Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Paraclete Press

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

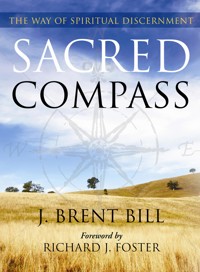

"Brent Bill has written one of the finest books on discernment and divine guidance that I have seen in a very long time." –Richard J. Foster How do you discover God's will for your life – every day? Sacred Compass offers a fresh and deeper way of living a God-directed life. J. Brent Bill draws on the quiet beauty of the Quaker path to show how spiritual discernment is more about sensing God's gracious presence than it is about making the right decisions. As you use this book to chart your own spiritual course, you will find yourself led to unexpected places, comforted by the knowledge that God uses all of our experiences to bring us close. "Sacred Compass is the perfect companion for those seeking to follow God in the way of Jesus in the midst of the realities of 21st century life. Brent Bill graciously and passionately opens the pathway of the spiritual practice of discernment for the novice and deepens the possibilities for the well experienced. This book will serve as a revelation for many and well could be the start of a revolution for a new generation Christians." –Doug Pagitt, Pastor of Solomon's Porch and Author of A Christianity Worth Believing "Sacred Compass celebrates and reassures that on this engaging, glorious, bewildering human journey, we individually and communally carry with us an ever present divine source of navigation." —Carrie Newcomer, Rounder recording artist, The Geography of Light

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 237

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2008

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE WAY OF SPIRITUAL DISCERNMENT

SACRED COMPASS

J. BRENT BILL

Foreword by

RICHARD J. FOSTER

DEDICATIONTo the Friends in Fellowship worship groupwho walked with me and guided me as I wrote this book.

Sacred Compass: The Way of Spiritual Discernment

2008 First Printing

Copyright © 2008 by J. Brent Bill

ISBN: 978-1-55725-559-4

Copyright notices for the Bible versions used in this edition are listed on the“Permissions” pages at the end of the book.

Author’s Note: The names of people in some of the stories have been changedto protect their anonymity. The stories are factual and occurred as written.None of the people are composite characters.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication DataBill, J. Brent, 1951- Sacred compass : the way of spiritual discernment / J. Brent Bill. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN-13: 978-1-55725-559-4 1. Discernment (Christian theology) 2. Spirituality. I. Title. BV4509.5.B543 2008 248.4—dc22 200800168810 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in anelectronic retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or any other—except forbrief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior written permission ofthe publisher.

Published by Paraclete PressBrewster, Massachusettswww.paracletepress.com

Printed in the United States of America

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

INTRODUCTIONTHE HOLY DISCOVERY

ONEAS WAY OPENSMoving from Tourists to Pilgrims

TWOLIVES THAT SPEAKWhat We Are Saying to Others and Ourselves Along the Way

THREEPAYING ATTENTIONSeeing the Signs on the Way

FOURTESTING OUR LEADINGSSeasons of Discernment

FIVETHE DARK PATHWhat If You Lose Your Way?

SIXWEST OF EDENWhat If the Way Takes Us to Unexpected Places?

SEVENTRAVELER’S AIDOffering Assistance to Others Along the Way

EIGHTTHE DANCE OF DISCERNMENTThe Gift and Responsibility of the Way

HIKING EQUIPMENTAdditional Resources for Following the Sacred Compass

COMPASS CALIBRATIONQuestions for Spiritual Growth

FIRE STARTERSPrayers for Pilgrims

FIRST AID SUPPLIESBooks and Web Resources for the Journey

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

PREMISSIONS

NOTES

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

FOREWORD

I DO A GOOD DEAL OF HIKING: Leisure hiking. Trail hiking. Off-trail hiking. Wilderness hiking. Overnight hiking. Extended backpack hiking. And more. One piece of equipment that is always good to have along is a compass. Especially when I am “bushwhacking” off-trail in the high country of the Colorado Rockies.

