1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

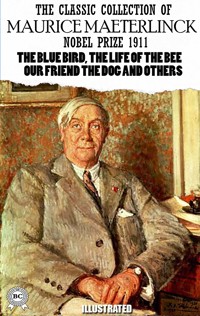

'ÄúPell√©as and M√©lisande'Äù is a profound exploration of symbolist and impressionist artistry that intertwines the dramatic with the musical in a timeless narrative form. The anthology pivots on the renowned play by Maurice Maeterlinck, expertly interwoven with the atmospheric compositions of Claude Debussy. It encompasses a range of literary and artistic expressions, venturing deep into themes of love, fate, and existential mystery through its rich symbolism and ethereal musical landscapes. This curated collection offers a wholly unique intersection between drama and music, presenting standout sections that capture the somber beauty and haunting resonance of the central narrative without isolating any single piece. Both Maeterlinck and Debussy were pivotal figures in their respective movements, contributing to the birth of new artistic sensibilities at the turn of the century. Maeterlinck's poignant, almost mystical storytelling complements Debussy's revolutionary musical impressionism, both echoing the prevailing currents of symbolist thought and reflecting their shared aims of evoking mood and emotion over direct narrative clarity. As such, this anthology situates itself firmly in the historical context of late 19th-century artistic exploration, offering readers insights into the cultural fabric that inspired these towering creative minds. This collection is an indispensable resource for those looking to immerse themselves in the layered complexities of early modernist thought. By bringing together the innovative voices of Maeterlinck and Debussy, the anthology not only enriches our understanding of their contributions but also invites readers to experience the synergy of words and music. 'ÄúPell√©as and M√©lisande'Äù promises an enlightening journey through a tapestry of intertwined themes and perspectives, making it an essential read for anyone eager to grasp the evolution of symbolist literature and impressionist music. In this enriched edition, we have carefully created added value for your reading experience: - A succinct Introduction situates the work's timeless appeal and themes. - The Synopsis outlines the central plot, highlighting key developments without spoiling critical twists. - A detailed Historical Context immerses you in the era's events and influences that shaped the writing. - An Author Biography reveals milestones in the author's life, illuminating the personal insights behind the text. - A thorough Analysis dissects symbols, motifs, and character arcs to unearth underlying meanings. - Reflection questions prompt you to engage personally with the work's messages, connecting them to modern life. - Hand‐picked Memorable Quotes shine a spotlight on moments of literary brilliance. - Interactive footnotes clarify unusual references, historical allusions, and archaic phrases for an effortless, more informed read.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Pelléas and Melisande

Table of Contents

Introduction

In a twilight forest, a lost young woman and a searching man cross paths, and from their hesitant words springs a love that stirs shadows no will can command.

Pelle9as and Melisande endures as a classic because it crystallizes the Symbolist ambition to reveal mystery through suggestion, while also reshaping the sound and movement of modern opera. Maurice Maeterlincks play transformed late nineteenth-century theater by privileging atmosphere over action, silence over explanation, and the unseen over the obvious. Claude Debussys operatic setting extended that revolution into music, establishing a new kind of lyric drama that favors speech-like inflection and orchestral color over display. Together, text and score opened doors for twentieth-century artists who sought intensity without rhetoric, intimacy without sentimentality, and emotion conveyed through the smallest tremors of language and tone.

Key facts anchor this work in a specific cultural moment. Maeterlinck, a Belgian Symbolist, wrote Pelle9as et Me9lisande in the 1890s, crafting a drama of veiled motives and fatal tenderness. Debussy, a French composer at the forefront of musical modernism, fashioned his opera from the same text, and it premiered in 1902 at the Ope9ra-Comique in Paris. The story unfolds in a shadowed, indeterminate kingdom where past and present seem to overlap, and where nature listens as closely as any person. Through a restrained vocabulary and deliberate pacing, both artists pursued a poetic art that invites contemplation rather than spectacle.

At its simplest, the premise is hauntingly clear. A prince, lost while hunting, encounters a frightened young woman by a pool deep in the woods. He brings her to a hushed, ancient castle, where the light feels older than the stones. There, his half-brothers presence draws the womans attention with an innocence that unsettles everyone. Small gestures carry the weight of vows; whispered confidences echo louder than declarations. The drama moves through meetings at wells, towers, and gardens, where the natural world seems to record each tremor of feeling. What happens is less important than how it is felt and perceived.

Maeterlincks intention was not to explain human behavior but to surround it with a halo of mystery, rendering the familiar uncanny and the intimate elusive. He created characters who speak in plain words and yet remain opaque, as if their truest selves are visible only in silence and shadow. Debussys purpose was allied but distinct: to translate this atmosphere into music that breathes and listens, replacing conventional operatic rhetoric with speech-inflected lines, translucent harmonies, and an orchestra that murmurs the subconscious. Their combined artistry draws attention to thresholdsthe edge of speech, the brink of choicewhere meaning arises from suggestion rather than assertion.

