17,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

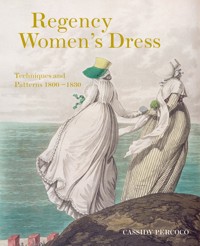

The distinctive style of the Regency period is a source of endless fascination for fashion academics and historians, living historians, re-enactors and costume designers for stage and screen. Author and fashion historian Cassidy Percoco has delved into little-known museum hoards to create a stunning collection of 26 garments, many with clear provenance tied to a specific location, which have never before been published and never – or very rarely – displayed. Most of the garments have an aspect in their construction that has not been previously documented, from a style of skirt trim to the method of gown closure. This practical guide begins with a general history of the early 19th-century women's dress. This is followed by 26 patterns of gowns, spencers, chemises, and corsets, each with an illustration of the finished piece and description of its construction. This must-have guide is an essential reference for anyone interested in the fashions or the history of the period, or for anyone wishing to recreate their own beautiful Regency clothing.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 69

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Regency Women’s Dress

Regency Women’s Dress

Cassidy Percoco

Contents

Introduction

A History of Regency Dress

Chemise 1800–1820

Chemise 1820–1840

Short stays 1795–1805

Corset 1805–1815

Morning Jacket 1800–1815

Spencer 1797–1810

Spencer 1810–1813

Morning Dress 1795–1803

Morning or Evening Dress 1803–1806

Morning Dress c.1800

Morning Dress 1800–1805

Morning or Evening Dress 1803–1805

Evening Dress 1804–1810

Evening Dress 1805–1808

Morning Dress 1809–1818

Quaker Gown 1810–1820

Morning Dress 1813–1816

Evening Dress 1812–1817

Evening Dress 1819–1821

Evening Dress 1818–1820

Formal Dress 1818–1822

Bodice of an Evening Dress 1819–1823

Ball Dress 1820–1825

Morning Dress 1823–1826

Morning Dress 1823–1827

Ball Dress 1824–1827

Acknowledgements

Further Reading

Useful Addresses

Index

Introduction

The Regency period proper began in 1811, with the appointment of the future King George IV, the Prince of Wales, as Prince Regent; it ended in 1820, when he came to the throne. However, the term ‘Regency period’ – or the more accurate ‘long Regency’ – is often used to refer to the later 1790s and the first three decades of the nineteenth century. The dress of this period was characterized by raised waistlines, narrower skirts, and historical influences on fashion; outside of dress, it was knitted together with the upheavals in French politics, the early Romantic movement in poetry and literature, and its similarity in manners and mores as contrasted with those of the Victorian era.

The history of the dress of this period is not well known, often even among fashion historians. It is stereotyped as very high waistlines, white muslin and bonnets – but there was a significant amount of fluctuation and change. For historians and curators, it is important to be able to date garments and portraits in museum collections accurately, in order to keep records well and to determine whether or not the given provenance for an object is likely to be correct. For those who make re-creations of historical dress for film or reenactment, accuracy is less vital but an entertaining aspect of the pastime.

The patterns in this book span the first three decades of the nineteenth century, and have been drawn from garments in smaller museums in New York state. Previous collections of patterns that have included this era, such as Norah Waugh’s The Cut of Women’s Clothes and Janet Arnold’s Patterns of Fashion I, cover a longer period of time and therefore can devote less space to each sub-period: Regency Women’s Dress, containing 26 patterns, is able to show a far greater amount of variation within these decades. The garments, being mainly of American origin, provide a much-needed resource for American academics, who have previously only worked with patterns of British origin. While some aspects of construction and style are near-universal for most Western countries during this time period, there are certain stylistic divergences between Britain and France, in which American women tended to side with their French cousins.

On the patterns, each block in the grid is equivalent to 1in (2.5cm) on the original. The method of scaling up patterns for sewing use preferred by the author is to use the grid as a guide and draw out the individual pieces on a sheet of newsprint or oversized paper, measuring up, down, and over from a set of points. Alternatively the patterns can be enlarged on a photocopier.

