Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Royal Bargemasters have been serving their monarchs for over 800 years, yet their story has never been told. Always working in close proximity to their sovereigns, they have witnessed and played their part in many of the important events in our country's history. They have been close witnesses to rebellions and coronations, to initial courting and grand royal weddings, and added their colourful presence to the splendour of celebrations and pageants. Painstakingly researched by ex-Royal Bargemaster Robert Crouch and professional researcher Beryl Pendley, this beautifully illustrated book offers a colourful insight into the role of the Bargemasters over the centuries, revealing the part they have played in both the day-to-day lives of the Royal Family and their contribution to great ceremonial occasions from the Plantagenets to our present Queen.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 253

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

HM the Queen hosting a family tea party on board Gloriana at Windsor Park, 2013. (Picture by kind permission of Malcolm Knight Gloriana Trust)

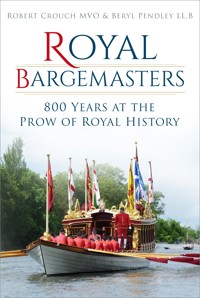

Front cover: Gloriana with HM Bargemaster and full crew delivering the Stela in the Tudor Pull, 2018. (Picture by kind permission of John Adams)

Back cover: J.A. Messenger, with R. Turk on the right and W. Biffin on the left. (Picture from the Turk family collection)

First published 2019

The History Press

97 St George’s Place

Cheltenham, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Robert Crouch MVO and Beryl Pendley LL.B, 2019

The right of Robert Crouch MVO and Beryl Pendley LL.B to be identified as the Authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9275 6

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Dedication

Foreword by HRH Earl of Wessex

Author’s Note

Preface

Acknowledgements

I

A Brief History of the Royal Bargemasters

II

Development of the Role of the Royal Bargemaster

III

Royal Bargemasters Since Edward I

IV

Bargemasters to HM Queen Elizabeth II

V

The Royal Family Afloat

VI

Appointments, Uniforms and Wages

VII

Keeping it in the Family

VIII

Bargehouses

IX

Royal Barges

X

Palaces and Landing Places

Notable Events for HM Bargemasters and Royal Watermen

Glossary

Research Sources

Notes

About the Authors

DEDICATION

The authors wish to dedicate this book to Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II in recognition of her rejuvenation and enrichment of the role of Her Bargemasters and Watermen during her long reign.

Since her ascension to the throne in 1952 and her first use of the Royal Barge to visit Greenwich in 1953, through to the magnificent river pageants for her Silver, Golden and Diamond Jubilees, Her Majesty has used her Royal Bargemasters and Watermen on numerous occasions, both on the upper reaches and on the tidal reaches of the Thames.

During the many decades of neglect and misuse of London’s river in Victorian times and the dark days of the World Wars, before Her Majesty came to power, the Thames became polluted and was used less and less to stage events. However, during her reign the river was brought back to life, and is now cleaner, with an abundance of fish returning to its waters. Since her coronation, our Queen has, through six successive Bargemasters, refreshed Royal use of London’s natural showplace.

Her support, and that of the Duke of Edinburgh, has meant that untold numbers of people have benefited from using the river for sport, display and to witness spectacular events, meaning that all can once again appreciate the importance of London’s great natural asset: the Thames.

HM Bargemaster’s plastron worn back and front of uniform. (Picture by Reflections Photography, with permission of Buckingham Palace)

FOREWORD BY HRH EARL OF WESSEX

Some years ago, I had the privilege of experiencing what it was like to be rowed on the River Thames by the Royal Watermen. On that occasion we used the Royal Shallop Lady Mayoress, a 40ft shallow drafted rowing boat with a crew of seven, typical of the sort of vessel the gentry would use. It was a hint of days gone by when the Thames was the main thoroughfare through London and taxis were rowing boats called wherries, hailed by calling ‘Oars!’

Britain has had a monarchy for over 1,000 years and for most of that time Royal Bargemasters and Watermen have been responsible for ferrying our Kings and Queens up and down the River Thames as well as protecting them. The river was by far the safest and most efficient means of travel and it’s no coincidence that most of the Royal Palaces and Residences were built on the banks.

