Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

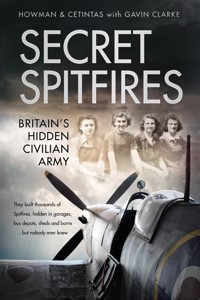

September 1940: In the midst of the Second World War, The Luftwaffe unleashed a series of devastating raids on Southampton, all but destroying its Spitfire factories. But production didn't stop. Instead, manufacturing of this iconic fighter moved underground, to secret locations staffed by women, children and non-combatant men. With little engineering experience between them, they built a fleet of one of the greatest war planes that has ever existed. This is their story.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 315

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2020

This paperback edition first published 2022

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Ethem Cetintas & Karl Howman, 2020, 2022

The right of Howman & Cetintas to be identified as the

Authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with

the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75099 550 4

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Foreword by Maggie Appleton MBE, CEO RAF Museum

Foreword by Maj. Gen. (ret.) Frederick F. Roggero USAF

High Flight

Introduction: Building a Legend

John Gillespie Magee Jr: A Remarkable Life

The Engineering and Design that Made the Spitfire Special

Chapter 1: The Road to Dispersal

Spitfire Supply Lines Uncovered

Race and Reaction: Birth of the Spitfire

We Saw it Burn: Testimony from Inside the Firestorm

Secret Saviour of the Spitfire

Chapter 2: People and Places of the Secret Factories

By the Numbers: Secret Factories’ Facts and Figures

A Walk Through Supermarine’s Hidden Design HQ

How to Hide a Workforce

This Island Salisbury: War Comes to the City

Chapter 3: Day in the Life of a Factory

Beatrice Shilling: The Woman who Saved the Spitfire

Careless Talk Costs Lives

From Prototype to Production

Uncle Sam’s Rolls-Royce Engines

Chapter 4: Take it Away: Test Pilots, Danger and the ATA

Life on the Edge: The Test Pilots’ Story

One Idea, 24 Marques: Welcome to the Versatile Spitfire

Spitefuls and Seafires

The Spitfire in Pieces

Chapter 5: Clocking Off: Life Outside the Factory Shift

Not Just Digging for Victory

Salisbury’s Stars and Stripes Hospital

Radio Days that Shaped a Nation

The People of Secret Spitfires

Norman Parker: From Barnardo’s Boy to Spitfire Historian

Secret Spitfires’ Next Chapter

About the Authors

Credits and Contributors

Notes

FOREWORD

MAGGIE APPLETON MBE, CEO RAF MUSEUM

It’s a real privilege to be asked to contribute to a book that reveals the incredible story of the Secret Spitfires. When the documentary team shared their vision with me some years ago of uncovering the lost history of Spitfire production during the war, it was clear they had discovered a real gem of a tale – something that needed to be polished and placed on full public display for the world to appreciate.

The narrative uncovered in this book aligns beautifully with the RAF Museum’s mission to inspire everyone with the RAF story – the people who shape it and its place in our lives. Secret Spitfires is a story of British character, determination, bravado, joy and pain. It is a story of ordinary people – the majority of them women – standing up, very quietly and modestly, to the forces of Hitler that had bombed Southampton’s major Spitfire works in the mistaken belief that destroying them would diminish the threat posed by the Royal Air Force. The thrill and sheer impertinence of these dispersed Spitfire factories, ‘hidden’ in plain sight, was clearly a story begging to be told.

Around 10,000 Spitfires were built covertly across a network of garages, bus depots, outbuildings, garden sheds, even in spare bedrooms, making a critical difference to the war effort. And at a time when nothing can escape the social media spotlight and every voice clamours to be heard, it is remarkable that, until very recently, these women and men remained silent about their extraordinary contribution.

Once given the opportunity to reveal their stories, however, the most amazing characters have shone through. Their testaments bring to life teams of individuals who played their part in the manufacture of components for this most iconic of aircraft. They had only limited knowledge of the scope of their enterprise and yet continued to work with a clear and steadfast pride and faith that somehow makes this story even more meaningful and significant.

