Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Westbourne Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

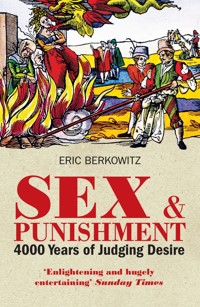

Sex and Punishment tells the story of the struggle throughout millennia to regulate the most powerful engine of human behaviour: sex. From the savage impalement of an Ancient Mesopotamian adulteress to the imprisonment of Oscar Wilde for 'gross indecency' in 1895, Eric Berkowitz evokes the entire sweep of Western sex law. The cast of Sex and Punishment is as varied as the forms taken by human desire itself: royal mistresses, gay charioteers, medieval transvestites, lonely goat-lovers, prostitutes of all stripes and London rent boys. Each of them had forbidden sex, and each was judged – and justice, as Berkowitz shows – rarely had anything to do with it.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 751

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

SEX AND PUNISHMENT

Four Thousand Years of Judging Desire

ERIC BERKOWITZ

Contents

Introduction

ONE

Channeling the Urge: The First Sex Laws

TWO

Honor among (Mostly) Men: Cases from Ancient Greece

THREE

Imperial Bedrooms: Sex and the State in Ancient Rome

FOUR

The Middle Ages: A Crowd Condemned

FIVE

Groping toward Modernity: The Early Modern Period, 1500–1700

SIX

The New World of Sexual Opportunity

SEVEN

The Eighteenth Century: Revelation and Revolution

EIGHT

The Nineteenth Century: Human Nature on Trial

Notes

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Photo credits

Index

Introduction

In 1956, in a village in Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia), a desperate woman sought help from a local tribunal made up of tribal elders in putting her marriage back on track. The relationship was in tatters. In recent months, both she and her husband had been diagnosed with a venereal disease. The husband insisted that it was she who had infected him, but she denied any infidelity and claimed he was at fault. He had threatened to stab her on one occasion and, worse, to use witchcraft against her. Yet none of that would have brought the couple to the tribunal had something more outrageous not happened, something so intolerable that the wife ran to court that very day: At dawn, she had awoken to find her husband with her breast in his mouth. She remembered his threat of witchcraft, and became terrified.

At the hearing, one of the elders demanded of the husband: “[W]hat were you thinking of when you were sucking your wife’s breast? Are you a small child, like that one [pointing to a baby in the room]? . . . Why did you do it?”

The husband’s reply only made his situation worse: “It was love,” he said.

The elder was incredulous. “Love! You must be a strange person, practicing your love in that way while your wife was asleep.” The elder and the husband went back and forth like this for a while, the husband protesting that he had merely been expressing tender affection for his wife while the elder became increasingly suspicious that the man was practicing sorcery. Finally, the elder said, “No, no . . . I am afraid that if you went with your wife, you might try to kill her.” The woman was placed in the protective custody of the police for the night, with more court proceedings to follow.

It was not the only time in mid-twentieth-century Northern Rhodesia that such disputes required court intervention. Another man had been accused of causing his wife to become infertile by sucking her breasts, and wives often ran to the courts to stop their husbands from performing cunnilingus on them or having intercourse with them while they slept. On other occasions, wives accused their husbands of stealing their menstrual cloths and using them as charms to bring success in gambling. The tribal judges took these accusations seriously. To them, taking a sleeping woman sexually was like making love to a corpse, while sucking a woman’s breasts at any time of day blurred the roles of adult and child. Cloths soaked with a woman’s menstrual blood were, in that society, not simple rags; they contained the awesome power of reproduction, which could be used for good or ill. To use such cloths for luck in gambling dens was to waste the procreative powers of the cosmos. In this context, the tribunal’s decision to post a guard to keep a breast-sucking husband away from his wife was a sensible response to an explosive situation.

The British colonial officials who reviewed the tribal decisions, however, shared none of these beliefs. They usually threw such cases out, reasoning that marital sex was the concern only of the husband and wife, for which court intervention was inappropriate. A man who enjoyed his wife’s body while she slept was simply taking the erotic pleasure that was his due, and unless he used violent force the law had no role to play. All that talk about power and witchcraft and luck was quaint, but irrelevant. Local courts in the territory complained that the Europeans should be taking these cases seriously, but their protests went unheeded.1

These incidents exist at the flashpoint between conflicting views on how the law should deal with sexual issues. To the inhabitants of Northern Rhodesia, it was not a question of prudishness, liberation, or even morality as such. Rather, sex was one of the underlying forces moving heaven and earth. Improperly conducted sex summoned danger and caused everyone harm. By barring such sex, they were protecting the entire society from catastrophe.

Lest anyone snicker at the hapless couple, we should recognize that the differences between “modern” and “primitive” views on sex and the law are not so clear—not clear enough, at any rate, to merit smugness. Sex and lawsuits have gone hand in hand everywhere, in every era, and few sexual transgressions have ever been too small to merit the meddling of one tribunal or another.

The wife in the Northern Rhodesia incident fell through a late-colonial justice gap. Her case did not fit the 1956 Western model of what a sex claim should look like. Yet had she and her husband lived in Europe a few centuries earlier, when courts regularly involved themselves in bedroom behavior, she would have found a more sympathetic hearing: European records are full of cases in which married couples were accused—and accused each other—of sexual sorcery. The judges who punished such transgressors often justified their decisions as necessary to save society from God’s wrath. Indeed, dozens of sex acts in Renaissance Europe, both within and outside marriage, were believed to provoke divine vengeance. Sexual behavior was everyone’s business because one person’s sexual missteps, if bad enough, could cause war, famine, and hails of fire and brimstone.

