35,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

This seminal work—now available in a 15th anniversary edition with a new preface—is a thorough introduction to the historical and theoretical origins of postcolonial theory.

- Provides a clearly written and wide-ranging account of postcolonialism, empire, imperialism, and colonialism, written by one of the leading scholars on the topic

- Details the history of anti-colonial movements and their leaders around the world, from Europe and Latin America to Africa and Asia

- Analyzes the ways in which freedom struggles contributed to postcolonial discourse by producing fundamental ideas about the relationship between non-western and western societies and cultures

- Offers an engaging yet accessible style that will appeal to scholars as well as introductory students

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 1254

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Preface to the Anniversary Edition

Preface to the First Edition

Acknowledgements

1 Colonialism and the Politics of Postcolonial Critique

Part I: Concepts in History

2 Colonialism

1 COLONIALISM AND IMPERIALISM: DEFINING THE TERMS

2 COLONIZATION AND DOMINATION

3 Imperialism

1 THE FRENCH INVENTION OF IMPERIALISM

2 DIFFERENCES IN IMPERIAL IDEOLOGIES AND COLONIAL SYSTEMS

3 BRITISH IMPERIALISM

4 GREATER BRITAIN

5 AMERICAN IMPERIALISM

4 Neocolonialism

1 NEOCOLONIALISM: THE LAST STAGE OF IMPERIALISM

2 DEVELOPMENT AND DEPENDENCY THEORY

3 CRITICAL DEVELOPMENT THEORY

5 Postcolonialism

1 STATES

2 LOCATION

3 KNOWLEDGE

4 LANGUAGE

Part II: European Anti‐colonialism

6 Las Casas to Bentham

1 THE HUMANITARIAN OBJECTION

2 THE ECONOMIC OBJECTION

7 Nineteenth‐Century Liberalism

1 NINETEENTH‐CENTURY ANTI‐COLONIALISM IN FRANCE: ALGERIA AND THE

MISSION CIVILISATRICE

2 NINETEENTH‐CENTURY ANTI‐COLONIALISM IN BRITAIN

3 INDIA

4 IRELAND

5 J. A. HOBSON’S

IMPERIALISM: A STUDY

8 Marx on Colonialism and Imperialism

1 COLONIALISM AND IMPERIALISM IN MARX

2 MARXIST THEORIES OF IMPERIALISM

Part III: The Internationals

9 Socialism and Nationalism

1 THE FIRST AND SECOND INTERNATIONALS

2 ‘BIN GAR KEINE RUSSIN, STAMM’ AUS LITAUEN, ECHT DEUTSCH’: SOCIALISM AND NATIONALISM

3 THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION: MARXISM AND THE NATIONAL QUESTION

10 The Third International, to the Baku Congress of the Peoples of the East

1 THE FORMATION OF THE THIRD INTERNATIONAL

2 THE SECOND CONGRESS, JULY–AUGUST 1920

3 THE BAKU CONGRESS, SEPTEMBER 1920

11 The Women’s International, the Third and the Fourth Internationals

1 THE INTERNATIONALS AND THE COMMUNIST WOMEN’S MOVEMENT

2 THE THIRD CONGRESS OF THE COMINTERN, JUNE–JULY 1921

3 THE FOURTH CONGRESS OF THE COMINTERN, NOVEMBER–DECEMBER 1922

4 THE FIFTH CONGRESS OF THE COMINTERN, JULY 1924

5 THE SIXTH AND SEVENTH CONGRESSES OF THE COMINTERN, 1928 AND 1935

6 TROTSKY AND THE FOURTH INTERNATIONAL

Part IV: Theoretical Practices of the Freedom Struggles

12 The National Liberation Movements

13 Marxism and the National Liberation Movements

1 ABDEL‐MALEK ON MARXISM AND THE LIBERATION MOVEMENTS

2 PERIOD ONE: TO 1928

3 PERIOD TWO: 1928–1945

4 PERIOD 3: AFTER 1945

14 China, Egypt, Bandung

1 MAO AND THE CHINESE REVOLUTION

2 CONTRADICTION IN MAO

3 THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION

4 EGYPT

5 NASSER

6 THE BANDUNG CONFERENCE OF 1955

15 Latin America I

1 MARXISM IN LATIN AMERICA

2 MEXICO 1910

3 MARIÁTEGUI

4 CULTURAL DEPENDENCY

16 Latin America II

1 COMPAÑERO: CHE GUEVARA

2 NEW MAN

3 THE TRICONTINENTAL

17 Africa I

1 PRE‐COMMUNIST AFRICAN ANTI‐COLONIALISM

2 THE INFLUENCE OF AFRICAN‐AMERICAN ANDAFRICAN‐CARIBBEAN RADICALS

3 COMMUNIST ACTIVITY IN AFRICA

4 SOUTH AFRICA

5 PADMORE AND JAMES

18 Africa II

1 THE 1945 MANCHESTER PAN‐AFRICAN CONGRESS

2 AFRICAN SOCIALISM

3 NKRUMAH

4 NYERERE

5 FROM ‘POSITIVE ACTION’ TO VIOLENCE

19 Africa III

1 FRANCE BETWEEN THE WARS

2 ANTI‐COLONIAL ACTIVISTS: HOUÉNOU, SENGHOR AND GARAN KOUYATÉ

3 TOVALOU HOUÉNOU AND THE LIGUE UNIVERSELLE DE DÉFENSE DE LA RACE NOIRE (LDRN)

4 LAMINE SENGHOR AND THE COMITÉ DE DÉFENSE DE LA RACE NÈGRE (CDRN)

5 TIÉMOHO GARAN KOUYATÉ AND THE LIGUE DE DÉFENSE DE LA RACE NÈGRE (LDRN)

6 THE CULTURAL TURN:

NÉGRITUDE

