Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

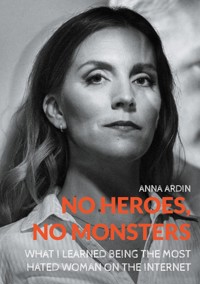

No Heroes, No Monsters focuses on the dramatic struggle of Anna Ardin, the WikiLeaks activist who, in 2010, came forward to report sexual abuse by Julian Assange. This is her testimony to a legal trial that was replaced by an Internet tribunal. A tribunal where women's rights are all too often both neglected and weaponized. A tribunal that every day of the year chooses a new woman to be the most hated. The book goes beyond the headlines - the black and white pictures of heroes or monsters - and emphasizes the need to acknowledge the shades of gray. In the book Ardin navigates through her personal life, the sexual assault charges, the media frenzy and the extensive hatred that followed from accusing a popular man, as well as through the unfair accusations of Chelsea Manning and WikiLeaks. Ardin's story is a call for justice for everyone abused, holding even important people accountable. It's a powerful compilation of the feminist lessons Ardin learned from living, for over a decade, in the shadow of the "hero" myth.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 418

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For the feminists, every single one of you

A wise woman wishes to be no one’s enemy; a wise woman refuses to be anyone’s victim.

Maya Angelou

I am one of the two women who, in 2010, told the police that Julian Assange had sexually assaulted us. WikiLeaks fans worldwide—certainly myself very much included—probably wish I’d had no reason to make my report, but I did. Of course, I didn’t know the legal terminology for what had happened, but to me, it was an assault, and I will continue to call it that.

For his work with WikiLeaks, however, Julian Assange was accused of something else entirely: espionage. These accusations are unjust and have more to do with truth, transparency, and freedom of speech. On the other hand, the sexual assault accusations are not related to espionage or free speech but rather to his personal behavior. That behavior and the debate following the police report ultimately concern women’s rights. Should popular and powerful men be allowed to behave however they want toward women or not?

These are two separate accusations that have nothing to do with each other. I am not accusing WikiLeaks of assault, and WikiLeaks’ work is hardly furthered by allowing its representatives to behave however they please.

I was convinced that WikiLeaks was doing important work for peace and openness. That was why I worked to have Julian Assange come to Stockholm and speak, and that was why I let him stay in my apartment. He assaulted me in that context. Only a few days later, he spent the night at the place of another woman who later testified he did something similar to her. It was a coincidence that we happened to get in touch with each other, but I didn’t want to leave her defenseless. So, I went with her to the police and gave a statement about how he had behaved toward me. It sounds dull, but that was the limited extent of my involvement in the case.

During these years, two tribunals have been held to settle the question of guilt and investigate the truth in our accusations of sexual offenses: one official legal tribunal via the police and the courts and another via discussion forums on the internet and in the press. This experience is precisely what this book is about— the official legal process Julian refused to participate in and the media frenzy Julian was active in, which I did everything I could to avoid for ten years.

I haven’t had the least involvement in what the various prosecutors, defense attorneys, governments, and PR agencies have done. I have waited and listened. I cooperated when the police and prosecutors asked questions. I testified on a few occasions about the harassment that followed the report, but to avoid influencing the legal process, I have not spoken publicly for all these years about the actual events.

We will never know if Julian is legally an offender, but I can describe the events as I experienced them. Instead of testifying in the trial that never took place, I would like to tell my version here, like this. Perhaps this case will illustrate the dialogue we must all keep open about gray areas and assault. I am just one of the millions of women who have not been respected. This is a book about what it was like to be behind the headlines during a decade-long media frenzy and how the hate online affected me after reporting my experiences of an assault. This is an account without angels or monsters, where heroes can be villains and where truths may be hidden somewhere in the nuances between black and white.

My goal is to be completely honest and transparent with this book. I have double-checked my memories with the help of journal entries and other previously unpublished texts, as well as interviews, conversations with other people who were there, newspaper articles, and by searching various online forums. I have done my best to reproduce the sequence of events and their order correctly. At the same time, of course, it is a fact that most of this happened many years ago. What day a specific thing occurred or the wording of an exchange may not be exact, but it is as close as I can ever get. All of the quotes from anonymous trolls are authentic and illustrate the hatred and threats directed at me during various periods. Still, these comments may have ended up under a different date in this book than on which they were initially written.

Thank you for reading.

