28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

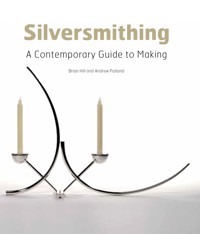

As well as promoting the traditional origins of handmaking craft skills, this lavish book explains the latest techniques and opportunities that exist for today's designer silversmith. It emphasizes the importance of acquiring fundamental skills as a basis to creating stunning and innovative designs, and illustrates this with fabulous case studies from leading silversmiths. Written by two experienced designer craftsmen, this book takes a fresh and exciting approach by converting craft theory into visual language that informs, educates and inspires you to try a new technique, extend your skills and develop your own personal direction.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 260

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Silversmithing

A Contemporary Guide to Making

Brian Hill and Andrew Putland

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2014 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2014

© Brian Hill and Andrew Putland 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 616 1

AcknowledgmentsThe authors have enjoyed the high spirit of liaison and collaboration from the industry in compiling this book. In particular we thank The Goldsmiths’ Company and The Goldsmiths’ Centre for their incredible and invaluable support. With special thanks to Eleni Bide, David Beasley, Alison Byne, Robert Organ, Rosemary Ransom Wallis, Gerry Tiling and Richard Valencia.

Live visits to workshops at The Goldsmiths’ Centre have been crucial in capturing manufacturing techniques that feature throughout the book. Our appreciation and gratitude extends to John Need, Reg Elliot, Alan Fitzpatrick, Sam Marsden and James Neville for their expert help and assistance.

The computer illustrations bridge theory and practice, generated and crafted by Richard Gamester, and we thank him for his significant contribution.

In Chapters 4 to 6 the substantial image commentary has been generously supported by photographer Lee Robinson, we thank him for his contribution.

Our thanks also go to the Goldsmiths’ Craft and Design Council for the use of some images.

Cover images

Front cover: Brett Payne, X–Y candlesticks.

Frontispiece

Silver chandeliers by Padgham and Putland, using a stainless steel skeleton. Commissioned by Prime Development Ltd and Nicola Bulgari.

CONTENTS

Introduction

1 History, hallmarking and assay

2 Materials, tools and equipment

3 Health and safety

4 Manufacturing techniques, methods and processes

5 Polishing and finishing

6 Surface decoration and decorative treatments

7 Technology in a traditional craft

8 Designers in industry

9 Designer-makers

10 The next generation

Further Information

Glossary

Index

INTRODUCTION

The unique craft of silversmithing has managed to survive the passage of time; its traditional skills, techniques and processes are still relevant for practising silversmiths in the twenty-first century. For modern silversmiths, particularly the self-employed, this is an exciting and rewarding time to be engaged in this popular area of the precious metals specialist crafts. Designers continue to demonstrate creative expression and individuality through their three-dimensional work, whether focusing on conventional, skills-based techniques or harnessing new production and technological advances. The collective outcome guarantees that there is something appealing, distinctive and attractive for everyone’s attention, appreciation and admiration.

The primary aim of this book is to inform, inspire, encourage and direct those who wish to learn more about the practical craft of silversmithing, whether they are students, enthusiasts or designers. Additionally, it can serve as a useful compendium for practising silversmiths. The book has a strong vocational and practical ethos, aimed at guiding readers through a hands-on, step-by-step approach that encourages interested parties to have a go and become experiential learners.

The book’s central remit and intention is to relay the traditional making aspects of the craft in a contemporary context, alongside the more recent technological advances. These advances offer stimulating opportunities for designers and makers to develop, increase and enhance their portfolio of skills, experience and overall capabilities.

The number and palette of designer-makers engaged in silversmithing increases year on year and the abundance of outlets for self-employed practitioners continues to grow. A high percentage of these designer-makers have taken the college/university route of training, and the book is very much addressed to this vibrant population, who will benefit from its vocational stance, practical advice and emphasis on the value of education.

The historical section highlights some important and striking examples of hand-craft and production skills employed on pieces of silverware; these leave us in awe of the skills and abilities of former craftspeople.

It is possible to engage in meaningful silversmithing within humble surroundings using a basic set of tools and equipment. The early chapters detail this starting point before moving on to more involved workshops for business, relating to established companies and the self-employed. There are many ways to make costs bearable and sustainable when setting yourself up: for example, communal group workshops are popular and economically viable. As well as the financial benefits that sharing resources provides, the supportive culture and working ethos that come with it encourage and accelerate learning in this type of community.

