Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Elsinor Verlag

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Deutsch

The title of this volume, "Outlook and Insight", is deliberately evocative of Koestler's "Insight and Outlook" (1949), an investigation of the similarities he found among and within art, science, and social ethics. In this study of Koestler through his early novel "The Gladiators", his particular interest in revolutions via "The Law of Detours" is the focus of Outlook (Part 1). Those reflections are explored in ten segments, one of which is Koestler's own unpublished summary of the first half of "The Gladiators". The volume closes with an account of the attempt to film "The Gladiators" in the late 1950s, including the recent publication of that thwarted project's unproduced screenplay. Additional Insight (Part 2) may be gained from reading the first full publication of the newly discovered correspondence generated by Edith Simon's agreement to translate Koestler's now-published MS of "Der Sklavenkrieg". A Postscript presents a representative selection of Edith Simon's sketches of characters in "The Gladiators".

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 257

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Outlook & Insight

New Research and Reflections on Arthur Koestler’s The Gladiators

by

Henry Innes MacAdam

Arthur Koestler’s response to a note from William Plomer, former editor at Jonathan Cape, Ltd. when Koestler submitted the MS of The Gladiators (Wm. Plomer Collection Durham Universithy GB033 PLO Letter # 117)

DEDICATION

To my family, friends, and colleagueswho encouraged the researchand writing of this book.

Omnia mala exempla ex rebus bonis orta sunt(“All destructive examples arise from positive origins”)

Livy, Bellum Catilinae 51.25-27 (spoken by Julius Caesar)

Hatred is the most accessible and comprehensive of all theunifying agents …

Mass movements can rise and spread without belief in a god,but never without belief in a devil.

Eric Hoffer, The True Believer (1951)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Frontispiece

Acknowledgements

Preface

Introduction

Part I: Outlook

Koestler at a Crossroad

Revolutionary Detours:

Koestler’s Summary of The Gladiators Books 1 & 2

Commentary on Koestler’s Summary of Books 1 & 2

Two Similar Revolutionary Detours

Koestler and British Literature of the 1930s

Koestler’s Earliest Plays: Twilight Bar and Bucco the Peasant

From Brecht to Wilder: Literary Influences on The Gladiators

Structural Differences: Editorial Modifications

Table of Contents: Der Sklavenkrieg vs The Gladiators

Theme Quotations: Aristophanes and Silvio Pellico

Some Aspects of The Gladiators’ Narrative

The Gladiators: An Unproduced Screenplay

The Thwarted Project to Film The Gladiators

Conclusion

Part II: Insight

Literary Collaborators: Liebe Edith … Herzlichst, Dein Koestler

Correspondence in the Edith Simon Archive

Transcription, Translation, and Commentary

Conclusion

Addendum 1: Koestler’s Spartacus as “Gaeta”

Addendum 2: Koestler and the Editors at Jonathan Cape

Appendix 1: Arthur Koestler Timeline (1936-1941)

General Outline

Specific Dates/Events/Places

Appendix 2: Koestler-Simon Correspondence: Scans of Original Documents

Postscript

Illustrating The Gladiators:Edith Simon’s “Translation Sketches”

Bibliography (Sources for the Timeline; General Bibliography)

The Author

On this Book

Acknowledgements

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Those who helped to make this volume a reality deserve separate recognition here, though all are thanked at the appropriate place(s) in the text or notes. Gordon MacAdam, Tom Sayers, and Dori Seider read very early drafts of what became Part I; Scott Perry and Matthias Weßel did the same for Part II. Duncan Cooper read portions of both parts, while at the same time co-authored our large study of the effort to make a movie of Arthur Koestler’s The Gladiators in the late 1950s. My debt to Howard Gaskill is particularly large, because he undertook a complete renovation of my preliminary work on Part II, and then agreed to a critical reading to Part I. Thomas Pago at Elsinor Verlag was not only an early champion of publishing this volume, but allowed it to change shape and length several times during its nearly two years of development.

