7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: McNidder and Grace

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

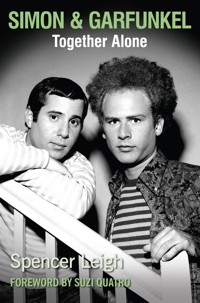

SIMON & GARFUNKEL is a definitive account of Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel's career together. With unique material and exclusive interviews with fellow musicians, promoters and friends, acclaimed author Spencer Leigh has written a compelling biography of some of the world's biggest musical stars. With remarkable stories about the duo on every page, the book not only charts their rise to success and the years of their fame, but analyses the personalities of the two men and the ups and downs of their often fraught relationship.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 467

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

SIMON & GARFUNKEL

Together Alone

Spencer Leigh

‘Simon and Garfunkel were a team.

I always knew that.

I’m not so sure Paul did.’

Art Garfunkel, 1998

Acknowlegments

My thanks to Ben Coker, David Charters, Fred Dellar, Andrew Doble, Peter Grant, Patrick Humphries, Mick O’Toole and Sue Place. Thanks to the various music magazines of the day including Disc, Melody Maker, New Musical Express (NME) and Record Mirror. I’m very grateful to Andy Peden Smith for suggesting that my 1973 book Paul Simon: Now and Then should be updated – and here it is, eventually rewritten. Love as always to my wife, Anne – we met through the first edition of this book in 1973 and are still together.

Contents

Foreword by Suzi Quatro

Preface New Books For Old

Chapter 1 Born at the Right Time

Chapter 2 Hello Darkness, My Old Friend

Chapter 3 To England Where My Heart Lies

Chapter 4 Blues Run the Game

Chapter 5 1966 and All That…

Chapter 6 Graduation Day

Chapter 7 See How They Shine

Chapter 8 Everything Put Together Falls Apart

Chapter 9 Give Us Those Nice Bright Colours

Chapter 10 Still Crazy

Chapter 11 Trick or Treat

Chapter 12 The Days of Miracle and Wonder

Chapter 13 Lefty or Left Behind?

Chapter 14 The Capeman

Chapter 15 Simon and…

Chapter 16 Surprises

Chapter 17 The Fighter Still Remains

Bibliography

Discography

Index

Suzi Quatro

Foreword

Simon & Garfunkel, wow... Immediate vivid memories of being fourteen, trying to find out who I am, and discovering this wonderfully unique duo who somehow spoke to me. I was hooked with ‘The Sound of Silence’, but the one that really reached in and spoke to me was ‘I Am a Rock’. I had just started my own career in my first all-girl band, and was feeling like a misunderstood artist. Funny, I still feel like that now even after fifty-two years in the business! Simon & Garfunkel gave me a lifeline.

Being a singer/songwriter/musician, I dive deep into the artists that I like, so that I know every single breath on every single record. As I did with Dylan, another big love of mine. For me, Simon & Garfunkel are the melodious part of the same genre.

For some years after the Everly Brothers happened, there was not another harmony match that was so perfect, and then along came these two guys. Their voices fit perfectly together, and Art’s high notes made some of the poignant messages in the songs a little bit easier for me to take, being a highly sensitive teenager.

Their version of ‘Silent Night’ crossed with a news bulletin was a brilliant idea… Say no more!

Simon & Garfunkel have been a huge part of the soundtrack of my life. Thank you for the music, boys, and I have enjoyed reading about you. Your story here has been told with sensitivity and accuracy, as is Spencer’s book I am reading on Frank Sinatra.

With love and respect,

Preface

New Books For Old

In 1973 I wrote Paul Simon: Now and Then, published by a small Liverpool-based company, Raven Books. It sold 8,000 copies but was not reprinted or kept up-to-date. Copies of it now are sold at silly prices, possibly because Paul Simon completists want it and because it is an early example of rock biography.