Anna Ardin

Table of Contents

Dedication

Epigraph

About the book

2010

Tuesday, August 10, 2010

Wednesday, August 11, 2010

Thursday, August 12, 2010

Friday, August 13, 2010

Saturday, August 14, 2010

Saturday, August 14, 2010, Evening

Sunday, August 15, 2010

Monday, August 16, 2010

Tuesday, August 17, 2010

Wednesday, August 18, 2010

Thursday, August 19, 2010

Friday, August 20, 2010

Saturday, August 21, 2010

Sunday, August 22, 2010

August 23, 2010

August 24, 2010

August 25, 2010

August 26, 2010

August 27, 2010

August 28, 2010

August 29, 2010

August 30, 2010

August 31, 2010

September 1, 2010

September 3, 2010

September 4, 2010

September 6, 2010

September 7, 2010

September 8, 2010

September 9, 2010

September 12, 2010

September 16, 2010

September 19, 2010

September 22, 2010

September 27, 2010

October 15, 2010

October 18, 2010

October 19, 2010

October 22, 2010

November 13, 2010

November 16, 2010

November 18, 2010

November 20, 2010

November 22, 2010

November 24, 2010

November 28, 2010

November 30, 2010

December 2, 2010

December 5, 2010

December 6, 2010

December 7, 2010

December 8, 2010

December 9, 2010

December 10, 2010

December 11, 2010

December 12, 2010

December 13, 2010

December 14, 2010

December 15, 2010

December 16, 2010

December 18, 2010

December 19, 2010

December 20, 2010

December 21, 2010

December 22, 2010

December 23, 2010

December 24, 2010

December 26, 2010

December 27, 2010

December 31, 2010

2011

January 1st, 2011

January 2, 2011

January 4, 2011

January 5, 2011

January 7, 2011

January 8, 2011

January 9, 2011

January 13, 2011

January 17, 2011

January 25, 2011

January 26, 2011

January 27, 2011

January 28, 2011

February 1, 2011

February 7, 2011

February 12, 2011

February 17, 2011

February 18, 2011

February 24, 2011

March 1, 2011

March 2, 2011

March 7, 2011

March 14, 2011

March 19, 2011

April 24, 2011

April 26, 2011

April 27, 2011

May 14, 2011

May 18, 2011

May 23, 2011

May 25, 2011

July 8, 2011

July 18, 2011

July 21, 2011

July 27, 2011

August 10, 2011

August 11, 2011

August 15, 2011

August 18, 2011

August 20, 2011

October 1, 2011

October 2, 2011

October 6, 2011

October 11, 2011

October 12, 2011

October 14, 2011

October 23, 2011

October 24, 2011

November 11, 2011

November 21, 2011

November 24, 2011

November 26, 2011

2012

February 7, 2012

February 29, 2012

March 30, 2012

May 4, 2012

May 30, 2012

May 31, 2012

June 3, 2012

June 14, 2012

June 19, 2012

June 20, 2012

July 17, 2012

August 3, 2012

August 16, 2012

August 21, 2012

October 20, 2012

October 29, 2012

December 9, 2012

December 12, 2012

December 16, 2012

2013

January 10, 2013

January 21, 2013

February 28, 2013

March 6, 2013

April 13, 2013

June 10, 2013

July 30, 2013

August 21, 2013

August 22, 2013

September 13, 2013

September 15, 2013

November 23, 2013

December 6, 2013

December 9, 2013

December 28, 2013

2014

March 6, 2014

July 16, 2014

July 30, 2014

August 31, 2014

November 20, 2014

December 8, 2014

December 21, 2014

2015

January 8, 2015

March 13, 2015

April 16, 2015

May 9, 2015

May 11, 2015

May 29, 2015

June 16–17, 2015

August 13, 2015

August 17, 2015

December 22, 2015

2016

January 21, 2016

February 4, 2016

February 5, 2016

February 22, 2016

February 26, 2016

March 8, 2016

March 31, 2016

April 2, 2016

May 25, 2016

May 28, 2016

July 19, 2016

July 28, 2016

August 8, 2016

August 9, 2016

August 22, 2016

August 24, 2016

September 16, 2016

October 28, 2016

November 8, 2016

November 9, 2016

November 14, 2016

2017

January 17, 2017

April 7, 2017

May 17, 2017

May 18, 2017

May 19, 2017

May 20, 2017

June 9, 2017

August 14, 2017

October 16, 2017

November 14, 2017

2018

May 25, 2018

September 17, 2018

October 16, 2018

2019

February 18, 2019

March 8, 2019

March 10, 2019

March 22, 2019

March 29, 2019

April 11, 2019

April 12, 2019

May 7, 2019

May 8, 2019

May 13, 2019

May 20, 2019

May 23, 2019

May 29, 2019

June 2, 2019

June 6, 2019

July 22, 2019

July 31, 2019

August 1, 2019

September 9, 2019

September 26, 2019

September 27, 2019

November 13, 2019

November 14, 2019

November 19, 2019

November 20, 2019

November 22, 2019

December 9, 2019

2020

February 18, 2020

February 19, 2020

February 21, 2020

February 22, 2020

February 24, 2020

February 25, 2020

March 8, 2020

March 9, 2020

Acknowledgements

Sources

Quotes

Notes

Copyright

2010

Tuesday, August 10, 2010

“The founder of WikiLeaks wants to come to Sweden. Do you want to invite him and arrange a seminar?”

This question comes from a journalist named Donald and is put to the Religious Social Democrats of Sweden, an organization that is both my job and fills my spare time. We have had several interactions with Donald thanks to our shared commitment to human rights in Palestine, but his connection to WikiLeaks is news to us.

