22,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

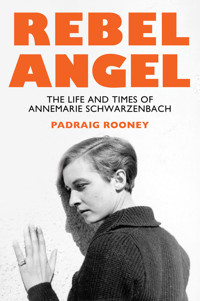

Annemarie Schwarzenbach was one of the twentieth century’s most remarkable women, possibly the greatest sexual and political radical of the 1930s. But until now she’s been largely ignored.

Born to a wealthy family in Switzerland, as a teenager she rebelled against her domineering pro-Nazi mother. She immersed herself in the antifascist, queer and artistic circles of the German diaspora of the 1930s. Her edgy glamour and androgynous beauty turned heads in the lesbian nightclubs of Weimar Berlin, on the ski slopes of St. Moritz, and in New York's luxury hotels and jazz bars.

Constantly on the move, Annemarie chronicled the low and dishonest decade leading to war through her unique journalism, writing and photography. Her work was as adventurous and uncompromising as her personal life, and reveals a deep courage, intelligence, and ambition tragically curtailed by her untimely death.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 597

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright Page

Figures

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Notes

1 Cocoon

Notes

2 Women on the Left Bank

Notes

3 Breaking the Threads

Notes

4 Closet of Selves

Notes

5 Pilgrim Soul

Notes

6 Lavender Marriages

Notes

7 Two Women, a Ford and a Rolleiflex

Notes

8 Enemies of Promise

Notes

9 Running on Empty

Notes

10 Heart of Darkness

Notes

Afterword

Bibliography

Index

End User License Agreement

List of Illustrations

Chapter 1

Robert-Ulrich (Robuli), Suzanne, Annemarie, Alfred (Pedy) and baby Hans (Hasi) S...

Annemarie in her much-loved lederhosen, July 1918. Photo by Renée Schwarz...

Emmy Krüger in Rheinfelden, July 1916. Photo by Renée Schwarzenbac...

Annemarie, age 16, serving at a hunting party, October 1924. Photo by René...

Annemarie during spring break from school, 1926. Photo by Renée Schwarzen...

Annemarie with Pastor Ernst Merz during her time in the Wandervogel, 1925. Photo...

Fetan classmate Mady Hosenfeldt and Annemarie, August 1926. Photo by René...

Mother and daughter, [1930?]. Photo by Renée Schwarzenbach-Wille

Gundalena Wille, Annemarie, Renée, Suzanne, Hasi and Pedy, 7 July 1921. P...

Chapter 2

Annemarie picnicking in the Foret de Chantilly with Dominique Schlumberger, 1929

Annemarie with Hélène d’Oliveira, 1927

Chapter 3

Claude Bourdet

Ruth Landshoff and Annemarie, photographed by Karl Vollmoeller, Palazzo Vendrami...

Erika and Klaus Mann, 1927. Photo by Edward Wasou

Thea Frenssen and Annemarie, Bocken 1932

Annemarie before driving to Berlin, 19 September 1931. Photo by Renée Sch...

Chapter 4

Erika Mann, Annemarie, Klaus Mann, Venice 1932

Inge Westendarp, Margot Lind and Lisa von Cramm, 1936. Photo by Annemarie Schwar...

Chapter 5

Klaus Mann. Photo by Annemarie Schwarzenbach

Children in Turkey, 1933–34. Photo by Annemarie Schwarzenbach

A horse-drawn tram in Iraq. Photo by Annemarie Schwarzenbach

Chapter 6

Claude Clarac in Farmanieh, Persia, summer of 1935. Photo by Annemarie Schwarzen...

Annemarie en route to marriage, Trieste 17 April 1935. Photo by Renée Sch...

Annemarie in Trieste before boarding the boat to Beirut, 1935. Photo by René...

Annemarie Schwarzenbach in Persia, 1935. Photo likely by Barbara Hamilton-Wright

Jalé (rear, third left) and her siblings at the Turkish Embassy in Tehran...

Barbara Hamilton Wright, Annemarie, Claude Clarac, at the Scharis-Danek hunting ...

Erika Mann, W.H. Auden by Alec Bangham, 1935

Chapter 7

Annemarie Schwarzenbach with her Rolleiflex Standard 621 camera, 1938. Photo by ...

Barbara Hamilton-Wright, 1936–38. Photo by Annemarie Schwarzenbach

Road labourers in Montgomery, Alabama. Photo by Annemarie Schwarzenbach

Children in Charleston, South Carolina. Photo by Annemarie Schwarzenbach

Chapter 8

Alfred Schwarzenbach in the train at Arosa, 1936. Photo by Renée Schwarze...

Erika Mann in Sils, 1936. Photo by Annemarie Schwarzenbach

Ella Maillart packing the car, British Consulate, Meshed, Iran, 1939. Photo by A...

The standing Buddhas in Bamiyan, Afghanistan. Photo by Annemarie Schwarzenbach

A seated boy in Mandu, India. Photo by Annemarie Schwarzenbach

Chapter 9

Carson McCullers, c. 1940

Annemarie at Dubendorf Airfield, September 1939

Chapter 10

Annemarie and Madame Orlandi, wife of the Swiss Consul, and dog Folette, Thysvil...

Annemarie in her pith helmet on the Jturi (Aruwimi) river. Photographer unknown

Madame Hedwig Vivien, Belgian Congo. Photo by Annemarie Schwarzenbach

Claude Clarac, Rabat, Morocco. Photo by Annemarie Schwarzenbach

Annemarie Schwarzenbach on her deathbed, Sils Baselgia, 15 November 1942. Photo ...

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Pages

iii

iv

vi

vii

viii

ix

x

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

313

314

315

316

317

318

319

320

321

322

323

324

325

326

327

328

329

330

331

332

333

Rebel Angel

The Life and Times of Annemarie Schwarzenbach

Padraig Rooney

polity

Copyright Page

Copyright © Padraig Rooney 2025

The right of Padraig Rooney to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2025 by Polity Press

Epigraph to Chapter 4 reproduced with the generous permission of the Truman Capote Literary Trust.

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

111 River Street

Hoboken, NJ 07030, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-6629-7

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2024940082

by Fakenham Prepress Solutions, Fakenham, Norfolk NR21 8NL

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

Figures

Robert-Ulrich (Robuli), Suzanne, Annemarie, Alfred (Pedy) and baby Hans (Hasi) Schwarzenbach, 16 August 1915. Photo by Renée Schwarzenbach-Wille.

Annemarie in her much-loved lederhosen, July 1918. Photo by Renée Schwarzenbach-Wille.

Emmy Krüger in Rheinfelden, July 1916. Photo by Renée Schwarzenbach-Wille.

Annemarie, age 16, serving at a hunting party, October 1924. Photo by Renée Schwarzenbach-Wille.

Annemarie during spring break from school, 1926. Photo by Renée Schwarzenbach-Wille.

Annemarie with Pastor Ernst Merz during her time in the Wandervogel, 1925. Photo by Renée Schwarzenbach-Wille.