Numerous individuals and institutions facilitated my research into various aspects of Koestler’s life and his publications, especially but not exclusively focused on that portion of his career in which The Gladiators came into being as a work of fiction, and twenty years later when it nearly made it to the Big Screen as a Hollywood epic film. The family of Edith Simon, especially her late sister Inge Simon Goodwin, and Edith’s daughter Antonia Reeve, provided personal insights and recollections. Antonia alerted me to the Edith Simon Archive, the personal papers and artwork of her mother that, in 2015, were donated to the National Library of Scotland. The NLS archive staff were most helpful in obtaining scans of the Koestler-Simon correspondence generated by their shared translation work on The Gladiators, and which are the central feature of Part II of this volume. The staff of the Edinburgh University Library, wherein the Koestler Archive is housed, helped me track down personal and business correspondence of Koestler. That was equally true of the staff at the Harry Ransom Center of the University of Texas at Austin, where the papers of Koestler’s literary agent A.D. Peters are now archived.

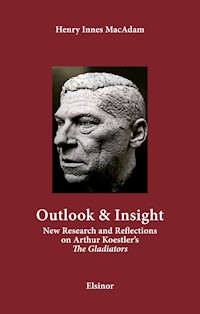

Permission to publish correspondence, and excerpts from Koestler’s fiction and non-fiction, has been granted by the Koestler Estate/Peters-Fraser-Dunlop, Ltd. in London. Permission to publish Simon’s correspondence, and a selection of her unpublished sketches of character in The Gladiators, is granted by the Edith Simon Studio in Edinburgh (via Antonia Reeve). Michael Scammell and Matthias Weßel have been generous in their assistance and enthusiasm in seeing this volume completed. Paul Henrion has generously provided the front cover photo of the terra cotta head of Koestler, and the photo of the bronze likeness made from it displayed on the inside front flap of this book. The bronze head is in the National Portrait Gallery (London, UK), and the photo is from that institution’s website (public domain). The photo of the terra cotta head was taken by Chris Dawson, with my thanks. Paul Henrion has also kindly allowed publication of the letter from Daphne Hardy to Edith Simon written in 1939.

The terra-cotta bust of Arthur Koestler (cover) is a creation by Daphne Hardy Henrion (1917-2003). It is reproduced here with the kind permission of her son, Paul Henrion.

Every effort has been made to secure other publication permissions needed.

PREFACE

My interest in Arthur Koestler’s The Gladiators began by sheer chance, when I was given a copy of the 1954 paperback edition as payment for helping a friend “excavate” his living quarters on a family farm/boarding house in upstate New York. It was the summer of 1955, and during the week of my thirteenth birthday, that area of the USA was assaulted by two successive Atlantic Ocean hurricanes, a most unusual occurrence. When I had walked home from Forest Farm, I realized I had left the “gift” novel with my friend, and walked back the half-mile in rain and wind to retrieve it. It was worth the wet evening walk. I stayed awake most of that night reading about the greatest of the three Servile Wars that threatened the Roman Republic, the Spartacus Revolt that closed out the first third of the first century BC. It was heavy reading for my age, but nevertheless compelling. I wondered who was the “Edith Simon” credited with translating The Gladiators, and also puzzled about the language from which it had been translated, since nothing was said about it. The front and back cover images were lively.

I had just seen, in color and CinemaScope, the MGM epic Demetrius and the Gladiators (1954), the popular sequel to The Robe (1953). During the summer of 1956 (again by chance), I read a paperback reprint of the Thames Williamson novel The Gladiator (1948). Arena combat was popular fare in 1950s Hollywood, especially those tales conveniently set in the Christian era. Koestler’s novel was firmly set in the pre-Christian Roman world, not during the reign of a mad Caligula or a paranoid Nero. Thus it was somewhat surprising to learn that another novel, Howard Fast’s Spartacus (1951) actually made it to the Big Screen in 1960. I had no idea then, or for almost another two decades, that the Kirk Douglas epic movie had beaten out a better-financed, better-scripted, and provisionally well-designated cast on its own turbulent trajectory toward production. Not until I had read Bruce Cook’s biography Dalton Trumbo (1977) did I note that The Gladiators had been sold in 1957 to Yul Brynner’s Alciona Productions for filming in late 1958, and its projected budget of $5 million (almost $45 million now), and planned distribution, were guaranteed by United Artists. No director, or screenwriter, was mentioned.