WikiLeaks is an organization that contributed to two leaks that attracted a great deal of attention during the spring and summer. Collateral Murder was published in April. It is a shaky film from a military helicopter in which American soldiers film each other shooting at Iraqi civilians and kill 15 people, two of whom are Reuters reporters. At the end of July, WikiLeaks contributed to “Afghanistan Leaks,” a large number of classified military documents about U.S. warfare in Afghanistan, released simultaneously in The Guardian, The New York Times, and other media outlets worldwide.

It is not a coincidence that Donald calls us specifically, asking whether we want to hold a seminar with WikiLeaks. After 80 years of agitating for peace, the Religious Social Democrats of Sweden have demonstrated and protested against the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. They have been called the Brotherhood Movement, named after Brotherhood, a newspaper first published in 1927, and have worked for human dignity and respect of God’s creation since then. Therefore, they are an obvious ally in work against war crimes.

The footage and documents that WikiLeaks leaked this year are even more unacceptable to us but have become substantial proof of the immorality of the U.S. during the war. Mercenary soldiers financed by the U.S. government have committed serious human rights abuses. The number of civilian casualties in Iraq is probably many times higher than reported, and espionage and kickbacks clearly play a crucial role in international diplomacy. These are problems that need to be brought to daylight to be solved and issues that are now being discussed broadly, thanks to WikiLeaks.

But these things are essential not only to the Religious Social Democrats but also to me personally. I am pro-liberty and a Social Democrat. I dislike the authorities and hate imperialism and wars of aggression. I condemn jailing people for their political views and not giving dissidents fair trials. I abhor that the West clothes its plundering wars regarding development, fighting terrorism, and promoting women’s rights—even though the effects sooner increase terrorism and set women’s rights back. And in all of this, equitable peace in the Middle East has felt particularly important since recently seeing, in person and with my own eyes, the misery and hopelessness inside the world’s largest outdoor prison, the utterly bombed-out Gaza. WikiLeaks seems to stand for the same things and wants to expose the abuses of power that underlie the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, regardless of the terms they are couched in.

However, I’ve never heard of Julian Assange, and I don’t understand what it means to be the founder of WikiLeaks. For example, where’s the secretary-general, the director, or the chairperson? But regardless, it’s evidently something cool. The footage from the Apache helicopter is enough of an argument.

My boss says yes to Donald’s query, and we decide to call the seminar “The Truth Is the First Casualty of War,” as British women’s suffrage activist Ethel Annakin Snowden memorably put it in 1915 when she criticized the use of women’s rights to argue for war during World War I. 1 Waging war requires lies— mythmaking and propaganda about the enemy being different, an eviler sort of people who threaten us— and the censorship of information regarding the war’s actual consequences. The truth is rarely simple, obvious, or absolute, but striving for it is always a precondition for peace and justice.

I arrange Julian Assange’s trip from London to Stockholm with the help of Donald, our organization’s chairperson Peter, the president of our youth wing, Victor, and a Swedish-Israeli journalist, Johannes, WikiLeaks’ contact person in England. I also arrange for us to borrow the Swedish Trade Union Confederation Hall for the seminar, send out the press release, and invite people. Everything happens very quickly. Both time and financial resources are tight.

Assange’s plane ticket costs more than we can afford, but we decide it is worth prioritizing this. The visit will draw attention to issues of international solidarity, ending the war, and possibly placing all the troops in Afghanistan under UN command. Among the more knowledgeable people in our circles—peace activists and people who work for truth and transparency—many are familiar with WikiLeaks and view it as a symbol of righteous resistance.

We also find out that WikiLeaks is interested in starting the publication of an online newspaper in Swedish in order to benefit from Sweden’s strong protections for freedom of expression and freedom of the press. So, we begin discussing the options for supporting WikiLeaks as it establishes itself in Sweden as an organization and publication.

The seminar we are arranging is scheduled for the morning of August 14. Julian Assange will arrive on Thursday, August 12, and we are responsible for his accommodations for two nights in connection with the seminar, i.e., August 12 and 13. He would prefer not to stay at a hotel, he informs us, but rather live as secretly as possible. Since I will be away working at a festival those nights anyway, I offer to loan out my studio apartment in central Stockholm. The price is right for our financially strained organization, and it will be secret—the way Julian wants it—while also giving me some status. I will get to be in the thick of things and know the people being discussed. It will be a status marker more valuable in my circles than earning a large salary, owning an environmentally friendly car, or any of the other usual indicators.

Wednesday, August 11, 2010

There is an enormous amount of interest in the seminar. In the press release, we write that journalists have priority, but so many journalists sign up there’s almost no room for anyone else. I need to turn away hundreds of people.

Maria, a young woman who reads about the seminar on Twitter, gets in touch. In her message, she writes she can volunteer and help with whatever might be needed if it means she can attend. Her help feels very welcome amid the stress of organizing everything. I reply that we don’t currently have any volunteer assignments, but something might suddenly come up. If she can be there well in advance and stand by just in case, then she is welcome to attend.

