25,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Garnet Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

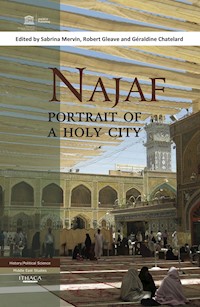

Najaf: Portrait of a Holy City examines the historical and social aspects of one of Iraq's most important cities, a centre of religious learning and devotion for the Shi'i community since medieval times. Through original contributions by leading Iraqi and international scholars, this volume presents several key aspects of the history and development of the city, its global spiritual and educational prominence and its modern role as an economic and political centre. The thirteen essays in this book cover topics such as Najaf's architecture and urban design, as well as the preservation of its built environment; the impact of social movements and revolutions on the city; pilgrimage and religious authority in Najaf; and the city's libraries and intellectual development.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

Najaf

Portrait of a Holy City

Edited by Sabrina Mervin, Robert Gleave and Géraldine Chatelard

Najaf

Portrait of a Holy City

Published by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France, and Ithaca Press, 8 Southern Court, South Street, Reading RG1 4QS, United Kingdom.

© UNESCO 2017

UNESCO ISBN: 9789231001222

ISBN: 9780863725760

This publication is available in Open Access under the Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO (CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo/). By using the content of this publication, the users accept to be bound by the terms of use of the UNESCO Open Access Repository (www.unesco.org/open-access/terms-use-ccbyncsa-en).

The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.

The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors; they are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization.

This book was published with the support of the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Iraq.

First Edition

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Typeset by Samantha Barden

Jacket design by Garnet Publishing

Cover image Géraldine Chatelard

Printed and bound in Lebanon by International Press: [email protected]

Foreword

This collection of essays, made possible thanks to a partnership between the Iraqi Ministry of Culture and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), aims to provide a forum for the presentation of current scholarship on the city of Najaf and its contribution to the history of the Middle East region.

Najaf owes its importance to the presence of the shrine of Imam ‘Ali and the religious, intellectual, economic and political activities that have grown around it. In this volume, the significance of Najaf is explored from various disciplinary viewpoints ranging from archaeology to anthropology, semiology and different historical approaches. New readings are provided of key events in the city’s classical and modern history, and new conceptualisations proposed of Najaf’s role as a centre of faith, learning, economy and authority.

The contributors draw on different educational traditions and philosophies of history, and it is rare that scholars of such different backgrounds come into contact and have their work presented together. UNESCO’s intention in doing so is to make Iraqi scholarship available to those unfamiliar with its achievements, and to bring scholarship on Najaf from outside into Iraqi and Arab intellectual spaces. In this regard, the volume at hand complements UNESCO’s long-standing publication project of General and Regional Histories, which includes significant contributions by local historians offering perspectives on the evolution of societies, the flourishing of cultures, major currents of exchange and interaction with other parts of the world.

In order to break through the barriers of language and culture and bring two scholarly traditions into dialogue with one another, this volume is published in parallel in English and Arabic, and both language editions are made available through Open Access. UNESCO is keen to promote such a policy for the benefit of global knowledge flow, universal access to information and respect for cultural and linguistic diversity.

Axel Plathe

Director of the UNESCO Office for Iraq and UNESCO representative in Iraq (1 February 2014–31 December 2015)

Acknowledgements

The editors would like to thank the Iraqi Ministry of Culture and the UNESCO Office for Iraq for giving them the opportunity to work on this volume. Special mention is due to ‘Aqil al-Mindalawi, ‘Abdallah Sarhid, Rashid Jabbar, Mahdi Salih Latif and Dina al-Dabbagh. Thanks are also extended to Mitchell Albert and Cristina Puerta, who managed the editorial process on behalf of Ithaca Press and the UNESCO Publishing Department, respectively.

This book benefited greatly from the support provided by Salah Mahdi al-Fartusi in Najaf, Hala Fattah in reviewing the contributions and the tireless help of Nassir Ahmad Salih and Robin Beaumont with the bibliography. Finally, the editors are grateful to all those who were instrumental in identifying translators – particularly Orit Bashkin, Aiman H. Haddad, Hassan Nadhem, Caecilia Pieri, Seteney Shami, Nabil al-Tikriti and Keith Watenpaugh.

A Note on Transliteration

The rendering of Arabic and Persian names and terms poses a stylistic challenge when editing a collection of essays by scholars of the Middle East from diverse backgrounds. Overall, our guiding principle has been to ensure consistency across the preferred styles of the thirteen contributors to this volume, with some key exceptions. (For example, although ‘Husayn’ has been adopted here throughout, Iraq’s former dictator is referred to using the most widely conventional spelling, i.e. ‘Saddam Hussein’.)

Moreover, because so little has been published in English on Najaf from a range of critical perspectives, the use of diacritics (but for the Arabic ayn and hamza) has been eschewed in favour of making this book as accessible as possible to the broadest range of readers beyond academic institutions.

Introduction

Making a city the focus of scholarship is not unlike focusing on a person. The Iraqi and international scholars who have come together to discuss Najaf in this book speak of a city having a personality or character. It has moods; it can be lively or moribund; indeed, it can have soul. A city’s personality can inspire loyalty or loathing. A city can be soulful or soulless, lacking character or possessing it amply. It is more than a collection of parts: its people, architecture, institutions, geographical location and history coalesce to form a recognisable whole that is greater than these parts.

Assigning such attributes to a city is, of course, an anthropomorphic trick, a literary conceit – but it is affective, and is particularly apt for Najaf. Najafis are, in the main, fierce promoters of their city’s contribution to the history of the Middle East, one they feel has often been cast aside in favour of the larger metropolitan centre of Baghdad or, because of its supposed greater geostrategic importance, Basra. Najaf owes its own significance not so much to trade or geography, but to its status as the location of the shrine of Imam ‘Ali – who is revered by Shi‘is as Islam’s first authentic caliph – and the ‘religious industry’ that has grown around that site. It is therefore unsurprising that the shrine and the institutions associated with it form the principal focus of the studies in this collection. The city’s honorary title is ‘al-Najaf al-Ashraf’ (‘the Most Illustrious Najaf’), a superlative that asserts a claim for its pre-eminence amongst the Shi‘i shrine cities. As Imam ‘Ali was the First Imam, his burial plot becomes the first location with distinctively Shi‘i memories and character; the manner of his martyrdom and the historical significance attached to that event in the Shi‘i tradition provided Najaf with a series of advantages in its bid for pre-eminence.