As I kept getting emails about it, I wondered if it could be reissued as an eBook. When I read the text for the first time in thirty years, it wasn’t as bad as I suspected but it contained some dodgy opinions. Writing about ‘Mother and Child Reunion’, I dismissed the whole of reggae music, which surprised me as I thought I had loved reggae from the word go. There were mistakes – I had followed an item in the New Musical Express which said that Paul Simon and Carly Simon were related when they weren’t. There was little first-hand research and outside of a few British folkies, I hadn’t spoken to anyone.

Its big plus was that I had gone through the British musical press and found numerous interviews with Simon and Garfunkel and so I had their thoughts on most matters.

So, yes, this is the reissued Paul Simon: Now and Then, but only marginally so. Simon & Garfunkel: Together Alone is much more a new book than an old one. Mostly this is a chronological telling of the story of Simon and Garfunkel, both together and alone. As I was writing (or rewriting) it, it did strike me that there are themes that could be separate studies. I’ve done my best with their early years around the Brill Building but it would need their commitment to sort out their full involvement with the pop singles of the late 50s and early 60s; then there is their deep affection for the Everly Brothers and the fact they have sung so much of Songs Our Daddy Taught Us; there is Simon’s on-off relationship with Bob Dylan which is far more ‘on’ than most people imagine; the strong Christian imagery in Simon & Garfunkel’s songs and choice of material throughout the whole fifty years, much more than references to Judaism. A book could be written on the artists who have covered Paul Simon’s songs and how they have treated them.

It has been great to spend time with their recordings. Phrases from their songs pop into my head all the time and ‘American Tune’ seems to be on repeat in my head. Their songs work on so many levels and even when the meanings are not clear, they still sound stunning.

Early on, Simon and Garfunkel realised two things. Firstly, the world liked them working together. Secondly, they didn’t.

Spencer Leigh

July 2016

CHAPTER 1

Born at the Right Time

Although this book is largely propelled by the differences between Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel, and it would be a weaker story without that tension, they do have much in common.

They were born within a few miles and a few weeks of each other. Paul Frederic Simon was born on 13 October 1941 in Newark, New Jersey. The family tree goes back to Romania and includes tailors and shopkeepers, hence Simon’s reference to a previous lifetime in his song, ‘Fakin’ It’.

Simon’s grandfather was a cantor and his mother regularly attended services, ensuring that her son had a bar mitzvah. Simon’s parents nicknamed him ‘Cardozo’ after a Supreme Court judge, Benjamin Cardozo, who never smiled. Indeed, Art Garfunkel recalls that his stern persona made him a great poker player at school.

Paul McCartney once said to Paul Simon, ‘How come there are so many Christian references in your songs when you were brought up Jewish?’ It was a good observation: you can tell from Bob Dylan’s songs that he is Jewish but Simon’s songs are more likely to include Christian imagery.

Arthur Ira Garfunkel was born on 5 November 1941 in New York City, so they had Ellis Island and the Statue of Liberty between them. Right from the start, he looked distinctive. Look at the childhood photo of him playing baseball on his Lefty LP and you’ll know it couldn’t be anybody else.

The two families did not know each other but Simon’s family was to move east to Forest Hills, part of the Queens district. The area is famed for its tennis club and concert stadium complex and playing at Forest Hills would be Simon and Garfunkel’s homecoming gig. The horseshoe stadium, designed that way for major tennis tournaments, could seat 16,000 so homecoming gigs were lavish affairs. The Beatles played there in August 1964.

Paul’s father, Lou, was ‘the family bass man’ as he played in various dance bands, while Paul’s mother, Belle, was a schoolteacher. Lou played on The Garry Moore Show and Arthur Godfrey and His Friends. He was a bandleader too, but during the 1970s he switched to teaching and obtained a doctorate in linguistics.

Paul’s brother, Eddie, was born on 14 December 1945. He now administers Paul’s publishing and is his co-manager but he is a competent musician in his own right, and in both stature and looks he resembles his brother. In their publishing office in the Brill Building, they display their father’s double bass.