Moreover, had the aforementioned African couple been students, married or not, at any number of present-day U.S. colleges, the wife’s claim might well have been enthusiastically received. Many postsecondary institutions have adopted elaborate rules governing their students’ sexual conduct, which they enforce with the zeal of the most devoted officers of the Inquisition. Gettysburg College’s 2006 student handbook requires that all sex be “consensual,” which it defines as “willingly and verbally agreeing (for example, by stating ‘yes’) to engage in specific sexual conduct.” The handbook also prohibits the erotic touching of people’s bodies while they slumber. Thus, a man wishing to “initiate sexual contact” with a sleeping woman would need to wake her up, make sure her judgment is clear, and then ask (for example), “May I suck your breast now?” If he does not do so, he stands to be expelled from school and reported to the police.2

The Antioch College Sexual Offense Prevention Policy of 2006 follows a similar line, although it is more detailed. “Grinding on the dance floor is not consent for further sexual activity,” warns the policy; neither are body movements or “non-verbal responses such as moans.” Sex is forbidden with any person who is asleep, intoxicated, or suffers from “mental health conditions.”3

American university sex codes have been ridiculed as overly prudish, and college disciplinary boards mocked as kangaroo courts, but they are not going away. In fact, they recently became more accommodating forums for sexual misbehavior claims. In 2011, the U.S. government informed publicly funded universities that accusers in sex cases must win if it can be shown by a “preponderance of the evidence”—that is, a mere 51 percent likelihood—that misconduct took place, despite the fact that the question of sexual wrongdoing often turns on the murky task of defining the power relationships between the people involved. (In U.S. criminal courts, the standard of proof is “beyond a reasonable doubt.”) Duke University’s rules add to the ambiguity by stating that sexual misconduct may exist where there are “real or perceived power differentials between individuals” that “may create an unintentional atmosphere of coercion.” How anything resembling justice can be dispensed under these standards is difficult to imagine.

Regardless of the setting, no one questions the law’s primary role in resolving sexual conflicts. A person violating the shifting rules of sexual conduct in modern Western societies will not be accused of witchcraft, but that is often just a matter of terminology. Anyone, no matter how highly placed, who engages in sexual contact that is out of sync with prevailing attitudes risks being demonized and steamrolled in public by the legal system. Consider the boorish men of influence who are caught taking what they see as the perquisites of their positions. The prominent French economist and politician Dominique Strauss-Kahn’s allegedly violent sexual encounter with an African immigrant maid in a New York hotel suite in 2011 quickly became an international incident in which the limits of class privilege were much discussed, especially in France. President Bill Clinton’s dalliances with a White House intern, revealed in an unrelated sexual harassment case against him, resulted in his impeachment in 1998 by the U.S. House of Representatives (though he was acquitted by the Senate). Polish-French film director Roman Polanski, on the run since his well-publicized 1978 California conviction for having sex with a thirteen-year-old girl, again became a universal symbol of criminal sexual excess when he was arrested in 2009 by the Swiss authorities at the request of the U.S. authorities. (He was later released.) Even powerful corporations get tagged for inadvertent transgressions. The fleeting exposure of singer Janet Jackson’s breast during the 2004 Super Bowl telecast resulted in more than $500,000 in government fines against the network that aired the game, CBS, and years of wrenching litigation over sexual “decency” on the American airwaves.

With sex law, context is everything and consistency should not be expected. Under slightly different circumstances, none of these events would have sparked a controversy. Many people still cannot accept that Strauss-Kahn was chased down and jailed for allegedly forcing sex on a maid; one of his defenders dismissed the entire affair as a mere troussage de domestique (roughly, “lifting a servant’s skirt”), not worthy of too much attention. Taking the long view, this comment, while repulsive, has some logic. From the earliest times, female domestic servants have been viewed as snacks for the sexual appetites of their masters. Such women simply had no rights to their bodies, much less to be taken seriously by the police and the courts when they accused a powerful man of rape. Tellingly, the case against Strauss-Kahn was dropped after questions arose concerning his accuser’s past history, but that did not resolve the question of whether he sexually assaulted her as she described. If he did force himself on the woman, both this writer and, it is safe to assume, the readers of this book would consider him to be a monster. However, it is instructive to remember that this perspective is the historical exception.

The strobe-quick exposure of Jackson’s breast would have incurred no penalty had it been aired only on cable television or in a theatrical film, instead of during a major television broadcast. Jackson’s “wardrobe malfunction” also occurred while an ultra-conservative government was in power. (Shortly before the Super Bowl, the country’s chief law enforcement officer, Attorney General John Ashcroft, ordered that drapes be placed to hide a bare-breasted aluminum statue called Spirit of Justice, which had been standing undisturbed in the Great Hall of the Justice Department for decades.4) Bill Clinton, meanwhile, was hardly the first president to commit adultery, but he was the only one to be sued for sexual harassment, and the only one to suffer a vote of impeachment for lying about his infidelity.

Polanski’s legal timing was arguably the most unfortunate. When he had sex with the girl, statutory rape was a felony in California, and a serious one at that. Had he done the deed a century or so earlier, when California’s age of consent for sexual activity was twelve, England’s thirteen, and Delaware’s seven(!), he would have had no legal trouble. Even after the age of consent was raised, judges rarely imposed jail time on convicted men and the girls were often branded more as temptresses than victims. (It is true, however, that Polanski was not only accused of statutory rape: The girl testified that the director had drugged and intimidated her [an allegation he denied], but it is the statutory rape charge that has dogged him these past three decades.)

The existence of differing cultural mores usually has no effect on one’s risk of punishment for sex crimes. A California man recently received a 152-year prison sentence for having sex with two twelve-year-old boys. Would his legal defense have been strengthened had evidence been introduced that certain New Guinea tribes believe boys need homosexual encounters in order to mature into manhood?5 It is unlikely. In the stacks of court papers, legislation, and newspaper editorials on the subject of gay marriage, has anyone pointed to Sudanese Azande tribal traditions, which support the marriage of young boys to soldiers? Again, no. In the context of Western sex law, the customs of non-Christian cultures are irrelevant. Far from appearing overly prudish, they appear to be not prudish enough. At the same time, Western observers express outrage whenever a Muslim wife faces being stoned to death for adultery, though the Old Testament itself (Deuteronomy 22:22) prescribes the death penalty both for adulterous women and for their lovers. In early 2012, gay marriage was allowed in eight American states and the District of Columbia, while the legality of mentioning homosexuality in Tennessee’s public elementary and middle schools was being debated in that state’s legislature.