Of course it needs to be remembered that even with an extensive range of tools, equipment and machinery at your disposal, without the fundamental origins of skill-based learning, everything becomes harder and takes longer to achieve. It is these core and essential skills that everything else revolves around and emanates from. There is no substitute for these inherent craft skills and the resulting confidence and experience will serve you well as you develop your own interests, style, direction and subsequent career pathway.

Manufacturing techniques and methods along with production processes take centre stage in this book, to help engender skills-based learning as a basis for promoting the traditional methods of making, which remain irreplaceable. They hold the key to successful, high-quality making of a professional standard, and serve as an excellent foundation from which all other things evolve, develop, progress and prosper.

The many decorative treatments that are available to the silversmith extend a range of visual qualities to designs, offering greater levels of contrast and impact. Allied aspects of the craft, such as chasing, engraving and enamelling, are excellent examples that give form, detail, colour, refinement and enrichment. The chapter on surface decoration illustrates the significant contribution that these forms of decoration can provide on larger-scale work.

Over recent years computer aided design (CAD) has developed to a point where it is now difficult to separate the real from the virtual. This challenging and pioneering period has seen a substantial shift towards design, particularly the rendering of large-scale work, and this area of rapid progression in silversmithing is an important aspect for inclusion in the book.

For some time, rapid prototyping has been the logical extension from CAD and this is now widely used in the construction of domestic and ecclesiastical products, models and artefacts, and in some cases has revolutionized the way parts can be accurately produced. Additionally, the use of laser and TIG welding has offered positive assistance to the silversmith and this technological development needs to be recorded, utilized and celebrated widely as we seek to improve our capabilities and calibre of work.

The chapters on designers in industry and designer-makers profile an extensive and diverse range of technical processes and aesthetic styles. There is such depth and breadth of activity in silversmithing that the entire book could easily have been taken up by portraying some of the many gifted designers and their varied and beautiful work.

The concluding chapter describes a positive future from the next generation of silversmiths, and in particular highlights the vibrant, talented and diverse range of designer-makers who are embarking on their career. These are sole traders who design and manufacture a wide array of creative and appealing products, wares and objets d’art. None of these up-and-coming creative designers will say that ‘doing your own thing’ is easy or straightforward; however, they all share a common passion, belief and conviction that they are indeed fortunate to be able to design, produce and sell their own bespoke work. We believe that this creative and talented community will make a positive and significant contribution to the design movement in the twenty-first century.

Wine cooler by Scott and Smith.

CHAPTER ONE

HISTORY, HALLMARKING AND ASSAY

History – an introduction

The central objective of this section is to draw attention to some of the outstanding craftsmanship, creative and technical skills in work that has been crafted and manufactured in past generations.

There are countless fantastic pieces of silversmithing from history that can inspire, inform and educate us, and this great asset should be a constant source of inspiration and reference for any silversmith who aspires to be a designer and maker of note. To this end, and to help get a good perspective and understanding of our silversmithing roots, we have focused on a selection of historical pieces that are part of The Goldsmiths’ Company silver collection.

The writing that accompanies the images below is structured in two ways: the opening description of the pieces takes a contemporary angle and includes important and interesting details, facts and information; the main body of text focuses on a craftsman’s summary and analysis of the making, skills and craftsmanship involved in each of the specific pieces. This approach gives an unusual and welcome scrutiny, attention and focus to work that is in the excellent/outstanding category, and therefore helps us to reflect on the astonishing examples of craftsmanship that are available for us to research, admire, respect, record and measure.

The quality of work described in this chapter also needs to be placed in the context of the limited tools and equipment that were available, and the lifestyle and working conditions of craftsmen back in the early eighteenth century, although these would have improved and developed over time. They certainly didn’t have anything like the vast array of tools, equipment and technology that we have around us today, and this only serves to heighten our respect and admiration for the work they produced, the technical and artistic challenges they mastered, and the incredible standards that were attained.

In our study of these pieces there are many examples of silver gilt finishes, synonymous of the periods covered. Apart from the obvious decorative enrichment, this process also protected silver surfaces from oxidation, hence reducing the frequency of cleaning. Silver gilt is a process of applying gold by electroplating.

