Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Poetry Business

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

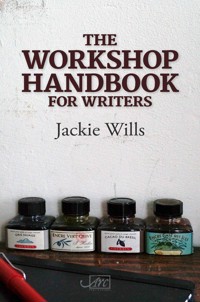

We begin with a drive to write something that's never been said before, to protest, to offload, to challenge or catch the zeitgeist. We imagine we write like the poets we admire. Slowly we learn the craft, understanding eventually that a writer is indentured for life. Drawing on decades of experience as a poet and tutor, this compelling book is part hands-on guide and part reflection on ways that poetry can make a difference to how we live. It is also a survey of many varied and inspirational writers, especially women poets from the end of the 20th century. The final section of this unique book offers starting points and resources that will prove essential for new and experienced poets alike. Jackie Wills is herself one of our most genuine and brilliantly insightful poets; and, as the sections on writing workshops show, she has helped people of all ages find their way into poetry.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 253

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

On Poetry

Published by The Poetry Business

Campo House,

54 Campo Lane,

Sheffield S1 2EG

www.poetrybusiness.co.uk

Copyright © Jackie Wills 2022

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

All rights reserved.

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Designed & typeset by The Poetry Business.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Smith|Doorstop is a member of Inpress

www.inpressbooks.co.uk.

Distributed by IPS UK, 1 Deltic Avenue,

Rooksley, Milton Keynes MK13 8LD.

ISBN 978-1-914914-12-6

eBook ISBN 978-1-914914-13-3

The Poetry Business gratefully acknowledges the support of Arts Council England.

Contents

Introduction

Part One: Reading Poems

One: Led by the Language

The Flea by John Donne

Thoughts after Ruskin by Elma Mitchell

Lapwings by Alison Brackenbury

Building a Personal Canon

Plath’s Rhetoric

Two: Deciding to Write

Being Fifty by Selima Hill

How Black Women Writers Defined the 1980s

The Fat Black Woman Goes Shopping by Grace Nichols

Brief Lives by Olive Senior

Three: Heroines and Heroes

More fun than Nigella by Lorna Thorpe

Paying Homage

Grief and Elegy

11 The Camp by Moniza Alvi

Four: Environment, Setting, Conditions

Digging by Edward Thomas

Re-writing Colonial History in Rime Royale

The Doll’s House by Patience Agbabi

Permission to Write on the Window

Naming Home

Pepys and a nightingale by Janet Sutherland

Five: What Gives Me the Right?

Hiss by Jay Bernard

Make Something New

The Fitting by Edna St Vincent Millay

Finding Your Place

The Fall by Pauline Stainer

Honouring an Ordinary Life

Poetry of Critical Illness and Death

How to Behave with the Ill by Julia Darling

The Details of Language

Gazebo by Martina Evans

The Older Woman’s Silence

Lunch by Lotte Kramer

Six: Politics and Social Engagement

The Poet as Witness

Social Engagement and Necessary Poems

On the 70th Anniversary of the Warsaw Uprising by Maria Jastrzębska

The Artists’ Take

Seven: Translation

A Bengali woman in Britain by Safuran Ara

If it Wasn’t for Translators

At the Edge of a Field, a Pair of Shoes by Wang Xiaoni

Part Two: Writing & Working with Poems

Eight: Running a Workshop

What Makes a Workshop?

Organising It Yourself

Working for Someone Else

Momentum

Keep Workshop Plans

Caution!

Evaluation

Nine: The Model

Critical Feedback Model

Change

Masterclass

Exercise Model

Ten: Planning

45 Minutes

Half-day

Full Day

Zoom Time

Two Days to a Week

A Course or Series

A Residency

Eleven: Developing Workshop Materials

Inventing Exercises

Set Your Own Boundaries

Collect Poems

Themes

Props and Postcards

Smells

Workshop Basics

Why Write by Hand and Not on an iPad or Phone?