That prompted me to write to Koestler (among others) with questions about the production. He replied laconically:

All I can remember is that some twenty years ago [1958] an American producer obtained an option on The Gladiators, but subsequently dropped the project when he discovered that another big American producer intended to make a film based on Howard Fast’s novel Spartacus.1

That it had been a worthy endeavor, and one that might be completed in the future, was expressed in a reply from Kirk Douglas, to whom I’d also written: “I do have great admiration for Koestler’s book, and feel that it would have, and still would, make a wonderful movie.”2 It was not until Koestler’s death in 1983, and the publication of his co-authored autobiography Stranger on the Square (1984), that I learned of his purchase of, and brief residence on, Island Farm near Stockton, New Jersey on the Delaware River (see “Koestler at a Crossroad” below for details of that). The connection between that interlude, and my reading of The Gladiators, was the double-hurricane occurrence of August 1955: while I retrieved the novel during the storm, the Delaware River reached severe flood levels 100 miles to the south. Island Farm was swept away in that once-in-a-century deluge. Koestler had sold it only the year before. The link between that weather-driven event and the impact of his novel on me had been forged, even though it was coincidental. By the time I learned of it, I already knew that coincidence had been of great interest to Koestler. And by then, the mid-1980s, I had read all of Koestler’s fiction and some of his non-fiction, especially the books focused on science and human behavior.

The centenary of Koestler’s birth encouraged me to write about the impact The Gladiators had on my interest in Roman antiquity. A teaching career centered on archaeology and classical studies had some of its roots in that novel, and once more my interest turned to the name of its translator, Edith Simon. By the time I made contact with her daughter Antonia Reeve, and Edith’s sister Inge Simon Goodwin, Edith had been dead for a few years. While I was in the process of editing two of her unpublished essays, Michael Scammell’s biography of Koestler revealed that the German MS of The Gladiators survived in Moscow after WWII. A few years later, I found and purchased a copy of Abraham Polonsky’s forgotten screenplay for the attempt to film The Gladiators. The pace quickened five years later when Simon’s cache of “translation correspondence” with Koestler, and the MS of Der Sklavenkrieg, were made available for reading. What follows in the volume below is a direct result of that. Its appearance, in conjunction with Elsinor Verlag’s publication of Der Sklavenkrieg, is another manifestation of Coincidence.

1Koestler to MacAdam, 21 June 1978.

2Douglas to MacAdam 14 July 1978.

INTRODUCTION

All the German original manuscripts of each of Arthur Koestler’s first two published novels (The Gladiators, 1939; Darkness at Noon, 1940) were lost during WWII. A single, mostly complete, typescript of each was recently recovered, allowing for the first time a comparison with their initial English translation, for eighty years the basis of all other translations. Access to one or more German MSS of Arthur Koestler’s first two novels offers not just a chance to assess the author as a writer of German fiction, but also to appreciate the quality of the initial English translations of The Gladiators and Darkness at Noon.3 The second of those two considerations is central to this book focused on The Gladiators. Very little was known until recently about the process by which Der Sklavenkrieg (The Slave War), the working title given the novel by Koestler, became The Gladiators. This was so not only because the MS of the original could not be consulted, but also because nothing was known about the role of the novel’s translator, Edith Simon, during the time she worked for Koestler. In several recent publications I have had the opportunity to explore the process by which the novel was simultaneously written and translated, and to publish original sketches created by the translator.4

It is possible now to begin an overdue evaluation of this complex and carefully crafted historical novel. Full publication of the German original with commentary is expected in late 2021, and following that may be a new English translation. The latter will, if done, offer readers detailed comparison with Simon’s original, which until now was the basis of translations into all other languages. We may anticipate renewed and important studies of Koestler as novelist on the basis of the two works of fiction for which he is best known.5 To that end, I have chosen two aspects of The Gladiators that I believe are worthy of separate attention during the process to bring the full text of the novel into print. One is to examine a recurring theme — what Koestler called “The Law of Detours” — that runs through all three of Koestler’s earliest published novels.6 The other is to document the translation of The Gladiators through a small cache of unpublished correspondence (“Liebe Edith … Dein Koestler”) now archived in the National Library of Scotland (Edinburgh). Related to those two is a Postscript that spotlights in more detail the creation by Simon of two dozen sketches of characters in the novel. These were not intended for publication, but were sent to Koestler as a “completion gift” to him when The Gladiators was finally submitted for publication in the summer of 1938.