Monteith bowl by Edmund Pearce, 1709

Monteith bowls were developed at the end of the seventeenth century as a way of chilling glasses, important when serving fashionable cooling drinks such as punch. They were filled with iced water and early examples had simple, notched rims which held glasses upside-down by the foot so that the bowl of each glass was submerged and the glasses, which were expensive to replace, didn’t bump into each other.

George Ravenscroft invented lead glass at the end of the seventeenth century. Glasses were expensive and were washed during meals to be re-used because of their value. By the beginning of the eighteenth century the rims of these bowls had become highly decorative, like this example, which features ornate scrolls, dolphins and satyr masks. The fluting found on the body of this Monteith bowl is also typical. The technique would not only have been easier to carry out in the softer Britannia silver, the standard that was compulsory between 1697 and 1720, but would also have made the bowls stronger. According to a contemporary writer, the name ‘Monteith’ comes from ‘a fantastical Scot called “Monsieur Monteigh” who wore a cloak with scalloped edges’. His fame didn’t last, but the bowls remained popular into the 1720s.

Monteith bowl by Edmund Pearce, 1709. Size: Height 28cm × Width 37cm (H 11" × 14.5"); Weight: 4,227gms (136 troy oz).

Monteith bowl (detail).

This Monteith bowl shows some fine skills, ultimate control and incredible detail through carefully crafted chasing work, transforming the hand-hammered generic bowl into a refined, more delicate and attractive piece of silverware. The hallmark of hand hammerwork is in plentiful supply on this piece and such control and execution allows you to easily see and appreciate this lovely work. Because of its design, the craftsman’s work is also apparent on the inside of the bowl, therefore increasing the aesthetics and visual power of the piece.

The chasing sections on the rim of the bowl have been crafted separately and then applied; not only do these decorative additions beautifully complement and balance the design, they also contribute to the strength of the rim and support the drinking glasses that would be positioned around it. The strength of the rim was important in this instance because it is a detachable section and consequently more prone to damage and abuse. Without the decorative rim in place the vessel can be used as an ordinary bowl and therefore serve a number of different functions. The base detail has been chased and modelled, the pattern providing both strength and authority to the piece but also lightly reflecting up into the main body of the bowl, offering greater visual qualities of reflective illusion to the piece.

The handles were modelled, probably in wood, and sand cast in two sections. Light chasing, almost mimicking that of engraved cut lines, is also present above the main body flutes and allows the stronger detail to blend and fade into the bowl’s body.

The Monteith bowl is a marvellous example of how applied decoration can contribute positively to the visual, aesthetic and structural qualities of large-scale silversmithing, with the added value of seeing this detail on both the inside and outside of the design. The modelling, light chasing/repoussé work and engraving give further refinement and these aspects collectively make this strong bowl more attractive, desirable and appealing.

Chocolate pot by Joseph Ward, 1719. Size: Height 30cm × Width 18cm (H 12” × 7”); Weight: 1,514gms (49 troy oz).

Chocolate pot by Joseph Ward, 1719

Drinking chocolate arrived in England in the mid-seventeenth century, around the same time as two other exotic hot drinks, tea and coffee. It was the most expensive of the three beverages, and the most complicated to make. Early recipes call for chocolate ‘cakes’ from the Americas to be ground up with other ingredients like milk, claret, vanilla and eggs. The vessels that were developed to hold this elegant drink often had a hinged finial on the lid which allowed a rod to be inserted to stir the mixture. By the early eighteenth century both chocolate and coffee pots were tall and tapering in form. This example follows what is sometimes known as the ‘geometric style’, popular in England between the 1680s and 1730s. The octagonal section complements the function of the pot perfectly: the angles are not so sharp that they become susceptible to damage, and the number of sides means that the spout and handle can be placed opposite each other.

The clean lines and an uncluttered appearance of this domestic and very functional piece from the early eighteenth century disguise how demanding it is to construct such a design. This type of domestic silverware calls for a very different set of skills compared to hand raising and chasing, for example. The main body would have started life as a seamed and tapered cone before the very difficult task of hammering it into its octagonal section was begun, and this task alone requires a great deal of skill, experience and capability in a craftsman. Quite apart from the accuracy needed to shape this into eight equal sides, the degree of difficulty in manufacturing this design remains ever-present at each and every stage of construction.

