15,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

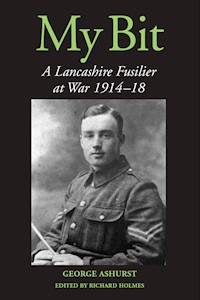

George Ashurst served with the Lancashire Fusiliers, taking part in First Ypres, Gallipoli and the Somme, and enduring months of trench warfare on the Western Front, making numerous grim and dangerous patrols into no man's land. His memoirs vividly reveal the reality of life in the trenches and the feelings of those who had to suffer it. Ashurst was often frightened and uncertain, occasionally infuriated by the 'shirking' amongst the officers, was usually ready for a cigarette or drink, but when his battalion attacked he would not shrink from his duty. My Bit is a fascinating and moving first-hand account of the First World War written by a working-class soldier.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

MY BIT

A Lancashire Fusilier at War 1914–1918

GEORGE ASHURST

Edited by Richard Holmes

CONTENTS

Title Page

INTRODUCTION

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE

1 A Lancashire Lad

2 Going to the Wars

3 Gassed

4 Gallipoli and Egypt

5 The Somme and Blighty

6 Return to France

7 Right Away to Blighty

NOTES

Copyright

INTRODUCTION

It is doubly surprising that George Ashurst has written of his service in the Lancashire Fusiliers during the First World War. In the first place, it is usually officers or middle-class men serving in the ranks – by preference or circumstance – who have left written accounts of their experiences. There are, it is true, several exceptions – most notably the marvellous Frank Richards – but it remains true to say that well observed first-hand accounts by working-class soldiers are relatively rare. And, as the opening chapter so clearly demonstrates, George Ashurst came from a working-class background typical of that of so many of the soldiers who fought in the First World War. Secondly, the odds against Ashurst surviving to write were almost impossibly high. The fortune of war put him in the path of a German gas attack at First Ypres, ashore on Gallipoli, and over the top on the first day of the Somme. Not only did he survive these pitched battles, but he also bore months of trench warfare across the whole length of the British sector of the Western Front, as well as in Gallipoli, and took part in a dozen or more grim and dangerous trench raids and patrols in no-man’s-land. In the process he did indeed earn two ‘Blighty ones’ – but he was lucky not to share the fate of the 13,642 Lancashire Fusiliers who perished during the war.

George Ashurst wrote the bulk of his memoirs (though not the section dealing with his childhood and youth) from diary and memory in the 1920s. This fact has two important consequences. In the first place, Ashurst was often unaware of the accurate details of the events in which he participated. It is temptingly easy for historians to regard the first-hand accounts – written or oral – of survivors as the pure and undiluted truth. Such is rarely the case. Even when events are recalled shortly after they have happened, memory still plays tricks, with snatches of experience being collated in a haphazard order, like clips of film assembled at random from the cutting-room floor. There is a natural tendency for the mind to shut off the most ghastly episodes, and the stress of battle itself interposes a filter between an event and its observer. Lieutenant Geoffrey Malins, who filmed the British attack on Beaumont Hamel on the first day of the Somme, described the process well:

The noise was terrific. It was as if the earth were lifting bodily and crashing against some immovable object. The very heavens seemed to be falling. Thousands of things were happening at the same moment. The mind could not begin to grasp the barest margin of it all.

And there are other problems. Most front-line soldiers in most wars live on a diet of rumour intermixed with partly explained facts. During the First World War an understandable desire to preserve secrecy coupled with a tendency for information not to filter its way right down the chain of command to the non-commissioned ranks meant that private soldiers and NCOs (and, indeed, a good many officers) often had only the haziest idea of the progress of the war outside the narrow frontage of their own battalion – or even their own company. Rumour made up for the shortage of hard facts, and rumour often coalesced to assume the status of truth in the minds of survivors. Ashurst is consequently in error on several points of detail. He believed, for example, that the mine beneath the Hawthorn Redoubt was blown at 7.30 on the morning of 1 July 1916, and that its explosion was the signal for the assault. He also transposes his battalion’s tour of duty in the Nieuport sector in 1917 with its time in the line north of Ypres in the winter of 1917–18. Ashurst could have corrected these facts by checking them against a regimental or official history, but in the process much of the freshness of his account might have disappeared. Moreover, what soldiers believed to be the case is often as interesting as the objective but bald fact which emerges from official records.