Thursday, August 12, 2010

A Christian youth festival called Free Zone (Swedish Frizon) is being held in Kumla, a couple of hours west of Stockholm, which I am attending as a representative of the Young Christian Left (Ung kristen vänster). I staff our information tent along with a few other people. We talk to young people interested in international solidarity, religious freedom, how all people are equally valuable, and caring for all creation. In a talk on stage about Christianity, politics, faith and solidarity, Christian anarchists rebuke me for not being radical enough. But out among the festival attendees, we’re also forced to debate teenage Creationists (who say things like “you may have monkeys in your family, but I don’t”), opponents of abortion, and people triggered by our very presence there—primarily because the Christian Social Democrats, in particular, were instrumental in convincing the Church of Sweden to allow same-sex marriages just over a year earlier. But worst of all, I meet young people who seem to have been trained to divide the world between them and us, using religion as an argument.

While we’re there, the WikiLeaks spokesperson picks up an envelope with the key to my apartment, which I had left at a local shop on the intersection between Götgatan and Blekingegatan in Stockholm.

Friday, August 13, 2010

I was supposed to stay in Kumla until Saturday morning and then go directly to the Swedish Trade Union Confederation’s LO Castle building, where the seminar was going to be held. But the pressure leading up to the seminar, both from people who want to attend and journalists who wish to write about it, is so great that everything that needs to be looked after can’t be done remotely. I am needed in Stockholm and feel like I’ve had my fill of homophobic Christian Rights people who lack solidarity.

I contact Donald and receive confirmation that Julian Assange thinks sharing my apartment is totally fine. So, I meet Julian for the first time at the door to my apartment.

“I’ve been looking through your underwear drawer,” he says, holding up a bra. “I saw the size of this and thought, she’s someone I’d like to meet.”

He seems partly serious, and I don’t know how to respond. It’s quiet for a second. It feels uncomfortable. Then I laugh it off.

We decide to go out to eat at a small, local restaurant near my apartment. “They’re watching me,” Julian says.

“Hmm,” I reply.

“They’re watching me,” he repeats with a lowered voice.

Four floors down on the other side of the building, cars are parked on both sides of the street. Julian walks around to look in the windows but doesn’t see anyone inside. None of the cars have tinted windows. None of the cars looks suspicious. He looks for a little longer. I stand there watching him. It’s hard to decide whether he’s serious or kidding, but at any rate, he feels ready to proceed after a while, and we continue walking.

It’s a pleasant evening on Blekingegatan, the street Greta Garbo lived on as a child. We get Thai food and mineral water, and Julian monitors the flow on Twitter so intently that he doesn’t even hear the waitress when she tries to ask him if he wants more rice. He reads aloud from a British tabloid article about his hair and mentions with joy and pride that the paparazzi chased him in England. But here in Stockholm, no one seems to have recognized him yet, and those parked cars sit there, perfidiously empty of observers. It strikes me several times that he seems like a person who needs someone to take care of him.

It is fun to chat with him. He seems bright and friendly. We have many similar values and a structural analysis based on the same goal of human liberation. I don’t need to explain why I think equality is important or have all the arguments about the inherent value of a peaceful world. We agree with and build on each other’s views, as I do with my best friends, even though we have only spent a couple of hours with each other. We look at human rights issues in the same way, but feminism and equal rights for women seem to be an exception to this for him.

“But that’s a very strange inconsistency, Julian,” I say.

He laughs apologetically and responds, “The feminists caused the war in Afghanistan.”

I laugh. There is no reasonable way that the man who, literally speaking, epitomizes the helicopter perspective on global politics right now can be so stupid that he seriously believes women’s rights caused the most recent in a series of the great powers’ abuses against Afghanistan, merely because it fits his purposes to get Western opinion on his side. But with a smile, he insists that feminism and demands for gender equality bear responsibility for the war. I continue laughing and decide to believe he is joking. I don’t know how else to deal with him.

The waitress is still waiting to hear if he wants more rice. I take him by the shoulder and give him a little shake as if to try to wake him up, and he responds that yes, he would like more rice.

After dinner, we walk back to my place and continue our discussion of global politics and the next day’s seminar. I have a mattress under my bed, which I get out for him to sleep on.

I have made my own bed and set out sheets for Julian’s mattress, but it’s as if he does not understand that he should make it himself. He just looks neutrally from me to the sheets.

When I hand him a teacup, he suddenly caresses my hand with his thumb. I am a little surprised and think, oh, where did that come from? It was like a bolt out of the blue since we hadn’t flirted at all during the evening. I pretend not to notice it and go out into the kitchen, where I stand for a moment. The realization sinks in that Julian Assange wants to make out.

I think about Andreas’ acidic comment when he discovered that the WikiLeaks founder would stay in my apartment.

“Oh, so you’re going to score with Assange?”

“No,” I replied. “I’m not going be staying there.”

Andreas and I became a couple many years ago when I moved to Uppsala to study, and only six months later, we took a trip to Cuba together. At a market in Madrid, during a layover, we bought rings that cost seven euros and got engaged.

He had just started studying for his Ph.D. in data communications, and we called ourselves each other’s “orange halves” from the Spanish for soul mates. We fought all our political battles together, arranged big parties, had the same friends, and loved each other very intensely. We were convinced that the constant stress, which made him irritable and preoccupied, would disappear once he had finished his dreadful dissertation. And with that, all our problems as a couple would go away.

