7,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

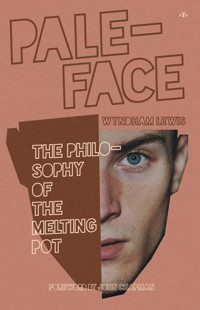

- Herausgeber: Antelope Hill Publishing LLC

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Distinguished and highly original, the irrepressible controversialist Wyndham Lewis (1882–1957) is known for his sharp wit and sardonic insight. Though Lewis was a prolific British author,

Paleface: The Philosophy of the Melting Pot, ringing perhaps a bit too true and nearly prophetic, remains one of his lesser known works, serving as a lively and provocative exposition of racial problems.

Originally published in 1929,

Paleface examines the presence and role of “race-consciousness” in contemporary literature and poetry, providing brilliant commentary on the works of Sherwood Anderson, D. H. Lawrence, Ernest Hemingway, and others. In the work, Lewis contextualizes Western man’s curious modern tendency for self-destruction, particularly in light of the First World War, and considers the “melting pot” model that America aspires to and the resulting amalgamation of the “Palefaces.”

Antelope Hill Publishing is proud to bring

Paleface: The Philosophy of the Melting Pot by Wyndham Lewis back into print, just as relevant today as when it was first penned, complete with a foreword by John Chapman.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Paleface

Paleface

The Philosophy of the Melting Pot

Wyndham Lewis

A N T E L O P EH I L LP U B L I S H I N G

The content of this work is in the public domain.

Foreword Copyright © John Chapman 2024.

First Antelope Hill edition, first printing 2024.

Originally published by Chatto & Windus, London 1929.

Cover art by Swifty.

Edited by Harlan Wallace.

Citations and layout by Margaret Bauer.

Antelope Hill Publishing | antelopehillpublishing.com

Paperback ISBN-13: 979-8-89252-016-4

EPUB ISBN-13: 979-8-89252-017-1

CONTENTS

Foreword by John Chapman

Preface

Part I: A Moral Situation

1. The Future of the Paleface Position

2. If the Redskins Were in Our Position

3. The Ethics at the Basis of the Color Question

4. The Cause of “God and the People”

5. Passing “The Point Beyond Which There Seems No Longer toBe Either Good or Evil”

6. “Every Man Both by Law and Common Sentiment IsRecognized as Having a ‘Suum’”

7. Our World Has Become an Almost Purely Ethical Place

8. Esprit de Peau

9. How You Must Beware of Too Much “Esprit de Peau”

10. The White in the Same Boat as the Black

11. The Paleface, That “Negation of Color,” as Seen by Du Bois

12. The Black, and the Paleface Middle-class Democratic Ideal

13. A German Vision of Black vs. White

14. White Phobia in France

15. The Effect of the Pictures of the White Man’s World Uponthe East

16. Final Objections to Me as “Champion”

Conclusion to Part I

Part II: Paleface or “Love? What Ho! Smelling Strangeness”

Introduction

Section I: Romanticism and Complexes

1. The Paleface Receives the Dubious Present of an“Inferiority Complex”

2. White Hopes with a “Complex”

3. The Opposite “Superiority Complex” Thrust at the SameTime Upon the Unwilling Black

4. The Nature of Mr. Mencken’s Responsibility

5. What Is “Change” or “Progress,” And Are They One orMany?

6. From White Settler to Poor City White

7. Americana of Mencken

8. “Complexes” as Between Whites

9. The American Baby

10. Was Walt Whitman the Father of the American Baby?

11. The Healthy Attitude of the American to His “Babylon”

12. Sherwood Anderson

13. The Essential Romanticism of the Return to the “Savage”and the “Primitive”

14. Possessed by a “Dark Demon”

Section II: The “Inferiority Complex” of the Romantic White,

and Student Suicides

1. Romance on its Last (Physical) Legs

2. The Consciousness of One Branch of Humanity Is the Annihilation of Another Branch

3. When the “Consciousness” or Soul of a Race Is Crushed,the Race Collapses

4. Dr. Berman and the Suicide Epidemic Among the Whitesof the United States

5. Races Similarly Ruined by the White Man

6. Behaviorist “Summer Conversation”

7. Race or Ideas?

Section III: “Love? What Ho! Smelling Strangeness”

1. “We Whites, Creatures of Spirit” (D. H. Lawrence)

2. Mr. Lawrence a Follower of the Bergson–Spengler School

3. Spengler and the “Musical” Consciousness

4. Communism, Feminism, and the Unconscious Found in the Mexican Indian by Mr. Lawrence

5. The Indian a “Dithyrambic Spectator”

6. The Under-Parrot and the Over-Dog

7. Evolution, à la Mexicaine: (Genre Cataclysmique, à laMarx)

8. Race or Class Separation by Means of “Dimension”

9. An Invitation to Suicide Addressed to the White Man

10. “Spring Was Coming on Fast in Southern Indiana”

11. “Torrents of Spring”

12. The Dread of Sexual Impotence

13. The Manner of Mr. Anderson

14. “Brutal Realism” cum the Sophistication of Freud

15. The Black Communism of Anderson

16. “What Ho! Smelling Strangeness”

17. The “Poetic” Indian

18. The Mississippi and the Manufacturers

19. Passages from Poor White

20. The Contradiction Between the CommunistEmotionality of Mr. Anderson and His Impulses toCounter the Machine Age

21. White “Sentimentality”

22. “I Wish I Was a Nigger”

23. “The Kid”

