26,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

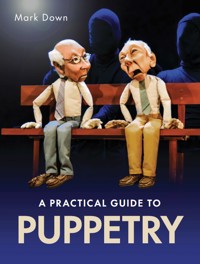

In recent years, puppetry has enjoyed a huge revival on the stages of our theatres, dance venues and opera houses. Large-scale productions such as War Horse and The Lion King have revitalized age-old techniques to attract new audiences and develop the power of storytelling. Puppetry is now seen not only as a specialist art form that exists on its own, but also as a vital tool in the armoury of theatrical storytellers. A Practical Guide to Puppetry offers a comprehensive overview to this versatile art form, exploring established techniques and offering expert instruction on styles from shadow puppetry to group puppetry. Each method is illustrated with practical and accessible exercises, achievable either individually or in a group workshop or rehearsal. With over eighty exercises for improvising, training, designing and directing puppetry, accompanied by 400 illustrations, this new book gives a complete approach to puppeteering with objects, simple puppets and puppets with mechanisms.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 322

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

First published in 2022 by The Crowood Press Ltd Ramsbury, Marlborough Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2022

© Mark Down 2022

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7198 4102 6

Cover design by Sergey Tsvetkov

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION: WHAT IS PUPPETRY?

PART I – TECHNIQUES

1 BRINGING OBJECTS TO LIFE

2 WORKING WITH RODS, STRINGS AND MECHANISMS

3 PUPPETING THE HEAD

4 PUPPETING THE BODY AND LIMBS

PART II – TRAINING

5 BREATHING AND CENTRING

6 FIXED POINT AND FOCUS

7 LEADING AND FOLLOWING

PART III – DEVELOPMENT

8 GROUP PUPPETRY AND IMPROVISATION

9 DESIGNING PUPPETS

10 TALK TO THE HANDS: DIRECTING PUPPETRY

FURTHER RESOURCES

PHOTO CREDITS

INDEX

Acknowledgements

My heartfelt thanks first to Fiona Clift, who has read and discussed and listened and advised and who features in many of the photographs. To Edward Docx, who enthused and encouraged and gave me a non-alcoholic beer at crucial moments. To Caroline Down, Ruth Paton and Giulia Innocenti, who read several chapters and gave helpful feedback. To Philip Haas, Peter Down, Carolyn Choa, my mum Maddy and my brother Jim, who are always supportive.

To Nick Barnes, who founded Blind Summit Theatre in 1997 and with whom I learned everything I know about puppetry. He made many of the puppets in this book. To all the people in the photographs, and behind the puppets in the photographs, whose remarkable work has inspired me for twenty-plus years making puppetry. To the current board of Blind Summit: Eddie Berg, Henrietta Duckworth, Jane Morgan and Wojtek Trjinski.

And I am extremely grateful to everyone who gave permission to use their photographs: Bertha Elizondo, Helen Foan, Antonella Carrara, Edmund Collier, Lorna Palmer, Odetta Riskute, Nick Barnes, Patrick Baldwin, Richard Blomshield, Susanna Neves, Aga Blaszczak, Harry Zundel and Stephanie Wickes.

INTRODUCTION: WHAT IS PUPPETRY?

‘I dream about puppets all night. I see strings on people.’ (Trey Parker)

PUPPETRY IS NOT A SINGLE THING

A little man walks around on a table top complaining about his life, a cast of characters dance in a miniature theatre, a giant Wizard grows mightily into the air in a sports stadium, the shadow of an old lady changes into a bird, a pair of glove puppets fight, a miniature person watching TV is swallowed alive by their sofa, a detective multiplies into five tiny detectives, a firebird flies over the heads of the audience in a concert hall, a pair of red shoes walk up the wall in a dark caravan, two balloons ‘vogue’ to a contemporary soundtrack, a giant ‘Gulliver’ travels into a town on a barge…. Seeing these things is magical. They are puppetry.

There are many types of puppetry and hundreds of different puppets. There are giant puppets and tiny puppets. There are puppets that require lots of people to operate them and puppets that can be operated on one finger. Some puppets are beautifully sculpted or painted, while others may be traditional and rather crude in style. Simple everyday objects, which are not actually puppets at all, can be used by puppeteers to take the shape of living things. Some puppets are controlled by strings, rods, gloves, shadows or remote control, or a combination of all of these, or none of these.