Why I Use Models

Twelve: Working in Schools and Colleges

Primary Schools

Secondary Schools

Special Educational Needs

Case Study: West Sussex County Council Gifted and Talented Scheme

Case Study: Treloar College, Alton

What Schools Want

Thirteen: Writing Exercises and Prompts

Creative Dialogue

A True And Faithful Inventory … by Thomas Sheridan

The Creative Power of Form

Is It You or Are You Making It Up?

Childhood

Here and Now in the Material World

Your People

Zephyr by Catherine Smith

The News

Fourteen: Identity, Words in Gardens and Questions

Identity – are you a shapeshifter, a boaster, and who do you eat with?

Words – the perspective of visual artists

Asking Questions – Pablo Neruda’s final collection

Afterword

Endnotes

Quoted and Referenced Poems

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Further Resources for Writers

Introduction

In the decade I was a mother with young children I bought a calendar with a quote from a poem for each of the 365 days to come. Sometimes reading a couple of lines was about all I could manage but it meant that in the middle of making breakfast, finding shoes under the sofa, combing hair and packing up lunches, I’d hear Emily Dickinson speaking to me from another century and she’d set off a line of thought that walked with me up the hill and down to their primary school. I was juggling writing with earning a living and bringing up children, was often exhausted, but even so, those lines attached to dates were reminders of how lucky I was, and still am, to have the means to read, write, publish. In the old-fashioned way, I stuck some into an exercise book and my homemade anthology lives on a shelf next to my desk holding its pinpricks of thought.

For more than 20 years I’ve sat with groups of people at different stages of their writing lives, experiencing the liberation of metaphor – a child realising they can find words for the other worlds in their head, a man or woman released from the constraints of caring, illness or addiction, from fear of the past and the future, from the demands of work, for an hour or so by listening to a poem and writing their own. Poetry allowed me to do this. And when I read for myself, sometimes flicking through an anthology, sometimes concentrating on a collection for a book group, I am in awe of human invention.

When I began to earn a living running writing workshops, this work kept me reading widely, looking for new poets or poems to use as examples. It focused me on form, on what worked in a poem and it helped me understand how we use the tools of metaphor and language. I used model poems in writing exercises because a mechanic learns to put an engine together by taking it apart. I remembered a big old engine from my Morris Traveller suspended out of its rightful place when the head gasket blew. A poem has to be oily and heavy too. When I embarked on this work, though, I realised how little I’d read. I’ve come to terms with never catching up, but pledged to stretch as a reader. It’s humbling to face this truth about yourself, that however much you think you’ve read, it’s not enough. The flipside is to enjoy the many different ways people express the world, and to accept that there’s some writing you’ll get on with and some you’ll dislike.

The chapters in Part One are short essays that have come out of my reading. They explore how other writers feed what I write and that this is a continual process. I look at poets I read as a teenager and others I’ve come to later; I question the idea of a single canon through the lens of my own. I look at poets who keep me going because I admire what they’re doing with language, metaphor or form, innovators and poets who answer back. I question what gives me the right to write; I explore how poetry engages us, enters the public arena and how poets extend themselves translating others. I hope these ideas will be springboards to further reading.

Part Two of On Poetry provides hands-on strategies for keeping yourself and others writing, from writing prompts to running writing workshops, with all the preparation they demand. I cover planning, timing and evaluation, different approaches you can take as a workshop facilitator, how to invent your own workshop exercises and what you need to consider in different settings. I touch on visual artists’ use of text, where it meets poetry and how I’ve tapped into that fluid boundary. I include sample workshop plans, case studies and exercises. At the end is a book list and other resources.

I know people who write every day, others who have gaps lasting years, people who finish a book and say they’ll never write again, many who are still looking for a publisher who believes in them. The poets James Berry and Vicki Feaver were tutors on the first Arvon course I attended. I’ll never forget Feaver’s advice, ‘go deeper’ and on the train back from Yorkshire, Berry’s, ‘have stamina, believe in yourself.’ The many writers whose work I look at here are also testament to their wisdom.