24. The Fantods

25. “Uncas” and the Noble Redskin

26. Machines vs. Men

27. Henry Ford and the “Poor White”

Conclusion to Part II

1. The White Machine and Its Complexes

2. Inferiority, and Withdrawal “Back to Nature”

3. The Revolutionary Rock-drill and the Laws of Time

4. The “Jump” from Noa-Noa to Class War

5. How All Backward Steps Have to Be Represented asForward Steps

6. A Working Definition of the “Sentimental”

7. Every Age Has Been a “Machine Age”

8. What is “The West”?

9. The Intellect “Solidifies”

10. The Necessity for a New Conception of “The West,” andof “The Classical”

11. How the Black and the White Might Live and Let Live

12. The Part Race Has Always Played in Class

13. Black Laughter in Russia

14. White Laughter

A Final Proposal: A Model Melting Pot

Appendix

Bibliography

A P A L E R S H A D E O F W H I T E

A Foreword by John Chapman

No English writer in the twentieth century has proven to be as much of a conundrum as Wyndham Lewis, and its proof lies in the fact that he is often ignored. When one looks at the astounding body of work he produced in his lifetime, in both his writings and his paintings, which were replete with all sorts of satirical attacks and artistic experimentations, it beggars belief that there’s so little to be said about the man compared to others who get so much ink devoted to so little. Part of this silence was his crime of publishing Hitler in 1931, part of it was his constant attacks on contemporaries which embittered the tastemakers, and part of it is that it is fashionable to attack the modernists, both from would-be traditionalists and also eager postmodernists who find massive errors in the modernist visions. And though postmodernism has buried modernism, we are still living with its ghosts, and Lewis haunts us with familiar themes and arguments that resonate all the more strongly now. Jonathan Bowden, in his speech at the 8th New Right Meeting on Lewis, said he “was a great artist, flawed in some ways, but great because he attempted to reach the stars.” If Lewis tried to reach the stars, then perhaps the silence is because we’re still combing through his dust to make sense of the man and his works—works like Paleface: The Philosophy of the Melting Pot.

Wyndham Lewis is a complicated writer and artist, and any work that tries to analyze him or even explain him will find itself discussing his character and his biography ad nauseam due to the reasonable expectation the curious reader may not be familiar with it. He is a writer who many have tried to keep forgotten but who keeps reasserting his shambling zombie corpse because it matters so much more than whatever the flavors of the day are. If you are one of many reading a Wyndham Lewis work for the first time, then briefly:

Wyndham Lewis is not a figure you’ll hear about much except from people who really like Wyndham Lewis. He was both a painter and a writer, though he is probably more known these days for his writings than his paintings. Lewis was in many ways the embodiment of the pan-Anglo experience of the expansive and fungible global empire. Born to an English mother and an American father off the coast of Canada in 1882, he lived a transatlantic identity in the gray zone of nations. He served heroically in the First World War and became an artist who once flirted with fascism and often found himself on the outs of society. He is mostly known for novels like Tarr and Snooty Baronet, but his reputation was permanently damaged by an essentially pro-Hitler work he wrote before Hitler came to power called Hitler. There is so much that Wyndham Lewis had written, however, works largely forgotten, with Paleface being one such work.

Paleface occupies a lesser status in the Lewis canon. His biographer Paul O’Keeffe barely mentions it in his biography of Lewis, Some Sort of Genius, devoting only a few paragraphs to his purpose in writing it and its publishing history, noting at the end “it was not published in the United States during Lewis’s lifetime.”1 Initially it seems the lower status that Paleface has is due to the explicit racial ideas that Lewis is exploring. However, it becomes quickly apparent that there is a niche aspect to Paleface as while Lewis does write some very provocative things about where he sees the position of White and European man in the late 1920s, the work is fundamentally an attack on the “cult of the primitive” and the fashionable ways non-White peoples are written about by contemporary writers, and the philosophy that underpins this direction that Western man had found himself in. Those seeking a polemical diatribe on the differences between the races will be surprised to discover just how much the work is focused on critiquing the works of fellow writers Sherwood Anderson, D.H. Lawrence, and briefly Ernest Hemingway.

That’s what leaves this work with a fascinating legacy. Those who have studied the works of Lewis in its breadth have come away from reading Paleface with wildly different and opposing interpretations of the work. Loathsome Jews and Engulfing Women by Andrea Loewenstein views Paleface as an expanded examination of “the threatened extinction of the white race” that shifted Lewis’ focus “from women and homosexuals to blacks as the feared and hated Other, [paving] the way for Lewis’s next shift—to a racist anti-Semitism in Hitler.”2 By contrast Wyndham Lewis: A Critical Guide says that though it is “far from being a taintless document it cannot be considered as, in any meaningful sense, racist.”3 Katrin Frisch in her work on modernist writers and fascism called The F-Word gives a pretty comprehensive analysis of the hidden complexity in Paleface and why it engenders debate among the few who have read it:

Indeed, Paleface is a dense and complicated text on a sensitive topic, written in Lewis’s customary cynical tone. Yet it would be too easy to stamp it as a simple racist tract, as part of the argument addresses an important issue, which has lost little of its validity. For Paleface discusses white writers who use people of colour as a convenient trope to establish an antidote to white (i.e. modern) civilisation. Thus, while authors such as D. H. Lawrence and Sherwood Anderson celebrate non-white cultures for their freedom from oppressive conventions and romanticise their connection to nature, Lewis, quite rightly, considers these depictions as well as the—at least as he perceived it—widespread obsession with Black culture problematic. So far this argument offers a legitimate critique that is still relevant today, as Terence Hegarthy also observed, when he remarked that ‘it was Lewis who first classified Uncle Tommism’. However, from here Lewis’s argument veers into a form of white supremacy that today might fall under the label of ethnopluralism. Lewis sees the preoccupation with people of colour in literature as well as cultural influences such as jazz (which remained a major target throughout Lewis’s life) as an anti-white agenda. . . . He bemoans the fact that there are no advocates for the Palefaces . . . and he fears that an appreciation of people of colour and their culture would not lead to equality but a reversal of racial power hierarchies. . . . Paleface is a defence of white culture and an attack against harmful primitivism—harmful for the people who are turned into tropes but also harmful for white culture, which gets inundated with anti-white sentiment.4