This is not to say there were no rivals to challenge Najaf. However, the shrines of various Shi‘i Imams in Madinah were unable to develop beyond being the objects of pilgrimage, located as they were in an atmosphere of Sunni dominance. Other shrines in Iraq and Iran had potential for superseding Najaf in status, and at different times had some success: Karbala (famous for the shrine of Imam Husayn) and Mashhad (home to the tomb of the Eighth Imam, ‘Ali ibn Musa al-Ridha), in particular, developed as major centres of both pilgrimage and learning. Najaf itself experienced periods of both liveliness and quietude, yet the constancy of its centrality to the Shi‘i experience provided for it both an imagined and, quite often, a real position of religious supremacy.

The essays in this collection aim to supply a context for the significance of Najaf. Our objective in bringing together these studies was to provide a forum for the presentation of current scholarship on the city, actively involving scholars from within the Najafi intellectual world as well as those from elsewhere. The contributors draw on different educational traditions, and the themes and disciplinary foci of the various essays here reflect the priorities of those different contexts. It is rare that scholars from different backgrounds come into contact and have their work presented together as part of a single project. Part of our intention in doing so was to make Iraqi scholarship available to those unfamiliar with its achievements, and to bring scholarship on Najaf from outside into Najafi intellectual space. The challenges in this endeavour were not merely academic but also organisational, logistical and managerial. Moreover, the project to assemble a collection of critical scholarly articles about the city of Najaf required explanation and a level of discipline. A panegyric would be a simpler book to write – but a series of critical studies was more demanding for all concerned.

Western scholarship that focuses on Najaf is not plentiful; collecting scholarly production about Najaf from within the Shi‘i tradition, on the other hand, results in a virtual library of its own. This underscores the imbalance between the two traditions, and the not-unjustified complaint that Najaf and its scholarship have rarely been the focus of proper international scholarly attention. Much Western scholarship on Najaf has concentrated not so much on the shrine and its life, but rather on the hawza (the famous clerical college), its scholarly production and the political and societal roles that that it may have played in the history of the region. Apart from a few articles (such as Jacques Berque, ‘Hier à Nagaf et Karbala’, published in 1962) there has been no extended study in a Western language that places the city as the primary topic of investigation. This work, in its English and Arabic editions, aims to contribute towards filling this gap – although we recognise that the eclectic nature of a collection of scholars will not, in itself, produce a critical history of Najaf and its significance.

It is worth reflecting on which scholarship in Arabic has broken through the barriers of language and culture to provide useful secondary-source material on Najaf for Western scholars. The difference between primary and secondary literature has been central to Western approaches to scholarship. Primary sources come from inside the tradition, and are so deeply involved in the mode of scholarship internal to the tradition that they offer limited utility for a critical scholar – that is, beyond being a reflection of the worldview of those subjects one is studying. For secondary scholarship, the assumption is of a critical edge and scholarly attitude that more accurately accord with the tradition of scholarly investigation in Western Europe and North America. The classification into ‘primary’ and ‘secondary’ is somewhat arbitrary, and can be criticised as imposing a particular version of scholarly activity on the sources one is studying. The regular failure of scholars writing in Western languages to refer to Arabic scholarship on Najaf signals the need for volumes such as this one; Najaf: Portrait of a Holy City brings the secondary scholarship of the two traditions into dialogue with one another. Occasionally, what is properly a scholarly analysis is treated as so entrenched in the values of the subject of study that it is better seen as a primary rather than a secondary source.

Needless to say, the distinction between the two categories is sometimes coloured by value-laden judgements. The source most consulted is, of course, the compendious collection Mawsu‘at al-Najaf al-ashraf (Encyclopaedia ofNoble Najaf) of Ja‘far al-Dujayli, a twenty-two-volume work published between 1993 and 2003 by this Najafi intellectual. Assisted by a team of advisors on this project, al-Dujayli produced an essential reference work to which nearly all commentators on the affairs of Najaf refer. Similarly, the sixth volume of Mawsu‘at al-‘atabat al-muqadassa (Encyclopaedia of the Holy Shrines) by the Najafi literary figure Ja‘far al-Khalili (d. 1985) is much used. Standalone histories of the city have also proven useful, none more so than Dalil al-Najafal-ashraf (Guide to NobleNajaf) by ‘Abd al-Hadi al-Fadli, along with the extensive, memoir-type work Fusul min tarikh al-Najaf wabuhuth ukhra (Chapters in the History of Najaf and OtherEssays) by ʻAbd al-Rahim Muhammad ʻAli, edited by Kamil Salman al-Juburi. Al-Juburi’s polymathic output also includes works on life and customs in Najaf, and has been much used by historians of Najaf in the early twentieth century. His enormous al-Najaf al-ashraf wa al-thawraal-ʻiraqiyya al-kubra 1920 (Noble Najaf and the GreatIraqi Revolt of 1920) is beginning to be used as a major source by historians based in the West, as an essential source text for the 1920 revolution. In terms of studies of the hawza institutions, ‘Ali al-Bahadili’s al-Hawza al-‘ilmiyya fi al-Najaf (The Religious Seminaryof Najaf) remains the most-consulted reference for its twentieth-century history, with Muhammad al-Gharawi’s al-Hawza al-ʻilmiyya fi al-Najaf al-ashraf (The Religious Seminary ofNoble Najaf) also regularly referred to, as well as ‘Abd al-Hadi al-Hakim’s Hawzat al-Najaf al-ashraf, al-nizamwa mashari‘ al-islah (The Seminaries of Noble Najaf: Organisationand Reform). Arabic biographical dictionaries of well-known Najaf residents, such as Mu‘jam rijal al-fikr wa-al-adabfi al-Najaf (Dictionary of Thinkers and Men of Lettersof Najaf) by Muhammad Hadi al-Amini, are occasionally used as secondary rather than primary sources; for biographies of more contemporary scholars, the second volume of al-Gharawi’s Ma‘a ‘ulama al-Najaf al-ashraf (With the Clerics ofNoble Najaf) is also used.

These works are the principal points of reference for scholars working on Najaf in Western languages. They are not numerous, and normally an account of Najaf’s significance is nestled within a broader account of the political history of southern Iraq or the history of the Shi‘is in the region.