The story of the Royal Bargemasters and their long association with the Crown is as much about the Thames as it is about their Royal passengers. Huge congratulations must go to Robert Couch for embarking upon this personal journey to discover more about his predecessors in the role, and grateful thanks to Beryl Pendley for undertaking so much of the research. The result is a brilliant insight into a unique piece of history. Sadly Mrs Pendley died of a sudden illness before this book was published.

As with our monarchy, it’s not just about the past. A couple of years ago I experienced the latest Royal Row-Barge, Gloriana, a far cry from the Royal Shallop. This magnificent vessel requires eighteen very fit oarsmen and a very proficient helmsman. It’s a wonderful way to travel, but you do need to provide a little notice of your intention!

This book also recommends itself as groundwork for any future research into this fascinating subject and helps to fill one of the gaps in the wonderful and colourful history of our country.

HRH Earl of Wessex, KG, GCVO30 March 2019

AUTHOR’S NOTE

By R.G. Crouch MVO

After serving over twenty years in the Royal Household, eight as a Royal Waterman and twelve as Her Majesty’s Bargemaster, I became intrigued at how little had been written about the origin of these unique ancient appointments, which are so cherished within the Thames community. The more I searched back into the history, the more I realised how little had been recorded. Then during my time as temporary Clerk to the Watermen’s Guild, I discovered a short piece in the Henry Humpherus Watermen’s History that encouraged my obsession and triggered a determination to fill this gap in the history and origins of Royal Bargemasters and Watermen. The Humpherus entry is as follows:

The disputes between King John (who was then at Windsor) and his Barons, led to a conference to consider their grievances, being appointed. It took place on the 15th of June, at Runnemeade, (anciently called Running Meade) on the banks of the Thames, between Staines and Windsor, a place which has ever since been celebrated on account of this great event. The island by the upper end of it bears the name of. Magna Charta. Many of the barons and their followers proceeded to the spot appointed, in their barges and boats, and the two parties encamped apart like open enemies, (the country between Staines and Windsor was white with the tents of the ironclad men, who had come to demand a charte : of liberties) and after a debate of a few days, the King on the 19th of June, signed and sealed the Deed of Magna Charta, which was required of him. This famous deed, containing forty-nine clauses, either granted or secured very important liberties and privileges to every order of men in the kingdom, and clause twenty-three may be mentioned as providing that all kydells [fish weirs]for the future shall be quite removed out of the Thames and Medway. On the meeting breaking up, notice of the completion of the charter by the King was received with much enthusiasm by the assembled multitudes. The river was blocked up with the splendid barges of the nobility and others, the owners thereof getting away as fast as the embarkation could be effected.

Henry Humpherus, Book One, 1215

I now felt that I had a starting date of at least 1215 when the nobility were using the river in lavishly appointed barges.

My research being limited to the records at Watermen’s Hall and the City’s Guild Hall library, it was suggested by the Privy Purse Office at Buckingham Palace that I should contact the archivists at Windsor. However, on contacting them I was told that their records on the subject were at best ambiguous and only went back in any detail to the Victorian era. Everyone I spoke with agreed that the story went much further back in time and that it needed to be expertly investigated. I soon realised that I was out of my depth and needed help from a professional researcher.

Like all worthy stories, it was a piece of good fortune that changed my luck. Some years earlier I had reason to go to the College of Arms, which led to a meeting with Mrs Beryl Pendley, who was Assistant to Rouge Croix Pursuivant of Arms and was also taking her Bar Finals. She was very interested in the fact that I was involved with the Royal Watermen and we struck up an ongoing friendship.

We kept in touch intermittently and in later years I found that Mrs Pendley was now a professional ancestral researcher and had sustained her interest in the Royal Watermen. Upon hearing of my predicament, she offered to help with some appropriate research. The outcome was an agreement to work together on producing an authoritative book on the origins and progress of Royal Bargemasters. The subject has proved to be so intriguing that we have had to discipline ourselves to using research concerning only Royal Bargemasters and not be tempted into the many seductive offshoots of this subject.

There followed many years of difficult and time-consuming examination of the records at the various centres of archives in and around London to produce the raw data, which then had to be analysed and written up into a readable format. This book is the outcome of Mrs Pendley’s work and our joint authorship, which we hope will be informative and which may prove useful to future writers on this subject matter.