Secrets sometimes need to be told. This is one of those times.

FOREWORD

MAJ. GEN. (RET.) FREDERICK F. ROGGEROUSAF CHAIRMAN, ROYAL AIR FORCEMUSEUM AMERICAN FOUNDATION

In our twenty-four-hour media age it is debatable whether a story could ever remain secret, let alone for 70 years. It is therefore not surprising that the producers of the film Secret Spitfires greeted the discovery of the story of covert production of Spitfires during the Second World War with a degree of scepticism. How could the manufacture of one of the most iconic aircraft ever produced have occurred behind nondescript facades in southern England, particularly in a small rural city such as Salisbury? But this is exactly what happened and the research unfolds amazing stories of Spitfires being built in secret, mainly by women. You didn’t talk about such things during the war and, even now, it took all powers of persuasion to extract the fascinating stories from the women who worked on those production lines.

With thousands of men away serving in the armed forces, British women played a vital role by not only running their households, managing a daily battle of rationing, recycling and growing produce but also by answering the call to become mechanics, bus drivers, engineers and munitions workers. This story not only reveals how these women found themselves on a factory line, but also how the filmmakers’ investigations peeled away the layers of secrecy that surrounded their war work. The result was an exposure of an amazing tale initially told in the film. However, the amount of research and hours of interviews extracted from these pioneering women was too much for one film so this book tells for the first time their incredible stories in full.

By 1944 up to half a million American servicemen were based in Britain working with the RAF to take on the Third Reich in the air and on the ground. More than 200 airfields were occupied or newly built by the United States Army Air Force (USAAF), with each one housing around 2,500 men – many times the population of nearby villages. Secret Spitfires highlights the very positive effect their presence had on the morale of the hard-pressed British. It reflects on the huge impact they had on British life and how they changed the places they inhabited, not least Salisbury. On their departure, they left behind them an enduring legacy and fond memories for those they met.

As Chairman of the RAF Museum American Foundation and a Trustee of the Foundation of the National Museum of the United States Air Force, it was my honour to help facilitate the North American premiere of the film Secret Spitfires in the museum’s IMAX cinema in 2019. On a wet and windy night, just a few days before the seventy-fifth anniversary of D-Day, approximately 240 residents of Dayton, Ohio – the birthplace of modern aviation – learned how a secret army of mostly women significantly contributed to the vital war work of the Allies by ensuring that Spitfires were ready to fly and fight in defence of freedom.

HIGH FLIGHT

Oh! I have slipped the surly bonds of Earth

And danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings;

Sunward I’ve climbed and joined the tumbling mirth of sun-split clouds, – and done a hundred things

You have not dreamed of – wheeled and soared and swung

High in the sunlit silence. Hov’ring there,

I’ve chased the shouting wind along, and flung

My eager craft through footless falls of air …

Up, up the long, delirious, burning blue

I’ve topped the wind-swept heights with easy grace

Where never lark, nor e’er eagle flew –

And, while with silent lifting mind I’ve trod

The high, untrespassed sanctity of space,

Put out my hand and touched the face of God.

Pilot Officer John Gillespie Magee Jr, 3 September 1941

INTRODUCTION

BUILDING A LEGEND

Soldiers, sailors and airmen through the centuries have taken up arms and – while it’s not uncommon to give your gun a name, call your ship a ‘she’ or paint a face on the nose of your bomber – few have been sufficiently inspired to dedicate a poem to the weapon under their control. Until, that is, Pilot Officer John Gillespie Magee Jr put pen to paper in the summer of 1941.

A young American with film-star good looks, Magee was on course to study at the prestigious Yale University on a scholarship but pulled out to answer the call of duty by enlisting with the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) before his own country had entered the Second World War. Magee would become the first to immortalise the Vickers Supermarine Spitfire in verse; and he did so in a letter home to his parents. That piece he titled ‘High Flight’ and from the opening two lines it clearly cuts straight to the marriage of form and power that lies in the Spitfire’s heart.

‘Oh, I have slipped the surly bonds of earth and danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings,’ Magee opened.