Fetan classmate Mady Hosenfeldt and Annemarie, August 1926. Photo by Renée Schwarzenbach-Wille.

Mother and daughter, [1930?]. Photo by Renée Schwarzenbach-Wille.

Gundalena Wille, Annemarie, Renée, Suzanne, Hasi and Pedy, 7 July 1921. Photo by Renée Schwarzenbach-Wille.

Annemarie picnicking in the Foret de Chantilly with Dominique Schlumberger, 1929.

Annemarie with Hélène d’Oliveira, 1927.

Claude Bourdet.

Ruth Landshoff and Annemarie, photographed by Karl Vollmoeller, Palazzo Vendramin, Venice, September 1930.

Erika and Klaus Mann, 1927. Photo by Edward Wasou.

Thea Frenssen and Annemarie, Bocken 1932.

Annemarie before driving to Berlin, 19 September 1931. Photo: Renée Schwarzenbach-Wille.

Erika Mann, Annemarie, Klaus Mann, Venice 1932.

Inge Westendarp, Margot Lind and Lisa von Cramm, 1936. Photo by Annemarie Schwarzenbach.

Klaus Mann. Photo by Annemarie Schwarzenbach.

Children in Turkey, 1933–34. Photo by Annemarie Schwarzenbach.

A horse-drawn tram in Iraq. Photo by Annemarie Schwarzenbach.

Claude Clarac in Farmanieh, Persia, summer of 1935. Photo by Annemarie Schwarzenbach.

Annemarie en route to marriage in Beirut, Trieste 17 April 1935. Photo by Renée Schwarzenbach-Wille.

Annemarie in Trieste before boarding the boat to Beirut, 1935. Photo by Renée Schwarzenbach-Wille.

Annemarie Schwarzenbach in Persia, 1935. Photo likely by Barbara Hamilton-Wright.

Jalé and her siblings at the Turkish Embassy in Tehran. Photo by Annemarie Schwarzenbach.

Barbara Hamilton Wright, Annemarie, Claude Clarac, at the Scharis-Danek hunting camp, Persia, 1935.

Erika Mann, W.H. Auden by Alec Bangham. Modern bromide print from original negative, 1935.

Annemarie Schwarzenbach with her Rolleiflex Standard 621 camera, 1938. Photo by Anita Forrer.

Barbara Hamilton-Wright, 1936–38. Photo by Annemarie Schwarzenbach.

Road labourers in Montgomery, Alabama. Photo by Annemarie Schwarzenbach.

Children in Charleston, South Carolina. Photo by Annemarie Schwarzenbach.

Alfred Schwarzenbach in the train at Arosa, 1936. Photo by Renée Schwarzenbach-Wille.

Erika Mann in Sils, 1936. Photo by Annemarie Schwarzenbach.

Ella Maillart packing the car, British Consulate, Meshed, Iran, 1939. Photo by Annemarie Schwarzenbach.

The standing Buddhas in Bamiyan, Afghanistan. Photo by Annemarie Schwarzenbach.

A seated boy in Mandu, India. Photo by Annemarie Schwarzenbach.

Carson McCullers, c. 1940.

Annemarie at Dubendorf Airfield, September 1939.

Annemarie Schwarzenbach and Madame Orlandi, wife of the Swiss Consul, and dog Folette, Thysville, Belgian Congo, 1942.

Annemarie in her pith helmet on the Jturi (Aruwimi) river. Photographer unknown.

Madame Hedwig Vivien, Belgian Congo. Photo by Annemarie Schwarzenbach.

Claude Clarac reading in bed; Rabat, Morocco. Photo by Annemarie Schwarzenbach.

Annemarie Schwarzenbach on her deathbed, Sils Baselgia, 15 November 1942. Photo by Renée Schwarzenbach-Wille.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to the following for invaluable help with research: Stephanie Cudre-Mauroux, Christa Baumberger, Rudolf Probst, Sabrina Friederich, Kristel Roder at the Swiss Literary Archives in Bern; Thomas Bruggmann and Alexis Schwarzenbach at Zentralbibliothek Zurich; Dinah Berner at Monacensia im Hildebrandhaus-Literaturarchiv in Munich; Heidrun Fink at the Deutsches Literaturarchiv Marbach, Marbach am Neckar; archivists and librarians at Basel University Library for access to the Otto Kleiber and Carl Burchardt papers; Martin Waldmeier at Zentrum Paul Klee in Bern for his knowledge of Schwarzenbach’s photographs; Maren Richter, document curator at Obersalzberg, for agreeing to talk to me about Maria Daelen; Patrick Moser at Historisches Museum Basel for his knowledge of Switzerland during wartime; Carole Bonstein Archive, Geneva.

Alexander Rankin and Laura Russo welcomed me at the Howard Gottlieb Archival Research Center, Boston University; archivists at Washington University in St. Louis for the Robert Newton Linscott papers; archivists at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin for permission to consult the Carson McCullers papers.

Many people provided assistance in the writing of this book. Roger Perret, scholar and editor of Schwarzenbach’s work, shared valuable documents. Schwarzenbach’s biographer and editor in French, Dominique Laure Miermont-Grente, took time to answer my questions. Thomas Blubacher on a sunny day in Rheinfelden fleshed out the career of Ruth Landshoff-Yorck. Carlos Dews kindly read my manuscript with his expert eye for Carson McCullers. Sarah Schulman also read the manuscript and provided a much-needed boost. Aine Keenan brought to bear her enthusiasm and considerable knowledge of Ella Maillart. Todd D. Smith, Executive Director of the Bechtler Museum of Modern Art in Charlotte, NC, commissioned voiceovers of my Schwarzenbach translations. Brian Ferrari shared his knowledge of cabaret singer Spivy le Voe, not to be confused with Victoria Spivey. Elsa Fischer in Bern and Hilary Cole in Basel sent clippings from Swiss newspapers. Kirsten Jaehde helped with German translation. To all of them, many thanks.

Introduction

In 2018 the New York Times published an obituary of Annemarie Schwarzenbach some seventy-five years after her untimely death. The Swiss author’s stock was up and a desire to correct the dead-white-male bias of historical reporting led the obituarist to wonder what lay behind this resurgence of interest: gay cult figure, androgynous glamour, the romance of trustafarian travel, drugs and an early death?