Chibli Mallat’s TheRenewal of Islamic Law: Muhammad Baqer as-Sadr, Najafandthe Shi‘i International (Cambridge University Press, 2003) advertises itself as making Najaf its prime focus, and certainly some of the changes that occurred in Najaf’s intellectual life in the 1960s and 1970s are explored in this work. However, his main area of interest is, as the title suggests, the work and thoughts of Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr (d. 1980), the influential Iraqi Shi‘i cleric, philosopher and founder of the Islamic Da‘wa Party, as expressed in al-Sadr’s discipline-defining Iqtisaduna (Our Economy). Najaf figures as the location of al-Sadr’s activities rather than as a locale worthy of attention in itself. Mallat’s examination of Najaf can best be described as incomplete, and follows the general focus of works compiled before the First Gulf War of 1991 – before Iraqi Shi‘is emerged as a topic meriting study. The renowned Palestinian-born historian of Iraq, Hanna Batatu, refers to Najaf in his hugely influential study of the history of Iraqi communist (and other revolutionary) movements, The Old Social Classes and the Revolutionary Movements ofIraq (Princeton University Press, 1979); yet this work provides little background for Najaf’s stature as a centre of religious authority, instead focusing on the extent to which dynamics within the city owed more to tribal divisions. This general trend of neglecting the religious dimension can also be seen in the work of Abbas Kelidar (The Integration of Modern Iraq [New York: St Martin’s Press, 1979]) and Marion Farouk-Sluglett and Peter Sluglett (Iraq since 1958: From Revolution toDictatorship [London: KPI Ltd, 1987]).

The 1991 Shi‘i uprisings in Najaf and other cities in southern Iraq had an important impact on the study of Iraqi Shi‘ism. Before these events, such academic pursuits were the preserve a very small number of researchers in Western Europe and North America. After 1991, every publication on Iraqi Shi‘is and Iraq garnered a high level of attention, and provided the springboard for a series of detailed studies published in the 1990s and afterward. Those that made the most important contributions to the understanding of Najaf were, inevitably, focused on the interface between its religious culture and political activity. Pierre-Jean Luizard’s La formation de l’Irak contemporain, published in 1991 (Paris: CNRS Éditions), soon became a reference point for scholarship on the ‘ulama (the Shi‘i clerical establishment) and the Iraqi Shi‘is in the early twentieth century; this book also describes the rebellion of 1917–18 in Najaf as the city’s defining moment. Exploiting a wide range of historians writing in Arabic and treating their work as serious secondary contributions, Luizard places Najaf as the central hub – the city and its political and intellectual activity connecting, to an extent, the various revolts and rebellions of subsequent tumultuous years.

Yitzhak Nakash’s The Shi‘is of Iraq, published in 1994 (Princeton University Press), similarly engages with Arab (and Arabic-language) scholarship, and became the first port of call for many embarking on the study of Iraqi Shi‘ism. Nakash’s focus on the ‘ulama and its cooperation with the tribal dynamics of the Iraqi Shi‘i community led to a recognition of Najaf as a crucial space in which these different societal structures (and pressures) were worked through. However, Meir Litvak’s Shiʻi Scholars of Nineteenth-Century Iraq: theʻUlama of Najaf and Karbala, published in 1998 (Cambridge University Press), probably had the greatest impact upon the study of Najaf as a centre of religious and intellectual life in southern Iraq, and as the centre for an international network of Shi‘i scholars and communities. Litvak’s work provided a detailed historical analysis (in English for the first time) of the establishment and maintenance of Najaf as an international Shi‘i node. In doing so, he made extensive use of primary and secondary literature, including the works of al-Fadli, al-Bahadili and al-Khalili.

The second Gulf conflict in 2003, and the ensuing sectarian violence in Iraq, led to an outburst of Western scholarship on the Shi‘is of Iraq, primarily in English. The use of Arabic-language scholarship within this growing academic production was enhanced not only by the wider availability of sources, but also by the introduction of Arabic-speaking scholars into the field. With regard to the study of Najaf as a centre of Shi‘i devotion and as a political arena, one must consider the work of Ferhad Ibrahim (Konfessionalismus und Politik in der arabischen Welt: Die Schiiten im Irak [Münster: LIT Verlag]), Faleh Abdul-Jabar (The Shi‘ite Movement in Iraq [London: Saqi, 2003]) and, more recently, ‘Abbas Kadhem (Reclaiming Iraq: The 1920 Revolution and the Founding of the Modern State [Austin University of Texas Press]), as well as Writing The Modern History of Iraq: Historiographical and Political Challenges (Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Company, 2012), a collection of essays edited by Jordi Tejel, Peter Sluglett, Riccardo Bocco and Hamit Bozarslan. These works have all made the findings of Iraqi scholars more widely available to a cadre of Western historians and political scientists who have not (yet) fully appreciated the potential contribution of Arabic-language secondary scholarship to the study of Shi‘ism generally, and the significance of Najaf in particular.

It is with this background in mind that, as noted, this collection of essays aims to bring the different traditions of scholarship together. Our goal is to embark upon a tentative exploration of the significance and importance of Najaf from various disciplinary viewpoints, ranging from archaeology to anthropology and different historical approaches. The city itself, as mentioned, has both a symbolic role within the international Shi‘i community and a historical role within the development of Iraq and the region. These two aspects of Najaf’s identity need to be borne in mind when reading the contributions included in each of the three sections of this volume.

I – Najaf: A Sacred City

The collection begins with a series of essays on Najaf’s aspect as a holy site. Sacred cities require a foundational story, a vibrant present and the promise of durable future. The mainsprings of Najaf lie in its interrelationship with the nearby locations of Hira and Kufa – both of which predate Najaf, but provide the historical foundations (literally as well as metaphorically) for the city’s subsequent establishment and growth. Alastair Northedge explores precisely this interrelationship in ‘The Foundation of Three Cities: Hira, Kufa and Najaf’. Here Najaf appears as a sort of sacred palimpsest, overwriting the great civilisations of the past, but also acting as the culmination and fulfilment of those civilisations. That, at least, is how it is imagined. Northedge combines the ‘facts’ of archaeology with the constructed historical record to provide Najaf with a prehistory that links it with former glories.

The foundation story of Najaf, the burial there of Imam ‘Ali and the subsequent construction of his shrine is, of course, central to the city’s narrative. Uncovering that story forms a central theme in Salah Mahdi al-Fartusi’s essay, ‘The History and Architecture of the Imam ‘Ali Shrine’. Al-Fartusi takes a more narrative approach to the history of the shrine complex. He has completed, of course, a major study of the shrine and its architecture (in his Marqad wa-darih amir al-mu’minin [The Tomb and Mausoleum of the Commander ofthe Faithful] of 2010), and here we have insight into his extensive research. The accounts of the shrine and its construction in various historical works are collated and presented here for analysis, to see how they inform (or possibly misinform) our account of the building itself as it currently stands. The historical sources, such as they are, do record a grave, a tomb (sanduq) and a series of overlying buildings from different eras, until the Safavid period. The Persian Shi‘i Safavids, particularly Shah ‘Abbas I, were responsible for much of the present impressive structure, with the dome gilt provided by the post-Safavid ruler Nadir Shah.