7 LÉOPOLD SENGHOR

20 Africa IV

1 FRANTZ FANON

2 FANON AND FRANCOPHONE AFRICAN POLITICAL THOUGHT

3 FANON AND ALGERIA

4 FANON AND VIOLENCE

5 CABRAL: CULTURE AS RESISTANCE AND LIBERATION

6 THE WEAPON OF THEORY

7 THE ROLE OF CULTURE

21 The Subject of Violence

1 SUBJECT, SUBJECTION

2 VIOLENCE, VIOLATION

3 NERVOUS CONDITIONS

4 IRELAND: ASSIMILATION AND VIOLENCE

5 IRELAND AND POSTCOLONIAL THEORY

6 ‘IRELAND LOST, THE BRITISH “EMPIRE” IS GONE’: JAMES CONNOLLY AND THE EASTER REBELLION OF 1916

22 India I

1 THE UNIQUENESS OF THE INDIAN INDEPENDENCE MOVEMENT

2 INDIAN SOCIALISM: FROM SOCIALISM TO

SARVODAYA

3 MARXISM IN INDIA

23 India II

1 CULTURAL NATIONALISM

2

AHIMSA

: VIOLENCE AND NON‐VIOLENCE

3 GANDHI’S ALTERNATIVE POLITICAL STRATEGIES

4 THE DANDI MARCH

5 GANDHI IN LANCASHIRE

Part V: Formations of Postcolonial Theory

24 India III

1 GANDHI’S INVISIBILITY

2 INTIMATE ENEMY

3 DERIVATIVE DISCOURSE

4 HYBRIDITY: AS FORM AND STRATEGY

5 SAMAS AND HYBRIDITY

6 THE HISTORICAL STRATEGY OF INDIAN POSTCOLONIAL THEORISTS

7 SUBALTERN STUDIES

8 SUBALTERNS OF THE SUBALTERNS: ENGENDERING NEW KINDS OF HISTORY AND POLITICS

25 Women, Gender and Anti‐colonialism

1 THE ROLE OF WOMEN IN THE ANTI‐COLONIAL MOVEMENTS

2 THE RELATIONS OF FEMINISMS TO THE IDEOLOGIES OF THE FREEDOM STRUGGLE

3 SOCIALISM

4 MODERNITY

5 CULTURAL NATIONALISM

6 THE PROBLEMS FOR FEMINIST POLITICS AFTER INDEPENDENCE

26 Edward Said and Colonial Discourse

1 DISCOURSE AND POWER IN SAID

2 THE OBJECTIONS TO ‘COLONIAL DISCOURSE’

3 DISCOURSE IN LINGUISTICS

27 Foucault in Tunisia

1 FOUCAULT’S SILENCE: SIDI‐BOU‐SAÏD AND THE CONTEXT OF

THE ARCHAEOLOGY

2 DISCOURSE IN FOUCAULT

3 THE DISCURSIVE FORMATION

4 THE STATEMENT

5 THE REGULARITIES, THE ENUNCIATIVE MODALITIES AND FORMATION OF OBJECTS

6 THE HETEROGENEITY OF DISCOURSE

7 DISCOURSE AND POWER IN

THE HISTORY OF SEXUALITY

8 A FOUCAULDIAN MODEL OF COLONIAL DISCOURSE

28 Subjectivity and History

1

WHITE MYTHOLOGIES

REVISITED

2 MAKE THE OLD SHELL CRACK

3 STRUCTURALISM, ‘PRIMITIVE’ RATIONALITY AND DECONSTRUCTION

4 PILLAR OF SALT

5 THE MARRANO: ‘A LITTLE BLACK AND VERY ARAB JEW WHO UNDERSTOOD NOTHING ABOUT IT’

Epilogue: Tricontinentalism, for a Transnational Social Justice

Letter in Response from Jacques Derrida

Bibliography

Index

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Pages

iii

iv

v

ix

x

xi

xii

xiii

xiv

xv

xvi

xvii

xviii

xix

xx

xxi

xxii

xxiii

xxiv

xxv

xxvi

xxvii

xxviii

xxix

xxx

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

13

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

71

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

159

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

304

305

306

307

308

309

310

311

312

313

314

315

316

317

318

319

320

321

322

323

324

325

326

327

328

329

330

331

332

333

334

335

337

338

339

340

341

342

343

344

345

346

347

348

349

350

351

352

353

354

355

356

357

358

359

360

361

362

363

364

365

366

367

368

369

370

371

372

373

374

375

376

377

378

379

380

381

382

383

384

385

386

387

388

389

390

391

392

393

394

395

396

397

398

399

400

401

402

403

404

405

406

407

408

409

410

411

412

413

414

415

416

417

418

419

420

421

422

423

424

425

426

427

428

429

430

431

432

433

434

435

436

437

438

439

440

441

442

443

444

445

446

447

448

449

450

451

452

453

454

455

456

457

458

459

460

461

462

463

464

465

466

467

468

469

470

471

472

473

474

475

476

477

478

479

480

481

482

483

484

485

486

487

488

489

490

491

492

493

494

495

496

497

498

499

500

Postcolonialism

AN HISTORICAL INTRODUCTION

ANNIVERSARY EDITION

Robert J. C. Young

This edition first published 2016© 2016 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd

Edition history: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. (1e, 2001)

Registered OfficeJohn Wiley & Sons, Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

Editorial Offices350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148‐5020, USA9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UKThe Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley‐blackwell.