Suki in Citizen Puppet (Blind Summit).

Some puppets work in miniature, others on a giant scale. They appear in theatres, on the street, on specially built stages, in stadiums, at the beach. Sometimes they are part of telling a story. At others they are a special effect. Some are specially invented for a particular show, while others may be part of a tradition that is hundreds of years old.

What all puppets have in common is that the protagonist in the scene – the character that the audience is watching – is played by a something that is not alive: a specialized object; a puppet. It only looks like it is alive because it is being moved by a puppeteer. Puppeteers, working behind the scenes, make everything happen.

However, the fact is that none of these things have happened at all. It just looked like they happened.

PUPPETRY IS AN ILLUSION

Puppetry is a kind of magic trick. The puppeteer brings life to an object that the observer knows is not alive. As with magic, the excitement for the people in the audience lies in whether the puppeteer can convince them with their skill. Can they make them see the puppet come alive? Can they make them believe it is alive? The trick is everything. Just as we know that there is no such thing as magic – it is a trick – we are all too aware that a puppet is not actually alive. But….

Where magic is about ‘misdirection’, puppetry is about ‘direction’. While the magician tries to make the observer look away, so that they can do the trick without being seen, the puppeteer encourages the audience to look at the puppet and to see the trick. Puppetry is a magic trick done in plain sight.

When a magician pulls a live rabbit out of a seemingly empty hat, or a puppeteer makes fur move so that it looks like a living animal, the event happens in the imagination of the audience. Watching a magic act, the audience sees a non-existent rabbit magically come into existence, apparently out of nothing. Watching a puppeteer, the audience imagines that the fur is moving on its own and is able to overlook the fact that it is the puppeteer who is doing it.

Puppetry is the art of moving something with your hands so that it looks like it is moving on its own – like it is alive.

DUPLICATION

There is a difference between what the puppeteer does and what the audience sees. In puppetry, everything is duplicated. There is the puppet’s world and the puppeteer’s world. There is the puppet’s head and hands and feet, and the puppeteer’s head and hands and feet. There is the puppet’s action and the character’s action, and the puppeteer’s action. There is what the puppet does, what that looks like, and what it means. And there is what the audience sees and what the audience understands from what it sees.

It would be wrong to say that the puppeteer ‘does the movement of the puppet’; they do not. There is a difference between the movement that the puppet does, and the movement that the puppeteer does to make the puppet do that movement. The puppeteer makes the puppet move using their hands. When the puppeteer moves their hand holding the puppet’s head, what the audience sees is the puppet move its head.

Consider a glove puppet picking something up. It bends over, it reaches out for the item, and it picks it up. At least, that is what it appears to do and that is what the audience understands it to have done. What actually happened, of course, is that the puppeteer made the puppet appear to bend over by flexing their hand. The puppeteer then moved the puppet in such a way that it appeared to reach out, then moved it again so that the puppet appeared to pick up the item in its arms. Actually, it was the puppeteer who picked it up in their hand.

The puppeteer’s hand holds the Rubik’s Cube in the puppet’s hand.

Furthermore, different puppets would do it in different ways. A string puppet picks something up using a string rigged to pull into its hand. A three-person table-top puppet picks something up using the puppeteer’s hand. In a shadow show, the item might be controlled on another stick, or the puppet might be swapped with another puppet that is already holding it, and so on.

What the puppeteer does, what the puppet does and what the audience sees are all different.

THE VIEW OF THE AUDIENCE

What this all comes down to is that there are two points of view in puppetry: the view from in front and the view from behind. The audience sees the puppet from in front and the puppeteer sees it from behind. The puppet has no point of view.

If the show is to be understood, it is the view of the audience – the view from in front – that matters. What the audience imagines the puppet is doing when they watch the show is what the puppet is doing. If they do not understand what the puppeteer wants them to see, and if they do not see what the puppets do, then to all intents and purposes it might as well never have happened.

Throughout this book, the audience – that is, the person watching from in front of the puppet –is the arbiter of ‘what happened’. What the puppet thought and did is what the audience believes it thought and did. What the audience sees and hears, and what they interpret from that, is what happened. There is no other view.

