25,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

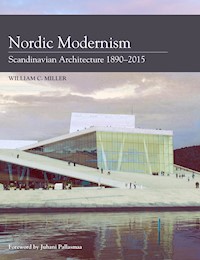

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Modernism was instrumental in the development of twentieth and twenty-first century Scandinavian architecture, for it captured a progressive, urbane character that was inextricably associated with, and embraced the social programmes of the Nordic welfare states. Recognized internationally for its sensitivity and responsiveness to place and locale, and its thoughtful use of materials and refined detailing, Nordic architecture continues to evolve and explore its modernist roots. This new book covers the romantic and classical architectural foundations of Nordic modernism; the development of Nordic Functionalism; the maturing and expansion of Nordic modern architecture in the post-war period; international influences on Scandinavian modernism at the end of the twentieth century and finally, the global and local currents found in contemporary Nordic architecture. Superbly illustrated with 100 colour images.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

First published in 2016 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

© William C. Miller 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 237 3

To Beverly and her valiant struggle with Alzheimer’s disease

Contents

Foreword by Juhani Pallasmaa

Preface

Chapter 1 The North: Life on the Edge of the World

Chapter 2 The Journey to Modernism: A Romantic and Classical Voyage

Chapter 3 Modernism Arrives in Scandinavia: Nordic Functionalism

Chapter 4 Place and Tradition Modify Functionalism: A Critique

Chapter 5 Post-War Exploration: A Maturing and Expanding Modernism (1945–70)

Chapter 6 No Longer Your Parents’ Modernism: International Influences and Nordic Identity (1970–2000)

Chapter 7 The Global and the Local: Creative Currents in Nordic Architecture

Endnotes

Bibliography

Index

Foreword: Myths and Realities of the North

The Image of the North

THE NORTH IS SIMULTANEOUSLY A MYTHIcal and concrete notion, mythical in a mental, symbolic and historical perspective and concrete in terms of being one of the most stable and balanced corners of the world and an ideal of well-functioning modern democracies. The North has traditionally been seen as the remotest region of Europe with a rather disadvantageous climate. However, the current warming of the global climate and the eventual opening of new northern shipping routes, as well as the newly found natural resources in the Arctic Ocean, are potentially changing the peripheral location of the area. The notion of ‘The Northern Dimension’ reflects this new attention and has already become part of today’s political and economic terminology. The current environmental and cultural developments may well alter the dialectics of centre and periphery. In today’s world of forceful technologies, we tend to forget the fact that it is due to natural conditions, the Gulf Stream, that human culture at the level of the Nordic countries, located largely north of the 60th latitude, has been possible in the first place.

As a mythical mental image, the North is not a place, but rather an orientation, an atmosphere and a state of mind. Historically, ‘the North’ has referred to the unknown. Virgil, the Roman poet of the Augustan era, used the term Ultima Thule, the ultimate north, as a symbolic reference to an unknown far-off place, a non-place and even an unattainable goal. This mythical echo still reverberates in the dreams and thoughts of Southern cultures. The Southern cultures have traditionally dreamt of the North, whereas the Nordic people and artists have longed for the South, particularly the Mediterranean world. Characteristically, due to the idealized imagery of Southern deciduous forests and cultural landscapes, Finnish artists did not paint their dominant coniferous or mixed forest before the mid-nineteenth century. Something of the ageless mythical feeling of the North still exists even in the minds of today’s Swedes, Norwegians and Finns, whose countries extend well beyond the Polar Circle; northern Lapland and the Arctic Ocean continue to project an air of danger, mystique and the unknown.

The concepts of the Nordic countries as well as of Nordic architecture are products of the modern era, as they did not exist in a wider international consciousness before the late nineteenth century. The monarchies of Sweden, Denmark and Norway have long and varying histories, whereas the idea of national independence emerged in Finland only towards the end of the nineteenth century and was decisively promoted and formulated by the arts. Alvar Aalto makes the point that only through the Finnish Pavilion at the Paris World Fair in 1900 did Finnish culture enter an international consciousness and dialogue.

For the first time, Finland appeared on the continent with tangible materialized forms as a source of culture that might influence others, rather than simply being on the receiving end … It is difficult for a small country to make its psyche understood in a global context, the more so if it has a language that is, and will remain, alien to the otherwise close-knit family of European languages … We need a language that has no need to be translated. One might say that the existence of a new language was gradually revealed in Paris in the spring of the year 1900.1

Here Aalto refers to the material language of architecture and the non-verbal language of music. This view of the significance of Eliel Saarinen’s Finnish Pavilion applies to Nordic architecture altogether; since the late nineteenth century, the Nordic countries have had masterful individual architects who have become part of the world history of this art form. Not to underestimate the contributions of Nordic writers, artists, composers and scientists for the Nordic identity, I venture to argue that it is through the modern democratic societies and general cultural achievements in the material arts, such as architecture, that the Nordic countries are known in the larger world today.