The right of Robert J. C. Young to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and authors have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services and neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for damages arising herefrom. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging‐in‐Publication Data

Names: Young, Robert J. C., 1950– author.Title: Postcolonialism : an historical introduction / Robert J. C. Young.Description: Chichester, West Sussex, UK ; Malden, MA : John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.Identifiers: LCCN 2016025068 (print) | LCCN 2016031249 (ebook) | ISBN 9781405120944 (paperback) | ISBN 9781118896853 (Adobe pdf) | ISBN 9781118896860 (epub)Subjects: LCSH: Postcolonialism–History. | Postcolonialism–Philosophy. | Colonies–History. | Imperialism–History. | Revolutions–History. | Anti‐imperialist movements–History. | Developing countries–Politics and government.Classification: LCC JV51 .Y68 2016 (print) | LCC JV51 (ebook) | DDC 325/.3–dc23LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016025068

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

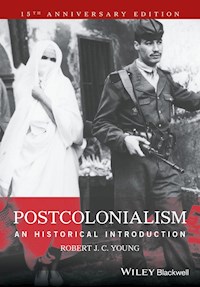

Cover image: A French soldier on patrol in Algiers, during the war of Algerian independence, 1962.Photo: Stuart Heydinger, The Observer / Hulton Getty

In memory of my fatherLeslie William Young1919–2000

Thy loving kindness shall follow me all the days of my life

Preface to the Anniversary Edition

I THE NOMOS OF POSTCOLONIALITY

This book is concerned with the revolutionary history of the non‐Western world and its centuries‐long struggle to overthrow Western imperialism: from slow beginnings in the eighteenth century, the last half of the twentieth century witnessed more than a quarter of the world’s population win their freedom.1 It was written before the momentous political events of the twenty‐first century: published two months before the 9/11 attacks in 2001, and ten years before the Arab revolutions that erupted across the Arab world in 2011.2 It had been originally commissioned as an introduction to postcolonialism at a time when “postcolonial theory” formed an innovative body of thinking that was making waves beyond its own disciplinary location. That interest was the mark of a new phase within many Western societies in which immigrants from the global South had begun to emerge as influential cultural voices challenging the basis of the manner in which European and North American societies represented themselves and their own histories. The late Edward Said and Stuart Hall both symbolized the ways in which intellectuals who had been born in former colonies became spokespersons for a popular radical re‐evaluation of contemporary culture: a profound transformation of society and its values was underway. That revolution involved the consensus of an equality amongst different people and cultures rather than the hierarchy that had been developed since the beginning of the nineteenth century as a central feature of Western imperialism. Postcolonial critique has been so successful that by the beginning of the twenty‐first century the concepts and values of postcolonial thought have become established as one of the dominant ways in which Western and to some extent non‐Western societies see and represent themselves.

Although the basis for such arguments was generally the colonial experience, it has also been argued that such postcolonial critiques were also preparing the way for the transformation of society that was being produced by the demands of globalization.3 The celebration of difference became the activity of corporations as well as university professors. What this critique misses, however, is the possibility of different forms of difference: whereas state ideologies of multiculturalism employed traditional ideas of identity as a positive category in order to accommodate diversity, postcolonial intellectuals were rather spearheading a critique of the propagation of multiculturalism as an official ideology, employing a concept of difference as a non‐positive term whose value was inherently translational to challenge the very concept of fixed identities. Multiculturalism was a product of continued nationalist thinking, whereas postcolonial difference emerged as a critique of both.

Postcolonialism, however, goes well beyond the elaboration of issues of identity and difference. In this book, rather than introduce the topic by giving a summary of the ideas and concepts identified with postcolonial “theory”, I chose a different approach: to look at the genealogy of postcolonial theory in terms of its relations to earlier political and intellectual movements resisting imperialism and the cultural dominance of the West, tracing its origins in the struggles against colonialism in the past. Contemporary postcolonial theory was grounded in the inspiration of the work of earlier activists such as Frantz Fanon, Aimé Césaire, CLR James, Albert Memmi, or even in those who were viewed more critically, such as Léopold Sédar Senghor or Marcus Garvey. As soon as I went back to consider that earlier generation and its very active relation to anticolonialism and decolonization, the vastness of the task opened up before me. For how could one analyse the context of imperialism in the twentieth century without also considering its formation, and the development of resistance to it, in earlier periods? Although there were many books on imperialism, both from a general as well as particular perspectives, and even more books on specific histories of decolonization, there were very few that looked at imperialism and the pressure for decolonization from the colonized’s point of view. Above all, there was no history of anticolonialism—historical or intellectual. In this book I attempted therefore the first history of anticolonialism that would provide the context of centuries of active, political struggle. In order to do that, I made a number of decisions. First, I would offer not a blow‐by‐blow narrative of the historical military and political struggles but rather focus on the intellectual and cultural production that was developed to support and promote anticolonial activism; secondly, instead of attempting an encyclopaedic history of all empires and of resistance to them, I would concentrate on the British and French empires not only because they were the largest in recent history but because together they embodied what might be called the two dominant western models of empire, of indirect rule and assimilation; third, that I would emphasize the constructive nature of the cultural and intellectual movements that accompanied the political processes of decolonization, and would not extend discussion to the subsequent history of the various countries after independence. This last choice was made partly pragmatically for reasons of space, but also because I wanted to present a different emphasis and perspective on the anticolonial movements than the commonly‐voiced criticisms of postcolonial countries (usually made by people from the former colonizing countries) for not living up to the challenges of independence. Perhaps some did not, but that was a separate story. What I wanted to convey instead was the excitement of the intellectual productivity of the time, the sense of its radical potential and its dynamic political aspirations for transformation that could continue to offer political inspiration into the future.

In a book that attempted such a comprehensive history even within those limited terms, inevitably much is missing, or receives less emphasis than I might now wish. One argument that is certainly represented but which could be made more strongly throughout is the simple fact that Western imperialism, as it was developed systematically in the course of the nineteenth century, was a race imperialism. First advanced as an ideological justification for slavery, the claimed racial superiority of those of European origin then came to underlie both the assumptions and justifications for imperial rule. In that context, Nazi Germany operated as a more extreme and systematic form of the fundamental racialism of all imperial powers; the difference was that it was applied to Europeans. Although racialism as state ideology was discredited after the Second World War, it was not until the 1980s that it was challenged at a broad cultural as well as a social level. By that time most empires had been disbanded, most colonies abandoned. Postcolonialism was then to effect the death‐knoll of still surviving imperialist ways of thinking about racial and cultural difference in Europe and North America. In all but one domain, it might be argued: while society changed, international politics continued according to the old assumptions. The mark of that split was the war on Iraq, carried out in the face of the widespread opposition of the populations of those countries that initiated it, and whose aftermath we are still suffering today. Even there though, that war demonstrated a significant change: whereas when British Indian troops invaded Iraq in 1919, they were more or less able to control the country in a few weeks, today Iraq is scarcely a single country anymore and will probably never return to its former national identity. In the latter half of the twentieth century, and the opening of the twenty‐first, dominating states that invade or occupy the territory of other peoples have found it almost impossible to generate a culture of consent to being ruled: whereas in earlier times, there would be a pragmatic form of acceptance interrupted by periodic rebellions, today occupied countries are typically almost uncontrollable.

