Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

The powerful German battlecruiser Scharnhorst was stalked and engaged on 26 December 1943 by a superior Allied naval task force off the North Cape of Norway. In pitch darkness and mountainous seas, British warships, led by HMS Duke of York and HMS Belfast, engaged the Scharnhorst in a clash of the titans that saw the pride of the German Navy sent to the bottom of the Barents Sea. Of the 1,972 men on board, only 36 were saved. It was the last battle to be fought in the Atlantic between capital ships. In 2000, the Norwegian writer and investigative journalist Alf R. Jacobsen led the expedition that found and filmed the wreck of the Scharnhorst, 300 metres down in the freezing ocean inside the Arctic Circle. In Scharnhorst, he brings together the compelling story of this important naval engagement and his personal account of how he finally succeeded in locating and filming the wreck of the ill-fated battlecruiser.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 593

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

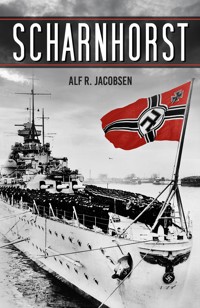

Front cover image: Scharnhorst. (Naval Historical Foundation NH97536)

First published in Norwegian as Scharnhorst in 2001 by H. Aschehoug & Co. (W. Nygaard), Oslo

First published in English in 2003 by Sutton Publishing

This paperback edition first published 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Alf R. Jacobsen, 2001, 2003, 2024

English translation © The History Press, 2003, 2024

Translated from the Norwegian by J. Basil Cowlishaw

The right of Alf R. Jacobsen to be identified as the Authorof this work has been asserted in accordance with theCopyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprintedor reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic,mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented,including photocopying and recording, or in any informationstorage or retrieval system, without the permission in writingfrom the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 722 3

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Foreword

Part I

1. Death off the North Cape

2. An Unsuccessful Attempt

3. A Time for Dreams

Part II

4. Operation Ostfront

5. The Mystery Deepens

6. Empty Days

7. London Comes to Life

8. Off Bear Island

9. Operation Venus

10. An Unexpected Catch

11. Alarums and Excursions

12. Further Setbacks

Part III

13. Studied Indifference

14. The Mystery of the Logbook

15. Admiral Fraser’s Plan

16. The Dream of Oil

17. The Report from U-601

Part IV

18. The Naval College Simulator

19. The Scharnhorst Puts to Sea

20. ‘I have confidence in your will to fight’

21. What Was in the Mind of Konter-Admiral Bey?

22. Defeat

23. Found!

Part V

24. The Intelligence Riddle

25. Aftermath

26. The Reckoning

Appendix: Table of Equivalent Ranks

Notes

Bibliography

FOREWORD

I grew up in the shadow of the Second World War. Admittedly, when I was born – in February 1950 in Hammerfest, the world’s northernmost town, not far to the west of the North Cape – the war had been over for nearly five years. But at that time the town had still not been rebuilt after its devastation in the autumn of 1944, and both my parents were still marked by their experiences during five years of war.

Norway was occupied by Nazi Germany in the summer of 1940, the first enemy soldiers making their appearance in Hammerfest in August of that year. They were soon followed by many more, as the town was an important staging-post for the forces being assembled for a joint German-Finnish attack launched on the ice-free port of Murmansk in June 1941, making it an important though little-known sector of the Eastern front.

The first years of occupation were peaceful. Hammerfest was a small town of barely four thousand inhabitants, so the presence of large numbers of enemy troops and naval units demanded a good deal of forbearance and give-and-take on both sides. After a time facilities were improved and the town turned into a supply base. To this end, as early as the autumn of 1940 a large refrigerator ship, the Hamburg, was anchored in the harbour. The ship’s owners purchased large quantities of Norwegian-caught fish, which were processed and frozen on board. Shortly afterwards a Cuxhaven company, Heinz Lohmann & Co. AG, set up a permanent fish-processing factory in the town, not far from my childhood home. Although the fish was mostly processed by four hundred female workers brought in from the Ukraine, many Norwegians also found employment at the Lohmann factory. One of them was my father, who started work there in 1941. At one time a whole floor of our house was requisitioned as living quarters for two of the factory’s managers.

The German presence was further reinforced in January 1943 when Hammerfest became the front-line base of two U-boat flotillas, nos 13 and 14, which operated against convoys carrying supplies through the Barents Sea to Russia. U-boot-Stützpunkt Hammerfest was the Black Watch, a 5,000-ton passenger liner which the Germans had commandeered and on board which U-boat crews were given an opportunity to rest and relax after their long and arduous patrols in the Arctic Ocean; it was backed by a cargo ship, the Admiral Carl Hering, which provided workshop facilities and kept the U-boats supplied with torpedoes and ammunition. The Black Watch was moored behind anti-submarine nets close to the Lohmann wharf and was thus clearly visible from my parents’ home.

The end came in the autumn of 1944 when Finland concluded a separate peace with the Soviet Union. Soviet troops broke through the Litza front on the Kola peninsula, which for three years had been the scene of a bloody and more or less static war of position. Forced to establish a new line of defence east of Tromsø, the mountain troops of 20. Gebirgsarmee made a rapid retreat. To prevent the Russians from following close on their heels, Hitler ordered their commander, Generaloberst Lothar Rendulic, to adopt the same ruthless scorched-earth policy that had been used to such terrible effect in the Soviet Union. In northern Norway the consequences were disastrous, with more than fifty thousand people being forcibly evacuated to regions further south. Every building, along with the infrastructure, was destroyed, being either burned or blown up, and the harbours were mined. By the time the retreat came to an end in February 1945, an area the size of Denmark had been razed. The only building left standing in Hammerfest was the small sepulchral chapel. My mother, father, brother and two sisters were evacuated towards the end of October 1944. All they were able to take with them were two small suitcases; everything else was consumed by the flames.

I grew up in the 1950s, when Hammerfest was still being rebuilt as a centre of Norway’s modern fishing and tourism industries. As children, I and my friends played in the ruins of the Lohmann factory, in the demolished bunkers and in what was left of U-boot-Stützpunkt Hammerfest. In the long winter evenings I often heard my mother talk about the many dramatic events of the war. She described what it had been like when the Russians and British bombed the German installations and when a German troopship, the Blenheim, was torpedoed just outside the approach to the harbour with heavy loss of life. She had seen both the Tirpitz and the Scharnhorst glide past, shadowy shapes against the mountains to the south.