In some sense, what Paleface represents is a modernist debate between D.H. Lawrence and Wyndham Lewis on the future of White men. Jonathan Bowden captures the essential difference between these men who often had seemingly similar views but had a “standing hostility” to one another and “detested each other.” This might be a bit of an overstatement, as the literary dialogue between the two men was cut short by Lawrence’s untimely death in 1930 after a long illness, and the stormy relationship was largely in the realm of literary criticism punctuated by moments of grudging respect. Bowden’s read on their philosophical difference leading to the writing of Paleface rings true, though. He says “Lawrence is a pagan and a vitalist but in some ways really a perennial heathen and a Traditionalist,” while “Lewis is a violent eruptor of modern discourse.” For Bowden, Lewis believed “that there is a separation between the modern and that which has preceded it . . . that we don’t know absolute truth.” While Lawrence is a kind of anti-modernist progressive who sees the technological and modernist project as something to be survived and that modern man must tap back into the vitalist and primordial aspects of our deepest blood-consciousness, embracing our innermost subjectivity, for Lewis the only way we can work through our inability to understand the absolute truths is through “the possibility of their configuration through struggle, through life, through dialectic, through reordering the energy within matter.” To put simply, Lewis rejected any kind of sentimentality and their various respective cults that tell you to get back to what you were. If Lawrence is Become Who You Are or even Return To Tradition, then Lewis is Create What You Must Become.

There is a small cottage industry in analyzing Lewis’ works and parsing out his intent that has kept his literary reputation at least afloat, but that is not much at play in Paleface despite what the academics might say. Lewis is clear in “Part I: A Moral Situation” about how he views the “Palefaces” of the world and the moral position that the White world has found itself in after the metaphysical destruction that was wrought by the First World War. By any modern definition of the words “racist” and “White supremacist,” this work is both as it commits the unpardonable sin of seeing White people as real, as White people having interests, and seeing the position of White people as a fundamentally moral issue. What throws people off reading it is that from the perspective of someone living in 1929, what Wyndham Lewis is saying in the first part likely came off as absurd as to the average person looking around, as there seemed to be no reason to think there was any demographic threat to White people. In 1929, the population of global White people was somewhere around 26 percent to probably 36 percent, at least one-quarter and maybe as much as one-third of the global population, while Africa was only 7.7 percent of the global population.5 In 2024, by contrast, White people sit in the world population at somewhere probably around 11 percent while Asia and Africa are at 59 percent and 18 percent respectively. For Lewis to be concerned about the plights of the“Palefaces” in 1929 is the true strength of Lewis’ writings as he was always looking toward the future and seeing where things would be, and writing to that audience while attacking his current one. Things he said then would seem bizarre then, but they are positively revolutionary now, such as his warnings to Europe about their little isolated fortress (emphasis mine):

For what our White skin is worth, symbolically or otherwise, it is in America that its destinies are today most clearly foreshadowed: the essential universality of the problems provided for the Palefaces of America by the Indian factor in Latin America, by the Negro in North America and the West Indies, and by the proximity of Asia to the western shores of the United States, makes their attitudes in face of them of some moment to Europeans. And though there is no White man’s burden in Europe at present, the isolation of Europe is rather artificial; and so, politically, even, the questions lightly touched upon in this book are not insignificant. (Preface, pg. xxvii)

It’s not enough however for Lewis to attack the notion of Europe’s isolation as an artificial reality that was never going to be sustainable. Lewis was not unique in that idea as other writers and thinkers of the time period pointed to the same, such as Oswald Spengler who warned in Man and Technics that the racial “adversaries have caught up with their instructors” in the realm of technics and technological domination and that this was “no mere crisis, but the beginning of a catastrophe.”6 The answer to such a catastrophe, and an unavoidable reality that needed to be both confronted and embraced as Lewis saw it, was for the “Palefaces” of Europe to become a melting pot unto themselves, hence the subtitle of Paleface being The Philosophy of the Melting Pot. It was a controversial notion then as it is now when the idea is brought up, this idea of a mixed racially-Aryan imperium (and not a racially mixed imperium) versus the protections of petty nationalism for all nations, no matter how big or small. And that is to say nothing of the controversy of the phrase “melting pot” being coined by an ardent Zionist playwright, Israel Zangwill, and his political reasons for doing so. That Lewis would propose such an idea in 1929, for Europe specifically, at a time when fascism was securing its foothold and National Socialism was on the rise displays his drive toward progressive ideas being a bomb thrown into the ring of conventional politics. Part of his reason for doing so was as a defense of America at a time when a popular form of European nonfiction was “educated and literate European man goes to the United States and is horrified and perplexed by what he sees there,” exemplified by works like Knut Hamsun’s The Cultural Life of Modern America, American Life by Paul de Rousiers, and to a lesser extent D.H. Lawrence’s Studies in Classic American Literature. His nuanced defense of America and his belief that Europe should mix internally as America did is prescient when nearly one hundred years later any discussion on the plight of the White world is riddled with bad faith discussions on answering what is Whiteness down to the molecular level and misguided ironic jokes on the duskiness of other members of the White family. In some of his plainest language in Paleface Lewis lays out his case:

[A] Swiss peasant woman is in character and physical appearance often so identical with a Swedish, English, German, or French girl, that they might be twin sisters. This everyone must have remarked who has ever travelled to those countries. It has always been fratricidal that these people should be taught to disembowel, blind, and poison each other on the score of their quite imaginary “differences” of blood or mind, but today there is less excuse for it than ever before. So why not a melting pot, instead of more and more intensive discouragement of such a fusion? Europe is not so very large: why should it not have one speech like China and acquire one government? (pg. 230)

It’s clear that ten years after the end of the Great War that this veteran of that war viewed that conflict as a catastrophe and potential mortal blow to the “Palefaces” unless an explosively new idea on how to progress the White race took hold. Being a modernist and a mover within the avant-garde art scenes gave Lewis insight into the direction things were being taken culturally. It’s not a coincidence that the term avant-garde means vanguard. What is niche today can take power tomorrow. Fools used to laugh at the culture and terminology that was produced on websites like Tumblr and now they live in fear of it and its canceling power. Paleface can be an astounding book to first read because of how everything that was novel in 1929 can feel so familiar now, one hundred years later. Lewis covers how no other race would engage in the self-castigation that Whites do; he blames the self-castigation on both Christian morality and even Nietzsche (for Nietzsche was known to criticize Germans for their Germanness), the terrible influence of the Jewish publisher Alfred Knopf and his Borzoi Books on liberal and aspirational White people, and all of the impacts that this has on the political scene and what he calls the esprit de peau, or the spirit of skin—that is, race. And in America he knew that this spirit was not present among the educated, despite stereotypes so prevalent about Americans:

