Table of Contents

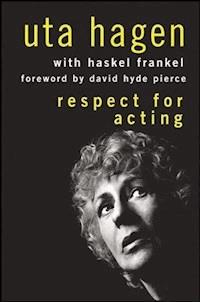

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication

Foreword

Acknowledgements

PART ONE - The Actor

Introduction

Chapter 1 - Concept

Chapter 2 - Identity

Chapter 3 - Substitution

Chapter 4 - Emotional Memory

Chapter 5 - Sense Memory

Chapter 6 - The Five Senses

Chapter 7 - Thinking

Chapter 8 - Walking and Talking

Chapter 9 - Improvisation

Chapter 10 - Reality

PART TWO - The Object Exercises

Introduction

Chapter 11 - The Basic Object Exercise

Chapter 12 - Three Entrances

Chapter 13 - Immediacy

Chapter 14 - The Fourth Wall

Chapter 15 - Endowment

Chapter 16 - Talking to Yourself

Chapter 17 - Outdoors

Part One

Part Two

Chapter 18 - Conditioning Forces

Chapter 19 - History

Chapter 20 - Character Action

PART THREE - The Play and the Role

Introduction

Chapter 21 - First Contact with the Play

Chapter 22 - The Character

Chapter 23 - Circumstances

Chapter 24 - Relationship

Age

Chapter 25 - The Objective

Chapter 26 - The Obstacle

Chapter 27 - The Action

Chapter 28 - The Rehearsal

Chapter 29 - Practical Problems

Performer’s Nerves

“How Do I Get a Job?”

Auditions

“Do You Think I Have Talent?”

“How Can I Work Correctly in Summer Stock?”

“Should I Stick It Out in the Theater?”

“What about the Pacing? The Rhythm? The Tempo?”

“Do You Think I Was Overacting?”

“How Do I Stay Fresh in a Long Run?”

“How Do I Work with a Replacement in the Cast?”

“How Do I Talk to the Audience?”

Accents and Dialects

Dressing the Part—the Costume and Makeup

Moral Standards

Chapter 30 - Communication

Chapter 31 - Style

Epilogue

Index

Copyright © 1973 by Uta Hagen. All rights reserved Foreword copyright © 2008 by David Hyde Pierce

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and the author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

For general information about our other products and services, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (800) 762-2974, outside the United States at (317) 572-3993 or fax (317) 572-4002.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. For more information about Wiley products, visit our web site at www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Hagen, Uta, date.

Respect for acting / Uta Hagen, with Haskel Frankel. p. cm.

Originally published: New York : Macmillan, 1973.

Includes index.

eISBN : 978-0-470-73018-8

1. Acting. I. Frankel, Haskel. II. Title.

PN2061.H28 2008

792.02’8—dc22

2008016843

To Herbertwho revealed and clarified andhas always set me a soaring example

Foreword

by David Hyde Pierce

I had the life-changing experience of acting with Uta Hagen in a two-person play a few years before she passed away. I was excited to be working with this legendary actor and teacher, but also daunted by the prospect of being the only other person on stage with her, so I re-read her books, both to prepare for my role and to prepare for her.

Well, nothing could prepare you for Ms. Hagen. When we met she was in her early eighties and still a force to be reckoned with. She was demure, passionate, charming, ferocious, tireless, and theatrical. As a student of her writing, that was the biggest surprise for me—everything she did was real, and grounded, and deeply human, but she had an extravagance of gesture, a physical and vocal lyricism that had its roots in an earlier era.

She really did practice what she preached about the physical life of a character. She insisted that we have the actual set-pieces and props, even kitchen appliances, in the rehearsal room. No cardboard mock-ups for her—“I want to have opened and closed that refrigerator door a hundred times before I set foot on the stage,” she said. All through rehearsals we used a cruddy old plastic take-out container to hold the cookies she’d serve me in act II. On the day we moved into the theater, the designer had replaced it with a fantastic metal cookie tin which was in every detail exactly the sort of thing the character would have had in her kitchen. Ms. Hagen took one look at it, called it a name, and hurled it into the wings. We used the plastic cookie container for the run of the show.

