45,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

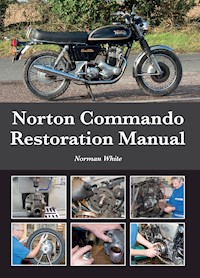

The Norton Commando is a motorcycle with an ohv pre-unit parallel-twin engine, produced by the Norton Motorcycle Company from 1967 until 1977. With over 700 colour photographs, this book provides step-by-step guides to restoring every component of this classic bike. Topics covered include how to find a worthy restoration project; setting up a workshop with key tools and equipment; dismantling the motorcycle to restore the chassis, engine cradle and swing arm; restoring the isolastic suspension, forks and steering; tackling the engine, transmission, carburettors, electrics, ignition and instruments and, finally, overhauling wheels and brakes, and replacing tyres. There is also a chapter on the assembly of a restored 'Five Times Machine of the Year' motorcycle.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Norton Commando Restoration Manual

Norton Commando Restoration Manual

Norman White

First published in 2020 by The Crowood Press Ltd Ramsbury, Marlborough Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2020

© Norman White 2020

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 760 6

contents

dedication and acknowledgements

1

introduction

2

finding a worthy restoration project

3

workshop tools and equipment

4

dismantling the motorcycle

5

the frame

6

the sub-assembly

7

front forks, steering and rear suspension

8

the engine

9

transmission

10

carburettors, fuel and emissions

11

electrics and ignition

12

lubrication

13

wheels, brakes and tyres

14

instruments

15

assembly of the restored motorcycle

16

maintenance and upgrades

17

the ultimate restoration

recommended retailers

index

dedication

John Mclaren 1935–2017 This book is dedicated to John Mclaren, the quiet and unassuming genius in the background who played such a major role in the history of the Norton Commando. He is the finest craftsman I have had the privilege and pleasure to have known and worked alongside.

acknowledgements

This is my first book, and indeed by far the longest piece of script I have ever produced. The chairman of Norton Villiers, Dennis Poore, once praised me for the detail I would include in my test reports when I was a development test rider in the early 1970s. I sincerely hope I have retained some of my ability to describe how the Norton Commando functions and deserves its reputation as a five times ‘Machine of the Year’ winner 1968–72. It truly is a marvellous motorcycle.

I would like to take the opportunity to thank all of those who have helped me to complete this book, including some of my former colleagues at Norton Villiers, customers and some people whom I have never met:

Anders ‘Norton’ Larsson

Andover Norton and their merry men Joachim Seifert, Ashley Cutler, Brian Gower and Simon Amos

Bruce and Billy Horne

Ernie Bransden

Ferret

John Favill

John Nutting

Mike Jackson

Mick Ofield

Owslebury crankshaft services, John Gray and Mike Bettridge

Peter Williams

Phil Baker

Richard Negus

Rob Rowley

RS Bike Paint’s Phil Allen

SRM Engineering

Trestan Finishers

A special thanks to Mike Dance for his time and patience taking most of the superb photographs, and Phil Edwards for spending so much time sending me photos and obscure historical facts and details. Last but not least, thanks go to my wife, Marsha, who has suffered most by my computer ignorance, guiding me through the keys and applications I had no idea existed.

The 750cc Norton Commando was a hurriedly thought-up, designed and built stopgap machine produced to spearhead the newly formed Norton Villiers (NV) company. It turned out to be the only machine to be produced by NV in the company’s nine years other than a few P11 hybrids and the 650cc Mercury workhorse; and production of these ‘leftovers’ ceased in 1969. The big twin became arguably the most iconic British motorcycle ever produced. The bike was voted Motor Cycle News’ ‘Machine of the Year’ a record five times. Nevertheless, it was certainly not perfect and there were many pitfalls along the way. It was produced in around ten derivatives, all based on the same original concept.

In forming his new company, NV chairman Dennis Poore, a former racing driver and CEO of parent company Manganese Bronze, soon became aware that the machinery he had inherited from both the former Norton company and Associated Motorcycles amounted to a collection of tired and unattractive designs. At the forefront was an ageing and unpopular 750cc twin, the Norton Atlas, which was a stretched version of the far more successful 500, 600 and 650 forerunners. The big twin suffered teeth-rattling vibration, and lowering the compression ratio by fitting pistons with dished crowns barely alleviated the problem.

Poore began thinking in terms of something new, a flagship machine. In his wisdom, he successfully poached from Rolls Royce one of their prominent designers, Dr Stefan Bauer, followed by Austin Motors’ development engineer Bob Trigg and Bernard Hooper and John Favill from the original Villiers company. Tony Dennis, formerly the Woolwich drawing office manager, joined the design team.

In the interim, several new engine designs had been considered, none of which could realistically be adopted given the cost and time required in designing and developing a replacement for the Atlas twin. An ohc twin motor, designated the P10, showed little promise, so it was decided to continue with the Atlas engine.

Dr Bauer joined the company with no motorcycling background, but with his sound grasp of engineering he very quickly concluded that, despite its incredible racing pedigree and worldwide popularity with the motorcycling fraternity, the successful ‘featherbed’ chassis had to go, much to the surprise and chagrin of the old school. Believing the heavy tubular construction failed to lend itself to his task of smoothing out the inherent vibration produced from the big 360-degree twin, he came up with a radical new design, bearing little resemblance to its forerunners. A single 2¼in (57mm) main spine – in its original form, with gussets to stiffen the connection to the steering tube – formed a kind of inverted keel, containing any torsional or twisting tendencies. Suspended from this large tube via rubber bobbins and within a lightweight 1in tubular structure, the old motor was bolted to a cradle that included the primary transmission and gearbox. To isolate the rider from the expected vibration, it was decided to mount the engine and gearbox cradle on rubber bushes, located in a tube at the rear of the cradle and suspended on a ½in-diameter stud, which was supported in two lugs either side of the mainframe. At the front of the engine was bolted a further tubular construction also containing rubber bushes, this time suspended on a ½in bolt and supported on two more frame lugs. Abutments and shims were used to prevent lateral movement, and to maintain constant or near constant chain tension to the rear wheel, the rear fork, or swinging arm, was pivoted from the cradle as close as was practical to the gearbox output shaft and drive sprocket.