This young pilot claimed to have begun composing ‘High Flight’ at 30,000ft (9,144m) in the skies above South Wales, where he’d been stationed for training and where he received his first taste of this new machine. You don’t need to be a great student of poetry to hear in Magee’s writing his admiration for the transformative blend of design and engineering that, just forty years after the first powered flight, saw humankind at one with the air. Decades on, love for – and interest in – this aircraft has not diminished. It’s grown.

The Spitfire was the vision of talented aeronautical engineer Reginald Joseph Mitchell, who led a brilliant team of designers and engineers at seaplane manufacturer Supermarine to deliver this ground-breaking aircraft, just in time for the Second World War. The Spitfire was Mitchell’s answer to the Government’s call for a new type of mono-winged fighter aircraft to meet the growing threat posed by a rearmed Germany during the 1930s. It quickly established a reputation in the early years of the war, in particular during the Battle of Britain, which was immortalised as a metaphor for plucky survival against seemingly overwhelming odds. In this pivotal conflict, the RAF was in a backs-against-the-wall fight for the future of the homeland against the numerically superior forces of Nazi Germany’s air force, the Luftwaffe. Victory was vital, as defeat would have laid Great Britain open to invasion by the German army, which – fresh from the conquest of mainland Europe – was poised on the other side of the English Channel. Yet the RAF prevailed, and the glory of that battle reflected well on the Spitfire.

Contrary to what many will think they know about the Battle of Britain, however, Mitchell’s modern combat aircraft was not the most successful in terms of German aircraft shot down. Nor did the Spitfire dominate British squadrons: the RAF’s front ranks were dominated by the Hawker Hurricane and the pilots of the Hurricane outperformed those of the Spitfire. During the Battle of Britain, the RAF operated twenty-nine squadrons of Hurricanes versus nineteen of Spitfires, with the pilots of these fighters scoring a total of 656 and 529 kills respectively during the Battle. And yet it’s the Spitfire that is most associated with that conflict. Before the war, too, the Hurricane had pipped the Spitfire – this time making it into production first and becoming the RAF’s first mono-wing fighter aircraft.

Why then does history and national culture celebrate and revere the Spitfire and not the Hurricane? Unlike the Hurricane, the Spitfire was rooted in an earlier generation of award-winning racing planes also from Mitchell. A combination of streamlined design, use of all-metal body and a powerful Rolls-Royce engine by Mitchell paid dividends in terms of agility, stability and performance and weight. In April 1944 a Spitfire using a new-generation Rolls-Royce engine achieved a record test flight speed in a dive of 606mph (975.26kph) – just over Mach 0.8 – meaning that the Spitfire was on the road to breaking the sound barrier and entering the realm of jet-powered planes. This design and build gave Spitfire pilots a critical edge in their life-or-death fight against the best of the Luftwaffe. Little wonder, then, that the legend of the Spitfire should begin to be fostered in the place that mattered most: among the ranks of the RAF.

Wing Commander Roland Robert Stanford Tuck was one of the first RAF pilots to embrace Mitchell’s marvel. Flying a combination of Spitfires and Hurricanes, Tuck would become one of the RAF’s top-scoring fighter aces, seeing combat over the beaches of Dunkirk and in the Battle of Britain and claiming more than twenty-seven enemy aircraft before being shot down in January 1942. An experienced pilot flying Gloster Gauntlets and Gladiator biplanes before converting to the new plane, he found the Spitfire a major step change. Based on his not inconsiderable experience, Tuck branded the Spitfire ‘an aeroplane beyond all compare’.1 Such was its impression, Tuck reckoned years later that he could still find his way around the Spitfire cockpit with his eyes closed.

To fly the Spitfire was to slip the ‘surly bonds’ of earth.

Roaring to go: Spitfire of the Battle of Britain Memorial Flight.