I must admit to you that I have not graduated to a G.P.S. I resist it for some reason. Yes, I know, the technology of the G.P.S. makes it a far more accurate instrument. Still, I hold back. Perhaps it’s that when I’m in the wilderness I want to be as far away from high-tech gadgetry as possible. I will even take off my watch and leave it at home.

But a compass is different somehow. A compass is an old friend. Maybe it is because the compass connects me, if only in a small way, to centuries of travelers of all kinds. Then, too, a compass guides me . . . but not perfectly. For one thing, I am always having to make the adjustments between magnetic north and true north. Also, a compass does not give me the details of a G.P.S. There are still lots of unknowns and plenty of decisions to make. I rather like that. I like the mystery. I like the unexpectedness. I like the adventure.

All of that to say that I think the metaphor of a compass is a good one when we are considering our life’s journey in relation to God. With skillful use of this metaphor, Brent Bill has written one of the finest books on discernment and Divine guidance that I have seen in a very long time.

And that is saying something. In general, I do not care for the many modern books out in the marketplace on “Divine guidance.” I wish I didn’t have to say it, but these books almost always degenerate into simplistic, rigid systems for discerning the will of God. Thankfully, Sacred Compass stands apart from these easy solutions to life’s perplexities. Its openness and flexibility is true to the realities of the frequent twists and turns of everyday life.

Brent Bill is a Quaker, and he warmly embraces this tradition. But never in a sectarian way. Most of the great spiritual insights are “loanable,” and so when Bill draws from his Quaker heritage he is doing so in the spirit of the catholicity of sharing. This is true even when he utilizes special Quaker phrases: “as way opens,” “let your life speak,” “never run ahead of your leading,” and more. He unpacks this Quaker language in such a warm and loving way that regardless of our denominational tradition we all are drawn into the reality of which the language speaks. In addition, it is clear that Bill is also engaging with a whole host of Christian traditions and showing that they all share the composite likeness of godliness.

There are many things I like about Sacred Compass. Let me mention four.

First, in his writing somehow Brent Bill is able to create “space” for us to become quiet and listen to God. The writing submerges us into prayer and allows space for the Divine/human dialogue, Spirit to spirit. It is quite amazing really. Maybe it’s the author’s openness and ease with us as readers. Perhaps it’s the naturalness and grace that gives us permission to let go of our frantic ways. Maybe it’s the freedom from strict categories of expectation and performance. For example, in a section on “Seasons of Discernment” Bill teaches about “sensing” and “waiting” and “acting.” In the teaching he reminds us that we do not, “slavishly move from Sensing to Waiting to Acting, with each having clearly defined beginnings and endings. Instead, Waiting can lead back to Sensing or forward to Action. Likewise, Action can lead back to Sensing or Waiting. Often, the three are a synthesis of each other—a blend of Sensing and Waiting while Acting, for example. They flow one to another and back around.” It is this openness and flexibility that calms my frenzied spirit. It quiets me, settles me, thickens me.

Second, Sacred Compass bravely engages the harshness and dissonance we experience in life that often punches us hard in the gut. At times even threatening to deliver a knock-out blow. (And, dear reader, if you have not yet experienced these tough realities, believe me, you will.) My two favorite chapters are “West of Eden: What if the Way Takes us to Unexpected Places?” and “The Dark Path; What if You Lose Your Way?”

“West of Eden” helps us understand that Divine guidance can, very frankly, lead to things we would never imagine or want when we started out: our own death, for example. “The Dark Path” reminds us that God is still with us when we have walked down foreign paths and gone other ways. Listen: “In the New Testament the word lost means simply that—’lost.’ It doesn’t mean being doomed or damned for all eternity. It means that whatever is lost is in the wrong place; it’s not where it should be. This is true in all of Jesus’ parables (such as the one about the lost coin) and about people, too. Things and people are lost when they are not in the right place.”

Third, Sacred Compass is eminently practical. I don’t mean “practical” in the sense of giving exercises or tasks to do. It does do that to some extent, but that is not what I am referring to. No, I mean that the whole of the book is practical. It’s the ease in approaching the subject matter. It’s the anecdotal stories. It’s the small, seemingly off-handed comments that startle us into thinking in new directions. It’s all that, and more.