This caveat leads naturally on to the second consequence of the way in which Ashurst wrote. The attitudes he describes are essentially those of the working-class Englishman of sixty years ago. Authority was accepted instinctively, even when those wielding it were disliked. Ashurst’s comrades complained frequently – as British soldiers tend to. They muttered when being given a pep talk by their divisional commander on the eve of the Somme, and gave vent to ‘horrible wishes and curses’ when pushed along on the march by ‘the comfortably mounted adjutant’. But they kept going. Ashurst makes no secret of his contempt for shirking amongst the officers, but is always prepared to give credit where it is due: he describes ‘one gallant young officer’ trying to force panic-stricken men to stand and fight at the point of his revolver. He admired bravery wherever he saw it, and the picture of a signaller springing up onto the bank of the sunken road in front of Beaumont Hamel, only to fall back riddled with bullets, remained engraved on his memory.

Ashurst’s comrades were certainly no angels. They drank to excess when the opportunity offered – many were the worse for drink when their battalion left the regimental depot for war. He describes a brothel in Armentières, its tables ‘swimming in cognac and vinblanc’, with a queue on the stairs, where ‘the boys did their best to stand upright’ when the padre arrived to rebuke them. Valuable items with no clearly identifiable owner were ‘liberated’; Ashurst gives one lively description of the sergeants in his company carrying out a successful tomb-robbing raid by night.

Like so many front-line soldiers of the First World War, Ashurst reveals no particular hatred for his enemy. He was glad of the truce of Christmas 1914, and complains bitterly of ‘the comfortably housed and well fed “Heads” in the rear’ who ‘started the war again’. The Germans are ‘Fritz’ and the Turks ‘Johnny Turk’, and there is no evidence of resentment towards either. Far from it: on one occasion, when burying ‘a good-looking lad’, he took care to place a photograph of the dead German’s family next to his heart, and on another he and his comrades refrained from firing on a German who was ‘too brave to die’. Nevertheless, Ashurst’s lack of any feeling of personal antipathy did not prevent him from doing his duty. He got closer to the German front line than most of his comrades on 1 July 1916, and the frequency with which he was selected for patrols bears testimony to his fighting spirit. He was promoted steadily through the non-commissioned ranks, and was completing his training for a commission when the war ended.

Yet it was not lofty motives that kept him in the trenches; indeed, he admits that he might have considered malingering or desertion, but the former was foreign to his nature and the latter would have shocked his family. There were times when he clearly considered that he had ‘done his bit’, and on one occasion he told his company commander so in as many words. He was glad of his ‘Blightly ones’, and accepted the offer of a commission because he agreed with his men that ‘it was a glorious opportunity … while I was away for my instruction the war might finish’. But there was an innate conviction that the allies must win; that ‘sneaking away [from Suvla Bay] like a thief in the night’ was wrong; that to ‘hold on grimly, suffering heavy casualties but losing no ground’ was the right way to behave.

It is in his dealings with non-Europeans that Ashurst’s prejudices are most evident. He watched a group of mutinous Chinese labourers being rounded up, noting that ‘if quiet had not reigned in that compound those Chinks would have been mown down like wheat. Perhaps this treatment looked a little harsh, but drastic treatment was necessary with this wild, uncivilised crowd.’ He similarly makes no secret of his contempt for the ‘dirty, lousy, unshaven’ Greek labourers at Mudros or the ‘grinning native’ who stole his cigarette in Egypt.

In editing George Ashurst’s memoirs I have made only minimal changes in the text, simply removing many of the inverted commas and capitals with which the original is so liberally seeded. Facts stand as Ashurst recalls them, and many French phrases are those of the British infantryman rather than the dictionary. I have used footnotes to throw more light on individuals or events and to indicate those occasions on which Ashurst’s recollection and a more objective view of history differ, and have inserted passages in italics which put the events that Ashurst describes into their proper context. The text has been checked against Major-General J. C. Latter’s excellent HistoryoftheLancashireFusiliers1914–1918 (2 volumes, Aldershot, 1949), and the appropriate volumes of the HistoryoftheGreatWar,BasedonOfficialDocuments. Where the two conflict, as they do over the layout of the 2nd Battalion’s trenches at Mouse Trap Farm in May 1915, I tend to accept the evidence of the former. It is notable, however, that both histories gloss gently over events which Ashurst describes in harsh detail: his account of his company’s precipitate (and, let it be said, by no means surprising) departure from the line at Mouse Trap Farm has little in common with the regimental history’s description of men ‘retiring’. The 1st Battalion’s performance on 1 July 1916 is reconstructed from the battalion’s War Diary (Public Record Office WO95/2300), and from Dr A. J. Peacock’s useful work on ‘The Sunken Road’ in the occasional journal produced by the Western Front Association, GunFire, vol. 1, no. 3. Dr Peacock himself has been most helpful, as has Mr Bob Grundy, who drew my attention to these memoirs in the first place, and has provided the biographical note on George Ashurst.