All of the above. Schwarzenbach was ‘a beautiful but troubled soul’, as the Times obituary put it, well aware of the effect she had on men and women. There lies the crux, between physical beauty and trouble of soul. She struck Nobel laureate Thomas Mann as an ‘extraordinarily pretty’ boy. Several years later, by which time morphine had made its mark, he called her ‘a ravaged angel’. Another Nobel laureate, Roger Martin du Gard, referred to her ‘inconsolable angelface’. A stable of Weimar writers worked her androgynous effect into their fictional characters. Women and men stood in awe of her beauty, on the ski slope, in cafés and nightclubs. This youthful otherworldly effect – spoiled innocence, fallen angel – hasn’t gone out of fashion and exerts a similar pull on a modern audience. Those whom the gods love die young. Schwarzenbach died in her own bed during a war when millions less fortunate suffered horrific deaths, when her friends found themselves scattered to the winds of exile, barely escaping with their lives. Her life played out against the rise of the Nazis and the German diaspora in France and New York. Between one war and another, Schwarzenbach burned brightly, as we like to gloss such tragic romantics, in ‘a world of cocktails and cigarettes, sleepers and sleek limousines’, as critic Carl Seelig eulogized her. She reported in journalism and fiction on the disorder of the decade, the rise of fascism and the allure of travel. Being Swiss cushioned her movements, as did wealth, looks and a diplomatic marriage. Cursed by restlessness, the arc of her short life nonetheless did not bend towards fulfilment. Quite the contrary: drugs, schizophrenic episodes, and an inability to be still all fractured her sense of self and eventually her writing.

The twenty-first-century mode latches onto rebels like Schwarzenbach as precursors to our own identity politics. Her illness, addictions and lesbianism get reconfigured as symptoms of social and parental oppression: she becomes a victim in the ‘live fast, die young’ club. This remaking was already nascent in the generation after the First World War, cropping their hair, shooting up and tuning out in the dives of Berlin and Montparnasse, blaming their elders for the tribulations of the Great War. Schwarzenbach’s glamour-girl image, her queerness, sometimes obscures her role as a political rebel against the rise of fascism. This entanglement of meme and content, image and politics, photography and writing, is central to her life. Interest in her writing and photos is inextricable from her visual appeal, as her earlier biographer, Charles Linsmayer, pointed out. Schwarzenbach’s cult, her short, glamorous, tragic life, her pretty face, have all tended to upstage the writing.1 This biography attempts to redress that balance.

The face undoubtedly helped. Schwarzenbach was memorably photographed, in particular by Marianne Breslauer, whose portrait of ‘the writer Annemarie Schwarzenbach’ appeared in the October 1933 edition of Berlin’s Uhu magazine and over the following century has come to shape an aesthetic, an infinitely marketable lesbian look, noli me tangere, disaffected cool. Schwarzenbach in turn wielded her Rolleiflex throughout her travels and many of these photographs were published in magazines in her lifetime. The visual record foregrounds her cars, the steamships, exotic wastelands, bedraggled refugees and young fascists of the thirties; Persia, Afghanistan, Russia, the underbelly of the United States: trouble spots still in the headlines. She joins the sorority of female explorers of the Middle East, breaking the bounds of gender while not straying too far from the colonial hotel and the diplomatic bag. Constantly writing, observing and responding to her tarnished times with great intelligence, style and political engagement, she managed to fall on the right side of history despite her Nazi-sympathizing family. For a decade between the wars, she seemed to be at the centre of the zeitgeist, to try hard to overcome her addiction and her psychological frailty. She was more than just a pretty face.2

*

At the start of the coronavirus pandemic in March 2020, just before countries closed their borders and went into lockdown, I was skim-reading three decades of diaries in the Monacensia Library in Munich, where the Mann family archives are preserved. Thomas Mann’s children, Erika and Klaus, both gay, had been close friends of Annemarie all her adult life and she was welcomed at the family dinner table. The diaries belonged to opera singer Emmy Krüger, Renée Schwarzenbach’s friend – girlfriend, lover, lady’s companion? Krüger transcribed her diaries in pencil, for the most part, onto tiny three inch by two inch pages folded between the original diary covers in a cramped, evenly flowing hand, using up all the available space. They were difficult to make out in German. I was wearing white gloves and wielding a magnifying glass, Google translate open on the laptop beside me, with a view out the window onto the linden trees fronting the Isar river and the Englischer Garten. The evenness of the hand, the sameness of the writing instrument and the detached pages, slipped between card and leatherette covers year after year, gave the transcription away – copied out some time after the war. I was anticipating the annus miserabilis 1933, when Krüger sang at Hitler’s behest in Munich. But the 1933 diary was missing. When I pointed this out, the archivist shrugged her shoulders as though she’d encountered such lacunae before. Diaries are like families: working up their best stories, trimming the embarrassments, putting on a brave, made-up face to the world in different layers of reality: fact, myth, history, fiction, lie. Krüger’s diaries and their elisions illustrate the difficulty of seeing clearly the progress of National Socialism in the twenties and thirties long after the apotheosis of the movement and its defeat.

The politics of memory proceeds by selective amnesia, and homosexual memory in families, more often than not, takes the same primrose path. Tampering with the written record occurred on the afternoon of Annemarie’s death when Renée burned her daughter’s diaries and correspondence, including letters from Erika and Klaus Mann, Erich Maria Remarque, Carson McCullers, her husband Claude Clarac as well as countless girlfriends and confidants. This too was an attempt to set the record straight, not just about Annemarie but also her fraught relationship with her mother. After the war, when traveller Ella Maillart wished to publish her account of a journey with Annemarie to Kabul, The Cruel Way, Renée insisted on disguising her daughter’s name and on editorial oversight. Throughout history, family and inheritance law has sidelined homosexual relationships in the name of propriety – and property – while the written record has been winnowed, sanitized if not outright gone up in flames. The Nazis were past masters at this too.

Schwarzenbach took an early definitive stance against National Socialism. In Munich I’d arranged to meet Dr. Maren Richter, historian and curator at the Obersalzberg Memorial and Educational Center at Berchtesgaden, Hitler’s mountain fastness. We discussed German resistance, in particular Annemarie’s friends Maria Daelen, Albrecht Haushofer and others in the context of Operation Valkyrie, the failed assassination of the Führer in 1944. Daelen had a long affair with Wilhelm Furtwängler, chief conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic, whose own career and allegiance remain contested. Schwarzenbach’s resistance was not simply a matter of good and bad Germans but of coming to terms with the complexity of responses to National Socialism as it evolved over twenty years among family and friends. Hitler’s promise to make Germany great again appealed to all sorts of people but not to socialists, communists, the writers and artists of Weimar’s cultural renaissance, many of whom were Jewish and gay in both senses of the word. This was Annemarie’s tribe and she ran with it early. Her friend and fellow exile Klaus Mann describes her as ‘one of these peculiar sham-émigrés’,3 but her political stance was extraordinarily brave and unwavering in the face of her staunch family, their early fundraising on Hitler’s behalf, and their militaristic bent.

*

Schwarzenbach first attracted attention in Switzerland with the publication in Zurich of her novel Friends of Bernhard (1931) when she was twenty-three. Her second book, Lyric Novella (1933), its Berlin publication overshadowed by Hitler’s accession to power, employs the device of transmuting lesbian experience into heterosexual narration: changing the pronouns. A third novel, set in an Austrian ski resort, Flucht nach oben, resurfaced after her death and was published in 1999. A collection of short stories, Bei diesem Regen, and a biography of a mountaineer, Lorenz Saladin: Ein Leben für die Berge, garnered some attention during her lifetime.