The shrine attracts scholars and pilgrims alike, but the burial site’s other major contribution is the industry surrounding the enormous cemetery of Wadi al-Salam. Muhsin ‘Abd al-Sahib al-Muzaffar, in ‘Geographical and Historical Perspectives on Burial in the Najaf Area and Wadi al-Salam Cemetery’, provides us with a historical account of burial practice in Najaf and the beginnings of the extensive cemetery to which bodies are brought from all over the Shi‘i world. This practice is grounded in a belief that the Prophet Adam was the first to be entombed in the land that was to become Najaf. Such founding stories relate back to the pre-Islamic history of the city, giving it a temporal depth by which its current status is enhanced. The burial sites of non-Muslim communities (Christians in particular) show evidence of the long-standing practice of using this area as a burial ground. The current necropolis of Wadi al-Salam appears to date from the earliest periods of the city’s Islamic inhabitation, developing through the centuries to over 1,000 hectares and possibly 6 million burials by the early twenty-first century. Al-Muzaffar provides us with a detailed plan of the cemetery and the principal sites of importance, as well as a description of its development in the more recent past.

As al-Muzaffar’s account roots the burial of Imam ‘Ali in the history and practices of the Shi‘is, Paulo Pinto, in ‘The Noble City: Pilgrimage, Urban Charisma and Sacred Topography in Najaf’, explores the significance of the city in the pilgrimage practices of Shi‘is today. The cosmological significance of Najaf is exemplified by the historical events – both traceable and unverifiable – that form the city’s own narrative. These past events, and the characters who inhabit the stories, are made apparent to pilgrims through stories and rituals performed before, during and after their visit. The baraka, or blessing obtained by the pilgrim, is reinforced again and again by shrine visits – and the density of pilgrimage sites concentrates the baraka. Here the events of religious history predating the advent of Islam (concerning Adam, Noah, Hud and Salih) form part of a continuum of religious experience for the believer, leading up to the tombs of the great scholars of the Islamic era (from Shaykh al-Tusi to Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr, Muhammad Sadiq al-Sadr and the extensive Wadi al-Salam cemetery itself). This ‘sacred topology’ makes a pilgrimage not only a source of blessing, but also a framing for the history of the world. At the centre of the pilgrimage ritual, of course, lies the momentous events of the life and death of Imam ‘Ali. His tomb acts as a focal point in relation to which the other shrines of the city gain meaning. Pinto argues that the constellation of shrines, and the journey through them, gives the city a certain sacred charisma that propels it to a position of pre-eminence in the Shi‘i imagination.

In her essay ‘‘Ashura Rituals in Najaf: The Renewal of Expressive Modes in a Changing Urban and Social Landscape’, Géraldine Chatelard refocuses on the meaning of the city for its inhabitants by considering the commemoration of ‘Ashura in October 2016. She discusses the dynamics – particularly the city’s physical and social transformations – underlying the renewal of various expressive modes, the grounding of rituals in local culture and the degree to which they are embedded in the social and spatial fabric of the city and its environs. She describes and analyses some of them, notably the processions taking place in the Old City and the re-enactments of the Battle of Karbala and its aftermath as staged in small towns at the periphery of Najaf. She argues that there exists a contemporary Iraqi model of ‘Ashura rituals with the potential to become a reference amongst other Arab Shi‘i communities.

Najaf’s image as a ‘sacred city’ is thus created not only out of physical objects, but also from the manner in which those objects take on meaning for inhabitants and visitors alike. For those who may only visit the city once, these accorded meanings form an imagined as well as a real Najaf. Echoing the role of Jerusalem or Rome in Jewish and Christian thought, Najaf became a pivotal city for Shi‘i believers, around which the world could take on meaning. In some ways, the city’s prestige and position are created not through the reality of its significance, but the role it plays in Shi‘i history. How Najaf’s role in Shi‘i thought replicates these other sacred cities is a topic worthy of study, and these three essays will contribute to just this sort of grounded yet comparative enquiry in the future.

II: Knowledge, Culture and Religious Authority

The growth of the seminary complex, together with its various supporting institutions, has propelled Najaf from a pilgrimage site to an international power base. In many ways, the development of a seminary is a natural outgrowth of a pilgrimage centre, though that need not necessarily take place. There are instances of Shi‘i shrines where only limited seminary activity has developed, and been unable to maintain itself (one thinks of Samarra as the prime example). There are also examples of seminary activity without a shrine complex as its bulwark (e.g. southern Beirut). However, it is certainly the case that the most successful seminaries thrive in proximity to a major pilgrimage site, as there is a symbiotic relationship between pilgrims and the scholarly hierarchy. In the second section of the collection presented here, five studies introduce the operations of the seminary and the cultural institutions that have developed around it. The Najaf seminary system (hawza ‘ilmiyya, or ‘precinct of knowledge’) is a complex network of educational establishments that not only train students, but also provide cultural and intellectual capital for the international Shi‘i community. Najaf is normally considered the foremost such hawza in the Shi‘i world and, with the shrine of Imam ‘Ali, provides the city with the raw elements of its centrality in the Shi‘i geo-theology.

What characterises the Najaf hawza? In his chapter, ‘Najaf: Learned Authority and Scholarly Pre-eminence’, Robert Gleave explores three factors that have enabled the city to rise to its position and maintain it despite the challenges posed by Iraq’s recent political history. The ‘ulama form a hierarchy of individuals, often connected through marriage and family relationships, who together share a concern for the maintenance and promotion of the role of religion in society (as defined and controlled by the constraints of orthodoxy). As such, they present an alternative structure of authority that challenges the current political power, whether that power be Sunni, Shi‘i, Western, Arab, Turkish or Persian. Since the Safavid period, this relationship has been at the forefront of political debate, and a single position has yet to emerge. Najaf’s position clearly owes itself, to a greater or lesser extent, to the manner in which the scholars of the city have negotiated the fraught relationship with secular political power.