While physical resistance to the violence of colonial invasion was there from the beginning and continued to the very end, indigenous people developed many other forms of resistance to established imperial rule through political organization and cultural empowerment. It was this political and intellectual tradition that provided the resources for the development of postcolonial thought. The object of this book was in part to document and demonstrate the richness and diversity of that intellectual production, to be found in almost all colonies on earth. The most influential in terms of today’s thinking came from the French tradition in the work of the Senghors, Césaire, Memmi, and above all Frantz Fanon. As in all anti‐colonial thought, this was developed in dialogue with dissenting Western intellectuals, creating the basis of a global culture of dissent.

In writing the complex and multifarious political history of empires and anticolonialism the major challenge for me, apart from researching such a vast range of material, was how to organize it. It was only some time into the writing of the book that it became clear to me the degree to which the Bolshevik Revolution had functioned as a fulcrum for the development of anticolonial politics. After 1917, most activists, with the notable exception of Gandhi, turned to a secular Marxism for inspiration and strength, without, however, for the most part treating it as reverentially as the functionaries of the Comintern expected and required. This rich texture of dissent within the Marxist anti‐colonial tradition occupies much of the material of this book. I continue to believe that this overall historical model remains accurate, and makes most sense of the developments of anticolonial thought and practice around the world in the twentieth century. The socialist experiment that then emerged out of the anticolonial movements was for the most part defeated, typically as a result of the use of oppressive forms of social engineering that contributed to the gradual reversal of the left over the course of the Cold War. It was quickly replaced with the globalization to which almost every independent nation‐state on earth has now been forced to submit. Only South America has successfully charted a relatively different course: as Islam has taken over from communism as the number one enemy, the “Latin” states have been allowed a new freedom. Whether some of them will succeed in developing a socialism driven by consent rather than coercion remains to be seen. For its part, the role currently being played by Islamists of resistance to the power of the West draws on a movement that began in the nineteenth century but which was deflected for many decades by the development of secular communism and nationalism after 1917. The work of Faisal Devji and Olivier Roy, in my view, has provided the best perspectives for understanding contemporary Islamism since 2001.4

It has been objected that postcolonial thought is not Marxist as such, even including those who self‐identity as “materialist” postcolonialists. But postcolonialism is Marxist in exactly the same way that anticolonial thought was, that is, disjunctively. It assumes the broad foundation of the deep residual connections between capitalism and imperialism, but focuses instead on specific issues of significance, such as racial discrimination, for those on the receiving end of imperial ideology, not just the workers but all those minoritised and rendered “subaltern” by continuing colonial power structures, whether in the West or the non‐West. In the 1960s, after the decline of the Soviet Union under Stalin and the 1956 invasion of Hungary, China and Cuba functioned as the inspiration for leftist anti‐colonial activists, especially when they became aware that Mao Zedong had heretically substituted the peasantry for the proletariat. Inexplicably, anti‐colonial activists were undeterred by the 1949 Chinese recolonisation of Tibet; they should have taken that as a warning, even if at the time they were unaware that China was no less oppressive in its treatment of its own people than the Soviet Union. Today, the effects of globalization and climate change have caused the peasantry in whose name they fought to drift to city slums and to migrate across continents: in its preoccupation with all the issues surrounding contemporary forms of migration, itself a product of the global inequity between different societies, the postcolonial focus remains continuous with the political priorities of the past.

If I was writing this book today, therefore, I would not change its fundamental historical narrative, but inevitably reflecting on its contents I have become more aware of what this book did not broach as effectively as I should have liked. The first issue concerns its mode of presentation: while the story it tells presents the history of imperialism and anti‐colonialism as a complex narrative developing out of different sites, it does not allow enough for the ways in which that history involved different and contradictory temporalities. It is not as if there was a uniform chronology by which colonial and imperial rule were then simply followed by independence. While this may be relatively (though rarely wholly) true in the case of any individual colony, collectively these individual narratives had a much more multifaceted relation to each other. Complicating this further, was the contemporaneous history of the Ottoman Empire which predated the modern European empires and was only dismembered by them in 1919. I would now argue that the Ottoman Empire was far more significant than I allow for in this book; its gradual disarticulation was also, I would now suggest, also far more far‐reaching. Palestine, along with Tibet, one the last remaining colonies on earth, exists in the form it does today as part of the continuing legacy of the Ottoman Empire and its recolonization. There are many places, often small islands, around the world that continue to be ruled by other powers, but these could be described at best as historical anomalies. There are also many places where the often somewhat arbitrary process of national formation has produced tensions in particular provinces which never willingly chose to belong to the nation, as in India and elsewhere. Palestine, on the other hand, is rather different.

The case of Palestine also points to a theoretical development that has taken place since this book was written, namely the study of settler colonialism as a form of colonialism distinct enough to deserve analysis as an entirely separate category.5 While I distinguished between settler colonies and exploitation colonies in this book, I did not separate them out as much as I would do now in terms of the diverse dynamics that obtained in each. The difference between them emerges particularly at the point of decolonization, where in the case of the settler colony power is handed to the colonial settlers, while the indigenous people are offered no possibility of self‐realization and often, in fact, find themselves subjected to worse conditions than those under imperial rule, as was largely the case in the Americas and Australasia. A major continuing problem of colonialism today is that of settler colonies and their relation to indigenous peoples. Palestine is a different case, first because it was colonized in twentieth century, and second, because it was colonised by people with a historical counterclaim to indigeneity. The politics of Palestine are made apparently irresolvable by the competing interests of two different, though ethnically intimately‐related, groups with similar demands split by 2000 years of history. If it were just that, then Palestine might look little different from the many other regions of the world in which there is ethnic conflict of one kind or another, for example Fiji. What makes it different is the position of the state of Israel with respect to the Occupied Territories which is more imperial than colonial. The illegal continuous development of the settlements in the Occupied Territories points towards a larger imperial project of expanding the boundaries of Israel not only to the full extent of the Occupied Territories but from there perhaps, according to the Zionist ideology of Eretz Israel, to territories in Jordan and elsewhere. Only an imperial project of territorial enlargement can explain the ever‐continuing program of settlement expansion, and the inhuman treatment of the indigenous Palestinian population of the Occupied Territories. With the Israeli treatment of the Palestinians, forced to live behind the towering concrete separation walls, deprived of their land and water, denied access to the roads that have been built across their land, not even allowed to travel freely from one town to another, contrast the treatment of the Jews who, with some significant exceptions, lived in relative peace and prosperity throughout the Ottoman Empire and its predecessors for over one thousand.6

II END GAME FOR THE NOMOS OF THE EARTH

The colonization of Palestine since 1948 could be said to represent the contemporary world order just as much as the figures of the migrant and refugee that it produced. Despite the emphasis in this book on the role of the Bolshevik revolution, from a different perspective, the colonization of Palestine might also be taken as the fulcrum between the older narrative of colonization and the development of our contemporary world order. The two were in fact articulated through a curious historical conjuncture: the publication of the Balfour Declaration four days before the Bolshevik revolution of 6 November 1917. The Declaration had been prepared for by the Sykes‐Picot agreement of the year before. Two years later, at the end of the First World War that had precipitated both events, perhaps the largest political reorganization of the world at one time took place with the Treaty of Versailles. According to the German jurist Carl Schmitt, in Der Nomos der Erde im Völkerrecht des Jus Publicum Europaeum or The Nomos of the Earth, in the International Law of the Jus Publicum Europaeum, in that moment the old order of the world came to an end to be replaced by that of modernity. Written in the early 1940s during the course of the Second World War, Schmitt’s controversial work argues that the European basis of international order that had been developed since the sixteenth century had come to an end in 1919.

The traditional Eurocentric order of international law is foundering today, as is the old nomos of the earth. This order arose from a legendary and unforeseen discovery of a new world, from an unrepeatable historical event. Only in fantastic parallels can one imagine a modern recurrence, such as men on their way to the moon discovering a new and hitherto unknown planet that could be exploited freely and utilized effectively to relieve their struggles on earth. The question of a new nomos of the earth will not be answered with such fantasies, any more than it will be with further scientific discoveries. Human thinking again must be directed to the elemental orders of its terrestrial being here and now. We seek to understand the normative order of the earth.7

Schmitt’s argument involves the idea that the discovery of the new world was revolutionary because it altered the political geography of Europe to the degree that the world beyond Europe was not perceived as the discovery of a new enemy or enemies, but as the finding of free space, to which the fundamental basis of European law, land ownership, was almost immediately applied. This emphasis on the issue of land, on “das Erde”, opens up a possible ecological narrative from which we could rethink Schmitt’s perspective.8 In his terms, however, this led, soon after 1492, to the development of what Schmitt calls global linear thinking in which the first lines of division, demarcation and distribution were drawn. So in 1494 Pope Alexander VI published the edict Inter caetera divinae which established a line which ran from the North to the South Pole, 100 miles west of the meridian of the Azores and Cape Verde. In the same year, in the treaty of Tordesillas signed between the Spanish and Portuguese, another line was drawn approximately through the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, “in which the two Catholic powers agreed that all newly discovered territories west of the line would belong to Spain and those east of the line to Portugal. This line was called a partition del mar océano...” (89). Since in practice Spain and Portugal were already rivals for the spice islands of the Moluccas, by the Treaty of Saragossa (1526), “a raya [line] was drawn through the Pacific Ocean, at first along what is now the 135th meridian, i.e. through eastern Siberia, Japan, and the middle of Australia” (89). The world was thus neatly divided up between them.

However, it was not long before the supremacy of the first European colonial powers ceded before that of France and England, who established between themselves a different order, known as the amity lines. While the rayas were “internal divisions between two land‐appropriating Christian princes within the framework of one and the same spacial order”, the amity lines that developed in the seventeenth century operated by a completely different principle, namely that “treaties, peace, and friendship applied only to Europe, to the Old World, to the area on this side of the line” (92). The line ran roughly “along a degree of longitude drawn in the Atlantic Ocean through the Canary Islands” to the West and along the equator to the South. On the European side of this line, seafarers were forbidden to attack the ships of other European powers. Beyond that, it was a free for all. “At this ‘line’, Europe ended and the ‘New World’ began” (93). It was this arrangement that allowed privateers and pirates to be informal agents of the Kings of France or England, rather than mere outlaws, and brought to trial if they attacked a foreign ship in inappropriate waters, as in the notorious case of Captain Kidd. Beyond these lines, there were no legal limits, and only the law of the stronger applied. As Schmitt describes it, mutual enmity between European powers was thus distinguished from absolute enmity with respect to non‐European powers, setting limits to war, limiting conflict to that between sovereign states and at the same time preventing their mutual destruction. The appropriation of global space was organised on the legal basis of an international system of mutual recognition that attempted to assure non‐intervention in each other’s territories, which were at once defined in legal terms as both outside and inside the borders of the colonizing state. This European system of international order on the basis of colonial partition was inevitably modified and developed over time; it began to break down in the nineteenth century, according to Schmitt, and ended in 1919 with the Treaty of Versailles when the New World, by which he meant the United States, became the arbiter of a new Anglo‐Saxon global order. That informal imperialism was consolidated by an unlimited “right of intervention”, supported by the concept of a “just war” that was written into the war‐guilt clause (no 231) of the Versailles Treaty. This accused Germany of having waged a criminal war, initiating a legal category that continues to this day and provides the legal basis for wars of “humanitarian intervention”.

The question that arises in the present context is whether this schema of a normative order of the earth could be reinterpreted or accommodated to work within a postcolonial framework. Could there be a nomos, or law, of postcoloniality, less in the sense of a strict legal foundation than an enabling model that defines postcoloniality itself? How could such a model or theory take into account the temporal, enfolded, palimpsestic complexity of the postcolonial? Can we think it in the way that we can understand and interpret the shifting multiplicity of historical times? The choice would seem to be either to restrict and simplify our understanding of what the postcolonial involves, excising a large part of what historically strictly speaking counts as postcolonial, or rethinking our concept of it, particularly with respect to its relation to a narrative of the nation according to the linear, progressive sequence from colony to nation. In practice, that narrative often folded back on itself. It was not just that colonies became nation states: rather colonies became nation states which themselves in turn became colonizing powers.

Returning to Schmitt, we can observe that the major intervention made by the United States at the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 was the introduction of the principle of national self‐determination, already instituted into Bolshevik constitutions, which could be seen as the basis for the eventual transformation of the world into its current state of postcoloniality, even if the idea of a nation being able to determine itself has proved to be largely a nationalist fiction. It was also largely a theoretical fiction at Versailles, where the US was not yet politically powerful enough to control Britain or France. Woodrow Wilson did manage to veto Clemenceau’s desire to break Germany up into smaller states, and some European states were allowed self‐determination, specifically Eastern European ones such as Czechoslovakia and Poland that were liberated from either German or Russian imperial control, the immediate result of which was a huge refugee crisis. Beyond Europe, however much Wilson’s new principle raised hopes and led to delegations such as that of the African National Congress travelling to Versailles, in practice Wilson was largely outmanoeuvred by Lloyd George and Clemenceau who used the treaty to expand the British and French empires to their greatest ever geographical extent, primarily by appropriating the German empire in Africa and the Pacific and, in the Treaty of Sèvres that followed in 1920, by dividing up the Ottoman empire between themselves, as already agreed in 1916. Substantial colonial gains were also made by Belgium, Portugal, South Africa, Australia, New Zealand and Japan. The land‐grab of the Ottoman Empire decided at the Treaty of Sèvres suffered a setback when the nationalist Turkish general Kemal Atatürk resisted the appropriation of most of what is modern Turkey by Greece, France and Italy: the existence of Turkey more or less in its modern form was then acknowledged by the 1923 Lausanne Treaty. The only non‐European independent states that had been created out of Versailles and Sèvres, Armenia and Kurdistan, disappeared at Lausanne. Arguably the Treaty of Versailles signalled the creation of a new world order with the formation of the League of Nations, with all reallocated colonial territories authorized by its mandate. Although the League had been partly an American idea, the US Congress refused to pass the terms of the Treaty of Versailles with the result that the US never joined the League of Nations (which Schmitt, for his part, considered worse than anarchy). This forms the basis for Schmitt’s critique of the position of the US, namely one of economic and military power but political isolationism. All that would change, of course, in 1945, which in some sense operated as a final ending of the European war and initiated the period of global decolonization and new forms of political and economic domination that continue to the present.

Schmitt’s argument, however much propelled by his anti‐liberal propensities and German perspective, operates as a powerful paradigm for the historical advent of the postcolonial world. Schmitt, of course, does not call it that: having hoped that the new Europe of Nazi Germany would represent the beginning of a new nomos of the earth, by 1950 he ends with three possibilities for a new nomos: the perpetuation of the Cold War balance of power between the US and USSR; an expansion of earlier English hegemony to include the US which would effectively develop the new form of Anglo‐Saxon hegemony of Versailles; or a new balance of power in which “a combination of several independent Großräume or blocs could constitute a balance, and thereby could precipitate a new order of the earth” (355). At the moment, arguably, we are poised between the second and third: the question about globalization is exactly that: does it name a new hegemony of American empire, or is capitalism, which has no interest in national political objectives, in the process of producing a new order of the world in which power is distributed and no single block hegemonic?

From a postcolonial perspective, the interesting aspect to Schmitt’s argument is that the New World replaced the Old as the centre of hegemonic power. The New World, whose control by Europe signalled the nomos of the Jus Publicum Europaeum for over 400 years, took control, bringing us into a postcolonial era which we can call the postcolonial nomos of the earth. If 1919–1945 functions as the fulcrum point for the transfer of power to the USA, we could say that the nomos of the earth moved from European juridical law to international European juridical law enforced by the power of a former British settler colony.

III ENFOLDED POSTCOLONIALITY AND EXPORT OF PEOPLE

Even with the shift of power that he describes, Schmitt still assumes the perpetuation of one major institution of colonialism that was indeed to survive the process of decolonization, whether peaceful or violent, more or less intact, the institution that underlies his whole schema: that is the law itself. As a result of imperialism (British, French, Arab) there are effectively just three legal systems being practiced in the world today, i.e. French Napoleonic (civil code), British common law, or Muslim Sharia law. The continuity with former imperial interests is everywhere almost exact: for example the United States practices common law in every state except Louisiana, which uses the Napoleonic civil code, as does Quebec. The world is divided up between these three systems, or a bijuridical mix between them. The majority of countries in the world use civil or common law which means that, despite decolonization, the world today remains dominated by European law. The Jus Publicum Europaeum remains in place, the most powerful and the longest‐lasting legacy of colonialism. From one perspective we could see colonialism and imperialism themselves as slow mechanisms designed to impose a universal legal system on the world and thereby to achieve a world order. This has been particularly successful from the point of view of capitalism, since it provides and constitutes the context in which all international trade takes place. At the same time, less successfully, it constitutes the basis for world political order and the institution of human and other rights.9