Part One

Reading Poems

One

Led by the Language

It must have been around 1970. I was carrying three books: The Mersey Sound featuring Brian Patten, Roger McGough and Adrian Henri; Penguin Modern Poets 8 featuring Edwin Brock, Geoffrey Hill and Stevie Smith; and an anthology of Georgian poetry, first published in 1962. I bumped into my English teacher. She took them out of my hands and then her comment shook me. It was vehement. Personal. I couldn’t like all of them. The Liverpool poets were in direct opposition to Geoffrey Hill. I felt stupid and confused. I couldn’t understand her way of thinking. I simply liked Smith and Hill, I liked Patten, Henri and McGough. I adored Dylan Thomas and Sylvia Plath. Hendrix was alive (he died a few months later) shaking things up.

The 1960s had chucked choices at 1970 that were too threatening. It was only 25 years since the end of World War Two, rationing ended months before I was born. Writers, musicians, artists were busting out of unbearable restrictions. She must have felt under siege, a woman who thought she knew what poetry was. I was floundering too, curious, drawn to the range poetry offered and that range was most evident in language. My teacher had been sold a very limited canon, poor woman. So I knew poetry would provide me with more than a rule book. Rumer Godden writes in her autobiography A House with Four Rooms, ‘everyone is a house with four rooms, a physical, a mental, an emotional and a spiritual. Most of us tend to live in one room most of the time but unless we go into every room every day, even if only to keep it aired, we are not a complete person.’

In those few lines, Godden describes the range of poetry I wanted to read. I went through a mystical phase, reading St John of the Cross and Mum’s collected Cecil Day Lewis. Around about that time Mum was doing English A level and read me poems aloud by John Donne. She particularly loved ‘The Flea’ – tickled by the metaphor, ‘in this flea our two bloods mingled be …’. Me too, possibly for different reasons, since I was being taught in a convent where my teachers’ mission was to prevent sex before marriage. Here’s Donne flagrantly placing those Anglo-Saxon ‘sucks’ in line three, words that read simultaneously as ‘fucks’. How Donne fitted into the spirit of the sixties! Go on, sleep with me, the decade screamed and a cheer answered from nearly four hundred years back.

The Flea

by John Donne

Mark but this flea, and mark in this,

How little that which thou denieſt me is;

It ſucked me firſt, and now ſucks thee,

And in this flea our two bloods mingled be;

Thou know’ſt that this cannot be ſaid

A ſin, nor ſhame, nor loſſ of maidenhead,

Yet this enjoys before it woo,

And pampered ſwells with one blood made of two,

And this, alas, is more than we would do.

Oh ſtay, three lives in one flea ſpare,

Where we almoſt, nay more than married are.

This flea is you and I, and this

Our marriage bed, and marriage temple is;

Though parents grudge, and you, w’are met,

And cloiſtered in theſe living walls of jet.

Though uſe make you apt to kill me,

Let not to that, ſelf-murder added be,

And ſacrilege, three ſins in killing three.

Cruel and sudden, haſt thou ſince

Purpled thy nail, in blood of innocence?

Wherein could this flea guilty be,

Except in that drop which it ſucked from thee?

Yet thou triumph’ſt, and ſay’ſt that thou

Find’ſt not thy ſelf, nor me the weaker now;

’Tis true; then learn how falſe, fears be:

Juſt so much honor, when thou yield’ſt to me,

Will waſte, as this flea’s death took life from thee.