A combination of politics, family disapproval, restlessness and sheer gumption led to Schwarzenbach’s decade of travel through the Middle East, Persia, Afghanistan, the Soviet Union, the Baltic states, three times to the United States and a final trip to the Belgian Congo during the war. Pace Disraeli, for her the East became a career: she got three or four books out of it, a useful husband, thousands of photos and a sense of self, her own private Araby. ‘She was restless and her quest for happiness had given way to a quest for tranquillity’, writes her friend Ruth Landshoff-Yorck. Throughout her travels she wrote for Swiss newspapers and magazines (German outlets being denied her) on topics ranging from modernization in Ankara, archaeological digs, female education in Persia, the first Soviet Writers Conference in Moscow, to politics in the Balkan States, race and labour issues in the Rust Belt and the American South, development in the French Congo. In the United States her journalism became more hard-hitting, radical, observant – her editor, Otto Kleiber at Basel’s National-Zeitung, thought it unsuitable for the ‘women’s pages’. Her tendency was to see the bread-and-butter writing she did as exactly that, filling the gaps between inspiration. She wrote quickly, with little revision, in a mode that became increasingly self-involved. While her youthful talent as a fiction writer might have been realized had she lived, journalism, travel, addiction and mental instability were her enemies of promise. By the time of her death, nonetheless, Schwarzenbach had a body of work and a reputation in Switzerland as a brave, intrepid, idiosyncratic writer, albeit one you might not want your daughter to meet or emulate, a reputation that has only grown in the eighty years since.

This first account in English of Schwarzenbach’s life and times has taken me to the edge of my linguistic abilities, encompassing research in German and French in Basel, Bern, Boston, Lausanne, Marbach, Munich and Zurich, much of it undertaken during half-terms, in the intervals of lockdowns or between six and eight in the morning, before homeroom kicked in. Rebel Angel has benefited from earlier biographies by Areti Georgiadou, Dominique Laure Miermont, Charles Linsmayer and Alexis Schwarzenbach, and from the pioneering editing and research of Roger Perret, Walter Fähnders and Dominique Laure Miermont, among others. Three Schwarzenbach titles have been translated into English by Lucy Renner Jones and Isabel Fargo Cole, published by Seagull Books. Citations from Schwarzenbach’s original German manuscripts in the Swiss Literary Archives, from the Schwarzenbach family archives in Zentralbibliothek Zurich and from her work published by Lenos Verlag are my English translations alone.

Notes

1

Charles Linsmayer,

Annemarie Schwarzenbach: Ein Kapitel tragische Schweizer Literaturgeschichte

, pp. 198–202.

2

Alicia P.q. Wittmeyer, ‘Overlooked No More: Annemarie Schwarzenbach, Author, Photographer and “Ravaged Angel”’,

New York Times

, 10 October 2018.

3

Klaus Mann,

The Turning Point

, p. 278.

1Cocoon

Moreover, he is a prey to numerous maladies … and the fibre of his cocoon reflects such disorders.1

Frank R. Mason, The American Silk Industry and the Tariff

Cantilevered over the cash machines at the junction of 32nd Street and Park Avenue in New York is a distinctive bronze clock. On the hour, the figure of Zarathustra waves a wand and a slave swings a hammer against the cocoon at his feet, from which emerges the Queen of Silk bearing a tulip. This elaborate timepiece, ornamented with mulberry leaves, represents the mythical origin of silk in Persia, as well as being a nod to Swiss timekeeping. 470 Park Avenue is still called the Schwarzenbach Buildings, commemorating the family that brought the silk business to America.

In Switzerland, sericulture owes its exploitation to the Huguenots, many of whom were weavers fleeing French oppression. Along the shores of Lake Zurich, the cottage industry expanded with mechanization during the nineteenth century – black taffeta, derived from the Persian word for ‘twisted’ or ‘woven’, became the Zurich speciality. Factories sprang up outside the lake villages of Adliswil and Horgen, and silk was exported all over Europe and to the growing American market. By the end of the nineteenth century, Zurich boasted the second-largest silk production in the world, rivalled only by Japan.

Schwarzenbachs are attested around the lake at least since the fifteenth century. Founded in 1828, the Schwarzenbach silk firm was based in Thalwil, about twelve kilometres south of Zurich. Johannes Schwarzenbach had intended that his elder son August should take over the business and the younger son Robert was destined for a plantation career in Java, then a Dutch colony. The Java project fell through and in 1859 Robert was dispatched to New York where he established a branch of the family business. The American Civil War brought tariffs – imports of raw silk to the United States quadrupled between 1860 and 1870, and fortunes were made. Johannes died suddenly of congenital heart failure, Robert Schwarzenbach returned to Zurich, and together with August they transformed the family firm into one of the great industrial fortunes of the nineteenth century with branches in London, Paris, Lyon, Berlin, Milan and New York. Berlin’s Volkszeitung dubbed Robert the ‘silk king of the world’. He built an imposing mock-Elizabethan residence facing the lake at Rüschlikon to match – it had one of the first tennis courts in Switzerland.

At the firm’s height, it employed 28,000 workers, providing a local library and teetotal restaurant, a raft of improving evening classes along the lines of the Women’s Institute in Britain. Following the Franco-Prussian war of 1871, Alsace was incorporated into the German Empire under Bismarck. The Germans encouraged Swiss investment and a Schwarzenbach factory opened at Huningue right on the border with Basel, taking advantage of cheaper labour and lower tariffs. That inveterate wanderer D.H. Lawrence left his native England in 1912 and, travelling south along the shore of the lake at Zurich, noted the immigrant labour: ‘they were all workers in the factory – silk, I think it was – in the village. They were a whole colony of Italians, thirty or more families.’2

In 1904, Robert Schwarzenbach died, like his father, of heart trouble, and the business passed to the sons. Alfred was the first member of this industrialist family to pursue further education, studying law in Berlin and Leipzig and graduating magna cum laude. Alfred’s repertoire as a gentleman of the industrial elite included hunting in Baden, Pears Soap, London tailors and stays at Claridge’s. He was characterized by mildness and an ability to conciliate in his often tempestuous family. After a short period in a Paris bank, he returned to oversee the family firm. The greater part of its wealth stemmed from the expanding American market, where labour was cheap and profits continued to climb. Erected in 1912, the Schwarzenbach Buildings on Park Avenue testify today to this solidity and opulence. By 1928 there were 4,445 Schwarzenbach looms in the United States and a total of 3,977 in Switzerland, Germany, France and Italy combined.3 With the Wall Street Crash the price of silk fell over the following years and so 1928 can be considered the apogee of this most successful family business.