The rather radical new bodywork styling, complete with a large green blob mounted on the fibreglass fuel tank, and a similar green disc on the facia of each of the fork yoke-mounted instruments, was dreamed up by the established marketing wizards Wolfe Olins. The blob was intended as a brand mark from which the Norton could readily be identified, and green discs appeared on much of the advertising literature that followed.

The prototype Norton Commando, later christened the Fastback, made its public debut at the 1967 Earls Court Motorcycle Show, amazing the big crowds with its unorthodox styling. Two machines were assembled at the Norton Villiers factory at Marston Road, Wolverhampton by Woolwich development department personnel Eric Goodfellow, John Mclaren and Jim Boughen. The bikes were presented in silver livery, with a bright orange seat. Not everyone was impressed, but there was nevertheless something rather special about the new Norton. Making the most of the engine they had inherited, the team had cleverly tilted the motor forward, giving the impression of speed, almost as if the bike was in motion before it was even rocked off its centre stand.

Public response was overall fairly positive, and by March 1968 production was well underway, with the chassis fabricated at the Reynolds factory in Birmingham and engine and transmission components manufactured at the old AMC factory at Plumstead Road, Woolwich, where the machines were also assembled after the chassis were delivered from Reynolds. Each machine was road tested, and after any required rectification, the completed bikes were distributed to the growing number of UK dealers and – more importantly – the eagerly waiting North American market.

The New York-based Berliner Motor Corporation was initially chosen as the main US distributor, having previously handled the trickle of AJS, Matchless and Norton imports. Later, Norton Villiers set up their own west coast establishment, Norton Villiers Corporation, at 6768 Paramount Boulevard, North Long Beach, California. Sales began to increase dramatically, especially after the introduction of the Roadster and S type, the latter clearly intended to meet US approval.

In 1968, reports began reaching the UK of some machines with bent or cracked frame tubes. Woolwich development department engineer John Mclaren was despatched to Berliner to investigate. He soon discovered the problem was occurring before any of the bikes were removed from their crates. It was the practice of the packing department back at Plumstead Road to remove the front wheels and clamp the front end of the bike to the floor of the crate via its front wheel spindle. The wheel itself was packed separately in the crate. However, some handlers, when delivering the crates to their destinations without a fork lift, would shove the crates off the delivery lorry end first. The machines that crashed to the floor rear wheel first survived intact, but for some of those that fell front first, the shock was enough to bend the frame’s 1in-diameter front down tubes out of true. In some instances a small crack would form. A team was sent to replace the damaged frames but it was soon decided to return the remaining faulty bikes to the UK for remedy.

In late summer 1969, Norton Villiers relocated, with government assistance, to Andover in Hampshire, where a new factory was built. Conveniently, 5 miles (8km) west down the A303 was the Thruxton racetrack, which offered valuable testing facilities, and in due course the Norton Villiers development department was established adjacent to the recently remodelled race circuit. Named the Norton AJS Competition and Development Department, and run by Peter Inchley, who with John Favill developed the AJS Stormer motocross machine at the Villiers factory in Wolverhampton, the premises were shared with the AJS Stormer motocross facility.

One of the two prototypes assembled at Wolverhampton and pictured on display in Stockholm, Sweden in 1967.ANDERS ‘NORTON’ LARSSON

The engine and transmission assembly moved to the Villiers factory in Wolverhampton. Delivered by lorry, the assembled engine and transmission units joined the assembly line in Andover. The completed machines were once again transported by lorry to Thruxton, where a newly formed Test and Rectification department just a stone’s throw from the Norton AJS unit was established. Here the bikes were oiled and fuelled up and fitted with dummy exhaust systems to avoid blemishing the chrome finish. Similar to the Woolwich procedure, each machine was run up, the ignition adjusted by stroboscope followed by the carburettors, then the bike was given a 10-mile (16km) road test and any faults remedied. The bikes were then loaded back onto the lorry and returned to Andover, where they would await despatch to the waiting dealerships. You might wonder how on earth they made a profit!

Officially named Fastback in March 1969,the bike was followed by numerous model variations including the R, which was basically a Fastback with conventional seat, mudguard and fuel tank; the S, with high-level exhaust exiting from the left-hand side; the SS, a street scrambler-styled machine; the Interpol police version; the Fastback Mk 2 and 3 with upswept exhaust and reversed cone silencers; the High Rider, which was a rather diluted attempt to attract the Harley-Davidson ‘Easy Rider’ fraternity, with high handlebars and a short seat with high tail. The Roadster, a production racer, the much maligned Combat, the Interstate with large 5-gallon (22ltr) fuel tank, a short run of club racing bikes (the Thruxton Club), the JPN Replica, and finally the 850cc Mk 3 with an electric starter, disc brakes front and back and other refinements, completed the line-up. Despite oil leaks and reliability issues including the crippling Combat debacle (covered in detail in Chapter 8), and encouraged by an energetic publicity drive, the Fastback achieved worldwide sales way above expectation. The North American market was by far the most buoyant, taking the biggest share of Andover’s output.

In late 1970, the Thruxton development department relocated to the Wolverhampton works in Marston Road, making way for Dennis Poore’s freshly formed Norton Villiers Performance Shop (NVPS), which employed the majority of the former Thruxton development staff. The company’s sole purpose was to manufacture the ‘Yellow Peril’ 750cc production racers and produce Commando performance components.

The 750cc Commando was in production from March 1968.ANDERS ‘NORTON’ LARSSON

The original Norton-AJS competition and development building, still in use in 2019 at Thruxton. It was later renamed NVPS (Norton Villiers Performance Shop), where the ‘Yellow Peril’ production racers were built, followed in late 1971 by the JPN (John Player Norton) works racers.

The Test and Rectification premises at Thruxton Circuit, still standing in 2019.

In April 1973, Norton Villiers introduced their 828cc Commando, which was marketed as an 850. Produced in several variations – the Roadster, Interstate, and race bike lookalike the JPN replica – the bigger engine model proved to be a more reliable motorcycle with even more torque than its 750cc predecessor although not quite as fast. By 1974 all production returned to Wolverhampton. The Mk 1a and 2a 850 were introduced with a revised exhaust system and airbox and often regarded as the best Commandos of all.