The once proud, boastful, super-optimistic American of the United States has become just a White man-in-the-street with a pronounced “inferiority complex.” (I speak of the educated, or book-reading, American.) This fact, or something like it, is patent to anybody who has followed American thought of late and had opportunities of meeting a good many Americans. (pg. 101)

As powerfully relevant as this work is today, the same issues that plagued his book Hitler are as relevant here as they were there. One reason for the mixed reception by later scholars of Lewis is that he leaves enough wiggle room for himself by playing the role of the curious observer who is just asking questions and noticing things without being quite the forceful advocate that he initially promotes himself as. In his defense of White people, rather than being quite vociferously pro-White as one would imagine, he signals a desire for the abolition of all supremacy, which is hard to take seriously given his anti-democratic and elitist sensibilities he constantly promoted in works such as The Lion and the Fox and The Art of Being Ruled. Tyrus Miller notes this aspect of Lewis’ skepticism toward liberal democracy, aswhere “Lewis suggests that for the ‘ruled,’ himself among them, the open exercise of power in fascist and communist countries might be preferable to liberal democracy’s production of consensus through culture.”7 Thus when Lewis writes the following in Paleface, it’s difficult to take him at his word that this is truly what he wants:

That the Whites, on their side, are being given a certain consciousness—this dual process is what I have been discussing: for the colored peoples are urged to develop a consciousness of superiority, and the same book seeks to force upon the Paleface a corresponding sense of inferiority. It is this that is unfortunate: the mere reversal of a superiority—a change in its color, nothing more—rather than its total abolition. (pg. 37)

Lewis’ cautiousness ultimately led to some literary survival for him compared to writers like the entirely forgotten Pierre Drieu La Rochelle, who took himself out as National Socialism was being extinguished, but this attitude and temperament never went unnoticed or uncommented on, and which has led to some of the most scathing criticisms toward an important writer ever written. The American Marxist critic of postmodernism, who is also sometimes lumped in with postmodernism, Fredric Jameson wrote an entire book on Wyndham Lewis entitled Fables of Aggression: Wyndham Lewis, the Modernist as Fascist, which excoriates Lewis for “his sterile and chronic oppositionalism [and] his cranky and passionate mission to repudiate whatever in ‘modern civilization’ seemed to be currently fashionable.” Jameson notes that “Lewis lived a grinding contradiction between his aggressive critical, polemic, and satiric impulses and his unwillingness to identify himself with any determinate class position or ideological commitment.” Finally, in an assessment that would have certainly infuriated Lewis to hear, Jameson writes:

The intellectual authority of the culture critique depends on the repression of this concrete social situation, and on the projection of its anxieties into some more timeless realm of moral judgment: the sense of placelessness, the illusion of absolute values thereby produced, discloses the constitutive idealism of this genre, which formally tends to express a classical conservatism even where its content seems to contradict the form. Lewis was often, in this sense, merely a conservative.8

One imagines Lewis seething at being called a conservative.

This was not only a posthumous reputation. One of the most brutal descriptions of Lewis came from his contemporary Ernest Hemingway who wrote about meeting Lewis in A Moveable Feast.

Wyndham Lewis wore a wide black hat, like a character in the [Latin] quarter, and was dressed like someone out of La Bohème. He had a face that reminded me of a frog, not a bullfrog but just any frog, and Paris was too big a puddle for him. At that time we believed that any writer or painter could wear any clothes he owned and there was no official uniform for the artist; but Lewis wore the uniform of a prewar artist. It was embarrassing to see him. . . . I watched Lewis carefully without seeming to look at him, as you do when you are boxing, and I do not think I had ever seen a nastier-looking man. Some people show evil as a great racehorse shows breeding. They have the dignity of a hard chancre. Lewis did not show evil; he just looked nasty. Walking home I tried to think what he reminded me of and there were various things. They were all medical except toe-jam and that was a slang word. I tried to break his face down and describe it but I could only get the eyes. Under the black hat, when I had first seen them, the eyes had been those of an unsuccessful rapist.9

The tragedy of this for Lewis is that he admired Hemingway in some aspects and saw an ally in him in Paleface. Lewis writes approvingly of his work The Torrents of Spring and the two exchanged letters over this subject. Hemingway even wrote that he enjoyed reading Paleface. Susanna Pavloska recounts these exchanges and the eventual falling out in Modern Primitives:

That Hemingway was amused by the racialist debates going on around him is evident from the echoes of Madison Grant in the subtitle that he gave his satire, The Torrents of Spring: A Romantic Novel in Honor of the Passing of a Great Race. . . . The Torrents of Spring is a blatant parody of Sherwood Anderson’s Dark Laughter. . . . The Torrents of Spring ridicules Anderson’s primitivism on the level of both style and content. Replying to an admiring letter from Lewis, Hemingway wrote: “I am very glad you liked The Torrents of Spring and thought you destroyed the Red and Black Enthusiasm very finely in Paleface. The terrible shit about the nobility of any gent belonging to another race than our own (whatever that is) was worth checking.” The elitist Lewis, who in Paleface had railed against the ascendancy of “people to whom things are done,” clearly sensed an ally in Hemingway. However, when Hemingway continued to produce work in what Lewis labeled his “idiotic” mode, placing his center of consciousness in bemused or inarticulate narrators, Lewis unleashed what many critics to be the most damaging attack ever made on Hemingway’s work. In the “Dumb Ox,” published in the collection Men Without Art, whose title itself mocked Hemingway’s Men Without Women, Lewis emphasized Hemingway’s stylistic debt to Gertrude Stein, another one of his targets, sneered at his lack of political awareness, and quipped that he “invariably invokes a dull-witted, bovine, monosyllabic simpleton . . . [a] lethargic and stuttering dummy . . . a super-innocent, queerly-sensitive village-idiot of a few words and even fewer ideas.” To Lewis, this deliberate divestiture of eloquence was incomprehensible; however a closer look at Hemingway’s ambiguous attitude towards primitivism reveals it to be a complex phenomenon that had ramifications for his entire writing career.10

This might explain why Hemingway described Lewis as an “unsuccessful rapist.”