In particular, the relationship with Iran has proven fundamental to the city’s position, and this goes well beyond the injection of Safavid funds for the shrine and Nadir Shah’s subsequent gilding of its dome. Rather, the Iranian relationship since the Safavid period has been (and continues to be) adroitly played by the senior ‘ulama of Najaf. Aside from negotiating the political aspects of their role, Najafi scholars have projected their city to prominence by authoring the most important of the textbooks. In so doing, they have laid the groundwork not only for seminary training in Najaf, but elsewhere as well (most notably in Qom). Finally, the ability of Najaf to remain dynamic, even when appearing to be the most traditional of seminaries, has made it the location of choice for most students (tullab) of Shi‘i Islam. This ability may appear rooted in the past, yet it has constantly developed; it is not necessarily conscious sleight of hand by any individual, but rather reflects a mechanism built into Najaf’s hawza system that has, for example, enabled it to emerge from the wreckage of the 2003 Gulf War as the premium site for religious learning in Shi‘i Islam.

Sajad Jiyad’s ‘A Millenium in Najaf: the Hawza of Shaykh al-Tusi’ demonstrates how the history of Najaf has provided much cultural capital in securing its position. The hawza system today traces its origins to Shaykh al-Tusi and his relocation to Najaf from Baghdad in 1056 ce, following the destruction of the latter’s Shi‘i quarter and the burning of al-Tusi’s own house. Jiyad describes in detail the works al-Tusi produced and the institutions he founded, with a view to illustrating Najaf’s heritage. Al-Tusi’s shrine, as Pinto mentions in his own essay, is a site of pilgrimage for visiting Shi‘is, and the great scholar stands at the head of a long line of learned men claimed by Najaf as their own, who have defined Shi‘i scholarship for nearly a millennium. Understanding al-Tusi’s achievement is, in a sense, to understand his enduring legacy in modern Najaf.

The conceptualisation of the institutions that support the authority of the most senior scholars is explored in Sabrina Mervin’s ‘Writing the History of Religious Authority in Najaf: The Marja‘iyya as Apparatus’. Najaf is the seat of probably the most important internationally recognised Shi‘i scholars, and most Shi‘is in the international community turn to these individuals for guidance. Mervin analyses the organisation of their authority – known as the marja‘iyya – through the notion of a dispositif – a concept developed by Michel Foucault and often translated into English as ‘apparatus’. The idea is a broad one, applicable to a wide range of activity through which thought and cultural life might be understood. Mervin demonstrates that the various elements of the marja‘iyya (of which strictly scholarly activities form a small part) coalesce in a single system or network of relationships by which power is maintained and exercised, and provides the reader with a theoretical lens through which the powerful institution of the marja‘iyya – which dominates the Najafi intellectual and educational scene – might be viewed. She does so by analysing not only the historical institutions and activities of the scholars, but also their juristic ideational constructions (notions of legal derivation, the twin concepts of ijtihad and taqlid, the search for the most learned of the Shi‘is, and so forth).

The physical manifestation of Najaf’s legacy as a centre for education can be seen in the preservation of the physical apparatus of scholarship – namely, the libraries and manuscript collections within them. Muhammad Zuwayn outlines Najaf’s historical leadership in the preservation of cultural heritage in his essay ‘The Libraries of Najaf and Their Manuscript Heritage’. Iraq generally, and Najaf in particular, have long served as centres of religious learning; the primary artefacts of that learning – namely, books written and copied by the educated elite and their assistants – form a natural corollary to that tradition, and add a particularly rich layer to the history of the country. The practice of writing and copying books stretched back before Islam, embedding itself in the culture of Iraq and manifesting as a cultural trait of the people and their institutions. In the more recent past, Najaf has exhibited this trait through the cultivation of important manuscript collections. Zuwayn catalogues the collections of various institutions, with a particular focus on the Imam ‘Ali Shrine Library, the Imam Hassan Library and the Al Kashif al-Ghita’ Library. In addition to these centres, many smaller manuscript holdings survive, which are often little known or consulted by researchers. Within the wealth of detail Zuwayn provides, the reader will discover the overall story of the records of a scholarly community, what was important at particular times and how a continuity of scholarship has been maintained through the ages.

The final essay in this second section is by Hassan Nadhem, and reflects on the manner in which the history and culture of Najaf have been recorded by historians in the past. His essay, ‘The Historiography of Najaf: A Study of Encyclopaedic Works’, outlines the various structural and generic techniques used by historiographers of Najaf to describe their subject. These were not always scholars within the religious seminary, though they always had an awareness and sympathy for the religious position and role of the city. A number of important books are described, providing an essential resource for historians of Najaf. Some of these works, such as al-Dujayli’s Mawsu‘at al-Najaf al-ashraf mentioned above, include the most important sources that Western historians have homed in on when preparing their work. The journal Afaq najafiyya (The Environs of Najaf), published by Kamil Salman al-Juburi, is also listed as a useful source.

Having laid out the sources, Nadhem outlines the concerns that present themselves to the historian when composing a history of Najaf. These are similar to those outlined above, with the issues of myth and history being particularly noteworthy, as well as the need for precise historical data when none is present. He ends with a critical recognition of the need for a new history of Najaf, perhaps authored by someone from outside Najafi circles who may not be influenced by an overarching respect for the city’s accomplishments, but who is admiring of its role in history and its value as a topic for scholarship all the same.

The religious culture and institutions of Najaf have grown up, in part, because of the shrine of Imam ‘Ali, but soon took on a life of their own and developed independently. They have become a self-subsistent system in which each generation of scholars can train the next, and maintain the authority of the scholarly class within the Shi‘i community. Yet there is a need for deeper levels of analysis of this system, and wider recognition of its component parts, from libraries to teaching circles, history to historiography. The contributions in this section demonstrate that the hawza and the marja‘iyya have developed a set of ‘coping mechanisms’ whereby they might preserve their authority in the future.

III: Contemporary Developments

Predicting the future development of Najaf within the region is a challenge that most scholars shy away from. In our third and final section, we examine the ways in which Najaf has developed in response to contemporary events; from this, perhaps we shall be able to recognise how the city might develop in the future. This is a precarious business, and the success of any analysis must rely on solid historical research. It is this grounding that we aim to present in the final essays of this collection.