North America was not over-enthusiastic about the Commando appearance, leading to a rapid restyling exercise and the Commando R type. Only around 600 were produced, but the appearance led to the well-received Roadster.PHIL EDWARDS

Now named the Fastback, this Mk 2 came with restyled upswept exhaust.

Two Roadsters posing in front of one of the two original Test and Rectification buildings at Thruxton.

One of the many appealing posters distributed to the dealers.

In February 1975 production ceased on all previous models and the assembly lines were cleared to accommodate Norton Villiers’ last hoorah, the 850 Mk 3 Electric Start. This had American-style left-hand gearchange, a rear disc brake, the same Mk 2a redesigned exhaust and airbox to accommodate modern noise and emission controls, revised handlebar switchgear and uprated alternator output. Not the most reliable of additions, the starter generally underperformed.

In the same year, Dennis Poore took control of the failing Triumph-BSA factory at Meriden, regrouping under the Norton Villiers Triumph banner (NVT), which ultimately led to financial doom. The Asian onslaught had gained a significant foothold in Europe and America with a selection of sophisticated, reliable motorcycles. Sales slumped, and with the UK government calling in a large loan by 1976, it was the end of the road for NVT and the receivers were called in.

Thanks to some wheeling and dealing, stocks of Mk 3 850cc components were salvaged and a further batch of complete machines was produced in 1977. Remaining spares went to the newly formed Andover Norton Ltd and distributed to remaining Norton dealers.

The mighty 850cc Mk 3 in Roadster form. It was the end of the line.

It seemed a lot in those days. RAY WALES

Bernard Hooper and John Favill formed Norton 76, a company with a small band of workers to produce their own Commando utilizing Italian components and an SU carburettor. Lack of finance led to disappointment and just the one prototype was built.

WHERE ARE THEY NOW?

John Favill, who designed the Villiers Starmaker two-stroke transmission before he rejoined NV on engine and transmission development, continued his career with Harley-Davidson, managing the development of their Evolution engine. He now resides in Canada.

An original NV leaflet produced in 1967 to tell the world what was coming.

The team’s legacy: a fitting tribute to the small band of innovative engineers who made such an impression on the world of motorcycling.

Bernard Hooper continued with his stepped piston two-stroke design, which he had begun during his tenure with NV. He eventually set up his own research and development establishment near Wolverhampton. He died in 1997, aged sixty-nine.

Tony Dennis joined AMC in 1956 and rose to be manager of the drawing office. Tony migrated to Wolverhampton to continue in the design department until closure. He then moved on to Shenstone, where he worked on the Rotary development. He died in 2004.

Bob Trigg joined Yamaha as design and development engineer. After retirement he remained available as a consultant. He died in February 2019.

Dr Stefan Bauer moved to NVT’s Triumph and oversaw development of the Triumph T140 chassis before returning to the nuclear industry where he once worked. He died tragically, falling through thin ice whilst skating on a frozen lake on his country estate.

Peter Inchley continued to oversee the development department at Thruxton. When development moved up to Wolverhampton, he remained at Thruxton and took charge of the manufacture of 119 ‘Yellow Peril’ production racers under the new NV subsidiary Norton Villiers Performance Shop (NVPS). Each one of the machines was tested on the adjacent race track. In late 1971 he left to concentrate on his new company, Hitac, manufacturing water-cooled Suzuki race engines. Peter died in 2003.

Return to Racing

It came as a surprise when in October 1971 it was announced Norton would return to international racing with sponsorship from the John Player tobacco company. The new race bikes, designed by Peter Williams, would be built by the existing NVPS personnel under the management of ex-Grand Prix rider Frank Perris. The new team, John Player Norton, would go on to experience both extremes of success and failure – but that is another story altogether.

Restoration The act of returning something to its original condition.

None of my former Norton Villiers (NV) staff colleagues can agree on just how many Commandos were built during that memorable time from 1968 to 1977. In fact, a small additional number were assembled during 1978 from spares retrieved from under the receiver. Former NV senior sales executive Mike Jackson has mooted a figure of around 55,000. Whatever the figure, there do seem to be plenty left, and decades later some even find their way back home to Thruxton, where the Andover-produced machines arrived on a lorry, fully assembled from the new factory 5 miles (8km) east along the A303.

The initial Test and Rectification department was based at Thruxton circuit industrial estate, where each machine was prepared for road test. First, they received oils for the engine, gearbox and primary transmission, followed by dummy exhaust pipes so the resident ones would not be discoloured; the tyres were pumped, engines run up, ignition timing corrected with a stroboscope and finally the twin Amal concentric carburettors were set at the correct tickover speed. Each machine was then given approximately 10 miles (16km) on the road, or if the testers were lucky, five or six laps of Thruxton race circuit. After the test session, back in Test and Rec., as it was known, any problems were rectified, the dummy pipes replaced with new, scratches and imperfections to the bodywork dealt with, and any remedial engine work left to engine supremo Ray Simmonds. The bikes then returned by lorry again to Walworth industrial estate in Andover to be crated and sent to the dealers.

A typical ‘basket case’ collection of parts. This particular lot appears almost complete.

A 750cc Interstate that’s perfect as a basis for a ground-up restoration. Look out for this one later in this book.

Yes, I did say ‘back home to Thruxton’ because adjacent to the original Test and Rectification plant is my Commando hospital, where enthusiasts bring or send their machines for attention. Some of these bikes have been in the family for many years, owned from new in some cases, and return annually for servicing. Some are re-imported in containers by classic motorcycle dealers hoping to satisfy a growing band of restorers; these are sold as seen or, in many cases, after a quick paint job and polish, put onto an internet auction site and sold as ‘restored’. Some turn up after having been abandoned in barns for decades, or having lingered for years under a tarpaulin at the bottom of the garden, replaced by a first car as newly-weds begin family life, a recommission that may eventually get done. Whatever the source, there are still opportunities out there to find a suitable example for restoration.