When reading the personal attacks on Lewis while also being familiar with his work, it can lead to a certain kind of sympathy, because Lewis often seems like a man “unstuck” in time due to his foresight and the way that impacted his life. This is often the fate of Cassandras who see what’s far beyond the horizon into the dark beyond the dark but are cursed to live in time and space. Heidegger, in his philosophical critiques of technology, saw into that dark beyond the dark, too, and came to the conclusion “only a God can save us.” This leads then to territory that feels even more familiar, disturbingly so, that the effect of the shifts he was feeling was for those cognizant of being Palefaces that they were destined to be as outlaws.

But all the natural leaders today in the White world are strictly speaking outlaws. They are in an “abnormal” position. . . . The reason we are outlaws then is that there is no law to which we can appeal, upon which we can rely, or that it is worth our while any longer to interpret, even if we could. We, by birth the natural leaders of the White European, are people of no political or public consequence anymore, quite naturally. We are even repudiated and hated because the law we represent has failed, not being as effective as it should have been or well-thought-out at all, I am afraid; having been foolishly and corruptly administered into the bargain. There is not one of us (except such a venerable and ineffective figure as Shaw, for instance) who is in a position of public eminence; nor will a single one of us, who is worth anything, ever be allowed to attain to such a position. We, the natural leaders in the world we live in, are now private citizens in the fullest sense, and that world is, as far as the administration of its traditional law of life is concerned, leaderless. Under these circumstances, its soul in a generation or so will be extinct, as a separate unit it will cease to exist. It will have merged into a wider system. (pg. 74)

Not only was Lewis ahead of the curve on what would be considered “dissident” politics quicker than anyone would have thought possible, he understood how a race could be destroyed, even in ways that wouldn’t seem plausible at first thought.

I admit, however, that the culture of one race, acquiring a political mastery over another, and imposing its ideas upon it, is able and very likely to destroy the soul and so the physical life of another race. There are too many events that testify to it in recent history for that not to be beyond possibility of question. But an idea is quite as powerful. Even a race, for that matter, can annihilate another race with a swarm of ideas, or intellectualized notions; ideas proper to itself but with properties of disintegration for another race; or with ideas not necessarily its own, but such as it could manipulate without injury to itself, and which are destructive to its adversary. (pg. 146)

Lewis’ understanding of these problems is thanks in great part to having done his foundation work in works like The Art of Being Ruled and Time and Western Man. Lewis had a deeper understanding of what politics is and why they matter better than any of his contemporary artists, which may have led to some of those cautious conservative tendencies as the implications of the insurmountable challenges are bound to make any intelligent person nervous. This is why so few people write about Lewis, even when they are aware of him. This is why most things written about him are very critical. He is extremely challenging, and even when his writing seems casual you have to stop and think about what you want to say.

Shorn of references to writers that would have only mattered to his contemporaries and personalized students of those works, Paleface is a work that demands that you believe serious things and that you take them seriously, even if Lewis cannot help but indulge in his favorite vice of being ironic. Being the transatlantic man that he was and seeing the Palefaces as they were, he saw race as an always internally mixing continuity and that the tragedies of the First World War went far beyond even the people he shared political sympathies with. He rejected any splitting of the Old World from the New, saying “what happens to Europe is of great importance to America, and vice versa—what happens to America, that other Europe, must be of great moment to us.” (pg. 230) He notes that if it had remained intact, we would be all the better for it:

If the White world had kept more to itself and interfered less with other people, it would have remained politically intact, and no one would have molested it; the Negro would still be squatting outside a mud-hut on the banks of the Niger, the Delaware would still be chasing the buffalo. We could have been another China. Such aloofness today, as things have turned out, is an ideal merely, though to me it is not an ideal. I merely put the matter in that light because for the average unenlightened Paleface that would seem much better—he would like to be a powerful boss rather than a cosmopolitan wageslave in the melting pot, and his ideas do not soar above some regional dream. It is always from an exaggeration, however, on one side or the other, that the actual comes into existence. Everything real that has ever happened has come out of a dream, or a utopia. We are the utopia of the amoeba. Many of our lives would seem heaven to the apes. (pg. 216)

This could go on forever. A single paragraph from Paleface can be digested for several more. What’s more important is that this work be read, digested, and not forgotten. There is an important legacy in the works of Wyndham Lewis that must be kept, warts and all. To read a work by Wyndham Lewis is to truly experience literature in a way that is difficult to fully describe, which is why there are still people in academia who endlessly discuss him despite his star being completely collapsed and diminished. The lessons in it are clear, and those looking for a political platform or a polemical to beat their chests on will be sorely disappointed, but Lewis isn’t here to soothe you. He’s here to attack. He’s here to provoke. He’s here to make you think about who and what you are.

The true Paleface knows who he is. Do you?

PREFACE

Part II of this essay was written during a visit to the United States (summer 1927): since its first appearance in Enemy No. 2 it has been somewhat modified and other material has been incorporated in it. The part entitled “A Moral Situation” and the passages coming beneath the heading “A Model Melting Pot” have been written during the last few months, and are published here for the first time.