And finally, Sacred Compass is filled with such encouragement. There is no grit-our-teeth earnestness here. Divine guidance is ultimately life-giving and joy-filled. In reality the “sacred compass” is simply the Holy Spirit leading us to the face of a loving God. It is Jesus, the inner Teacher, showing us how to live fully, freely. Always there is a clear expectation that this life is genuinely possible. At one point Brent Bill says that we are discovering “a fresh and deeper way of living a God-directed life—a life that eschews simple spiritual solutions and invites us into the deepest, most soulful parts of our being.” And so we are.

Richard J. Foster

INTRODUCTIONTHE HOLY DISCOVERY

A COMPASS, no matter what direction we turn, always points us to the north pole—a destination most of us (unless we’re named Amundsen, Byrd, Peary, or Henson) will never reach in this lifetime. In that way, a compass makes a good metaphor for our spiritual lives and the work of discerning God’s will for us.

Many times I wish God spoke as clearly and as obviously as Mapquest or Google Maps or a GPS. But God doesn’t. Maybe that’s because we don’t navigate the life of faith via anything remotely resembling a GPS. Instead, the divine compass points us to our spiritual true north—the mind and love of God. Our sacred compass operates in our souls and calls us to life with God—life abundant and adventurous, even when we wish living was less of an adventure. The sacred compass leads us on a life of pilgrimage—a hike to wholeness and holiness.

In pointing us always to God, the compass helps us with our soul’s deepest question, What am I supposed to do with my life? The question of how to live our lives especially presses on those of us who sense we are not merely humans trying to be spiritual, but are deeply spiritual beings endeavoring to live as fully human.

Every day begins with that “what” question. We wake up each morning with a cavalcade of choices before us—beginning with whether or not to get up. Things get more complicated from there. The very act of making a choice—any choice—shows us that our lives are more than our own. We belong to ourselves, but we also belong to others—our family, our neighbors, our pets, our coworkers. Most of all, we belong to God.

When I was in college, I encountered a group handing out little buff-colored booklets titled “The Four Spiritual Laws.” The first spiritual law was, “God loves you and has a wonderful plan for your life.” The idea that God has a plan for us is not a novel concept. The Bible and the whole of Christian history are full of examples of people seeking to determine God’s will. In order to find God’s will, women and men of faith cast lots, set out fleeces, prayed, fasted, learned to listen to donkeys, went on retreats, climbed up cacti, and more. These days, bookstores are crammed full of titles about learning God’s will. Amazon.com alone offers more 38,000 books on the subject. While some of those books offer you five easy steps for discerning God’s direction for you, this book is not one of them. Uncovering God’s direction for us is not the five-easy-steps kind of simple.

Discovering spiritual direction is simple—but in an amazingly countercultural and counterintuitive way. It is about heeding the Holy Spirit. Learning to follow the divine compass means stopping and paying attention instead of looking for a magical map with the shortest route highlighted in yellow. Learning what God wants of us means letting the Holy Spirit guide us into the deep places of our souls. We learn to look for God in those deep places and in all the places our lives take us.

When we travel through life attentive to the sacred compass, we find that God’s direction changes us. We discover that spiritual discernment is about sensing the presence and call of God, and not just about making decisions. The process of following the sacred compass awakens us to a life of constant renewal of our hearts, minds, wills, and souls.

This renewal moves us deep into personal spiritual transformation. And as we change, we also change the lives of the people around us and, ultimately, the world. Such transformation is not accomplished by following a pre-published route mapped out in The God’s Will Guidebook. Rather, true transformation happens when we let the map (and any idea of a map) flutter from our tight grasp and instead begin to use the sacred compass that God provides—the compass of the Holy Spirit’s work within us.

