Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

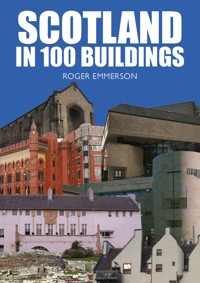

Scotland in 100 Buildings by architect Roger Emmerson is a captivating journey through the architectural marvels of Scotland, seen uniquely through Emmerson's personal experiences. This isn't a dry history or textbook – it's a lively, intimate account where each building tells its own story. Emmerson has visited every site featured, offering first-hand insights that bring these places to life, from iconic landmarks to hidden gems. His reflections aim to inspire readers to explore for themselves, rather than simply inform, making this book easy to pick up at any page. Ideal for architecture enthusiasts, travellers and locals alike, Scotland in 100 Buildings will appeal to anyone curious about Scotland's diverse buildings and the personal tales they inspire. It's perfect for those seeking an approachable and authentic look at Scotland's architectural legacy.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 183

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ROGER EMMERSON was born in Edinburgh and attended Leith Academy. He studied architecture under Sir Robert Matthew at the University of Edinburgh and under Professor Isi Metzstein at the Glasgow School of Art, graduating from there in 1982. He has worked in London, Newcastle upon Tyne and, mostly, Edinburgh, running his own practice, ARCHImedia, from 1987 to 1999 while concurrently teaching architectural design at Edinburgh College of Art when he was also visiting lecturer at universities in Venice, Lisbon, Stockholm, Copenhagen and Berkeley. Since 2000 he has worked extensively in the fields of architectural conservation, housing, education and the leisure industries throughout the UK, retiring from architectural practice, although not architecture, in 2016. He is married and lives in Edinburgh close to his four children, their partners and his seven grandchildren. He devotes his free time to writing, painting and playing guitar. On the odd occasion he makes a list, he rarely sticks to it.

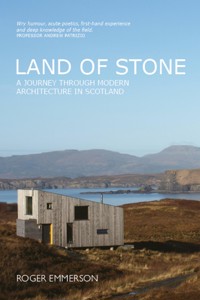

By the same author:

Land of Stone: A journey through modern architecture in Scotland, Luath Press, 2022

My late mother and father drove virtually every road across a Scotland they loved, visiting many of these buildings and more. This book’s in memory of them.

First published 2025

ISBN: 978-1-80425-173-7

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

The paper used in this book is recyclable. It is made from low-chlorine pulps produced in a low-energy, low-emission manner from renewable forests.

Typeset in 9.5 point Sabon by

Main Point Books, Edinburgh

All photographs and illustrations © Roger Emmerson unless otherwise stated.Text © Roger Emmerson, 2025

Contents

Introduction

Using the book

Geographic List of Entries

Map of Scotland

PREHISTORY

Skara Brae

Maes Howe

Calanais Standing Stones

Tomnaverie Stone Circle

Ring of Brodgar

Broch of Gurness

MEDIAEVAL

St Magnus Cathedral

Dirleton Castle

Caerlaverock Castle

Lochranza Castle

Crichton Castle

St Machar’s Cathedral

Rosslyn Chapel

Kirbuster Farm Museum

Claypotts Castle

Tankerness House

The Study, Culross

Lamb’s House

RENAISSANCE

Craigievar Castle

Gladstone’s Land

George Heriot’s School

Inveraray

Gunsgreen House

Paxton House

Stobo Castle

REVIVALISM

Royal High School

Balfour Castle

Cathedral of the Isles

The Blackhouse

Gardner’s Warehouse

Holmwood

St Vincent Street UP Church

Lammerburn

Barclay Bruntsfield Church

Wallace Monument

Kibble Palace

Fountainbridge tenement

National Museum of Scotland

The McManus: Dundee’s Art Gallery and Museum

Grecian Chambers

Mortuary Chapel

Queen’s Cross Church

St Conan’s Kirk

John Morgan House

Central Library

Templeton’s Carpet Factory

Kirkton Cottages

Mansfield Traquair Centre

DÉBUT DE SIÈCLE

Melsetter House

St Vincent Chambers (The Hatrack)