Her obsession with these details was neither frivolous nor selfish. She was a generous actor, the reality she created for herself on stage was contagious, and acting with her you felt both safe and free. I remember a scene in which I had a speech about losing my mother to Alzheimer’s disease. I felt the speech needed to be emotionally full, and because my own mom had passed away, and I’d lost family to Alzheimer’s, I never had to use substitutions—the emotion was always there for me. But one night as I began the speech I sensed that the emotion wasn’t coming. I might have panicked, or tried to force it or fake it, but sitting there talking to Uta I didn’t want or need to be false. I thought of her advice not to try and pinpoint when or how emotion will come (emotional memory, page 51, item 2), I knew she would accept whatever I gave her, and I went on to the end of the speech, dry as a bone. Then I stood, began my next line (something innocuous like “Would you like a glass of water?”), and came completely undone. As we were walking off stage after the scene, she turned to me with a twinkle in her eye and said, “That was interesting.”

You should know that Ms. Hagen disowned Respect for Acting. After she wrote it, she traveled around the country visiting various acting classes and was horrified by what she saw. “What are they doing?” she’d ask the teacher. “Your exercises” was the proud response. So Ms. Hagen wrote another book, Challenge for the Actor, which is more detailed and perhaps clearer, and should certainly be read as a companion to this. She hoped it would replace Respect for Acting, but it hasn’t, and I think the reason this book endures is that it captures her first, generous, undiluted impulse to guide and nurture the artists she loved.

In this book, you will hear Ms. Hagen’s voice and catch a glimpse of who she was. She wanted us actors to have so much respect for ourselves and our work that we would never settle for the easy, the superficial, or the cheap. In fact, she wanted us never to settle, period, to keep on endlessly exploring, digging deeper and aiming higher, in our scenes, in our plays, in our careers. Respect for Acting is not a long book, and with any luck, it will take you the rest of your life to read it.

Acknowledgments

I want to thank Dr. Jacques Palaci who helped me with his scientist’s knowledge in many areas in which I need further enlightenment and understanding about human motivation, behavior and psychological problems.

PART ONE

The Actor

Introduction

We all have passionate beliefs and opinions about the art of acting. My own are new only insofar as they have crystallized for me. I have spent most of my life in the theater and know that the learning process in art is never over. The possibilities for growth are limitless.

I used to accept opinions such as: “You’re just born to be an actor”; “Actors don’t really know what they’re doing on stage”; “Acting is just instinct—it can’t be taught.” During the short period when I, too, believed such statements, like anyone else who thinks that way, I had no respect for acting.

Many people, including some working actors, who express such beliefs may admire the fact that an actor has a trained voice and body, but they believe that any further training can come only from actually performing before an audience. I find this akin to the sink-or-swim method of introducing a child to water. Children do drown and not all actors develop by their mere physical presence on a stage. A talented young pianist, skillful at improvisation or playing by ear, might be a temporary sensation in a night club or on television, but he knows better than to attempt a Beethoven piano concerto. The pianist’s fingers just won’t make it. A “pop” singer with an untrained voice may have a similar success, but not with a Bach cantata. The singer would rip his vocal chords. An untrained dancer has no hope of performing in Giselle. The dancer would tear tendons. In their attempt they will also ruin the concerto, the cantata, and Giselle for themselves because, if they eventually are ready, they will only remember their early mistakes. But a young actor will unthinkingly plunge into Hamlet if he has the chance. He must learn that, until he’s ready, he is doing the same destructive thing to himself and the role.

More than in the other performing arts the lack of respect for acting seems to spring from the fact that every layman considers himself a valid critic. While no lay audience discusses the bowing arm or stroke of the violinist or the palette or brush technique of the painter, or the tension which may create a poor entre-chat, they will all be willing to give formulas to the actor. The aunts and agents of the actor drop in backstage and offer advice: “I think you didn’t cry enough.” “I think your ‘Camille’ should use more rouge.” “Don’t you think you should gasp a little more?” And the actor listens to them, compounding the felonious notion that no craft or skill or art is needed in acting.