(first published 1633)

In this poem as a conversation, a plea, as irony, as life, I heard Donne challenge convention and, as Mum recited it, his mischievousness was transported to the sex and language debates of the ’60s and ’70s. In this poem he has wit, a brilliant metaphor, defiance and over-the-top drama, a situation I related to, because that’s how I’d been brought up – men only want one thing and whatever it takes (even death or torture, according to the saints) you remain a virgin. The poem is argumentative, and like the patriarchal attitudes which were being challenged as I grew up, it’s rather desperate. I hear the pomposity of middle-aged men determined to have their own way and below the humour I see the reality of life for young women, pressured into having sex. I was all too familiar with his desperation, frustration and sarcasm. Even when she’s won – stood her ground, crushed the flea – he doesn’t stop: that’s what her virginity is worth, a flea’s life, a smudge of blood. Other than the genius of the poem, what I also rate it for now is its ability to travel – Donne’s acknowledgment of the girl’s smirk. I can still hear Mum quoting it, her books on the table, a green bank of woods through the window. Sexual liberation and who it benefited was one of the battlegrounds of the decade I grew up in. The Catholics revered virginity so much they even spun a story about a virgin birth. My teacher (the one who scorned my book choices) discussing Angelo’s deal in Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure (if Isabella has sex with him, he’ll release her brother Claudio from prison) asked us, ‘What would you do?’ ‘Sleep with him of course,’ we answered. Next day she told us she was afraid for our souls. Stylistically, the poem’s rhyming couplets are still so familiar, so adaptable and energetic, as is its urgent address to ‘thee’, the lover. We recognise its rhythms, ‘This flea is you and I, and this / Our marriage bed …’ as our own. It is pure performance, the poem has a mike in its hand and a wide stage.

Sister Short was one of the few nuns to teach us without Catholicism interrupting. I did my rote learning of Shakespeare to the rhythm of a treadle sewing machine in her needlework classes. So to a soundtrack of The Temptations’ ‘Just My Imagination (Running Away With Me)’, Janis Joplin’s ‘Me and Bobby McGee’, and Sly and the Family Stone’s ‘Family Affair’, my head was filling up with Shakespeare’s iambic pentameter, Chaucer, Wordsworth and the sung Latin Mass. At that Mass I absorbed the call and response, invocation, the magic of three, penitence, the mystery of the chant – Kyrie Eleison – the commandments, the sound of prayers recited communally, the alchemy that existed in music and words.

Then there was Sylvia Plath. I was eight when she died on 11th February 1963 but she was still a contemporary voice when six years on I began to be aware of her work. I lent out my teenage copy of her novel The Bell Jar too many times and it never returned and her poetry was essential reading for a literate white English girl in the 1960s and 1970s. I had no idea what I was missing as other American women poets documented the civil rights movement. The appeal of Plath’s poetry was the psychological territory she waved as a flag. I read Plath in the same way I strained to understand Leonard Cohen’s lyrics. Did my friends and I whisper the words to ‘Daddy’ in the corridors, thrilled by her courage? We saw the 10 couplets of ‘Edge’, the three hard ‘ah’s of that final line. She was more dangerous than tragic to us at that age. I’d come back to her time and again – I didn’t know it then, but she became one of the poets who’d focus me when I was floundering with my own writing.

But it’s salutary to reflect I had no idea as a teenager about the Black Arts movement and poets Sonia Sanchez, Nikki Giovanni, Audre Lorde, June Jordan and Gwendolyn Brooks. Plath became an icon because she was a woman. It would take me longer to read these Black women poets. And I know things are changing, but it still underlines for me how important it is to ask, what, and who, am I missing?

Reading Plath was markedly different to reading Rumer Godden’s The Greengage Summer. It was one of the novels I most loved in my teens but I read her and then forgot about her. Although The Greengage Summer was sheer pleasure, it frightened me. Misery was expected of a Catholic, not happiness. Three decades later I began to buy every book of Godden’s I came across in charity shops. I found novels printed on wartime paper. I realised why I associated The Greengage Summer with pleasure – her prose reads like poetry. Godden was a writer who paid attention, who was brave enough to concentrate on the domestic music of a house. I needed writers to speak to me in my own voice, we all do. Just as DNA is unique, so is what brings each of us to writing.