On her mother’s side, Annemarie Schwarzenbach descended from military stock. Her grandmother, Clara Wille, who survived her by three years, was the daughter of Friedrich Wilhelm Graf von Bismarck, a young cavalry officer ennobled for his part in Napoleon’s Russian campaign. Bismarck’s second marriage to a woman forty-one years his junior produced two children: August and the long-lived Clara, born in 1851. Following an idyllic childhood on the shores of Lake Constance, August joined a Baden regiment but sided with the Prussians in the wars of 1870 when Germany became united under a third cousin, Otto von Bismarck. Annemarie Schwarzenbach’s mother was not inclined to underestimate this swashbuckling aristocratic heritage.

Clara, for her part, first spotted Ulrich Wille in Rome in the winter of 1868. They took to the floor at Berlin’s society balls and were engaged to be married. It was a glittering world of dancing, social calls and garrison life, all in the middle of a conflict that would unify Germany, bring on two world wars and redraw the map of Europe over the coming century. Ulrich Wille hailed from a literary and political family with origins in La Sagne, a village in the canton of Neuchâtel close to the present border with France. The family name had been the more French Vuille, and the change to Wille as well as Ulrich’s birth in Hamburg in 1848 indicate political affiliations. His father, François, a liberal journalist, had fled Frankfurt following the failed 1848 revolution, a swathe of revolts across European states attempting to free themselves from aristocratic autocracy. François was a forty-eighter in exile in Switzerland, based on the shore of Zurich’s lake at Mariafeld, where he and his wife Eliza, from a Hamburg shipping family, hosted a literary salon. Gottfried Keller, Arnold Böcklin, Franz Liszt and Richard Wagner were some of the luminaries hosted by the Willes. Their son Ulrich inherited the chip on the shoulder that comes with political exile, the stubbornness of the revolutionary and an appreciation for pan-European culture that he would hand on to his grand-daughter. Despite his cultivated upbringing, Ulrich was a child of the garrison, German unification and imperial might. Like Clara, he had somewhat tenuous connections to the Swiss Federation into which neither of them had been born.

Annemarie Schwarzenbach’s mother, Renée, born in 1883, was the youngest in a family of three boys and a girl. Renée enjoyed sledding on the Dolder, picnicking on the shores of the lake with like-minded debutantes and their young pretenders. Her father climbed the ranks of the military, from division commander to colonel on the eve of the First World War. He dabbled in municipal and state politics and developed a reputation for siding with Prussian militarism to the chagrin of Switzerland’s French-speaking confederates. Renée’s brothers made good marriages; the Wille-von Bismarcks could count on military cachet but were neither of old Zurich stock nor particularly rich. The two daughters – Renée and Isi – could expect to marry well by virtue of name and standing.4

It was a horsey childhood as befits a military family at the end of the age of cavalry, when Sisi of Austria proudly saddled up and the Transvaal was part of the holdings of empire. Just as her daughter Annemarie would be among the first generation of motoring women to take to the road, so Renée’s overriding passion all her life was for horses, emblematic of her father’s rank as head of cavalry and of her nineteenth-century aristocratic entitlement. Her uncle August von Bismarck had a large house and stables at Freiburg, abutting the Black Forest, where Renée liked to ride. She rode astride: no side-saddle for her.5 Her youngest son, Hasi, went on to win a silver medal for horse riding in the 1960 Rome Olympics. Renée liked to take the reins and all biographical accounts agree on her formidable character, almost a caricature of German military rectitude: hierarchy, discipline, horsemanship. This assertive streak derived from her father but also from the habits of dressage.

Her three older brothers brought their friends to the house and the teenage Renée’s emotional weather ran to stormy. If the boys were horsey, all the better. At age fourteen she fixed up a darkroom under the eaves at Mariafeld and began to develop her own photographs, snapping horses and people with equal passion. She attended the Villa Yalta girls school in Zurich. Though never much bothered by academics, she took to tennis and violin practice, Tannhäuser and drama, especially enjoying male roles. In some off-stage photos she smokes a pipe. Her affections were showered on young men and girls alike. Bursts of feeling confided to her diaries and snapped in the photographic record stem from unbridled pash, romantic fantasy and a delight in imbroglio for its own sake.6 Around 1900 the sixteen-year-old Renée moved on from ecstatic outpourings about Lily Fierz to the twenty-one-year-old Inez Rieter, while simultaneously swooning over Richard Vogel, a lieutenant pushing thirty. All her life, Renée was able to divide her romantic attention between men and women.

Her parents sent her to the Villa Béatrix finishing school in Geneva to tame her character, a move she would employ with her own recalcitrant daughter when the time came. Boarding school brought out Renée’s head girl propensities and succeeded in sharpening her penchant for special friendships – ‘Ich schwärme fur Sie!’ (‘I’ve got a crush on you!’) was the refrain of her girl-filled diaries. She liked to project herself as rebellious and daring – in manner if not in politics and economics. Conventionally unconventional, she rarely strayed from the strictures of her upbringing and class. Her biographer and grand-nephew, Alexis Schwarzenbach, teases out the particular quality of her love for women too easily subsumed under what used to be thought of as ‘going through a phase’. Renée’s long phase carried over into an accommodating marriage, running parallel to a thirty-year relationship with the diva Emmy Krüger.

Although Renée’s first sexual experience occurred at boarding school, it would be wrong to dismiss her love for Claire Thon as merely a ‘special friendship’. … Hand in hand, however, went the conviction that the acme of personal happiness belonged in traditional marriage.7

On her last night at boarding school, all three roommates’ beds were joined together and there was champagne, and over the rest we draw a veil.

It was a class and time when education didn’t much get in the way of picnics on the lake island of Lützelau or a tumble on the Dolder snow, either of which might lead to a marriage proposal. Parents kept a wary eye, estimating monetary worth and emotional valence. Renée met Alfred Schwarzenbach in the course of a courtesy call she made to the family home at Rüschlikon across the lake in the summer of 1903. She’d had her eye on him since February and Alfred’s youngest sister Olga might have acted as intermediary. They belonged to a similar social set, though the Schwarzenbachs were immensely richer than the Willes. Renée returned home across the lake in the Schwarzenbach motorboat and the two families eventually gave their imprimatur to an engagement.

Alfred and Renée were married in Meilen on 11 February 1904. The lake was stormy and it rained but cleared for the wedding breakfast at Mariafeld. The happy couple departed on a seven-week honeymoon beginning in the Bellevue Hotel in Bern, where they returned on occasion over the years for anniversaries to the same bridal suite high above the Aar River. For the first nine years of their marriage, they occupied an elegant villa with garden and stables on Parkring in Zurich-Enge, next door to Alfred’s Aunt Mathilde in the Villa Ulmberg. Their first son, Robert, or Robuli as he was known, was born at midnight on 15 December 1904 and a second child, Suzanne, in 1906. When Robuli was a year old, his mother worried about his lack of progress in speech. Speech never really developed and doctors speculated over the years as to the probable cause; there appeared to be no problem with hearing or vocal cords. Autism, in hindsight, seems likely, although at the beginning of the last century the condition was little known and tended to be misdiagnosed as idiocy or hydrocephalus. The Zurich psychiatrist Carl Jung was to hand at the Burghölzli Clinic. By age six, her first child showed little if any development of speech and was cared for henceforth in a clinic for handicapped children in southern Germany, with visits home to Bocken. Robuli required specialist treatment and care for the rest of his life.