A few geniuses have made their way in this sink-or-swim world, but they were geniuses. They intuitively found a way of work which they themselves were possibly at a loss to define. But even though we can’t all be so endowed, we can develop a higher level of performing than the one which has resulted from the hit-or-miss customs of the past.

Laurette Taylor became a kind of ideal for me when I saw her play Mrs. Midget in Outward Bound. Her work seemed to defy analysis. I went to see her again and again as Mrs. Midget and later as Amanda in The Glass Menagerie. Each time, I went to study and to learn, and each time I felt I had learned nothing because she simply caught me up in her spontaneity to the point of eliminating my own objectivity. Years later, I was excited to read the biography Laurette by her daughter Marguerite Courtney, and to learn that already at the turn of the century, her mother had found a way of breaking down her roles in a way which closely paralleled the principles in which I had come to believe. Laurette Taylor began her work by constructing the background of the character she was going to play. She worked for identification with this background until she believed herself to be the character, in the given circumstances, with the given relationships. Her work didn’t stop until, in her own words, she was “wearing the pants” of the character! She spent rehearsals in exploring place, watching the other actors like a hawk, allowing relationships to grow, considering all possibilities for her behavior. She refused to memorize her lines until they were an integral part of her stage life. She refused to deliver fast results. She revolted against stage convention and imitation. And after all of this, she still insisted she had no technique or method of work.

It is said that the Lunts reject “method” acting, and yet I had an experience with them that went beyond the method of most “method” actors. In the last act of Chekhov’s The Sea Gull, during the big scene between Nina and Konstantin, the rest of the household is supposed to be eating supper in the adjoining room. Mr. Lunt and Miss Fontanne worked tirelessly on this offstage supper scene, improvising dialogue, deciding what food they would be eating, searching for their behavior during this meal. In performance, when the Lunts left the stage, they actually sat down at a dinner table in the wings, ate food, chatted, and reentered with the reality of having had a meal. No one in the audience caught a glimpse of it, but they did get the clink of china and glass and silverware, and the muted offstage dialogue as a brilliant counterpoint to the tragic onstage life. And the actors got a continuity of their existence.

Paul Muni also denied a “method” of work in developing a character. Yet in actual practice he sometimes went to live for weeks at a time in a neighborhood where his character might have lived or been born. Mr. Muni went through a process of research and work which was so deep, so subjective, that it was sometimes torturous to watch.

We may forget that Stanislavsky went to the finest actors of his day and observed them and questioned them about their approach to their work, and from these findings he built his precepts. (He didn’t invent them!)

One of the finest lessons I ever learned was from the great German actor Albert Basserman. I worked with him as Hilde in The Master Builder by Ibsen. He was already past eighty but was as “modern” in his conception of the role of Solness and in his techniques as anyone I’ve ever seen or played with. In rehearsals he felt his way with the new cast. (The role had been in his repertoire for almost forty years.) He watched us, listened to us, adjusted to us, meanwhile executing his actions with only a small part of his playing energy. At the first dress rehearsal, he started to play fully. There was such a vibrant reality to the rhythm of his speech and behavior that I was swept away by it. I kept waiting for him to come to an end with his intentions so that I could take my “turn.” As a result, I either made a big hole in the dialogue or desperately cut in on him in order to avoid another hole. I was expecting the usual “It’s your turn; then it’s my turn.” At the end of the first act I went to his dressing room and said, “Mr. Basserman, I can’t apologize enough, but I never know when you’re through!” He looked at me in amazement and said, “I’m never through! And neither should you be.”

The influences on my development, aside from the master artists I observed or worked with, have been numerous. In my parents’ home, creative instincts and expression were considered worthy and noble. Talent went along with a responsibility to it. I was taught that concentrated work was a thing of joy in itself. Both my parents lived such a life and set this example for me. They also showed me that a love of work is not dependent on outward success.