For what our White skin is worth, symbolically or otherwise, it is in America that its destinies are today most clearly foreshadowed: the essential universality of the problems provided for the Palefaces of America by the Indian factor in Latin America, by the Negro in North America and the West Indies, and by the proximity of Asia to the western shores of the United States, makes their attitudes in face of them of some moment to Europeans. And though there is no White man’s burden in Europe at present, the isolation of Europe is rather artificial; and so, politically, even, the questions lightly touched upon in this book are not insignificant. In other respects, humanly, and artistically, there is an inexhaustible fund of simple amusement in consciousness of pigment. Color is not perhaps so fundamental a thing as form, but it is, beyond dispute, in many respects of more immediate importance to men. Gentlemen prefer blondes, for instance—that was a question of pigment, and what a popular subject it proved! But gentlemen prefer, as far as their own persons are concerned, sunburn and a certain swarthiness. How brunette, however, would the masculine mind suffer gentlemen to become, in a search for the virile?—is it possible for gentlemen to be too “dago” and too “dark”? And then there must be a certain number of blond gentlemen.

But ultimately Whiteness is, in a pigmentary sense, aristocratic, perhaps—the proper color for a gentleman; and Blackness irretrievably proletarian. May not this be an absolute, established in our senses? Then the dispute about cuticles would be seen to be another facet of the general assault upon privilege. Whiteness of skin if, like ermine, it is a symbol of rank, must be suspect to the democrat. The most humble Babbitt possesses something enviable, to which, besides, intellectually and socially, he has no right—namely his pale face. But I need not insist: color is not only controversial, it is for the human being of symbolical importance—it is able to dwarf stature, put intelligence in the shade, challenge quarterings; pallor and divinity are quite possibly in some way associated in our human eyes.

Wyndham Lewis

March 1929

PART IA MORAL SITUATION

1. The Future of the Paleface Position

Now that my essay Paleface is to appear almost intact as part of this book, I hope by what I shall say in the opening pages to make it impossible to misinterpret its drift too much. I have been denounced as a “champion” or “savior,” and that charge I must deal with once and for all, if only to be able to prosecute my function of “impartial observer.” After a couple of years or eighteen months more of intense anti-Paleface propaganda, such champions will in fact arise. That I regard as fairly obvious. A variety of either astute or indignant men (persons actually pale with rage, or else persons reflecting that they might as well get something out of the possession of our traditional hue, since up to the present it has not exactly been an asset) are at this moment, upon that we can depend, preparing to assume that role.

To all these bolivars I wish a prosperous outcome to their spirited endeavors. At first their lot will be a hard one. They will have to idealize us a little, I expect—our pale faces have been so systematically blackened. And it will of course be difficult to prove that the Paleface is better than his Black or Yellow brother, not only because it is not true, but also because it is so unpopular a notion.

My position is that I am ready and most anxious to assist all those who suffer from paleness of complexion and all those under a cloud because their grandfathers exterminated the Redskins, or bought and sold cargoes of Blacks. My sense of what is just suffers when I observe some poor honest little pale-faced three-pound-a-week clerk or mechanic being bullied by the literary Borzoi big-guns of Mr. Knopf, and told to go and kiss the toe of the nearest Negress, and ask her humbly (as befits the pallid and unpigmented) to be his bride. I also am convulsed with a little laughter at the solemnity with which so often these discussions are pursued—the measurements of cranial index, of lip, brain, and eye, in which the Borzoi investigator will indulge, the high scientific plane in short upon which so much of this matter is gushed forth. But there are strict limits to my ability to help, and these I must now define.

Meantime I again publish and foretell that the time will come (and that immediately) when, upon the daily “starred and red-billed” appearance before the footlights of some indignant righteous figure (his face corked to look Black) dispatched by Mr. Knopf or Mr. Mencken or Mr. Plomer to abuse and ridicule the audience (squatting beneath him, pale both with natural pigment and with equally understandable alarm), and to tell them what a lousy lot they are, an extremely pale figure will either arise from among the spectators and dramatically approach the stage, or else will appear out of a trap, or descend from the ceiling, or merely stalk from the wings, and we shall hear what we shall hear.

2. If the Redskins Were in Our Position

This first essay, entitled “A Moral Situation,” is devoted to showing the part played by the puritan morality in the present situation. I do not of course mean that without that harsh, double-faced and double-edged, deeply sentimental code the world scene would not have changed drastically. What I do mean is that the transformation of our society, consequent upon the technical triumphs of science, would have been conducted perhaps in a more rational atmosphere—not, as at present, thick with a medieval gloom of bloodshot righteousness.

Historically, the mischief that resides in unbridled moral righteousness can be described as follows: Having wiped out or subjugated all peoples who had not had the advantages of a Christian training in gentleness, humility, and other-worldliness, the puritan Palefaces of America and Europe naturally were very contrite and tried to make up for it to those who were left. Quantities of edifying books (which were translated into all languages) were produced, pointing out what a beast the Paleface was. There were just a few Palefaces who tried to bluff it out and announced roundly that they were “ blond beasts”—but such sectaries abused both their brother Palefaces and their imported “Pale Galilean” God into the bargain, so that made no difference.

There is no especially sentimental or even misguided movement of emancipation today, anywhere in the world, that the typical Protestant moralist can oppose, on any logical ground. For logically he is committed to every sentimental moral value whatever. I do not of course mean that we should behave like Redskins, but it is not quite pointless to note that were the Redskins where today the Whites are, technically paramount in a mixed population, no “color question” could possibly have arisen. The supreme beauty, significance, and limitless superiority of the copper skin, that of Choctaw or Blackfoot, over skins of all other colors, would be a settled axiom and doctrine: no hint of any other point of view would ever pass the severe red lips of the Red legislators and their fellow Redskins. Also, the Redskin being notoriously taciturn, there would not be much even of that: there would be no need of palaver, of course, whatever. In short, it is conscience that makes cowards, or saints, or just sentimental pinky-pinky little Palefaces of us, that is the truth of the matter: and yet we are as harsh as ever with each other, in business and in private life, and there is some chance that we may wipe each other completely out—where, with the disappearance of the White skin, the color question would automatically cease.

