1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

Maurice Maeterlinck's "P√©ll√©as and M√©lisande; Alladine and Palomides; Home" exemplifies the Symbolist movement, intertwining themes of love, loss, and the ineffable nature of human experience. Through his lyrical prose, Maeterlinck crafts haunting narratives that delve into the psychological and existential dilemmas faced by his characters, set against an otherworldly backdrop. The collection showcases his trademark use of rich imagery and ambient dialogue, effectively conveying profound emotional truths while adhering to a dreamlike quality that invites multiple interpretations'—characteristics that define the literary landscape of early 20th-century European literature. Maurice Maeterlinck was a pioneering Belgian playwright and poet whose work explored the depths of the human psyche. Winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1911, Maeterlinck's contemplation of themes such as fate, the subconscious, and the mysteries of life and death were significantly influenced by his personal experiences and philosophical inquiries. His exploration of tragic love in "P√©ll√©as and M√©lisande" particularly draws from the complexities of relationships, revealing his intimate understanding of emotional intricacies and existential quandaries. This collection is a must-read for anyone interested in Symbolist literature or the interplay of emotion and metaphysical inquiry. Maeterlinck's ability to blend the ethereal with raw human experience provides readers with a profound meditation on love's fleeting nature. Whether for scholarly study or personal reflection, this volume offers a captivating glimpse into the soul's traverses, making it an essential addition to any literary canon. In this enriched edition, we have carefully created added value for your reading experience: - A comprehensive Introduction outlines these selected works' unifying features, themes, or stylistic evolutions. - The Author Biography highlights personal milestones and literary influences that shape the entire body of writing. - A Historical Context section situates the works in their broader era—social currents, cultural trends, and key events that underpin their creation. - A concise Synopsis (Selection) offers an accessible overview of the included texts, helping readers navigate plotlines and main ideas without revealing critical twists. - A unified Analysis examines recurring motifs and stylistic hallmarks across the collection, tying the stories together while spotlighting the different work's strengths. - Reflection questions inspire deeper contemplation of the author's overarching message, inviting readers to draw connections among different texts and relate them to modern contexts. - Lastly, our hand‐picked Memorable Quotes distill pivotal lines and turning points, serving as touchstones for the collection's central themes.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Pélléas and Mélisande; Alladine and Palomides; Home

Table of Contents

Introduction

This collection gathers three landmark dramas by Maurice Maeterlinck—Pélléas and Mélisande; Alladine and Palomides; Home—offering a concentrated entry into the author’s symbolist theatre. Its scope is deliberately focused rather than encyclopedic: these are not complete works, but a carefully aligned triad that traces his vision across courtly, chivalric, and domestic spaces. The sequence moves from the gates, halls, fountains, vaults, and terraces of a castle, to the moats and corridors of a palace, and finally to the intimacies of an ordinary dwelling. The purpose is to present a sustained meditation on human vulnerability before the unknown, as staged through acts and scenes of remarkable restraint.

The texts included here are stage plays. They are dramatic works conceived for performance, composed in lucid, understated prose with an unmistakably lyrical cadence. There are no novels, short stories, essays, or letters in this volume, nor are these dramatic poems in the conventional sense. Instead, Maeterlinck’s method relies on dialogue pared to essentials, suggestive stage directions, and a design in acts and scenes that privileges atmosphere and rhythm over incident. Pélléas and Mélisande unfolds in five acts; Alladine and Palomides likewise proceeds in acts that traverse windows, drawbridges, and apartments; Home is a shorter, concentrated drama whose force lies in the charged stillness of domestic space.

Maurice Maeterlinck, a Belgian author writing in French, is closely associated with Symbolism, the movement that sought to evoke rather than describe, to suggest rather than explain. His theatre helped define a new dramaturgy that privileges silence, shadow, and the weight of unspoken knowledge. His achievement was recognized internationally; he received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1911. The plays in this collection belong to the late nineteenth century and reflect his formative period, when he forged a stage language capable of expressing inward states without resorting to overt psychology. They remain touchstones of modern drama for their audacity, economy, and enduring mystery.