THE SACRED COMPASS SHOWS US GOD’S DIRECTION

That inner compass tells us that we can know God’s direction for us. I picked the seminary I attended partly because of its motto—“We hold that Christ’s will can be known and obeyed.” I found the thought that I could know God’s will called to my heart, and I don’t think my heart is the only one that hears that call. When I surveyed some of my friends and readers, I found that almost 90 percent of them said that there was a time in their lives when they knew what God wanted them to do. Some of their experiences appear in this book. Their experiences of God’s direction were as varied as the people I surveyed. While their God-encounters were unique, there were some similarities. Each of them said:

they found it daunting to say that God led them

their experience of divine direction was unmistakable

their experience pointed them to God

they were led to act

Writer Amy Frykholm’s experience illustrates these aspects of God-encounter:

I’m very hesitant to say that “God wanted me to do something,” and yet I have experienced times of extraordinary clarity when not only the direction that I should take seemed clear, but the workings of something beyond myself, the softening up of my whole self in order to accept a previously unacceptable direction, took place.

The most obvious example is a period when, after six years of graduate school, I abandoned the path clearly laid out for me toward an academic job and an academic life. Instead, after a long period of discernment that included long conversations and long silences, a lot of tears, a lot of giving up of ego, it became clear to me that another, less logical path, was the better one.

One of my guides during this time was the Sufi poet Hafez, and especially his poem, “Some fill with each good rain,” and the lines: “There are different wells within your heart. Some fill with each good rain, Others are far too deep for that. In one well You have just a few precious cups of water, That ‘love’ is literally something of yourself, It can grow as slow as a diamond If it is lost.”

The path that I was on seemed determined to deplete those few cups of water, and I knew, with some deep part of myself, that I would need to find another path if I wanted to be renewed.

THE SACRED COMPASS LEADS US TO HOLY DISCOVERY

Following our sacred compass leads us to a place where we learn from God in the daily and in the lifelong. This place is one of seeking and sensing God. It is a place of divine direction and spiritual opportunity. Learning to follow the sacred compass means living in a constant state of discernment and obedience to God.

The divine compass asks us to travel by faith and put to use the various maps we’ve been given—maps such as the Bible, prayer, spiritual friends, and other faith practices. Our compass takes us to a fresh and deeper way of living a God-directed life—a life that eschews simple spiritual solutions and invites us into the deepest, most soulful parts of our being.

Keeping our soul’s eyes on the sacred compass leads us to the holy discovery that we can move through life with purpose and promise, even in those times when we may not sense with certainty what that purpose and promise are.

THE SACRED COMPASS COMPLEMENTS OUR UNIQUENESS

The sacred compass also shows us that the path of discernment is unique to each person. None of us follows the exact same paths as any other person. None of us has the exact same talents—or failings—as any other person. And God does not use us in the exact same way as any other person. There was only one Moses raised in Pharaoh’s court, one Mary the mother of Jesus, one Martin Luther, one Julian of Norwich, and one you.

The sacred compass leads each of us to the life only we can live. Our compass calls us to use the gifts only we can give. In a grace-filled way, our compass invites us into a life of continuous experiences of God and of spiritual transformation. As we move toward divine guidance, we joyfully behold the face of a loving God gazing back at us.

ONEAS WAY OPENS

Moving from Tourists to Pilgrims

WILL YOU BE COMING FOR DINNER TOMORROW?” one might ask. “I will, if way opens,” a Quaker is likely to respond. Quakers, also known as Friends, have been known to drop “as way opens” into conversation as easily as other folks do “Hello” or “How’re you doing?” It’s almost become a cliché.

Yet, in spite of its colloquial use, we most often hear that phrase during deep discussions around important decisions. This saying speaks to the belief that God’s revelation, even in daily life, continues for all who follow their sacred compass. God works within and around us, leading, guiding, and opening the way, sometimes when we least expect or feel it. The idea of being led and guided implies movement. If we’re being led or guided then we must be being led or guided somewhere. The sacred compass shows us that we are on a pilgrimage to our spiritual true north—God.

As way opens implies a deep way of developing our spiritual insight, making major decisions, and planning. It is the condensed version of a longer phrase: “to proceed as way opens.” There’s that movement again—but it is movement with a cautionary note. Proceed, yes, but only as way opens.