Others echoed Tuck. Richard Hillary was an Australian pilot serving with the RAF’s 603 Squadron and assigned to the new machine. Recuperating from wounds following one particular dramatic engagement, Hillary took the time to recount his experiences in the Battle of Britain by writing his memoirs, The Last Enemy, published in 1942. It’s clear this young pilot was smitten by Mitchell’s creation. In his introduction he writes:

The Spitfires stood in two lines outside ‘A’ Flight Pilots’ room. The dull grey-brown of the camouflage could not conceal the clear-cut beauty, the wicked simplicity of their lines. I hooked up my parachute and climbed awkwardly into the low cockpit. I noticed how small was my field of vision. Kilmartin swung himself onto a wing and started to run through the instruments. I was conscious of his voice, but heard nothing of what he said. I was to fly a Spitfire. It was what I had most wanted to do through all the long dreary months of training. If I could fly a Spitfire, it would be worth it.2

Geoffrey Wellum was the youngest RAF pilot to serve in the Battle of Britain. He recalled fondly the union of power and control in the Spitfire during a 2001 interview with historian and author James Holland:

Bloody thing flew me! You didn’t get in, you strapped it to you. A Spitfire could almost think what you wanted to do and it did it. And you didn’t think anything about it. It could only respond to what you wanted it to. The Spitfire did that. It responded to anything you wanted to do.3

Those who duelled with the likes of Wellum in his Spitfire admitted a certain admiration for this foe. Adolf Galland was a decorated Luftwaffe pilot rising up the ranks in the war’s early years. By the time he encountered Spitfires, Galland had gained sufficient experience at the controls of a range of German fighters and had tangled with pilots of enough nations and their machines to recognise a worthy adversary. Galland had served with Hitler’s forces during the Spanish Civil War as part of the Condor Legion on the side of Fascist General Franco against the Republicans, and fought during the Nazi invasions of Poland in 1939 and France in 1940. Galland wasn’t simply a flyer; he was a tactician, too, and helped formulate the Luftwaffe’s battle tactics. If anybody serving with the Luftwaffe was familiar with the nuances and demands of aerial combat in a range of theatres versus a multitude of enemy pilots and planes, it was Galland.

Flushed with the successes of Poland and France but with the Battle of Britain going against them, a frustrated German High Command blamed its pilots rather than the tactics. The veteran commander Galland was flying the Luftwaffe’s leading combat aircraft by the time of the Battle of Britain – the lethal Messerschmitt Bf 109 from the formidable German aircraft designer and manufacturer Willy Messerschmitt. It was during one heated confrontation with Luftwaffe commander Herman Göring that Galland apparently conceded his admiration for the RAF’s latest fighter. During a meeting with Galland and his fellow officers, Göring had asked what it was they wanted for their squadrons. ‘I did not hesitate long,’ Galland recalls in his memoirs, The First and the Last. ‘I should like an outfit of Spitfires for my group.’ Galland claims to have been shocked at his outburst and professes to have fundamentally preferred the Luftwaffe’s Messerschmitt Bf 109. Galland’s quote has been hotly analysed since, but the damage was done. Galland recalls his boss ‘stamped off, growling as he went’.4

Success for the RAF in the Battle of Britain was a watershed moment in the course of the war. Blocked in the west, Hitler turned his attention to conquest of the east with the invasion of Russia the following year. Nobody could have known at that time, but armed with its dynamic new fighter, the young pilots of the RAF had saved Britain and while the war was far from over, the immediate risk of invasion and conquest of the homeland had passed. The fate of millions had hung on the fortunes of a few hundred in their magnificent new machines and as that battle had raged overhead Prime Minister Winston Churchill encapsulated the spirit of those months in his now famous speech of August 1940. ‘Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few,’5 Churchill told MPs and the nation.

The story of the war is, however, studded with famous weapons from all sides that found their moments, but the Spitfire succeeded where these others failed to become as embedded in the national consciousness and the cultural mainstream. The emotional connection between Spitfire and nation was tangible. People watched the skies above London and the South-East in late summer 1940 and witnessed the aerial battle unfold, craning to see first-hand the Spitfire in action. But how to account for the national passion among those without that front-row seat?