Garfunkel was raised in Kew Gardens, known then as the Jewish section of Queens. His father, Jack, sold containers and packaging, sometimes marketing his own products. His mother, Rose, was a secretary. They had three sons – Jules, Arthur and Jerry – with a total of seven years between them. Garfunkel’s earliest musical memory is hearing Enrico Caruso and Mario Ancona sing the duet from The Pearl Fishers: ‘I was five years old and already I knew that I loved melody and the drama of high notes.’

Forest Hills and Kew Gardens were neighbouring sections, both reasonably affluent, and Paul and Art lived within walking distance of each other. They both attended Public School 164 in Queens, where Belle Simon was teaching. They moved on to Forest Hills High School. They were good students and Simon was a promising right fielder on the baseball pitch.

When Paul saw Art singing ‘Too Young’ at a school assembly, he realised that performing in public was a key to popularity. Art’s repertoire included ‘I Dream of Jeannie with the Light Brown Hair’ and ‘Winter Wonderland’ and he had dreams of being a cantor, the lead singer in a synagogue.

In view of many UK connections in this book, it is apt that their first appearance together, back in 1953, was in something quintessentially British, a school production of Alice in Wonderland with Art as the Cheshire Cat and Paul, most appropriately, as the White Rabbit, the animal who is always running late. Fifty years later, Paul told stadium audiences on their reunion tour, ‘I was the White Rabbit, a leading role, and Artie was the Cheshire Cat, a supporting role.’ The implication didn’t need spelling out.

Garfunkel once remarked that George Harrison had said to him, ‘My Paul is to me what your Paul is to you.’ Garfunkel commented, ‘He meant that psychologically they had the same effect on us. The Pauls sidelined us.’

At school, Paul and Art became friends with Paul liking Art’s sense of humour but being wary of his fastidiousness. Every step is neatly planned with Art Garfunkel making lists of things to do and crossing them off as they are completed.

Art told The New Yorker about their schooldays: ‘Neither of us were the group types, except maybe in athletics. I guess we were drawn together. Being outsiders, in a sense, was one reason. Mutual interests, music among them, was another.’ In 2015, Garfunkel said that he had felt sorry for Paul because he was small.

In 1953, when Paul Simon was twelve, he and his father were listening to the radio, waiting for the commentary on a New York Yankees game. The current show, Make Believe Ballroom, featured middle-of-the-road music but the host, Martin Block, was about to play the worst thing he said he had ever heard. The record was ‘Gee’ by the Crows, a lively doo-wop record which, fair enough, would be nonsensical to the unconverted. Paul Simon recalled, ‘This was the first thing I had heard on the Make Believe Ballroom that I liked.’

There’s no definitive answer to the question, ‘What was the first rock’n’roll record?’ but ‘Gee’ is a contender. Soon Paul was trying to find the new music on the stations he could pick up in New York. Although Jewish, he thought there was nothing incongruous about listening to gospel music on Sundays and he acquired a taste for southern country music, loving the wit of ‘In the Jailhouse Now’, a country hit for Webb Pierce in 1955. Artie felt the same way and, once homework was done, they would listen to Alan Freed’s nightly shows on WINS. He was the DJ who had named the new music, rock’n’roll.

In 1955 Paul and Artie teamed up for a high school dance where they sang a rhythm and blues hit, Big Joe Turner’s ‘Flip, Flop and Fly’. Paul knew Al Kooper, a musician who features in Bob Dylan’s career, and Paul and Al ambitiously tackled ‘Stardust’ as well as rock’n’roll favourites.

Garfunkel became obsessed with the Billboard Hot 100. He’d watch how the records climbed and fell out of favour. Paul preferred playing the new music. He has often said, ‘I started playing the guitar at thirteen because of Elvis Presley’, and Elvis Presley is a recurring motif in his life.

Simon discovered that a young schoolboy could not mimic Elvis Presley’s sexuality without derision. He loved the backbeat in Chuck Berry’s songs and his constant theme of what would happen when school was out. He said, ‘I single out Chuck Berry because it was the first time that I heard words flowing in an absolutely effortless way. He had very powerful imagery in his songs and “Maybelline” is one of my favourites.’