Hill House

Daily Record Printing Works

St John the Evangelist RC Church

Willow Tea Rooms

Riselaw House

Lion Chambers

St Peter’s RC Church

RW Forsyth’s

Duke Street Church Halls

John Paris Building

Artist’s Studio

Grangewells

Hippodrome

EARLY MODERNISM

Scottish National War Memorial

Reid Memorial Church

St Andrew’s House

The Lane House

Dunfermline Fire Station

Jenners Flats

Kirkcaldy Town House

Rothesay Pavilion

Palace of Art

St Peter-in-Chains RC Church

Italian Chapel

LATE MODERNISM

Pitlochry Dam

Telephone Exchange

St Paul’s RC Church

Canongate Housing

Sillitto House

Gala Fairydean Stadium

Andrew Melville Hall

Cumbernauld Town Centre

Edenside Medical Practice

Burrell Collection

Eden Court Theatre

Dundee Repertory Theatre

21st-Century Tenement

House for an Art Lover

THE MILLENNIUM

Museum of Scotland

Dundee Contemporary Arts (DCA)

The Scottish Parliament

Homes for the Future

Pier Arts

Sandiefield Housing

Murphy House

The Three Bridges

V&A Dundee

Queen Street Station

Simon Square Housing

Edinburgh Futures Institute

Timeline

Glossary

Bibliography

Illustration Credits

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Why Scotland in 100 Buildings? Well, there’s a unique story here that can be told through the structures that Scots, and others, have erected in Scotland over a period of 5,000 years. Of course, Scotland in 100 Buildings is a list. Lists can be fun, sometimes irritating, occasionally infuriating, but also instructive, since what’s left out is as significant as what’s included. So it would useful for you to know what I mean by ‘Scotland’ and ‘buildings’ and how I made my selection.

‘Scotland’ is the Scotland shown on present-day maps and terminates at the current legal boundary with England. This means I’ve excluded Berwick upon Tweed although it seems a real Scottish burgh to me.

My definition of a building is any structure erected for human use even if we are not always sure what that use might have been. I’ve included tombs, funerary monuments and, contentiously perhaps, stone circles, bridges and a sma burgh.

Like many architects, when asked to name a favourite building, I have, often enough, chosen one I have never seen other than as a photograph or drawing in a book; my choice being purely aesthetic or conventional. In giving public talks I would ask that same question of those present. Their choices, almost exclusively have a personal story to tell. Their favourite building is experienced wholly through the context of that story, and not as an object thought of as beautiful or significant in itself. I have adopted the same approach, while hoping also to impart some architectural, aesthetic or historic information.

Buildings do not feature in this list unless I have visited them, preferably have been inside them, although that was not always possible. We all bring our own cultural and personal baggage to our direct sensory experience of a building; my accounts are simply an encouragement, not an instruction.

Architects writing about architecture tend to write for other architects. I’ve done that myself often enough. Nevertheless, there’s no harm in imparting purely architectural information if it’s central to explanation, to the story; a little architectural history is a good thing, but more than that is too much.

How should Scotland in 100 Buildings be arranged? Should entries be grouped by type – churches, houses, factories – or by location – Glasgow, Eyemouth, Hoy – or by architectural themes – Classicism, Gothicism, Modernism, Expressionism? My aim is to tell a story; so I’ve adopted a linear narrative with a beginning, middle and provisional end and arranged entries chronologically. Although this is not a history of Scottish architecture, buildings are grouped in eight sections to give some contemporary context: Prehistoric, Mediaeval, Renaissance, Revivalism, Début de Siècle, Early Modernism, Late Modernism and the Millennium.

Using the book

EACH ENTRY GIVES the commonly accepted name for the structure, its location, date and designer, if known. Each building location is numerically identified on the map of Scotland on page 13. Many of the sites have visitor centres and websites describing opening times. Some are private dwellings or simply closed. Please respect the owners’ and neighbours’ privacy. Some require booking or have severely restricted opening times. Nearby buildings within a roughly 10 minute walk are identified.

While Scotland in 100 Buildings is intended as a guide to be dipped into as required, it can equally be read as the story it purports to tell with the section introductions setting the scene.