Since the earliest periods of recorded history, lawmakers have tried to set boundaries on how people take their sexual pleasures, and they have doled out a range of controls and punishments to enforce them, from the slow impalement of unfaithful wives in Mesopotamia to the sterilization of masturbators in the United States. At any given point in time, some forms of sex and sexuality have been encouraged while others have been punished without mercy. Jump forward or backward a century or two, or cross a border, and the harmless fun of one society becomes the gravest crime of another. This book aims to tell that story.

I began my research on a much broader front, trying to trace the path of Western law generally by using colorful cases as examples. As I reviewed the first legal collections from the ancient Near East, I noticed that the earliest lawmakers were preoccupied with questions of sex. Everywhere I looked, there were specific rules on sexual relations with pigs and oxen, prostitutes, family members. Sex was evidently more micromanaged then than even now, with the surprising exception of same-sex relations—which were ignored almost entirely by the law until the Hebrews labeled homosexuality a terrible crime on a par with murder. Additionally, sex was sometimes used as a punishment in itself, as when the wife of an Assyrian rapist was ordered raped in turn as punishment for her husband’s crime, or when men who damaged Egyptian property markers were required to deliver their wives and children to the rough affections of donkeys.

It soon became clear that sex law was as passionate and mercurial as the sex drive itself, and could support a rather interesting book on its own. Extraordinary flesh-and-blood cases—much flesh, more blood—jumped out of the dustiest volumes, begging to be told. Building on the work of modern historians such as Eva Cantarella (Bisexuality in the Ancient World), Sarah B. Pomeroy (Goddesses, Whores, Wives, and Slaves), and James A. Brundage (Law, Sex, and Christian Society in Medieval Europe), as well as on translations of original sources, I have mapped out the story of Western civilization from the perspective of law and libido.

The chapters organized themselves organically, according to time period. The question was when to stop. As with any era of history, no ceremony declared the end of one epoch and the beginning of another. I decided, rather arbitrarily, to halt the inquiry in the last part of the nineteenth century, with the imprisonment of Oscar Wilde for “gross indecency” with one of his young lovers. If I traveled much further into the present, I feared, the noise of our most recent century would drown out the voices of our ancestors. Today’s sex issues are touched on occasionally for perspective, but a detailed treatment of the roiling twentieth and twenty-first centuries will require another volume.

In any event, the experiences of the distant past cannot help but illuminate the issues of the present, especially where sex and the law are concerned. For example, as the issue of gay marriage lurches though the courts and legislatures of the United States and elsewhere, with all participants in the debate claiming to have history on their side, it is helpful to know that loving and committed unions between men were sanctioned by Christian and secular law alike many centuries ago, when no one recognized homosexuality as what Michel Foucault called a “hermaphroditism of the soul.” Similarly, before we rush to impose fines on television networks for broadcasting “indecent” images to the masses, it is useful to understand how obscenity fell under government control in the first place. Sexually explicit materials were never regulated until they became available to mass audiences through the advent of printing. Those who wrote and enforced the law always had access to all the smut they could digest. Finally, as we throw the likes of Strauss-Kahn and Polanski atop the trash heap of outdated boors, it helps to know how our legal and religious traditions made such sexual predators possible.

Of course, rape, adultery, incest, and all the other issues that unfold in the arena of sex law have been taking place since the beginning of human existence. All that changes are the methods people use to exercise control over one another’s bodies, and the reasons they give for using them.

ONE

Channeling the Urge: The First Sex Laws

For a four-thousand-year-old Mesopotamian homicide case, the record is impressively intact. Decades of archaeological excavations have yielded multiple copies describing the case in detail, spelled out on broken clay tablets embossed with cuneiform writing. The duplication makes sense, given that the victim was Lu-Inanna, a high priest of Enlil—one of this civilization’s most important gods—and that the murder took place in Nippur, a holy city. By the time the trial came up, Nippur had been continuously inhabited for thousands of years.

The charge was murder, although sex was all over the case. The accused were two freedmen, a male slave, and Lu-Inanna’s widow, Nin-Dada. Given the severity of the crime and the high status of the victim, the case was taken first to the king in nearby Isin. He took a good look, and then assigned it to the nine-member Assembly of Nippur.

By the time the case reached the assembly, no one doubted that Lu-Inanna had been killed by the three male suspects, nor was there any question that they had told Nin-Dada what they had done. The key remaining issue was why Nin-Dada had not immediately given up the killers to the authorities. Rather, the record says, she “opened not her mouth, covered it up.” Had she participated in the murder? If so, her execution—most likely by impalement—was a certainty. If she had not, then what crime had she committed by keeping her mouth shut?

First, a little law. In Mesopotamia, it was forbidden not to report another person’s misconduct, especially when sex was involved. (It was no different in nearby Assyria, where, for instance, prostitutes were not allowed to wear veils: If a man observed a prostitute wearing a veil and said nothing, he would be whipped, have a cord forcibly run through his ears like a horse’s bridle, and then be led around town to be ridiculed.) Mesopotamian barmaids were required to eavesdrop on their criminal customers as they drank. If the barmaids heard something incriminating and failed to report it, they could be put to death. Adultery, at least when committed by women, was also punished harshly. A disloyal wife who had plotted against her husband was treated worst of all, by being stuck on a long pole and left to suffer a slow and very public death.

There was no proof that Nin-Dada had ever had sex with any of the killers, or that she had taken part in her husband’s murder. Had she been well-represented before the assembly, she might have squeaked through the trial with her life. Her supposed advocates could not have done a worse job, however. They presented a “weak female” defense, arguing that Nin-Dada was so helpless and easily intimidated that she had had no choice but to remain mute. As if that argument were not a sure enough loser, her defenders went even further, claiming that even if she had participated in the murder, she still would have been innocent because “as a woman . . . what could she do?”

Even after four millennia and translation from a long-dead language, the anger in the assembly’s response rises from the tablets like heat:

A woman who values not her husband might know his enemy . . . He might kill her husband. He might then inform her that her husband has been killed. It is she who [as good as] killed her husband. Her guilt exceeds even that of those who [actually] kill a man. [Italics added.]