For myself, it is a great relief to have achieved one of the aims of my river career by recording a first history of this obscure yet loyal group of men.

Robert George Crouch MVO

OBITUARY TRIBUTE

It is with great sadness that I report the death of my co-author Beryl Pendley who died of a sudden illness in early March 2019 while this book was being prepared for publication. Beryl was the person who persuaded me to continue with this book when I became overwhelmed by the amount of research required, who then joined me and used her skills as a professional researcher to seek out detailed information from the many obscure sources involved.

Beryl became fascinated with the book’s subject matter and was rightly proud of her discoveries over the three years it took to complete her research. She was extremely determined and fastidious and kept us both on target by avoiding the many fascinating offshoots which we were tempted to follow up.

Although she was unable to see the finished product, she did see the various drafts and the final cover page image and was delighted when I was able to tell her that HRH Prince Edward Earl of Wessex had agreed to write a foreword to the book.

She will be sadly missed by her partner Eugene, her sons James and Royston and her beloved dogs. I will miss her as a mentor, friend and fellow author and I hope that her cheerful character will show through to the readers of this book.

Rest in peace merry Beryl.

Bob Crouch.

PREFACE

The reason for having a Royal Bargemaster and the Royal Watermen is to transport the monarch on water in a way that is fast, safe and comfortable, whilst at the same time offering an opportunity to display authority and majesty.

Over the centuries, the back-facing, seated mode of rowing was found to be the most efficient, but given the importance of the passenger, a particularly experienced waterman was needed to be facing forward to steer and pilot the vessel. This special waterman became the Royal Bargemaster.

As will be seen in the book, the Thames can be a difficult river to negotiate, made even more so in earlier centuries by Old London Bridge, which at certain tide times required great skill to negotiate safely.

Of course other methods of transport were available to the monarch – riding and carts or carriages. As we know, monarchs rode long distances throughout the country when necessary, especially where no rivers were available for water transport. Most of our monarchs were men, all of whom would have been experienced riders, trained to lead their armies into battle on horseback. Even Elizabeth I was a famously good rider.

Cart or carriage travel was very uncomfortable, at least until the arrival of sprung coaches in the eighteenth century. It was also very slow and relied on the roads being in reasonable condition, which was not always the case. However, it did afford the monarch some protection from the elements.

Both the above methods of equine transport presented security problems. Much of the country was a lot more wooded than it is today, offering opportunity for attack and robbery by ill-wishers and outlaws concealed among the trees. Thus any equine travel required a large retinue for protection. This could not be avoided when the monarch needed to travel away from London, on ‘progress’ for example, where the whole court was on the move. However, the favoured transport option when the monarch wished to travel between their palaces in and around London was the row-barge. To travel by horse from Windsor to Greenwich could take days and was risky, whereas the same trip could be achieved in hours by row-barge, and was safer and more comfortable.

The Royal Bargemaster therefore became a very important member of the Royal Household, especially between the fourteenth and eighteenth centuries, so I was surprised when my early research revealed that these men had never been the subjects of a book. They have certainly been mentioned in numerous historical works, but ‘always the bridesmaid, never the bride’.

After giving almost a millennium of royal service they deserved better, and thus this book was conceived. It is hoped that the book will demonstrate their importance to the royal families across the centuries and their relevance today. Even in these modern times, a beautifully decorated vessel on a backdrop of open water is still very impressive and can be used to great effect to display the majesty of monarchy, as our current Queen demonstrated so superbly during her jubilee celebrations.

Beryl Pendley

Contemporary river appointments still in use today. Front row left to right, Watermen’s Company Bargemaster, HM Royal Waterman, HM Bargemaster and Fishmongers’ Company Bargemaster. (Picture by Reflections Photography)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Photographic images by kind permission of: The Mansion House; The Canadian Maritime Museum; Dulwich College; Julian Calder, photographer; Christopher Dodd, author; Annamarie Phelps; Malcolm Knight, ‘The Gloriana Trust’; Will Carnwath, ‘The Gloriana Trust’; N. Crouch, Reflections Photography; S. Van den Bergh, Intaglio Print; Watermen’s Co.; Vintners’ Co.; Fishmongers’ Co.; Richard Turk; W. Barry; HMB E. Hunt: MVO; HMB K. Dwan; HMB Paul Ludwig MVO; HMB C. Livett. Where not attributed, images are from public domain sources.