The plays classic status in literary history owes much to its decisive break with naturalism. Here, plot recedes and the senses rule; events are less causes and effects than correspondences and echoes. Stage time dilates, as if the heart kept its own clock. Maeterlincks pared diction, repetitions, and pregnant pauses influenced later explorations of minimal action and interiority, offering a counter-tradition to theatrics of bustle and argument. This quiet radiance also encouraged directors and readers to imagine a theater of atmosphere, where lighting, silence, and gesture are as eloquent as speech. That legacy persists, making the text a touchstone for poetic drama.

In music, Debussys setting became a watershed. Rejecting grand arias and emphatic cadences, he wrote vocal lines that seem to hover between song and speech, while the orchestra paints water, stone, wind, and the tremor of thought. The result challenged prevailing Wagnerian models with a distinctly French sensibility of light, color, and restraint. Its influence spread widely: composers responded to Maeterlincks story in other idioms, and the operas sound world helped chart new paths for twentieth-century stage music. The work demonstrated that opera could be intimate without losing dramatic potency, that nuance could sustain tension, and that ambiguity could be musically eloquent.

Certain motifs guide the reader like constellations. Water glimmers at crucial moments, suggesting depth, chance, and the pull of things unseen. Hair, light, and rings become emblems of trust, vulnerability, and the fragile bonds people weave in darkness. Forest, cavern, and seaside create a landscape where the outer world mirrors inner weather. Doors half open, windows frame uncertain horizons, and the castles corridors feel like the pathways of memory itself. These elements are not explained so much as allowed to resonate, inviting readers to sense connections that characters cannot name. Such symbolism yields an experience that is both intimate and mythic.

Reading the play or encountering the opera, one meets a language of near-whispers and afterglows. Maeterlincks scenes often end where others would begin, and his pauses invite the imagination to occupy the space between words. Debussy amplifies that invitation: harmonic veils lift and settle, instruments trace inner hesitations, and voices move with the grain of speech. The collaboration across text and music is less illustration than fusion; each justifies and renews the other. This unity helps the story feel inevitable without being foregone, and emotionally transparent without surrendering its mystery, a balance that few works manage and fewer still sustain over time.

The works reach has been unusually broad. The play has been translated into many languages and staged in varied theatrical traditions, each finding new shades in its silences. Debussys opera remains central to the repertory, regularly recorded, performed, and reinterpreted by conductors and directors who prize its inward intensity. Composers have also returned to this tale in other forms, writing incidental music and symphonic poems that attest to its allure. Such ongoing engagement indicates a living classic: not a relic, but a work that continues to generate artistry, scholarship, and debate, revealing fresh facets as sensibilities shift.

For contemporary readers, the allure lies in how the piece treats emotion as a landscape rather than a verdict. It attends to the difficulty of knowing oneself and others, to the way kindness and desire can blur, and to the dangers of speaking when listening might suffice. It also honors the dignity of not knowing, refusing to reduce mystery to diagnosis. In a culture that prizes certainty and speed, Pelle9as and Melisande invites patience, receptivity, and attention to tone. The result is not antiquarian but urgent: an ethics of perception that feels newly necessary amid noise and haste.

Ultimately, this work remains vital because it fuses restraint with intensity, grace with gravity. Its central ideasloves opacity, the burden of jealousy, the nearness of fate, and the eloquence of the natural worldare enduring. Its qualitieslucid language, evocative imagery, and music that seems to breathecontinue to move audiences who seek complexity without clutter. As a landmark of Symbolist drama and a cornerstone of modern opera, Pelle9as and Melisande offers a singular experience: a world where the quietest gestures can alter the air, and where listening becomes a form of seeing. That is why it remains compelling now, and likely will for generations.

Synopsis

Pelléas and Mélisande is a symbolist drama by Maurice Maeterlinck, later fashioned by Claude Debussy into an opera that preserves the play’s spare dialogue and elusive tone. Set in the misted realm of Allemonde, the story follows a subdued love triangle whose tensions emerge through suggestion rather than overt action. Water, forest, and shadow recur as quiet emblems of fate. Debussy’s adaptation maintains the narrative sequence while underscoring its half-lit moods with flexible, speechlike melody and shimmering orchestration. Across both versions, events unfold with measured restraint, inviting attention to pauses, glances, and silences as characters approach choices that neither words nor reason can fully clarify.

Lost during a hunt, the prince Golaud discovers Mélisande weeping beside a spring deep in a forest. She is young, fearful, wearing a crown she refuses to keep, and she will not speak of her past or why she fled. Golaud leads her away and, between scenes, marries her. Their union begins with secrecy and distance, shaped more by circumstance than understanding. Letters home announce the marriage, and the couple travels to Allemonde, a dim coastal domain where the old King Arkel, Golaud’s mother Geneviève, and the younger half brother Pelléas await their arrival, uncertain about the newcomers and the fragile calm they bring.