In short, almost all of what follows is George Ashurst. Often he is frightened and uncertain, sometimes resentful that it is always the same men who are called upon to do the same dangerous jobs, occasionally infuriated by the fact that his discomforts were not shared by all ranks. He is usually ready for a cigarette or a glass of vinblanc, a game of Crown and Anchor and a sing-song. When gas drifts through the position and someone shouts ‘Retire’, he heeds the call without enquiring too closely into its origins. When his battalion attacks, he keeps going although logic and human nature suggest an early halt in a convenient shell-hole. He is proud to command a smart guard on divisional headquarters, happy to accept promotion, but not prepared to receive an unjust rebuke. His is the timeless voice from the ranks.

RICHARD HOLMES Ropley, 1986

Dr Richard Holmes is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of War Studies at the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst, and is also a Lt.-Col. in the Territorial Army. He is the author of numerous books on military history, most notably TheFiringLine (1985) which has been extravagantly praised.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE

I came to know George Ashurst quite by chance in 1983, when I saw a small article about his war service in a local paper. I called to see him and found that he had written, as he says, ‘a war book’ – in fact a finely written manuscript of some fifty-six thousand words.

Reading the book through, I noticed with great interest that he referred to one of the most famous photographs of trench warfare, that of the Lancashire Fusiliers fixing bayonets, just prior to their attack on 1 July 1916 (IWM Q744). George mentioned that it was taken days before and, as he said to me, ‘you could not move in that trench, it was so packed with men on 1 July’. This clarity of memory is not confined to remembering passages that he had written; indeed, he names a man on the left of the photograph as Corporal Holland, an ‘old soldier’. At the close of the war George was at Ripon, Yorkshire, awaiting a commission. There he was kept on doing clerical work so that he could qualify for seven years’ gratuity. Finally demobbed in January 1919, he went back to Wigan and Prescot Street Locomotive Depot. His job had been kept open for him but he was told to take a month’s holiday and have a good time. This he did, spending most of his gratuity – and who can blame him, after what he had been through?

His return to civilian life meant being a fireman for the Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway Company. Odd hours of starting and finishing made for a difficult social life in the early twenties. In spite of this, George courted a girl from Platt Bridge, a few miles out of Wigan. Her name was Elizabeth Emily Joynson (Lizzie). On 7 April 1926 they were married at St James’s Church, Poolstock, Wigan. A worse time to take a wife could not be found, as the General Strike started on 3 May and George was out of work – no strike pay, nothing.

Indeed, when the strike was over many railway men were told not to return to work until called for. Men were told to report for work in order of seniority and some of the younger railwaymen never got back to work at all. George started work again after eight weeks, a poor start to his married life. One year later, on 2 April 1927, their first child was born, Gladys Audrey. Later a tragedy struck them when a son, Geoffrey, was born, only to die when twelve days old.

Eventually, through a complicated railway procedure, he became a ‘booked driver’ – that is, he would only drive the locomotive and not be called upon to do fireman’s duties. This job he retained until 1960, when he retired, being sixty-five years of age. He described life as a railwayman in a privately printed book, IwanttobeanEngineDriver, by GASH, in the pseudonym of Bob Ashwood. One of George’s pastimes is poetry and verse:

There she goes, so graceful, so fast.

A beautiful sight, as she hurtles past.

Near a hundred tons of shining steel

How weak and dwarfed she makes you feel.

Her powerful body, sleek, streamlined,

A machine created of man’s mind.

Great long limbs, so lithe, so free,

A giant athlete she appears to be.

With strength of a thousand men,

Yet not the soul of one of them.

Not possessing an ounce of brain

Hauls five hundred tons of train.

Hungry monster with unquenchable thirst,

Devouring the miles, drinking to burst.

Running smoothly at terrific speed,

Faster than the Derby’s winning steed.

Over junctions maze of shiny rail,

Charges like maddened harpooned whale.

Snorting out fire and white-hot breath,

Mimics the ancient dragon’s death.

Speeding past yellow fields of corn,

Through wind and fog and wildest storm.

By lonely farm and cottage red,

Through town and city forges ahead.