A poem I missed at the time I was first reading Plath deals head on with the canon and what it shows me now is the power of the myth of the Romantic creative, suffering for art without a dishcloth in sight. Plath aside, who did write about blackberrying and potatoes, nevertheless appealed because of her rebellion and initially, to me, her dangerous ideas. Elma Mitchell, in this poem, is addressing domestic politics at their grimiest and most visceral, setting ‘him’ against ‘me’ in the first two lines and women as ‘they’, an amorphous other, a group that’s not what it seems.

Thoughts after Ruskin

by Elma Mitchell

Women reminded him of lilies and roses.

Me they remind rather of blood and soap,

Armed with a warm rag, assaulting noses,

Ears, neck, mouth and all the secret places:

Armed with a sharp knife, cutting up liver,

Holding hearts to bleed under a running tap,

Gutting and stuffing, pickling and preserving,

Scalding, blanching, broiling, pulverising,

– All the terrible chemistry of their kitchens.

Their distant husbands lean across mahogany

And delicately manipulate the market,

While safe at home, the tender and gentle

Are killing tiny mice, dead snap by the neck,

Asphyxiating flies, evicting spiders,

Scrubbing, scouring aloud, disturbing cupboards,

Committing things to dustbins, twisting, wringing,

Wrists red and knuckles white and fingers puckered,

Pulpy, tepid. Steering screaming cleaners

Around the snags of furniture, they straighten

And haul out sheets from under the incontinent

And heavy old, stoop to importunate young,

Tugging, folding, tucking, zipping, buttoning,

Spooning in food, encouraging excretion,

Mopping up vomit, stabbing cloth with needles,

Contorting wool around their knitting needles,

Creating snug and comfy on their needles.

Their huge hands! their everywhere eyes! their voices

Raised to convey across the hullabaloo,

Their massive thighs and breasts dispensing comfort,

Their bloody passages and hairy crannies,

Their wombs that pocket a man upside down!

And when all’s over, off with overalls,

Quickly consulting clocks, they go upstairs,

Sit and sigh a little, brushing hair,

And somehow find, in mirrors, colours, odours,

Their essences of lilies and of roses.

from People Etcetera: New and Selected Poems (Peterloo Poets, 1987)

Ruth Padel1 has drawn attention to the fact that Mitchell had no women poets as role models when she began writing. This poem, first published in 1967, is a description of combat – a woman against a hostile regime of domestic demands. In lists of gerunds she underscores woman’s relentless physical activity, the violent impact caring has on her body, her impact on the material world, the bodily fluids she has to deal with. The repetition of ‘needles’ three times is a curse and a promise that drives us to the womb. The poem details a mid-20th century English woman’s daily duties and sets them against the same era’s image and expectations of a middle class wife. Mitchell’s women may be jugglers (they have to be chemists, surgeons, torturers, assassins) but ultimately they’re reduced to gynaecology. This poem triumphs in its own language. The idea of the woman’s role is a platform, but its conceit, beginning with such opposing perceptions of women, is to disrupt and disturb. The poem’s extended third stanza gives the descriptions it contains an epic quality. In this stanza Mitchell focuses on the body, all that women do, their surroundings, a woman’s inherent and permanent state of transgression. The form of the poem helps us understand how these grotesque warriors have come into being – from the first suggestion of ‘blood and soap’ to the short stanza exploring in more detail the ‘terrible chemistry of their kitchens’ we are led into hostile territory, shown giants with mythical qualities who never get tired, capable of overwhelming a man. In the final stanza Mitchell delivers an equally mythical metamorphosis, using the same pair of floral scents as in the combative first stanza, picking up the strategically placed nouns, soap and odours to close the circle.

Decades on from Mitchell, another poet who celebrates domestic life is Alison Brackenbury, whose careful eye in this poem explores loss and what we take for granted. I go to Brackenbury’s poems for delicacy and quietness. These qualities give her language a different kind of vigour and tautness that come from attention to detail.