The only ‘truth’ in puppetry is what happens in the imagination of the audience.

PUPPETS ARE OBJECTS THAT PERFORM

A puppet of a dog walks on stage and the audience gasps. It looks just like a real dog, they say. It is more real than a real dog.

Notice that they do not say that they think it is a real dog. They are not fooled by it. They don’t make that mistake. But they do say that it is even more real than a real dog.

It is more real than a real dog because it is acting. In other words, it is not behaving like a real dog at all, but like an acting dog. It is like a dog that has learned its lines and rehearsed beforehand. A real dog would bark at the audience, wag its tail, come and go as it wanted, lift a leg on the stage, and so on. A puppet dog does not do this. It is there to serve the story. It moves in sympathy with the storytelling, it learns and repeats the role, it listens and thinks and moves as the director directed it. It might even talk. It gives a written performance, like a dog actor.

Although, of course, it is not the dog that does it; it is the puppeteers.

SEEING THE PUPPETEER’S WORK

Although they do not realize it, the audience is really there to watch the puppeteers, not the puppets. As soon as someone sees a puppet, they know that there is someone behind it – or above or below. The puppeteers may or may not show their faces, or even appear on stage, but the audience knows they are there. The observer may or may not talk about the puppeteers – they may only talk about the puppet – but they know that the puppet did not do it on its own.

Without a puppeteer, a puppet is an incomplete object. Whether it is lying in a box or hanging on a hook, its joints will be floppy and its body will not hold it up. It may not have legs or hands; it may be just a pile of rags and a lifeless head. Without the puppeteer, the puppet cannot even stand up. It is only half there. The puppet becomes complete only when the puppeteer picks it up and brings it to life.

The puppet takes the physical space of a character in the show. The puppet is what the audience watches, but it is the puppeteer who learns the role and who makes the puppet do the performance. Equally, it is the puppeteer who is nervous before the show and who may be inspired in the performance.

And it is the puppeteer’s work that the audience comes to see, mediated through the puppet.

THE DISAPPEARANCE OF THE PUPPETEER

When a puppet ‘comes alive’, in fact it does not change at all. It is the puppeteer who changes.

When a puppeteer brings a puppet on stage in a box, they are a person with a box. If the audience does not know what is in the box, they do not know whether the person is a puppeteer or not. They cannot say any more at this point.

If the puppeteer goes on to open the box and take out a puppet, then the audience will assume that they are a puppeteer, and that they are going to make the puppet come alive. To the audience, the person is a puppeteer, out of character, holding their puppet. (They could be wrong, of course. For example, if the person gives the puppet to someone else and leaves the stage, the audience might guess that they are in fact a stage manager or the puppeteer’s roadie. However, the result is the same.)

Then, in order to bring the puppet to life, the puppeteer goes ‘into character’ as a puppeteer and begins to puppet it. The puppet comes alive and the audience no longer looks at the puppeteer. Although the puppet remains unchanged by all these developments, the puppeteer has gone through a series of changes.

Puppeteers do puppet shows, not puppets.

Three states of a puppeteer.

MOVEMENT: THE LANGUAGE OF PUPPETRY

The only thing a puppeteer can make a puppet do is move. Movement is the most basic sign of life. Animation is the absolute essence of a living thing. Through movement, the puppeteer can make the puppet appear to breathe, look about, walk, run, jump, see things, hear things, touch things, think and feel. Through movement, the puppets can appear to meet other puppets, to talk, to get into an argument, to fall in love. Movement transforms the puppet in the mind of the audience into a living thing.

A SPECIAL STAGE

When a string puppet performs on the street, as it comes alive, the world changes from a human world into a puppet world. The street stops being a street and becomes a stage for the puppet to perform on. The real elements behind the puppet – like the puppeteer’s legs or body, a wall, shop-fronts – change into a landscape in which the puppet exists. They become a backdrop for the puppet. The onlookers are now watching a tiny person in a giant world.

If an audience member looks up at the puppeteer, the puppet becomes a puppet again. The puppet stage disappears and the world goes back to normal. Now they are watching a person with a puppet.

The puppeteer kills the puppet, and the puppet kills the puppeteer.