BE PREPARED

Choosing the right subject for restoration may be the most important move the restorer makes. The Norton Commando is not your conventional British classic: by virtue of its past success and popularity it stands out from others. Knowing why the Commando was and still is so popular will be a big advantage to the restorer, and for those without experience and who wish to take on a ground-up restoration, then choosing from the dozens of books written on the subject should be a must before spending money on the first one that comes along. It’s always useful if you can find someone with previous Commando experience and knowledge to glean information from and who will ideally come with you to view any potential purchase.

In general, and especially for the uninitiated, the smoother path to success would be to find a complete bike rather than a basket case of bits, as almost certainly not all the bits will be there. Even though some of the complete bike may be unsalvageable, at least having the parts, whatever their condition, will help show you the bigger picture.

A big advantage when restoring a Commando is the now almost 100 per cent availability of genuine spare parts, marketed by Andover Norton, the company set up by NV chairman Dennis Poore and run by Mike Jackson after the doors closed at Andover and Wolverhampton. By obtaining large amounts of spares from the receivers and the rights to produce genuine parts from the factory drawings and some of the retrieved jigs and fixtures, they were able to save many of the world population of Norton Commandos. The company now thrives under the ownership of German entrepreneur Joachim (Joe) Seifert, who oversees a continuous expansion of parts and services available direct from Andover or via official outlets worldwide.

Several other firms began producing pattern parts but some of these fall short of acceptable, so the wisest choice for replacement parts would be the genuine items. As an example, some pattern isolastic rubber mountings, the very heart and soul of the Commando chassis, are manufactured with an incorrect shore hardness (the recognized measure of the resistance a material has to indentation), and the result is anything but the smooth motorcycle planned by Bob Trigg and Co. Then there are exhaust header pipes that foul the kick-start, are not symmetrical at the exit (or the entry, for that matter), or are prone to fracture at the neck. Read up on the subject, ask questions, join an organization such as the Norton Owners Club, and do not believe everything you read on the internet.

The primary chain looks past it but the other components will come back to life.

Commando restorer Phil Baker has some words to say on the subject. He has owned several machines over the years and now enjoys buying worn out examples to renovate.

Buying a Norton Commando

by Phil Baker

My reasons for buying Commandos have changed over the years. My first, a 1972 Combat Roadster, went like the wind, and went around corners in squares thanks to worn isolastics and swinging arm that swung. I loved the bike but eventually sold it to a mate who pulled it apart and never got around to putting it back together again, so I bought it back, and so began my lifetime relationship with the Norton Commando. I crashed it eventually and copped a broken leg. I have owned many Commandos and enjoyed restoring them from filthy horrible wrecks to gleaming machines. The following points are things to look out for.

If the bike has been imported, is there a Notification of Vehicle Arrivals (NOVA) certificate with it? If not, you could be tied up for years with the admin so it’s better to find another machine. If it has a NOVA, all you need to do is get the bike an MOT certificate, fill out a V55/5 form and send it with all the other stuff required by the authorities to the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Authority (DVLA), who will register the vehicle with a UK plate. If you want an age-related plate you will have to provide enough information and a Norton Owners Club dating letter to satisfy the DVLA that your bike merits one.

Matching frame, engine and gearbox numbers is a relatively recent fad and, for anyone who just wants a decent bike to ride, completely irrelevant. However, if you want the bike to be easy to sell when the time comes, matching numbers may well swing the deal.

This early Woolwich engine has been neglected to say the least. The good news is there are no broken fins. Separating the cylinders from the pistons is going to present a challenge.

Does the engine run? Does it matter? Well, it will in the end but is not necessarily a barrier to buying the bike. These are reasonably simple engines and genuine parts are obtainable at fairly sensible prices. Second-hand parts suitable for restoration are also to be found on auction sites and through club membership. The bike might need a re-bore, pistons, big end regrind and shell bearings etc and cylinder head reconditioning – not a big problem but more money to find. Is the frame straight and undamaged? Look for cracked paintwork, as that’s often a sign of damaged frame tubes. Wiring and electrics, chrome and wheel rims also all need to be considered in the budget.

I could go on for ages but there’s only one rule that you really need to apply: avoid allowing your heart to rule your head.

‘I’ve just reassembled the engine using all new parts,’ I was told by the seller of a Roadster recently. It needed work but seemed a good buy, so I bought it for a lot more than I would normally pay. The so-called ‘rebuilt’ engine turned out to be a collection of odd bits, nonmatching pistons, a bent con rod and odd piston rings – and included in the price was all the debris from a bead blast operation still present in the bottom of the crankcase, tappet tunnels and cylinder head.

BUYING ONLINE

In recent years my team has dealt with some appalling examples of internet auction purchases, some clearly illegal, most just plain rip-offs. It is amazing how a couple of coats of aerosol paint, a polished timing cover and some black tyre dye can make a motorcycle look half decent in an internet auction photo to someone inexperienced and keen to own a Norton Commando.

Sometimes the purchaser is not so much naïve as bordering on insane. I had a call one Saturday morning several years ago from a chap who asked if he could bring his newly purchased Commando down for me to ‘check the carbs and ignition’ as he could not start the bike. This Interstate turned up on a trailer sprayed a sickly thin orange, with runs included, and the Norton tank decal at 30 degrees. Next thing I noticed, the steering stem nut, minus lock tab, below the lower yoke was loose. While the unfortunate owner revealed the details of his purchase, my curiosity awakened, I slipped a socket onto the nut and nipped it up. The steering seized tight. Whoever had thrown this machine together had omitted the steering bearing spacer, so nipping up the nut had pulled the two bearings toward each other, locking the steering. This was alongside over twenty further major faults, including worn-out pistons, both minus piston rings, 6in (15cm) of sway at the rear wheel, missing spokes, inoperative gearbox and solid forks. Most horrifying of all, it was sold with a brand-new MOT certificate for £7,000 by a car dealer, who delivered it on a trailer to a car park; the buyer didn’t even ask to hear it run.

