neve then fled the country, prompting detectives to search the house again. This time, under the basement floor, they found a dismembered human torso, with traces of poison, and put out urgent arrest warrants for the runaway pair, whom they now believed responsible for Cora’s murder. Recognising his fugitive passengers from a newspaper report, Kendall’s prompt alert gave police the chance to board a faster ship across the ocean and intercept Crippen and Le Neve as they arrived in Quebec. Crippen, who maintained his innocence to the end, was convicted of murdering Cora and hanged on 23 November at Pentonville Prison. Le Neve, charged as an accessory, was acquitted.

Crippen’s capture was made possible through the new ‘ship to shore’ telegraph, but this was not the first time similar technology had been used to catch a killer. In fact a pioneering electric telegraph system had proved crucial in a murder case more than half a century earlier.

On 1 January 1845, a Mrs Ashley of Salt Hill, Slough, was alerted by screaming from the adjoining cottage. Going next door, she found her neighbour Sarah Hart lying on the floor, frothing at the mouth. Mrs Ashley had also seen a man in a distinctive Quaker-style coat disappearing down the road. Sarah had been poisoned with prussic acid, added to her glass of beer. She died almost immediately. The alarm was raised and a Reverend Champnes raced to the local station, suspecting that the killer, dressed in the distinctive clothes of a Quaker, would try and make his getaway by rail. Sure enough, Champnes arrived just in time to see the man boarding the 7.42 p.m. train to London. Champnes informed the station master, who seized the opportunity to use the new electric telegraph machine at his disposal. The new equipment, patented by two English scientists in 1837, involved needles that pointed to different letters on a board. Introduced primarily as a means of improving safety on the railway, it would now be used to alert police that a suspected murderer was on the way to the capital. A message was sent stating that the man in question would be arriving on a train to Paddington in the second first-class carriage. However, the machine was unable to transmit the word Q and so the message read that the suspect was in the garb of a ‘KWAKER’. After being asked to repeat the message several times by the London operator, it was eventually understood that these six letters were in fact meant to read ‘Quaker’. Armed with this description, local police successfully identified the suspect, wearing his long brown coat, as he left the train. He was followed and later arrested.

Crippen on trial. (Courtesy of Wellcome Library, London)

He was John Tawell, a man who had already cheated the noose once in 1814 after being found in possession of forged notes from a Quaker-owned bank. The Society of Friends, of which he would become a member, had interceded then to get him the lesser sentence of being transported to Australia, where he had gone on to become a wealthy businessman. Tawell later returned to England with his family. However, he had then begun an affair with Sarah Hart, a nurse, fathering two illegitimate children by her. When Tawell’s wife died, rather than marrying Sarah, he had wed a Quaker widow. Worrying that his secret family might be exposed, Tawell decided to poison his mistress. At Tawell’s trial in Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, his laughable defence was that Sarah had not been poisoned at all but had died after eating too many pips from apples, which contain tiny amounts of cyanide. Tawell was swiftly convicted and hanged.

There seems little doubt that Tawell was guilty and had been brought to justice speedily thanks to advances in science. Ironically, however, new techniques would cast doubt on Crippen’s conviction more than 100 years after he went to the gallows. DNA tests on skin samples presented at the original trial, conducted at Michigan State University in 2007, apparently showed that the body found by police at Crippen’s home was male.

7…

pounds – how much serial killers Burke and Hare were paid for their first body

In the Greyfriars Kirkyard in Edinburgh there are two graves covered in strange ironwork cages, dating back to the early 1800s. Known as mortsafes, these devices were once widespread throughout cemeteries. They afforded some protection against grave robbers aiming to steal bodies of the recently deceased in order to sell them on for dissection in what was, by the start of the nineteenth century, a lucrative business. Body-snatching has been with us for centuries, with physicians keen to get their hands on fresh corpses to identify how human anatomy works but often thwarted by the legal and religious restrictions of their times. In Britain, the Murder Act of 1752 allowed for the remains of hanged killers to be given over for dissection, but with the burgeoning of medical science, there were still simply not enough dead criminals to keep up with the growth in demand from surgeons. By the turn of the century body-snatching had become rife, with many in the medical profession prepared to pay tidy sums for cadavers to so-called ‘resurrectionists’ without asking many questions about their provenance.

Two of the first people to hit upon the idea that murder might provide a better resource of bodies than pilfering them from churchyards were Helen Torrence and Jean Waldie. In the same year as the Murder Act came into force, they went to the gallows in Edinburgh having smothered 9-year-old John Dallas and sold his body to a doctor for 2s. It would take another eighty years before William Burke and William Hare would turn this deadly concept into a fully fledged business.