As a writer and chief editor in the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation’s Television Documentary Department, I set out in the spring of 1999 to search for the wreck of the German battlecruiser Scharnhorst, but it was not just with the intention of recreating the Battle of the North Cape, which was fought on St Stephen’s Day, 26 December 1943. I also felt an urgent need to acquire a deeper understanding of the events that had made the islands and fjords around Hammerfest and Alta into northern Europe’s largest naval base – and had so strongly affected the lives of my own family.

I discovered that many good books had been written about the battle, but they were all based on either British or German sources. My advantage was that I would probably be the first person in a position to draw upon declassified files and other sources in all the countries involved in the chain of events that concluded with the tragic loss of the Scharnhorst, namely Great Britain, Germany and Norway, as well as, to a lesser extent, the United States and Russia.

The Battle of the North Cape reached its climax after four action-packed days, starting from the moment convoy JW55B was discovered by a German aircraft in the Norwegian Sea at about eleven in the morning of Wednesday 22 December 1943; the Scharnhorst was sent to the bottom 66 nautical miles north-east of the North Cape at quarter to eight on the evening of Sunday 26 December. On the German side, in addition to the Scharnhorst herself and her five escorting destroyers of the 4th Destroyer Flotilla, also engaged were various reconnaissance aircraft and eight U-boats operating from bases in Narvik and Hammerfest. On the basis of war diaries, reports, letters and interviews with survivors, I have endeavoured to cover every facet of the action – to convey something of what it was like for the men battling against wind and wave in the U-boats and surface vessels, for those carrying out lonely reconnaissance flights above the endless expanse of storm-lashed ocean and for those who waited at home, on both sides of the front line. It is the first time such a comprehensive approach has been adopted. I have also tried to put together the first complete picture of the intelligence obtained, both through Enigma decrypts and through the work of the agents in the field. Aided by the new insights afforded into the Scharnhorst’s last moments by our film of her mangled hulk on the sea floor, I hope that I have succeeded in recounting the story of the German Navy in northern Norway and the Battle of the North Cape as accurately and realistically as possible. This book is about one of the greatest naval battles ever fought. But it is first of all a book about the people involved.

Many people are entitled to a share of the credit for locating, after much hard work and many frustrating attempts, the wreck of the German battlecruiser in the autumn of the year 2000. They all helped to make this book possible and all are mentioned by name, either in the text or in the notes.

I should like at this point to express my thanks to Bordkameradschaft Scharnhorst, in the person of the association’s president, Wolfgang Kube, as well as to the survivors of the ship’s sinking and the next-of-kin of the men who were lost, all of whom, in the course of countless long conversations, so freely shared their memories with me. I am especially indebted to Mrs Gertrud Bornmann and Mrs Sigrid Rasmussen, who lost their loved ones in 1943 and 1944 respectively, and who opened their lives to me. I should also like to express my gratitude to the surviving members of U-716 and other German U-boats who took part in the long, drawn-out and arduous submarine war in the Arctic and who so patiently answered my many questions. The same applies to the British and Norwegian officers and men of the Allied fleet which finally surrounded and defeated the Scharnhorst in the fury and darkness of winter off the North Cape.

Allow me also to thank the British television producer Norman Fenton. Over the years he and I spent a great deal of time together in the Barents Sea, from the time we began to search for (and found) the wreck of the British trawler Gaul, right up to the time when we did the same with the Scharnhorst. It is doubtful whether we would have succeeded had it not been for Norman’s experience and unflagging enthusiasm.

At the Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv in Freiburg I was greatly helped by Helmut Döringhoff, who on our many visits led us to the documents we sought. The same applies to Jürgen Schlemm, a specialist on the U-boat war, who works in close collaboration with Das U-boot-Archiv in Cuxhaven and the amazing website uboat.net, and who so generously shared his expertise with me. I also wish to thank my Norwegian editor, Harald Engelstad, for his advice and encouragement in the writing of this book, and my translator, Basil Cowlishaw, who, thanks to his experience as a wireless operator in the wartime Royal Air Force and wide knowledge of the course of the Second World War, made this English-language edition possible. My wife Tove Thorsen Roev, an artist, is responsible for the maps and has been my adviser and, as always, my greatest source of inspiration throughout.

Alf R. Jacobsen

Oslo, Norway

March 2003

I

CHAPTER ONE

DEATH OFF THE NORTH CAPE

THE BARENTS SEA, 19.30, SUNDAY 26 DECEMBER 1943

By this time the starboard side of the ship was already under water. Stoker Helmut Feifer slipped and slithered down the sloping deck until brought up short by an anti-aircraft gun, to which, by a superhuman effort, he managed to cling. He felt an urgent need to pray, but couldn’t find the words. The front of his shirt was soaked in blood. He gagged at every breath he took, overcome by the acrid stench of cordite fumes and burning oil. A south-westerly gale had raged all night and throughout the dying day. Battered and bruised, he ached in every joint. His ears were still filled with the cries of the wounded, of the many of his shipmates who had had to be abandoned in passages and sickbays. All about him towered the black waves. The wind, ice-cold, relentless, set him shivering uncontrollably.

Utterly exhausted and in a state of shock as I was, I was tempted to give up. I mentally bade farewell to my mother and father and prepared to die. Then one of my shipmates struggled past and roused me from my stupor. He grabbed hold of me and heaved me out on to the deck. I remained clinging to the gun-mounting until the next wave broke in over the rail. At that moment I released my grip and allowed myself to be swept overboard by the torrent of water, away from the sinking ship.

By then the Scharnhorst’s death throes had lasted for nearly three hours – since 16.47, when the Duke of York and the Belfast had fired the first of their star-shells. The end could not be long delayed.