I

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE ROYAL BARGEMASTERS

It is not known exactly when the first Royal Bargemaster was appointed. We tend to associate the Royal Barges, and thus the Royal Bargemasters, with the River Thames, but we need to remember that the early Norman kings spent a lot of time in France, their ancestral home and power base.

The Court was also very mobile in those days, and it may not have been practical to have a defined Royal Barge and an appointed Royal Bargemaster, either in England or France. It would have been more practical to hire vessels for transport when required. We have in fact found a reference to King Edgar the Peaceable being rowed in his barge by princes on the River Dee in 973 in order to show their allegiance, but with no mention of a Bargemaster.

The Anarchy of Stephen and Matilda from 1135–54 saw the rival monarchs constantly on the move, and thus the appointment of Royal Bargemasters may not have been uppermost in their minds.

Winchester, not London, had been the capital of the Anglo-Saxon kings and was also very important to the Normans, and to a lesser degree the Plantagenet monarchs. William Rufus was buried there in 1100, and in 1207 Henry III was born there.

Richard I spent only about six months in England during the whole of his reign, preferring to spend his time either in France or on crusade, where there would have been no need for a personal Royal Barge, and was completely absent for the last five years of his life.

It is thought that King John journeyed to Runneymede in his Royal Barge in order to assent to the Magna Carta in 1215. A number of the barons who attended as witnesses to the Great Charter are also believed to have attended in their own barges. Travelling by barge rather than by road when in the Thames Valley was just as important to the great noblemen of their time as it was to the monarch.

John’s son Henry III was once caught up in a storm whilst in his barge on the Thames. The King was so frightened of the storm that he put in at the Bishop of Durham’s palace, which was the nearest suitable landing place.1

Edward I frequently travelled by barge – payments were made to his bargemaster, Fulke le Coupere, in the summer of 1297 for taking the King from Gravesend to the bridge (a kind of jetty or causeway landing) at the Palace of Westminster. He was paid to wait at the bridge until the monarch was ready to go to Rotherhithe to visit the Queen of Navarre. From Rotherhithe, le Coupere took him to the hospital beside the Tower of London, and finally back to Westminster.

Richard II set out to meet the rebels by Royal Barge during the Peasants’ Revolt in 1381.

Henry V spent much of his time in France, enough to require a Royal Barge to be sent there. On 18 June 1421, Robert Rolleston, Clerk of the King’s great wardrobe, was paid £21 14s 8d to order and provide for the reparation, amendment and preparation of a certain ‘row Barge of the said Lord the King, called Esmond del Toure, ordered to sail to France, to serve the said King in the river Seyne, or elsewhere, at the pleasure of the said King.’

Once the seat of the monarchy had been firmly established in London, the Royal Barge and thus its Master became more relevant to the day-to-day life of the monarch and the Court. Until the middle of the eighteenth century, London Bridge was the only bridge in existence in the capital, hence the reliance on travel by water.

Many factors have contributed to the role and significance of Royal Bargemaster over the centuries, including the state of the roads, the advent of modern horse-drawn carriages, new bridges being constructed over the Thames and which of the royal palaces became the primary residence of the monarchs. It should be remembered that the river was also used as a showplace, enabling the Royal Family to demonstrate their status with great waterborne pageants.

In Norman and medieval times, the roads in and around London were in very poor condition. After all, there had been no major road-building projects since the Romans left! Travel in the region was therefore slow, dirty and dangerous. Travel by Royal Barge was fast and comfortable by comparison. For example, a trip from Richmond to the Tower of London or Greenwich could be achieved in hours by water but could take days by road if conditions were difficult or the weather was bad.

Until Elizabethan times, taking journeys in wheeled transport was a less than pleasant affair. The vehicles were, at that time, slung on chains, so passengers were jolted around quite badly. This was improved somewhat by the introduction of carriages slung on heavy leather straps, and later by sprung coaches. It could also be dangerous in unsettled times.