A question is lying in wait for me: “Are you not then upon the side of conscience-you despise the Christian ethic?” But it is to that I wished to lead, and I answer promptly “Oh no—you have quite mistaken my meaning. You expect too much of me, or too little, according to the point of view. The principle of an absolute value in the human person as such, of whatever race or order, I am eager to advance. But you? I only question if you fully understood the nature of your Christian sacrifice. If you do not understand it, then it is useless and you are merely a fool. When a person as it were selfishly immolates himself, in response to some very tawdry emotional appeal, we call it a sentimentality. Are you sure that your asceticism (or humanitarianism, radicalism, or liberalism) is not of that kind?”

If you want to know the answer to these questions of mine, see whether my further analysis outrages or annoys you or not. Then you will know.

3. The Ethics at the Basis of the Color Question

The European political leaders have been almost fantastically sensitive to ethical considerations in their policies from time to time—they have seldom acted too brutally without afterwards acting too gently, to restore the Christian balance. This hypersensitive condition induced by their Protestant Christian training, of church and Sunday-school, has had its good and bad side, in the sequel: but as statesmanship, upon the old jingo basis, it was indefensible.

So having isolated in the present situation in which our society finds itself the principal motive power, that which gives it the color that it has though not the form, we can proceed to an examination of those ethical principles at their source. For this purpose I will take the very useful Prolegomena to Ethics of T. H. Green. (Green was a celebrated Oxford moral philosopher, issuing from the revolutionary philosophy of Hegel, rather earlier than Bradley and Bosanquet.) I had better say at once that it is a book that appears to me almost typically unintelligent. It is indeed representative of that blight that morals have insinuated under the skin of most Europeans. The sheer sentimentalism of this revolutionary Protestant moralist is nevertheless a very interesting medium through which to look at the objects of our present concern. One reason for this is that it was the characteristic atmosphere of Anglo-Saxon life, during many years, during which the events of today were being prepared, throughout the world.

4. The Cause of “God and the People”

In speaking of the conscientious perplexities of the religious mind, when it finds the teaching of its dogma in conflict with the interest of the state, Green writes:

The same difficulty . . . in earlier days must have occurred to Quakers and Anabaptists, where the law derived from Scripture seemed contradictory to that of the state, and to those early Christians for whom the law which they disobeyed in refusing to sacrifice retained any authority. In still earlier times it may have arisen in the form of that conflict between the laws of the family and the law of the state, presented in the Antigone. Nor is the case really different when the modern citizen, in his capacity as an official or as a soldier, is called upon to help in putting down some revolutionary movement which yet presents itself to his inmost conviction as the cause of “God and the People.”11

Green goes on to consider what must be the attitude of the philosopher in this painful situation—in which God, or conscience, is upon one side, apparently, and the state, or the organized authority at any given moment, upon the other. He concludes that the philosopher, by the effect of his teaching beforehand upon the minds of the effective minority, may have some useful influence in the moment of crisis:

In preparation for the times when conscience is thus liable to be divided against itself, much practical service may be rendered by a philosophy which, without depreciating the authority of conscience as such, can explain the origin of its conflicting deliverances, and, without pronouncing unconditionally for either, can direct the soul to the true end.12

The counsel of such a philosopher as he has been considering might “have its effect upon the few who lead the many, in preparing the mind through years of meditation for the days when prompt practical decision is required”: that is the point.

In any “conflict between private opinion and authority,” Green’s counsel would always be on the side of the individual and his independent conscience. And indeed to the full-blooded claims of such a conscience to make a wasteland of our life, Green would set positively no bounds at all. Every year conscience must weigh more heavily upon us, as Christian men, he affirms. Every fresh star that swims into our ken is a fresh burden—never a new delight, always an added nightmare. Reflection upon the load we have to carry in comparison with the lighthearted Hellene of Antiquity, provides Green with a long series of dismal reflections, inviting us to an ideal of mechanical and colorless asceticism.

5. Passing “The Point Beyond Which There SeemsNo Longer to Be Either Good or Evil”

To pass the barrier described above by Aristotle into a non-ethical region is not part of the asceticism of this particular kind of moralist, for his “willingness to endure even unto complete self-renunciation, even to the point of forsaking all possibility of pleasure” is envisaged by Green in the most cheerless manner, in a kind of paroxysm of middle-class nineteenth-century Christian duty, that is calculated to make the flesh creep far more thoroughly than could any self-imposed rigors of the gymnosophist:

To an ancient Greek a society composed of a small group of freemen, having recognized claims upon each other and using a much larger body of men with no such recognized claims as instruments in their service, seemed the only possible society. In such an order of things those calls could not be heard which evoke the sacrifices constantly witnessed in the nobler lives of Christendom, sacrifices which would be quite other than they are, if they did not involve the renunciation of those “pleasures of the soul” and “unmixed pleasures,” as they were reckoned in the Platonic psychology, which it did not occur to the philosophers that there could be any occasion in the exercise of the highest virtue to forgo. The calls for such sacrifices arise from that enfranchisement of all men which, though in itself but negative in its nature, carries with it for the responsive conscience a claim on the part of all men to such positive help from all men as is needed to make their freedom real. Where the Greek saw a supply of possibly serviceable labor, . . . the Christian citizen sees a multitude of persons, who in their actual present condition may have no advantage over the slaves of an ancient state, but who in undeveloped possibility, and in the claims which arise out of that possibility, are all that he himself is. Seeing this, he finds a necessity laid upon him. It is no time to enjoy the pleasures of eye and ear, of search for knowledge, of friendly intercourse, of applauded speech or writing, while the mass of men . . . whom we declare to be meant with us for eternal destinies, are left without the chance . . . of making themselves in act what in possibility we believe them to be. Interest in the problem of social deliverance . . . forbids a surrender to enjoyments which are not incidental to that work of deliverance, whatever the value which they, or the activities to which they belong, might otherwise have.