Engagement was key, and campaigns such as Spitfire Funds, a scheme that enabled people to compete in raising money to ‘buy’ a Spitfire, helped. The idea of sponsoring weapons such as aircraft pre-dated the Second World War but peaked with the Spitfire. The energetic Max Aitken, 1st Baron Beaverbrook, is credited with creating this particular scheme. Appointed Minister of Aircraft Production by Churchill in 1940, press-baron Lord Beaverbrook was the author of different public appeals through his newspapers, which included asking the housewives of Britain in July 1940 to donate their aluminium pots and pans to be melted down for Spitfires, Hurricanes, Blenheims and Wellingtons. The Ministry of Aircraft Production (MAP) had already begun receiving voluntary donations to pay for the construction of aircraft – Spitfire Funds were a way of formalising that and encouraging contributions. MAP priced the Spitfire at £5,000, although the actual price was far higher, and while you could also ‘buy’ other aircraft, a stream of favourable news coverage and the power of Beaverbrook’s press machine helped ensure it was the Spitfire people wanted. Competition to ‘own’ a Spitfire became intense, with funds created by councils, businesses, local newspapers and voluntary organisations, with children handing over pocket money and retirees surrendering their pensions. Such was the Spitfire’s fame that money rolled in from across the nation, the Commonwealth and beyond: the Nizam of Hyderabad in India donated enough for 152 Squadron to be named in his city’s honour.

Filmmakers recognised a good story when they saw one and within a year of Churchill’s Battle of Britain speech the cinematic journey that brought the Spitfire story alive for decades following the war had begun. Laying the foundations was General Film Distributors (GFD), which would become J. Arthur Rank Film and then Rank Film Distributors, known to audiences for its muscular gong man in the pre-credits sequence of its films throughout the post-war years. GFD would take Churchill’s phrase and serve it back to British audiences in black and white with a reworking of the story behind the Spitfire titled The First of the Few, starring Leslie Howard as Mitchell and David Niven as a pilot who embodies the spirit of the RAF men whose names are forever associated with the Spitfire. It’s a dramatised account of the Spitfire’s creation, from desperate arms race against the Germans with the Messerschmitt, through to first fight. A year after the film was rolled out to British audiences, US cinemas released the film simply as Spitfire.

Celluloid wizards rekindled the public’s love affair for Spitfire a decade later with the biographical film of boys-own hero Douglas Bader in Reach for the Sky. Actor Kenneth More played pipe-smoking Bader, who’d lost both legs in a flying accident but beat the odds to fight during the Battle of Britain and who ended the war as a prisoner. Bader’s aerial steed? A Spitfire. The aircraft would hit big screens in full colour with 1969’s Battle of Britain, with an all-star cast of up-and-coming theatrical blood and old hands, combining documentary style with carefully choreographed air-combat employing aircraft from the era. Years later, it was a Spitfire pilot’s timeline that helped tell the desperate story of Dunkirk in Christopher Nolan’s critically acclaimed 2017 film. Nolan’s first history film saw Tom Hardy’s Spitfire pilot engaged in a dogfight over the besieged beaches as desperate British and French soldiers below sought means of escape. The film succeeded in opening a lively debate on the Spitfire’s capabilities, specifically whether it would have been possible for a pilot to glide without power and fire the aeroplane’s machine guns as portrayed in the film.

Decades on from the Battle of Britain, and not far from where Pilot Officer John Gillespie Magee Jr would eventually be based flying Spitfires at the former RAF Wellingore, Lincolnshire, a new generation of pilots are stewarding the Spitfire’s legend. The Battle of Britain Memorial Flight (BBMF) is stationed at RAF Coningsby in Lincolnshire and operates six Spitfires, along with a small selection of other vintage aircraft from the Second World War, wowing crowds at flybys, royal events and public displays. Wing Commander Justin ‘Hells’ Helliwell, formerly a member of the Memorial Flight, is quick to recognise what made the Spitfire truly stand out. Helliwell was born and raised in a world dominated by the superior speed of the jet engine. He has served in modern, computer-aided combat craft capable of pinpoint precision and deadly accuracy, in aircraft capable of allowing a pilot to engage the enemy without seeing them – a far cry from the close-quarters combat and spiralling turns that defined the Battle of Britain. And yet, despite these advances and refinements, Helliwell feels a direct connection to his predecessors:

As a fighter pilot, the first time you fly one, you understand what the pilots of old were talking about. I flew a Mk XVI as my first Spitfire, and the moment I rolled her, I knew what they meant. The centre of gravity – it’s just pitch perfect so you can almost fly her with a finger and thumb, which is beautiful from a pilot’s point of view but as a fighter pilot I knew that was very, very important from an air-to-air combat perspective.