After rebuilding the machine, I wrote a twenty-four-point report and suggested he contact the authorities. His response was, ‘I do not want a brick through my window.’ Any sympathy I might have had dissolved immediately. That machine cost almost as much as the purchase price to bring to satisfactory condition. It was bought as a runner, not a restoration project, which at a fraction of the purchase price would have made an excellent restoration project. I have more examples, mostly bought at online auctions. I am sure there are plenty of good, honest sales from the same source, but until there is some way to weed out the bad guys, be careful. Never has the warning ‘buyer beware’ been more significant.

It can be a gamble buying from any source, bearing in mind you can’t see inside the engine and gearbox so have to rely on the word of the vendor, but then the purpose of the exercise is to restore a machine hopefully to the best of one’s ability, and so that will generally mean an engine strip and examination. Size of budget and mechanical know-how are obviously significant factors, not only when choosing the restoration project, but also financing its progress back to glory. Replacement parts to purchase and professional work you may have to outsource, such as vapour cleaning, paintwork, wheel building, even the engine and gearbox, all have to be factored in.

Up on the bench and ready to dismantle, this original NVPS production racer makes a good restoration project.

There are any number of classic bike magazines on the newsagent shelves with pages of potential buys. I hesitate to say ‘bargains’ as these do seem more and more difficult to source, the value of the product being well appreciated by all. The Norton Owners Club has branches worldwide, and joining one will give access to all kinds of help and information. They have a spares outlet, technical help, rallies and social gatherings, a great website and a monthly magazine,where there is always a good selection of complete runners, restoration projects and used spare parts for sale. Being lucky enough to find what you are looking for here is probably a safer bet than taking a chance buying from an anonymous source on the internet.

MIX AND MATCH

One attractive aspect of setting out to renovate a Commando is that, along with the substantial spares back-up, you have the opportunity to produce any one of a dozen or so variations of the bike, all assembled around pretty much the same basic rolling chassis. There were of course two significant frame changes, not including the very early correction to a weak steering head, and there were some further minor changes to the 1975 Mk 3 attachments, but without being too pedantic on detail, swapping bodywork and exhaust systems, wheels and brakes, fuel tanks and seats, can produce almost whatever model you choose.

Modern fuels now contain a significant amount of ethanol, at present around 8 per cent in the UK and more in the USA. It is used to oxygenate the petrol, which allows the fuel to burn more completely, producing cleaner emissions. Unfortunately, the ethanol will destroy fibreglass fuel tanks and damage some fuel lines, carburettors and fuel tap seals. The early Norton Commando fuel tanks were made from fibreglass, so you may wish to bear in mind the ethanol problem when choosing a machine. There are products available to coat the inside of a fibreglass tank to protect it from ethanol corrosion, but some countries have banned this type of fuel tank all together. Ethanol also attracts moisture from the atmosphere, causing rust to form, generally on the underside of the top skin of the steel fuel tank. This then dissolves with the fuel and passes through the filters and into the carburettors. Again, there are good products available to seal and protect the inside of the tank and the subject is covered in Chapter 10.

Most enthusiasts make do with the garage to keep and maintain their bike, sharing the space with the tumble drier, the artificial Christmas tree propped up in a corner and a redundant dog basket containing car shampoo and polish bottles. The car sits on the drive, of course. Some may have a shed big enough to squeeze a Roadster through the door, and precious little else.

Professional specialists in the field of classic motorcycle renovation and maintenance are rather thin on the ground, which is not really surprising because most owners have sufficient knowledge to maintain and repair their bikes sufficiently to keep them running, much like it was in the days when British motorcycles ruled, long before the advent of plug-in computers to determine the source of a misfire. But to what degree of maintenance? Changing the oil and filter, checking the tyres and other general servicing is well within the ability of most. However, essential attention to chain tension, both primary and rear, wheel alignment, valve clearances, isolastic suspension adjustment and more seem not to be within the capabilities of many owners, judging by what I observe passing through the workshop. Hopefully the following chapters will help owners improve the quality of maintenance applied to those surviving ‘Machine of the Year’ Nortons.

THE WORKSHOP

The professional classic motorcycle workshop is always a place of interest and pleasure to most visitors, not only for the array of bikes in various stages of dismantle, but also the range of machinery – from an elderly Harrison lathe, mill and swing press to the electric and gas welding plant – the old Shell oil and Champion spark plug posters on the wall and, most profoundly, that unique smell of oil and machinery.

Let’s assume for the moment that we have almost every convenience necessary to complete a full ground-up renovation. What was previously a double garage is now kitted out sensibly into a spacious workshop, with plenty of light, including a portable bench spot light, a work bench, a secure engine mount, shelves and a hydraulic bike bench to lift the bike to a convenient level to work on. These bike-lifting benches are available from several popular outlets at very reasonable prices. I well remember after the NVT gates closed for the last time I took a new position with Honda and spent time at the Honda race department in Japan. The Japanese race mechanics all worked on the bikes at floor level and spent their time squatting to carry out the procedures. I found that tough on my knees.

A parts washer complete with electric pump makes light of washing oily engine parts, and portable air compressors are reasonably priced and very useful. Other essentials include a bench grinder, polishing mop, vice, pillar drill and a heat source such as a portable mini oxy-acetylene plant, which can be used for heating engine parts as well as welding and brazing. If the welding plant is a little too ambitious, a propane gun and gas cylinder will generally provide enough heat to expand alloy castings such as cylinder heads and crankcases for assembling valve guides and bearings. There are also some very good gas or electric workshop bench ovens on the market, although unless you have other similar projects lined up, it will hardly be very cost-effective. The kitchen oven is as good a place as any if you can get away with it, but I will not be recommending you try. I heated a pair of crankcases in my mum’s oven when I was a lad. She caught me and I still shudder at the memory of her wrath over fifty years on. Perhaps if I had degreased them first, I may have got off more lightly!

Workshop heating should also be considered, as not a lot will get done in a cold workshop midwinter. You could include a bead-blasting cabinet to prepare smaller cycle parts for painting, if this is a task to be done ‘in house’, although using a professional paint company for painting and preparing larger items such as a frame and bodywork may be the sensible route to the best end result; creating a perfect paint finish to side panels and fuel tank with lining will exceed most people’s capabilities. Obviously there will be jobs that must be left to the specialists, such as cylinder rebores and crankshaft grinding. Finally, a small lathe will never be left out of use for long, and a power washer will make short work of a grubby machine before wheeling or maybe carrying into the workshop.