The Sumerian verb for “to know” meant the same as “to have sex,” and Nin-Dada’s silence after her husband’s murder was enough for the assembly to conclude that she was hungry for such knowledge. Far from seeing her as a weakling, the assembly made clear that she should have braved any intimidation to see that the murder was avenged. Nin-Dada was sentenced to die.

So go the brief lives and unnatural deaths of a Mesopotamian husband and wife, he murdered for unknown reasons and she for disrespecting her husband’s memory. They inhabited a world unknown to most of us, and barely understood by specialists at that.1

With the case of Nin-Dada, this chapter’s inquiry into ancient sex law begins at the time of the first known human writing. Although I shall touch on earlier periods, the absence of documentation makes the journey hazardous. In 1991, for example, hikers found a frozen five-thousand-year-old man in the Italian Alps. He had fifty-seven tattoos, still wore snowshoes, and carried a copper axe that appeared to have been of little use to him in his final moments. He was killed in some kind of violent confrontation. The corpse, now known as Ötzi the Iceman, also appeared at first not to have had a penis, which caused no end of questions (the penis was later found, looking much the worse for wear). Was he ritually mutilated, or castrated by a jealous husband? Or did his genitals, so cold and lifeless for several millennia, just shrivel away? Without additional information—that is, something we can read—it is impossible to tell whether he died at the hands of the law or whether or not sex had anything to do with his fate. While Ötzi is a relatively recent ancestor of ours, we do not know enough to arrive at any conclusions about the sexual mores according to which he and his tattoo-loving neighbors lived.

This chapter will draw on cases from as far west as Egypt, across Turkey and the Eurasian landmass to what is now Iran. Its main focus will be Mesopotamia (modern Iraq), as well as the land that now comprises Israel and the Palestinian territories. This vast region has hosted urban civilizations as complex as those of Rome, Greece, and various caliphates down to the Ottoman Empire, and as elementary as tiny bands of nomadic hunters. Its peoples spoke a multitude of languages and dialects, most of them now lost. These Sumerians, Assyrians, Babylonians, Hittites, Hebrews, and Egyptians were slaves and freemen, priests and prisoners, whores and kings, gods and witches. They mixed, intermarried, and raped each other. Everyone had a role to play in their respective societies, and was subject to punishment for bad conduct—especially when it concerned sex. Sex for some was blessed, and for others, grounds for impalement.

All ancient civilizations were intent on controlling people’s sex lives. The oldest extant written law, which hails from the early Sumerian kingdom of Ur-Nammu (circa 2100 BC), devoted quite a bit of attention to sexual matters. One of the earliest capital-punishment laws on record anywhere concerned adultery. Ur-Nammu’s Law No. 7 mandated that married women who seduced other men were to be killed; their lovers were to be let off scot-free. Death awaited virtually every other straying wife in the Near East, while the fate of her lover was often left to the husband to decide.

The first legal codes, such as that of Ur-Nammu, were founded on the customs of earlier precarious times. Even after small groups coalesced into identifiable societies, towns faced constant threat by bands of marauders looking to exploit any opportunity to invade and pillage. Adultery risked destabilizing the unity and bloodlines of a family, rendering an entire tribe or settlement that much more vulnerable. Ur-Nammu’s death penalty for adulterous women was, in this light, no innovation; it was simply the first such punishment we know about that was written down.

Ancient societies influenced each other, and the laws of one group were often adopted by its enemies and then developed further. As centuries passed, for example, the elementary sexual prohibitions of Sumerian kingdoms like Ur-Nammu evolved into the obsessively detailed rules of the Hebrews, which in turn became the foundation for the sex laws of the church and every Christian state. Until recently, the Old Testament was believed to contain the world’s first written laws. How could it be otherwise, when the Torah (the first five books of the Bible) was said to have been issued to Moses directly from God, on a mountain, amid thunder? As a product of divine revelation, the Bible could then have no predecessor, at least not one written by human beings. The 613 rules set out in the Torah were supposedly written by the same “hand” that molded the universe, and to say that the Bible drew from other societies in the Near East was to imply that God looked to pagan kings for advice.

The Hebrew claim of precedence was shattered in 1902, when French archaeologists found several large black stones in ancient Susa, Iran, which bore carved cuneiform text. When reassembled, the stones formed a single stele more than eight feet high. The writing, it was later proved, consisted of the Babylonian king Hammurabi’s 282 laws, a highly sophisticated comprehensive legal code. The stele itself was carved around 1790 BC. Further investigation revealed that the Code of Hammurabi not only predated Moses and the Torah by at least five centuries, it also dominated Near Eastern law for at least fifteen hundred years. Like Moses, moreover, Hammurabi was merely the messenger: The stele bore the declaration that the king’s laws also originated from heaven.

Several other legal codes have since been discovered (including that of Ur-Nammu), which were set down long before Hammurabi’s own time. Many of the Bible’s sex laws now look more like knockoffs of earlier regional laws than the original word of God. For example, one law, protecting men’s testicles, from Deuteronomy 25:11–12, reads:

If two men . . . are struggling together, and the wife of one comes near to deliver her husband from the hand of the one who is striking him, and puts out her hand and seizes his genitals, then you shall cut off her hand; you shall not show pity.

Did that rule really come from on high? The Hebrews might have wished to believe that Deuteronomy was the revelation of Jehovah, but the truth is much more prosaic: It was likely borrowed from the neighboring Assyrians. The laws of Middle Assyria, which date from 1450 to 1250 BC, show similar concern for testicles and an equal readiness to punish women who hurt them:

If a woman in a quarrel injures the testicle of a man, one of her fingers they shall cut off. And if a physician bind it up and the other testicle which is beside it be infected thereby, or take harm; or in a quarrel she injure the other testicle, they shall destroy both of her eyes.

The similarity of these laws is evident, though the Assyrians were no friends of the Hebrews—they conquered the Kingdom of Israel in 722 BC and exiled its inhabitants. Assuming the Torah was in fact composed by men and not dictated to Moses by the Creator of the universe, it appears that this Hebrew law was a reflection of a regional testicle fixation. There are multiple other instances of Hebrew laws overlapping with the laws of their enemies. For example, section 117 of Hammurabi’s Code holds that a man can put his family members into service as slaves in order to pay a debt, but only for three years. A nearly identical Hebrew law permits such enslavement for up to six years.