Paul Simon loved the Penguins’ ‘Earth Angel’: he had learnt about oxymorons in English class and he had found one in a rock’n’roll song title. On one level he is right, but angels on earth pop up (or down) all the time in the Bible.

Although Simon acknowledged his debt to Chuck Berry and Elvis Presley, he teamed up with Garfunkel to produce a sound more akin to the Everly Brothers. Paul recalled first hearing ‘Bye Bye Love’: ‘I called up Artie and I said, “I’ve just heard this great record. Let’s go out and buy it.” Artie and I used to practise singing like the Everly Brothers. To me, it was weird that a group would have that name. There was nobody named Everly in Forest Hills. Everybody’s name was Steinberg, Schwartz or Weinstein. I can imagine how odd it was for the rest of the country when a group came along called Simon & Garfunkel.’

Art Garfunkel said, ‘Don and Phil are not praised enough. As much as we think they’re gods, they’re higher than gods. To me they beat Elvis. We learned from them and we outstripped them, but then they didn’t have the songs of Paul Simon.’

The Everly Brothers sounded new but their sound emanated from Kentucky and Tennessee. The Everlys took their lead from southern country groups like the Delmore Brothers and the Blue Sky Boys, but they sang faster and addressed teenage preoccupations. Nearly all the Everly Brothers records of the 1950s are wonderful: even when the song is lightweight, it is rescued by magical harmonies.

During 1957, the fledgling duo sang at neighbourhood dances and Paul recalled that ‘New York was a great rock’n’roll place in those days.’ Even at this level, they knew that Simon & Garfunkel was not a cool name. They adopted the cat-and-mouse pseudonym of Tom and Jerry, marginally better than Tweety and Sylvester. Art was Tom Graph, so named because he studied mathematics, and Paul was Jerry Landis, simply because he was dating Sue Landis.

Paul said, ‘My dad was a bandleader and by the time I could play a bit of rock’n’roll he would take me out with him if he was playing to a younger audience. I saw how he worked as a bandleader and you can’t learn something like that in school. He taught me how to plan a set, how to interact with other musicians and how to get the best from them. My dad did it effortlessly though and I thought it was effortless until I started getting into fights with Artie. As soon as we met, we were the kind of best friends who would fight.’

The first song they wrote was ‘The Girl for Me’ which Paul wanted Artie to sing. He formed a doo-wop group around him and they were influenced by a hit band from nearby Jamaica, Queens, the Cleftones. Their demo got nowhere but the song was granted copyright by the Library of Congress.

Paul’s father, who was playing with the Lee Simms Orchestra at the Roseland Ballroom, would write down Paul’s chords. His father would tell him that his tune was in 4/4 and he’d suddenly gone to 9/8. ‘You can’t do that,’ Lou would say. ‘I just did,’ said Paul, thereby discovering one of his songwriting traits.

A commercialised form of folk music was popular in the 1950s. The Weavers, who included Pete Seeger, had successes with ‘Goodnight Irene’, ‘Michael Row the Boat Ashore’ and ‘Wimoweh’. The Everly Brothers took the Appalachian folk songs they had heard from their father, Ike, to make a wonderful acoustic album, Songs Our Daddy Taught Us, miles from rock’n’roll but an influential album for many musicians. Paul Simon called this 1958 record his favourite LP.

The Clovers had recorded a cheerful R&B novelty written by Titus Turner, ‘Hey Doll Baby’, in 1955. It was released as the B-side to their doo-wop favourite ‘Devil or Angel’. In August 1957, the Everly Brothers gave ‘Hey Doll Baby’ a neat choppy rhythm which they duplicated the following day for their million-selling ‘Wake Up Little Susie’. The lyrics weren’t easy to grasp: for years I thought the Evs were rhyming ‘lovesick’ and ‘mystics’ but it is ‘for love’s sake’ and ‘mistakes’, so Paul and Art could be forgiven for getting the words wrong. As they attempted to put the song into their repertoire, a new song emerged.