Geographic List of Entries

Aberdeen 12, 42, 44

Alford 20

Arbroath 41

Ardrossan 73

Bo’ness 60, 62, 63

Caerlaverock 9

Crichton 11

Culross 17

Cumbernauld 82

Dirleton 8

Dundee 15, 39, 86, 90, 97

Dunfermline 68

Edinburgh 18, 20, 21, 26, 33, 34, 37, 38, 45, 48, 53, 55, 57, 58, 59, 61, 64, 65, 66, 67, 69, 76, 78, 79, 89, 91, 95, 99, 100

Eyemouth 23

Fortingall 47

Galashiels 80

Glasgow 30, 31, 32, 36, 40, 46, 50, 52, 54, 56, 72, 84, 87, 88, 92, 94, 98

Glenrothes 77

Helensburgh 51

Inveraray 22

Inverness 85

Kelso 83

Kirkcaldy 70

Lewis 3, 29

Lochawe 43

Lochranza 10

Millport 28

Orkney 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 14, 16, 27, 49, 74, 93

Paxton 24

Pitlochry 75

Queensferry 96

Roslin 13

Rothesay 71

St Andrews 81

Stirling 35

Stobo 25

Tomnaverie 4

Map of Scotland

Prehistory: 1–6

EMPLOYING A MEASUREMENT from the rule-of-thumb system that includes the ‘length of a London omnibus’ or the ‘size of Wales’, ‘old as the pyramids’ is frequently used to comparatively date other constructions. The pyramids are the obvious signifiers of a complex Egyptian culture which possesses extensive written records – a history – inscribed in hieroglyphs inked, painted or carved on every surface, other than the pyramids, accompanied by copious illustration and statuary. Our knowledge is not complete and mysteries remain.

Scotland’s ancient cultures, however, are only imperfectly revealed in stone circles, chambered tombs, brochs, burial goods, pottery and other random objects and in the landscape; nothing is written down. In the strict meaning of the word, then, Scottish cultures are pre-historic even up to quite recent times. Such documentary evidence as exists comes from much later when myth and legend tell of a Celtic hegemony in present-day Scotland, Ireland, Wales and Western France.

Julius Caesar’s Commentarii de Bello Gallico of 58–49 BCE, about his wars in France, introduced the Druids. In Ireland 8th-century monks collected stories from the oral tradition to assemble a pre-Christian ‘history’ in the Lebor Gabála. One thousand years later, a similar methodology was employed in Scotland by James Macpherson with the publication of four books on the Ossian myth between 1760 and 1765. Each of these texts was designed to satisfy contemporaneous objectives: Caesar’s self-aggrandisement; Irish monks’ scholasticism; Macpherson’s other side of the Enlightenment coin; and for New Age Druids a more earthbound, quasi-democratic belief system. The prevalence of prehistory in Scotland makes for its real presence inscribed in structures in the landscape not text in a book.

Skara Brae

1

Skara Brae

Bay of Skaill, Orkney, 3180 BCE

SKARA BRAE, PART of the Orkney UNESCO World Heritage Site is, of course, older than the pyramids.

I first visited the location in the early 1980s, in the days before Orkney’s tourism boom and status as preferred cruise ship destination, when it was still permissible to wander round within the houses and the connecting passages.

Sat in a house, surrounded by the built-in beds, storage recesses, lamp sconces, shellfish tanks, fire pit and ‘dresser’, all built from the thin-bed Orkney sandstone due to the scarcity of timber (saved for the roof), the presence of the past in the present was overwhelming. It was entirely possible to reconstruct a life in this setting. I knew where everything should be put, stored or displayed, who sat on which side of the fire pit, slept in which bed, the conversation that might be had, the neighbours one might meet who had just negotiated the sheltering passage to join in.

As a designer, I am captivated by the construction and how the thin-bed ‘Walliwall’ stone enables considerable manipulation of form in recesses, curves and corbelling and is used either flat ‘on bed’, or vertically on end to satisfy different constructional needs; house plans vary from nearly square with rounded corners to amorphous, some with cave-like store rooms off the main space. There is no question in my mind that the ‘dresser’ is anything other than conscious design where decisions were made about thickness of stone, whether laid on bed or vertical, whether presenting on edge or on face and where jointed.

CHECK WEBSITE FOR OPENING TIMES

NEARBY: 14KIRBUSTER FARM MUSEUM

Maes Howe and the mountains of Hoy beyond

Maes Howe plan and section

2

Maes Howe

Stenness, Orkney, ca. 2800 BCE

MAES HOWE is part of the Orkney UNESCO World Heritage Site. It is the largest and most sophisticated of the ‘Maes Howe’ type of chambered tomb, unique to Orkney. It is aligned with other nearby monuments and there is a Neolithic ‘low-road’ that connects it to Skara Brae.