Up barren hill, down leafy dale,

Her stamina sustains, does not fail.

On blackest night, or hottest day,

Her race is run on permanent way.

Acting quickly to her driver’s will,

Paying tribute to engineer’s skill.

This mighty engine driven by steam,

The fulfilment of James Watt’s dream.

A wonderful descendant in metal,

Of her humble ancestor, ‘The Kettle’.

In the early part of the Second World War George was asked to form, from the railway depot, a Home Guard unit, without uniforms, equipment or weapons – a body of about 50 men. Young and old would parade on Sunday morning for drill and PT under ex-Sergeant Ashurst. Eventually uniforms were forthcoming and rifles – wooden ones. Training was carried out at Central Park, the home of Wigan Rugby Club. At this period weapons were in short supply but one rifle and 20 rounds found their way to George’s unit for shooting practice. This was done on an old colliery tip, regulations being much more relaxed then than now.

After his official retirement George had a part-time job collecting for an Insurance Company. Without a car, this meant ‘footslogging’ to every customer – not that that was alien to him. After that, his last part-time job was at a local abattoir, working in the office. When the firm sold out, he also decided to finish as well, now being eighty years old – a fine working record.

It is surprising that after all the privations of that ghastly war and a hard life on a locomotive footplate George, in his ninety-second year, is in good health, despite suffering a heart attack at Christmas 1985. Whilst I have known him for a relatively short time he has become a pal. I can talk to him on nearly every subject and he has definite views on world matters. To me, George will never be an old man; he will always be a gentleman.

R. B. GRUNDY June 1986

Publisher’sNote

Werecordthat,sadly,GeorgeAshurstdiedon5July1988aged93,andhiswifeLizziediedon19August1991aged87.

1

A Lancashire Lad

I was born on 3 March 1895 in the village of Tontine, a pleasant little place between Manchester and Liverpool. There were about twenty cottages, a beer house and a little Methodist church in the village. When I came into this world my parents already had three children, two girls and one boy.

We lived in an old two-bedroomed house in the middle of a row of houses. We had no modern amenities such as gas, electricity, bathroom, or flush toilet. The kitchen had a stone floor which was mopped and sanded – no oilcloth, carpets, or rugs – and at night the house was lit with paraffin lamps. The furniture consisted of a heavy wooden table, a set of drawers, and three or four heavy wooden chairs. In the back kitchen, fastened to the wall, there were shelves on which the plates and cups and saucers rested when not in use, and two or three hooks were driven into the wall to hold pots and pans, etc. Of course there was no fancy paper on the walls, just a few coats of whiting.

In the kitchen there was a huge iron grate with a hob on one side that held the big iron kettle, and a boiler on the other side of the fire, which burned wood or coal. The grate was black and polished with blacklead, and hot water was always to be had from the boiler. On bath night for the children a zinc bath was brought into the kitchen from the outside, where it hung on a nail driven into the wall. It was partly filled with hot water in which the children sat very uncomfortably to bath.

At the back of the house there was a small garden, big enough to grow a few potatoes, lettuce, cabbages and rhubarb.

We were a poor family. My father worked at a stone quarry about a mile from the village, and his wages were rather poor. To make things worse, he kept half of his wages for himself and spent them at the village pub.

My mother took in other people’s washing to help pay the family budget, and was beaten every Saturday night by my drunken father for her trouble. She baked all our bread, kneading the flour and yeast in a huge ‘pan mug’, then placing it near the fire covered with a towel for the dough to rise. She baked the loaves of bread in tins, but specially for my father she had to bake ‘cobs’ on the oven bottom shelf. Of course during the week she would bake custard pies, apple pies and currant cakes, besides huge ‘barm cakes’ which the children loved, covered in black treacle or golden syrup, and oatmeal for breakfast covered in sugar or treacle. We used to beg for the top cut off father’s boiled egg.

Through my mother’s untiring efforts we were never short of food or clothing. As a young woman she had worked for years at a clothing factory and could always fix us up with cast-offs given to her by neighbours. Of course we didn’t have any pyjamas and slept in our little shirts on old iron beds on which were straw mattresses covered with cheap blankets and any old coats that were available to keep us warm in winter. As soon as I could walk about I had to wear a pair of clogs, but I had a pair of child’s slippers to wear on a Sunday to go to chapel with my elder brother and sisters.

Of course I don’t remember much of my baby days, but something that stands out in my memory quite plainly is what happened on Saturday nights when I stood with my brother and sisters in our shirts on top of the stairs, crying and listening to my drunken father beating my poor mother black and blue, and there was nothing we could do about it.