The sea was still running high, despite the deadening effect of a thick covering of oil. It was pitch dark. I shouted and shouted, but no one answered. As my body began to grow numb and stiff with cold, it was brought home to me that, unless a miracle occurred, I didn’t have long to live. Suddenly, from the crest of a wave, I saw a life-raft drifting past. I swam towards it. When I crawled aboard, almost at the end of my tether, I heard a voice say, ‘He’s wounded, he’s covered in blood.’ I felt a stab of fear. I was afraid they’d throw me back into the sea. I was only twenty and I didn’t want to die, so I gasped that it wasn’t my blood, it was my friend’s.

Feifer was telling the truth. Earlier that evening he had been sitting deep within the bowels of the ship, playing his mouth-organ. Every time the battlecruiser’s heavy guns thundered out the whole ship shuddered. But Feifer wasn’t worried. He continued to play, one tune following another: Lili Marlen, Muss I denn, Du schwarze Zigeuner – carefree, romantic ballads calculated to sustain his shipmates’ dreams and yearnings for home. To Feifer, and hundreds of other young sailors like him, the Scharnhorst was the ship that couldn’t sink – a floating city, an unassailable fortress and the pride of Hitler’s Germany. The twenty-one watertight bulkheads were encased in Krupp steel that was in some places 32 centimetres thick. The turbines were capable of developing more than 160,000 horsepower, giving the battlecruiser a maximum speed of 32 knots – faster than any comparable naval vessel in the world. Many people considered the Scharnhorst the most graceful warship ever built. To the ship’s company and countless other admirers she was, quite simply, invincible. ‘I was absolutely convinced that she was unsinkable. I was never the least anxious on that score. I was sure we’d all return home unscathed,’ says Feifer.

Even the experienced staff of the British Naval Intelligence Service who interrogated the survivors after the battle remarked on this unshakeable belief.

Contrary to expectations, the survivors, all of whom were ratings, presented a front of tough, courteous security-consciousness and evidence of high morale … Scharnhorst seems to have occupied in the affections of the German public a position analogous to that occupied by HMS Hood in England before she was sunk. A certain legend had grown up that she was a ‘lucky ship’ and her men considered themselves the pick of the German Surface Navy and a cut above all their rivals.

It was not until a shell from one of the battleship Duke of York’s heavy 14-inch guns penetrated the ’tween deck and burst in the Scharnhorst’s number one boiler room that Feifer realized the gravity of the situation. ‘All my shipmates were killed instantly – with one exception. He was sitting up against the bulkhead. His clothes caught fire and his hair burst into flame, like a torch. I can’t describe how he suffered. I helped to carry him up into C turret and from there to a first-aid station. It was his blood that had stained my shirt.’

In just under three hours the thirteen Allied vessels surrounding the Scharnhorst fired more than 2,000 shells and 55 torpedoes at her. By about 19.30 on 26 December 1943 the once-proud battlecruiser had been reduced to a blazing, shattered hulk and was totally defenceless. Some decks looked like abattoirs. The Interrogation Report says: ‘Survivors described frightful scenes of carnage in some of these compartments, with mangled bodies swilling around in a mixture of blood and sea water while stretcher parties picked their way through the damage with ever-increasing numbers of wounded.’

Despite the destruction, evacuation continued in an orderly fashion until the order came to abandon ship. Ernst Reimann, an artificer from Dresden, was responsible for the hydraulics of the after triple turret. Together with the rest of the gunners, he put on his life-jacket. ‘We carried on firing until we ran out of ammunition. The command was then given to load the last shell. We fired, then shut down all the machinery and closed off the hoist leading from the magazine. The list to starboard continued to increase, but we waited calmly. When the order came to abandon ship, one by one we made our way out through the hatch. From there it was only a 10-metre drop into the sea.’

Because of the increasing list, nineteen-year-old signaller Helmut Backhaus from Dortmund was finding it hard to keep his balance on his perch on the observation platform, 38 metres above the deck. He came from a line of Ruhr miners and as a boy had never had anything to do with the sea. His stepfather had been furious when Helmut sought his permission to join the navy, and had refused to give it. But Helmut was not one to take no for an answer. At the age of seventeen he ran away from home and joined the German Kriegsmarine. He had been on board when the Scharnhorst, accompanied by the Gneisenau and Prinz Eugen, made her celebrated dash through the English Channel from Brest to the Elbe, and had witnessed attacking British aircraft being shot out of the sky one after another.

Now the boot was on the other foot. The blackness of the night was constantly lit up by the flames belching forth from the muzzles of countless heavy guns. The enemy ships seemed to be everywhere. There was no escape; all that remained was the raging, ice-cold sea beneath him.

The phone rang. It was an artificer friend from my home district. ‘Promise me you’ll be honest,’ he said. ‘How serious is it?’ I told him to drop everything and prepare to abandon ship. ‘You must be mad,’ was his reply. He wasn’t aware that the Scharnhorst was sinking. I tore off my fur-lined jacket and boots and clambered over the bulwark. By the time I got to the enormous searchlight I was already knee-deep in water. A breaking wave lifted me up. I kicked out. I had to get clear, to avoid being sucked down by the sinking ship.

Some distance below where Backhaus had been stationed, on the bridge, where the storm lights had been staved in and the instruments destroyed by shellfire, Petty Officer Wilhelm Gödde heard the Captain issue his last orders:

‘All hands on deck! Put on life-jackets! Prepare to jump overboard!’ Most of us refused to leave the bridge without the Captain and Admiral Bey. One young seaman said quietly, ‘We’re staying with you.’ The two officers managed to make us leave, one by one. On the deck, all was calm and orderly. There was hardly any shouting. I saw the way the First Officer helped hundreds of men to climb over the rails. The Captain checked our life-jackets once again before he and the Admiral took leave of each other with a handshake. They said to us, ‘If any of you get out of this alive, say hello to the folks back home and tell them that we all did our duty to the last.’

Others elected to remain on board. When Günther Sträter left the after 15-centimetre battery, the deck was strewn with dead and wounded. ‘One of the chief petty officers, Oberstockmeister Wibbelhof, and his Number Two, Moritz, refused to leave their post. “I’m staying here, where I belong,” Wibbelhof said. When we left the turret, he shouted after us: “Long live Germany! Long live the Führer!” We answered in similar vein. Then he sat down and calmly lit a cigarette.’