Processes and techniques deployed would have included: stake and template making, accurate marking, mitre work, forming and box making, fitting wires and handles, hinges and soldered assemblies. The spout has been modelled and cast in two sections and the hinge of the main lid boasts a safety chain attached to the rivet pin, even though the lid can open fully for washing and cleaning. The secondary lid is also hinged to enable access and storage of the stirring stick.

This design relies heavily on high-quality making; craftsmanship is paramount. Allied to this are the aesthetic qualities that this striking and exacting piece of silverware exudes if made as it should be. The design is a masterpiece of its period and style; it also looks – and probably still is – a very functional and successful domestic product from the eighteenth century.

Water fountain by Peter Archambo, c. 1728 (later hallmarked 1929)

Made by the silversmith Peter Archambo for George Booth, 2nd Earl of Warrington, this substantial piece of silver would have played an important part in aristocratic dining. It was intended for the sideboard at the Earl’s country seat of Dunham Massey, and sat alongside a variety of other silver, to be viewed and admired as the height of the fashionable baroque style by his dining companions. Fountains like this one contained water to rinse glasses – the wine itself was kept chilled in a massive silver cistern which stood nearby. The design of the fountain reflects the early-eighteenth-century emphasis on imposing forms, with the decoration playing a supporting role. The handles are mounted on two rampant boars, the Warrington supporters from the Earl’s coat of arms, whilst the cover features an Earl’s coronet.

Water fountain by Peter Archambo, c. 1728 (later hallmarked 1929). Size: Height 71cm × Width 47cm × Base 30cm (H 28” × 18.5” × 12”); Weight: 17,884gms (575 troy oz).

It weighs an impressive 575oz, which helps to explain why it originally had fraudulent hallmarks: Archambo, to avoid paying the high tax of sixpence per ounce which was imposed on silver at that time, submitted a small waiter (a tray, salver or plate) to the Assay Office for marking. This was let in afterwards as the base of the fountain. In order to be sold at auction in 1929 it was sent in to the London Assay Office to be fully tested and hallmarked according to that date.

The substantial structure, form and size of this fountain positively contributes to its majestic statement of strength, power and authority. This significant piece depicts two main skills: the demands of the silversmith through excellent control and forming by hammering on all the component parts of this striking vessel; and the substantial array of chasing and artistic detail that adorn and beautifully decorate this iconic eighteenth-century design. The majority of the ornate detail is modelled, chased and then applied to the fountain. Three-dimensional modelling skills have also been most effectively deployed on the cast hollow animal handles and functional tap/s.

Water fountain (detail).

The hammering, forming and shaping of this vessel would require a highly experienced silversmith to produce such bold, definite and exacting shapes; and much time, application and experience were needed to manufacture this type of work to such a high standard of execution. On studying the magnificent chasing and modelling, it could be argued that the skill and artistry invested by a modeller/chaser on this fountain would equal that of the smith who created the main form and structure. Wherever you look, it is worth scrutinizing the chasing and modelling work: it is simply exquisite and breathtakingly beautiful. The feel, control and execution of detail, the precision in relief work, and the artistic portrayal are top class. The modelling of the wild boar for the handles matches the overall standard, and the higher-profile chasing on the figureheads is another fine example of the work of craftsmen at the top of their trade. The whole piece therefore sets a great benchmark for us to aspire to, and exemplifies an early-eighteenth-century workshop employing skilled craftsmen in a number of disciplines under the direction of leading Huguenot silversmith, Peter (Pierre) Archambo.

Sideboard dish by Paul de Lamerie, 1740/41

Most large pieces of silver are made to impress, but this dish, elaborate, huge in size and richly gilded was created as a celebration of the prestige and wealth of one of goldsmithing’s most important institutions. It was made in the workshop of Paul de Lamerie, the most famous silversmith of the eighteenth century, and is regarded as an important example of rococo design.

The son of refugees who fled religious persecution in France, de Lamerie showed early talent as a craftsman and businessman, and rose to become a senior member of The Goldsmiths’ Company (despite a sometimes alarming disregard for its rules). In 1740 The Goldsmiths’ Company commissioned him to make new items of plate commemorating gifts of silver which had been sold for cash during the hard times of the previous century. With a 6-inch border featuring exuberant rococo decoration and a large coat of arms at the centre, the dish embodies the Company’s confidence and return to fortune. Senior members thought it was ‘performed in a very curious and beautiful manner’, and didn’t even mention that it cost considerably more than de Lamerie’s initial quotation.