A well-lit working environment with space to move will make work on a project a joy.

A parts washing facility is a must and the toothbrush gets to places other gadgets cannot reach.

Up and away off the floor saves an aching back.

This home-made rotating engine stand has been in use for many years and makes engine work so easy.

The polishing mop used with a suitable soap will, with practice, produce a quality finish, saving time and money over outsourcing.

The front end bike stand is convenient to use and give good access to the front wheel, forks and steering.

It’s doubtful that many renovators will have all of the above facilities, but there are professionals able to take on work that is out of reach of the average person. In any case, there is more than enough work for the amateur to be getting on with – stripping the bike down, storing the parts, examining and measuring the engine and transmission parts and so on.

One legacy inherited from the previous twin-cylinder engines, produced since 1948, was that each Commando right up until the end of production in 1975 left the factory assembled with around six variations of screw thread, requiring Whitworth and American fine (AF) tools. There were no metric fasteners anywhere on any Norton Commando when they left the factory and it’s rather annoying to find cycle parts secured with them years later.

TOOLS FOR THREAD REPAIR

Thread repairs are often required, especially in aluminium castings. Correct replacement thread inserts are given for failures in the following locations.

Location

Description and length

¼in Whitworth fork/front mudguard bridge threads

¼in × 1.5 Whitworth

¼in Whitworth exhaust rocker cover stud threads

¼in × 1.0 Whitworth

¼in BSC gearbox outer cover screw threads

¼in × 2.0 BSC

¼in Whitworth primary chaincase threads (Mk 3 850)

¼in × 2.0 Whitworth

5

⁄

16

in BSF head steady threads

5

⁄

16

in × 1.5 BSF

5

⁄

16

in BSC front upper cylinder stud threads

5

⁄

16

in × 1.0 BS

Replacing a damaged or worn thread will require the correct tap, insert tool and thread insert, all of which can be sourced from a specialist supplier.

One of the most common repairs is the 1.997in × 14 TPI cylinder head exhaust port thread and this will normally require professional attention. Details can be found in Chapter 8.

Most Commonly Required Hand Tools

Combination spanners are most useful, comprising a ring spanner at one end and an open end at the other. A selection of sockets is a must; 3⁄8in socket drives will cover most applications, although for heavier work, such as the crankshaft generator nut, clutch centre nut and wheel nuts, a ½in drive is preferable.

¼in Whitworth combination spanner

3⁄16in Whitworth combination spanner

5⁄16in Whitworth combination spanner

9⁄16in AF combination spanner

¾in AF combination spanner

½in AF combination spanner

7⁄16in AF combination spanner

15⁄16in AF combination spanner

5⁄8in AF combination spanner

3⁄8in drive socket bar and 6in extension

½in drive 1in AF socket

½in drive ¾in AF socket

3⁄8in drive ½in AF socket

3⁄8in drive ¼in Whitworth socket

3⁄8in drive 7⁄16in AF socket

3⁄8in drive 14mm spark plug socket

3⁄8in drive 7⁄8in AF socket

½in drive 1in Whitworth socket

½in drive with a 3⁄8in adaptor torque wrench

Other hand tools required to cover most applications include:

Screwdriver set

Philips screwdriver set

Pliers

Pointed pliers

Side cutters

Imperial socket (Allen) key set

Mole grips

Tyre pressure gauge

Set of pin punches

Selection of files

Wire insulation stripper

Medium-size ball-peen hammer

Rubber mallet

Telescopic magnet

Impact screwdriver set

Wire brush

Stiff toothbrush

Rear suspension spring C spanner

Circlip pliers (expanding and contracting)

Feeler gauges

Selection of needle files

Bullet crimper

MEASURING INSTRUMENTS

Measuring instruments are essential. You will need a steel straight edge, inside and outside micrometers and a vernier gauge to measure items such as pistons, cylinder bores and crankshaft journals. More specialized equipment includes a dial test indicator (DTI) with a 14mm spark plug adaptor to measure top dead centre (TDC) and crankshaft end float, and a degree disc for more advanced work such as checking the accuracy of the degree plate inside the primary outer chaincase and ignition timing. For competition work, the degree disc may be required when checking valve opening and closing, but is not generally necessary when building a road engine; the timing dots and dashes provided are all that is required for optimum performance. Always have a multimeter for checking the electrics.

Any precision work will require good measuring instruments.

FACTORY TOOLS AND EXTRACTORS

There are parts attached to the Commando that will require the correct factory extractor to remove and replace. Engine and transmission items such as the timing side crankshaft pinion, clutch spring and engine main bearing inner race cannot be shifted without the right tool. There are universal pullers or extractors for other parts, such as the camshaft sprocket and valve compressor, and it’s not difficult to turn up on the lathe a simple drift for removing and replacing valve guides where the factory tool (part no. 063964) is not at hand. There is a factory valve seat cutting tool (part no. 063969) or, as an alternative, some more expensive but very good sets on the market include the Neway VS range with 46-, 15- and 60-degree tungsten carbide cutting blades.

A degree disc is used to set precise ignition timing on the bench, and in some instances to check valve timing.

The dial testing indicator (DTI) or clock gauge is measuring the end float on this crankshaft.

The only way to remove a main bearing inner race without incurring damage is with a hydraulic extractor, unless of course the crankshaft is so worn that there is insufficient interference fit.

Some tools can be home made. For example, you can fashion an engine drive sprocket extractor from a piece of 1in (25mm) × 3⁄8in (10mm) steel bar with two 5⁄16in (8mm) holes drilled 2¼in (57mm) apart, with a further hole tapped ½in UNF or similar fine thread centrally between the two smaller holes, into which threads a hexagon-head bolt approximately 3in (75mm) long, and two 5⁄16in UNF studs 6in (15cm) long with washers and nuts will make a suitable extractor for both Mk 3 and earlier engines. All Commando engine sprockets have two 5⁄16in UNF threaded holes 180 degrees apart for extraction purposes.