But nothing improved after he defended his dissertation. He began a management job for an organization and became even more stressed and distracted. We postponed our plans to have kids from as soon as we finished our studies to some unspecified time in the future. When I hugged him, he stood with his arms straight down until I asked him to hug me back. He accepted my love but gave me almost nothing in return. Despite this, we remained a couple; I couldn’t imagine anything else.

He needed an assistant, he said. He couldn’t keep up with all his administrative tasks, and his receipts were in utter chaos. I asked around among my friends for tips and found a woman who seemed great. She started working, and they got along well.

Six months later, we were sitting in his little studio apartment on Kungsholmen, and he handed me a letter. He sat across from me while I read it. He wrote that he couldn’t say what he wanted to express. My heart was pounding so loudly it was interfering with my thoughts, my pulse racing and throbbing in my temples because I had a feeling about what I was going to read. He had started a new relationship with the woman we had recruited together.

We continued to hold onto the tatters of our relationship for over a year. He wanted to cultivate his other relationship and hold onto me at the same time. And there I was, humiliated, off in one corner of the boxing ring of his life. He broke up with me several times, but he came back crying after each and said that this time, it would all be different. Despite all this, he continually settled on wanting me to accept his wishes for an “open relationship”.

It hurt so much, like being stabbed in the heart. Sometimes I haven’t been able to get out of bed. Whole nights have been spent in sleepless tears. But the most serious consequence of my relationship with Andreas may have been the destructive relationship I developed with myself.

After talking to a couple’s counselor, I finally ended the relationship, and I have officially been single since the spring, although we still see each other. Before and after I broke up with him, I dated many very fine men. Some I dumped brutally and immediately, and others I clung to or pushed away. Some I was downright mean to. And my heart has remained with Andreas the whole time.

One of the many ways I used to numb the pain and cope with the breakup was translating “7 Steps to Legal Revenge,”2 which I had found on a message board earlier in the year, into Swedish. I placed a link to it on my blog, and Andreas was hurt. He resented my even thinking about revenge at all.

After living in various sublet and sub-sublet apartments with short contracts and big water leaks, I finally bought my first little apartment all of my own on Tjurbergsgatan in Stockholm’s Södermalm neighborhood, and that’s where I’m living now. It is here I stand on the balcony, looking out over the inner courtyard and the windows of my 200 neighbors. I’m still not feeling great, but I’m on the mend. It might be a pretty fun thing—and no big deal—to “score with Julian Assange.”

A semi-famous Australian. A jealous ex-fiancé vaguely impressed by celebrities.

So why not? I think.

Everyone I have talked to about the seminar over the last few days seems to agree about how exciting it is that the WikiLeaks founder is staying at my place. A few days ago, a crowd of fans stood screaming as if at a rock concert when Julian spoke. Their screaming reinforced Julian’s image of a person considered so cool in certain circles that you yourself become cool simply by having a mask with his face on it in front of your own. If that’s what they think, then he must really be cool.

During my long on-again-off-again period with Andreas, my selection criteria for whom I’ll make out with has grown lax. It’s been fun, too, and has worked out well many times.

So, you’re going to score with Julian Assange, Andreas says again in my head.

Yeah, maybe, I think.

Then I walk back into the room and over to Julian, where we make out a little and chat. He falls asleep in his clothes on my short, uncomfortable sofa. He’s completely exhausted, and I think it’s cute that he can sleep just like that. I take a picture with my phone. The great Assange sleeping like a kid on my little sofa, I think, and upload that restful prelude to tomorrow’s seminar onto Facebook. I instantly receive many likes and impressed comments in my feed from relatives and childhood friends as well as coworkers and even a gender studies researcher.

“You should be president or something,” the researcher writes.

It’s kind of nice that he fell asleep, and that we decided not to make out anymore. I change into my nightgown, brush my teeth, and am just about to go to bed. But when I turn off the overhead light, Julian wakes up. He strokes the outside of my thigh, stands up, kisses me, and pulls up my nightgown. I’m not willing and don’t like it, so I try to pull the nightgown down instead. He tugs several times, harder and harder. The seams start creaking as though they’ll tear. He starts pulling my panties off, too. Then, to keep the clothes from ripping, I let him take everything off. I don’t want to spoil the mood.

It feels bad. It’s going too fast. It feels like I started something I shouldn’t and can’t stop it. The most unpleasant thing of all is that I notice the change in the way he’s treating me. He stops chatting with me. He stops listening to my body language and what I’m saying. I no longer feel like the political and intellectual equal I was just moments ago. It’s as if he’s swapped out my whole raison d’être. I get a very strong sense that he thinks I owe him something he has already paid for. It’s as though since I agreed to A, I have therefore renounced my right to stop B.

If I were permitted complete freedom to choose, I would cut this short and go to bed now. But I don’t feel free. I feel I’m facing a clear demand to continue. It feels bad, but not bad enough to make a fuss, not bad enough to risk anything worse.

We lie on the bed, him on top and me underneath. It’s pleasant for a while.