I am grateful to Eva Le Gallienne for first believing in my talent, for putting me on the professional stage, for upholding a reverence for the theater, for helping me to believe that the theater should contribute to the spiritual life of a nation. I am grateful to the Lunts for endowing me with a rigorous theater discipline which is still in the marrow of my bones.

I had a strange transition from amateur to professional. The word “amateur” in its origin was a lover or someone pursuing something for love. Now it is synonymous with a dilettante, an unskilled performer, or someone pursuing a hobby or pastime. When I was very young and then when, still young, I was employed in the theater, I was an amateur in its original sense. I pursued my work for love. Then, the fact that I was paid was incidental to the love. At best, being paid meant that I was taken seriously in this love of my work. Undoubtedly I was unskilled. My strength as an actor rested in the unshakable faith I had in make-believe. I made myself believe the characters I was allowed to play and the circumstances of the characters’ lives in the events of the play.

Inevitably, in the learning and turning process from amateur to professional, I lost some of the love and found my way by adopting the methods and attitudes of the “pro.” I learned what I now call “tricks” and was even proud of myself. I soon learned that if I made my last exit as Nina in The Sea Gull with full attention on the whys and wherefores of my leave-taking, with no attention to the effect on the audience, there were tears and a hush in the auditorium. If, however, I threw back my head bravely just as I got to the door, I received a round of applause. I settled for the trick which brought the applause. I could list pages of examples of acquiring “clean entrance” techniques, manufactured tears and laughter, lyric “qualities,” etc.—all the things to do for calculated outer effects. I thought of myself as a genuine professional who had nothing more to learn, just other parts to make effective. I began to dislike acting. Going to work at the theater became a chore and a routine way of collecting my money and my reviews. I had lost the love of make-believe. I had lost the faith in the character, and the world the character lived in.

In 1947, I worked in a play under the direction of Harold Clurman. He opened a new world in the professional theater for me. He took away my “tricks.” He imposed no line readings, no gestures, no positions on the actors. At first I floundered badly because for many years I had become accustomed to using specific outer directions as the material from which to construct the mask for my character, the mask behind which I would hide throughout the performance. Mr. Clurman refused to accept a mask. He demanded me in the role. My love of acting was slowly reawakened as I began to deal with a strange new technique of evolving in the character. I was not allowed to begin with, or concern myself at any time with, a preconceived form. I was assured that a form would result from the work we were doing.

During the performance of the play, I discovered a new relationship to the audience which was so close, so intimate, that I thanked Harold Clurman for breaking down the wall which had so often separated me from the audience.

I went on to explore more deeply with Herbert Berghof what I had begun to learn from Harold. Herbert gave me painstaking help in how to develop and make use of these discoveries, how to find a true technique of acting, how to make a character flow through me.

The American theater poses endless problems for any actor who wants to call himself an artist, who wants to be part of an art form. From the very beginnings of “doing the rounds” of agents, producers and directors; through the terrifying audition procedures; to the agonies of attempting to prove yourself, in early rehearsals; to the sense of compromise you feel in yourself, your fellow actors, the playwright, from the first rehearsal through the out-of-town tryouts to the opening night in New York; to the acceptance of the public and the critics; to the element of speculating about whether you will close on Saturday or work for years, or possibly never work again—these things make for conditions which periodically have disillusioned me about the Broadway theater, about my own work, about directors, about playwrights, about management, about every phase of my chosen profession. The only place where I have known a degree of fulfillment is at the HB Studio, where I am both teacher and learn from others.

I am lucky to have found this place where I can put a degree of my struggle for growth, my search for the miracle of reality in acting into practice. The HB Studio was founded by my husband, Herbert Berghof. We both teach there. We act there with our students and other fellow actors. We direct there. We work on plays and scenes which the commercial theater cannot afford or will not foster.