Arthur Koestler twice provided an account of when, where, why, and how he began the process of researching and writing The Gladiators (1939). The first is in a chapter (“Excursion into the First Century B.C.) in the second volume of his autobiography, The Invisible Writing, published in 1954.7 The second dates to just over a decade later, as a “Postscript” to the Danube Edition of The Gladiators (1965).8 The ‘Postscript’ could stand on its own as Koestler’s explanation for The Gladiators, since a portion of it was either paraphrased or copied verbatim from the longer account in The Invisible Writing. Nevertheless the Postscript omits much that refers to Koestler’s research and writing techniques and models, and some of the earlier account that reflects upon his remembrance of the political motivations for choosing the subject of that novel. Koestler biographies give more attention to the earlier of the two accounts because it is more comprehensive. In the pages that follow, both are consulted for purposes of comparison and contrast.

The title of this volume, Outlook and Insight, is deliberately evocative of Koestler’s Insight and Outlook (first published in 1949), an investigation of the similarities he found among and within art, science, and social ethics. But instead of oppositional tensions or compare/contrast dichotomies he wrote about in earlier or later investigations, i. e. “ends” vs “means”, “yogi” vs “commissar”, “promise” vs “fulfillment”, “lotus” vs “robot”, etc., Insight and Outlook was his first non-fiction attempt to find a “unifying theory” linking those three major manifestations of human creativity. The tension inherent therein was the knowledge that human creativity also had a destructive component capable of negating all of the positive achievements. Koestler coined the term bisociative in highlighting this dichotomy. In the present study, Koestler’s lifelong concern with that dilemma, manifested in “The Law of Detours”, will be the focus, directly or indirectly, of his thinking during the late 1930s as seen through the prism of The Gladiators itself, and the correspondence its translation generated. Hopefully, the studies presented here concerned with Koestler’s inclusive Outlook should provide readers with some additional Insight. A further reflection, on Edith Simon’s unpublished sketches of characters in The Gladiators, closes out the volume.

3Sonnenfinsternis was published in 2018 by Elsinor Verlag, Germany, and a new English translation by Philip Boehm followed in September 2019 (Scribner’s, USA; Vintage, UK).

4“From Der Sklavenkrieg to The Gladiators: Reflections on Edith Simon’s Translation of Arthur Koestler’s Novel,” International Journal of English Studies 17.1 (2017): 37-59; “Illustrating The Gladiators: Edith Simon’s Lost Sketches for Arthur Koestler’s Spartacus Novel” (Part 1), Roman Archaeology Group Magazine Vol. 12.1 (May 2017) 10-13; Part 2. RAG 12.2 (Nov. 2017) 11-15.

5See Zénó Vernyik (ed.), Arthur Koestler’s Fiction and the Genre of the Novel: Rubashov and Beyond (Lanham, MD; Lexington Books, 2021). Sonnenfinsternis is acknowledged therein.

6Arrival and Departure (1943) was the third book of this trilogy, and the first novel Koestler wrote in English.

7References here are from that chapter in the USA Danube Edition (Macmillan, 1969) 319-327.

8The complete text is from the USA Danube Edition (Macmillan, 1965) 316-319.