We roll around, and when he takes off his pants, I notice a distinct smell—sperm. Evidently, he hasn’t showered off some old bodily fluids. From there, my discomfort escalates. He holds my arms over my head and presses his shoulder hard against my throat. I’m forced to gather all my strength to press my chin toward my chest to get air and make sure my voice box isn’t injured. I try to move and twist around, but he pushes his shoulder so hard into my throat that my silver necklace bites into my skin.

He's holding my arms at the wrists, his chest lies heavily over mine, and he’s using one knee to try and push mine apart. I can’t concentrate on anything other than getting air against the pressure on my throat, making me passive. I think that is his intention.

With my arms pinned over my head and my nightgown having been torn off, I understand very well what’s expected of me and what I’ve agreed to by not speaking up, not articulating the words, and not using the feminist self-defense I had learned. Because while I want to stop, I don’t want to be weird or difficult. I don’t want to dramatize the situation or exaggerate the fact that I no longer feel like it.

Men usually pick up on these kinds of things, anyway. They understand if I don’t want to and will lie down; I’ll get a hug, and we’ll go to sleep. Maybe we’ll pick up where we left off another day when it feels like more fun. That’s what my experiences with these types of situations have looked like. Julian doesn’t react that way at all. It’s more like he’s demanding his right and demanding I should continue. Oddly enough, inside, I feel the same thing he is signaling, that I’ve promised him something and have set out on a path leading in this direction. I’ve bought the tickets, and now it’s time to ride.

Even though I’d rather stop, I accept continuing but on one condition, which is absolute—protection. For a long time, Julian tries wordlessly to negotiate his way out of this.

He tries to hold onto me by force so he can proceed without a condom, and I resist, trying to shift my lower body away. Julian doesn’t make the least effort to let go or ask what I want. He keeps pressing.

When I move, he moves after me; when I repeatedly pinch my legs together, and he stops me as I reach for the nightstand, it’s clear I don’t count. It’s like a wrestling match without an audience or referee where I’m at a total disadvantage. To him, I’m probably not even there anymore. It is only my body—my forcibly undressed body—that is there. Repressed sobs build behind the lump in my throat. I feel on the verge of tears and completely powerless.

I pull as much as I can to get my arms free and curl into a fetal position beneath him. This way, I succeed in locking my legs to the side so that he can’t push them apart.

This is when I scream. Not literally, but when I realize I’m not going to be able to win with physical strength, I do something that feels just like screaming. I break the silence.

“What are you doing?” I say.

“What are YOU doing,” he snaps angrily as if accusing me.

“Why are you holding me down? I want to use a condom,” I tell him. He releases me and lets me move.

According to the “rules” for what’s considered to be a “real assault,” I shouldn’t compromise here. I should say no. I should say no, no, no. I should say that word, the only thing that counts. I should scream so loudly the neighbors can testify. I should try to get up and run out of the apartment. I should, in other words, humiliate myself in front of my neighbors and be held responsible for my mistake of letting it go this far. I should leave him with his rage and horniness—if he’ll even let me leave the room—run out, call the police, and ask them to arrest him. Or I should take the chance that a “no” gets him to let go of me, then pack his bag and throw him out here and now.

But the coldness in his eyes, our shared knowledge that he’s stronger than me, my experience of his completely ignoring what I want, and my being convinced he’s planning to have sex with me no matter what I say makes me assess the situation differently to how I will assess it later during rational reconstructions of the event. What settles it, maybe more than anything else, is the thought I should not make a scene. The feeling is driven by the primaevally strong norm to not exaggerate.

If I say the word “no” now, it will very likely be effective. A no is potentially as definitive as kicking him between the legs and screaming for the neighbors. That is precisely why I do not say it. It would be an overreaction; surely, it will be better now. I see myself as a reasonable person, not a drama queen.

So, I give him the condom and wait for him to put it on. But he doesn’t do it. He holds the condom in his hand and tries to proceed without it. I think, He has to give in now anyway; it’s impossible to misunderstand what I want. It’s clear enough to give someone a condom and sit and wait without it needing anything to be said. Although a small act of resistance, I still think it’s too much. I remind him.

Finally, he puts it on, and I end up underneath him again. He’s not holding my arms anymore but instead lying with his full weight on my chest. He enters me and presses down so hard against my neck that I feel like I’m suffocating. I’m still trapped beneath him but struggle so I can get my chin between us and push him up a little bit, away from my throat. My struggle to find ways out continues, but less intensely. I try to gain control of the situation and cool it down a little, to resist, close my eyes, and convince myself that it’s OK or could be OK. One strategy I try is attempting to enjoy it.

Maybe that’s what allows me to pull free. He releases the pressure from my chest and neck, and I can finally get some proper air and take a deep breath. He gives me permission to move around so that I’m on top and, for a second, I have a sense of control.

Again and again, though, he enforces that he makes the decisions and that he is stronger than me. He does this by holding onto me a little too long or grabbing parts of my body roughly. He doesn’t use force; he indicates it. All possible compromises seem to be based on my acceptance and continuance. If I make a fuss, I think, then there probably won’t be any compromise. That’s how I understand it. So, I try to avoid making too much fuss.