That the Spitfire should perform so impressively in the hands of pilots is a testament to its design and construction. This successful combination would make it a hit with the RAF and ensure continued orders for the maker, Supermarine. More than 22,000 were eventually built, making the Spitfire the fifth most produced aircraft of the Second World War. It came, too, in a staggering twenty-four variations and served in every theatre of war – Europe, North Africa and Asia.

Squadron Leader and former BBMF commander Andy ‘Milli’ Millikin highlights the importance of a design that made the Spitfire so versatile and successful:

Arguably it [the Spitfire] was one of the aeroplanes that turned the tide of the war and was extremely important during the Battle of Britain, but also – of course – an aeroplane that continued to be developed and improved. As the tech race started between us and the Germans, new modifications, weaponry and engines came out all the time and the Spitfire was constantly being updated to make sure it was at the cutting edge of technology. The rate at which the aircraft was expanded and improved was absolutely astonishing.

A new generation maintains the legacy of Supermarine’s secret Spitfire army

Squadron Leader and former Battle of Britain Memorial Flight commander Andy “Milli” Millikin: the Spitfire was one of the aeroplanes that turned the tide of the war

Pitch-perfect balance means you can almost fly a Spitfire with a finger and thumb, according to Wing Commander Justin ‘Hells’ Helliwell, formerly with BBMF.

But there is a story behind this legend – one that receives a good deal less attention. It is the story of how a secret army of civilians was mustered by the Government and Supermarine to help deliver the fighter that was revered then and is loved now, generations later. Just as the Spitfire played an integral role in the shaping of the Second World War, so this secret civilian army would play a crucial role in its delivery, building around 12,000 of the overall total. And they did so, too, not in giant industrial plants as you might expect, but in a network of secret factories tucked away in unassuming and everyday locations across the south of England.

The members of the secret army serving in these factories? As you would expect, boys too young to fight, men of retired age and women – but more women than you’d find almost anywhere in Britain’s wartime economy. Women had been mobilised en masse by a Government faced with the need for maximum industrial output to meet the demands of a wartime economy but challenged by the fact that men who’d normally fulfil demand and who’d dominated the industrial workforce had been called up. A pre-war labour surplus had been turned overnight into a shortage, and while the popular perception is of women working in munitions factories, aircraft manufacturing was insatiable in its demands. By 19436 women would make up 40 per cent of that sector’s workforce, second only to ordnance. Spitfire production specifically, however, saw even greater numbers. No records exist of how many worked in each secret factory but, on average, women broke through the national figure, comprising around 65 per cent of the workforce.

What accounted for this especially high figure? Necessity. The need for an instant workforce to quickly pick up Spitfire production following a dramatic and unique dispersal of manufacturing operations. Yes, the role of women reflected the national picture for a large numbers of workers, but complicating the Spitfire’s story was the fact that the factories had not been placed in the typical industrial locations where a ready supply of workers might be found. These factories had been deliberately moved to locations outside major cities to maintain secrecy and that made finding new workers more of a challenge. The women of this workforce therefore lived locally, having laboured in non-technical occupations such as hairdressing and retail, or served in unskilled domestic posts for the officer class or local gentry.

Building the Spitfire was no mean feat for these novices. Not only were these women thrown into the deep end of a new working experience but they were expected to quickly master the tools and techniques required to deliver this advanced fighter – and do so on a vast scale. This secret civilian army built, assembled, fitted and finished thousands upon thousands of fuselages and wings using new and demanding processes never before employed on such a scale in any one factory – never mind in many widely dispersed smaller units.