What unifies these works is a sustained attention to the unseen forces—fate, chance, fear, innocence—that shape human bonds while eluding explanation. The dramas repeatedly return to thresholds and borders: gates and corridors, windows and terraces, drawbridges and vaults, fountains and grottoes. Nature’s elements—water above all—become emblems of depth and opacity. Characters often stand near springs, moats, ventilators, and towers, listening rather than acting, sensing rather than declaring. Jealousy, compassion, and duty circulate in these spaces, but motives remain part-veiled, and meaning is carried as much by pauses and movements as by words. The result is a theatre of atmosphere, tact, and ethical attention.

Pélléas and Mélisande unfolds within and around a castle where generations overlap and secret currents run beneath daily life. A woman is found at the brink of a spring; a gate opens on foreboding forests; halls, terraces, and watchman’s rounds mark the passage of time. Older figures such as Arkël and Geneviève preside, while Golaud, Pélléas, Mélisande, and the child Yniold navigate a web of affection, silence, and surveillance. Fountains and vaults, towers and corridors, shape a mood of listening and restraint. The play’s power resides in how it lets tenderness and fear surface in murmurs and gestures rather than in declarations or explanations.

Alladine and Palomides shifts the setting to a palace governed by King Ablamore, where windows open onto a park and a drawbridge spans the moats. Alladine, at first glimpsed at a window and later with her pet lamb upon the bridge, meets Palomides under the watch of courtly authority. Astolaine and the sisters of Palomides introduce countercurrents of expectation and duty. The drama charts the fragile emergence of feeling in a world of vows and prohibitions, where compassion vies with possessiveness and ritual. Corridors, apartments, and the tower’s vantage point create a geometry of sight and concealment that heightens the play’s ethical ambiguity.

Home turns from castles and palaces to the charged intimacy of a household. It focuses on the moment when knowledge borne by those outside must be brought to those within, and the threshold of a home becomes a moral frontier. The drama’s power lies in the tension between the calm, unsuspecting interior and the gravity known to those who approach. Little overt action occurs; instead, attention is directed to faces at windows, the hush of rooms, and the burden of compassion. By bringing the symbolist sensibility into an everyday setting, the play reveals the universal reach of Maeterlinck’s concerns.

Maeterlinck’s style is distinguished by understatement, repetition, and silence. Dialogue is pared to essentials; pauses, ellipses, and slight shifts in tone carry emotional weight. Characters are not vehicles for analytic confession but figures whose inner lives emerge through position and relation: at a gate, beside a fountain, across a drawbridge, before a door. Names suggest an archaic or chivalric world, yet the psychological landscape is modern in its uncertainty. Light and darkness, inside and outside, upstairs and downstairs—these oppositions generate a quiet dramaturgy of thresholds. The resulting plays are less narratives to be decoded than atmospheres to be inhabited.

The stagecraft of these dramas is as expressive as the language. Gates, watchmen’s rounds, ventilators, and tower windows organize space and time; grottos and vaults suggest depth and danger; fountains and springs recall an unknowable source. Children’s voices, distant calls, and footsteps infuse the scenes with an acoustic life, while the architecture imposes paths of approach, delay, and retreat. Such design invites directors to treat sound, light, and stillness as principal actors, and it invites readers to feel space as meaning. The plays are built to be heard as much as read, their rhythms shaped by entrances, hesitations, and the murmur of water.

These works remain significant because they opened a path for modern theatre to treat mystery with dignity rather than explanation. Maeterlinck’s restraint—his refusal to resolve ambiguity or to furnish motives—grants audiences the freedom to attend to ethical nuance and emotional resonance. The plays helped consolidate the Symbolist stage as an alternative to overt naturalism, influencing later experiment in scenography, acting, and music. Their survival in repertory is owed not to spectacle but to generosity: they make space for the spectator’s imagination. The triad here presented shows how that generosity adapts across royal, chivalric, and domestic frames without losing intensity.

Readers new to these plays might approach them as scores for attention. Read slowly; let recurrent images—water, hair, light, windows, corridors—gather meaning by return rather than definition. Accept that knowledge is often offstage and that silence is not emptiness but form. Watch how authority figures and children perceive the same world differently, and how small acts—a glance across a drawbridge, a hand near a spring, a pause before a door—reshape relations. The dramas yield their force by accumulation, not by revelation. Patience with uncertainty is rewarded by a sense of ethical tact that feels at once fragile and exacting.