At the castle, time seems suspended. Arkel is aging and ill, the land feels starved of light, and the sea encroaches with melancholy rhythm. Pelléas lingers between youth and obligation, waiting for signs about whether he may leave or must remain. Mélisande, overwhelmed by the gloom, longs for air and sunlight. She and Pelléas meet in the gardens and by the sea. Their conversations are simple and unsure, yet affinity gathers in pauses and smiles. Golaud, recovering from injuries, notices little at first. The household sustains a polite order, while small incidents begin to create subtle threads binding the younger pair.

By a fountain, Pelléas playfully watches Mélisande as she loosens a ring Golaud gave her. At noon, the ring slips into the water and disappears. Almost at once, word arrives that Golaud has fallen from his horse and is hurt. When he asks for the ring, Mélisande falters and cannot tell the truth. To retrieve it, Golaud orders her to search the shoreline caverns at night, sending Pelléas to guide her. In the echoing grottos, the sea breathes close and strange lights shine on sleeping beggars. Unease grows. Pelléas brings Mélisande back, and the loss remains, a quiet weight beneath the household.

Days later, Mélisande leans from a high window, combing her long hair into the wind. Pelléas arrives below, and in a playful moment her hair falls over him like a shining veil. Their laughter rises toward the sky. Golaud comes upon the scene, startled by the intimacy he glimpses. Afterward, he cautions Pelléas to avoid Mélisande, invoking duty, appearances, and the need for prudence in a house already trembling with uncertainty. He leads Pelléas through the underground vaults, where heavy air and ancestral tombs suggest a warning. The world of Allemonde seems to close in, and suspicions begin to harden.

Golaud, still unsure, turns to his young son Yniold for answers. In a troubling scene, he questions the child and attempts to spy on the pair through Mélisande’s window, seeing little but darkness and hearing vague words. The tension spreads through the castle, felt in shutters that refuse to open and paths that twist back upon themselves. Pelléas, sensing danger and compelled by obligations elsewhere, resolves to depart. Before leaving, he asks to see Mélisande one last time at the fountain near the castle gates. Arkel, expecting change in the family and the realm, looks on with measured patience and concern.

Night falls as Pelléas and Mélisande meet by the fountain for a final conversation. Their guarded exchanges become clear, and words that once hovered at the edge of speech are finally spoken. Around them, trees stir and the sea murmurs, as if the landscape listened. The moment is tender yet solemn, shaped by an awareness of consequence. Golaud, who has followed the growing closeness with mounting agitation, arrives. What happens next shifts the household irrevocably, replacing ambiguity with stark action. The narrative does not linger on details; it lets the shock break the fragile equilibrium and sends each character inward, altered and silent.

In the aftermath, quiet returns with an almost ritual stillness. Mélisande appears withdrawn and fragile, her thoughts moving in small circles, while Golaud vacillates between remorse, anger, and a search for certainty that never yields clarity. Arkel observes with compassionate reserve, speaking of innocence that may suffer without understanding why. Servants and attendants pass quietly, maintaining the rhythms of a house that endures events it cannot interpret. Debussy’s adaptation deepens the hushed atmosphere with translucent harmonies and recurring motifs that trace memory more than plot. The story closes on subdued voices and dim light, emphasizing mystery over explanation.

Across play and opera, Pelléas and Mélisande presents a concentrated study of fate, secrecy, and the opacity of desire. It favors suggestion over declaration, trusting listeners and readers to connect gestures, images, and silences. Key events emerge as ripples on a still surface: a lost ring, a hair loosened to the wind, a child’s uncertain testimony, a meeting after dark. The work’s central message is that human lives often move within currents they scarcely perceive, where love, duty, and fear guide choices more than reason does. Its restrained progression, preserved in Debussy’s setting, leaves a lasting impression of beauty touched by enigma.

Historical Context

Pelléas et Mélisande is set in the indeterminate medieval principality of Allemonde, a shadowed northern realm of forests, cliffs, and a stone citadel overlooking the sea. The time is never dated, yet the social fabric evokes the High to Late Middle Ages, roughly the twelfth to fourteenth centuries, when feudal lordship, dynastic marriage, and castle-centered governance structured daily life. The drama’s wells, crypts, and winding passages point to fortified architecture and the hydraulic needs of hilltop strongholds. The governing house’s succession anxieties, the reliance on oaths and kinship, and the isolation of the court from common people all mirror medieval power’s private, inward character.

The imagined geography—dense woods where fugitives can hide, a castle bridging lightless interiors and perilous overlooks, and a port exposed to storms—corresponds to northern Europe’s maritime-border polities that thrived on trade yet feared incursion. The landscape’s springs and mines suggest resource-based lordship, while the rigid etiquette of the hall and the surveillance implied by towers recall feudal households where lineage honor was policed. Such a setting allows the plot’s secrets, sudden marriages, and lethal jealousies to unfold in a world where law is the lord’s will and where women’s fates are tied to alliances, dowries, and the calculations of male relatives.