The names of funds who’d raised money for Spitfires would be painted on fuselages.

These industrial innocents were assigned to environments full of deafening noise, working twelve-hour shifts day and night, handling heavy machinery and engaged in repetitive tasks. They did so, too, with the added stresses and strains of living during wartime – facing the privations of conflict and living under the constant threat of bombing. Their novice status did, however, confer a considerable advantage: they came unencumbered by the baggage of the ‘old ways’ and found it easier to adapt to the demands placed on Supermarine to deliver Mitchell’s new fighter. Starting from scratch, these new recruits would quickly learn the ropes and take on ever-more skilled roles to advance up the ranks as team leaders. They embraced the work and the opportunity to get a crack at what, until then, had been a role dominated by men.

What this unique class of worker might have lacked in experience they made up for in potential and determination. They would exceed the wartime challenge laid before them and defy society’s expectations. Driven by a new-found spirit in their venture, the workers of the secret Spitfire factories would deliver the first Spitfire – a Mk 1A, No. R7252 – just six months after Supermarine had been bombed out and sent its operations underground, beginning again more or less from scratch. What followed that first Spitfire in March 1941 was a fleet of thousands.

Women comprised the majority of Supermarine’s secret civilian army

The women were actively recruited to join Supermarine’s secret Spitfire factories

Airframe Assemblies’ Chris Michelle: the Spitfire lent itself to the small-scale production of Supermarine’s secret factories.

It was a symbiotic relationship. Yes, Mitchell designed the Spitfire and gave the RAF its edge against a tough enemy. But his creation would have been just half the legend it has become had it not been for this unique and hidden workforce. The efforts of these workers helped guarantee the Spitfire’s status as the saviour of a nation. Helliwell muses:

Why did we do so well in the Battle of Britain and beyond? That generation was defending the homeland and the freedoms we enjoy today. So I’m guessing that those boys who were flying – and girls and boys who were supporting them – just put that little bit of extra effort and emotion into what they were doing, whether that was on the ground refuelling them, repairing them, or building them.

To fly the Spitfire was – and is – to become at one with it, and it’s easy to understand how new RAF pilots such as Magee and experienced veterans like Tuck approached this legend with a combination of awe, trepidation and relish. Understandable, too, how even the enemy admitted a grudging respect for its nemesis. But while the front-line history of the Spitfire’s success is well recorded, less familiar is the inside story of the manufacturing miracle that produced around half of those aeroplanes, founded on the work of a civilian army that toiled around the clock in hidden locations, turning Mitchell’s evolving designs into reality. Without them – and without Supermarine’s secret factories – this iconic fighter could never have achieved its dramatic or lasting impact.

This is that story.

JOHN GILLESPIE MAGEE JR:A REMARKABLE LIFE

John Gillespie Magee Jr, author of ‘High Flight’.

The Spitfire might have been British designed and built, but it was a teenage pilot from America whose poetic masterpiece helped put R.J. Mitchell’s aeroplane on the path to celebrity. John Gillespie Magee Jr was a 19-year-old serving with the Royal Canadian Airforce (RCAF) who, like so many other young Allied pilots during the war, would be captivated by the Spitfire. But, while his peers would record their feelings through memoirs, John went further, capturing the transcendental experience of flight itself realised in a Spitfire with ‘High Flight’.

John died tragically young, at the controls of a Spitfire, in circumstances that would capture the futility of war and random nature of death in conflict. His passing, however, would succeed in establishing ‘High Flight’ and thus the legend of the Spitfire. ‘High Flight’ would go on to be recited by pilots, astronauts and politicians for generations, either in honour of flight or to remember those lost in the endeavour. Such was the gentle power of this pilot’s verse that monuments would be erected in his honour and his words carved into stone, cast in metal and taken on paper into space.

‘High Flight’ was the culmination of an odyssey – a decision to quit a safe and prestigious education in the US and to serve Great Britain, where he’d studied, in the cause against Nazism. America had not yet entered the war when John joined the RCAF and was flying Spitfires, but he would die on the very day his government did declare war – 11 December 1941 – thereby making John officially among the first US casualties of the Second World War.