From Schmitt’s long‐term perspective that focuses on the legal order, there has, in a certain sense, been a single narrative for the world. In the same way, the postcolonial paradigm is often typically progressive and sequential, conforming to the dominant mode of synchronic time. The nation and narration narrative, for example, posits the nation as the aspiration of the colonized state, with the story of the nation beginning either in the precolonial era or with the anticolonial activism that preceded its modern form. Against this and Schmitt’s schema, scholars have begun to think of the postcolonial as a form of differentiated, disordered time, rather than as a single entity. The text of colonial and postcolonial history can be read as a changing palimpsest with the different layers simultaneously reacting with and from each other, however anachronistic that might at times appear to be, rather than evolving as a single narrative. To this must be added the paradox that the very formation to which the colony usually aspired, namely the nation state, was itself a form that emerged most successfully through the construction of colonial power. The other side of colonialism and imperialism as the vehicles for the formation of international law could be said to be colonialism and imperialism as the vehicles for the formation of nation states. Viewed globally, however, the relation between colonies and nation states does not form a simple sequence, in which one follows on from the other. Postcolonial critique emphasizes the fundamental role of colonialism and imperialism in the formation of the institution of the nation state itself as it was developed in Europe, not simply the fact that colonies became nation states. While the distinctive characteristic of such colonialism was that race functioned as its primary ideological legitimating and organizational category, this involved a negative extension of the ideological formation of the nation‐state of the colonizing power on the basis of racial and ethnic identification.

This sequential relation of colony to nation in the narrative of decolonization may work for individual nations, but overall it does not pay attention to the historical complexity of nation‐state formation. While there are many arguments among historians and others about which country or people formed the first nation, a concept that can be defined in many different ways, the treaty of Westphalia of 1648 is generally reckoned to mark the advent of the sovereign nation‐state in its modern legal form. The apparent paradox here is that the earliest postcolonial nation‐state was European, not American as one might assume, namely the Netherlands, which seceded from the Spanish Empire in 1648. The first nation‐state to achieve independent sovereignty was a former colony—an act of decolonization that preceded the formation of the USA by over a century. The seven provinces that became the Netherlands had formed part of the Hapsburg Spanish Empire which, under Phillip II of Spain, had attempted to suppress Dutch Protestantism. The Dutch responded with the 1581 Act of Abjuration, one of the sources of the American Declaration of Independence. In the struggle that followed, the Portuguese closed their ports to Dutch traders, which encouraged them to develop their own trade with the east and eventually to commandeer Portugal’s trading posts. By 1648, the Netherlands was a fully‐developed colonial power, trading as far as Japan, operating through the Dutch India Company (Vereenigde Oost‐indische Compagnie, VOC), a huge multinational corporation that, like the British East India Company founded two years earlier, operated with many of the powers of a conventional state, including military forces. Four years later, in 1652, the Dutch established their colony in South Africa. The significance of this history is that the first independent European nation‐state was, first, a former colony, and second, was already itself a colonial power even before its decolonization. Colonialism and postcolonialism were thus developed as part of the same process: even in the period of modern European empires, postcoloniality began over three hundred and fifty years ago. From 1648 onwards, decolonized nation states would almost always transform themselves into colonial powers. Colonialism and postcolonialism have operated together in a structure whereby the former produced the latter which in turn produced more of the former.

The history of the Netherlands illustrates the way in which one typical feature of the nation was that once created, it sought to absorb or acquire more territory beyond its boundaries. Historically the effect of the formation of the postcolonial nation was to produce more colonialism, the colonized became the colonizer. Many nation states, from the Netherlands in the seventeenth century, to the USA in the eighteenth, to Germany and Italy in the nineteenth, developed their prosperity through this colonizing method, an advantage that was not available to most of the 150 odd postcolonial nations that have been established since 1945. Only Israel has operated according to the traditional model of the new nation state’s progressive colonial expansion and the subjugation of the indigenous people. It could be argued, however, that many other nation states have continued this “colonial” model of expansion, though in a very different form. Another way of thinking about the colonial enterprises which enabled nation states to develop economically is that fundamentally they were exporting people: on the one hand the British Empire involved the conquest of territory; on the other hand, a different perspective would be to consider the fact that between 1500 and 1900, some 20 million people emigrated from the British Isles, one of the largest diasporas ever known.10 The economist John A. Hobson already suggested the intrinsic dynamic relation between nationalism, colonialism, and the export of people, in his classic 1902 study of imperialism, describing colonialism as “a natural overflow of nationality”.11 Today, most recent nation states cannot establish formal colonies for their surplus populations who will also thereby enable economic expansion: what has taken place is a different form of overflow or migration. The millions of people who are moving across or leaving the continents of Africa, Asia, Europe, and America form part of a process that has been intrinsic to the development of the nation state since its formation. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as their nations developed, it was largely Europeans who migrated to the non‐European world by the millions: now it is non‐Europeans who are migrating to the Western world. For Europeans, until the late nineteenth century, there were no immigration laws restricting their freedom to emigrate where they chose—they just arrived. Most of those who migrate today legally or illegally are doing so under pressure of war, economic deprivation, or personal individual circumstances, but then so were the Europeans—think of the Irish, for example, at the time of the Famine. In the nineteenth century, Irish emigrants arrived in Canada or at Ellis Island often in far worse condition than contemporary migrants who land at Lampedusa or Lesbos in the Mediterranean.12 Some of them were so ill they were refused entry. From a different perspective than the one that we are generally given, migrants today are performing what has always been a deep structural activity of developing nation states, adjusted to the fact that there are now few possibilities of the traditional mode of land‐appropriation which in the past enabled this. In the past, empire enabled diaspora in settler colonies whereas today we have diaspora without empire, more as in the historical Jewish model. Given the facility today of sending remittances and retaining global links, it would be an interesting to know whether the second model is any less effective economically than the first, in other words to compare the economic advantages to the home country of traditional empires and their diasporic populations against the economic advantages of modern mass migration. Remittances make up a substantial part of many economies today: some countries are largely sustained by them; how important has the effect of remittances been on the booming economies of the countries that currently receive the largest remittances by value—India and China?