As I got older it came time for me to go to school. My brother and sisters took me on the first day to a very old school about a mile from home, called Hallgates School. I didn’t mind going to school at all except in the winter time, when it was foggy, snowing and cold. There were no school buses in those days, one slipped and trudged through the sludge.

It came my turn as I got older to take my father’s fresh-cooked breakfast to the quarry before I went to school, and also the breakfast of the man who lived next door. His wife was a very nice lady and always gave me a thick slice of bread which had been dipped in the bacon fat at the bottom of the Dutch oven in which she had cooked her husband’s eggs and bacon – a tasty bit I thoroughly enjoyed as I trotted off to the quarry.

Each Sunday morning I had to make a trip to the parish church of Upholland, not very far from the village, where I had to see the verger in the vestry and get two loaves of bread from him to take to a very old couple in my village.

Everyone in our little village knew every other person in the village, and I would say each other’s business too. Every door was always open to a neighbour, and if anyone required help it was quickly and generously given. The little pub with its cheap, good beer and its domino table was the main recreation and entertainment for most of the men, while the women and children enjoyed their evenings at the little Methodist chapel.

Of course there was no radio, television or cinema, and almost no newspapers. Very often on the winter nights neighbours got together in one house, gossiping, having a sing-song, or playing parlour games. They weren’t troubled about ruining posh furniture and carpets; there were none to spoil. They sat around on anything anywhere, eating sandwiches and drinking tea until it was time to retire to their own homes.

The country around the village in the summer time was beautiful and unspoiled by either people or machines. One could indulge in a long walk through the glorious fields, the silence broken only by the song of the birds or the gentle breeze through the magnificent trees. During school holidays I, along with other village boys, would set off early in the morning with a big bag of bread and jam sandwiches and a bottle of water – or, if lucky, a bottle of home made ginger beer made from nettles, dandelion, burdock, and meadowsweet. The whole day we would wander over the fields and into the woods, jumping ditches, climbing trees, chasing hares and pheasants, and bird-nesting, as happy and carefree as the day was long, trotting home at night tired out and as hungry as a pack of wolves. Then to bed, to sleep the sleep of an untroubled mind and a worn out body.

My father was a drunkard. He never went to church and was not concerned at all about religion. He never hit any of his children; my mother had to do the smacking when any of us was naughty. Still, he never objected to my mother and the children going to church so my mother saw to it that we learned about the Bible and Jesus Christ, and made us go to church twice on Sundays. Practically all our entertainment emanated from the little Methodist chapel, the children thoroughly enjoying the concerts and parties, especially at harvest time, when there was plenty of fruit on show, and at Christmas, when we received little presents and pretty cards.

In those days there was no flying off to the Continent or even going by train for a week at the seaside. In fact I only remember one occasion when I visited the seaside. The children were packed on to a wagonette drawn by one horse. It was a beautiful summer’s day, and we all carried huge packets of sandwiches, fruit and cakes, along with sweets and pop – our destination the sandhills at Southport. We laughed and sang as the old horse trotted along.

At one place on the journey the road went over an old bridge across the canal. We all had to get down off the wagonette to help the horse pull it up the steep gradient. On arrival at Southport it was our first sight of the sea, and we played about on the sands until we were exhausted. It was a glorious time and we all thoroughly enjoyed ourselves. Getting back on the wagonette for the return journey we were so happy, but very tired, and it was a long ride back. We sang the songs we had learned at the little chapel until the rhythmic clop-clop of the old horse’s shoes on the road lulled most of us to sleep long before we reached home.

On odd weekends my father would take me with him on a fishing trip to Abbey Lakes, a private estate not far from our village. To be allowed to get in the estate and fish my father had to pay twopence at the lodge gate. The grounds were beautiful with flowers and trees, and the lake in which we fished was thick with water lilies. In the middle of it was a pretty little island where lovely white swans nested, so that we had to be very careful with our fishing lines as they majestically swam by. There were no really big fish in the lake but we caught a few roach and perch. After a couple of hours we packed up our fishing gear and left the lovely estate, making our way home to dinner, which consisted of some chips and a fried perch.