The time was now 19.32. Racing in from the north-west came three British destroyers, Virago, Opportune and Musketeer, heading straight for the doomed giant. At a range of 2,000 metres they fired a total of nineteen torpedoes. These were followed by three more from the cruiser Jamaica. Many scored hits, causing the Scharnhorst to increase her list to starboard.

A strong gale was still blowing from the south-west, but close to the ships the oil-covered sea was strangely calm. Helmut Backhaus was a strong swimmer. ‘I stopped and turned in the water to get my bearings. It was then that I saw the keel and propellers. She had capsized and was going down bow first. Immediately afterwards there were two violent explosions. It was like an earthquake. The ocean heaved and shuddered.’

To Helmut Feifer, clinging to his life-raft, the hull loomed up in front of him like a black shadow. ‘I thought, “Mensch! [Man] We’ve taken one of the British down with us.” Even then I hadn’t grasped that it was the Scharnhorst. I thought it was another ship going down – one we had sunk.’

Some distance away Wilhelm Gödde, who was still in the water, could see straight into the Scharnhorst’s funnel, which was lying half-submerged. ‘It was like looking into a dark tunnel,’ he said. The last he heard before the ship rolled over and disappeared beneath the surface of the sea was the sound of the turbines. ‘It was a terrible sight, lit up as it was by star-shell and the ghostly white beams of the destroyers’ searchlights. Where the searchlights struck the black and blue of the sea, the crests of the waves glittered and gleamed like silver.’

Nineteen-year-old Ordinary Seaman Helmut Boekhoff clung to a wooden grating as he desperately fought to paddle away from the danger area. ‘In the light of a star-shell I could see her three propellers still turning. Suddenly she disappeared from sight, only to reappear a moment later. When she went down for a second time, it was for good. I felt the violence of the shock wave as it struck my legs and abdomen; deep down, something had exploded.’

Among those present, the only ones not to see the Scharnhorst go down were the men who had vanquished her. When the Jamaica completed her torpedo attack at 19.37, the battlecruiser’s secondary guns were still firing at irregular intervals. Ten minutes later the Belfast closed in at high speed to deliver the coup de grâce – but by then all that was left was floating wreckage.

‘All that could be seen of Scharnhorst was a dull glow through a dense cloud of smoke which the star-shells and searchlights of the surrounding ships could not penetrate. No ship therefore saw the enemy sink, but it seems fairly certain that she sank after a heavy underwater explosion which was heard and felt in several ships about 19.45,’ wrote Admiral Bruce Fraser after the engagement.

At the time, however, the situation was far more confused than would appear from the Admiral’s report. At 19.51 Fraser signalled all ships to leave the area, ‘… EXCEPT FOR SHIP WITH TORPEDOES AND DESTROYER WITH SEARCHLIGHT’. While Fraser impatiently paced backwards and forwards on the flagship’s bridge, the destroyer Scorpion picked up thirty survivors; another destroyer rescued a further six. Some twenty minutes later, at 20.16, Fraser was still not certain of how things stood. Accordingly, he wirelessed the Scorpion, ‘PLEASE CONFIRMSCHARNHORSTIS SUNK.’ It was not until 20.30 that the Scorpion replied, ‘SURVIVORS STATESCHARNHORSTHAS SUNK.’ Five minutes later, at 20.35, Fraser signalled the Admiralty in London, ‘ SCHARNHORSTSUNK.’ An hour later the Admiralty replied, ‘GRAND. WELL DONE.’ Shortly afterwards Fraser gave the order to call off the action and headed at full speed for Murmansk.

Several hundred of those on board went down with the Scharnhorst, but a large number – perhaps more than one thousand officers and young ratings – were left to die in the open sea, buffeted by wind and wave. All in all, the German Kriegsmarine lost 1,936 men off the North Cape that fateful evening in December. As the German broadcasting service proclaimed a few days later, they ‘died a seaman’s death in a heroic battle against a superior enemy. The Scharnhorst now rests on the field of honour.’

The Battle of the North Cape constituted a turning point in the war in the north. Never again was the German High Seas Fleet a direct threat to the Murmansk convoys. In the event, Hitler’s capital ships were to remain inoperative for the rest of the war, while in the Atlantic gunfire was never again to be exchanged between armoured giants of the magnitude of the Duke of York and Scharnhorst. The era of the battleship was at an end. The Battle of the North Cape brought to a conclusion a process of development that had lasted for a century. When the guns fell silent off the North Cape, a naval epoch came to a close.

Admiral Bruce Fraser delivered his final ‘Despatch’ one month later. In it he wrote that the Scharnhorst ‘had definitely sunk in approximate position 72°16’N, 28°41’E’, which was about 80 nautical miles north-east of the North Cape.

In naval history this has become one of the most famous spots in the Arctic Ocean, a site spoken of with awe from Labrador to the White Sea, from Reykjavik to Cape Rybachi. It was officially recognized by the British Admiralty and has found its way into a host of textbooks, magazines and works of reference. For me it was destined to prove a source of endless trouble and frustration.

CHAPTER TWO

AN UNSUCCESSFUL ATTEMPT

THE NORTH CAPE BANK, FRIDAY 24 APRIL 1999

The expedition seemed to be cursed from the start. I should have realized that we were jinxed when we were still moored in Honningsvåg a few days earlier and were busy testing the diving vessel Risøy’s sophisticated ROV (Remotely Operated Vehicle). The pictures of the seabed relayed via the control cable to the control room were perfectly clear, but spreading out across the surface of the sea was a thin, rainbow-hued film of oil: hydraulic fluid was seeping out from somewhere. There was clearly a leak, and I should have taken steps to find out where it was. But I was blind – I was too eager to get away. The wind from the night before had died down. The sea was calm and above the Porsanger fjord the Arctic spring sky was a shimmering vault of blue and gold.

‘Shall we go?’ asked Stein Inge Riise, a diver from Vardø who never said no to the chance of an adventure, and who had built Riise Underwater Engineering into a highly qualified company specialising in risky underwater operations. Forty years old, fair-haired and full of life, he had made an international name for himself when, with the aid of the Risøy, a local ferry he had converted, in the autumn of 1997, acting on behalf of Anglia TV, Channel 4 and Norway’s NRK, he located the wreck of the British trawler Gaul at a depth of 300 metres on the North Cape Bank – a feat the British Ministry of Defence had dismissed as impossible.