The Interplay of the Material and the Mental

The Nordic countries2 are often seen as a unity and indeed, the cultures, lifestyles, values and artistic expressions of the four countries (Iceland, the fifth Nordic country, is not included in this book) are similar and their long intertwined histories have tied these nations together in a multitude of ways. But the differences are equally noticeable. The differences are distinct in the geographies, landscapes, human temperaments and cultural habits, as well as artistic sensibilities. Generally we are not very sensitive to understanding differences in the material world, but the differences are as clear as between cultural behaviours and languages. We habitually underestimate interactions of environments and culture, settings of life and human character. Yet our environments of life and our minds constitute an indivisible continuum. As the visionary American anthropologist Edward T. Hall argues:

The most pervasive and important assumption, a cornerstone in the edifice of Western thought, is one that lies hidden from our consciousness and has to do with a person’s relationship to his or her environment, Quite simply, the Western view is that human processes, particularly behaviours, are independent of environmental controls and influence … The environment provides a setting which elicits standard behaviours according to binding but as yet unverbalized rules which are more compelling and more uniform than such individual variable as personality … Far from being passive, environment actually enters into a transaction with humans.3

We still underestimate the interactions of environments and culture, settings of life and human character and do not see or acknowledge their interdependencies. Yet, as the American literary scholar Robert Pogue Harrison suggests poetically: ‘In the fusion of place and soul, the soul is as much a container of place as place is a container of soul; both are susceptible to the same forces of destruction ….’4 The common view that architecture is an individual artistic expression of the architect is simply false, as architecture is necessarily a consequence of countless historical, geographic, social, cultural and economic factors. The essence of the artistic expression is hardly purely individualistic either. ‘We come to see not the work of art, but the world according to the work’, Maurice Merleau-Ponty argues wisely, and this view certainly applies to architecture, too.5

Towards Modernity

Due to their 600 years of shared political history and rather similar geographic conditions, Sweden and Finland share more similarities, perhaps, than the other Nordic countries, although they also share their complexly intertwined histories. Even language conditions our ways of perceiving the world and dealing with it conceptually, intellectually and emotionally. Consequently, it is reasonable to argue that our mother tongue is our first domicile. As a Ural-Altaic language, Finnish is fundamentally different from the other Nordic languages, which belong to the Indo-European language group. The fact that Finland has a 6 per cent minority population, mainly located on the south and west coasts, who speak Swedish, further complicates the interplay of similarities and differences. In any case, the differences are equally clear as the similarities. Due to her location, Denmark has naturally been more connected with continental European cultures and its general mentality is more urban and perhaps more sociable and open-minded. Historically, the Norwegians have been somewhat isolated due to their rugged mountainous geography and deep fjords and this condition has been reflected in their character, as well as their cultural products.

The art of architecture has developed firmly in the Nordic world without major conflicts, all the way from the late nineteenth century until today. Even the peasant and small town urban vernacular traditions were assimilated in the emerging modernity. The Nordic Classicism of the 1920s, sometimes called ‘Light Classicism’ because of its casual and good-humoured tone, drew its inspiration from the architettura minore, the urban vernacular of northern Italy, and blended it with the indigenous Northern building traditions. This restrained but elegant classical language paved the way for modernity; most of the leading exponents of Nordic Classicism turned into modernists within a year or two. The new architecture, which emerged in the end of the 1920s and was usually called ‘Functionalism’ (the terms ‘Rationalism’, ‘New Realism’ and ‘New Objectivity’ were also used), soon adopted softer regional and traditional features and turned into the unquestioned and unchallenged architectural expression of the progressive modern Nordic societies. Instead of orthodox stylistic attitudes, Nordic architecture in general has had an assimilative character. It is exceptional on a global scale in that modernity became the culturally accepted style early on and historicist or revisionist aspirations have not re-emerged since. Even the postmodern and deconstructivist trends of the 1980s had only a minor influence in the North. The modernist formal language, both in architecture and the design of everyday objects, became a constitutive ingredient in the identities of modern Nordic societies. The movement of ‘Vakrare vardagsvara’6 (more beautiful everyday objects) arose in Sweden in the 1920s and turned into an unchallenged cultural condition in all the Nordic countries.

Architecture and Nordic Identities

The socio-economic and political history of Sweden and the ideals of social justice and equality have been reflected especially in Swedish architecture. During the entire era of modernity, Swedish architecture, and especially housing, has been guided by a strong social and sociological orientation, as well as the ideals of solidarity and the modern state as ‘the People’s Home’. Artistically, this social orientation of Swedish architecture has sometimes seemed to turn into an architectural weakness and lack of artistic autonomy, because of a patronizing attitude. However, in retrospect, it is evident that the acceptance of the requirements for domesticity has been a form of responsible social empathy as opposed to an architect-centred formalist aestheticization. The domestic bliss depicted in the delightful paintings of Carl Larsson reveals this mental inclination towards cosiness and domestic bliss, which can be felt in much of Swedish architecture even today.