PUPPETRY IS TOTAL THEATRE

When someone decides to put on a show with puppets, they are making a highly eccentric choice: to tell a story with things that are not alive. The aim is to create a world where those items can come to life and tell the story.

To do this, they need to think carefully about the sight-lines, the text, the lighting. They must control where the audience is looking, to direct them to watch the puppets, and not look where they do not want them to look: at the puppeteer. The audience needs to be taught about the conventions of the puppetry of each show: how to watch the puppets, how to interpret their movement, and how to understand what they mean. The creator of a puppet show must recreate every aspect of theatre for the puppets.

Puppets do not go to the theatre. Puppets do not watch puppet shows. A puppet show is done by people who show puppets to other people.

A puppeteer needs to be able to make a puppet look like it is thinking, or walking, or talking; like it has ambition, or is falling in love, or learning to ride a bicycle – whatever the story needs the audience to see them doing – because the audience will only understand what the puppet is doing if the puppet looks like it is doing it.

How to do that is what this book is about.

PART I – TECHNIQUES

1

BRINGING OBJECTS TO LIFE

A puppet is an object that is used to do puppetry. It can take almost any form. It may be a simple, non-articulated, single object or a complex, multipart construction made up of lots of objects held together with joints. It may be an ordinary, everyday object, such as a spoon, a piece of newspaper or a cardboard box, which has another purpose outside of being puppeted, or it may be a specialized object that is recognizable as a ‘puppet’, which has no purpose other than to be puppeted in a puppet show.

He Liyi and his father in Mr China's Son (Blind Summit).

In this chapter you will work with simple, everyday objects, and learn how, by moving them, you can change them into puppet characters. You will learn to give them life, character, emotions, thoughts and joints, simply by moving them, so that they transform into living characters.

The objects do not of course actually 'come alive', except in the imagination of the viewer – your audience. For this reason, these exercises put equal emphasis on your role as an audience, in seeing how the objects change, as on your role as a puppeteer, in moving them. As you do the exercises, make sure that you also practise becoming a good audience, as well as a good performer. Watching puppetry to see what works and what does not work is as valuable in learning how to do it as is actually doing it.

You can practise these exercises on your own, with someone else, or in groups. It is always best to have someone who can watch you doing them, and whom you can watch. You can use any kind of objects or puppets that you are able to handle on your own.

MEETING AN OBJECT FOR THE FIRST TIME

(Adapted from a lesson with puppeteer Steve Tiplady.)

When you first pick up an object, before you start moving it, you may not be able to see any potential in it. However, as soon as you start to play with it, and make it move, features will begin to appear: first, eyes, then a head, then a body, and so on. This exercise is a structured ‘free exploration’ of objects to see what emerges when you start to move them around. There are no ‘wrong’ puppets and no ‘wrong’ ideas: you try things and see what comes. You ‘coax’ characters out of the objects.

This is a really good way to approach an object, or puppet, when you pick it up for the first time. You can use it in exploratory workshops, for devising material and in trying to find the character of a puppet.

The Exercise

Everyone chooses an object and sits in a circle on the floor. The object can be anything you like: a pen, keys, a phone, a cup, a box, a piece of screwed-up paper, glasses, a shoe, a jumper, a cloth.

STEP 1: Close your eyes and pick up the object. Explore the object with your hands. See what it feels like. See if it makes any sounds. See if it moves or bends. Shake the object. Squeeze it. Put it against your cheek to see if it is hot or cold. Smell it. What are its material qualities? Does it remind you of anything? Does it stimulate any thoughts or feelings? Try to think of what the object makes you think of other than its purpose.

Choose any object: cup, pen, newspaper, mobile phone, keys… whatever.

STEP 2: Now place the object on the ground in front of you. Keep your eyes closed, bend forwards so you are close to the object, and take a ‘snapshot’ of it by opening and closing your eyes very quickly like a camera. Move a bit further back and take another snapshot.

STEP 3: Open your eyes and look at your object. ‘Focus’ on it.

STEP 4: Put your hand on the object. Don’t move it.

STEP 5: Begin to make the object breathe. Move it gently up and down on the ground and use your own breathing to make the sound of its breath.

STEP 6: The object stands up.

STEP 6. Make the object ‘wake up’, sit up, stand.