The masonry techniques and the implicit design intent evident at Skara Brae have been refined and ordered in plan and section to ratify the sense of a ‘holy’ space. The constricted entrance passage – roughly 90cm high, less wide, 11m long – is flanked and roofed by single masonry slabs almost the full length of the passage. It opens out into the buttressed square central chamber 4.6m almost the full length of the passage with wall and ceiling masonry now 3.8m high although probably originally 4.6m high, the roof lost first to Viking tomb-robbers and then to James Farrer’s crude 19th-century excavation. Three small low-ceilinged crypts open off the centreline of each side but dog-legged so that the interior of each crypt remains hidden. The walls and ceiling/roof of the central chamber, formed of thin-bed Walliwall, are corbelled from just above head-height, beehive fashion, to create a vault. The four supporting buttresses are flanked by single full-height stones which may be repurposed standing stones from a former stone circle on the site, shaped to follow the in-curving line of the ceiling. The tomb has been designed and assembled with some degree of precision. With an obscuring bend in the entryway now missing, Maes Howe is oriented to permit the rays of the sun at the winter solstice to strike the back wall of the chamber. A trilithon, such as is found at Stonehenge, is a feat of engineering; Maes Howe is a work of architecture.

CHECK WEBSITE FOR OPENING TIMES

NEARBY: 5RING OF BRODGAR

Standing Stones of Calanais

Plan

3

Calanais Standing Stones

Lewis, ca. 2500 BCE

THE CALANAIS STONES, more properly Calanais 1, are part of several Neolithic structures sited within a matter of a kilometre of each other on the west coast of Lewis. The stones of Lewisian gneiss, 1.7–3.0 billion years old, are erected on an eminence above Loch Roag framed by the hills of Great Bernera to the west and are topographically positioned to focus on the distant landscape form of the sleeping goddess, the Cailleach Na Mointeach. At Calanais the standstill moon rises out of a mountain that looks like a woman lying on her back with her knees raised. The several neighbouring structures, Calanais 2 and 3, suggest this was a centre of significant Neolithic ritual activity.

Calanais 1 is arranged as a small circle with a tall near-central single stone. An ‘avenue’ of two near parallel lines of stones runs roughly north northeast and shorter single lines of stones run roughly east southeast, south, south southwest and west northwest of the circle. Orientation of the stones suggests that the form is planned astronomically on the rising and setting of the equinoctial sun but principally on the cycle of the moon and on the extreme southern and northern moonrises of the ‘standstill’ moon that occurs every 18.6 years. The avenue may have been the means by which the celebrants entered the circle.

This is a monument that demands you wander through it, contemplating its complex cosmological and religious purposes and joining in one’s progress with the many thousands in earlier times who have made their way to its heart and to the heart of its present mystery.

CHECK WEBSITE FOR OPENING TIMES

NEARBY: 29THE BLACKHOUSE

Tomnaverie Stone Circle

Plan

4

Tomnaverie Stone Circle

Aberdeenshire, 2500 BCE

TOMNAVERIE IS ONE of the smaller stone circles, ca. 17m across, and sits on a low hill 178m above sea level. It’s what is known as a recumbent stone circle from the very large and prominent stone, in this case weighing about 6.5 tons, laid on its side and flanked by two stones taller than the rest. Such recumbent stones tend to be oriented so that one’s view, framed by the flanking stones, faces south southwest.

As with all of these monuments there is much speculation about astronomical orientation and the positioning of significant parts of the circle do align with known astronomical events. Ancient peoples were farmers, fishers and hunters for whom knowledge of the seasons was critical. I have to assume they were not unobservant and that their metaphoric book of temporal knowledge and calculation was the sky and the position of the sun, moon, planets and stars within it. Tomnaverie, of course, in addition to the possible astronomic orientation of its several stones, is planned to focus on the gap to the west of Scar Hill which frames Lochnagar (Beinn Chìochan) 30km distant to the south southwest, and which reveals itself as a Cailleach, a sleeping goddess, thereby overlaying further religious and cultural significance on the circle.

CHECK WEBSITE FOR OPENING TIMES

Ring of Brodgar

5

Ring of Brodgar

Stenness, Orkney, 2500–2000 BCE

THE RING OF Brodgar is part of the Orkney UNESCO World Heritage Site. It’s the third largest stone circle in the UK, 104m in diameter, and, bearing in mind the nearby geometric precision of Maes Howe, the only one a near-perfect circle. The Ring is related to the Neolithic settlement of Barnhouse (ca. 3300 BCE) on the matching south eastern promontory and the adjacent Stones of Stenness. Several other monuments are associated with it.