By 23 May 1908, when Mina Renée Annemarie Schwarzenbach was born, the parents might have been hoping for a second son. It was a sultry Saturday turning to snow overnight, obscuring the mountains at the end of the lake. A difficult birth, a nine-pound child. A fourth child in 1911 – Alfred (Freddy) and a fifth two years later in 1913 – also a boy, Hans (Hasi) – assured the patriarchal line. At the time of Freddy’s birth, the six-and-a-half-year-old Robuli still showed little sign of communicating normally – and so on Freddy’s shoulders rested the family inheritance and his father’s name.

*

Hilary Mantel, discussing Princess Diana, a fourth girl in a family wanting a male heir, posits the theory that ‘unwanted or superfluous children have difficulty in becoming embodied; they remain airy, available to fate, as if no one has signed them out of the soul store’.8 While Renée was a loving mother, very present in the lives of her five wanted children, her attention could be uneven as Mantel suggests can be the case in sprawling aristocratic families. Renée herself had wanted to be a boy when she was a child. Robuli’s difficulties preoccupied her to the detriment of her relationship with her second child Suzanne, who got on better with her father. With the birth of Annemarie, the mother’s favouritism became evident. Annemarie took to horse riding and rode all her life; Suzanne did not. ‘Annemarie always won people over, as I stood by. Unnoticed’, Suzanne recalled.9 Mantel’s phrase ‘difficulty becoming embodied’ describes Annemarie’s lifelong sense of herself as occupying a female carapace or grappling with a split between body and soul, a split to which we might now put a different name.

Robert-Ulrich (Robuli), Suzanne, Annemarie, Alfred (Pedy) and baby Hans (Hasi) Schwarzenbach, 16 August 1915. Photo by Renée Schwarzenbach-Wille

Courtesy of Zentralbibliothek Zürich

As a society lady with decided musical tastes, Renée frequented the company of female artistes – singers, actresses – to a degree that would have caused scandal to a married man. In 1910, two years after Annemarie’s birth, she encountered Emmy Krüger, a twenty-four-year-old opera singer from Frankfurt, performing for the first time at the Stadttheater in Zurich. Renée was twenty-seven, a mother of three (soon to be four). She embarked on a relationship with the singer which endured for over three decades.

Renée clearly championed Emmy’s singing career, followed her from performance to performance, and sought to influence casting decisions where she could. She liked to take control and to get her way. Her strong-willed character made her compelling as a society hostess and dovetails into her attraction to right-wing politics. ‘Renée arrived – what a miracle to experience such friendship?’10 Krüger’s diary records time and again. Krüger was career-minded, given to enthusiasms, slights and exclamation marks, somewhat preening and kitsch, like the opera world itself. As the children grew, she took a vicarious delight in their doings. As Renée’s relationship with her deepened, the singer had her own room in the Schwarzenbach home and was invited to family events. Krüger’s widowed mother at times visited Bocken for prolonged periods; her ashes rested there in the extensive gardens. Renée shuttled between Zurich and Munich for musical events and Emmy became the live-in diva that the children came to know as mama’s friend, later referred to by Annemarie as ‘die Dame Krüger’. Alfred, for his part, displayed ‘a baffling tolerance towards his wife’s love affairs with other women, clearly setting him apart from other bourgeois family men of the time’.11 It was an unusual ménage, papered over with propriety, extraordinary for the time and place.

Renée seems to have been aware of Annemarie’s boyish or tomboyish tendencies from an early age, and to have played with them. The photographic record shows Annemarie as child and adolescent adopting at Renée’s instigation a number of masculine alter-egos: Knaben Fritz, der Rosenkavalier or an accordion-playing sailor. Just as she named her horses after Wagner figures, Renée enjoyed photographing her daughter in theatrical costumes drawn from opera and dressing her children up for special occasions. For the golden wedding anniversary of Ulrich and Clara Wille at Mariafeld, Annemarie was got up as Richard Wagner, the favourite composer of her mother and her mother’s friend. This transvestite tendency, though occasional, nonetheless reveals Renée’s opera-buff and sublimated lesbian character. She understood the theatricality of costume expressing different selves through role play, an understanding she passed on to her always savvily-dressed daughter:

Annemarie in her much-loved lederhosen, July 1918. Photo by Renée Schwarzenbach-Wille

Courtesy of Zentralbibliothek Zürich

Annemarie’s dressing up in boy’s or male clothes was confined to special occasions, while her day-to-day attire was similar to that of girls her age. Her hair, however, she kept cut short, and already by age seventeen she sported the side-parted Eton crop which characterized her perfectly androgynous look as an adult.12

As an adult undergoing treatment for addiction, Annemarie remembered the airless atmosphere of her mother’s love:

She spoils me with her love. She brought me up as a boy, and like a child prodigy. She knows all my feelings like her own, those she has never followed through on. But she has misinterpreted me ever since I was thirteen, and no longer her pageboy.13

In an early text, Annemarie describes her awareness of older women in a memory from childhood suffused with feverishness and desire:

Attractive women used to visit our house long ago when I was very young. They sat with mother and drank tea from blue china cups. When I presented myself, they held me close and caressed me. And their pale hands gave off a scent, tender and sweet, that lingered long after in the nursery. I sat still and breathed it in. … But I felt that something was wrong, and cried to myself. Whenever I encountered beautiful women, injustice, the sense of wrong, returned.14

In October 1912 the family moved to Bocken along the lakeshore in Horgen, to a large baroque house built in 1688, with extensive parkland, stables and dependencies. From the topmost floor it had a view south across the lake to the Alps. To the east, it overlooked Meilen and the Wille home at Mariafeld. To the north Zurich city. Alfred and Renée turned Bocken into a family home of extraordinary splendour, epitomizing the wealth and culture of the nineteenth-century industrial bourgeoisie brought into the turbulence of the twentieth century. Here Renée maintained her salon of musicians, composers and artists, fed and watered by a crew of servants, and kept an eagle-eyed welcome over the comings and goings of her youngest daughter’s motley friends. Her hospitality reached its high point in a garden party for three hundred invitees of the theatre, musical and artistic worlds on 25 June 1921 on the occasion of the Zurich Festival, when guests were ferried from the city down the lake to Bocken. Nobel literature laureate Gerhart Hauptmann and future laureate Hermann Hesse were present. Later musical invitees were Kurt Weill and Wilhelm Furtwängler.