There is one item that is invaluable when dismantling a Commando and it is easily made from some cheap tubing. It’s not quite so vital when working on pre-1969 machines with the centre stand located to the frame, but is essential with later bikes, where the centre stand pivots from the engine cradle, because removing the engine means the cradle and stand become unattached at the front and pivot freely on the ½in rear isolastic stud. The bike will of course collapse. Therefore, before removing engine and gearbox, support the bike under the rear frame loop with a simple structure made from 1in (25mm) square tubing, with some short pieces of 1in-diameter round tubing and one length of ¾in (20mm) bar. Two pieces of water pipe insulation wrapped around the support bar and positioned under each rear frame loop tube will protect the paintwork.

If at all possible, construct a support structure similar to this.

The support legs need only be long enough to raise the rear wheel an inch (25mm) or so from the floor.

The finished item should look like this.

This support is especially useful when dismantling post-1970 Commandos where the centre stand pivots from the engine cradle.

Factory Part Numbers

060949Auto advance lock washer060999Clutch spring compressor061015Clutch lock tool061359Contact breaker oil seal guide063964Valve guide extractor and inserter063965Peg spanner063968Exhaust lock ring tool063970Main bearing inner race extractor063971Isolastic mounting assembly tool064292Oil seal assembly tools064297Sprocket puller064298Slide hammer064622Strap wrench067245Primary chain case inspection tool067524Crankshaft timing side pinion tool067624Sump filter and gearbox sprocket nut tool063969Valve seat cutter131781Piston ring clamp 750cc131782Piston ring clamp 850ccIt could be dangerous to try and remove the clutch spring circlip without a spring compressor, part no. 060999.

Special puller part no. 064297 makes light work of removing the taper fit engine sprocket.

OTHER TOOLS

Most of the miscellaneous items can be found in workshops and garages everywhere; not everyone will be familiar with Graphogen, however, which is a colloidal graphite grease used in the assembly of engines, gearboxes and some brake hose connections. The compound is suspended in mineral oil and is spread liberally over bearing surfaces, valve stems, camshafts and bushes. It will stick to the surface it’s applied to and maintain a skin of protection on start-up. It is also used to coat screw threads, especially aluminium threads. Spark plug threads, cylinder head bolt threads and the exhaust retaining rings will benefit from a light smear.

Similarly, products such as Ardrox or Rocol penetrant dye and developer are less likely to be found in the average workshop but are highly recommended when checking for cracks and leaks. Both items are featured in this manual.

These are some of the pretty much essential items to have within reach when maintaining or overhauling a classic motorcycle.

Two invaluable home-made tools – the long T bar for retrieving a fork damper rod from inside the fork leg, and the short one to lock and unlock the primary chaincase inspection caps.

A rudimentary sketch of a damper rod retriever tool dimensions.

There is a series of reprinted Norton Villiers factory workshop manuals covering all Commando machines, containing every piece of information necessary to assist both amateur and professional mechanics in the pursuit of renovation and maintenance excellence. There are also poster-size exploded views of engines, transmissions, brakes, carburettors, suspension and cycle parts to assist.

Last but not least, you should have a fire extinguisher. Take professional advice on what appliance is best suited.

Miscellaneous workshop items

Oil can

Cotton rag

Carburettor aerosol spray cleaner

General-purpose grease

Colloidal graphite grease

Liquid gasket

Storage bins

WD40 aerosol

Fluid measuring cylinders

Elastic bands

Developer aerosol

Torch

Broom

Dust pan and brush

Waste bins

Magnifying glass

1in (25mm) 100grit abrasive tape roll

1in (25mm) 800grit abrasive tape roll

Coarse sandpaper sheets

Penetrant dye aerosol

The following sequence for the dismantling of a Commando, based on a real example, is meant as a general guide and is not necessarily a prescribed method. Having the relevant Norton Villiers workshop manual and parts list catalogue to hand will be most helpful.

GAA 45K – A FINE EXAMPLE

This particular 1972 750cc Interstate Commando spent eighteen years propped against a farmyard barn in Surrey, England. As it stands, it is no exaggeration to label it a wreck. What can be observed from the outside is nothing to the horrors hidden inside.

Before entering the workshop, as much loose dirt and grime should be removed with a power hose. An airline is useful to dry off before mounting the hydraulic ramp. Note the front and rear support.

After many years of being abandoned to the elements, the original seat had rotted; this came as a possible replacement.

Up on the bench and supported fore and aft, ready to dismantle.

1.After draining off what oils still remain inside the engine, gearbox, oil tank and primary transmission, it is time to take a good look at what lies ahead. The large glass-fibre Interstate fuel tank at first glance looks fairly decent, probably because this particular item, along with the seat, was lying around on the inside of the barn. However, the tank’s underside was found to be badly cracked and the inside a total mess. This, along with the problems caused by modern ethanol-laced fuels, was enough to make the decision to scrap it in this instance, taking into account the relatively cheap cost of a new replacement balanced against the man hours required to return the old tank to an acceptable condition. On top of that the owner had expressed a preference for a Roadster Commando, with its smaller tank. Had the rotted interior been in better condition, the interior could have been sealed with an ethanol-proof lining, and a different decision made.

2.With plastic receptacles on hand to place parts, the dismantling can begin. The fuel tank and seat, its base rusted out beyond practical repair and the upholstery ripped and torn, were disposed of. It would have had to go anyway once the decision to return the bike as a Roadster was made, as the two seats differ. Remove all cables, as it is doubtful any will be serviceable, and unscrew the socket head screws to remove the carburettors and their manifolds. Once the carburettors are removed from Mk 1a, 2a, and 850 Mk 3 machines, the large black plastic airbox can be withdrawn forward from between the frame rails. There are three attachments, two ¼in hexagon-head fasteners securing the base to the battery tray and one ¼in nut, bolt and spacer connecting the box to the frame upper cross-member.

The carburettors will be replaced with a set of new Premiers from Amal.

The rotted wiring loom can be stripped out, as there will be little salvageable from it. The rectifier, Zenor diode, warning light assimilator and 2MC capacitor may well be useable but in this instance the decision was made to replace these items with a power box (seeChapter 11), encapsulating the battery charging components into one small container. This simplifies and reduces excessive wiring. The main switch is saved for examination and may well be salvageable.