In November 1827 the Irish-born pair were hard up and living at a boarding house run by Hare’s wife, Margaret, in the city’s West Port. When an elderly lodger called Donald died of natural causes still owing rent, they came up with a plan to make up for the shortfall. Stuffing his real coffin with bark, Burke and Hare put the old soldier’s body into a tea-chest and hauled it round to the back door of Dr Robert Knox, a distinguished anatomy lecturer. He paid them £7 10s for the body – more than they could hope to earn in months.

Burke and Hare. (Courtesy of Wellcome Library, London)

This, thought Burke and Hare, was easy money and, as Edinburgh was then one of the leading centres for the study of anatomy, the demand for corpses was huge. Knox himself sometimes conducted dissections for students twice a day. It was then that the duo had a brainwave about how to get more bodies: by preying on the sort of individuals unlikely to be missed! Thus in early 1928 Burke and Hare targeted their first victim, another lodger at Hare’s wife’s boarding house. They got the man, named Joseph, drunk and smothered him until he expired. This time Knox paid £10 for the body, which would become Burke and Hare’s standard fee as they delivered a string of corpses to the eager anatomist over the next few months. Fifteen more people, drawn from the city’s underclasses, would perish at the hands of Burke and Hare, including prostitutes, a salt pedlar and even a relative of Burke’s partner, Helen McDougal. The usual method of murder was first to ply the victim with alcohol, then sit on their chest while covering their nose and mouth. This technique, henceforth known as ‘burking’, had the added benefit of leaving the bodies virtually pristine, something the anatomists preferred.

There’s no doubt that by the time Burke and Hare killed a well-known local character, ‘Daft’ Jamie Wilson, Knox knew what they were doing – his medical students recognised the corpse – but he turned a blind eye, allowing the killing to continue.

Burke and Hare were finally caught in November 1828, when the corpse of one victim, Margaret Docherty, was found under a bed by two suspicious lodgers. However, while they were alerting the authorities, the victim’s body was spirited away to Knox. With no bodies now in a fit state to prove that Burke and Hare had actually murdered them, the police struggled to put together a case. Eventually Hare ratted on his associate in exchange for his freedom. Burke was convicted and hanged on 28 January 1829. Knox escaped punishment.

The case of Burke and Hare did not appear to put off others trying the same ruse. In 1831 the so-called London Burkers, John Bishop and Thomas Williams, went to the gallows at Newgate after trying to sell the body of a 14-year-old boy they’d killed to surgeons. In the same year Elizabeth Ross was hanged for killing Catherine Walsh and selling her body on.

Ironically, all of them, including Burke, would end up on the dissecting table themselves, as provided for by the law. The following year, legislation was brought in making it easier for anatomists to procure bodies legitimately.

8…

steps at the heart of a Tudor murder mystery

Suicide or murder? It’s sometimes hard to tell. What appears to have been a case of someone taking their own life can later turn out to be a homicide. On the morning of 18 June 1982, the body of a man was found hanging from scaffolding underneath Blackfriars Bridge in London. His clothes were stuffed with bricks and $15,000 in three currencies. Police quickly discovered that the dead man was an Italian, Roberto Calvi, the ex-chairman of the Banco Ambrosiano, an institution that was closely linked to the Vatican and had just gone bust, owing the Mafia millions. An inquest initially ruled that the disgraced 62-year-old had committed suicide, but a year later a new inquest recorded an open verdict in light of the suspicious circumstances. In 2005 five men were prosecuted in Italy for murdering Calvi and were acquitted, though it’s now generally accepted that there were powerful factions at play who had an interest in seeing ‘God’s Banker’ silenced.

In other cases what seems a straightforward unlawful killing can turn out to be a suicide after all. In 1721 Catherine Shaw was found in the Edinburgh flat where she lived, lying in a pool of blood, a knife by her side. A constable had broken in after a neighbour, Mr Morrison, had heard Catherine arguing with her father William about her love life. Morrison swore that he had overheard Catherine say, ‘Cruel father, thou art the cause of my death!’ through the thin partition wall, followed by the sound of Shaw leaving the property. Then, hearing desperate groans, Morrison had rushed to get help. Catherine lived long enough to be asked if she’d been attacked by her father. She appeared to give a slight nod. William’s fate was sealed when he returned with blood on his shirt, which he said was the result of cutting himself shaving. He was, however, found guilty of murder and hanged that November. A few months later the authorities were left red-faced when Catherine’s suicide note turned up – it had slipped down the back of the mantelpiece in the room where she was found dying.

History is littered with other examples of mysterious deaths that may have been tragic suicides or possibly something more sinister. For example, was the artist Van Gogh really stupid enough to shoot himself in the stomach, leading to an agonising twenty-nine-hour death? Did actress Marilyn Monroe take an overdose or was she the victim of a murder and a clever cover-up?