They now had ‘Hey Schoolgirl’ with a hook of nonsense syllables (‘Wu-bop-a-lu-chi-bop’) that owes something to Little Richard’s ‘Tutti Frutti’. They considered it sufficiently different from ‘Hey Doll Baby’ to be a song in its own right and thought it had commercial potential. If they made a demo and sent it to the Everly Brothers, maybe, just maybe, they would record it.

There were many small recording studios in New York and they cut ‘Hey Schoolgirl’ for a few dollars at the Sanders Recording Studio on Seventh Avenue, not far from Columbia’s studios. Did they dream that they might go there one day? Although their thoughts about Columbia would be mixed: ‘Just a come on from the whores on Seventh Avenue’, wrote Simon in ‘The Boxer’.

By chance, Paul and Art met Sid Prosen of Big Records at the Sanders studio, and he liked what they were doing, or at least said he did. In time-honoured fashion, he was going to make them stars. He saw their parents, secured a contract and released ‘Hey Schoolgirl’ on his small but Big label. The B-side, ‘Dancin’ Wild’, sounded like a continuation of ‘Hey Schoolgirl’ and should have been held back for the follow-up. They promoted it in red jackets and white bucks. With a little payola, it was played by Alan Freed, sold well locally and was released nationally through the King label.

Somehow, and again it could be payola, they found themselves on the Thanksgiving edition of Dick Clark’s American Bandstand, the teenage TV show of the day. This live programme for the ABC network, broadcast on 22 November 1957, starred Jerry Lee Lewis with his classic rave-up, ‘Great Balls of Fire’. Paul said, ‘I watched American Bandstand and here I was playing the show. It made me a neighbourhood hero.’

How Artie must have loved watching ‘Hey Schoolgirl’ climb his beloved Billboard chart, reaching a respectable No. 49. It sold 100,000 copies in the face of stiff opposition, not least from the Everlys’ new single, who in years to come would have welcomed a hit that size.

Tom and Jerry played few concerts outside their own area, although they were booked for an otherwise black show at the Hertford State Theatre. The show starred LaVern Baker (‘Jim Dandy’) and Thurston Harris (‘Little Bitty Pretty One’) – ‘and Artie and I came out running in white bucks’. Still, they had enough stagecraft to survive.

Unlike many record company owners, Sid Prosen wasn’t a rogue and they each made $2,000 from ‘Hey Schoolgirl’. Paul bought an electric guitar and a red Impala convertible. He crashed it a few times and its carburettor burned out near Art’s house: ‘I ended up watching my share of the record money getting burned up.’ Not to worry, as he regained the cost many times over as his exploits inspired his song, ‘Baby Driver’.

Sid Prosen promised bigger things next time, but as Simon said, ‘The next one was a flop and the next one a flop and the company went broke and we went back to school.’

As simple as that.

Only it wasn’t. Paul Simon had the bug.

Paul Simon may make glib remarks to throw researchers off the track. He may not want his efforts from the late 50s and early 60s to be remembered, but he is mistaken. You can’t change history and anyway, many of his earlier 45s are both telling and enjoyable.

Some readers may think that I should cut to the chase and get on to Simon & Garfunkel’s albums, but it would be omitting their development. The tracks show Paul Simon singing and playing, working in studios and learning his craft, including how to produce himself and other artists. He was discovering how to avoid mistakes and even before he had a hit single of any consequence, he had formed his own company, Landis Publishing. How far-sighted and confident is that? He was the first major rock musician to own his own catalogue and John Lennon praised him for his insight. There was a precedent as Irving Berlin controlled his songs through Irving Berlin Music.

Simon and Garfunkel have nursed a soft spot for ‘Hey Schoolgirl’. In 1967 they opened for the Mothers of Invention as Tom and Jerry and when they were called back for an encore, they sang ‘The Sound of Silence’, so hopefully everybody got the joke. In 2004 they went on tour with the Everly Brothers and brazenly sang ‘Hey Schoolgirl’ before introducing them.

‘Hey Schoolgirl’ had a catalogue number of Big 613. Big 614 was an echo-drenched ballad à la Paul Anka, ‘Teenage Fool’ coupled with the Elvis-lite rockabilly of ‘True or False’ and attributed to True Taylor aka Paul Simon. ‘True or False’ was written by his father, Lou Simon. His father was always supportive and would transport Tom and Jerry before they could drive.