As a teacher, in view of the pages that follow, let me state what to me is not modest, but obvious. I am not an authority on behaviorism or semantics, not a scholar, a philosopher, nor a psychiatrist, and I am frankly fearful of those who profess to teach acting while plunging into areas of actors’ lives that do not belong on a stage or in a classroom. I teach acting as I approach it—from the human and technical problems which I have experienced through living and practice.

I believe in my work and in what we are doing at the HB Studio. I pray that with patience and foresight a first-rate acting company will develop out of the Studio, a company guided by first-rate young directors, and, hopefully, young playwrights. When this happens, it will be a company of people who have grown together, who are united by common aims and by a way of work which has a common language and results in a homogeneous form of expression. The four walls to house such a group will follow, and then perhaps we will be able to make a real contribution to the American theater. But should it never happen, it will still be a goal worth working for!

1

Concept

If you have the opportunity to visit the Museum of Modern Art in New York City when they are showing the film series “Great Actresses,” you will see performances by Sarah Bernhardt and Eleonora Duse among others. Both actresses lived and acted at the same time; both were considered great. Yet their approach to acting differed. Sarah Bernhardt was a flamboyant, external, formalistic actress, reflecting the fashion of her time. Duse was a human being on stage. Today, Bernhardt’s mannerisms make you laugh. Duse moves you; she is more modern than tomorrow.

I mention these two ladies from the past in a book meant for the actor of today because they represent two approaches to acting that have been debated in the theater through the centuries. The two approaches have names that annoy and confuse me, but since you will hear them again and again, let me name them now, and hopefully get rid of them. One is the Representational (Bernhardt), the other the Presentational (Duse).

The Representational actor deliberately chooses to imitate or illustrate the character’s behavior. The Presentational actor attempts to reveal human behavior through a use of himself, through an understanding of himself and consequently an understanding of the character he is portraying. The Representational actor finds a form based on an objective result for the character, which he then carefully watches as he executes it. The Presentational actor trusts that a form will result from identification with the character and the discovery of his character’s actions, and works on stage for a moment-to-moment subjective experience.

For an example of the above, let me again refer to Bernhardt and Duse. Each, in her native tongue, had played the same popular melodrama of the time, the high point of which was the moment when the wife, accused of infidelity by her husband, swore her virtue. “Je jure, je jure, JE JUUUUURE!” Bernhardt proclaimed in a rising vibrato of passion. Her audience stood to scream and shout its admiration. Duse swore her virtue softly and only twice. She never spoke the third oath, but placed her hand on her young son’s head as she looked directly at her husband. Duse’s audience wept.

One night, after having received accolades for his performance from the audience, the nineteenth-century French actor Coquelin called his fellow actors together backstage and said: “I cried real tears on stage tonight. I apologize. It will never happen again.” His approach to acting was obviously Representational. For him, a genuine experience on stage was rejected in the belief that it would muddy or blur the acting.

I believe that the illustration of a character’s behavior at the cost of removing one’s own psyche, no matter how brilliant the performance that results, creates an alienation between audience and actor. The audience may yell “Bravo!,” they may even rise to their feet and cheer, but they are reacting in the same manner they would to an acrobat or a high-wire performer—they are cheering the visible skill, they are applauding the feat pulled off. But the vital empathy with human behavior, the emotional involvement between actor and audience will be lacking.

Formalized, external acting (Representational) has a strong tendency to follow fashion. Internal acting (Presentational) rejects fashion and consequently can become as timeless as human experience itself.

I think now you know where I stand. Certainly it is with the Duse who, once accused of being too much alike in each of her roles, answered that as an artist the only thing she had to offer was the revelation of her soul. But if I stand with Duse and with the Presentational approach to acting, I do not reject in toto the Representational. To do so would be to reject actors of brilliance who have found their way along that path. I reject the Representational only for myself, as actress and teacher. I must work on an approach to the theater that functions for me. As a teacher I can teach only what I believe.