Now my partner Norman and I had presented Stein Inge and his crew with a new and equally formidable task. First, by means of the Risøy’s ROV, we planned to examine the cables strewn across the seabed around the wreck of the Gaul, then to sail for 60 nautical miles eastwards in search of the wreck of the German battlecruiser Scharnhorst.

When, late that night, we dropped anchor at the spot where the Gaul lay, some 55 nautical miles due north of the North Cape, the weather was still favourable. We were in one of the most unpredictable stretches of ocean in the world, but just now the sea was as calm as a millpond. Bathed in the radiant light of the Midnight Sun, the Barents Sea looked like a sheet of silk.

If the weather was on our side, everything else was against us. We were dogged by a succession of mishaps – electronic and hydraulic problems – which Stein Inge and his crew fought hard to overcome. When the hydraulic cutter broke down, I realized that the cables would have to wait. Now, late on Friday evening, we were making our way eastwards, heading for the position Admiral Bruce Fraser had given as the spot where the Scharnhorst had met her doom, the place where the last witnesses, Backhaus, Feifer, Boekhoff and the others, had watched the battlecruiser disappear beneath the waves. Keyed up as we were, we had been on the go, with little sleep, for close on fifty hours. At a depth of 300 metres margins are narrow and the risks correspondingly great – added to which, our troubles had left me with a tight knot in my stomach.

‘Relax. I’ve a hunch we shall find the wreck, provided the position’s correct. I can feel it in my bones,’ Stein Inge said reassuringly. An incorrigible optimist, he viewed every assignment as a challenge.

‘I hope you’re right,’ I muttered in reply. But I couldn’t do anything about the thoughts that continued to revolve in my head. Was the position correct? What if we didn’t find the wreck? How long could we keep on searching? How long would the good weather last?

The last signal transmitted by the Scharnhorst to Admirals Nordmeer in Narvik and Gruppe Nord in Kiel had been picked up by the British wireless interception service at 19.30 – just before the launching of the last decisive torpedo attack. It read: ‘AM STEERING FOR TANAFJORD. POSITION IS SQUARE AC4992. SPEED 20 KNOTS.’

AC4992 was a grid square in the German Kriegsmarine’s secret chart of the Barents Sea. It referred to a position of latitude 71°57’N and longitude 28°30’E. According to the battlecruiser’s reckoning, when the battle entered its final phase she was thus 15 to 20 nautical miles further south than the British believed her to be. Who was right, Admiral Bruce Fraser on board the Duke of York, flagship of the Home Fleet, or Kapitän-zur-See Fritz Julius Hintze on board the Scharnhorst?

I had chosen to pin my faith on Fraser, whose fix was, I assumed, backed by the navigators of the thirteen Allied vessels. Hintze’s men had been stood-to for more than twenty-four hours in extremely harsh weather conditions. They had had little sleep and had twice been engaged in exchanges of gunfire with British cruisers – on one occasion in the middle of the day, when, in theory, the light should have been at its best. But could the Scharnhorst’s navigators have taken an accurate fix under such otherwise unpropitious circumstances? Had they succeeded in accurately pinpointing their ship’s position during the almost three-hour-long conclusive phase of the battle?

I doubted it, and all other available data suggested that Admiral Fraser knew what he was about when he reported the position of the sinking as 72°16'N and 28°41'E.

I had meticulously collected and studied fishing charts covering this region ever since April 1977, when, as a newspaper reporter on assignment on board the Gargia, I had written:

No fishing is more demanding than trawling in the Barents Sea. For proof you need only look at the muscular arms of the men who fish these waters – and the way those who have been at it for a number of years drink when they are ashore.

I have been long-lining, far out to sea, in January, when darkness reigned for twenty-four hours a day and crews were reeling on their feet after twenty hours without sleep. I have witnessed purse-seine fishing offshore and on the banks further out to sea; and I have taken part in fishing in the confines of the Norwegian fjords. But nothing can compare with trawling … It is not just because of the vast quantities of fish the trawls haul on board. It is also because of the taut, slippery wires, the solid steel of the bobbins and trawl doors, the whine and clang of the winches. Trawling is heavy industry moved out to sea.

I had spent hours in the Gargia’s wheelhouse poring over the vessel’s old charts, which prompted me to add:

And there are the charts, guides to a wondrous landscape beneath the waves. On these charts, creased and tattered from years of use, the major fishing grounds are thick with the captain’s own mysterious markings. There are charts on which are marked the wreck of the Scharnhorst and other underwater hazards likely to damage trawls, a jumble of jottings, figures and pencilled lines. These sheets are not mere registers of depths and meridians, the work of the Hydrographic Department; they are also the product and repository of years of hard-won practical experience.

All the charts I had studied told the same story. Precisely where Admiral Fraser reported that the Scharnhorst had gone down, due north of the underwater formation known to local fishermen as the Banana, stood an ominous cross: ‘Foul bottom! War wreck! Fishing inadvisable.’

By transferring these figures to the Risøy’s satellite navigation system we had settled on a rectangular search area, 7,000 metres long by 4,000 metres wide, centred on the position given by Fraser. When the sonar ‘fish’ was lowered overboard, the echo sounder revealed that the depth ranged from 290 to 310 metres. At a towing speed of 3 knots and with a distance between the lines of 300 metres, it would be possible to cover the whole area by means of the side-scan sonar in the course of some twenty-five to thirty hours.

‘Take a break, go and get yourself some sleep,’ Stein Inge advised me. ‘We’ll give you a shout as soon as the wreck comes up on the screen.’ I did as he said and went down to the cabin, where I lay watching the waves lap against the porthole, which was almost on the waterline. I couldn’t get to sleep. I had thought and dreamed about the wreck of the German battlecruiser ever since, as a small boy in my home town of Hammerfest, I had first heard talk of the big German naval base there whose operations encompassed the whole of western Finnmark and which had made its effect felt on the lives of both my parents’ generation and my own.