One of the most intriguing such cases was the puzzling death of Amy Robsart, which captivated Elizabethan England. By 1560 Amy was estranged from her husband Robert Dudley, who had become close to Queen Elizabeth I. When her body was found at the bottom of some stairs at her home, Cumnor Place, in Oxfordshire, on 8 September, there were whispers that the 28-year-old had not simply fallen, breaking her neck, as the official inquest concluded. Lord Robert’s steward, Thomas Blount, alluded to suicide when he wrote to his master suggesting that Amy may not have been in her right mind. Others suggested that Amy might have been murdered, with Dudley the chief suspect. The idea was that with his wife out of the way, Dudley would be free to marry the queen.

Dudley, however, seems to have been genuinely shocked when informed of Amy’s death, and if he did hope to advance his cause at court via murder, then he was to be sorely disappointed. The queen was forced to distance herself from Dudley, who was left permanently tainted by the rumours. Both the queen and Dudley seem too shrewd not to have known the likely fallout caused by any association with such a scandalous scheme.

So what happened? If Amy had planned suicide then throwing herself down a flight of stairs that ‘by reporte was but eight steppes’ seems an unusual method to choose. If she did have a death wish, why had she just written to her tailor ordering alterations to a gown? Some have proposed that Amy may have been unwell with breast cancer and that this caused her to fall. But the evidence is scant and, while it is possible to break your neck falling down a few steps, the timing of her death seems rather convenient. There were two wounds on Amy’s head. These were consistent with the accident scenario but also with the notion that she was subjected to violence.

It seems very possible that foul play was involved. Perhaps Amy died on the orders of William Cecil, Elizabeth’s manipulative chief adviser who was vehemently opposed to a union between Dudley and the queen. Alternatively it could have been the work of Dudley’s over-zealous retainer, Sir Richard Verney, or some other unknown figure with their own motive. Some 400 years later we are little closer to knowing the truth.

9…

inches of pipe in the case of Lord Lucan

In past times English peers of the realm could expect to get away with murder, or perhaps receive a lesser conviction for slaying their fellow man. They might, for instance, receive a pardon from the king, especially if they were an ally. From the fourteenth century (until 1948) peers had the right to be tried by fellow members of the House of Lords. But their colleagues in ermine were often reluctant to bring in a guilty verdict for murder, frequently opting for acquittal or an alternative conviction for manslaughter instead.

Some were not so lucky. In 1541, after a man was killed in a late-night poaching prank in Sussex, Lord Dacre was expecting a royal pardon for his part in the affair. Instead, under heavy direction from the irate Henry VIII, his peers found him guilty of murder. Dacre, 26, was hanged at Tyburn, London, like a ‘common criminal’. In April 1760, 40-year-old Earl Ferrers was found guilty by his peers of murdering his steward, John Johnson. An inebriated Ferrers had shot Johnson at his mansion during a business meeting. He also went to the gallows at Tyburn.

While Earl Ferrers was the last member of the House of Lords to be convicted as a murderer, he was not the last to be branded as such by a court. More than two centuries later, an inquest jury concluded that Lord Lucan, 39, was responsible for a much more duplicitous killing. However, thanks to Lucan’s now notorious disappearance, he would never face a criminal trial on the charge. In fact, the controversial episode would itself lead to a change in the law, meaning that inquest juries could no longer name murderers.

By the time of the events of 7 November 1974, Lucan was deeply in debt from gambling and estranged from his wife, Veronica, having fought a fierce custody battle over their children. At 9.50 p.m. Lady Lucan burst into a pub near the family home in No. 46 Lower Belgrave Street, London, crying, ‘I’ve just escaped from being murdered … he’s murdered my nanny.’

In the basement of the house, police found the dead body of the nanny, Sandra Rivett, in a sack. She had been beaten over the head with a blunt instrument. Lady Lucan had been assaulted too, after going to find Sandra, who was supposed to have been making tea. She stated that her attacker was Lucan and that after grappling together they had ended up in a heap, exhausted. He had then admitted to killing Sandra. Lucan had apparently mistaken the 29-year-old in the darkened room for his real target, his wife, who was of a similar build. He knew that Sandra usually had Thursday nights off, but not that on this occasion she had changed the day. A little later Lady Lucan managed to trick her husband and flee out of the house to the pub.

In the hallway, police found a ‘grossly distorted’ 9in section of lead pipe, which had surgical tape attached. On it were found a mixture of Group A blood (Lady Lucan’s type) and Group B blood (Sandra’s). It was quickly judged to be the weapon that had been used to kill Sandra and attack Lady Lucan.