But Artie was not supportive of True Taylor. Paul hadn’t told him what he was doing. Even now, Art cites this as typical of Paul’s behaviour, their first big argument and one that has been repeated several times. In 1980, Paul Simon told Playboy, ‘Artie looked upon my solo record as a betrayal. That solo record has coloured our relationship. I said, “Artie, I was 15 years old. How can you carry that betrayal for 25 years? Even if I was wrong, I was just a 15-year-old kid who wanted to be Elvis Presley for one moment instead of being in the Everly Brothers with you. Even if you were hurt, let’s drop it.” But he won’t. He said, “You’re still the same guy.”’

Paul Simon was sixteen, not fifteen, and he was feeling the pangs of not being able to follow up a hit record. He told the New York World-Telegramin 1957, ‘Once you’re down, it can be terrible.’

The True Taylor single didn’t make the charts and the follow-up to ‘Hey Schoolgirl’ was ‘Our Song’/‘Two Teenagers’ (Big 616). ‘Our Song’ is a break-up song in which the jukebox makes the singer cry; again heavily Everly with a bridge taken from ‘Wake Up Little Susie’. Long before it was fashionable, Paul and Art were into recycling. The B-side, ‘Two Teenagers’, written by Rose Marie McCoy, who wrote for Elvis, was a cheerful novelty with irritating female back-up singers. They sneaked in the riff from ‘Hey Schoolgirl’.

The new single didn’t sell but Tom and Jerry tried again with the plaintive ‘That’s My Story’, which has a brassy arrangement similar to Billy Vaughn, and ‘Don’t Say Goodbye’ (Big 618). For Big 621, they did a cover of ‘Baby Talk’ backed by a reissue of ‘Two Teenagers’. Jan and Dean made the US Top 10 with ‘Baby Talk’ but this is okay. Curiously, Tom and Jerry’s version was released in the UK by Gala as one side of a single which sold for four shillings (twenty pence).

That is not quite the end of Tom and Jerry as there is a further single, the quirky novelty ‘Lookin’ at You’ and country ballad ‘I’m Lonesome’, an Ember single, issued by Pye International in the UK but not until 1963. Record Mirror said that ‘showed promise’, not knowing that they were assessing a single made four years earlier.

Another Tom and Jerry single, ‘Surrender, Please Surrender’ and ‘Fightin’ Mad’, features nondescript songs written by Sid Prosen, but I think Prosen invited other wannabes to perform them. I hope it is not Simon singing about the quest ‘to find a girlie just like you’.

There are two Tom and Jerry singles on Mercury (‘South’/‘Golden Wildwood Flower’ and ‘I’ll Drown In My Tears’/‘The French Twist’), but they were the Nashville instrumentalists, Tom Tomlinson and Jerry Kennedy, not to mention some novelty singles from the cartoon cat and mouse themselves.

In 1967 the UK label Allegro released an album of their singles as Tom and Jerry, attributing them to Simon & Garfunkel and slapping a contemporary photograph on the cover. The sleeve note said, ‘We are very fortunate to have captured on this recording the exciting sounds of these two brilliant young men. Contained in this album is a generous sampling of two stars of tomorrow who are the talk of the record world today.’

Paul was indignant, telling Record Mirror, ‘What annoyed me most about the record is that it implied that this was new Simon & Garfunkel material. They used a recent photograph on the cover. If they’d released it saying, “This is Simon & Garfunkel at 15”, it might have been interesting and I would have said, “Okay, that’s me at 15 and I’m not ashamed of it.” I made a record at 15 and everybody wanted to at that age. I just wanted to be Frankie Lymon.’ Later he became more critical, calling the record ‘fodder for mental eunuchs… I’m ashamed of it.’

Simon and Garfunkel took legal action and the album was withdrawn on both sides of the Atlantic. Strangely, Woolworths immediately started selling copies for just five shillings (twenty-five pence) and I recall seeing hundreds in their Liverpool branch. I bought one and I’d have been rich if I’d bought the lot.