Arthur Koestler, age 45, in 1950 (Rene Saint Paul/RDA/Everett Collection)

Part I

Outlook

Just as there is no historical inevitability,there are always historical alternatives.9

KOESTLER AT A CROSSROAD

On 6 October 1950 Arthur Koestler purchased, at an auction in central New Jersey, a working farm on an island in the Delaware River. He had bid for it sight unseen (photo only) while visiting friends in the area.10 The purchase was emblematic of Koestler’s lifelong pattern of establishing residences that were suitable just long enough for him to lose interest in them, and move on to another location.11 He owned Island Farm for five years, but lived there intermittently only during 1951-52.12 His age (45) at the time of purchase is significant. Twenty-five years earlier (1925-26), he had voluntarily withdrawn from enrollment at an engineering school in Vienna, and began a decade-long career as a journalist that morphed into writing novels and non-fiction. Twenty-five years after (1975-76) buying his island retreat in the USA, he was at the end of his productive literary career. By then his oeuvre included — besides six novels — works on the history of science, a successful polemic against the death penalty in the UK, studies of extrasensory perception, an investigations of chance and coincidence in human affairs, and a controversial volume on religion and ethnic identity (The Thirteenth Tribe, 1976). Thus in 1950, when the world was at mid-century with a very uncertain future as the Cold War unfolded, Koestler was (although he could not have known it) at the mid-point of his own adult life. It was a cross-road moment, promising detours and sometimes dead ends, already a steady pattern in his career.

Koestler biographies, or Koestler critiques that are biographical in nature, go back as far as the 1950s.13 Only the two most recently published (David Cesarani, The Homeless Mind, 1998; Michael Scammell, The Indispensable Intellectual, 2011) had access to the documents at the Arthur Koestler Archive at Edinburgh University, but not to the small correspondence collection now in the Edith Simon Archive at the National Library of Scotland. At long last we have one Koestler biography that is both concise and comprehensive, quite a feat given the mass of material now available. Edward Saunders’ Arthur Koestler14 fills a long-standing need for those readers who require a compact introduction to, rather than a lengthy journey through, Koestler’s lifetime of creative conflicts and causes. As Saunders aptly puts it, “He was an often pitch-perfect and incisive commentator on twentieth-century life, with a remarkable talent for literary autobiography”.15 Though this new biography is worthy of a full review,16 it is noted here only as a reminder of Koestler’s legacy as a provocateur intellectuel and a signal that interest in his writings is more intense than ever. Saunders’ assessment of Koestler’s fiction is not that book’s strong point; see now on this Vernyik (2021).

Nevertheless, Saunders does draw attention to one important characteristic of Koestler’s earliest published fiction:17 his insistence that all revolutions fail, sooner or later, because of irreconcilable tensions generated by the participants’ reaction to the unfolding uncertainties that inevitably occur during such events.18 The inability of revolutionary movements to avert or resolve those conflicts of interest is what Koestler termed “The Law of Detours.” As we’ll see, he clearly confronted that concept is his earliest published novel The Gladiators (1939), and continued it in the two novels that followed, Darkness at Noon (1940) and Arrival and Departure (1943): “The Gladiators is the first novel of a trilogy … whose leitmotif is the central question of revolutionary ethics and of political ethics in general: the question whether, or to what extent, the end justifies the means.”19

When those three novels were under consideration for re-publication in the late 1950s, Koestler emphasized the Law of Detours (without calling it such) in a letter of 9 August 1958 to his literary agent in London. At the time of writing, The Gladiators project was in early film pre-production for expected release in 1959:

… [Swiss publisher Rudolph Streit-]Scherz says that he is willing ‘to republish within a reasonable period four or five of [my] most important novels and volumes of essays’, and asks for suggestions. Here they are. Novels: The Gladiators, Darkness at Noon, Arrival and Departure. These three form thematically a trilogy on the self-defeating nature of revolutions, on violence in the service of an ideal. You may point out that The Gladiators is going to be filmed next year with Yul Brynner, etc. which will add to its topical value.20