Western sex law, whether via Assyrian testicles or Hebrew whorehouses, was thus created by ancient peoples who legitimized their rule by claiming that they originated in heaven. It is easiest to work with written records such as the cuneiform tablets in Nin-Dada’s trial, but doing so can prove deceptive as well. If it could be shown that other trials had taken place in the Assembly of Nippur on similar grounds, in which the widows were let off without punishment, we would not then be able to draw the same conclusions about Babylonian society. It stands to reason that there were many, perhaps thousands, of sex trials, the records of which have been lost to history. We are forced to work only with what we have discovered, and what we are able to decipher.

There is little to be learned by separating documented ancient history from prehistory. No ceremony, solar eclipse, visit from angels, or resetting of calendars marked the “start” of history. No one, presumably, knew or cared whether the stories of their lives were being preserved for people who would remain unborn for another four millennia. Nor was there a sudden change in morality; when people first wrote down their laws, the prehistoric mind-set was still in place. The written laws of Ur-Nammu, Hammurabi, and Moses reflected the crosscurrents of long-established, illiterate societies.2

BLOOD RELATIONS AND BLOODY RELATIONS: THE FIRST SEX CRIMES

Early law thus emerged from prehistoric traditions. There is a lot of guesswork involved in determining exactly what these traditions comprised, but we can be certain that sexual impulses themselves would have been as urgently experienced then as they are today, driving people to do things with their bodies for which they were punished. For Saint Augustine, the insistent demands of the genitals were God’s curse on humanity for the sins of Adam and Eve; every sex act and thought was a new penalty for the wrongs of the first man and woman. Coming at the same subject from a different perspective, Plato also recognized humanity’s intense craving for sex, saying in his last dialogue, The Laws, that it “influences the souls of men with the most raging frenzy—the lust for the sowing of offspring that burns with the utmost violence.” For Plato, the sex drive was a mad subconscious effort to reunify humanity’s fractured nature.

Early peoples did not characterize the sex urge in those words, but they certainly felt it. They surely recognized that something had to be done to corral the “frenzy” if people were to live together in large groups. Until the sexual impulse was tamed and subordinated to common needs, civilized life would be impossible. For men, that meant trying to reconcile themselves to the mystery of the female. In primitive societies, men presumably regarded women with the same awe and terror they felt toward the natural world. Early humankind was at perennial war with nature, the forces of which were lethal as well as incomprehensible. The core of the natural world was the female womb, from which newborn human life tumbled out in a gush of blood and screams.

It was not until about 9000 BC (roughly one hundred and eighty-five thousand years after the advent of Homo sapiens sapiens, or modern humans) that the link between sexual intercourse and pregnancy was confirmed. Until then, sex and childbirth were likely too far separated in time for people to make the connection, and in any event, women spent much of their short adult lives either pregnant or lactating. Children seemed to just appear in the womb. Even more incomprehensible, and perhaps horrifying, was the blood that periodically flowed from women’s bodies. Blood was life itself, magical and dangerous to lose, yet women bled freely for days at a time with no injury, and no one knew why. The one clear fact was that menstrual blood came from women only, and from the same place where human life began.

The first sexual prohibitions could well have taken the form of Paleolithic taboos against intercourse with women during their periods. (Such rules still exist in many cultures, grounded on the supposed “unclean” nature of menstruation.) These proscriptions would have had much deeper foundations than mere hygiene, however—perhaps the sudden appearance of menstrual blood reminded men that, despite their superior physical strength, they could not generate human life on their own. Perhaps menstrual blood was considered a sign of female shame or even infertility, as women only bled when they were not pregnant or lactating. Most likely, the rejection of women while their blood flowed was a precautionary move, a way to appease the threatening divine presence men felt when confronted with the unknown.

By barring sex during specific times of the month, primitive societies could impose order onto the chaos of sex and reproduction. As time passed, men’s fear of women often evolved into outright hostility, to the effect that menstruating women were regarded as dangerous and filthy in equal parts. The belief was amplified in later centuries, in various cultures. To ancient Hindus, menstruation was a zero-sum game: Sex with women during their periods was thought to sap the “strength, the might and the vitality” of men, while avoiding sexual relations with menstruating women was believed to add to men’s wisdom and vitality. In Babylon, everything a woman touched during her period, from furniture to people, was considered contaminated, and to the later Assyrians the very word “menstruation” was synonymous with “unapproachable.”3

No one took menstrual fear further into the realm of obsession than the Hebrews. The Torah, which decrees that women and everything they touch are unclean during their periods, also pronounces that this contamination extends to things touched by people who are themselves touched by menstruating women. For example, if a man “lies” with a woman during her period and later sleeps on another bed, that bed becomes unclean. The Bible also requires that at the conclusion of a woman’s period, she is to bring two turtledoves or pigeons to a priest for sacrifice. Until the birds are slaughtered, she is to be separated from everyone in her community, including her husband. In any event, women are not to be touched for seven days following the beginning of their periods, regardless of when the bleeding stops. Later versions of Jewish law pronounced women “unclean” for about half the month, requiring them to take ritual baths before returning to their husband’s bed and mandating that wives test themselves for blood with rags before having sex. Violations of these laws subjected the man and the woman to arrest and, at least in theory, the death penalty.

Over the centuries, menstrual blood found its way into recipes for sex potions as a key ingredient. In several European cultures during the Middle Ages, mothers collected their daughters’ first menstrual flows, saving them and later mixing them into aphrodisiacs to spark desire in their sons-in-law. In fifteenth-century Venice, a lower-class girl used a mixture of her own menstrual blood, a rooster heart, wine, and flour to make a young aristocrat man “insane” with love for her. She was put to death; the young man was viewed by the court as an unwitting victim. As late as 1878, the British Medical Journal ran extensive correspondence on the question of whether or not a ham could turn rancid at the touch of a menstruating woman.4

Another prehistoric sexual taboo, which probably led to the first formal law of any kind, banned incest. While few would disagree that sex within families is repellant, the rule against it is not so simple. For most of human existence until relatively recently, there were no cities or towns, and very few people. Life was lived in tiny groups, and while interbreeding between tribes did occur, bands of several dozen people might live for extended periods without ever seeing another human being. Reproduction between close relatives must have occurred all the time. Nevertheless, without prohibitions against close inbreeding, human DNA would never have acquired the strength to adapt to the climatic and other challenges faced by our ancestors. The formation of cross-tribal societies about fifty thousand years ago allowed people to “outbreed,” diversifying their genetic makeup and making possible the most recent stages of human evolution.

Anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss regarded the incest taboo as a critical element of “culture itself,” and much of ancient history backs him up. The Babylonians treated incest as a source of contagion and punished it with banishment, drowning, or burning. Once the deed was done, the pollution had to be cleansed regardless of whether or not either of the participants was at fault. A mother raped by her son, for instance, would burn to death right alongside him. The fact that she was taken by force meant nothing; for the sake of everyone and to appease the gods, she had to die. The Hittites and Assyrians also considered incest an abomination punishable by death, as did their neighbors the Hebrews and almost every other society since then. Even monkeys avoid it.

Thus incest appears to be not only the first, but also the one universal, “natural” sexual taboo. If that were the case, though, no one told the peoples of ancient Hawaii, Peru, Mexico, and especially Egypt and Persia. For the ancient Egyptians, incest was not only a natural aspect of human life, it was also the key event in one of their most sacred and enduring creation myths: that of Isis, the mother–whore–goddess who divided earth from heaven and assigned languages to nations. Isis married her brother, the sun god Osiris, whom she adored even when they were still in their mother’s womb. Their perfect union was shattered when Osiris was murdered by his brother Set, god of darkness. Set cut Osiris into pieces, which he flung all over Egypt. Bereft, Isis searched for her beloved everywhere. She managed to retrieve every part of him except the most important one, the engine of their sacred union—his penis. Nevertheless, she resuscitated him and, with the help of a replica of his genitals, the reunited lovers produced a child, Horus. This tale, told in countless versions throughout the Mediterranean, made Isis a holy and deeply resonant symbol of renewal and immortality. During celebrations, Osiris was represented as a giant phallus.

Egyptian pharaohs often married their sisters, half-sisters, and daughters, especially during the Eighteenth Dynasty (1570–1397 BC). The idea was to exclude outsiders from the bloodline, and ensure that the bounty of conquest would not be shared with in-laws. Sometimes, as in the families of the pharaohs Seqenenre Tao II and Ahhotep I, royal daughters were only allowed to marry their fathers. However, the same restrictions never bound the pharaohs themselves: They kept a supply of secondary queens at hand with whom to have children. New kings were usually mothered by non-royal women, which sometimes made family lines quite complicated.

Egyptian incest was not restricted to the society’s upper crust; the practice was adopted by the lower orders, and became common among people of all ranks. At the time of the Roman conquest of Egypt in 30 BC, women typically married their full or half-brothers or their fathers. In the cities, one-third of all young men with marriageable sisters married them, doing away with any need to find a bride from outside the family. (In Arsinoe, virtually every man with a living younger sister married her.) The Romans shared none of the Egyptians’ incestuous customs, and worked hard to suppress them—after about three centuries, they succeeded.

In ancient Persia, marriage within immediate families was seen as a blessed thing. Under Zoroastrianism, which came into being sometime between the second millennium and the sixth century BC, royal, priestly, and common families all practiced incest. Such unions were praised in legal and religious texts as “perfect” acts that brought great rewards in heaven and wiped away nearly all sins. Said one ancient source:

[B]lessed is he who has a child of his child . . . pleasure, sweetness and joy are owing to a son that begets from a daughter of his own, who is also a brother of that same mother, and he who is born of a son and a mother is also a brother of that same father; this is much pleasure, which is a blessing of the joy . . . the family is more perfect; its nature is without vexation and gathering affection.

For the Persians, a sexual union within a family was so sanctified that the fluids produced by an incestuous couple were thought to have curative powers. A passage from the Vendidad, a collection of Zoroastrian holy texts, advises corpse-bearers that they may purify themselves with the mingled urine of a closely related married couple. Conversely, any reluctance on a man’s part to marry his sister or mother was considered a grave sin deserving of “damnation in the highest degree,” even if he troubled to find his intended bride another husband. Women who refused to marry their relatives fared even worse: In one Zoroastrian text, a visitor to hell finds a woman condemned to suffer the pain of having a snake crawl in and out of her mouth for eternity. The visitor is told: “This is the soul of that wicked woman who violated next-of-kin marriage.”

Like the Egyptians, the Persians used intra-family marriages to hoard property, but that only partly explains why such unions—so rare in the ancient and modern worlds alike—were venerated. A full understanding requires a greater degree of probing into the religious practices of these societies than this book permits, but the key point is that there are in fact no “eternal” or “natural” sex laws. What is contrary to nature for one group can be a blessing for others. The Egyptians and the Persians were not nomads or cave dwellers who had no choice but to reproduce within close family groups; theirs were two of humanity’s longest-lasting civilizations. Lévi-Strauss was surely wrong, then, to claim that the ban against incest is culture itself. Like homosexuality, fellatio, and dozens of other sex acts that have been condemned as both unnatural and against God’s will, intra-family sex was a matter of choice.

Taboos against incest and sex during menstruation have evolved in nearly opposite directions. Bans against sexual contact with women during their periods persist in some religious contexts, but have been ignored by secular law. The Talmud requires flogging for such things, but no modern Western government has given the subject any attention. Incest, however, remains a “universal taboo” and is a crime almost everywhere. It is a felony in nearly every American state, punishable by prison terms of up to twenty years. In Utah, a five-year prison sentence awaits anyone having sex even with a “half” first cousin. Many states also mandate punishments even when the incestuous sex was forced, or when, as with sexual relations between step-and adoptive relations, there is no risk of genetic harm. It is enough that such relations resemble sex within the same blood family for the offenders to be removed from society.5

VIRGIN TERRITORY

Female virginity was a commodity in the ancient world, with a price, a market, and laws to protect its male owners. Ancient Egyptians had no concern with a woman’s virginity at marriage, but that was atypical at the time. Virtually everywhere else, “a maiden who has never stripped off her clothes in her husband’s lap” or, somewhat less graphically, a woman who “has not known a man” was precious indeed—or at least her maidenhead was. The right to deflower a girl belonged to her husband and no one else, and anyone interfering with it was severely punished.