Taken together, Pélléas and Mélisande; Alladine and Palomides; Home chart a movement from the outer fortifications of public life to the inner rooms of private experience. The settings change—from castle to palace to house—yet the same questions persist: how to love without possession, how to speak without wounding, how to face what cannot be mastered. This edition gathers these plays to present a unified portrait of Maeterlinck’s early theatre, not as a complete body of work but as a coherent constellation. It offers an accessible gateway to his art, in which the unsayable is approached with humility, and the smallest gesture bears the greatest weight.

Author Biography

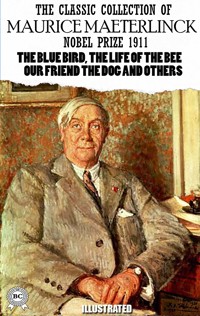

Maurice Maeterlinck (1862–1949) was a Belgian playwright, poet, and essayist who wrote in French and became a central voice of European Symbolism. His drama turned away from naturalist spectacle toward a theater of suggestion, where silence, atmosphere, and the unseen govern human fate. Through works such as Pelléas et Mélisande and The Blue Bird, he helped reshape modern stagecraft and inspired musicians and directors across Europe and beyond. Celebrated for both visionary plays and reflective prose on nature and ethics, he received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1911. His writing continues to be read for its lyrical austerity and metaphysical reach.

Raised in Ghent, Maeterlinck studied law at the University of Ghent and briefly practiced before gravitating to literature. In the late 1880s he spent formative time in Paris, encountering Symbolist circles around Stéphane Mallarmé and the fiction of Villiers de l’Isle-Adam. He published the poetry collection Serres chaudes and the drama La Princesse Maleine in 1889. The latter drew fervent praise from Octave Mirbeau in the Paris press, placing Maeterlinck at the forefront of a new movement. He pursued a language of suggestion that favored mystery, metaphysical unease, and inward action, setting the terms for a distinctive theatrical idiom.

Early plays such as L’Intruse and Les Aveugles (early 1890s), followed by Pelléas et Mélisande (1892), established Maeterlinck as a dramatist of the invisible. Often staged at Paris’s Théâtre de l’Œuvre under Lugné-Poe, these works exemplified his théâtre statique, in which events transpire largely offstage while characters wait, fear, or listen. The effect is hypnotic rather than plot-driven, emphasizing fate and the limits of human knowledge. Pelléas et Mélisande later gained wide renown through Claude Debussy’s opera, while composers including Gabriel Fauré and Jean Sibelius wrote celebrated incidental music for the play, expanding its reach across different arts.

Through the later 1890s and early 1900s, Maeterlinck diversified his stage forms while preserving a symbolist core. Intérieur and Aglavaine et Sélysette refined his austere dramaturgy, and Ariane et Barbe-bleue (1901) and Monna Vanna (1902) broadened his audience with more expansive dramatic canvases. His fairy play The Blue Bird (1908), an allegory of the search for happiness, became an international success and a durable favorite in repertory. Across these works he balanced fatality with wonder, developing a theater that could be intimate yet public, philosophical yet accessible. His reputation grew as productions multiplied in European capitals and beyond.

Parallel to his theater, Maeterlinck pursued an influential line of prose meditations on nature and ethics. The Life of the Bee (1901) and The Intelligence of Flowers (1907) combine observation with metaphor to ask what human communities might learn from nonhuman ones. He later extended this inquiry to social insects in La Vie des Termites (1926) and La Vie des Fourmis (1930). These books reached broad audiences, though some scientists questioned their accuracy, and La Vie des Termites drew accusations of plagiarism from the South African writer Eugène Marais. Despite debate, the prose remains admired for its clarity, curiosity, and moral imagination.

Maeterlinck’s stature as a public intellectual peaked in the early 1910s, when he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature (1911) for his profoundly imaginative drama. During the First World War he published essays and lectures, gathered in English as The Wrack of the Storm (1916), that reflected on Belgium’s ordeal and on civic courage. He continued to write plays and essays in subsequent decades and resided largely in France while maintaining his Belgian identity. His multifaceted career—poetry, theater, and natural philosophy—made him one of the few symbolist writers to command both avant-garde admiration and a broad general readership.