As to this progressive renunciation of every vestige of pleasure, on behalf of this “principle of an abstract value in the human person as such,” Green says:

With every advance towards its universal application comes a complication of the necessity, under which the conscientious man feels himself placed, of sacrificing personal pleasure in satisfaction of the claims of human brotherhood. On the one side the freedom of everyone to shift for himself . . . on the other, the responsibility of everyone for everyone, acknowledged by the awakened conscience: these together form a moral situation in which the good citizen has no leisure to think of developing in due proportion his own faculties of enjoyment.13

The “good citizen’s” lot, having to forgo more and more enjoyment, even “the pleasures of the soul” (which it did not so much as occur to a Greek to sacrifice), is indeed a melancholy one, it seems, as the number of people in the world increases and as the newspapers or cinemas inform him, or put visibly before him, more and more creatures for whom he is “responsible.” This is surely the very madness of morality, for there is no compensating beauty such as you get in the great Catholic mystics; there is nothing but this cold and ever growing, dutiful, quantitative, responsibility.

6. “Every Man Both by Law and Common SentimentIs Recognized as Having a ‘Suum’”

According to Green’s expanding principle of “the common good” there is no limit to such expansion, or to the corresponding depression and ascetic continence of the conscientious Christian. As men we call a halt, however, before animals and things. This at least, for Green, confines the question to the surface of this globe and to two-legged animals: no inhabitant of another world, or a mere horse or cat in this one, can make us unhappy. But to every man we should not only postpone our own interest, but in his behalf, though we may never have seen him but only heard of him, we should abstain from any pleasure, even of the mind. (The abstaining from the “pleasures of the mind” may be a compliment to our neighbor in his capacity of man, in contradistinction to animal.)

In quoting the definition of justice from the Institutes (“Justicia est constans et perpetua voluntas suwn cuique tribuendi”)14, he writes, “Every man both by law and common sentiment is recognized as having a ‘suum’—that is the typical abstract expression of the notion that there is something due from every man to every man.”15 (The mere principle, of course, that everyone, of whatever caste, creed, or race, has a suum, is not sufficient to base our moral conduct upon, as we must first know what suum is.)

But in Green’s view, “there is no necessary limit of numbers or space beyond which the spiritual principle of social relations becomes ineffective.”16 His expansiveness is really infinite, that is to say.

In the whole view of life which [philanthropic work] implies, in the objects which inspire it, . . . a view of life [is implied] in which the maintenance of any form of political society scarcely holds a place: in which lives that would be contemptible and valueless, if estimated with reference to the purposes of the State, are invested with a value of their own in virtue of capabilities of some society not seen as yet.17

This readiness of the fanatical moralist to ignore the claims of “any form of political society” and to give up his life for the publicans and sinners, who are peculiarly adapted to “some society not seen as yet,” gives him an unquestionable advantage over the Greek contemporary with Plato: he proves that the “progress of the species” is not a phantasy. Yet of course, to the superficial eye, the Greek might be supposed to have the best of it. This is an absolute mistake.

Now, when we compare the life of service to mankind, involving so much sacrifice of pure pleasure, which is lived by men whom in our consciences we think best, and which they reproach themselves for not making one of more complete self-denial, with the life of free activity in bodily and intellectual exercises, in friendly converse, in civil debate, in the enjoyment of beautiful sights and sounds, which we commonly ascribe to the Greeks . . . we might be apt, in the first view, to think that, even though measured not merely by the quantity of pleasure incidental to it but by the fulness of the realization of human capabilities implied in it, the latter kind of life was the higher of the two. Man for man, the Greek . . . might seem to be intrinsically a nobler being—one of more fully developed powers—than the self-mortifying Christian, upon whom the sense of duty to a suffering world weighs too heavily to allow of his giving free-play to enjoyable activities.18

“On the first view” you would fall perhaps into that mistake, and as far as this philosopher’s account of the situation is concerned no one could find it in his heart, or conscience, to blame you, I believe. I find it impossible to rescue myself from that initial error.

7. Our World Has Become an Almost Purely EthicalPlace

The “moral situation” which in these quotations from Green I have, I hope, brought clearly before you, is the moral situation that underlies all the questions that are agitating us today. The fundamentals of this situation are clearly explained to you by these quotations from Green. It is a “moral situation,” that is the essential point: our world has become an almost purely ethical place. But since the time of Green much progress has been made—he would scarcely recognize it. (If he came to life again I shudder to think of the sheer avoirdupois of miserable duty that would be added to his already staggering load.) There is the same “moral situation,” but men’s capacity to harm and interfere with each other has immensely increased, and they have not been slow to take advantage of this. So side by side we have an ever-increasing ethical pressure—more and more strenuous streams of moral persuasiveness—and a darker and darker cloud of poison gas always gathering upon the horizon, and larger and larger birds of prey—in the form of airplanes pregnant with colossal bombs—hovering over us; also war-films and war-books multiply at a dumbfounding rate. So it is an intensely “moral situation”: soon any “ascetic” worth his salt will sink immediately beneath the burden, as he steps out of his cradle and looks round—already several are mere specters in our midst, from whose lips issue a few sepulchral words at rare intervals.

Discussing a remark of Matthew Arnold’s regarding righteousness, Samuel Butler made some comments worth considering in this connection. Among other things he wrote as follows:

I would join issue with Mr. Matthew Arnold on yet another point. I understand him to imply that righteousness should be a man’s highest aim in life. I do not like setting up righteousness, nor yet anything else, as the highest aim in life: a man should have any number of little aims about which he should be conscious and for which he should have names, but he should have neither name for, nor consciousness concerning, the main aim of his life. Whatever we do we must try and do rightly—this is obvious—but righteousness implies something much more than this: it conveys to our minds not only the desire to get whatever we have taken in hand as nearly right as possible, but also the general reference of our lives to the supposed will of an unseen but supreme power. Granted that there is such a power, and granted that we should obey its will, we are the more likely to do this the less we concern ourselves about the matter and the more we confine our attention to the things immediately round about us.19

That has a most agreeable sound after Green: the “desire to dogmatise about matters whereon the Greek and Roman held certainty to be at once unimportant and unattainable” (again Butler’s words) grows upon a person or upon a community;20 and though I should not be able to agree with all of Butler’s text, the passion for tolerance, at least, which was such a feature of that light-hearted and penetrating philosopher, is surely today a thing of which we cannot have enough, as we find ourselves hemmed in more and more by righteousness and intolerance.