During Ur-Nammu’s reign, a man who raped a betrothed virgin was put to death. The punishment did not address the violence committed against the girl, but rather the theft of the intended bridegroom’s opportunity to be the first to have her. By the time of the Assyrians, more than a thousand years later, the laws were more intricate and, in keeping with Assyrian tradition, more vicious. Rapists of betrothed girls were killed as they always had been, but the law now also turned its attention to the rape of females who had not yet been promised in marriage. In such cases, compensation was due to a father for his lost chance at marrying his daughter off at the high price virgins commanded. He could sue the rapist and collect three times his virgin daughter’s marriage value, and then either force the rapist to marry the girl or keep her to sell off to someone else. A sullied girl would fetch a smaller bride price on the open market, but the father still came out ahead. To add a dollop of sweet revenge to the deal, Assyrian fathers in such cases also had the option of taking a rapist’s wife as a slave to rape and abuse as often as he wished. Thus two innocent women might suffer when a man raped a virgin girl: the victim herself, who might be forced by her father to spend the rest of her life with the man who had attacked her, and the rapist’s wife, who might be delivered into the vicious embrace of the victim’s family.

An Assyrian father could cash in on his daughter’s lost virginity even when she gave it away willingly. In that case, the girl’s lover would still owe the father three times her marriage value, but he would not be required to serve up his own wife for abuse. Rather, the father was encouraged to take out his anger on his daughter: “The father shall treat his daughter in whatever manner he chooses.” This sentence was perhaps legal overkill, as there were no restraints on what a father could do to his children. In any event, women were no better treated after they were married. The law was clear that a husband could punish his wife by whipping and hitting her, pulling her hair, and mutilating her ears.

The Torah tracks the Assyrian system of compensating fathers for their daughters’ lost virginity. As everywhere else in the Near East, respectable Hebrew girls had no right to choose their sex partners. Only prostitutes could do that. If a virgin girl decided to have sex with a man anyway, that choice was made permanent: Any man who slept with such a maiden was required to pay the girl’s bride price (that is, her price as a virgin) to her father, then marry her. As with the Assyrians, the father was also allowed to take the money and marry his daughter off to someone else, presumably for a lower price. The thinking changed somewhat if the maiden had been taken by force. In that case, the man was bound to pay the father a much larger sum of money and then marry the girl without the possibility of ever divorcing her. Again, the happiness of the girl was immaterial. The pain of having been raped would be compounded by having to spend the rest of her life with the assailant, subject to his will as his wife.

The laws of the Bible are less violent than those of Assyria—for example, there is no recourse to raping another man’s wife as retribution—but Biblical mythology is just as savage. The book of Genesis tells the story of Dinah, daughter of the patriarch Jacob, who “went out” from her house and then was “taken” by a neighboring prince named Shechem. The text is not clear as to whether the “taking” was the result of rape, persuasion, or something in between, but there is no doubt that Shechem fell in love with Dinah and, after installing her in his house, decided to marry her. Yet he had made a terrible mistake by not going to Dinah’s family for permission before bedding her. The disgrace he brought to Jacob’s house would need to be wiped away before anything else could take place.

Shechem and his father Hamor tried to make amends by offering Jacob any bride price he demanded, no matter how much. This offer of money would normally have been enough to assuage a family’s hurt pride and lost investment in the girl’s virginity. It seems to have been acceptable to Jacob, but not to Dinah’s brothers, whose rage could only be relieved with violence. They told Shechem and Hamor they would accept the offer of money, and then, after their enemies were lulled into a state of vulnerability, they made their attack:

Simeon and Levi, Dinah’s brothers, took their swords and attacked the unsuspecting city, killing every male. They put Hamor and his son Shechem to the sword and took Dinah from Shechem’s house and left. The sons of Jacob came upon the dead bodies and looted the city where their sister had been defiled. They seized their flocks and herds and donkeys and everything else of theirs in the city and out in the fields. They carried off all their wealth and all their women and children, taking as plunder everything in the houses. Jacob was angry when he heard what his sons had done, and also scared of reprisals, but Simon and Levi had one concern on their minds: “Should he [Shechem] have treated our sister like a prostitute?”

To Dinah’s brothers, the destruction of Shechem’s city and the murder and enslavement of its inhabitants constituted appropriate payback for their sister’s lost virginity. Dinah’s fate was not spelled out, because it did not matter. She was merely a prop in the story. The main issue at stake was the lost honor of her male family members, and what they did to regain it. Dinah’s intentions would only have entered the picture had she sneaked off with Shechem and willingly had sex with him. Luckily for her, that did not happen.

Any Hebrew man who formally accused his bride of being impure at the time of the wedding set off a high-stakes legal process. The bride’s father would have been required to prove his daughter’s virtue, which he normally did by giving the wedding bedclothes to the town elders to inspect. If the bloodstains on the fabric were deemed insufficient, the bride was stoned to death in front of her father’s house. Just as Shechem did wrong by taking what was not his, so did the sexually experienced bride commit a grave crime by deciding when, and with whom, she would have sex. (It is easy to imagine savvy fathers splattering animal blood on the bedclothes to make sure their daughters were exonerated.) If, on the other hand, the bedclothes passed inspection, then the accusing groom would be beaten by the elders, forced to pay the bride’s father one hundred silver shekels, and barred from ever seeking a divorce. Again, the bride’s emotional well-being was of least concern. She would be condemned to living out her days with a husband who most likely hated her—a small price to pay for her family’s honor.