In his later years Maeterlinck remained a widely recognized figure, even as tastes shifted and younger movements challenged Symbolism. He died in 1949 in Nice, leaving a body of work that continues to influence playwrights, composers, and essayists. Today Pelléas et Mélisande is often studied alongside Debussy’s opera, while The Blue Bird endures in adaptations for stage and screen. Directors draw on his use of silence, offstage space, and the poetics of waiting; readers return to his nature books for their lucid metaphors and ethical questions. His legacy centers on a rare union of theatrical innovation and contemplative prose.

Historical Context

Maurice Maeterlinck (1862–1949), born in Ghent, Belgium, emerged in the 1890s as a major voice of Symbolist drama. Educated in law at the University of Ghent and admitted to the bar in 1886, he soon abandoned legal practice for literature, writing in French and moving between Ghent, Brussels, and Paris. Pelléas et Mélisande (written 1892; premiered Paris, 1893), Alladine et Palomides (1894), and Intérieur—often translated as Home (1895)—belong to his first, profoundly influential theatrical phase. These works established his austere poetics of silence, fatality, and atmosphere, setting the stage for later recognition, including the 1911 Nobel Prize in Literature, which crowned a career spanning drama, essays, and prose.

The late nineteenth-century Symbolist movement, centered around figures like Stéphane Mallarmé and Paul Verlaine in Paris and mirrored in francophone Belgium, forms the essential backdrop to Maeterlinck’s theatre. Symbolism arose in reaction to Naturalism’s photographic fidelity, favoring suggestion over description and music over logic. Belgian periodicals such as La Wallonie (founded by Albert Mockel in 1886) and La Jeune Belgique cultivated the new idiom; Octave Mirbeau’s 1890 panegyric to La Princesse Maleine in Le Figaro announced Maeterlinck’s arrival. Against the bustling industrial and colonial Belgium of the 1880s–90s, Symbolists sought interiority, mystery, and ritualized speech—traits that shape Pelléas, Alladine, and Home alike.

Parisian avant-garde theatres turned Maeterlinck’s scripts into stage practice. Paul Fort’s Théâtre d’Art presented L’Intruse and Les Aveugles in 1891, proving that hushed, static dramaturgy could hold an audience. Aurélien Lugné-Poe founded the Théâtre de l’Œuvre in 1893 and premiered Pelléas et Mélisande the same year, using borrowed venues like the Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens. Stripped décor, softened lighting, and an anti-declamatory acting style replaced Naturalist interiors. These institutions forged a pan-European network that also staged Ibsen and Strindberg, situating Maeterlinck’s castle corridors, towers, and fountains within a broader quest to render the unseen dimensions of human fate on a simplified, resonant stage.

Fin-de-siècle medievalism—visible in Arthurian revivals, Pre-Raphaelite art, and Wagnerian myth—nourished Maeterlinck’s settings and names. Pelléas, Mélisande, Golaud, and the Saracen knight Palomides echo chivalric sources while resisting historical specificity. This strain aligned with contemporaneous enthusiasm for Bayreuth even as certain French modernists, including Debussy, reacted against Wagner’s excess. Maeterlinck’s castles, drawbridges, and grottoes are less historical reconstructions than symbolic architectures for inner conflict. The medieval aura afforded distance from the journalistic present, allowing his characters to move within timeless, half-lit spaces where words are incantatory signs and objects—rings, locks, fountains—become emblems of desire, secrecy, and a destiny felt more than explained.

Philosophical currents shaped the somber metaphysics of these dramas. Maeterlinck read Arthur Schopenhauer and Eduard von Hartmann and engaged with mystical traditions including the Flemish visionary Jan van Ruusbroec (Ruusbroeck). His essays in Le Trésor des humbles (1896) meditate on silence, intuition, and the “unknown” that encircles daily life. He proposed that the tragic stems not from spectacular events but from the slow pressure of the inevitable. These ideas infuse Pelléas, Alladine, and Home: the stillness of thresholds, the watchman’s distant call, and the muffled voice behind a door dramatize metaphysical suspense, suggesting that destiny gathers in pauses, shadows, and the unspoken more than in action.

Belgium’s bilingual, rapidly industrializing society, newly independent since 1830 and increasingly prominent in European finance and trade, provided Maeterlinck an ambivalent vantage. From Ghent’s textile milieu he entered francophone literary circuits that linked Brussels and Paris. Print culture was dense: journals, salons, and small presses fostered experimental writing. While the Congo Free State (established 1885) shadowed Belgium’s global presence, francophone letters in the 1890s often turned inward, privileging spiritual exploration over topical realism. Within this environment Maeterlinck’s curt, tonally hushed dialogues, and his preference for anonymous realms rather than named cities, signaled both detachment from and reaction to the noise of modern urban life.