For the children, too, it was a playground: horses, pigs, hens, the nearby lake, skiing and sledding on the hills rising towards the Sihlwald behind the house. With her coeval cousin, Gundalena Wille, Annemarie raced around the grounds on her bicycle – no hands. She attended the local primary school for a brief three weeks in 1916 before being withdrawn due to scarlet fever, following which she was privately tutored.

*

Annemarie Schwarzenbach considered a musical career until mid-adolescence, when her enthusiasm went over to writing. Renée captioned a snap of her daughter with her new music teacher: ‘Annemarie with her love, Fraulein Fischer’15 and from an early age the prodigy’s piano playing won plaudits. By age eleven her playing drew the attentions of the Zurich Festival conductor Arthur Nikisch – Renée stage-managing both festival and daughter. As a teenager, she played Schumann’s Concerto for Piano with aplomb. Music was cherished in the family: her aunt Mathilde had hosted a salon and maintained friendships with musicians and writers. Clara Wille gave Annemarie for her 1925 confirmation a signed copy of Wagner’s piano music which was thought to have come down from Annemarie’s great-grandmother, Eliza Wille.16 Ella Maillart remembered that Annemarie would gravitate towards a piano on the rare occasions that she found one en route to Afghanistan. ‘When she played she became a whole other person. But you know, on our way to Kabul there were few opportunities to play piano.’17

Besides music, Renée cultivated an interest in photography. She liked to dress up the teenage Annemarie and the invariably sullen cast of the model prefigures the unsmiling, posed demeanour Annemarie adopted in the many photographs of her as an adult. In other snaps, a nine-year-old Annemarie is dressed in lederhosen bought in Bavaria on one of Renée’s visits to Emmy Krüger.18 This was the young Annemarie’s favourite attire so much so that she once attended church in it and was promptly ejected by the pastor.19 Perhaps conscious of her gapped teeth, she refrained from smiling in photographs and adopted what her biographer Areti Georgiadou calls her ‘aristocratically suffering facial expression’. Ella Maillart describes Annemarie putting forth ‘a charm that acted powerfully on those who are attracted by the tragic greatness of androgyny’.20 Annemarie’s characteristic and studiedly androgynous look had its origins in the costume cupboard of childhood.

Following a diagnosis of scarlet fever in 1916, Annemarie’s siblings were packed off across the lake to grandmother Clara at Mariafeld and the patient confined to Bocken. Quarantined for many months, mother and daughter recuperated at the spa waters in Rheinfelden. Perhaps as a consequence of this exclusive maternal care, Annemarie developed a propensity for illness – real, attention-getting and imaginary – that was to become a recurring feature in her life and writing. She was home-tutored until the age of fifteen, unlike her older sister Suzanne who attended the Zurich Freie Gymnasium and stayed in the city during the week in the Villa Schönberg with her uncle Ulrich Wille and his wife Inez. Annemarie, however, was enrolled at the Götz-Azzolini private school in Zurich. ‘Mama always found the local Frei Gymnasium terrible even though I got on fine there’,21 recalled Suzanne.

Emmy Krüger noticed early that Annemarie was rebellious, describing in April 1921 the ‘dark paths’ down which Annemarie was treading, causing anxiety to her parents. Annemarie revealed to Krüger’s mother that she hoped to become a writer.22

As a child I had a tendency to write everything down, all that I saw and did, experienced and felt. When I was nine, I wrote my first novel in a school exercise book. And since I knew that nine-year-olds aren’t taken seriously by adults, I made the hero eleven years old.23

Her decidedly rebellious, anti-fascist cast of mind and body had its origins in the 1920s. Mother and daughter subscribed to two diverging views of the German world – Nazi reaction and Weimar freedom – as they played out to disastrous consequences over the decade. A number of the architects of the Nazi blueprint were guests at Bocken and her grandparents’ house at Meilen as Annemarie was growing up. Her mother’s involvement with the Wagner Festival at Bayreuth stoked Renée’s Teutonic heart. As early as October 1920, Munich political geographer and former major-general Karl Haushofer remarked on her enthusiasm for a restoration of German might. A military strategist and orientalist, Haushofer is credited with disseminating German Lebensraum, expansionism by another name, first developed by zoologist Friedrich Ratzel at the turn of the century.24 Haushofer had taught and become friends with Rudolf Hess, soon to be Hitler’s right-hand man. Hess studied for a semester at the ETA, Zurich’s prestigious technical institute, in 1922. Haushofer introduced Hess to Renée and the student was an occasional guest at Bocken. By the time of Hitler’s accession to power, the German Consul-General in Zurich was able to confidently relay Renée’s support for the new regime to his superiors in Berlin: ‘Frau Schwarzenbach, in particular, enthusiastically advocates National Socialism at every opportunity.’25

Dr. Emil Gansser, a chemist working for Siemens, orchestrated Hitler’s two-day fundraising visit to Switzerland in August 1923. Gansser was a keen Nazi supporter, a guest at Bocken well-connected to the chemical and pharmaceutical industries. Hitler stayed at the Gotthard Hotel on Bahnhofstrasse and visited Ully Wille, Renée’s brother, at his Villa Schönberg, where Wagner had written most of Tristan and Isolde, a connection Hitler would have appreciated.26 He had been coached to tone down his anti-semitic harangue among the rich Swiss burgers, and not to stuff his face on the canapés. A strong, stable Germany was in Switzerland’s economic interest and perhaps the ranting little man of humble origins in Bavaria could provide that. Bolshevism in Russia had put the fear of God into the righteous and thrifty Swiss elect. Hitler paid calls on bankers and silk manufacturers, met Schaffhausen industrialist Ernst Homberger, dined at the Baur au Lac, and gave a rallying speech at Ully’s Villa Schönberg. The evening before his departure, along with Dr. Gansser, Hitler dined with General Wille in Meilen. Clara noted in her diary: ‘Hittler [sic] is an exceptionally likeable man. When he speaks, he is really overawing; he speaks wonderfully.’27 Hitler later sent the General and Clara Wille an autographed copy of his book Mein Kampf in recognition of the hospitality he had benefited from in Zurich.28 Historian Alexis Schwarzenbach, based on a letter from his grandfather Hans, believes Hitler also visited Bocken on this occasion and that funds might have passed from Alfred Schwarzenbach to Hitler’s fledgling National Socialism as it took wing.29

Renée’s musical culture inclined towards the Wagnerian and so she was fertile ground for the pop philosophy of National Socialism. The Bayreuth Wagner Festival had become a reactionary symbol of Germany’s former pre-eminence and adopted the kitsch cultural values that Hitler and his nationalists espoused. King Ludwig of Bavaria’s patronage gave the festival a certain high camp among camp followers. Siegfried Wagner, the composer’s son, Ludwig’s godson and festival director, had an ambisexual air about him camouflaged by his wife, Winifred. They married when Siegfried was forty-seven and Winifred seventeen and an English orphan. She became a close friend of Adolf Hitler – her four children knew him as Uncle Wolf. The Wagner Festival opened again in 1924 after a ten-year hiatus; the green hill at Bayreuth had turned distinctly brown and looked towards Germany’s mythological past in all its papier mâché glory. The writer Joseph Roth saw through this Wagnerian flummery: ‘They put up some Wagnerian scenery and give foreigners an operatic song and dance of their politics of vulgar expediency.’30 Many of the organizers were Nazi supporters and Renée, Emmy and the Schwarzenbach girls were annual acolytes. Siegfried and Winifred Wagner, in turn, were invited to Bocken throughout the postwar decade. The Wagners’ potent mix of pan-German völkisch myth, high musical culture and anti-semitism chimed with Emmy’s costume jewellery mind. Renée’s advocacy paid off when Emmy was invited to sing at the festival in August 1924 and in succeeding years.