Given the differences in marriage value between virgins and non-virgins, it was illegal everywhere even to spread rumors that a bride was something less than intact on her wedding day. The laws of Lipit-Ishtar, another Sumerian ruler (circa 1900 BC) who predated Hammurabi, required a man making such an accusation to pay a fine if proven wrong. The question is how such proof was made. The Hebrews and others used bloody bedclothes, but that was not a universal test. Neighboring cultures were not nearly as convinced that blood always resulted from a female’s first intercourse. The only way to prove conclusively that a girl had had sex was either to catch her in the act or to observe her belly swollen with child.

Why was it so critical for men to marry untouched women? It makes sense that adultery should have been forbidden, as husbands wanted to be assured that their children were actually their own, but there is no corresponding concern with marrying sexually experienced brides. If a wife gave birth less than eight or nine months after the wedding, it would have been simple enough to allow the husband to disown the child. But ancient law did not go in that direction; rather, it barricaded women and girls from sexual opportunities and punished them if they transgressed. Explanations for the virginity obsession seem to be limited to men’s desire for a “tight fit,” as well as the assurance that the human property they purchased was truly brand new. Most likely, though, the fixation on virginity—which never existed where men were concerned and has persisted to this day in many cultures—was simply one more avenue for men to control and dominate females. Having a virgin for a bride was power incarnate for a husband, and keeping her untouched before marriage was a test of control for her father and brothers.6

THE JOYS OF MARRIAGE

The sexual restrictions ancient societies placed on girls and women did not loosen with their marriages. The restraint fathers expected of their daughters was merely training for their duty of fidelity as wives. Everywhere, married women were kept on short leashes and disciplined. The Assyrian law mentioned above that allowed husbands to beat, whip, and mutilate their wives for misbehaving extended to anything short of killing them. Presumably, qualifying offenses included going about town unveiled. If only sexually available women, such as prostitutes and slaves, uncovered their heads in public, a respectable wife who did so would therefore be signaling her availability and, even worse, that her husband had lost control over her. For that, wives would suffer violence.

Married Assyrian women who kept their veils on but associated with other men were also running big risks, as were the men. Any man who “traveled” with an unrelated woman had to pay money to her husband and prove—sometimes by jumping into a swiftly flowing river and surviving—that he had not taken the woman as a sexual partner. Palace females were completely off-limits. It was a capital offense for a woman of the royal court and a man to stand together with no one else present. If another palace woman were to witness such an encounter without reporting it at once, she would be thrown into an oven.

The Code of Hammurabi made wives’ lives no less hazardous. Married women who were “not circumspect” or who shamed their husbands by disparaging them or leaving their houses without permission risked death by drowning. This penalty accomplished two purposes: It got rid of a troublesome wife and it washed away the husband’s dishonor. If a wife was so impudent as to steal her husband’s property or denigrate him in public, then he had the choice of either casting her out of his house or—in a delicious gesture of revenge—keeping her around as a slave while he remarried.

The overriding goal of these laws was to prevent even the appearance that a wife was committing adultery. Virtually nothing consumed ancient lawmakers more than female infidelity, and very few crimes were so severely punished. With the exception of the Hebrews, men who had sex outside of marriage were never at risk of punishment, but even Jewish law skewed hard against women. Married Jewish men were technically discouraged from having sex with other women, but were never punished to the same degree as their wives, and prostitution flourished in ancient Hebrew society. The men were also permitted to take multiple wives and concubines.

As a rule, women in the ancient Near East who had extramarital affairs and were caught suffered, died, or suffered and then died. That this should be the case was never questioned. The main legal issues concerned just when the punishments would be inflicted, and by whom. Could a husband go on a killing spree when he learned his wife had been unfaithful, or was the state to perform the executions? Was he allowed to forgive his wife or (less likely) her paramour? Was his decision final? As far back as the Sumerian kingdom of Eshnunna, in about 1770 BC, no forgiveness was permitted. “The day [a wife] is seized in the lap of another man, she shall die, she will not live.” Later Mesopotamian cultures allowed husbands to pardon their wayward wives and not kill them, so long as they also gave a pass to the wives’ lovers. In other cases, kings had the power to trump the husband’s decision, either by pardoning the sinning couple despite the husband’s desire to kill them or vice versa.

Assuming that punishments for adultery went forward, as they must have in most cases, they were nasty indeed—at least for the women. We have already seen how the unfortunate Nin-Dada was condemned and most likely impaled on the mere suspicion that she had committed adultery with her husband’s killers. In another case from the same period, a man named Irra-malik came home to find his wife, Ishtar-ummi, making love with another man. Rather than commit violence on the spot, Irra-malik kept his head: He tied Ishtar-ummi and her lover to the bed with rope and dragged them to the assembly for trial.

Although the case record is short on detail, it appears that the assembly took the evidence in front of them—the two lovers tied and wriggling on the bed—as proof that adultery had taken place. This would have been sufficient to seal Ishtar-ummi’s fate. Irra-malik, however, decided to pile more charges upon her. He accused her of stealing from his grain storehouse (perhaps to give a gift to her lover) and opening his jar of sesame seed oil, covering it again with a cloth to hide her theft. While these additional charges seem piddling next to adultery, they were framed as part and parcel of female wrongdoing: Bad wives not only took lovers, they also wasted their husbands’ resources.

Ishtar-ummi’s life was headed for a cruel end, but death appeared to be too much for her to hope for. The assembly first ruled that her pubic hair be shaven—whether this was merely to humiliate her or to prepare her for a lifetime of slavery, we do not know. It is probable that she was to be downgraded from wife to slave in Irra-malik’s house, to be abused daily by him and his new wives. Before that happened, however, the assembly also ruled that she was to have her nose bored through with an arrow before being led around the city in disgrace, like a mule. The fate of her lover is not recorded, although it is likely that if she was not killed, neither was he.7

Wives never had any right to complain when their husbands took lovers, except when they were refused sex altogether or belittled in public. In that case, at least in Babylon, they could attempt to divorce their husbands—but that was a risky step, for the trials inevitably covered the wives’ sexual behavior as well, and if they were found to have been promiscuous themselves they were thrown into a river to die. Given the risks involved, it was a far safer, if more bitter, decision for wives simply to put up with their husband’s misbehavior.