Counter to our lives of action, the sacred compass tells us to take time to wait for God’s guidance before moving ahead. Part of following way opening is learning to be less hasty—to take time to let the direction needle stop wobbling and point its way to God.

AS WAY OPENS IS A PILGRIMAGE

Way opening teaches us that the compass is about more than decision making. While we use its principles and tools to help make major life decisions—careers, life partners—and minor ones, a primary teaching of way opening is to base our movement on God’s timing. Decisions big and small are portions of our life of pilgrimage, but they are not the destination. Life with God is the destination.

Whom we marry or don’t, where we live or won’t, certainly factor into our life’s path. They influence its direction, but our journey continues no matter what decisions we make. That’s why we need to learn to see God at work within and around us. When we behold God present with us, we find that our lives are lives of pilgrimage and not of static spiritual sitting.

PILGRIMS LEARN FROM OTHER PILGRIMS

Growing up, my religious training was steeped in the Bible. Of particular interest to me, as a kid, were the stories of children in the Bible. One of my favorites was the story of Samuel. He was a boy in a time when (as the King James Version puts it) “the word of the LORD was precious in those days; there was no open vision.” Precious and open himself, Samuel heard God’s voice, obeyed it, and came to be known as “a prophet of the Lord.”

The idea that God could speak to a kid was pretty heady. Samuel’s story taught us to listen to God and for God. Mrs. Clark, our Sunday school teacher, assured us that if we did listen, and if we heard God’s voice and obeyed it, we would also be known for opening the vision of God and making God’s word precious.

The Bible is filled with examples of people—young and not-so-young—who sought God’s will. The early disciples looked for direction in replacing Judas. Joshua asked God about apportioning the land of Canaan to the people of Israel. Jesus, too, was an example of seeking God’s will: while praying in the Garden prior to his passion, he sought confirmation of God’s path for him: “And [Jesus] withdrew from them about a stone’s throw, and knelt down and prayed, ‘Father, if thou art willing, remove this cup from me; nevertheless not my will, but thine, be done.’” Jesus’ path led to the cross, the grave, and ultimately, resurrection. For Jesus, the way opened into our forgiveness and our healing.

Christian church history is also replete with stories of women and men in quest of God’s direction for their lives. These range from the desert fathers to Thomas à Kempis to Mother Teresa to the person who sits next to me in the pew each Sunday morning.

One of my favorite stories is that of St. Ignatius. Born in Spain in the early fifteenth century, the young Ignatius was no model of sainthood. Ignatius was pompous and obsessed with desire to win glory on the battlefield. Rejecting his father’s wish for him to become a priest, Ignatius went on military adventures. During one battle, a cannon ball shattered his leg. While recovering in Loyola, he asked for books about romance and chivalry. Instead, he received books on the love of Christ and the lives of the saints. While reading, he discovered that his old dreams of romance and adventure left him unsettled and unhappy. The saints, in contrast, seemed serene even in horrible circumstances. With a shift of spirit, he felt called to a higher life of devotion to God and later wrote Spiritual Exercises. Now considered a spiritual classic, his book uses a four-week, systematic review of our personal spiritual lives to train the soul. They are considered a pilates for piety.

Ignatius’s idea of “soul conditioning” or “spiritual sit-ups” was not original. St. Paul hinted at that idea 1,400 years earlier, when he wrote to Timothy, “train yourself to be godly. For physical training is of some value, but godliness has value for all things.” With this training in mind, Ignatius took Paul’s concept and turned it into a set of spiritual exercises that are still used to great effect today.

Recently, pastor and author Rick Warren has generated a new form of contemporary spiritual exercise around the themes of the purpose-driven life and forty days of purpose—all based on the tenet that a “healthy, balanced church helps develop changed lives—people who are driven by the five biblical purposes that God designed for every human life.” According to Warren, the five purposes for our lives are worship, fellowship, discipleship, ministry, and missions. Millions of copies of his book The Purpose-Driven Life have been sold and thousands of churches have participated in a forty days of purpose campaign.