Danish architecture is traditionally a product of a sense of urbanity and higher social compactness. The flat, cultivated landscape has also been imprinted in the Danish character, settlements and architecture. The intimate scale, refined materiality and detailing, as well as craft skills, speak of established human relationships, urban professionalism and lively traditions of trade. Danish architecture also reflects a tradition of human forbearance and enjoyment of life in comparison with the sense of seriousness of Finnish and Norwegian buildings. A distinct lightness and elegance have characterized the Danish architectural tradition.

In accordance with the relative isolation and harshness of life, Finnish architecture has always reflected individuality, but even more importantly, the prevailing forest condition. Certain features of Finnish architecture, such as its sense of tactility, the frequency of irregular rhythms and appreciation of natural materials, evidently echo the forest condition, which nowadays is more often a mental and experiential attitude than an actual condition. We could here speak of a ‘forest mentality’ as the guiding reference for spaces and forms. For a Finn, since the ancient times, forest has signified safety, protection and comfort, as opposed to Central European cultures for which forest usually implies threat and discomfort. In the olden days Finnish life meant living in communion with the forest. Forest was the peasants’ entire world; it was there that they cleared land for farming and caught game and from the forest they took the raw materials for their buildings and implements. The forest was also the sphere of the imagination, peopled by characters of fairytale, fable, myth and superstition. The forest was the subconscious realm of the mind, in which feelings of safety and comfort, as well as fear and danger, lay. ‘We Northerners, especially the Finns, are very prone to “forest dreaming”, for which we have had ample opportunities up to now’, even Alvar Aalto, the cosmopolitan, once said.7 In Finnish culture, a modesty or restraint, ‘the noble poverty’ of peasant life, can still be detected as a common value.

Until recently, Norwegian architecture has reflected a strong consciousness of tradition and the rugged mountainous landscape and sense of isolation can be detected in the character of Norwegian architecture. Seafaring traditions have likewise had their impact on Norwegian life, architecture and crafts. During the past decades, however, architecture has changed in Norway, perhaps faster and by a greater amount in its general character than in the neighbouring countries, towards the dominant international architectural language. As a consequence, the traditional ground cannot be identified in today’s Norwegian buildings as clearly as just a couple of decades ago. The recent national wealth from oil resources has dramatically changed the economic conditions of the country, but the newly acquired wealth hardly shows in daily life, which speaks of a maturity of the collective values.

The Societal Role of Architecture

Architecture is undoubtedly the most collective of art forms and it takes place at the intersection of tradition and innovation, individuality and collectivity, convention and uniqueness. It is also bound to balance between aspirations for differentiation and assimilation and the Nordic temperament has rarely wished to stand out from the group or context. As a consequence of their gradual evolution, Nordic architectures have become rooted in these social realities more strongly than in other parts of the world and they have had a determined societal mission. In post-war Finland, for instance, architecture decidedly aspired to raise the self-consciousness and esteem of the people, shattered by the disasters of the war. Rapid reconstruction and high aesthetic quality became a form of mental recovery and a source of pride. The fact that in 1998 Finland’s Council of State approved ‘The Finnish Architectural Policy’ – presumably the first governmental architecture policy in the world – underlines the special role that the art of building has been given in Finnish society. In the entire North, architecture has been used as a means of societal reaffirmation and unification rather than of differentiation and polarization. In the early 1950s, Alvar Aalto saw the task of public buildings as setting a model of architectural quality for the construction of settings even for daily life and work.

The emerging ‘class-free’ society is still more vulnerable than the bourgeois society generated by the French Revolution, for it includes larger numbers of people, whose physical well-being, sense of citizenship and cultural awareness will depend critically on the correct ordering of the institutions and areas serving the public.8

The cultural, ethnic and social homogeneity of the Nordic nations, as well as their long period of undisrupted social and economic development, have reinforced this attitude of solidarity. However, the abrupt increase of differences in income levels in today’s neo-liberal consumer society threatens this traditional sense of societal coherence, togetherness and equality as well as the Nordic ideal of the welfare state. The current unrest in Europe and the largely uncontrolled mass immigration of refugees poses an unexpected challenge for the Nordic social balance, but also for individual judgement and sense of responsibility.