The Allegro album has ten tracks, two of them previously unheard instrumentals, the mournful ‘Tijuana Blues’ and the jazzy ‘Simon Says’. ‘Simon Says’ has the songwriting credit of Louis Simon and Sid Prosen.

Paul and Art’s singles as Tom and Jerry are competent and they could have been lucky and had a chart career. Paul summarised it thus: ‘We didn’t plan to go on with music as a career but it wasn’t just for fun. We were deadly serious about everything we did. We wanted to sing and we wanted to play. It wasn’t like we said, “Let’s make one record and that would be it”, and then we’d travel off to university. We loved making records.’

This isn’t wholly true. Paul felt that way but Art’s heart wasn’t in it. He enjoyed making records but he was giving private lessons in mathematics and was planning to study architecture at Columbia, though he switched to maths (sorry, math). Simon would go to Queens College to study English literature but he was less committed and wanted to make music. ‘I was going to be a political science major at one time,’ Paul told journalist Lon Goddard, ‘but the professor used to fart a lot – and so I said, “That’s disgusting – I won’t be that.”’

Paul loved the atmosphere surrounding the music publishing companies in the Brill Building and as well as solo singles, he made demos for songwriters. He would sing a lead vocal for fifteen dollars and he was so proficient that he could make the whole demo, playing instruments and overdubbing where necessary. He explained, ‘After “Hey, Schoolgirl”, I got to know studios and record labels. I’d leave my name with them and they’d call me to cut demos. I learned how to overdub and for $25, I could sound like a full group. I’d play bass, drums, piano in the key of C, and sing oo-ah-ooh in four different voices.’

At Queens College, Paul met Carole Klein who became Carole King. They both wrote songs and made demos calling themselves the Cosines with Paul playing guitar and bass and Carole piano and drums. They’d add their voices and the records would be sent to artists who were currently hot like Frankie Avalon and the Fleetwoods.

Carole wanted to be a professional songwriter, working with her boyfriend, soon her husband, Gerry Goffin. Paul shared the advice his father had given him. ‘She wanted to quit Queens and be a songwriter. I said “Don’t, you’ll ruin your career”. And she quit and had ten hits that year.’ ‘Will You Love Me Tomorrow’ ensured her an income for life. Goffin and King were signed by Aldon Music, run by Don Kirshner, but he turned Paul Simon down.

Paul recorded solo as Jerry Landis, the first single for MGM in 1959 featuring two of his compositions. The mawkish ‘Loneliness’ is a typical teenage-wallowing-in-misery song from the late 50s. The B-side, ‘Annabelle’, is the worst song he ever wrote, his vocal competing with a squawking sax.

Also in 1959, Jerry Landis recorded two Marv Kaplin songs for Chance, ‘Just to Be with You’ and ‘Ask Me Why’. He and Carole King worked on the arrangement of ‘Just to Be with You’ together. The song was picked up by the Brooklyn doo-wop group, the Passions, and their single made No. 69.

Paul Simon knew the management and the acts at Laurie Records, but he was never able to place his songs with their top artist, Dion. Mostly Paul’s songs remained demos but sometimes they were released in their own right. ‘Cry, Little Boy, Cry’ was a carbon copy of ‘Runaround Sue’, while ‘Noise’ emulated the party feel of ‘The Majestic’. Simon sounded like Dion singing ‘I Wonder Why’ on ‘Cards of Love’, a clever song about how the Jack steps in between the King and Queen. Most significant of all was ‘Wildflower’ from 1962 – the lyric ‘She was a wanderer through and through’ was aimed at Dion, and its Bo Diddley/Buddy Holly beat would have suited him. Oddly, the song suddenly changed to an African chant. Unlikely of course, but was this the starting block for Graceland?