For a would-be actor, the prerequisite is talent. You can only hope to God you’ve got it. Talent is an amalgam of high sensitivity; easy vulnerability; high sensory equipment (seeing, hearing, touching, smelling, tasting—intensely); a vivid imagination as well as a grip on reality; the desire to communicate one’s own experience and sensations, to make one’s self heard and seen.

Talent alone is not enough. Character and ethics, a point of view about the world in which you live and an education, can and must be acquired and developed.

Ideally, the young actor should possess or seek a thorough education in history, literature, English linguistics (foreign languages are so much gravy), as well as all of the other art forms—music, painting and dance—plus theater history and orientation.

Essential to a serious actor is the training and perfecting of the outer instrument—comprising his body, his voice and his speech. This instrument is the violin on which he will play. He should be aware that it can be comparable to a Stradivarius and that he must turn it into and treat it like one.

Since voice, speech and body work are not in my realm as a teacher, I must simply assume that any actor serious enough to read this text will never cease to develop his physical capacities through dancing, fencing, gymnastics, etc., or work for the mastery of voice production and correct standard speech. All parts of his instrument should be limber enough to respond to the psychological and emotional demands he may make on it when he springs into physical and verbal action in the character in the play. A young actor who fails as Romeo—no matter how brilliant his inner technique—because he hasn’t been able to shed his Brooklyn speech or his pigeon-toed walk, has only his own laziness to blame.

Physical beauty is not a prerequisite to becoming an actor. Few of our present-day stars are physically beautiful in the conventional sense. However, the best of them, men and women, can create beauty for an audience. If you think of a beautiful baby you may remember that it graciously accepts the admiration which comes to it voluntarily. The homely baby must reach out to others and quickly learns from necessity to clown and do a hundred things to win attention. The homely baby learns what the actor must learn to say through his art, “Here I am, look at me!” The physically beautiful actor is often cursed with the passivity of easy conquest. He accepts and expects everyone to come to him, instead of reaching out to them.

Mental brilliance is not essential. An intellectual actor can intellectualize himself out of real acting impulses, while his less mentally endowed brother, provided he is not dull and insensitive, may function magnificently if he has understanding of human behavior. (By this I do not mean to imply that if you are highly intelligent or exquisitely beautiful you don’t stand a chance in the theater.)

It is necessary to have a point of view about the world which surrounds you, the society in which you live; a point of view as to how your art can reflect your judgment.

To rebel or revolt against the status quo is in the very nature of an artist. A point of view can result from the desire to change the social scene, the family scene, the political life, the state of the ecology, the conditions of the theater itself. Rebellion or revolt does not necessarily find its expression in violence. A gentle, lyric stroke may be just as powerful a means of expression. To portray things the way they are, to hold up a mirror to the society, can also be a statement of rebellion. You must ask yourself, “How can I bring all of this to the statement I wish to make in the theater?”

When you have decided what it is you wish to express, you must decide what kind of a theater you would ideally want to be a part of. And now your real problems begin!

Many other fields of artistic endeavor offer the choice of working as an artist or as a commercial craftsman. As it stands now, our theater is by its very set-up commercial. The finest and deepest play on Broadway has been produced to make money, not just to serve, enlighten or enrich the lives of those fortunate enough to afford the price of a ticket. If the play does serve, that’s so much velvet and extremely rare. If you have decided to become a commercial actor (an honorable profession to which I attach no stigma) you will have endless practical problems in the theater, television and films. But if you want to be a serious theater artist, these problems will be multiplied endlessly by emotional frustrations, guilts and longings.

In the late 1950’s, Jean Louis Barrault complained about the theater in France. He said that it was too much like Broadway in that the theaters were becoming like garages. At first I thought he meant dirty and overcrowded. Then I realized he meant the theaters were simply being hired as space to park in for a while, instead of representing your theater, your home with its own identity where all of the productions should express your point of view about the world in which you live; in which you could even reveal your soul (Duse) through art.