In those days the county of Finnmark was Europe’s last frontier in the north, an outpost standing four-square to the desolate wastes of the Arctic Ocean. But both the war and the years that followed had taught the world that in reality this isolated region was a crossroads, a place where vital strategic and geopolitical interests clashed head-on. A global demarcation line, a hostile frontier, ran through the Barents Sea from the coast of Finnmark in the south to the edge of the polar ice in the north – as the story of the Scharnhorst so vividly proved. To me it had become paramount to find the sunken ship. It symbolized the forces that had moulded my childhood, spent there on the shores of the Arctic Ocean. I thirsted after answers to the many puzzles surrounding the loss of this proud ship. What had caused a vessel that was considered to be unsinkable to sink? Why had she lost speed when she was close to escaping and Fraser had called off the hunt? What had caused the last explosions, those that had made the sea itself heave and shudder? What had happened to the close on two thousand men who had gone down with her?

There were other unanswered questions, too. Where did the decisive signals that encouraged the British to set up the perfect ambush come from? From those courageous Norwegian wireless operators who, at risk of their lives, kept the German naval bases under surveillance? Or was it true, as the official British history claimed, that these undercover agents had nothing to do with the matter? If that were so, why, considering the enormous risk involved for them and their loved ones, had they been stationed behind the enemy lines in the first place?

I must have dropped off, because later in the evening I was jolted into wakefulness by a voice saying, ‘The wind’s getting up. You’re wanted on the bridge.’

I knew from the way the Risøy was lurching about that all was not well. When I had stretched out on my bunk the waves had been gentle, lulling me to sleep. Now the ship was pitching and tossing with a choppy motion that made it difficult to keep one’s balance.

On the bridge the sonar operator had been awake for more than twenty-four hours. He was surrounded by cups black with the dregs of cold coffee and ashtrays filled to overflowing.

I glanced at the rolls of print-outs. ‘Found anything?’ I asked, though I was already sure of the answer.

‘Not a thing, apart from drag marks and pockets of gas. The seabed’s as flat as a pancake, you couldn’t hide a trawl door here, never mind a battleship.’

My heart in my boots, I studied the lines on the long strips of paper. Some 300 metres below our keel lay the ocean bed, scoured as clean as any dance floor, though scored here and there by the passage of retreating icebergs thousands of years ago. Never had I seen such a desolate expanse of ocean floor: devoid of life, it was nothing but an empty waste.

‘No sign at all of a wreck?’ I asked.

‘No.’

‘Nothing to suggest that we might be near the scene of a naval battle either – torpedoes, shellcases, nothing like that?’

‘Not so much as a dud.’

‘How long can we go on for?’

‘Another two hours or so, I’d say, with a bit of luck. There’s a gale forecast for later tonight.’

‘And how are things to the west?’

‘Look out of the window, you’ll see for yourself.’

I did. Some distance away to the west I saw the bobbing lights of hundreds of lanterns. It looked as though we were nearing a seaborne city. They were the lights of the international trawler fleet, which was heading for the coast in pursuit of the shoals of cod that were now on their annual migration to new feeding grounds.

‘They wouldn’t be fishing there if there was a wreck of the size we’re looking for on the bottom. They’d keep well away, that’s for sure.’

The sea had turned dark-blue. It boded no good. The wind was blowing with unabated force from the north-west, exerting an increasing and irresistible pressure that set the sonar winch in the stern creaking and groaning. Every time an extra-strong gust hit the Risøy’s blue-leaded hull, it was like a blow from a steam-hammer. For a fraction of a second the ship stood still, poised, then, pounding heavily, lurched onwards.

‘We shall have to bring in the sonar soon,’ the operator said. ‘There’s too much strain on the cables. We can’t afford to lose it. There’s no point in going on now, anyway.’

We had combed an expanse of ocean more than 25 square kilometres in extent around the position given by Fraser in his official report – and hadn’t found a thing. Where the 230-metre-long wreck of the steel colossus we were looking for should have been there was nothing but compacted clay.

All through the night, as the gale continued to rise in fury and the Risøy pitched and rolled as she battled her way towards the coast, down in the cabin I clung hard to my bunk. I was feeling sick at heart, worn out and dejected. I had staked everything on realizing my youthful dream: to find the Scharnhorst and solve the mysteries that still clung to Hitler’s last battlecruiser. And what had I found? Nothing. I had gambled and lost. It wasn’t the fault of Stein Inge and his crew, it was just that I had been too optimistic, too naïve and too inexperienced. I had forgotten how infinitely great the Barents Sea really was.

Up top, the waves continued to hurl themselves with undiminished ferocity against the Risøy’s superstructure. It was a storm of nearly the same intensity as that which had raged in the same area on 26 December 1943 and turned the Scharnhorst’s last voyage into a nightmare. Though sad and dispirited, at the same time I was suffused with a strange feeling of calm. To all intents and purposes the expedition had been a failure; but it had, after all, served to take me to where I had for so long wished to be – the place where that terrible battle had been fought. I was one step nearer to learning the true story. Moreover, I had discovered something important: Admiral Fraser’s ‘Despatch’ had been wrong. The battle had not been fought where the official reports and charts said it had.

While afloat, the Scharnhorst had been considered a lucky ship, a naval legend, a ship which time and again had succeeded in slipping away and eluding her pursuers. And even at the end no one had actually seen her sink – apart from the young sailors who were left to fight for their lives in the icy, oil-drenched waters of the Arctic.

And now we knew that no one could say exactly where she had sunk, either. The wreck wasn’t where it was supposed to be. The Scharnhorst had vanished for the last time.

With the coming of morning the North Cape began to loom ever larger to the south-west, a beetling, black, storm-lashed bastion crouched beneath a canopy of torn, ragged clouds. We had failed to find our quarry, but I couldn’t just give up. It would be wrong to say that I had found nothing. I had found a purpose. I knew now what I had to do. I had to retrace my steps, return to the original documents and talk to the men who were there. Only they could make my dream come true.

CHAPTER THREE

A TIME FOR DREAMS

NORWAY/GERMANY, CHRISTMAS 1943

Many people were waiting, hoping and dreaming as the Christmas of 1943 drew near. In a scenic little community in the district of Alta, in the far north of Norway, twenty-year-old Sigrid Opgård Rasmussen was awaiting the greatest event of all – the birth of her first child. That apart, gloom prevailed. The fourth year of the war had brought nothing but sorrow and disappointments. True, it was whispered that the Germans were in retreat on the Eastern front, but in western Finnmark victory and liberation still seemed a long way off. German troops continued to pour across the county on their way to the trenches and fortifications east of the River Litza. From the fjord local residents could hear the thunder of heavy guns whenever Hitler’s admirals set out to test the fleet’s armaments.