Since 2003, excavation to the immediate southeast of the Ring at the Ness of Brodgar has revealed a massive complex of monumental Neolithic buildings roughly contemporaneous with the Barnhouse settlement on a three hectare site. The substantial finds made there are still being evaluated.

Other than size, it is possibly the siting of the Ring of Brodgar that is its most significant feature. It sits on a natural raised platform on the narrow isthmus between the freshwater Loch Harray and the sea loch of Stenness within a bowl formed by Orkney’s hills: Greening Hill, Skalday to the north; Mid Tooin to the northeast; Keelylang, Burrien and Wideford Hills to the east; Ward Hill, Orphir to the southeast; Ward Hill, Hoy to the southwest and the Hill of Miffia to the west.

To stand in the centre of the Ring is to stand within two concentric circles, one natural, the other made by humans. The power of the place is palpable and gives reason to the siting of the Ring as celebration and replication of the bowl of the earth beneath the vast dome of the sky supported on those hills or on the symbolic columns of the stones.

CHECK WEBSITE FOR OPENING TIMES

NEARBY: 2MAES HOWE

Broch of Gurness

Broch of Gurness, plan

6

Broch of Gurness

Aikerness, Orkney, 500–200 BCE

THE BROCH OF Gurness, walls now reduced to 3.6m high, commands a low clifftop location overlooking Eynhallow Sound with Eynhallow to the northwest and the much larger Rousay to the north. Eynhallow is from the Old Norse Eyinhelga, meaning holy island. It is almost impossible in Orkney to be more than a kilometre distant from some ‘holy’, ceremonial or ritual site. Aikerness is dotted with tumuli and chambered tombs and four further ruined brochs line the shore north of Gurness for about 4 kilometres. Brochs are unique to Scotland (some 571 have been identified, mostly in Northern Scotland and in the Northern and Western Isles). Their use is uncertain and they may have been offensive or defensive structures or demonstrative of local wealth.

Occupation of the site at Gurness is various with its original inhabitants having abandoned it by 100 CE although it was still settled until 500 CE in Pictish times and evidence of Viking burials from 900 CE has been found. The broch is circular with an open central space ca. 10m in diameter surrounded by massive four metre thick walls, gradually diminishing in thickness as they rise, which contain stairs, small chambers and stores; what came to be known as the ‘inhabited wall’. The substantially complete Broch of Mousa in Shetland, on a smaller ground plan, is 13.3m high and one might suppose a similar original height at Gurness. There is evidence that brochs had at least two internal timber floors supported on timber posts and would have been roofed with timber beams possibly bearing large thin slabs of Walliwall.

CHECK WEBSITE FOR OPENING TIMES

Mediaeval: 7–18

‘MEDIAEVAL’, AS A CATEGORY, is imprecise and so often denotes the purely romantic: ‘merrie England’, the novels of Sir Walter Scott and William Morris and the works of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. However, since the buildings I have chosen range from 12th-century Romanesque to 14th-century castellated forms, some of which incorporate later Gothic and Renaissance additions of the 14th, 15th, 16th and early 17th centuries, I needed a loose parentheses. Perhaps the single formal significance of the period is the endurance of the Romanesque or Norman rounded arch in Scotland alongside, even in preference to, the pointed Gothic arch which, by the 13th century had supplanted the Romanesque elsewhere in Europe. In particular, the extended construction period for cathedrals and castles (one could argue that cathedrals are never truly completed) has them spanning centuries and different architectural idioms.

Moreover, the wars of conquest and independence that raged throughout this period seemed to require that all major constructions be fortified to provide shelter to their inhabitants whether knights, scholars, parishioners or peasants. The sturdier, plainer and more economic forms of the Romanesque were possibly better suited to this than the relatively fragile and costly stressed masonry gymnastics and decorative complexities required of the Gothic.

St Magnus Cathedral

Inside St Magnus Cathedral

7

St Magnus Cathedral

Kirkwall, Orkney, 1137

THE BEST WAY to see St Magnus Cathedral, just as one might best experience the Campanile of St Mark’s, Venice, is from the deck of a boat putting in to harbour. You might even combine it with a return journey from Balfour Castle on Shapinsay 27