Julian has his shirt on. It seemed important to him that I should be naked as quickly as possible but that he should wear as much clothing as he could. That difference—me naked, he dressed—makes me think he doesn’t consider it worth undressing. There’s no trace of tenderness, no desire for more bodily contact than necessary.

I want to take off his shirt, not because I want more bodily contact, but to show I’m an active participant, that I’m not just an object he can use. Julian doesn’t want to take it off. This is foggy, but I think I get it off him in the end.

Being active, trying to take control, and even succeeding in gaining control, diminishes my degradation. Maybe I’m legitimizing his behavior, but in this situation, it’s a way of saving myself. I even succeed in having a micro-orgasm, which makes us a little more equal; it’s more reciprocal and less of an assault and power display.

Then he’s pressing down on my neck again. I feel like I’m suffocating, and his lack of care and total self-focus frustrates me.

After a little while, he firmly grips my hands again, but only with one, and suddenly pulls out. Simultaneously, I hear a clear snapping sound, like a balloon popping, and I’m convinced he has taken off the condom, considering his resistance to wearing one. I manage to get one hand free and feel to check. No, it’s still on.

That I was able to get him to use a condom and keep it on is an enormous relief. The feeling I have can be described as a worm that has escaped from a hook. I push my anxiety about the sound aside, and I let him continue, even though my body is still trapped.

After maybe fifteen minutes, he’s done.

He does something odd after his orgasm; he attempts to make me come. The gesture is confusing after the last thirty minutes of cold indifference.

Again and again, I have wondered how to describe the assault and my own actions. I know many people expect a black-or-white truth. To accept what happened and call it an assault, people expect a monster to have violated an angel. But how do I avoid pleasing them? How do I avoid the stereotype of the monster to get closer to the leaden, gray truth? How do I avoid making myself look better than I am, and how do I deal with the inconsistencies in my actions? In real assault stories, there’s almost never a monster violating an angel but rather one human being violating another.

Reviews of this book from Julian’s network of supporters will upgrade an orgasm or two into watertight evidence that no assault took place. All of the victim’s human inconsistencies become ammunition for those who want to prove a sex offender is innocent. Victims of crime know this. But the truth is often right there, in what is perhaps more human than inconsistent, in the gray areas.

There’s a big wet spot on the bed. “What’s this?” I ask.

How could his semen have gotten into me and then run out? “You were very wet,” he replies.

“No, Julian. I wasn’t,” I say.

Because I really wasn’t. It’s obvious that it’s from him; that snapping sound was the condom breaking. This is pretty important since a broken condom does not serve any purpose against disease or unwanted pregnancy. But he says nothing about the condom breaking, pretending nothing happened. His right thumbnail is long and sharp, and his lie, you were wet, puts a heavy lid on my question.

We say no more about it.

I don’t know the word yet, but what Julian is doing is gaslighting me, a form of manipulation in which information is distorted, misrepresented, or omitted, or where information is presented with the aim of making the victim doubt their own memories, their own experience of reality, and their own mental health. It’s appallingly effective.

He says something that both he and I know isn’t true at all, but through a sort of mutual theater in which we both pretend we believe the illusion; reality then starts to blend with his conscious—and to me, obvious—lie. After a little while, I’m unsure where the line is between truth and lie.

I find my broken necklace next to me on the bed and set it on the nightstand. Then, I go to sleep.

Saturday, August 14, 2010

When I wake up in the morning, I find the empty condom on the floor and throw it in the trash.

I write a short note to Julian.

Hi Julian, it wasn’t pleasant at all for me to sleep with you, so you and I won’t be doing that again, but I want to give you a checklist with a few suggestions for the sake of your future partners:

—Don’t break people’s necklaces.

—Don’t press your shoulder against their throats so that they almost suffocate.

—Don’t ejaculate inside people if they don’t want that.

—Shower.

I set the note in a folder he uses to gather notes from fans, records of various scholarships and donations he’s received, and groupies’ phone numbers. If he sits down and checks it, he’ll find the note from me too. I feel like I’ve faced the conflict but also escaped it by defending myself this way.

When Julian wakes up, we both act as if nothing has happened. His WikiLeaks coworker Johannes, whom I arranged Julian’s travel with, is going to pick him up in a taxi. Julian thinks I should go with them, but I leave alone and take the metro.

We set things up and try to connect Julian’s computer to the projector in the LO Castle building. We need an adapter, so when Maria, the volunteer, arrives, we immediately send her to buy the necessary cord.

Journalists pour in, take their seats, and Julian gives his presentation about WikiLeaks and the importance of truth and transparency in putting a stop to war crimes. I have a long list of journalists in line for interviews afterward. The seminar resembles a press conference rather than a public lecture.

One of the few non-journalists at the seminar is a young woman representing Sweden’s Pirate Party.

“Can I have your autograph?” she says to Julian when she manages to push her way to the front after the presentation.

“No,” he says. “I don’t give autographs as a matter of principle.” “But you don’t understand,” she replies. “You’re my Brad Pitt!” They talk for a while, but a moment later, she’s gone from the hall.