Maeterlinck’s dramaturgy has been called “static” not for being inert but for converting action into atmosphere. His programmatic essay “Le Tragique quotidien” (1896) argued that waiting, listening, and fearing are the true modern catastrophes. Hence the recurring stage grammar: doors that never fully open, corridors without exits, and ritualized arrivals and departures. Such forms unify Pelléas, Alladine, and Home, where the event is often deferred until the audience has inhabited a mood. Speech operates as tremor rather than declaration; silence bears weight; the watchman’s rounds or a fountain’s murmur calibrate time. The plays’ structures thus reflect an ethics of attention, patience, and intangible causality.

Music amplified Maeterlinck’s reputation across Europe. Claude Debussy’s opera Pelléas et Mélisande premiered at the Opéra-Comique on 30 April 1902, with Jean Périer as Pelléas and Mary Garden as Mélisande, reimagining the play’s half-lights in orchestral color. Gabriel Fauré composed incidental music for an English production in London in 1898; he derived a concert suite later known as Op. 80. Arnold Schoenberg completed his symphonic poem Pelleas und Melisande in 1903, and Jean Sibelius wrote incidental music for a Helsinki staging in 1905. These adaptations attest to the scripts’ musicality and to Symbolism’s aspiration to the condition of music—suggestive, fluid, and indeterminate.

Anglophone reception accelerated via translation and little-press culture. In Chicago, Stone & Kimball published Richard Hovey’s English versions as Pelléas and Mélisande; Alladine and Palomides; Home (mid-1890s), circulating Maeterlinck among American aesthetes associated with The Chap-Book. In London, Laurence Alma-Tadema’s translation underpinned the 1898 Prince of Wales Theatre production that prompted Fauré’s score. The title “Home” reflects a period convention for Intérieur, emphasizing domestic tragedy perceived from the threshold. These translations aligned Maeterlinck with Oscar Wilde, W. B. Yeats, and the broader “literary theatre” movement that prized poetic text and atmosphere over conventional realism, influencing staging practices on both sides of the Atlantic.

New stagecraft enabled the plays’ distinctive optics. At the Théâtre de l’Œuvre, designers affiliated with the Nabis—Édouard Vuillard and Maurice Denis—experimented with flat planes, draperies, and silhouettes to soften perspective. Innovations in lighting, from gas to early electrical systems, made possible the low intensities and lateral glows Symbolists favored. Theorists Adolphe Appia and later Edward Gordon Craig argued for abstract scenery, mobile light, and the actor as hieratic figure, ideas convergent with Maeterlinck’s needs. Curtains, scrims, and gauzes suggested gardens, towers, and vaults without literal reproduction, letting verbal music and gesture carry meaning while objects—a ring, a window—took on talismanic force.

The fin de siècle was marked by nervous modernity: medical discourses of hysteria and neurasthenia (popularized by Jean-Martin Charcot’s demonstrations at the Salpêtrière), urban overstimulation, and a press culture that sensationalized threat. Political crises like the Dreyfus Affair (1894–1906) polarized French society. Symbolists sought antidotes to reportage and clinical detail, recentering intuition and myth. Maeterlinck’s preference for unnamed kingdoms, watchful elders, and tremulous children resonates with this climate, transmuting social anxiety into metaphysical dread. The plays’ vigilance—faces bent to windows, ears pressed to doors—mirrors a broader culture of surveillance and rumor while preserving an ethical ambiguity alien to newspaper certainties.

Maeterlinck’s theatre conversed with contemporaneous European innovators. While André Antoine’s Théâtre Libre advanced Naturalism, Henrik Ibsen and August Strindberg retooled drama toward psychological crisis; Gerhart Hauptmann explored social determinism. Maeterlinck diverged by stripping causality to bare suggestion. His brief for puppet theatre—marionettes untroubled by individual ego—challenged the star system and psychological nuance then ascendant. W. B. Yeats absorbed this anti-naturalist poetics into the Irish Literary Theatre (founded 1899), where stylized speech and mythic settings found a home. In this pan-European milieu, Pelléas, Alladine, and Home exemplify a shared desire to exceed reportage and recover ritual from the ruins of modern spectacle.