This masterpiece demonstrates the ultimate skills and artistry of the silversmith where the main techniques of sinking, modelling and chasing have been beautifully exercised and interpreted on this large-scale iconic piece. Cut card, modelling, surface decoration, pre-chased and applied sections, all contribute to a stunning effect and visual statement. Apart from the skill demands, the sheer size of this dish (nearly a metre in diameter) and the volume of the work involved meant that this substantial dish would have tested the very best of craftsmen for endurance, concentration and sustained application throughout its manufacture.

The majority of the chasing on the outer circle surrounding the centre dish has been chased on the actual dish itself with some higher-profile sections chased and modelled independently and brought on. Other areas would have been modelled, cast and lightly chased and subsequently applied to the dish. The height, depth and dimensional nature of chasing on the central feature, the Goldsmiths’ Company coat of arms, is quite breathtaking and the images selected capture this amazing work for all to marvel at and to admire the artistry, the bold and expressive form, and the overall craftsmanship.

Sideboard dish by Paul de Lamerie, 1740/41. Size: Diameter 85cm × (D 33.5”); Weight: 11,960gms (384 troy oz).

Silver gilt ewer and dish by Paul de Lamerie.

The degree of technical difficulty, the scale of the work and the quality of craftsmanship achieved on this and similar pieces of de Lamerie, leave no doubt that he was a master silversmith from the eighteenth century

Ewer by Paul de Lamerie, 1740/41

Before the spread of the table fork, ewers and dishes or basins had a practical purpose in formal dining. Scented water was poured from the ewer over the hands and collected in a dish below, allowing guests to wash their hands at the table. By the time this example was commissioned, however, it was no longer considered polite to eat with one’s fingers, and such objects were used to decorate buffets and sideboards, becoming larger and more elaborate in the process.

The upturned helmet-shape of this ewer is European in origin; it shows how new, fashionable designs were brought to London by refugee goldsmiths like de Lamerie. Its decoration follows a marine theme, appropriate for a water vessel. On the lower part of the body a winged mermaid swims alongside small tritons (sea messengers) blowing conch shells, while the handle takes the form of a gigantic marine god.

Silver gilt ewer by Paul de Lamerie.

In its highly detailed and extensive craftsmanship, which comprehensively covers this dynamic ewer from top to bottom, this is yet another great piece from the de Lamerie stable. The bold, assertive, rich and lavish use of decoration is a fine example of rococo design; the smithing, modelling and chasing applied to this piece takes on a majestic and somewhat Herculean dimension through its strength, power and aura.

The ewer itself is very heavy and immediately indicates that practicality and function were not a high priority when it was designed and made. This showpiece is not easy to lift, handle and use, but what immediately strikes you is its visual power, authority and command. The main body was probably made in two sections and a high percentage of the modelling and chasing were crafted independently and then brought onto the vessel. The substantial handle, which tends to dominate your attention as a main feature, would have been modelled and cast in sections, and the weight and positioning of this alone has obvious balance and stability issues. However, this has been resolved by incorporating some counter-balancing from a clever three-pointed base unit that has also been sand cast, with applied modelled/chased sections added at a later stage. The base design, size and proportions have been carefully considered: the weight from this well-proportioned base enables the vessel to defy the laws of gravity, as it should tip over when being displayed, positioned or put to use as a functional vessel.

Ewer by Paul de Lamerie (detail). Size: Height 49cm × Width 42cm (H 19” × 16.5”); Weight: 5,849gms (188 troy oz).

Collectively, the detail, enrichment and ornate decoration is stunning in this fine example from its period, demonstrating excellent craftsmanship and showing how powerful and dynamic silverware had become in the eighteenth century. Even if you don’t personally like the work and distinctive style from this very expressive period, it is difficult not to acknowledge, respect and admire the substantial contribution, creative and technical achievement that this type of design and craftsmanship generated; they are significant and powerful statements.

Sweetmeat basket by William Plummer, 1759

The maker of this basket, William Plummer, seems to have specialized in producing pierced, saw-cut objects. A fairly high number have survived, suggesting he had a large and productive workshop, skilled in these particular techniques.The elaborate design of the basket shows the influence of the rococo style, which placed an emphasis on fantasy and detail. It was probably used to contain sweetmeats, the name given to food served in the final, sweet course of a meal. Sweetmeats were often the most visually impressive (and expensive) part of a meal, which meant the vessels used to serve them could be correspondingly flamboyant. This basket was once part of an epergne, an elaborate centrepiece with multiple branches holding small containers for different delicacies.