Light and Silence

We tend to think of regions and places primarily in terms of geography, landscape and material settings, but often the most important single quality that creates the sense of a unique place is the ambience of light. In his book Nightlands: Nordic Building, the Norwegian architectural historian and theorist Christian Norberg-Schulz emphasizes the power of the natural illumination in the North: ‘It is precisely light that defines the Nordic worlds and it fuses all things with mood … In the North we occupy a world of moods, of shifting nuances of never-resting forces, even when light is withdrawn and filtered through an overcast sky.’9 No doubt the character and dynamics of light are tangible; the night-less summer as well as the day-less winter, when light seems to radiate from below, as snow picks up the slightest source of light from the firmament and reflects it back, are special conditions of Northern illumination. Even sunrises and sunsets, as well as cloud formations, rain and snowfall, have atmospheres of their own that are distinctly different from any other location on earth. As a consequence of this ever-changing dynamic of light, Nordic architecture is more sensitive to light than architecture elsewhere. Architects of the Northern countries, more than in other regions of the world, design special light fixtures for their buildings in order to articulate even artificial light. Light is a precious gift for the dweller of the North and it is naturally celebrated in life and architecture. Although historical buildings often contain beautiful arrangements of light too, the understanding of the expressive potential of illumination seems to be a modern sensibility.

Twenty years ago I had the opportunity of seeing an exhibition of Nordic painting of the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries titled ‘The Northern Light’ at the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid. The paintings were hung thematically, irrespective of their country of origin and I was struck by the uniformity of feeling that the paintings were steeped in; scenes of lonely human figures in landscapes, dim dusk and twilight, a sensation of humility and silence and a distinct sense of melancholy. Indeed, the sense of Nordic melancholia was unexpected and striking. This unified nature of Nordic sensibility for illumination was revealed by the sharpness of the Southern light as much as the silence was accentuated by the urban bustle of the Spanish streets. I had not understood the unity of the Nordic condition quite so clearly before this simultaneous encounter of the Northern and Southern light. No doubt we tend to become blind to our own environment and everyday reality and we recognize them only when valorized by opposite conditions.

The North and the Consumerist World

During the past two or three decades, the Nordic countries have regrettably lost some of their unique and exemplary qualities as architecture increasingly reflects global values and fashions. At the same time, the strong subconscious connections between the built surroundings and patterns of life have also weakened. During the past three decades, Spain has become the most inspired and inspiring country in the field of architecture. Why that should be the case is not easy to explain. Perhaps the liberation from a long period of political suppression has released creative energies, whereas the Nordic countries have taken their societies and economic and cultural achievements too much for granted or as self-evident conditions. Creativity never arises from self-satisfaction and complacency. Consumerist habits and values have also weakened the idealist quality of Nordic modernity, as the tendency for societal idealization has often been replaced by individualistic aestheticization. The Nordic countries may be losing some of their identity and character through accepting processes of internationalization and globalization too uncritically. On the other hand, the general values in architectural judgement around the world have favoured a spectacular and visual imagery and Nordic architecture has not offered many examples to be celebrated by this misguided orientation. So the sensationalist ambience of the international architectural publications may somewhat explain the relative absence of the Nordic countries from the international scene of celebrated architecture.

I do not believe that architects today should try to develop deliberately regionalist features using local vernacular or historical examples or thematized aspects of landscape and culture. Architecture is too deeply rooted in the collective mental ground and cultural past to be turned into consciously thematized or manipulated strategies. Simply knowing and respecting one’s own identity and cultural heritage sensitizes one for the subtleties that support the experience of a specific place, culture and identity. Nordic post-war architecture projected an optimistic and modern egalitarian attitude, but echoed simultaneously a traditional sense of materiality, craft and scale and, especially, a touching humility and compassion. The most beautiful quality of Nordic tradition even today can well be its modesty and sense of realism and appropriateness, combined with a subtle aesthetic sensibility. ‘Realism usually provides the strongest stimulus to my imagination’, Alvar Aalto confessed.10

Juhani Pallasmaa,Architect SAFA, Hon. FAIA, Int. FRIBAProfessor Emeritus

Preface

ARCHITECTURE IS A MANIFESTATION OF human culture and society realized in a particular place or location. The importance of place or location cannot be underestimated as it directly impacts building, for nature plays her inextricable role in the making of human habitats. While society determines and defines our building types and their purpose and meaning – church, school, town hall or airport – the particular character of the natural world a building inhabits directly impacts its making. For nature determines experiential qualities like dark versus light, hot versus cold, rough versus smooth and humid versus arid, and natural phenomena like clouds and rain, forests, deserts, oceans and dust storms. At the same time nature provides the resources needed for human construction: wood, stone, metals, turf and soils and water. As such, the very different places we have chosen to live provide unique sets of resources to use in realizing architecture. It is humankind’s capacity to produce meaningful, expressive spaces and places from those resources, thus releasing our cultural and creative energies.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!