Robert Riggs’s ‘Najaf: A Historical Centre of Power and Economy (1500–1920)’ outlines how the city became a commercial centre, a position that ran alongside its status as a centre of scholarship. The Imam ‘Ali Shrine once again shows itself as essential to wealth accumulation in the city. Riggs goes back into the history of Najaf in order to establish how wealth transfer mechanisms were established in the Shi‘i community, and how these moved into the modern period as elements of a burgeoning financial system. These were not primarily through waqf (endowments), Riggs argues; although these endowments were recognised as major sources of wealth throughout the Islamic world – particularly for scholars, to whom they were often dedicated – in Najaf, the prime source of wealth comprised transfers of religious taxes to the scholarly elite. The most famous of these was, of course, the khums payment, but other voluntary payments operated in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries as well. The Awadh Bequest, which originated in the Shi‘i principality within largely British-ruled India, and which Riggs outlines in some detail, was an important example of such a transfer to Najaf of funds from the global Shi‘i community. Burial rites and the relocation of bodies to Najaf for interment also contributed to Najaf’s build-up of capital. The close relationship between the ‘ulama and the bazaari merchant class also reinforced the financial structures that enabled Najaf to survive comparatively lean periods of dictatorship, and prepared it well for its re-emergence in the post-Saddam Hussein era.

If the financial footing of Najaf was developed over some centuries, the major challenge of the twentieth century was how to respond to the new threat of foreign occupation. The 1918 revolt in the city against British colonial occupation has a special place in the self-definition of Najaf as a Shi‘i stronghold. Abbas Kadhim, in ‘The Najaf Revolt of 1918: Its Importance and Potential, and the Causes of Its Collapse’, compares this event with the later ‘revolution’ of 1920, which has been studied more deeply. The events of the revolt are laid out in detail, and they appear as a sort of dress rehearsal for the 1920 revolution, which engulfed the south and not only Najaf. Kadhim also provides important context regarding the preceding World War One, when Shi‘i authorities seemed to side initially with the British against Iraq’s former rulers, the Ottoman Turks, but then saw their antipathy grow towards the new military rulers. The lessons learned in Najaf after the failed revolt of 1918 were put to use, and greater success was attained later; moreover, the deep involvement of the ‘ulama with the political machinations of the city’s elders (both tribal and otherwise) prepared them for future power-broking.

Coinciding with the revolt in the south at the end of World War One was, of course, the emergence of communism as an international force and as a challenge to established intellectual structures. Fouad Kadhem, in ‘Communism in Najaf: The Rise and Fall of a Secular Movement Between 1918 and 1963’, examines how the city responded to the growing communist presence in its midst during the middle part of the twentieth century. The popularity of Marxist ideas amongst the youth of Najaf is as evident as it was elsewhere in the Muslim world. The loss of confidence in religion to provide an effective programme of resistance is well documented – but Kadhem’s analysis supplements these insights with a study of how Shi‘i communists used Shi‘i networks and ideas to recruit, and to attempt a level of authenticity. Shi‘i organisations were a good base from which to develop the communist cell structure and ultimately a political party, with Najaf contributing to the Iraqi Communist Party (ICP) in great number. The response of the ‘ulama was particularly interesting, Kadhem notes, because of an obvious paradox: one might have expected religious figures to distance themselves from an atheist doctrine such as communism, but many of them supported the aims of the ICP whilst also being concerned about its hold on youth. Kadhem then considers and analyses how, in the post-independence period, pan-Arabism and Iraqi nationalism fought against and gradually weakened the Communist forces in Najaf, with varying degrees of support from the Shi‘i clerical leadership.

How fanciful is it to say that Najaf has a ‘personality’? The studies presented here take the city as their subject, and in different ways they try to work through how that character might be perceived (or, perhaps, constructed). Without a doubt, there is a sense when examining the Arabic-language scholarship on the city that the most appropriate literary device is to treat the city as deserving of a biography. This is, in part, on account of the localism that has characterised much Arab (and, more broadly, Muslim) historical writing; but it is perhaps more than this. in that Najaf – with its extensive symbolic and historical significance – has taken on a personality, which in turn is reinforced by successive generations of writers, politicians and cultural commentators. Whether or not this is an appropriate methodology for a collection of scholarly articles is one of the questions we have tested in this book. Its success is not yet clear, as this is merely a collection of studies, sometimes experimental and speculative, about how geographical focus might provide thematic unity. Put another way, by gathering together chapters that all focus on the same city, might we learn something more than just the conclusions of individual chapters? The symbolic meaning enveloping Najaf reflects its imagined role in the effective maintenance of the Shi‘i faith, and its imagined history is as important in assessing its significance as its actual historical role. That is the challenge facing historians and social scientists, which the current collection has addressed, and which we hope has laid the ground for future study of Najaf and its contribution to the religious life of the broader global Shi‘i community.

Sabrina Mervin and Robert Gleave, 2016

PART I: A SACRED CITY

1 The Foundation of Three Cities: Hira, Kufa and Najaf

Alastair Northedge

It is not difficult to regard Hira, Kufa and Najaf as a complex of three successive cities, all occupying the same site – or nearly so. Such complexes are common: in India, Delhi is situated on seven different sites; in Egypt, Cairo succeeded Fustat on an adjacent one. In our case, the three sites are considered different cities – but they are not. The one succeeded the other, and the two sites of Kufa and Najaf have both survived until today (The site of Hira is adjacent to Kufa, which itself is adjacent to Najaf.)

The site for these successive conurbations is a desert plateau between the Euphrates and the depression of the Bahr Najaf, some 60 km south of ancient Babylon and Hilla, capital of the modern governorate of Babil, 145 km south of Baghdad. It is a peninsula, an extension of the flat Western Desert of Iraq raised above the surrounding flood plain. It was no doubt chosen as uncultivable land, close to the farmlands but in contact with the desert. The earliest site, Hira, is located on the narrow point of the peninsula some 5 km wide. Kufa and Najaf are situated on a wider part of the peninsula, where it is 9 km wide. On the east side, close to Kufa, lies the western Hindiyya channel of the Euphrates, and the city of Kufa was probably never far away. For al-Jahiz, the ninth-century ce ‘Abbasid writer and thinker, this branch was known as Nahr Kufa – the ‘River of Kufa’.1 On the west side of the zone is the depression of Bahr Najaf, which connects with the Euphrates plain just to the south at Abu Sukhayr. Today the depression is cultivated, though it may have been marshy in the past. Only to the north does the plateau link to the Western Desert of Iraq.

So far, we lack evidence of early occupation of the area, though that may yet appear. Rather, occupation appears to date to the early centuries of the Christian era.