The thought of the child to which she was about to give birth made Sigrid feel that it was worth while holding on. She felt assured that one day peace would return and real life could be resumed – the life she had dreamed of and planned together with her husband Kalle (Karl).

Sigrid had first met Kalle in the summer of 1942 – a lithe, athletic young man with narrow, sensitive features from which a smile was never far distant. She had walked all the way down from the out-farm in the mountains where she spent her summers, and was feeling hot, sunburned and bursting with energy. When she rounded the corner there he was, sitting on the farmhouse steps, busy tucking into a bowl of sour cream. In some strange way, even then, she sensed his interest, although his real reason for being there was far more mundane. A friend of her brother Halvor, he had only come to buy eggs and cream, not to see her. Sigrid recalled her mother’s refusal to accept payment, claiming that the sum involved was too trifling. She had added, however, that as he was cashier of the municipal Highways Department and his work took him far and wide along the fjords, it would be nice if he could bring a little fish with him next time he called.

All through the autumn Kalle was an increasingly frequent visitor, and on Christmas Eve he was invited to join the family for dinner. What had begun as a vague show of interest had by then evolved into the beginnings of an ardent love affair. It was fun being with Kalle. An accomplished gymnast, he had a ready wit and loved play-acting. His imitations left his audience helpless with laughter. ‘I’d never met anyone like him before. He got people going, made them laugh, made them happy.’

April 1943 was the turning point. Sigrid and Kalle started going steady, and before long they were lovers. It had all been so natural: they delighted in each other’s company, trusted one another and began to plan a future together. Kalle had a steady job and an assured income, which meant a great deal in those days. When Sigrid found herself pregnant, neither of them was in doubt about the next step. They made their way to Kalle’s home town of Vadsø and got married. The date was 7 August, a red-letter day that provided a fitting conclusion to a perfect summer.

We lived at home with my parents as part of the family. All we had for ourselves was a bedroom. That summer and autumn was the best time of my life. In spite of the war and all the trials it brought in its train, we were happy and satisfied with our life together, and in material terms we wanted for nothing. We began to think about our next move. Kalle had already talked to his boss and we were on the lookout for a place of our own.

These halcyon days came to an end in November. Something had happened, and Sigrid feared the worst. It was all so very mysterious. Kalle had begun to spend more and more time with a friend from Vadsø, Torstein Pettersen Råby. Torstein was something of a prankster, but there was more to him than that. Sigrid couldn’t quite say why, but for some reason she felt uneasy. The two men increasingly spent their evenings together in the barrack-like hut that served as the Highways Department’s office in Kronstad. When Kalle returned home, late at night, he often reeked of cheap spirits. What was going on? Sigrid wondered. Why had her formerly so athletic husband suddenly taken to drink? When she pressed him for an explanation, Kalle was evasive. He was clearly under great strain.

He never said where he was going, not really, when he went out. I found myself anxiously awaiting his return, and I used to go to the window to look for him coming up the road. I oughtn’t to have done that really, but I was so on edge that I couldn’t help myself. I had a strong suspicion of what the two were up to, but I couldn’t be sure. Our marriage suffered because we couldn’t be open with one another. I did ask him, but he begged me not to push him. I cried and told him that people had begun to talk about his drinking. ‘That’s good,’ he said. ‘That means it’s working.’

By now it was only a few weeks till the baby was due; it was expected to be born around the turn of the year. A child born of love and bearing hope for the future, in the event it arrived early in the New Year. But Kalle was away somewhere, together with Torstein. His absence boded ill, and Sigrid was beside herself with worry. The war seemed to have come home to them personally. Twenty years of age, newly wed and with a new-born baby, she felt that her whole future was hanging in the balance.

Some 2,000 kilometres to the south, in the industrial city of Giessen in Hessen, in the heart of Hitler’s Third Reich, another young woman was similarly waiting, yearning and hoping. Like Sigrid Opgård Rasmussen, at that time Gertrud Damaski, vivacious and outgoing, was still in the bloom of youth; she was only eighteen. The two girls were completely unaware of each other’s existence. All they had in common was their youth – and their fear of what the war might do to their loved ones.

Gertrud came from humble circumstances. Her mother had died young and her father, a waiter, rarely returned home from work until late at night. To earn a living Gertrud had apprenticed herself to a goldsmith, a man who took great pains to teach her how to value, care for and repair watches and jewellery. The war had still not reached Giessen, though bombs continued to rain down over the cities of the Ruhr, some way to the north. Like so many young women, Gertrud wrote letters designed to cheer the hearts of unknown servicemen. That was her contribution to the war effort. One day in the spring of 1943 she was given a field post address by a friend and asked to pen another such ‘letter from home’.

The boy to whom I wrote was from Annerod, a village close to Giessen. His name was Heinrich Mulch and he was twenty-one years of age. I didn’t know him, and never expected an answer. I only wrote to him to cheer him up. I saw it as my duty.

To Gertrud’s surprise, some weeks later the postman delivered an envelope to her home.

‘My dear little unknown girl, I have just received your lovely letter, for which I thank you very much. It gave me great pleasure, even though as yet I do not know who you are … and if you write again, I promise you an answer.’

I’d no idea of where Heinrich was or what he was doing. Everything was shrouded in secrecy and censorship was very strict. He would have been punished if he’d told me anything like that. But we continued to correspond, often writing to each other several times a week, until, one day, he suddenly turned up outside the goldsmith’s shop. My Heinrich had been granted leave.

Gertrud’s simple, friendly letter had kindled a flame. The two hit it off from the outset. ‘It was as if we had known one another all our lives. That kind of thing happens sometimes. Some people you just take to right away, and that’s the way it was with us. It simply happened, all of a sudden.’

Both Heinrich and Gertrud had had a strict upbringing. Because of that their meetings had to be conducted with due decorum – except when they could stroll together in the evenings beside the River Lahn. They held hands, embraced and exchanged stolen kisses.