“Damn,” Julian says to me. “I should have gotten her phone number.”

The first interviews take place indoors with public television, radio, and evening news programs. Afterward, we need to leave the hall and move outside into the sun. I keep track of the time on a bench by a statue of August Palm. The journalists ask questions, and Julian answers patiently.

For some reason, he wants to sit right in the broiling sun. It’s roasting, and the heat makes his TV makeup run. Sweat mixed with makeup drips down onto his clothes, and his shirt grows wet, as each newspaper, magazine, and channel get its promised minutes.

While Julian is busy with interviews, I chat with Maria and the journalists who are waiting.

“Look at his finger,” I say to Maria. “Do you see that engagement ring he’s spinning?” Julian found my ring from my broken engagement with Andreas at my place and, without asking, has brought it along and put it on. He makes a show of twisting the ring around in front of the journalists. I say that he probably wants to start some sort of speculation. I smile as I speak, but it does not feel OK at all.

The papers Arbetaren (The Worker) and Computer Sweden are the last two to get to ask questions.

“I should have gotten her number,” he says again as the stream of questions subsides. He’s referring to the young Pirate Party representative. Then, he repeats her declaration that he has entered the Brad Pitt league of sexiness.

I have never met Brad and don’t want to contribute to creating new myths; however, I find it extremely difficult to see the similarities between him and the man sitting here with his unbrushed teeth and goopy TV makeup pretending to be engaged. I ask for my ring back and get it, feeling a little unwell in the heat.

It's afternoon, and everyone is hungry. My organization invites its staff and participants to lunch at Bistro Bohème on Drottninggatan. Maria is invited by our chairman Peter as a thank you for her assistance in getting the cord; she ends up sitting next to Julian at the table. They flirt. He feeds her crisp bread, and they seem to like each other.

“What are you doing this afternoon, Julian?” I ask.

“I don’t really know,” he replies.

“I can take you to a museum,” Maria says. They leave together after lunch.

Nice for him, I think. It feels good not to need to be responsible for him. Instead, I have time to arrange a crayfish party at Donald’s request. He reports that Julian has heard of this Swedish August phenomenon and is eager to try it.

I search through my event invitations and ask around. When I don’t find a pre-planned crayfish party he can attend, I instead buy crayfish and invite a few people over to my place for a potluck party.

Julian has slept in my apartment for two nights now, which is what we agreed on from the beginning, but he still has not moved out. I don’t want him here. During the day, I get in touch with a friend in the Pirate Party who finds a couple willing to host him. The couple can’t or don’t want to come to the party, but they live nearby and promise to pick Julian up later.

On my way home, I spot a person I recognize from the seminar at the subway station and say hi. We start talking and I invite him to the crayfish party. He doesn’t have time to come tonight but says he can help me get some Schnapps for the party. He’s cute in an innocent way and smiles the whole time. I feel like there’s an amorous look in his eyes when he looks at me. I go with him to his apartment to get the Schnapps, and he says we should get together sometime. Absolutely, I say, that would be fun!

One of my closest friends, Petra, comes over to my place to help. We met for the first time in the Uppsala student union, where she, just like me, was working on gender equality issues. She’s currently working on a Ph.D. in statistics and has represented Sweden in international chess competitions. I usually describe Petra as the only genius I know. She’s also an extremely sharp feminist analyst.

“It was awful. Actually, the worst lay ever,” I say.

My own voice sounds skeptical and bewildered as I tell her what happened the previous night. I realize that the snapping sound wasn’t the condom breaking but rather being broken. Even though he only used one hand, he broke it quickly and skillfully, as if he had done it many times before.

“He broke the condom on purpose?” I say as if I don’t believe it myself.

“What? Super weird,” Petra says. “Why would he do that?”

I have no answer to that. Even though it happened and I heard the sound when it broke—a second before I felt him enter me—he managed to make me believe it didn’t happen. If there’s no answer to why someone would do that, then it’s illogical to think it happened. I’m forced to choose between logic and fact. The story fits together better if I choose to ignore reality. It’s a paradox I cannot resolve.

Saturday, August 14, 2010, Evening

Evening arrives. It’s a beautiful and warm Swedish late summer evening. My friends, Julian’s friends, and I have drinks in the kitchen. Julian doesn’t show up at seven, as we had said. Nor at eight. He doesn’t come until just after nine. There are crayfish left, and the party continues in the lovely outdoor common space owned by HSB, the cooperative housing association.

Julian is a terrific person in many ways. Incredibly quick-thinking, funny, with a knack for constantly coming up with unexpected angles. The party attendees volley banter back and forth like table tennis balls over a net, and we laugh a lot. It’s the type of environment where I’m at my happiest.

The Julian who attends the crayfish party is a completely different one than the Julian who humiliated and used me the night before—I decide not to see the horrible Julian anymore, just the nice one. And it appears as though I can make that choice. In the conversation tonight, I am once again an equal, someone worth listening and responding to.

I write on Twitter about how wonderful it is to hang out with some of the smartest and most fun people—people like Kajsa and Johannes, whom I talk to most.

How warm the weather is and how light the evening is. How privileged I am.