Gender and performance history intertwined with Maeterlinck’s life. From 1895, the soprano Georgette Leblanc became his companion and a key interpreter, shaping productions and public image. Their partnership collided with Debussy’s opera when the Opéra-Comique engaged Mary Garden, not Leblanc, for the 1902 premiere; Maeterlinck protested publicly, even attempting to revoke rights. The episode, widely reported, exposed tensions between authorial control and musical theatre institutions. More broadly, Maeterlinck’s women—Mélisande, Alladine, and the silent figure at the center of Home—embody fin-de-siècle debates over interiority, vulnerability, and agency, yet resist the “New Woman” discourse by remaining deliberately enigmatic, framed by watchful patriarchs and archaic law.

Critical response oscillated between reverence and skepticism. Octave Mirbeau’s early advocacy contrasted with attacks on obscurity or passivity from detractors shaped by Zola. In Belgium and France, Catholic and republican critics alike debated the moral valence of Symbolist theatre. Despite intermittent controversies, Maeterlinck’s reputation grew steadily through the 1890s, consolidated by essay collections—Le Trésor des humbles (1896), La Sagesse et la destinée (1898)—that articulated the ethical horizon behind the plays. The 1911 Nobel Prize recognized the breadth of his oeuvre, but the award also canonized the early dramas as a decisive reorientation of theatrical language toward suggestion, inner life, and metaphysical quiet.

Geography in these works functions as atmosphere rather than map. The damp forests, seashores, and somber halls evoke a northern imaginary akin to Belgian compatriot Georges Rodenbach’s Bruges-la-Morte (1892), where water, bells, and fog index memory and loss. In Maeterlinck, fountains and grottoes signal thresholds between surface and depth; towers and vaults spatialize hierarchy and concealment. Such settings traverse Pelléas, Alladine, and Home, binding an aristocratic past to a modern sense of estrangement. The landscapes’ indeterminacy enabled international audiences—from Paris to London and Helsinki—to project local longings onto a universal stage of twilight, rumor, and the uncanny persistence of fate.

Though later celebrated for The Blue Bird (1908) and for reflective prose on nature—The Life of the Bee (1901), The Intelligence of Flowers (1907)—Maeterlinck’s 1890s plays remained central to European repertoires. World War I, the 1914 German invasion of Belgium, and his subsequent exile on the Riviera shifted his focus toward essays like The Wrack of the Storm (1916), yet companies kept returning to the early works for their portable staging and musical pliability. Their economy of means suited small theatres and emerging film and radio aesthetics, ensuring that, even as his themes evolved toward a tempered optimism, the earlier nocturnes continued to resonate.

Historically, this collection belongs to a moment when artists rebuilt theatre from first principles—language as spell, space as symbol, and time as suspense. The institutional frameworks of Théâtre d’Art and Théâtre de l’Œuvre, the cross-media embrace by composers from Fauré to Sibelius, and transatlantic translators like Richard Hovey and Laurence Alma-Tadema formed a circuit that carried these scripts far beyond Brussels and Paris. Reading Pelléas et Mélisande, Alladine et Palomides, and Home today, one encounters not discrete curiosities but a shared fin-de-siècle experiment: to distill modern anxiety and ethical yearning into ritualized scenes, where a door, a window, and a voice in the night suffice.

Synopsis (Selection)

Pelléas and Mélisande

In a somber, symbolist court, the enigmatic Mélisande—found and married by Prince Golaud—forms a deep, forbidden bond with his half-brother Pelléas as secrecy, jealousy, and the oppressive castle atmosphere close in. Their hesitant encounters and Golaud’s mounting suspicion lead toward an inevitable, tragic confrontation.

Alladine and Palomides

A dreamlike romance in which the young knight Palomides and the innocent Alladine fall in love under the possessive gaze of King Ablamore, who subjects them to ordeals within a labyrinthine palace. Misunderstandings, tests of fidelity, and perilous spaces shape their fate with fairytale ambiguity.

Home

A one-act drama set outside a family’s house, where two men struggle with how to announce a devastating loss to the unsuspecting household within. The tension builds through the contrast between the tranquil interior and the burden of the messengers at the door.