Born in China in 1922 to missionary parents, an American father John and a British mother Faith, it’s arguably this background towards the spiritual that found its way into John’s writing and is embodied in ‘High Flight’. Attending school initially in China, and learning different languages, John found himself at boarding school in England in the 1930s after his father sent the family abroad for safety as China became embroiled in civil war and conflict with Japan. It was through correspondence with his family while at boarding school that John became a prolific and expressive writer.

Studying at Rugby School in Warwickshire, John further developed his talents, discovering the idealistic Great War poet Rupert Brooke and proceeding to win the Rugby Poetry Prize that Brooke had won in 1905. It was during this time that Magee discovered a kinship with Britain, home to his mother, birthplace of a brother and backdrop to a network of friends and academic encouragement.

It was a fateful decision to travel to the US in the summer of 1939 for an extended break that set John on a two-year path to joining the RCAF and laid the road to ‘High Flight’. During that trip, John’s passport was inexplicably cancelled, which meant that he could not re-enter Britain. Further, John required a visa to study in Britain but his application was rejected by the US State Department just at a time when the government was concerned about maintaining its neutrality in the face of a looming war while also warning its citizens against travel to potential war zones. Marooned and finishing his education in Connecticut, Magee became convinced his place was in Britain and decided his best option for returning was to join the RAF. With the Battle of Britain raging, in August 1940 John gave up a place at the prestigious Yale University, where he was due to begin in September, and started a campaign to enlist, writing to the Canadian Government and eventually securing an RCAF interview.

John was recommended for training subject to a medical – but there was a hitch. At 6ft (1.8m) the dashing American was tall enough for duty but he was also too skinny and missed the weight requirement by 16lb (7.2kg). Determined not to fall at this first hurdle, Magee stopped smoking and binge-ate to put on the necessary weight. The regimen worked and by January 1941 John found himself on three months’ basic training on Fleet Finch and Tiger Moth biplanes at No. 9 Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS) in Ontario – today Niagara District Airport, which contains a stone monument to John. He might have been a literary 18-year-old student with no flying experience, but this period of intense training saw John quickly master the basics and gain the confidence to go solo in half the average time – 6.5 hours.

It was here that John brushed with death. Deliberately entering a vertical spin to test his recovery, he struggled to regain control and his plane corkscrewed 5,000ft (1,500m) in twenty seconds with John pulling out a few hundred feet short of the ground with one final, supreme effort. EFTS was followed by No. 2 Service Flying Training School (SFTS) learning combat and formation flying. Again, John displayed a talent but, again, death was close – thrown clear from a Harvard that he crashed while landing on a night flight. John also got into trouble: lost and landing in a remote spot, he was severely reprimanded for allowing himself to lose the way, failing to calculate the necessary level of fuel and taking too long to return to base. Fears he’d be washed out proved unfounded and John received his wings ten days after his 19th birthday on 19 June 1941. Just over a month later, John’s plan was realised and he was back in Britain.

It was in the skies above South Wales where John was sent for training in August 1941 that the young pilot conceived the poem for which he became renowned. Stationed at the RAF’s Operational Training Unit (OTU) No. 53 at Llandow in the Vale of Glamorgan, John was assigned a Mk I Spitfire that had served in the Battle of Britain and that, like many of those earlier generations of Spitfires, was being replaced by more advanced models. Flying higher and faster than ever before, John was reluctant to land and his enthusiasm got him grounded for clocking up more hours than his fellow pilots. In a censored letter to a relation, Magee gave a hint of the poem to come. ‘I could rhapsodise for pages about the [censored]. It is a thrilling and at the same time terrifying aircraft. It takes off so quickly that before you have recovered from that you are sitting pretty at 5,000 feet,’7 he wrote. Later, according to John: ‘An aeroplane is to us not a weapon of war, but a flash of silver, slanting in the skies; the hum of a deep-voiced motor; a feeling of dizziness; it is speed and ecstasy.’8