STEP 7: Hold a floppy object, such as a set of keys (right) or a sheet of newspaper (far right), with two hands – one at the ‘head’ and one at the ‘feet’.

STEP 7: Now imagine it has eyes. Decide where they are and make it start to look around. It sees where it is. It becomes aware of the floor, the ceiling, the room. It notices the other puppets in the room, but it does not interact with them yet.

STEP 8: Now make your object start to move around. Think about how it moves. Does it have legs? Or wheels? Does it slide on its belly? Or fly in the air? Or hover, or float, or swim? Does it run everywhere? How many legs does it have? Two, four, six, eight? Or 40? Does it stand up to walk, and then lie down when it arrives where it was going? Does it hop, jump, slither, crawl?

STEP 9: Decide where it is. Is it on ground, in the air, or in water? Is it inside or outside? Is it hot or cold? Is it in danger, or in a safe place? All the time make sure you keep it breathing, and looking at things.

STEP 10: Give your puppet a voice. What sort of voice does it have? Where does it come from? Is it loud or soft? Kind, or rough or aggressive? Does it bark, or meow, or hiss, or tweet, or growl? Does it speak or make words? What sort of language does it speak?

STEP 11: Think about what mood your puppet is in. What is it feeling? Is it happy or sad? Angry or relaxed? Frightened? Excited? Aroused? Whatever you see in it, go with that. If you don’t see anything, try something.

Develop the ‘mood’ of your puppet. Make the emotion bigger and bigger. If it is sad, make it cry. Make it wail with sadness. If it is happy, make it laugh, and then roll around with hysterics. If it is angry, build the mood until it screams with fury. Breathe the feeling deeply into the puppet and let the emotion pour out.

STEP 12. Let the room become a madhouse of shouting, wailing, laughing puppets.

STEP 13: Then stop. Turn everything on its head and try the opposite of everything. Turn your object the other way up. Change the mood to the opposite. If your puppet was happy, make the new one sad. If it was angry, make it relaxed. If it was frightened, make it confident. Develop the new emotions until you have another cacophony.

Then relax.

Tips for Doing It Better

Try to form a clear image of the puppet that your object becomes As you get to know the character of your puppet in the improvisation, be as specific as possible with yourself about what it is. Try to visualize it. See where the eyes are, where the head begins and ends, where the body begins, and where the feet are. Think of your object as taking on a ‘skin’ to become the puppet. The puppet will be made up of the object, and imaginary, invisible extra parts. Be clear what part of the puppet your object is and how it moves in relation to the imagined parts of your puppet. When you show it to an audience, this is what they will be looking at, and they will want you to be consistent.

Focus on the head of the puppet – in the first image it is played by the cup, in the second it is the top of the pen.

Keep your focus on the ‘head’ of your puppet Look at the head and make the puppet look at things. Don’t break your focus on the head when you move it around, and make sure you always know what the puppet is looking at.

Things to Notice

You need to work with the natural qualities of your object An object has its own centre of gravity, its own way of moving and responding to impulses, and its own purpose and use. When you puppet it, you give the object a new centre to move around, you change the purpose of it, and you make it breathe and live. And yet the object’s true qualities are still there. A pen, for example, being small and thin, is easy to control but quite hard to see. A chair, on the other hand, being bigger and heavier, is easier to see, but will have its own way of moving, which you will need to work with.

Remember, there are lots of ways to see an object When you first look at it, you might think you know what it is going to do, but when you start to try things, other possibilities will offer themselves. The handle of a cup might make a nose one way up, but if you turn it round it could be a ponytail, or a handle to puppet with. A mobile phone with a cable could be the head and body of a snake one way round, or the body and head of a long-necked dinosaur the other way round. Both can work. You might change from one to the other to represent a change of character, or a change of expression.

Try holding your object in different ways.

What the audience sees.

The phone and cable as a snake.

The phone and cable as some kind of long-necked creature.

The audience fills in the gap between the object and the table top with this…

… or this. Or something else.

Be aware of the way in which the puppet exists in relation to the floor When the object comes alive, it takes on an imaginary skin and extra ‘invisible’ features, such as arms, legs, eyes, which are filled in by the imagination of the audience. For example, when the pen walks on the floor, you imagine that there are legs of some kind that it is walking on. You do this because of the gap you make between the pen and the floor where you can imagine those legs. The relationship between the object and the floor, the puppet and the puppet stage, is an essential part of the transformation of the object into a puppet.

Variations on the Exercise

• Use different materials: instead of using objects, give each person a sheet of newspaper (inspired by an exercise with Improbable Theatre). Go through the steps of the exercise in the same way, starting with flat sheets of newspaper lying on the ground in front of you, and ending up with a scrunched-up, torn, raggedy collection of fabulous newspaper beasts running about and filling the room with life.

• Use props/puppets/materials you want to explore: this exercise can empower everyone to try things in an open, non-directed way. It is a very good structured way to get to know puppets or materials for the first time.

• Pass the object to your neighbour: at STEP 2, after feeling your object with your eyes closed, pass it to the person on your right, keeping your eyes closed, and receive one from the left. Repeat the exercise and pass the object on again. Then either continue passing the objects until they have gone all the way around the circle and your first one has come back to you, or pass two or three times and then continue the exercise with someone else’s object. It is very interesting to explore objects with your eyes closed to see how they make you think and feel differently about them.

• Combine puppets to make a monster: at STEP 11, after making your individual objects walk and talk, make them meet the puppet next door to them. After meeting, make the two puppets join to make a two-part puppet. One of the objects becomes the feet and legs of the new puppet, and the other becomes the body and head. Then make the two-part puppets meet another two-part puppet, and make a four-part puppet. Keep joining the objects together until they are all involved, making a giant, multi-puppet ‘monster’.

• Name the puppets and make them talk: at STEP 11, another way to develop the end of the exercise is to name the puppets and give them a voice. Make them meet their neighbour puppets and start a dialogue. Naming the puppets makes them more real, and gives you something to refer back to later in the day.

MAKING YOUR OBJECT PERFORM

(Inspired by a class with puppeteer Steve Tiplady.)

A puppet only really comes alive when you show it to an audience. It moves in your hand, but it only really lives in the imagination of the audience. They are your co-creators and you need to involve them in your creative process. This exercise gives you a structure for presenting your object improvisation to an audience in rehearsal, and for finding out from them what you’ve got. You create a puppet stage, present your object in a miniature performance, and invite the audience to help you find its puppet character.

When you are the one who is in the audience, you watch the puppet come to life and can give feedback afterwards. Watching other people’s improvisations will inspire what you want to see the objects do, and will help you learn how to do what you want the audience to see.

The Exercise

Set up the room with the audience on one side and a stage area on the other. Everyone in the group makes up the audience, and you take it in turns to go on stage. When it is your turn to present your puppet, do it in the following way.

Set up the space with a stage and an audience.

STEP 1: When you look at the audience, they will look at you.

STEP 1: Come on stage, kneel on the ground, put your object on the floor in front of you, and look up at the audience.

STEP 2: ‘Collect’ the eyes of the audience members. Look at each of them one by one, until you have everyone’s attention.

STEP 3: When you look down at the object, you disappear and the object comes into focus.

STEP 3: Look down at your object and feel the audience follow your focus, so they are also looking at the object.

STEP 4: Take hold of the object without moving it.

STEP 4: When you can feel everyone is looking at your object, reach out and take hold of it. Make sure that you don’t move it as you take hold of it.

STEP 5: Make the object breathe.

STEP 5: Start to make the object breathe, bringing it alive.

STEP 6: Make the object wake up.

STEP 6: Make your object wake up.

STEP 7: Find its eyes and make it look around the room. Make it breathe, move, think, feel. Make it see the audience and react. Maybe it says ‘hello’.

STEP 8: Begin to develop the emotion just as you did when improvising with it in the previous exercise. Show the audience the emotional extremes and movement of the object.

STEP 9: Keep the improvisation going until you are told to stop. Usually this is 2–5 minutes.

STEP 10: Finally, listen to the audience feedback on what they saw, what they understood from what they saw, what they like, and maybe what they did not like.

Tips for Doing It Well

Hold the object the way you want the audience to see it Show them which is the front of the puppet and which is the back. They will expect you to hold it from behind.

Hold a stiff object as close to the ‘character centre’ as possible: this gives you good control and means that the audience will be able to see both the feet and the head.