Elizabeth I used her progresses (tours around her kingdom) as a political tool throughout her reign. In the early years of that reign she was trying to pursue a middle way in matters of religion, after succeeding her Catholic sister Mary. She needed to see and be seen, and to retain the goodwill of her people in these difficult times. Taking the Royal Barge along the Thames was the best and safest way to do this. To see and be seen in that delicate time, the Queen made two short barge trips on the Thames within a week in late April 1559. Flotillas of boats surrounded the Royal Barge, while Londoners lined the river banks to share in the music, water games and fireworks late into the night. The second celebration ended when gunpowder exploded, burning a pinnace and drowning one man. The river became a public stage that gave the Queen access to people and a smooth escape should circumstances dictate.

In Stuart times the ownership of a ‘modern’ carriage was also a great status symbol among the nobility and gentry. This eventually resulted in a proliferation of carriages for hire in the capital, to the annoyance of Charles II, who made a proclamation in 1660 to try to stem the use of hackney coaches.

Whilst these more comfortable carriages had a limited effect on the Royal Bargemaster and the Royal Watermen, it had a much more serious effect on the ordinary Thames watermen. The waterman and poet John Taylor (1578–1653) wrote:

Caroches, coaches, jades and Flanders mares

Do rob us of our shares, our wages and our fares;

Against the ground we stand and knock our heels

While all our profit runs away on wheels.

Another event which reduced the reliance of the monarch on water travel was the erecting of Westminster Bridge in 1750, followed by Blackfriars Bridge in 1769 and Battersea Bridge in 1773.

It was, however, the choice of the siting of their principal London residences that probably changed successive monarchs’ day-to-day requirement for travel on the River Thames the most. This had a considerable impact on the importance of the Royal Bargemasters, causing their role to become less and less onerous over the centuries.

From Norman times until the late Stuart period, most of the royal palaces in London and the surrounding area were built on sites adjacent to the River Thames. These include Richmond, Windsor, Hampton Court, Bridewell, Westminster, Whitehall, Bayard’s Castle, the Tower of London and Greenwich.

When Whitehall was destroyed by fire in 1698, St James’s Palace became the principal London residence of William and Mary. Notably, it does not have river frontage. George I and George II also used this palace as their primary residence, but George III considered the old Tudor palace unsuitable for his large family and in 1762 purchased Buckingham House, later to become Buckingham Palace. Again, Buckingham Palace has no river frontage.

Of course, various monarchs continued to use palaces with river frontage, such as Hampton Court, Windsor, Greenwich and later Kew Palace, but this tended to be for pleasure or as retreats from central London.

More recent monarchs have relied almost exclusively on cars and helicopters to get around London and its environs, thus no longer needing to use State Barges on a regular basis. This has left the Royal Bargemasters of the twenty-first century with, generally speaking, a purely ceremonial role. However, in recent years they have also been part of the Diamond and Silver Jubilee celebrations, adding their colourful presence to these pageants and establishing that they still have a real part to play in royal events.

II

DEVELOPMENT OF THE ROLE OF THE ROYAL BARGEMASTER

The Royal Bargemasters and indeed the Royal Watermen would have been deemed as persons loyal to the Crown, due to the fact that they would be working in such close proximity to the monarch and other members of the Royal Family. They would be responsible for keeping the monarch safe whilst travelling on the river, along with anyone whom the monarch wished to use his/her barges, such as visiting royalty or foreign ambassadors.

As the following examples will demonstrate, the Royal Bargemasters and the Royal Watermen were present at some of the most important moments in our history as well as being very close to the monarchs as they went about their daily business.

General Travel by the Monarch and Royal Family

Prior to his investiture on 27 February 1490, Prince Arthur was rowed down the Thames in the Royal Barge. He was greeted at Chelsea by the Lord Mayor of London and at Lambeth by the Spanish Ambassador.

Lady Margaret Beaufort, the mother of Henry VII, made frequent trips by barge from her London residence, Coldharbour, to Richmond, where her son lay dying in 1509.