Barrault had a romantic, liberal, slightly mystical point of view in his own Theatre which manifested itself in his choice of plays and his conception for presentation, as opposed to, let’s say, the Socialist, political Theatre Nationale Populaire of Jean Villard and Gérard Philipe, or the traditional, academic approach of the Comédie Française. All three subsidized theaters played simultaneously in Paris for many years along with other groups who had their own points of view. Sometimes, more than one theater produced the same play at the same time, but each with its own distinct viewpoint. Barrault feared that these individualistic theaters were threatened by the “commercial” circumstances encroaching on the Parisian theatrical scene.

In America we don’t even know what Barrault feared. Our theater with a point of view isn’t threatened because it has never existed except in the minds of individual artists. Consequently, we have no true theater-going tradition. The theater is still not a part of our lives, not a necessity, not a sustenance for our spiritual lives. We actors have never had a “home” as Barrault understood it.

West Germany has over 275 subsidized repertory theaters, and West Germany is smaller than the state of Wisconsin. Its theaters are subsidized by the state, the municipality, industry and labor. The people expect this subsidy. They revere and honor the artist who serves in the theater—for a living wage, but not huge amounts of money. In America, our audiences, friends, families and neighbors think we are no good if we work for less than fortunes. Yet, surely, the compensation of respect is far greater than money.

In the United States, we have had a number of theaters with a point of view that almost made it—or they made it for several years. Many years ago we had the Provincetown Players, the early Theatre Guild, the Civic Repertory and the Group Theater. Since then, each decade has brought us further attempts in the establishment of meaningful and permanent companies. I’m sure you are familiar with many of them. The eventual failure of these noble ventures has almost always been connected with the success of one or more individuals who scored and then left to go on to a personal success in a film or commercial play. The venture that had served them was left behind, just a launching pad to be abandoned by those who had used it to reach personal heights. The potential of these theaters was devoured by the commercial theater.

Countless other ventures have wondered why they failed to acquire their own audiences. Their purpose is often simply to do “good” plays. Usually they present these good plays without any point of view reflecting the problems of the day. They should stop wondering and make their own statement. They will find their audience.

To maintain one’s ideals in ignorance is easy; to maintain them with the full realization of the existing circumstances is not. To accept “the way it is” is the opportunistic way out or the way of the ostrich; to attempt to battle it takes knowledge and character.

I have often heard both professional, working actors and young beginners proclaim with passion, “I want to be the best actor in America!” But what is that? Merely a statement of a competitive goal. It epitomizes the American disease of ambition for success—accompanied by fame and fortune—as proof of worth. Steak, chicken, lobster, lamb are all delicious but which is best? One may be the favorite of a certain group, but others have a different preference. Who is best among Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven? These three musical giants worked and created in Vienna at the same time. We may prefer the music of one composer to that of another, but there is no best. Each worked to create his own best, not to be the best.

A prominent actress once said to me: “I get so confused. Who am I trying to reach? The gas-station attendant or Brooks Atkinson?” She didn’t understand that they both have needs for an offering, for sustenance. I explained to her that I was confused for a while when I got rave reviews in The Sea Gull. They went straight to my head and stayed there until I attended a matinee of another young actress who had received equally good reviews. In my judgment her performance was poor. I was forced to reevaluate my thinking. If I dismissed the critical raves for one actress, what value could I place on my own? Who, ultimately, outside myself and a few of my peers whose opinion I valued, was to be the judge of my work? I began to learn to work for standards designed neither for the gas-station attendant nor Brooks Atkinson, but for my own. Set your own goals, set them for your own approval, and those of your colleagues whom you truly respect.

By the very nature of our profession we seem to develop slothful rather than disciplined habits. A great dancer to his last days cannot—and will not—perform without hours of daily practice. The pianist Artur Rubinstein and the violinist Isaac Stern cannot—and will not—play a concert without daily practice. While an actor may be forced to work as a waiter or a typist to sustain himself while waiting for the call to play King Lear, there is no excuse for his frittering away the hours that belong to him—and his true work—with partying, and fun and games.