Koestler himself was well aware of his emphasis on that failure of purpose among revolutionaries, although such a view can’t be linked to the many “detours” he experienced from 1925 until his death almost sixty years later.21 Saunders is hardly the first critic or biographer to point that out. The film rights for The Gladiators had been sold to Hollywood in early 1957, and a year later blacklisted screenwriter and director Abraham Polonsky was hired to adapt the novel for a big-screen epic then being planned. Polonsky’s script reveals clearly where the writer (who had joined the American Communist Party [CPUSA] in the 1930s) agreed with Koestler and where he did not. As Duncan Cooper notes: “I think Abe’s idea, like Koestler’s, was to de-mythologize Spartacus: power corrupts not only because of, but in spite of. The Law of Detours is pitiless. I suspect that every new revolution has to use violence to suppress its own inconvenient Left (or Right) wing after it has arrived in power: Lenin and Kronstadt, Stalin and Trotsky, Mao and the Cultural Revolution, Castro and the moderate democratic forces against Batista, Deng and the Gang of Four, and later yet, the dissidents in Tiananmen Square.”22 In a personal communication to me, Howard Gaskill observed that the Law of Detours was a concept within European thought long before Koestler:

“It doesn’t owe anything to Kepler, does it? I’m reminded of [Friedrich] Hölderlin’s “exzentrische Bahn” – that the shortest distance between two points needn’t be a straight line is a thought fundamental to [Gotthold] Lessing’s Erziehung des Menschengeschlechts and Hegelian dialectics, and therefore Marxism too?”23

Thus we may explore this topic, knowing that the Law of Detours has a past history; Koestler was inclined to see within it a decidedly deterministic future.

9Stephen F. Cohen, Bukharin and The Bolshevik Revolution (1989) xv.

10Arthur & Cynthia Koestler, Stranger on the Square 98-100. The price was US $41,000, which in today’s USA dollar value would be $410,000 for a working farm on an island of 112 acres.

11He and wife Mamaine Paget were then living in Paris. He eventually bought a flat in London, on Montpelier Square, which became his permanent home — the first long-term residence since he left his family home in Vienna in 1925. It is the titular locale of Stranger on the Square.

12During that sojourn he completed writing, and read the proofs for, Arrow in the Blue (1952), and then began composing the sequel volume of his autobiography, The Invisible Writing (1954).

13His six autobiographical works, begun during WW II (Scum of the Earth, 1941) and ending with the posthumous co-authored volume contributed to by his third wife Cynthia (Stranger on the Square, 1984) cover the years from his birth until 1956, before his creative career peaked.

14Critical Lives Series (London, Reaktion Books, 2017). The book’s single major drawback is its inexcusable lack of an Index. Saunders, inevitably, did not benefit from correspondence in the Edith Simon Archive.

15Saunders, Koestler, 19.

16My review appeared in Journal of Modern Jewish Studies 17.3 (October 2018) 519-520.

17His novel Die Erlebnisse des Genossen Piepvogel was not published until 2013 — see below.

18Koestler 53-56. Oddly, Saunders fails to use the term “Law of Detours” in summarizing the plot, especially when identifying the very events that actually force a change of direction for the slave revolt. Unless I have missed it, the term is also not used in Sauders’ discussion of Darkness at Noon or Arrival and Departure (ibid, 63-70). Search may be facilitated via the e-Book edition.

19Arthur Koestler, ‘Postscript’ to the Danube Edition of The Gladiators (1967) 316. In that same Postscript he goes on to say: “It is a hoary problem, but it obsessed me during a decisive period in my life. I am referring to the seven years [1931-38] which I spent as a member of the Communist Party and the years which followed immediately after [1939-1943]” (ibid. 316). The entry on Koestler in The Oxford Encyclopedia of British Literature Vol. 1 (2006) 207 errs in naming the third novel of the trilogy Thieves in the Night (1946). Koestler also refers to “The Law of Detours” as a theme in his early fiction in the second volume of his autobiography (The Invisible Writing, 1954; 1969: 327). Howard Gaskill reminds me that the concept, though not the label he gave it, might be Keplerian in origin (below). Koestler might have discovered it in research on Kepler (begun as a student in Vienna) for his biographical study The Watershed (1960).

20From an unpublished letter by Arthur Koestler, at his summer home in the Austrian Tyrol, to his literary agent John Montgomery in London. A.D. Peters Collection, University of Texas at Austin, Box 43 Folder 7. The planned movie, to be funded and distributed by United Artists, was beaten to the Big Screen by the Kirk Douglas epic film on the same subject, Spartacus (1960). On that cinema rivalry, see MacAdam & Cooper, The Gladiators vs Spartacus Vol. 1 (2020).

21Whether Koestler ever applied “The Law of Detours” to himself is uncertain, though he was aware that the 1950 “crossroad” in his life was important. From this point forward in his career, the focus would be on political non-fiction (though he published one more novel): he turned to scientific biography and social issues in the 1960s, and then to parapsychology as well as ethno-religious identification in the 1970s. His last few publications were collections of earlier essays.

22Cooper (a film historian) in an e-mail to me of 2 September 2016. “Abe” is a reference to Abraham Polonsky (1910-1999). His unproduced script for the attempt to screen The Gladiators is the centerpiece of a just-published two-volume study dedicated to that film project (MacAdam & Cooper, 2020 (Vol. 1); Polonsky, Fiona Radford, Cooper & MacAdam, 2020 (Vol. 2).

23Email to me of 19 November 2020.

REVOLUTIONARY DETOURS

Koestler’ Summary of The Gladiators Books 1 & 2

(First half of his projected Spartacus novel c. 1937)

Revidierte Fassung: Original (Revised Version: Original)24

On the last two pages of this four-page insert (between pp. 244-245 of the German MS) Koestler typed (single-spaced) an “abstract” or “précis” of the first half of his novel (Books 1-2). The first page of Book 3 (The Sun State) follows this insert. Matthias Weßel characterizes Koestler’s summary as a “synopsis” in this note from his Rohtext, 107 pp. of typed transcriptions from handwritten notes, which he has shared with me.25 The translation that follows Weßel’s note is mine:

Drittes Buch; 619-1-6; 148 Dokumente, MS-S. 246–389; [Dok. 1-2 sind aus dem gleichen Papier wie das Inhaltsverzeichnis am Ende des vierten Buchs, weswegen man davon ausgehen kann, dass es sich bei Dok. 1 um das Deckblatt handelt und bei Dok. 2 um einen dem Gesamttext vorangestellten Hinweis, auch wenn sie hier in der Mappe des Dritten Buchs abgeheftet sind. Dok. 3-4 sind eine Synopsis der ersten beiden Bücher; Zweck: unklar.]

Book Three; 619-1-6;Document 148, MS pp. 246-389; [Docs. 1-2 use the same paper as the Table of Contents at the end of the fourth book, which is why one can assume that Doc. 1 is the cover sheet and Doc. 2 is a note relating to the entire text, even if they are filed here in the folder of the third book. Docs. 3-4 are a synopsis of the first two books; purpose: unclear].

As Weßel indicates in his note above, the purpose for this “synopsis” isn’t readily evident — especially so since there is no corresponding summary of the second half of the novel which we would expect to be placed at the end of Book 4. It may be that Koestler felt the need to write this abstract, at the halfway point of his novel, as a selling-point to offer a prospective publisher.26 We know from his own account that the research and writing of Der Sklavenkrieg took four years (1935-1938), with interruptions for journalistic and “hack” work, and once by imprisonment (and threat of execution) during the Spanish Civil War (1936-37).27

His initial plan was for the novel to be published in German, and thus to add a second installment (for Books 3-4) to the abstract when he had completed it. But given the novel’s clearly anti-totalitarian theme, publication would have been impossible anywhere in Germanophone Europe, or in European countries that had German-language print capability, after 1936. Swiss publication was possible, via Emil Oprecht’s Europa Verlag, a press for exiled writers which published Koestler’s Spanisches Testament (1938). Publication of Der Sklavenkrieg in English became a practical possibility when Koestler’s account of the Spanish Civil War (Spanish Testament) was translated into English and published in London at the end of 1937 by Victor Gollancz Ltd. The incomplete abstract of Der Sklavenkrieg that survives may have been translated by Edith Simon, first for Putnams Ltd. (an agreement that went awry), and then for Jonathan Cape’s “Editor’s Reader” William Plomer. On the basis of Plomer’s positive reaction, Koestler was awarded a formal book contract very early in 1938.28