Henry VIII sometimes used the Royal Barge purely for pleasure. In 1539, he boarded his Royal Barge at Whitehall and was rowed to Lambeth. After evensong, he continued being rowed up and down the Thames, with music playing all the while.1 When Henry was courting Katherine Howard in 1540, he was often seen being rowed to Lambeth of an evening to visit her.2

He also used his barges for pageantry. On 19 March 1541, he used the river to introduce his new Queen, Katherine Howard, to London. It was her first visit to the city as Queen. The Mayor and Livery Companies waited in their decorated barges between London Bridge and the Tower. One can only assume the tide was favourable, as the Royal Barge in which the King and Queen were travelling ‘shot the bridge’.3

When Mary I of England arrived in London with her husband Philip of Spain on 18 August 1554, they travelled by water from Richmond, landing at the Bishop of Winchester’s palace.

Elizabeth I used the Thames a great deal. In 1557, when she was still the Princess Elizabeth, she went from Somerset Place to Richmond to visit her half-sister Mary. She was taken in the Queen’s barge, which was ‘covered with a canopy of green sarsenet, wrought with branches of eglantine on embroidery, and powdered with blossoms of gold’.4 On 10 June 1561, Elizabeth I proceeded from Westminster to the Tower in the royal barges to visit the Mint, where she coined certain pieces of gold, and gave them away to those about her.5

As we have said earlier, the Royal Bargemaster and the Royal Watermen were responsible for the safety of the monarch when he/she travelled on the Thames. During Elizabeth’s reign there were various plots to assassinate her, as well as numerous rumours of such plots. On 17 July 1579, a shot was fired, injuring one of the Royal Watermen, as Elizabeth was travelling in her barge between Greenwich and Deptford. This was originally thought to be an assassination attempt, but on investigation turned out to be an accident.

On 17 July 1579, the Queen was in her ‘privie barge’ on the Thames between Greenwich and Deptford, accompanied by the French Ambassador; the Earl of Lincoln;and her Vice-Chamberlain, Sir Christopher Hatton. According to a pamphlet of the time:

[I]t chaunced that one Thomas Appletree a yong man and servant to M Henrie Carie, with ii or iii children of her Majesties Chappel, and one other named Barnard Acton, beinge in a boate on the Thames, rowing up and down betwixt the places aforenamed, the aforesaid Thomas Appeltree had a Caliver or Harquebush, which he had three or foure times, discharged with bullet, shooting at random verie rashly, who by great misfortune shot one of the watermen (being the second man next unto the bales of the said Barge, labouring with his Oare, which sate within six foot of hir highnesse) cleane through both of his armes; the blow was so great and grievous, that it moved him out of his place, and forced him to crie and scritche out piteously, supposing himself to be slaine, and saying he was shot through the body. The man bleedin abundantly, as though he had had a hundred daggers thrust into him, the Queenes Majesty shewed such noble courage as is most wonderfull to be hearde and spoken of, for beholding hym so maimed, and bleeding in suche sorte, she never bashed thereat, but shewed effectually a prudent and magnanimous heart, and most courteously comforting the poore man, she bad him be of good cheare, and sayd he should want nothing that might be for his ease, commanding him to be covered till such time as he came to the shore, til which time he lay bathing in his own bloud, which might have bene an occasion to have terrified the eies of the beholders. But such and so great was the courage and magnanimitie of our dread and soveraigne Ladie, that it never quailed.

This large, beautiful stained glass window depicting a rare image of Elizabeth I in her Royal Barge is positioned overlooking the great banqueting hall at the Mansion House in the City of London. (By help of Sir David Wotton and with permission of the Mansion House London)

Appletree was arrested, brought before the Privy Council and sentenced to death. He was sent to the Marshalsea prison, where he awaited his execution. On the appointed day, he was paraded through the city to a gibbet by the river. Appletree said, ‘I never in my lyfe intended to hurt the Queenes most excellent Majesty.’ Before the execution could take place, Sir Christopher Hatton arrived with a message announcing that the Queen had pardoned him. Later in the same month, a petition was presented to the Earl of Leicester by Thomas Appletree asking that he be freed from his imprisonment in the Marshalsea, to which he had been committed for shooting unadvisedly, to the danger of the Queen, but for which he had received Her Majesty’s pardon.6

Marshalsea Prison in Southwark.