Lapwings

by Alison Brackenbury

They were everywhere. No. Just God or smoke

is that. They were the backdrop to the road,

my parents’ home, the heavy winter fields

from which they flashed and kindled and uprode

the air in dozens. I ignored them all.

“What are they?” “Oh – peewits –” Then a hare flowed,

bounded the furrows. Marriage. Child. I roamed

round other farms. I only knew them gone

when, out of a sad winter, one returned.

I heard the high mocked cry “Pee – wit,” so long

cut dead. I watched it buckle from vast air

to lure hawks from its chicks. That time had gone.

Gravely, the parents bobbed their strip of stubble.

How had I let this green and purple pass?

Fringed, plumed heads (full name, the crested plover)

fluttered. So crowned cranes stalk Kenyan grass.

Then their one child, their anxious care, came running,

squeaked along each furrow, dauntless, daft.

Did I once know the story of their lives,

do they migrate from Spain? or coasts’ cold run?

And I forgot their massive arcs of wing.

When their raw cries swept over, my head spun

with all the brilliance of their black and white

as though you cracked the dark and found the sun.

from Then (Carcanet, 2013)

The rhymes and half rhymes in threes at the end of the second line of each couplet, and the couplets themselves, are typical of Brackenbury’s understated writing. I like couplets for the space they produce on the page and the energy they generate, moving the reading of the poem on. A couplet, as we know from the ghazal, contains its own elements of a story or language, insights and thought. Brackenbury joins the thoughts and images with rhyme. These sounds are a thread and the music she makes plays steadily, goes deep. She doesn’t make a big deal of her metaphors but uses them confidently. Between she observes, questions, revisits, explores the nature of uncertainty and memory. All this is so human and right that, long before the final, stunning line, she has engaged the heart, and with that image it is possible to breathe out again. How brave, she is, though, to introduce the word God in the first line, in the same breath as smoke and that word we use so casually, ‘everywhere’. Hear how it chimes with air and then hare, this assonance emphasising a development in the idea, placing the poet’s eye more precisely. In these words she moves from sky to ground and a single hare, far more significant because of its mythical status and its associations with fertility. These associations feed those single-word biographical notes, ‘Marriage. Child.’ so that nothing more is needed there. And so I begin to realise how much else is going on beyond the conventions of the line and single narrative. I’m fascinated by the ends of lines eight, 10 and 12, which read “gone/long/gone”, the way other line endings like “run/spun/sun” contain their own condensed tune. I wonder if reading in this way is fanciful, but it also alerts me to the fact that the experienced poet composes on many levels, producing facets of meaning and sound from their skill with words, releasing them from conventional syntax.

On one level, Brackenbury’s language is clipped, mimicking how you might summarise a life impatiently to get to the important bit, which is the sad winter. All the emotional weight of that season, that crucial time, is carried by the memory of the bird, no longer a massive flock, but a vulnerable and isolated creature, under attack, anxious, daft. The insight the poem explores in its final two stanzas goes so deeply into the memory that the ‘everywhere’ of the first line expands into a glorious image and the address in the final line with its suggestion of divine power, reminds us of that earlier childish question, ‘What are they?’

Anyone who’s seen Brackenbury read her work will know how careful she is, how attentive to the audience. What she gives her readers is sheer dedication to the craft and exquisite detail. What’s also critical about her work, and this poem is proof, is its attention to the natural world. Brackenbury is marking the decline of this once-common bird: ‘How had I let this green and purple pass?’ and watching ‘their one child, their anxious care …’. The poem is mourning the lapwing flock she paid no attention to as a child, a bird awarded Red List conservation status. Brackenbury, born in 1953, is a poet I’ve come to read and admire much later in my writing life and it’s the precision of her language that has drawn me to her work, as well as its deep connection to the natural world.