Sweetmeat basket by William Plummer, 1759. Size: Height 12cm × Width 14cm (H 5” × 5.5”); Weight: 196gms (6 troy oz).

Sweetmeat basket (detail).

This small, delicate and beautifully proportioned sweetmeat basket would grace any setting or occasion and perfectly illustrates how extensive pierced decoration can make a vessel look attractive – so open and lightweight – yet retain sufficient strength from its original formed structure. To achieve this balance a craftsman needs to acquire a good understanding of the structure and strength of the main shape before removing a high percentage of the surface area through piercing to achieve this type of detail, pattern and the open effect.

Quite apart from the core smithing techniques of hammering and additional ribbed chasing to create the form and main body of this basket, the applied and pierced detail transforms the piece into an open-structured and lightweight vessel, establishing its own identity and lavish style. The applied sections make a significant contribution to the appearance and strength of the basket where forming, piercing and modelling have all contributed to the base, lip and handle sections of the vessel. These parts would have been taken through to reproduce in quantity by creating master patterns for casting; the reproductions were then applied by soldering or riveting. William Plummer’s basket, as in other silversmithing examples that we have used in this chapter, is a good demonstration of the considerable effect and striking impact of these decorative techniques, giving vitality and eye-catching appeal to a piece of silverware. Adding sweetmeats to this adorable piece further enhances its visual impact and attractiveness; it is difficult to imagine how anyone would not warm to this lovely style and popular decorative piece of petite silverware.

Teapot by Michael Plummer, 1787

Whilst coffee was preferred in Europe and America by the close of the eighteenth century, the British were drinking on average more than a pound of tea each per year. Manufacturers responded to this popularity by producing a profusion of tea paraphernalia, the most important piece of equipment being the teapot. The tapering facets of this example are unusual, but not unique. In contrast to the more common cylindrical teapots of the late eighteenth century, its form is inspired by ancient vases, reflecting the prevailing neo-classical style. The wooden handle and ivory finial would have made the teapot easier to handle and use when filled with hot liquid.

Teapot by Michael Plummer, 1787. Size: Height 16cm × Width 26cm (H 6.5” × 10”); Weight: 513gms (16 troy oz).

Teapot (detail), showing the applied engraving and light carving on the panels of the main body.

Whichever way one analyzes the manufacturing techniques deployed on this elegant piece of silversmithing, it shows an impressive combination of production techniques deployed at the time of the Industrial Revolution, supported by handcraft skills, to form, fit and assemble this sophisticated and complex construction.

The confidence and experience needed to manipulate forms by stamping, forming and hammering would have been a fair test for the craftsmen and engineering ingenuity of the time. But clearly these skills were refined, developed, mastered and delivered in this oval-sectioned teapot.

The deeply ribbed detail on the main body extended the requirement of processes and techniques to take silver into such deep sections and in multiple positions. This would have tested the metal’s malleability and craftsmen’s skill in taking sheet metal across three different form directions. Here was a real examination of what could be achieved in form, line and direction in search of stylish yet functional products.

The main body would have been made up in two separate sections because otherwise the metal would not have been able to tolerate such extremes of depth and force, but this method and approach then generates incredibly difficult fitting requirements when bringing these sections together in assembly and preparation for soldering.

To varying degrees the spout, handle sockets and base of the teapot are all technically demanding and collectively this piece shows a wide range of processes, techniques of production and hand skills, including stamping, forming, hammering, fitting, assembly and soldering of component parts.

Applied engraving and light carving on the panels of the main body, circumference and centre section of the lid give added value to the refinement and sophisticated ethos of the design. It is possible that some of this fine detail could also have been achieved by light chasing but there is insufficient evidence on this example. Quite apart from the range of its technical attributes, the design appears to answer all the practical requirements of stability, pouring, handling and insulation; in short a fine example where all the important criteria seem to have been answered extremely well.

The flush hinge on the teapot lid is beautifully hand crafted and integrates so well on the piece it is hardly noticed as the decorative engraving flows around this area. The base of the teapot is also a good example of production, hand-fitting and assembly techniques. The ribbed detail around its circumference perfectly complements the intense detail on the main body and the remaining generic form of the base provides a welcome and effective contrast on the vessel as it mirrors the same aesthetic on the lid of the teapot.