The airbox looks past any hope but can nevertheless be put to one side for closer evaluation later. Before removing the oil tank, the feed and return oil hoses must come off, and the engine breather and vent hose pulled from their connections at the top of the tank. The early Fastback machines had a different oil tank, which also doubled up as an attractive right-hand side panel. With these tanks, the feed and return came off the front of the tank, as it did on the S type and 750cc High Rider Commando, which had their own central oil tank. On this later 1972 machine and all subsequent Commando models, the feed and return are found at the rear of the oil tank.

The engine feed hose is attached to the large banjo, while the return hose is connected to the steel tube to the left of the banjo. With the feed hose removed, the banjo bolt with its coarse filter gauze can be unscrewed with a 15⁄16in AF socket, allowing easy access to the return hose clip, which can be unscrewed and the hose slipped off. The two rubber mountings at the top of the tank are obvious, but hidden at the bottom is a ¼in UNF hexagon head screw, which passes through a sleeve and grommet in the base of the battery tray and threads into the tank. This fastener is difficult to reach. A 7⁄16in AF socket and universal jointed extension bar and ratchet will do the trick. Without the socket, it is a slow process with the correct size ring or combination spanner. The external oil filter, introduced in 1972, is attached to the right-hand (timing) side engine cradle plate behind the gearbox. With hoses still attached, bend back the lock tabs and unscrew the two short 5⁄16in UNF bolts to release the filter body.

The oil tank is removed with little resistance.

The battery tray and airbox look bad but they may well be retrievable.

The airbox back plate presents a challenge.

This mass of wires and connections will be replaced with a bespoke wiring loom a fraction of the size and space that this bird’s nest occupies.

3.Turning to the rear of the bike, this machine has a quickly detachable (QD) rear wheel. Release the speedometer cable and unscrew the axle from the right-hand (timing) side and withdraw the wheel, leaving the sprocket and chain still attached to the swinging arm. Without the wheel, the chainguard front ¼in bolt is easily accessed and can be removed. The chain oiler spout is attached to the chainguard and is removed before slackening the left-hand (drive) side lower suspension bolt. The chainguard can then be lifted away. The sprocket and brake drum can now be removed after unscrewing the rear brake adjusting nut from the brake yoke and unclipping the chain joining link to remove the rusted chain.

With earlier machines not equipped with a QD arrangement, the wheel is attached to its sprocket by three long sleeve nuts. Remove the three rubber bungs in the rear hub disc and with a 7⁄16in AF socket access the hub and unscrew the nuts. The wheel is then removed as before, leaving the sprocket still in position, which can be removed in the same way as the QD variation. Mk 3 rear disc brake wheels are removed in a similar manner, but disconnect the hydraulic pipe from the brake caliper before removing the axle. After withdrawing the axle, collect the caliper, still attached to its bracket, and put in store.

4.Unbolt the chromed footrest supports, then remove both Z plates by removing the 3⁄8in bolts and ½in rear isolastic stud nuts. Note the Zenor diode is attached to the inside of the right-hand Z plate. Release the ¼in nuts that attach the front of the rear mudguard to the battery tray and lift the tray away together with the horn, which is attached to the rear of the tray. The 850cc Mk 3, with the hydraulically operated rear disc brake, has a formed pipe connecting the master cylinder to a brass junction behind the right-hand Z plate. The junction has two exits, one connecting a flexible hose to the rear brake caliper, while the remaining horizontal connection accommodates the hydraulic brake light switch. Disconnect the pipes and detach the junction from the Z plate. The rear brake master cylinder, which is attached to the inside of the right-hand footrest support, and its attachments can be stored together with the rear brake caliper for attention later. Note the Mk 3 has two Zenor diodes, one attached to each Z plate.

Remove the tail fairing by unscrewing the support bracket and tail-light assembly, withdrawing the two hexagon-head screws and the single screw at the forward end of the fibreglass unit. The clip attaching the mudguard to the frame rear loop is now exposed. With the nuts retaining the front of the rear mudguard to the battery tray via a square bracket already removed (Fastback machines have just one front fastener), the rear clip can be removed, releasing the mudguard from the bike. Fastback machines have a slightly different rear mudguard-to-seat-unit attachment: the clip that locates the seat unit to the frame rail is positioned at the very tail end of the frame loop and is accessed via the gap between the seat unit and rear number-plate support.

Returning to the front of the machine, a soaking with WD40 will be necessary over the exhaust retaining rings, head-steady socket head screws and stud nuts before removal. The machine featured here required heat to the cylinder head before the socket head screws would budge. The exhaust rings came away without a struggle and the remains of the exhaust went straight to the skip. The four short ¼in UNF bolts retaining the coil bracket to the frame offered some resistance, finally giving way after a soaking with WD40.

Not a good idea! That’s exhaust abuse.

The rear wheel disc cover indicates this is a QD wheel, while the oxidation tells its own story.

5.Rather than attempt to remove the complete engine and transmission assembly as one, it is far more convenient to separate them first.

Open the previously drained primary chaincase. The method of dismantling the primary transmission, including the 850cc Mk 3 electric starter gear, is covered in Chapter 9 and requires special tools. The clutch compressor tool (part No. 060999) is essential and it can be dangerous to attempt to remove the large circlip without it.

Once the primary transmission is removed, with all machines other than the 850cc Mk 3, there are three ¼in Whitworth hexagon-head screws that retain the inner chaincase to the engine crankcase. Make sure that the crankcase has been drained of oil otherwise, when the lower screws are removed, oil that would have drained from the oil tank into the engine sump will flow out of the threaded hole, making a mess of the workplace. The 850cc Mk 3 inner case sits over four studs, which ultimately support the outrigger plate on which the generator sits. Further back, the case is supported on a threaded stud referred to as a chaincase steady, which has a nut and washer backing up behind the case and a washer and nyloc nut inside to lock the case in place. After releasing the starter cable, the starter motor can either remain attached to the case on dismantling or be detached in situ by unscrewing the two short and one long crosshead screws.

The 5⁄16in BSF socket-head screws securing the head steady needed encouragement in the form of heat to release their grip.

6.