Brackenbury’s first collection, Dreams of Power, came out in 1981, a time when UK poetry publishing was undergoing massive change. A year earlier, Linton Kwesi Johnson published Inglan is a Bitch, but the old guard was keeping firm control of the reins through prizes and positions. Brackenbury is an example of a poet who’s kept her nerve for decades, continuing to publish while balancing work and family and who was one of the women who added promise to the 1980s, the decade I began to write. I can’t change the fact that Brackenbury wasn’t on my radar then but I can be thankful for her persistence and the poems she’s writing now.

Building a Personal Canon

Time, change and chance have all played a role in the writers I now include in a personal canon. There are also individual poems – what place do they have? And what drives my collecting? Is it as random as the books I pick up in charity shops and is that just as valid as any other system? In May 2010, I read about a woman who at the age of 90 – an apparently “unknown” American poet – won the Ruth Lilly Award. Eleanor Ross Taylor’s work was out of print. Clearly she wasn’t unknown, she’d been in the world a very long time. Adrienne Rich wrote that Taylor’s poems ‘speak of the underground life of women … coping, hoarding, preserving, observing, keeping up appearances, seeing through the myths and hypocrisies, nursing the sick, conspiring with sister-women, possessed of a will to survive and to see others survive.’2 I’m reassured when I read women writing about women like this, affirming our right to explore our own existence. I used to think I had to overturn all of that, I dismissed it as a lifestyle I didn’t want. But there are so many aspects to being a girl or woman that we have no choice over. True to this, Ross Taylor’s poem, ‘Woman as Artist’, begins:

I’m mother.

I hunt alone.

There is no bone

Too dry for me, mother …

from Captive Voices: New and Selected Poems 1960–2008 (Louisiana State Press, 2009)

When I began writing I was troubled by the notion of an objective and single canon, and it was still being pushed as a standard of quality. It manifested itself in lists of white men. It set me up for feeling I’d failed – not academic enough, not well read enough, not clever enough … I didn’t understand all the classical allusions, didn’t know enough about form or grammar. The (so-called) giants of literature (often European) don’t trip off my tongue. Thankfully, reading convinced me a canon is personal, not learned, and I hold it like a mix and match – poets whose work I know deeply, poets I’ve come across through recommendation. Some will be part of my life forever and some won’t stay very long. Reading keeps me humble and looking, it keeps me questioning how I perceive the world and reminds me there are different perspectives. The critical and contemporary word is a lens – a reminder to be aware of ways of seeing.

Common sense tells me if I only read titles selected by judges or teachers I’m a fool. It tells me to be wary of trends. So I take recommendations from friends, I actively search and I trust my emotional response. Often I don’t know why I love a poem. Some poems keep giving each time I read them, some need me to do research, and some need a few months, or years, before I rediscover them and read them differently, in another context. Some offer a transient sense of surprise, provoke a question, move me on somewhere else, provide consolation or relief that this writer’s expressed what I’m going through. Even poems that are least successful build a framework for others that endure, where everything falls into place – language, subject, imagery, pace, form.

The work of Carol Ann Duffy arrived quickly on my bookshelf with its bizarre stories of modern life. It’s difficult, so many years on, to remember the impact of her early poems. The first book I bought was Selling Manhattan. As I read it again, I realise her poems showed me a new landscape, a liberation from the self I believed I was under an obligation to expose. Duffy opened up the possibilities of being another person, of stepping into character. Her control of the stanza and the line gave us English drama, passion and politics. ‘Warming her pearls’ was the first lesbian love poem I’d knowingly read. The year Selling Manhattan came out was the year of Black Monday, the Wall Street Crash, and within the collection the poem ‘Money Talks’ still resonates in its chilling, unapologetic viciousness. It pre-dates the film, The Wolf of Wall Street by more than two decades, but when I read it now, that’s what I think of. Juggling registers, quoting the Bible, ‘Money Talks’ presents an assortment of depravity and human exploitation from gambling to arms dealing, cosmetic surgery and violence. What I loved in Selling Manhattan