In August 1924 Renée travelled from Switzerland in a chauffeured car with her mother Clara, her daughters Suzanne and sixteen-year-old Annemarie for the fortnight at Bayreuth. Three generations of the Wille-Schwarzenbach clan were not alone among women from the upper echelons of society and men of a certain stamp who cultivated Wagner’s music. Since the 1880s the festival had been a discreet meeting place for homosexuals during the high summer, for like-minded spirits.31 Siegfried’s personal assistants for nearly a quarter century were a lesbian couple.32 Bayreuth had also become a gathering place for the old war-bedraggled German nobility to lick its wounds and lament its downfall. While Siegfried himself could not be seen to be political, there was no mistaking the message of the festival programme that year: ‘Foreigners, especially the racially less northern types, have no real connection with the art of Richard Wagner – at least not the real Bayreuth connection.’33 Opening night was a performance of Die Meistersinger, directed by Siegfried, in a theatre decorated with the colours of the Wilhelmine Reich. At its conclusion there was a speech about foreign threats and then the audience spontaneously sang all three verses of the national anthem.34 Musicologist Kurt Singer described the new Bayreuth public of 1924: ‘nationalistic and conservative right down to their swastikas, cheering uncritically. … No more than ten non-Aryans attending.’35

Emmy Krüger in Rheinfelden, July 1916. Photo by Renée Schwarzenbach-Wille

Courtesy of Zentralbibliothek Zürich

Photographs of the Schwarzenbach girls at Bayreuth show their cygnet-necked beauty and the New Woman fashions of the day. Suzanne, turning eighteen, will marry the following year. Annemarie had just finished a year at the Götz-Azzolini school in Zurich and was beginning to write her first articles for the Wandervogel magazine. Grown tall and willowy, over the course of three summer visits to Bayreuth she must have turned a few heads. In Lyric Novella her male narrator recalls the theatricality of the festival:

I remembered at the Bayreuth Festival often seeing a special kind of scene change: … mist rose up, diffused by coloured lights, then it grew dense, flowed together in whitish streams and formed walls that became ever more impenetrable behind which the scene sank imperceptibly. Then all was still: the mist dispersed, the stage reappeared and a new landscape emerged, gently tinged with a new light.36

Renée was back again at Bayreuth in August 1925 with husband and family in tow, Annemarie tanned from two weeks in Thun where she had taken dance classes.37 The King of Bulgaria, Prince Hohenlohe and the Countess Schlippenbach graced the festival, and Hitler was there for the first time following an early release from prison. Emmy Krüger played Sieglinde and afterwards the party leader kissed her hand, praised her singing and made remarks about the ‘Jew Schorr’ who had shared the stage with her in the Walkyrie.38 In a letter to her grandmother Clara, Annemarie likewise praised Emmy’s singing and appearance but also enthused over Friedrich Schorr, whom Hitler had, according to Emmy, disparaged, and whom Clara too had dismissed as ‘a total Jew’.39 The casual anti-semitism of the older Wille-Schwarzenbach women took a more virulent stamp with Emmy Krüger. Schorr was one of the great bass-baritones of his time and this spectacle of likes and dislikes underscores how anti-semitism operated in German cultural life in the lead-up to the Nazi reign: race trumped talent as the noose tightened. The spurious notion of the Kulturkammer re-emerged (it had first strutted on the German stage under Bismarck), somewhat like a later generation’s ‘no platforming’, where artists and the public subscribed to a collective agreement as to what constitutes German, no ‘foreigners’ allowed. For German read ‘Aryan spirit’ and for foreign read ‘Jewish’. Musicologist Kurt Singer lost his job in 1933, emigrated to Amsterdam, was interned in Westerbork and deported to Theresienstadt, where he perished. Schorr saw the writing on the wall early and emigrated to the United States in 1931. Annemarie would soon witness the dismantling of whole generations of artistic achievement in Germany, as books were burned and artists were prevented from working. In 1925 the Wagners hosted the Schwarzenbach family and in turn made their way to Bocken for a two-week September stay. The crowning moment of Emmy Krüger’s career at Bayreuth came in 1927 in her role as Isolde. The Schwarzenbach women were back again in force that year to support her.40

*

Nineteen-year-old Suzanne Schwarzenbach married thirty-four-year-old engineer Torgny Öhman on 22 October 1925. She was the first of the family to escape the tensile threads of the cocoon. The groom had been a friend of the family since Suzanne was four and the Schwarzenbachs had visited the Öhmans in Sweden on a number of holidays. Suzanne had become romantically involved during her teens. Annemarie was bridesmaid. The marriage of the first daughter of one of Zurich’s richest men was celebrated with all pomp and circumstance at Bocken. The newly-marrieds departed to live near Stockholm.

Annemarie too was beginning to rustle her wings, and the relationship between mother and daughter grew more fraught and contentious with adolescence. Renée could role play and control the child but, as her growing daughter began to stretch the limits of propriety, there were clashes about the company she kept. In a photograph from September 1925 showing the Wagners at Bocken, Trud Widmer, ‘a friend and admirer of Renée and Emmy’ who lived nearby on the lake, is suggestively holding Annemarie’s hand.41 The gesture and Annemarie’s look give the photograph a defiant edge, clearly aimed at the photographer. The teenager had just been confirmed by Pastor Ernst Merz, with whom she had struck up a friendship and a confiding correspondence. In a letter to Merz, Annemarie described being sent to boarding school at Fetan ‘for moral and health reasons’ and mentions an unhappy love for an unnamed woman.42 Writing to Jacqueline Nougarède, a friend from their time at the Sorbonne, Annemarie makes fond reference to this early love:

Annemarie, age 16, serving at a hunting party, October 1924. Photo by Renée Schwarzenbach-Wille

Courtesy of Zentralbibliothek Zürich

Madame Riedel’s singing in the Corso is a great success! Mme. Riedel is the woman I fell in love with when I was a child of sixteen or seventeen, and maybe she was the best friend I ever had. I loved her passionately, and she loved me, and it was very beautiful. Now she goes around with a Portuguese woman whom I like as well, whose daughter is roped in as ‘a friend of mine’ – it’s funny.43