The fact that the nation state both emerges with postcoloniality but also produces further coloniality indicates something of the differentiated temporality of postcoloniality in which apparently contradictory formations from different eras or temporal sequences operate simultaneously. This is not the same as Raymond Williams’ “residual and emergent formations”:13 the point here is more that if the emergent is produced by the residual, such as human rights from slavery, then the residual is also produced by the emergent, such as colonialism and race‐imperialism from the postcolonial nation. This oxymoronic time structure of postcoloniality can be illustrated by considering the different historical formations of decolonization. Taking a somewhat sweeping view, we can differentiate decolonization into three eras, each of which operated in a very different idiom from the others.14 First, the decolonization of the Americas, which for the most part took place in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, second, of the colonies in Europe (the Austro‐Hungarian and Ottoman empires), and the settlement colonies of Europe, a process that dates from the early nineteenth‐century up to the first quarter of the twentieth, and finally, third, the decolonization of the colonies of the global South in the period from 1945 to the end of the twentieth century. The difference between their forms of respective coloniality is highlighted by the fact that many earlier postcolonial states themselves promptly became colonizing ones, producing more colonies that were, for the most part, subsequently decolonized, though sometimes also simply absorbed into their own territories. In this narrative of decolonization, the best known periods are the first and the last.

The first involves the Americas, in the period that Schmitt describes. Colonization began in 1492 but in much of the continent scarcely lasted two hundred years. After 1776, the revolutions in British North America, French San Domingue (Haiti), and then across almost all South American states meant that by the 1820s the first great empires of the Spanish, Portuguese, British and French, had been lost. With the exception of San Domingue, which involved a revolt by the African slaves or former slaves, in every case, these were revolutions by European settlers. For the indigenous people of the Americas, national self‐determination often led to worse treatment by local governments no longer controlled by liberal attitudes in European imperial regimes concerned to enforce equitable treatment for native peoples. None of these postcolonial states were postcolonial in the sense that say, Sri Lanka can claim to be—that is, a formerly autonomous set of kingdoms, where after centuries of colonization a majority of its people have re‐achieved control. That has in turn produced its own problem of the tyranny of the majority. The so‐called postcolonial states of the Americas did not re‐institute power for the populations of the former Aztec or Inca empires. The newly established countries of Brazil and elsewhere may have been post‐colonial in one sense, but were certainly not in another. Indeed, from a modern postcolonial perspective, it is open to debate whether the Americas ever became postcolonial at all. They became independent settler colonies. Can we call these postcolonial? To put it bluntly, does postcoloniality encompass independent settler colonies? Or does the settler nation‐state simply comprise a new form of colonization?

The second phase of decolonization, from 1826 to 1945, is the period that is probably least examined, certainly within postcolonial circles, though in many ways it is one of the most interesting. This period is known, quite rightly, as the age of high imperialism, but it was also at the same time an era of decolonization. One of the political practices of the imperial powers was to enforce decolonization on others. The French defeat by the British in North America and India meant that Napoleon sought to expand the French empire elsewhere. After his failed colonization of Egypt, Napoleon concentrated on creating an empire within Europe, known as the Greater French Empire. It was only after the defeat of the second French empire in 1815 that France initiated its third, with the invasion of Algeria in 1830. While land empires have been more long‐lasting to date than maritime empires—think of the US, Russia, China, India—this was not to be the case within Europe. In occupying Germany and Italy, Napoleon unwittingly initiated the motor for the nation states of Germany and Italy that would eventually follow, and produce, in turn, the European empires of Germany, Italy, and Russia. Napoleon’s eventual defeat by Britain, Russia and the Austro‐Hungarian Empire, meant that monarchical power was re‐imposed for a time upon all of Europe, including France itself. One consequence of this history, within Europe, was that nationalism developed into a powerful political force. The Austro‐Hungarian Empire in particular, despite its liberalism, existed in a state of constant turbulent friction throughout the nineteenth century. The Russian Revolution and the end of the First World War resulted in the dismemberment of the Russian, German and Austro‐Hungarian empires, producing independent Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland (1918) and Finland (1919). To these we should add two better‐known independence struggles in this period: first, the unification of Italy, or Risorgimento, generally considered to have lasted for over a hundred years between 1815 and 1918, which was another major long‐term effect of Napoleon’s adventures (as were the loss of the Spanish and Portuguese empires in South America), while its unification formed the inspiring example for anticolonial activists all over the world until 1917. The other spectacular decolonizing event of the period to 1945 was the partial independence of Ireland in 1922 that followed from the apparently successfully suppressed rebellion of Easter 1916. Nationalism in this period produced not just the decolonization of Europe, but also of the Ottoman empire, which was completely dismembered by 1919, but over the course of the previous century had progressively lost Greece, Bulgaria, Romania, Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia‐Herzegovina, Cyprus, and Egypt. What is interesting in retrospect is that while Europeans powers were expanding their empires around the globe, as an apparent consequence of their racialised thinking, they never seem to have considered that the growing nationalism that was forcing the dismemberment of the Austro‐Hungarian and Ottoman empires would ever spread beyond the boundaries of Europe—even when India rose up in open rebellion in 1857. So the British supported the Ottoman Greeks or Garibaldi in Italy in his unification campaign, at the very same time as the British Empire was being extended across the furthest reaches of the earth in Asia and Africa. Meanwhile Italy, along with Greece, rapidly turned themselves into colonizing and imperial powers. Once again, we find that empire and nation are less in a sequential relation of one producing the other than a discrepant simultaneity of directly antithetical political forms, layered, entangled, reiterated and enfolded palimpsestically upon each other.

Decolonization since 1945 has for the most part followed a very different pattern, with relatively little opportunity for territorial expansion—though this remains a feature that explains, for example, the wars between India and Pakistan, or the way in which the former empire of China continues its attempts to expand its borders to this day.15 As has already been suggested, after 1945 migration has come to substitute as a convenient alternative to the older system of colonial territorial expansion. While this may be a way of exporting population and increasing their economic productivity, the significant difference is that in general migrants do not succeed in controlling the country to which they migrate.