Hira

The name ‘Hira’ is our main evidence for the foundation of the site. It is derived from the Syriac hyrta, meaning a camp, and is related to the Arabic hayr, meaning a reserve. It may have been founded in the third century ce, though no foundation date is really known.2

Hira was the city of the people known in the West as the Lakhmids and as al-Manadhira in Iraq, after the ancient royal family of al-Mundhir. The Lakhmids constituted a pre-Islamic Christian kingdom in what is now Iraq, and were, in fact, the Nasrid family from the tribe of Lakhm. ‘Amr bin ‘Adi emerged from this tribe in the third century ce and founded Hira. (This was a period of great change in the Arab world, with the collapse of the incense trade in the Arabian Peninsula and the formation of the system of Arab tribes known at the time of the Prophet, which has survived into the present day.) He was succeeded by his son, Imru’ al-Qays, who is described in the famous al-Namara inscription from southern Syria as ‘King of all the Arabs’, and who was buried in 328 ce.3 The prince mentioned as the father of the Imru’ al-Qays buried in Syria may not be the same amir of Hira, but the flavour of the times is given. ‘King of all the Arabs’ could refer to someone who claimed to be chief of a confederation of tribes.

There is a gap in the record until just before the advent of Islam. The fifth century is much better documented in Greek and Syriac sources as well as Arabic sources, which yield important data on three Lakhmid kings. The first is al-Nu‘man, nicknamed ‘al-A‘war’ (‘the One-eyed’), and also al-Sa’ih (‘the Wanderer’); according to the Arabic tradition, he earned the latter nickname because he had renounced the world. He was succeeded by his son al-Mundhir, who is said to have reigned for forty-four years (possibly 418–52 ce). Much more is known about the warrior-king al-Nu‘man II, who took part in the Byzantine–Persian wars of the period. In 498 he was vanquished by the Byzantine commander Eugenius at Bithrapsos; in 502 he advanced against Harran, located in what is now southeastern Turkey. There he was first defeated by the Romans, then triumphed over them.

The last period is dominated by al-Mundhir III, who reigned for half a century (503–54 ce). It is characterised by an association between al-Mundhir III and the Sasanian kings. The last Lakhmid king was al-Nu‘man, son of al-Mundhir IV, who ruled for some twenty years (580–602 ce). However, Khusraw Parviz (598–628 ce), the last great king of the Sasanian Empire, had a poor relationship with the Arabs, and suppressed the Lakhmid dynasty despite the fact that they had served the function of maintaining amicable relations with neighbouring Arab tribes.

The political function of Hira for the Sasanian dynasty was connected with the protection of the western frontier against the Arab tribes. Sasanian policy towards the tribes had two prongs – one military and one political. The military approach was to build fortifications. Shapur II (309–79 ce) built a series of frontier defences, mainly intended as strongholds against the Bedouin.4 The fourth-century defences were extended into a Sasanian version of Roman frontier defences (Latin: limes) by Khusraw Anushirvan (531–78 ce), and forts attributed to this scheme have been identified.5 According to the scholar Yaqut al-Hamawi (d. 1229):

The khandaq (moat or fosse) of Shapur is in the plain of Kufa. Shapur dug it between himself and the Arabs for fear of their depredations … Then when Anushirvan ruled he was informed that certain tribes of the Arabs were attacking what was near the desert of the Sawad. Then he ordered the marking off of a wall belonging to a town called al-Nasr which Shapur had built and fortified to protect what was adjacent to the desert. And he (Anushirvan) ordered a fosse dug from Hit and passing through the edge of the desert to Kazime and beyond Basra reaching to the sea. He built on it towers and pavilions, and he joined it together with fortified points. The reason for that was to hinder the people of the desert from the Sawad.6

The political approach was to employ the Lakhmids as intermediaries to conduct diplomacy in the desert. Although there may have been an Iranian marzuban (frontier governor) there, from the third century the Lakhmids are described in Arabic sources as ‘ummal – agents – who conducted a complex policy with regard to tribes further away.7 The Lakhmids appear to have derived their revenue from taxes on the tribes and from lands awarded to them in southern Iraq.

In the equivalent case on the Byzantine frontier, the Byzantines financed the Ghassanids with gold to run the frontier for them. (Like the Lakhmids, the Ghassanids were Christian Arabs, although in their case they had migrated to the area of Mesopotamia only in the third century ce.) It is not known whether or not the Lakhmids received gold, but no doubt the Persians felt that they cost too much to support and were too unruly. Still, the policy was cheaper than defending the Sasanian Empire by military means. At any rate, the dynasty was suppressed, and the frontier left open to Muslim Arab attacks.

The city of Hira has not been properly studied archaeologically. There was an expedition from Oxford in 1931–34, and its map documents sixteen separated mounds; however, it does not define the limits of the city, nor does it explain what was between the mounds.8 It is very difficult today to locate the mounds of which it speaks, although some mounds, still visible, can be identified. In the excavated mounds, they found two churches and a secular residence, constructed within an earlier fort. Subsequently, a number of missions from the Iraqi Directorate-General of Antiquities and Heritage conducted excavations after 1945. In 1956, Tell Umm ‘Arif was excavated, while in 1981 the cemetery was examined.

In 1990, a French expedition began work on the site but was ejected after three days, for political reasons. It had only been able to assemble a collection of potsherds.9 Later, an airstrip was laid near to or across the northern part of the site in order to provide Najaf with an airport. In 2010, the Iraqi State Board of Antiquities was able to excavate a section south of the runway, in between the mounds of the 1930s; there they found buildings of the early ‘Abbasid period (end of the eighth century ce).10

It is difficult to assess the extent of the site, of which only a certain number of mounds are known. One estimate suggests the mounds are scattered over 25 km², but that may include the gardens that extended southeast to Abu Sukhayr. Thirteen principal mounds were identified by the original Oxford expedition, and the question remained open as to what existed between them. The open nature of the city is attested to by the ninth-century ce Persian historian and geographer al-Baladhuri, who wrote that the invaders who conquered the city rode round on horseback in the open spaces among the buildings; but the work of 2010 also found buildings between the mounds. No doubt it was partly built up, but there was no limit defined by fortifications.

Mound I contained a two-storey residence consisting of an earlier quadrilateral enclosure wall, in which an early ‘Abbasid courtyard building is inserted. The excavators concluded that the ground floor was not a living space, although decorated, and that the living quarters must have been on the first floor. The stucco decoration is that of the vine-leaf style, dating to the late eighth century ce. The plan has two iwans (rectangular halls with one of four sides left entirely open) facing one another across a courtyard.

In Mound V was found a large basilica, oriented towards the southeast. The building is made of mud-brick, but the floor of fired-brick tiles, and the walls were covered with lime plaster. The apse is rectangular, like many early churches in Iraq. There was a bema, or raised platform, in the middle of the nave, but it was not fully studied. There were wall-paintings in the apse, in two layers on top of one another, with at least a depiction of a cross in the upper layer.