Hold a floppy object at the head and the feet Holding the object with two hands will give you as much control as possible. Use your dominant hand to hold the ‘head’.

Don’t change your grip Once you have taken hold of the object, maintain the same grip. Changing the grip or passing the object from hand to hand will draw attention to you and break the focus of the audience on the puppet. Move yourself about rather than changing your grip.

Take your time: don’t be rushed Build expectation. Invest in each stage of development before moving on to the next. At the very beginning, make sure everyone is looking at you. Wait long enough for all of them to look at the puppet before you put your hand on it. Leave your hand on the puppet long enough before you start to move it. Wait for each moment to come before moving forwards. You only get one chance to do each stage and you cannot go back.

Use the audience as a ‘mirror’ While you are performing, try to understand what the audience are seeing. Listen for their reactions, for example, silence or laughter. If something you make the puppet do gets a reaction, try doing it again. Try to ‘see’ what they are seeing. Where are they seeing the puppet’s eyes? How do they see the puppet walk?

After your presentation, ask your audience specific questions: Where are the eyes? Where is the puppet looking? Are these the feet? Is it too tall or short?

Things to Notice

The object comes alive when you look at it At that moment, before you even go to take hold of it, you create a new reality. The audience sees the object in a different light: it has become a ‘puppet’. At the same time, the floor becomes the object’s stage, and you become an invisible puppeteer. This is why it is important not to move the puppet when you first take hold of it, because it is already alive in the mind of the audience, and you are reaching out to touch a living thing. If you move it when you go to take hold of it, then you become visible again, and the puppet will turn back into an object. It will die.

Hold a floppy object such as a scarf with two hands – one at the ‘head’ and one at the ‘feet’.

Move yourself around the object so that you can keep the same grip.

If you look up from your object, the audience will look at you.

Avoid doing things that draw attention to you The illusion is delicate. Anything that you do that draws attention away from the puppet, and onto you, will break the illusion. If you take a moment to adjust your leg, or break your focus, or change your grip on the object, the audience will look up at you, and stop seeing the puppet as a living being.

HOW TO GIVE FEEDBACK

Watching is as important as 'doing' in puppetry and it is always valuable to take a moment after a presentation for everyone to talk about what they have seen. Watch each other’s performances critically, paying attention to the things that make the object live, and the things that make it die. Anything that distracts you from seeing the puppet is a problem.

When giving feedback, try to be as precise as possible about what you are seeing. For example, when someone has puppeted a pen, you might say, ‘I saw a very tall thin man, with a long face on the top half of the pen, with a sort of beanie hat and a roll-neck sweater on.’ If they have used a scrunched-up piece of newspaper, you might let them know that you have seen ‘a Victorian lady in a cape and hood’, and so on.

Showing is the best way to explain what you mean by your feedback, and to learn to do it yourself. Swap places with the person, take their object, and show them what you saw in their puppet. By changing places between audience and performer you develop your ability to do what you want to see, and to see what you are doing.

‘It’s a little man, the ring in the middle of the pen is a collar and the top is a fez….’

‘It’s a Victorian lady in a cape and a hood….’

PUPPETING EMOTION

When the audience watches your object come to life they will look for what it is feeling. They will identify emotions whether you put them there or not. They will deduce what the puppet is feeling from the story they watch, and from the way you move it.

In this exercise, you let the audience guide you to develop the emotion of your object. The audience tells you what emotion they see in your puppet and you work to make it grow bigger, using movement and voice.

Sad and lonely, Mildred from Low Life (Blind Summit).

The Exercise

Set up the room so that you have an audience and a stage area. Participants will then go up one by one to do the exercise in front of the rest of the group.

STEP 1: The puppeteer places their object on the floor of the stage in front of the audience and brings it to life. They make it breathe and look around the space.

STEP 2: The audience members say what emotion they see in the object. Usually, they will agree on this. Sometimes, however, the emotion may be subtle and there will be a disagreement. In this case, they choose one and, once that choice has been made, that becomes the emotion.

STEP 3: The puppeteer then tries to make their object feel that emotion more. They make it breathe in that emotion, move with that emotion, and make the sound of that emotion. For example, if the puppet is sad, they can make it begin to cry; if it is happy, it can be made to laugh; if it is afraid, it may begin to shake; if it is excited, it might begin to pant.