Men and women who find them helpful to their spiritual walk eagerly read books by Ignatius, Warren, and other spiritual explorers. We want to learn from others who have trod the pilgrim path. Their words enlighten, embolden, and beckon us onward. We often feel like we’re on our journey alone. Writings of fellow pilgrims remind us that, while our way is unique to us, there are many, ancient and modern, who have traveled with us. I’ve traveled with Ignatius, Thomas Kelly, Anne Lamott, and a host of others. How about you? Who would make your list of fellow pilgrims? Whose writing do you read for companionship on the way?

PILGRIMS ARE LED BY THE HOLY SPIRIT

The concept of as way opens takes a different tack from either Ignatius or Warren. Instead of focusing on four-week spiritual exercises or forty-day programs, as way opens points us to the constant presence of the Holy Spirit in our lives. The Holy Spirit is our sacred compass; its role is to show us our way. Jesus said:

If you love me, you will keep my commandments. And I will pray the Father, and he will give you another Counselor, to be with you for ever, even the Spirit of truth, whom the world cannot receive, because it neither sees him nor knows him; you know him, for he dwells with you, and will be in you.

This Gospel passage reminds us that God is with us on our pilgrimage—the indwelling Paraclete (a Greek word that is sometimes translated as “counselor”) accompanies us. God gives us the Paraclete to guide us into God’s truth. The Holy Spirit fulfills Christ’s promise that God will be with us forever as it works in our souls, teaching and guiding us. As way opens is about learning to pay attention to this Inner Teacher, our sacred compass. When we do so, we see God’s direction for our questions big and small, immediate and lifelong. We sense, through the work of the Paraclete, that God is always present with us, guiding and directing our lives. We witness the work of our personal sacred compass.

The early Friends believed that the Inner Teacher spoke with a quiet voice heard in the soul, so they worshiped in silence. They sought souls still enough to hear the God who speaks in sacred silence. They weren’t the first to hear God’s voice in soulful stillness. After God directed the prophet Elijah to go stand on a mountain, he discovered that God was not in the earthquake, wind, or fire, but in the sound of “sheer silence”:

“Go out and stand on the mountain before the LORD, for the LORD is about to pass by.” Now there was a great wind, so strong that it was splitting mountains and breaking rocks in pieces before the LORD, but the LORD was not in the wind; and after the wind an earthquake, but the LORD was not in the earthquake; and after the earthquake a fire, but the LORD was not in the fire; and after the fire a sound of sheer silence. When Elijah heard it, he wrapped his face in his mantle and went out and stood at the entrance of the cave.

God’s voice is at times so deep and so holy that it may appear to be nothing but silence—unless, like Elijah, we pay heartfelt attention. Can you think of a time when you heard God in the stillness of your soul? How did you get to that place of quietness and listening? When we quiet our soul’s busy-ness, we hear the voice of the Inner Teacher showing us the way opening.

PILGRIMS CAN TAKE MANY PATHS

I grew up evangelical Quaker. We subscribed to the belief that “God loves you and has a wonderful plan for your life.” As such, we spent a lot of time, especially as teenagers, trying to determine what this plan was, especially about things such as where to go to college, whom to marry, and what career to go into.

Some of these decisions were easy—our church had already discerned some of God’s direction for our lives. In our case, the plan did not include smoking cigarettes, drinking alcohol, cursing, or dancing. If we went to college, we’d go to one of our church-affiliated schools. There were jobs we should take and others we couldn’t. Bartending was out of the question. Many careers had carefully delineated gender roles. Young men could be pastors; young women could be pastor’s wives. When we got married, we’d marry someone from our brand of Christianity, preferably someone from our local church. All of these guidelines were set up so that we could faithfully keep the first spiritual law and follow that wonderful plan God had for our lives.

And therein lies the rub—“a wonderful plan for your life.” A. One plan. Notice I didn’t say wonderful plans for your life. The implication was that God had just one plan, which also implied that you’d best spend a lot of time making sure you knew what that plan was so you didn’t mess it up.