A second church was discovered buried in Mound XI. In this case, the entire church was excavated, and again there was a rectangular apse almost closed off from the nave. The nave roof was carried on fired-brick piers and arches. The flooring was of fired-brick tiles, and in the centre of the nave there was a bema, frequently also found in Syrian early church architecture. The Iraqi expedition of 2010 excavated an area of buildings close to the runway of the airport. Here again there were stucco panels of the vine-leaf style dating to the end of the eighth or beginning of the ninth century. Two areas were excavated, representing three dwelling units. The largest is a substantial house with a four-iwan plan.

Lastly, the French expedition of 1990 found a zone of pottery kilns 800 m from the road linking Najaf to Abu Sukhayr. While some of the pottery may be of the late eighth or ninth century, it is clear that there isglazed pottery dating to the early tenth century ce.

Two famous castles are known at Hira from the texts, though their sites have not been identified with any certainty: al-Khawarnaq and al-Sadir. Al-Khawarnaq was first constructed by the tribe of ‘Iyad, but built up by the Lakhmid ruler al-Nu‘man at the beginning of the fifth century ce. King Khusraw Parviz of the Sasanians stayed there in 611, at the time of the battle of Dhu Qar. The castle was later rebuilt by the ‘Abbasids. The site is said to be located close to the road to Abu Sukhayr. The site could be similar to that excavated at Mound I, by the sequence of events, but there is no proof. The ‘castles’ may not have been larger than that. The Christian princesses of the dynasty also built monasteries, of which the most famous is Dayr Hind. One or the other might be identified at the excavated churches, but as the excavations did not extend beyond the church itself, it is impossible to say whether they were attached to monasteries.

The city plan has precedents in the Arabian Peninsula.11 At al-Dur12 in Umm al-Quwain (the smallest of the seven emirates that constitute the United Arab Emirates), we find a similar plan of widely spaced mounds dating to the third century ce. Again, little is known about what was situated between them. One could argue that the widespread settlements among the palm plantations known from the time of the Prophet at Madinah also represent the same model.13 Tribal castles of the type mentioned at Hira could well be similar to what is found in the Arabian Peninsula.14 Other Peninsular examples in addition to that at al-Dur can be found at Qaryat al-Faw (Saudi Arabia), Mleiha (UAE) and Tayma (Saudi Arabia), dated to the fourth century ce. No later pre-Islamic tribal castles have been found, no doubt because, as has been recently demonstrated, there was an economic decline in the Gulf during the fifth and sixth centuries ce. The only trace of their existence remains in pre-Islamic poetry, but such castles played an important role under the ‘Umayyad caliphs in Syria (first half of the eighth century). The same practice was carried over into Kufa, with the spaces filled in by houses of the fighters (al-muqatila), and a palace-mosque at the centre.

Kufa

Kufa has its origins as an outlying sector of Hira, situated to the northeast. Some modern scholarship says that settlement in Hira moved over time from the southwest towards the northeast and the site of Kufa, but the basis of this idea is not well demonstrated, as little is known on the ground. Kufa is described by the ninth-century geographer Ahmad al-Ya‘qubi as ‘three miles’ (5.2 km) from Hira, and this seems approximately correct.15

At any rate, Kufa was founded in 638 ce by Sa‘d ibn Abi Waqqas, the victor of the battle of Qadisiyya, which brought Iraq under Muslim sway. After the battle, the Sasanian capital of al-Mada’in and the western city of al-Anbar were thought to be too mosquito-ridden for the Muslim cantonments, while the raised plateau of Hira was thought to be healthier. A second factor in the choice of site, although one not mentioned by the sources, could be the wisdom of building outside limited fertile land on the desert plateau (as in Ancient Egypt).

While there are few explicit statements about what the earliest city was built of, it is evident that it must have been composed of tents and reed huts. Al-Baladhuri tells us that Sa‘d’s enclosure had a wooden door and a fence of reeds.16 But construction in mud-brick must have started early,17 and the mosque was rebuilt in fired brick in 670 ce.

The best description of early Kufa is given by the Islamic historian Sayf bin ‘Umar (d. 796 ce).18 In this text, he describes Kufa as having a mosque at its centre, with a prayer hall built from columns taken from Hira. The open area was defined by a ditch. According to the latest scholarship, the mosque may have only consisted of the prayer hall, while the open square had multiple functions, being both a place of prayer and a market.19 The site was marked out by an archer firing a bow-shot (ghalwa), about 240 m in each direction.20

Outside the central square, fifteen manahij (avenues) separating the tribal lots, each forty cubits wide, radiated from this central area. Along the five manahij of the north were settled the tribes of Sulaym, Thaqif, Hamdan, Bajila, Taghlib and Taym al-Lat; to the south, the Asad, Nakha‘, Kinda and Azd; to the east, the Ansar, Muzayna, Tamim and Muharib, Asad and ‘Amir; finally, to the west, Bajala, Bajla, Jadila and Juhayna. (Most of these peoples arrived from the Arabian Peninsula and were settled in Kufa to serve as fighters [muqatila].) Changes and movements surely occurred later, however, and the list we have now is unlikely to be complete.

Around 643–4 ce, Caliph ‘Umar ibn al-Khattab is said to have instituted a diwan or register of the muqatila, in which the individual’s pay (ata) and rights to food supply (rizq) were registered. Caliph ‘Ali bin Abi Talib was able to mobilise the whole force of Kufa to fight the ‘Umayyad Mu‘awiya – 57,000 muqatila, of whom 40,000 were adults and 17,000 youths. Later, the number went up to 60–70,000, to which must be added the families and non-fighters.

A good number of elite residences are mentioned, and we can imagine they were the centres. The allotments were called khitat – or, if allotted to an individual, qati‘a – and the residences were called ‘house’ (dar) rather than ‘castle’. Al-Ya‘qubi gives a list of twenty-five noble residences. It may be that al-Ya‘qubi, who lived in the second half of the ninth century, was more familiar with the houses of the elite in Baghdad and Samarra, and used the terminology of his time for buildings closer to the style of the castles of Hira.

In addition, there was a series of a dozen open spaces called jabbana. These were probably used as tribal cemeteries, but also as places of assembly. The Kunasa was a large open area west of the town, used first as a dumping ground, then as an animal market, then as a place of execution and finally as an unloading place for caravans.

After the death of ‘Ali in 661, Mu‘awiya – now the fifth caliph – signed a treaty with the son of ‘Ali, Hassan, according to which the latter abdicated his right to the caliphate to avoid an open war among Muslims. Hence Kufa fell under ‘Umayyad rule. In 670–3 ce