Another incident that stuck in my childish memory was the day my grandma and grandad came to our house from Pimbo Lane, a village a couple of miles away from Tontine. My grandad was six feet tall; he had grey hair and a bushy grey moustache. He was wearing a black billy cap (bowler hat) tipped a little to one side on his head, a black suit, and a heavy silver chain hanging from his waistcoat pocket, in which he kept his watch. He was a real gentleman to me and he spoke in a soft, posh voice that I loved to hear, not at all like an ordinary railway platelayer which he was. My grandma wore a little close-fitting black bonnet with the ribbons tied under her chin and a black cape round her shoulders edged with lace.

My grandad was carrying a long, heavy wooden box. He opened it to show my mother and father, and I got a peep too. In the box was a man’s long leg. It was my uncle Jack’s leg and they were taking it to the churchyard to bury it. My uncle Jack worked at a brickworks in the village of Pimbo Lane; it was his job to work with the locomotives, taking loaded wagons of bricks to the railway sidings across the village lane. The engine always pushed the wagons in front of it and uncle Jack had to ride on the first wagon.

One day, as the train approached the village lane, uncle Jack noticed children playing on the line. He could not signal to the driver to stop because the train was on a curve and he was out of sight, so uncle Jack quickly jumped down from the wagon and ran as fast as he could to the children, throwing them clear of the path of the wagons. Bravely he had saved the children, but unfortunately one of his legs was caught by the wagon wheels and had to be amputated.

The quarry where my father worked closed down and he was out of work. Whatever my father was he was not lazy, and very soon he got a job down a coal mine. But it was too far away to travel to work each day so we had to move from the village. We got a cottage nearer to his work at a place called Bryn, a mile or so from Ashton-in-Makerfield, quite a fair-sized little town. The new house was much bigger than the cottage we had left, and it had gas light in it with the mantles on.

I and my brother and sisters had to go to a fresh school and church not very far from home. To me there seemed a lot more people, and life was a lot busier at Bryn. The electric trolly trams ran through Bryn on to Ashton-in-Makerfield from Wigan. The lads used to jump on the back step of the trams, gripping the handrail and having a ride while the conductor was collecting the fares inside.

Opposite our house, in the fields, was a farm where I spent a lot of my spare time. In the farmyard there was a huge boiler in which potatoes, cabbages and turnips were boiled, and I would keep the boiler stoked up until all the vegetables were nicely cooked. Then with a bucket I would feed the pigs, sometimes eating a potato myself because it was all very good food. Very often I would return home with a bag of potatoes, vegetables and eggs the farmer gave me for my help.

Every Friday night the children were allowed to stay up a little later than usual because on that night Chippy Bill, in his white apron and ringing his bell, would drive into the lane with his horse-drawn mobile chip cart. There was no chip shop in the lane and everybody seemed to wait for Chippy Bill. Of course we could make chips of our own, but there was something special about Chippy Bill’s. We would hang around the cart watching him put potatoes under his chipper to drop in a tin as chips; then he would bend down and, opening the firehole door under his boiler, he would grab his little shovel and put a few nuts of coal on to the fire, the flames sometimes rising out from the top of the chimney peeping out above the roof of his cart.

We didn’t have a long stay at Bryn. We were just about getting used to the place and everybody. My elder brother got married and left us and my sisters started work in a cotton mill at Wigan, having to travel by train and get up very early in the morning. Anyhow, once again a change of environment was on the cards.

My father got out of the mine and started to work at an iron foundry in Wigan. He also succeeded in getting a brand-new terraced house in Wigan, quite near the famous Wigan Pier. The house had a small front garden and a big back yard. It was fitted with gas lights in every room and we had an outside flush toilet. Of course once again it meant going to a fresh school and church, and our family had grown: there was Mother and Dad and six children, two of them working, so we were not quite so badly off now.

For myself, I found the town boys rather different from the country boys: they were more forward and lacked discipline and respect. I saw that it was far easier to get into serious trouble, especially with the police. Petty thieving was a regular pastime, and if one did not take part and concur with the gang one’s life was made miserably lonely. Distracting a shopkeeper’s attention while another of the gang helped himself was an easy game.

Nearby, the main road ran across a bridge over the canal. The gradient was rather steep and the horse-drawn vehicles going over it with a heavy load could only do it at a walking pace. Brewery lorries were a special and easy target for the boys. While the driver concentrated on his horses one of the boys would climb up the back of the lorry, reach over the backboard and hand down bottle after bottle to the fellows running behind. Then we would scamper off in the darkness and enjoy the spoils.

Once an ice-cream vendor left his handcart in front of a pub while he went in for a drink. While one of the lads kept a look-out the others emptied the biscuit tin into their pockets and then filled the tin with ice cream from the tub, quickly vanishing into the fields to devour it.