It was on one of our last evenings together. I asked him where he was stationed.

‘That I’m not allowed to say,’ he said.

I insisted. ‘I must know. I have to know where you are.’

He hesitated for a moment, then blurted out, ‘Tirpitz’.

I didn’t understand what he meant. ‘Tirpitz, where’s that?’ I asked.

‘Tirpitz is a battleship,’ he said. ‘It’s stationed in the far north. I’m a writer on the Admiral’s staff.’

All that autumn passionate letters continued to pass to and fro between Giessen and the Kå fjord in northern Norway. Things were quiet at the naval base. The flagship was undergoing repairs. Many of the men were given leave or sent back to Germany on refresher courses. Heinrich, one of the few of his shipmates to have attended commercial school, applied to a naval college in Frankfurt and was accepted. That was why Gertrud was so happy and full of hope. She could complete her apprenticeship and get a job with a goldsmith in the same city and they would be able to spend the rest of the winter together. It would be the first winter they had done so since falling in love. Now, all that remained to be settled were a few formalities. The final decision was to be taken early in the New Year. Christmas was fast approaching, but Gertrud was determined to wait until all was officially in order. ‘You have given me beauty, trust, love and faith in a wonderful future together. I shall always be devoted to you,’ Heinrich had written.

The war continued in mounting fury. To Gertrud it seemed oppressive and meaningless. What kept her going was the thought of Heinrich. The days dragged, but she had long ago learned – knew, in fact, deep within her heart – that love, above all else, was worth waiting for.

II

CHAPTER FOUR

OPERATION OSTFRONT

WOLFSSCHANZE, EAST PRUSSIA, 1 JANUARY 1943

Adolf Hitler’s rage knew no bounds. His frail body visibly shook. He ranted and raved and hammered the table with his fists. He had celebrated New Year’s Eve in a good mood, despite increasingly dismal despatches from Stalingrad, where von Paulus’s Sixth Army was nearing annihilation. To the Nazi satraps and top-ranking generals who made their way to Rastenburg to wish their Führer a Happy New Year, he elatedly confided that they were in for a pleasant surprise. Early that morning the pocket battleship Lützow and the heavy cruiser Hipper, together with six destroyers, had attacked a weakly protected convoy 50 nautical miles south of Bear Island. In Hitler’s feverish imagination northern Norway was still the place where the outcome of the war would be decided. It was in the north, he believed, that the Allies would open a second front; and it was there that the decisive battle would be fought. It was for this reason that he had personally followed the preparations for Operation Regenbogen (Rainbow) and demanded that he be kept abreast of developments.

Hitler’s good humour was ascribable to the news of the operation that he had received up to then. As early as 09.36 the commander of the Battle Group, Vizeadmiral Oskar Kummetz, reported that he had ‘engaged the convoy’. Two hours later he sent a new signal to say that there were no British cruisers in the vicinity of the merchantmen.

The skipper of U-354, Kapitänleutnant Karl-Heinz Herbschleb, followed the course of the battle through his periscope, as the inky blackness of the Arctic sky was repeatedly rent by the flashes of heavy guns. At 11.45 he wirelessed, ‘FROM WHAT I CAN SEE FROM HERE THE BATTLE IS NOW AT ITS HEIGHT. ALL I CAN SEE IS RED.’

At the Führer’s headquarters, the Wolfsschanze (Wolf’s Lair), deep in the East Prussian forests, the only interpretation that could be placed on the two signals was that Kummetz was in the process of destroying the convoy. It augured a resounding victory, a victory Hitler intended to announce to the German people on New Year’s Day.

But as the night wore on, Hitler’s trepidation grew. The flow of wireless signals had ceased and a curtain of silence seemed to have descended on the Arctic Ocean. The Kriegsmarine’s liaison officer, Vizeadmiral Theodor Krancke, did his best to reassure his increasingly impatient Führer.

‘Kummetz has imposed wireless silence in order not to disclose his position,’ he said. ‘There may be heavy enemy naval units in the area. As soon as he reaches the safety of the coast, we shall have good news.’

But that was not enough to pacify Hitler. Instead of retiring for the night, he paced restlessly to and fro across the floor of his headquarters sanctum. Early the next morning, when Reuters issued a brief bulletin that had just been released by the Admiralty to the effect that the German attack had been beaten off and that the convoy had safely reached Murmansk, Hitler’s pent-up fury exploded. He lost no time in venting his rage on the hapless Krancke and demanded an immediate and full explanation. He declared that he no longer had any confidence in his admirals and that everything suggested that they were deliberately withholding the truth from him.

The British report of the outcome of the battle was correct. The Lützow and Hipper had indeed found the convoy, but Kummetz, hampered by the constraints that governed his dispositions, had acted hesitantly and indecisively. His orders for the operation, which had been approved by Hitler, forbade him to take ‘untoward chances’ with his cruisers. Moreover, Otto Klüber, the admiral commanding Northern Waters, had reiterated the order, wirelessing while the battle was actually in progress, ‘TAKE NO UNNECESSARY RISKS.’

Kummetz was no Nelson and carried out his orders to the letter. When the commander of the British escort vessels, Captain Sherbrooke, gallantly led his inferior force in to attack the two cruisers, Kummetz withdrew under heavy shelling. The British lost the destroyer Achates and a minesweeper, the Bramble, and several other vessels suffered damage, but the convoy itself escaped. And when the outlying escort, which consisted of the two cruisers Jamaica and Sheffield, finally reached the scene, the German destroyer Friedrich Eckholdt was sent to the bottom and the Hipper was almost disabled by a shell that penetrated to her engine-room.

As the morning progressed, Fleet Headquarters in Berlin made several unsuccessful attempts to contact Kummetz. But the teleprinter link to the Kå fjord was out and atmospherics made wireless communication difficult.

By five in the afternoon Hitler could contain himself no longer. He summoned Vizeadmiral Krancke and, beside himself with fury, declared that the Navy’s big ships were utterly useless. Since the early days of the war, he fumed, they had caused him nothing but worry and disappointment, so much so that they had become a liability and a burden on the war effort. He continued: