8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

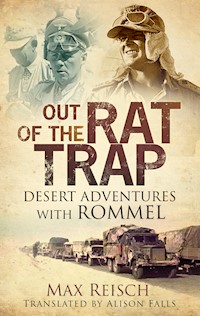

For the Austrian Max Reisch, pioneer international motorist and writer of the 1930s, the Second World War offers yet more opportunities for adventure. Here is his lively account of his time with a vehicle maintenance unit of Rommel's legendary Afrikakorps in Libya, Egypt and Tunisia. On forays into the desert at the wheel of a captured Jeep, searching out wrecked vehicles for spare parts, he visits the fabulous oasis of Siwa and digs his way out of the sinister minefield of Minqar Qaim. Seeing German defeat as inevitable, Reisch hatches several escape plans and finally, with no experience of the sea, acquires a dilapidated fishing boat and some rudimentary navigation skills. He avoids capture at Tunis and, despite damage to the boat, sets sail for Sicily together with seven comrades (and one small dog). Running the blockade of Allied warships and weathering a sudden storm, his motley crew succeeds against the odds. Out of the Rat Trap is a rare and fascinating insight into the Afrikakorps and an entertaining account of a daring escape from the Allies in the Western Desert.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Special thanks are due to the Reisch family for this book, and especially to Peter Reisch for providing many previously unpublished photographs from his father’s collection.

I thank my brother Roger Bibbings, whose interest in motorcycle travel led him to ask me to translate Indien – lockende Ferne, and whose familiarity with the internal combustion engine has helped to make sense of several passages in this story and make them comprehensible to the English reader.

My husband, Nigel Falls, presented me with a scarce copy of Mausefalle Afrika and patiently answered all my history questions on the Second World War.

Horst Christoph, Max Reisch’s biographer, helped me to understand more of the background and was kind enough to discuss some problems of living with the Nazi past. My thanks go to Bob Thompson, an expert in computer graphics, for scanning maps at a moment’s notice, and to all those fans of a younger Max Reisch who wondered what happened to him when he was drawn into Hitler’s war. Here, at least, is part of the story.

CONTENTS

Title

Acknowledgements

1. How this Book was Written

2. Escape or Captivity?

3. The Gateway to Egypt

4. Conversations under Canvas

5. The Sahara Plan

6. Treasure Trove

7. Cleopatra’s Bath

8. The Great Find

9. Driving Feats on the Via Balbia

10. Respite in Tunis

11. An Engineer turns Sea Captain

12. A Slight Misunderstanding

13. Learning the Hard Way

14. Preparations

15. Spanners in the Works

16. The Final Hours in Africa

17. The First Night at Sea

18. Man Overboard!

19. The Lonely Lighthouse

Epilogue

Plates

About the Author

Copyright

1

HOW THIS BOOK WAS WRITTEN

I spent the first days of peace in a shepherd’s hut, high up in the mountains of northern Italy. It was a heady feeling, knowing that the war was over, but now the uproar was at an end, I felt oppressed – not only by the silence of the mountains but by the uncertainty of what was happening in the outside world.

A week went by. Although I had been very frugal, the provisions I had lugged up with me in the rucksack were all gone. I had not been able to carry very much, as my right leg was still not properly mended from the wound I had got at Nettuno.

Meanwhile the Italian peasant who owned the hut had found me out. He was neither friendly nor unfriendly, but I promised him money if he would bring me food. After a few days, during which I ate almost nothing, he arrived with bread and cheese, but we could not agree a price. His demands were excessive and since I was obliged to husband my meagre resources, we haggled for a long time. Being in a tight corner, I found myself at a distinct disadvantage, so I said I would be willing to work for him.

‘No, no, certainly not!’

He was anxious about this as it was apparently illegal. All I could do was sit in my sheepfold and go hungry.

This was a pretty dire sort of existence, not unlike Robinson Crusoe’s. In my childhood I had often longed for such a life and later on I had lived in similar conditions, but that was somewhere in Central Asia where there was no alternative. Here, on the other hand, all I had to do was descend 2,000m into the valley and the throb of civilisation and its comforts would be all around me.

When the peasant brought me a frying pan I felt I could live like a king, since up to that time I had been cooking in tin cans.

There was enough water around, but I had run out of soap. My wardrobe had a pitiful aspect and my shoes were worn through. Things could have been worse, for summer was on its way, but worst of all was the boredom. Now and then I glimpsed an aircraft in the sky, but my only human contact was with the peasant and his little 10-year-old daughter. They were both so wretched and poverty-stricken that I thought they probably lived in a sheepfold too, 1,000m further down the hill – 1,000m nearer to civilisation and yet just as far removed from it as I was.

In my solitude I began to write. I wrote about my two years in Africa, just the way it happened, and got it off my chest. The peasant had no idea why I needed so much paper. If I had told him that I was working on a diary or writing a book, he would probably have regarded me with the utmost suspicion and wondered what sort of top brass he had got hidden away. My presence in his sheepfold irked him enough as it was.

And so this book was written – on newspaper, on wrapping paper, in the margins of an old farming calendar and in minuscule script in my notebook.

I was hungry and, whenever I wrote about the good life we’d led in Tunis or the delicious stuff we’d looted in Tobruk, my mouth would water. Perhaps this was the reason why I wrote more often and at greater length about food than good form would dictate.

The peasant brought me what I needed, including flour, cooking fat and onions, but only for money, at an exorbitant price. I could see that he was as poor as a church mouse himself, and that as long as I had money he would make me welcome. He wasn’t a bad fellow really, or he would simply have robbed me and turned me in.

So I carried on writing and my belly carried on rumbling. I cooked up amazing damper and soups in the frying pan and it all got digested. I have never been a good cook but my innards will put up with quite a lot. Once in Baluchistan I acquired a few eggs from one of the nomads. Not having any fat to fry them, I poured some oil out of the motorcycle and soon they were sputtering nicely. They didn’t taste at all bad but the consequences were devastating. Every few kilometres I had to make an emergency stop in the middle of the desert, leap off the machine and disappear hastily behind the non-existent bushes.

Ah, those were the days, but many years had passed since then.

I often thought about my comrades-in-arms who were now all in prison camps. They weren’t getting much grub either, it’s true, but they had each other, a bit of company and entertainment, even if it was only a worn-out pack of cards. In spite of their troubles, someone could always make a joke and the others would laugh. I never laughed in my sheepfold, in fact I scarcely spoke a word in all those months.

The peasant, or his little girl, came every week or ten days and brought whatever it was we had bargained for on the last occasion. I was on such short rations that I was getting thinner all the time. In the purse around my neck I had only a few hundred lire left.

Often I came very close to climbing down into the valley and giving myself up to the first Allied soldier I met: ‘Arrest me, please, please just arrest me!’ It would be a great relief, so it seemed, to let someone else take on the problem of keeping me alive. It would be great to be in a prison camp, together with comrades. Things were not so hard if you were all together. But was it possible to write a book in such circumstances, and write it the way I wanted? In theory it was, but in practice it wouldn’t have worked.

I had now been living in my hut for seventy days. The money was gone. I offered my camera, but the peasant shook his head. What use was it to him? It was easier to talk him into taking my watch, although he already had one of his own. However, it was impossible to persuade him that the stopwatch function made it extremely valuable and I made it over to him for a derisory sum.

Now I had no watch, but I was writing and I had food for a couple more weeks. In spite of this I went on getting thinner and the lordly names I bestowed on the dishes I cooked could not disguise their meagre content.

I spent hours peering down into the valley, wondering when they were going to come and get me. This could have happened any time, any day, because in the end it was no use relying on the peasant. For me it would have been a happy release, as the constant insecurity was a terrible burden, and uncertainty about the fate of my homeland was wearing me down.

What if I just …?

But except for outward appearances, my situation would in principle have been unaltered, so I stayed in my sheepfold and wrote. I left out the ‘monstrous anger of the guns’ and did not concern myself with high strategy. However, on the fringes of history there are still to be found those countless human stories of personal experience, of adventure, of care and woe, which are all worth recording. All these episodes, both comic and serious, which reflected the lives of 100,000 white men in the heat of the desert (in short, our day-to-day existence in Africa) might prove more riveting than any of the more sensational events of the war. It was in this vein that I preferred to tell my story of Africa and the two years I spent there, including the eventful 47,000km I spent racing through the desert in a Ford, with the driver Froschauer, between El Alamein and Tunis. I would also give an account of how we planned our escape from Africa to Europe, what went wrong and how we finally succeeded.

***

In the end I gave the peasant my rucksack as well, and a threadbare shirt, but by then I had finished writing down my experiences and my reflections. Five months had gone by, the autumn winds were sweeping over the alpine meadows and the first snows were lying on the summits of Adamello.

As I rolled up the multifarious scraps of paper that formed my manuscript, I could not help smiling at the tatty old bundle, but I shoved it under my arm and slung the frying pan over my shoulder. My other possessions fitted comfortably into the pockets of my fraying jacket and I set off down the hill. I gave the pan to the peasant and thanked him for everything. Once down in the village I handed my strange roll of paper into the safe-keeping of the local priest and set off along the village street feeling cheerful and free at last. A lot of traffic was passing and these were Allied vehicles – Americans. So I did exactly what I’d seen people do in the States. When I was over there I had often given lifts to tramps. They would stand on the side of the road hitch-hiking with a casual wave of the thumb over the shoulder.

At last one stopped. It was a Jeep.

‘To the nearest “concentration camp”’, I said in English, as if it were the most natural thing in the world.

‘Where do you want to go?’

‘To prisoner-of-war camp!’

‘I’m not going that way!’

And with that, the Jeep drove off leaving me alone and dejected on the roadside. After a few more attempts I finally struck lucky with a more understanding driver.

In the camp I made such a pathetic impression that they put me straight into the field hospital where I lay for several days while I was subjected to repeated interrogations. After that I got some peace. I had time to gather my wits in a friendly atmosphere and I got three meals a day. Through a big clear window I could view the world in full colour. A new life seemed to beckon.

Eventually they came back and told me I was being discharged – not just from the hospital but absolutely. I could stay on for a few days if I wanted, but I went. In my pocket were my discharge papers and a ticket home, which was wonderful.

It was all I could have asked for.

***

Six years later I felt that the time had come to return to the area and look up the kindly priest. Understandably, he did not recognise me at first, but after we had talked for a while about the time in question, he handed over my bundle, tied up exactly as it was when I had entrusted it to him.

It was with some eagerness and also, I have to say, some curiosity that I looked through the pages I had scribbled six years earlier in my sheepfold, looking out over the Adamello Mountains. Friends advised me to change this or leave out that, but in the end I couldn’t bear to. Even people’s names are still the real ones. All the same, the manuscript lay untouched for another eleven years. One day, on a whim, I gave it to a publisher – and here it is.

2

ESCAPE OR CAPTIVITY?

It usually sounds ridiculous when somebody insists that, way back in the past, he always knew about something or other. It is easy to be wise after the event. However, I can say with certainty that America’s entry into the war in December 1941 made a deep impression on me. I had been in the United States just before the war and the American Automobile Association had made it possible for me to visit all the most important automobile works and those of various key industries as well. This meant that I had some idea of what people over there were capable of producing.

On that historic day at our camp in Derna I made a few observations on this point and on the possible implications for the African theatre of war. I remember it particularly well because my remarks earned me a severe reprimand from my senior officer at the time.

Major Lüdecke, as he was wont to do in special circumstances, had ordered the radio to be brought out of the command post tent and we were sitting or standing around the set under the awning, discussing the new situation. ‘Pearl Harbor a sea of flame, American Pacific Fleet destroyed’ and suchlike was coming out of the loudspeaker.

‘Splendid!’ said somebody.

‘Not surprising’ I muttered.

‘What do you mean?’

‘I just meant, well, the attacker has the advantage.’

‘Of course they do. That’s war. You can’t be sentimental.’

‘You’re right there,’ I said, seeming to agree, ‘because this will be the start of an almighty struggle. The destruction of Pearl Harbor doesn’t mean the destruction of America. This is just a wake-up call over there and now they’re going to be turning out aircraft like hot cakes, not to mention tanks and …’

‘My dear Reisch,’ interrupted the major in his slow, oily drawl, ‘it’s not going to be like that. What you’re saying is a load of rubbish.’ Then, in sharper tones, he proceeded to give me a public dressing-down, larded with references to the Axis Powers, weapons stocks, discipline and the faith which moves mountains.

I listened patiently to the whole thing and realised that I had just made an enemy for life. It could have been worse, as he was due to be relieved of duty shortly on health grounds. A colonel had been designated as his successor, with whom I might get on better. Meanwhile I drew my own conclusions. From this moment I was sure that it was in North Africa that the Americans would launch their offensive against Fortress Europe. It would be a sort of dress rehearsal and serve as a springboard to the continent. We in Libya would be first in line, and what then?

I passed many a night in my tent through the summer heat and the winter rains mulling over this strategy in general, and my own personal fate in particular, both during and after the African campaign. How would it all turn out? What would the future bring? What were the possibilities, especially in the event of defeat? There were essentially four:

1. Going on leave at the right moment. This would be an exceptional bit of luck, assuming there was any leave. In Africa we only dared mention it in whispers, especially if one was as healthy as I was, and unmarried.

2. Being sent home sick or wounded. Sickness was virtually out of the question, as I knew from experience. The subtropical climate suited me very well. (In fact, I never had a day’s illness throughout the whole African campaign). I had often irritated my comrades with references to the ‘glorious Mediterranean climate’ in our theatre of war, as they never really came to terms with the heat. Of course, anyone could be wounded, that was just fate, but with a bit of luck you might get off with a black eye or something, although not enough to get you sent home.

3. Escape. This was easy to say but not so easy to do, considering the situation in which we found ourselves. It meant either crossing the Mediterranean or a dangerous journey over the desert and through many countries. Which of these routes we chose would depend on the area of North Africa in which defeat occurred.

4. Captivity. I had no qualms about this. We were fighting mainly Britons and Americans whose homeland I knew well and whose language I spoke fluently. With these advantages I could reckon on quite tolerable living conditions. Better than that, in spite of being behind barbed wire, I would get to see a bit more of the world and it would be a stimulating experience from which I could gain some useful knowledge. Also, to be frank, I would be out of all danger. Not just the danger of an escape but all the other risks of war would be at an end. All very nice and I would be sure to see home again.

But when? That was the big question mark, the great unknown. It might last for years and years. It might last a decade if the First World War was anything to go by. Could I put up with that, indeed should I, especially when I knew what it would mean to people waiting at home? It was this that finally swayed my decision.

Escape it had to be. Once I had taken this decision (after mature consideration) I never wavered for an instant. As the months went by, it became ever more firmly entrenched in my thinking and planning, until the thought crystallised; after nearly two years in Africa without any leave, I simply had to get home, even if I died in the attempt.

3

THE GATEWAY TO EGYPT

In the autumn of 1942 we were camped before El Alamein. Our spirits were high: the field kitchen was well-stocked with plunder from the British camps at Tobruk and Marsa, and there was a never-ending supply of water for washing and drinking as the Tommies had forgotten to shut off the pipeline they had built for 200km through the desert from Alexandria to El Daba. Besides, this was the gateway to Egypt. Each of us carried a map of the land of the Pharaohs in his pocket and made great play with it. Our interpreter was kept busy providing the most detailed information. It was not easy for him, as he found the German language heavy going, and no wonder. He had been born and brought up in Cairo, and had always spoken French and Arabic, his German citizenship being only incidental. However, chance was enough to turn a curly-headed Egyptian into a German guide. Clothing makes the man, and our man looked very much the part.

We gave the poor chap a terrible time, forever asking which offered the better accommodation – Shepheard’s Hotel or the Mena House? After so long fighting in the desert we were out to treat ourselves, given half a chance.

I also got certain useful bits of information from ‘Georgy’. He was a black African from Mauritius, 24 years old, small and powerfully built. He was also a devout catholic and a stamp collector (which on Mauritius is probably just the decent thing to be).

Georgy had been a soldier of His Britannic Majesty but had not taken it more seriously than was absolutely necessary. This resulted in my effortless capture of him at Tobruk. He was timid to begin with, as one might expect from an African islander, and he crossed himself whenever I spoke to him. He soon realised that I had no intention of shooting him. I appointed him my personal orderly, which pleased him greatly, and in this way we got on very well together. He killed the flies in my tent and helped out sometimes in the kitchen. He had had the pleasure of British military training in Egypt, after which he was stationed there for quite a while, so he knew all sorts of things. He wasn’t stupid, just an incredibly lazy devil. When we stopped to camp, for example, one of his duties was to squeeze out about 2cm of toothpaste on to my toothbrush, but he could never be bothered with more than 1cm – that’s how lazy he was.

As time went on, the things I learned in the course of innocent conversations with Georgy were potentially extremely useful. I wasn’t just thinking of the whisky and soda at the Mena House but also of the Nile Delta. There was always the possibility that our entire army would succumb to a watery death in those thousands of streams and river channels. For a year and a half we had been used to fighting in the desert, but how would we manage in the totally different conditions of the Nile Delta? A number of strategists feared an ultimate catastrophe if the keenly desired breakthrough at El Alamein succeeded, and what then? How would I get out of a mess like that and get back home? The only possible route seemed to be overland through Turkey and the chances were slim. However, if I could only get to Palestine it would be all right. I had some good Arab friends there from my previous journeys who would help me on my way.

With typical thoroughness, the army map stores were provided with all the maps of Palestine, Syria and Iraq. These excellent military survey sheets covered everything as far as Baghdad and Ankara. Nothing had been left to chance: on the general staff they seemed to imagine that we of the Afrikakorps were going to rendezvous with troops from the Caucasus in some Persian oasis.

From the sergeant at the map stores I acquired all the sheets covering Palestine and Syria on a scale of 1:200,000. I slunk off to my tent with this rather hefty bundle and went to work with scissors and paste. I cut off all the white edges and superfluous desert areas. I constructed strips showing the coastal areas of Palestine and Syria as far as the Turkish border, until I had something that was easy to manage. I pored over these maps by night and made my own plans. Nobody suspected what I was doing and nobody would have understood. They were all dead set on the wonderland of Egypt and not least the delights of Cairo, which was scarcely surprising after so many thousands of kilometres through the desert, and so much sand and sun.

In the end it all turned out differently. The largest ship in the world, the Queen Mary, landed 8,000 fresh British troops at Suez in the nick of time, and then we took a frightful pounding. Our interpreter resumed his oriental taciturnity, people stopped talking about whisky and soda at the Mena House and were happy to get hold of a bit of aniseed brandy from the Itaker (as we called the Italians) to counteract the salty taste of the coffee, as there was no more decent water from the British pipeline. I burned my maps of the promised lands. I had my work cut out anyway.

I had technical responsibility for about 900 motor vehicles and these were retreating over a distance of 1,800km. It was probably the longest motorised retreat of all time. I dashed up and down the Via Balbia like a sheepdog, trying to keep the vehicles together and bringing or sending help. Quite often I had to give the order to salvage material and destroy what was left. The three big Boma breakdown trucks, which were my invention and the pride of my commanding officer (CO), were busy day and night. Sometimes it needed only a little help from one of these to bring a physically or mentally shattered comrade back from the brink and so save the vehicle and its load.

This retreat from the outskirts of Alexandria back to Tripoli took a month and a half. Although much weakened we were not beaten. Nowhere had Tommy been able to overtake us or surround us. It’s hard to understand why not. He had plenty of motor fuel, whereas we often couldn’t get back any further because we’d run out of juice. He had nothing but rough-terrain vehicles (we were green with envy), whereas we had only a few of these.

Perhaps he didn’t care. His victory in Africa was assured. When the Americans landed in Algeria, the threat came from two directions. The end was now just a question of time. Once again the problem of escape or captivity reared its head.

4

CONVERSATIONS UNDER CANVAS

They called us the triumvirate. All three of us were alte Afrikaner (old Africa hands), our friendship cemented by hundreds of experiences great and small, comic and serious, to say nothing of the dangers of war which we had survived together. There was Wolfgang Mayr, Helmuth Baumann and me. The first was a Bavarian, the second was from Baden and the third was an Austrian. To begin with we didn’t exactly get on, which is often the case with neighbours, but we had the most glorious arguments.

The most popular member of the team was Mayr. He could swear and curse so fluently that even the rawest recruit, try as he might, could not stifle a grin. Mayr had a go at me too once. It was just after he had been transferred to us from Russia. We had a bet on whether he could call me names for a whole minute without repeating himself.

‘Piece of cake’ he declared with his usual spirit, ‘how much is it worth?’

A good question, as we were all on our beam ends. The dribble of wine or schnapps that occasionally came our way from the army stores was our common property and kept in reserve for celebrations such as birthdays or promotions. It certainly wasn’t for betting. As for money, in the first place, it wasn’t the sort of stake we felt comfortable with and in the second, it seemed pretty pointless to us. Money only makes sense if there is something to spend it on, which in our case scarcely ever happened. We were out in the desert, far from any civilisation, Arab or otherwise – ‘civilisation’ for us meant only the opportunity of buying eggs or dates.

We decided therefore on 20l of water. At that time, the precious liquid had to be fetched from 240km away by truck, and was consequently very strictly rationed. A full Kanister (‘jerry can’ as the British dubbed it), was a valuable possession, and nobody but an old Afrikaner knows just how glorious it can feel to be able to slosh it all over yourself once in a while. This, then, was the stake.

So it was ready, steady, go – and Mayr was off. In one hand he held a watch, gesticulating wildly with the other, while I was subjected to the full force of his graphic Bavarian repertoire. Things went well to begin with, but a minute is a long time, a lot longer than you’d think. The usual army epithets were soon used up and then came the choice titbits: ‘Sie halber Zwilling, Sie kümmerlicher Zwerg. Sie Volksausgabe, Sie Zivilist, Sie darwinische Kreatur, Sie Eintopfgericht!’ (i.e., half-twin, shrunken dwarf, cheap edition, civilian, Darwinian ape, mess of pottage), and much more in the same vein. I was keeping an eye on my own watch and the minute was far from over. With ten seconds to go, Mayr began to falter. ‘You … you…you ...’ he spluttered, gulping for words and turning red as a turkeycock. Then illumination struck and at the very last second he bellowed triumphantly, ‘Sie Kriegsverwaltungsrat!’ (war administration advisor!) He flopped down on his camp bed as the sixty seconds were up and all of us doubled over with laughter.

Mayr had won and there was no question about it, since the title ‘war administration advisor’ was so ridiculous that it required a supreme effort of will on the part of officers and other ranks alike to take it seriously. It seemed to fall naturally into the category of insult. With good reason, these people were also dubbed ‘war prolongation advisors’ (Kriegsverlängerungsräte) - and in fact I was one of them.

That was Mayr all over. He was always forthright, not only in word but in deed. The first time his path crossed that of our commanding officer he was dirty and tired and wearing a thick winter coat, having just arrived from the Eastern Front.

‘You saw some action over there, I suppose? Something to show for it, no doubt?’ By this, the ‘Old Man’ meant medals and decorations and he sketched an enquiring movement with his thumb diagonally just below the second jacket button.

‘Yes, I got that one.’

‘Hrrumph. Very glad to hear it. I need men who’ve proved themselves.’

The boss set great store by medals and was very proud of his recently awarded Iron Cross (Second Class).

‘It was no big deal,’ put in Mayr, ‘and I got this one too, not long after.’ So saying, he made the sign of a large cross with his thumb on the left side of his chest.

The ‘Old Man’ didn’t say much after that, in fact the interview came to an end, because it is tricky when a man has more decorations than his superior officer.

Baumann was a very different sort. In civilian life he had quite a senior job in industry and he was matter-of-fact, cool, reflective and cautious. He was our adjutant and together with the commander held sway over the weal and woe of the men. On him depended the question of leave (within the bounds of possibility), although it is worth noting that he never went on leave himself in spite of a burning desire to do so. No one among us had so many photographs of his family circle as Baumann did, or talked so often of his wife and daughters, and no one was so desperate to get home as he was.

On this score the three of us were in agreement: capture was not an option. Since our retreat from El Alamein to Tripoli, we were at last able to talk about it. In the evening we would often sit in Baumann’s tent by the light of the petrol lamp. On one such occasion he volunteered the observation, ‘The Americans are pressing hard on Tunis. I don’t like it.’

‘Yes. It’s all right for those guys – they’ve got weapons, vehicles, petrol, men, plenty of everything,’ I acknowledged, ‘and in that order. With us it’s the other way round: men first, then more men and weapons and ammunition last of all. If we had any, of course …’

‘Himmelherrgottsakrament! Kruzitürken! Damn it all!’ burst in Mayr in Bavarian, and was soon in full flood. ‘It’s a bloody rat-trap and it’s shut tight as hell!’

Baumann shook his head slowly and thoughtfully.

‘It stands to reason. You’ve only got to look at the map. To the east you’ve got the Tommies, to the north the sea, to the west the Yanks and to the south the desert. Where are we? Right in the middle, in a nutcracker. We’re coming to the crunch. Prost!’

In silence we savoured a shot of Sarti, the Italian cognac which we had wrested with a deal of cunning from an encampment of the Italian catering corps. Thank heavens we didn’t manage this too often, as it was foul-tasting stuff. It can’t have been real Sarti and there were persistent rumours that bottles of this rotgut were changing hands in Naples for 50 centesimi each. However, it was in short supply and therefore seemed good, and it cheered us up. In the absence of glasses we used the indicator bulbs from petrol filters. Of course, this was misuse of army property and thus strictly prohibited but it permitted a slight improvement in the taste of the Sarti.

Outside it was cold and windy. The tent’s guy ropes rattled in the winter ghibli. It was shortly before Christmas in 1942 and we were camped 20km east of Tripoli in an orange grove. The tents were tucked under the trees and covered with brushwood as camouflage against air reconnaissance. American fighter planes were becoming more noticeable and even landlubbers like us began to feel the way the wind blew.

Baumann looked thoughtful as he pumped up the pressure in the petrol lamp. The stark white light shone all around us and threw grotesque shadows on the walls of the tent.

‘No, it doesn’t look good on the map, but that’s not what really matters’ he said, sounding more optimistic (or was it ironic?).

‘Do you think we’ve turned stupid or what?’ exclaimed Mayr furiously, ‘because I haven’t! You sound like the joke about the peasant and the globe. You probably know it, but it bears retelling. A peasant is visiting the city and while he’s there he sees a globe of the world for the first time. His friend explains it to him. ‘You see here where all this green is? That’s Russia, and the red, that’s England with its colonies and dominions. The blue is America. And this dot in the middle here is – Germany!’ The peasant takes it all in, rubs his chin, scratches behind his ear and then asks innocently, ‘Do you think Hitler knows that?’.’

‘Of course I’ve heard it, but you’re right,’ said Baumann, ‘and it describes just how things are going to be for us in Africa, and soon.’

What were we going to do? There had to be an answer. We didn’t want to be prisoners, so what it came down to was where was the nearest friendly country? Sicily. It might just be possible to get there, but in between lay Malta, a maelstrom of activity. Nasty.