A History of Regency Dress

During the early nineteenth century, ‘morning’ was the time between breakfast (usually held sometime between 8am and 10am) and dinner (between 4pm and 7pm): while at home in the morning, a woman would wear a morning dress (robe du matin) or undress (négligée) of an inexpensive fabric like a cotton print or linen, generally with long sleeves, a higher neckline, and a concealing cap. If she were to go out walking or to pay calls, she would put on walking or visiting dress – something of a more expensive fabric, with more embellishment, with a hat or bonnet. If riding, she would wear a riding habit (amazone) made of wool in a dark or drab colour.

A woman might wear full dress or half dress to dinner, depending on the level of formality required: if only the family were dining, if guests were to be present, and so on. Ball dresses (robes du bal) were shorter than full dress, since they were worn for dancing, and during much of this period they were often a light sheer silk fabric, such as gauze or crepe, worn over a taffeta or satin slip (dessous) in either white or the colour of the gown. Flowers, both real and artificial, were often used as decorations both in the hair and on the ball dress.

A timeline of women’s clothing and accessories in the most detailed particulars could occupy the space of dozens of pages, but here I present a shortened version based on my research on extant gowns and French and English fashion plates.

The white muslin chemise gown – loose, draped and fitted mainly by drawstrings – became fashionable in the later 1780s, and when the waistline rose in the mid-1790s the gowns took on an even more Hellenistic air. This was deliberate: Neoclassicism had been in vogue for furniture and architecture for some time, as well as philosophy and political thought, and the time was ripe for it to be expressed through women’s dress. With the higher waist came a new form of stays, shortened at the bottom but at first essentially the same shape as those of the rest of the eighteenth century; fairly soon they developed shaping to give the bust a more rounded and raised appearance, usually separating the breasts far more than is fashionable today. In keeping with the prevailing attitude that a natural beauty was better than the artifices of cosmetics, hooped petticoats or false rumps, fashionable hair could be dressed without powder and with long curls cut in varying layers and a fringe hanging over the forehead. It might also be twisted up into a chignon with loose ends visible at the top of the head, or ‘cropt’ short into a cut à la Titus – a very modern-looking style that nonetheless persisted in fashion through the first decade of the nineteenth century: Jane Austen complained of her niece Anna’s ‘sad cropt head’ in 1808 and 1809.

White was the most fashionable colour for gowns during the late 1790s, often trimmed with bright colours along the hemline and at the ends of the fitted, elbow-length sleeves. White appeared to be the colour of the drapery on Classical statues, it was cool in the summer, it matched all coloured accessories, and it was difficult to keep clean, which gave it an added status boost. The fabric of some white gowns was embroidered on the loom with repeated white motifs, or printed with a geometric pattern. Cotton prints were used, as were coloured silk, but in the most fashionable dress coloured fabrics (generally wool or cashmere) were reserved for outerwear: pelisses (redingotes), long overgowns styled like men’s coats, generally buttoning in front; spencers, jackets that ended at the high waist; douillettes, lighter pelisses that were often shorter than the gowns beneath them, and were styled like gowns; and witzchouras, heavier and looser than pelisses, usually with a fur lining and a hood. Accessories like shawls (square or rectangular), leather shoes, hats and turbans, and ribbon belts also were coloured. One particular style of ribbon belt wrapped around the shoulders and crossed over the back – originally blood red, it was called the ceinture à la victime after the victims of the guillotine, and in various colours it continued to be worn to about 1810.

Some accessories, however, were generally white: the chemisette (guimpe) filled in or covered the neckline of a gown like a sleeveless, short shirt and held a ruffled collar (a demi-guimpe had no collar); the canezou was a light muslin spencer.

The chemise or round gown of the late 1790s and early 1800s generally had a fitted back, and fastened in the front at neck and waist with drawstrings. Open robes that were cut more like earlier eighteenth century gowns, open in the skirt to show a (white) petticoat, were a more formal choice, with noblewomen described in magazines as wearing them to great occasions.