Paul was mostly working at Associated Studios, again on Seventh Avenue and close to the Brill Building. He played lead guitar on Johnny Restivo’s rock’n’roll chart single, ‘The Shape I’m In’ (US 80) and its B-side ‘Ya Ya’. Restivo was a poster boy, a veritable Adonis, but the single had rock’n’roll credibility and is heard on oldies shows.

Another single was a wimpish ballad with a light beat, ‘Shy’, inspired by Frankie Avalon’s ‘Why’. The playful vocal suggests that Simon wasn’t taking it seriously. The B-side was the saccharine ‘Just A Boy’, which would have suited Avalon, but the bridge steals from ‘Secret Love’.

Paul worked, somewhat unsuccessfully, in music publishing, although one song he promoted, ‘Broken Hearted Melody’ by Sarah Vaughan became a huge hit. It was written by Hal David and Sherman Edwards, who passed him a teen song they had written ‘I’d Like to Be (The Lipstick on Your Lips)’. This was a sugary teen ballad, typical of Frankie Avalon and Fabian. The B-side was a reprise of ‘Just A Boy’, so somebody liked it.

Paul recorded about ten demos for the up-and-coming songwriter Burt Bacharach. Knowing Bacharach’s fastidiousness, this illustrates that Paul had his chops even at this young age.

The third Warwick single was the best track from the early years, ‘Play Me a Sad Song’, with the songwriting credit (Landis-Simon) indicating that he wrote it with his brother Eddie. The theme is familiar: Simon wants the radio DJ to play him a sad song as he is feeling lonely and the song borrows from Tab Hunter’s ‘Young Love’, Sam Cooke’s ‘You Send Me’ and Ben E King’s ‘Don’t Play That Song’. The biographer Patrick Humphries has likened this track to ‘I Am a Rock’. Paul is singing well and this could have been a hit. Indeed if it had had the distribution, what DJ could have resisted the title? The B-side, ‘It Means a Lot to Them’, is an unlikely song about the importance of getting the consent of his girlfriend’s parents. It was not Paul’s song and was as awkward as its title.

In 1963 Jerry Landis arranged and produced an excellent single for the soul singer Dotty Daniels. He didn’t write ‘I Wrote You a Letter’, which is a strong soul ballad written by Dickie Goodman, but the other side is an impassioned deep soul version of ‘Play Me a Sad Song’ with an orchestral arrangement.

Another Jerry Landis single was released on Canadian-American Records; Simon wrote both sides. ‘I Wish I Weren’t in Love’ sounds like a demo for Dion and the Belmonts, and is the first track that is recognisably Paul Simon. The B-side, ‘I’m Lonely’, is a plea for a girlfriend; a ‘Lord above, won’t you hear my plea’ song.

Simon formed studio band Tico & the Triumphs and, in line with their name, he sang lead and wrote ‘Motorcycle’ for Madison in 1961. He called himself after Tico because it was one of George Goldner’s labels and the Triumphs because he wanted a motorbike. It was a nonsense song like ‘Barbara Ann’ and ‘Rama Lama Ding Dong’. Simon is recognisable and the song has a good sax break but the record is disjointed. It crept into the Billboard Hot 100 at No. 99. The B-side is another song, teen ballad ‘I Don’t Believe Them’, in which he mimics Dion. How he must have enjoyed himself in 2009 singing back-up for Dion who was being inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

The second Tico single, this time on Amy Records, was ‘Wildflower’, another Simon song, this time crossing ‘His Latest Flame’ with world music. He was trying something different that didn’t come off. ‘Express Train’ is a train song, based on ‘The Wanderer’ and although a rough-voiced vocal didn’t suit Simon, the session sounds fun.

With the advent of the twist, the mashed potato, the watusi and the fly, Simon created his own dance song, ‘Get Up & Do the Wobble’. He rhymed ‘potatoes’ with ‘later’, something that would not have passed his Quality Control in later years.

In 1962 Simon revived Jerry Landis for a single on Amy, ‘The Lone Teen Ranger’, inspired by the Coasters’ ‘Along Came Jones’ and the Olympics’ ‘Western Movies’. There are rudimentary sound effects and a very playful vocal from Paul Simon. It’s his song but it does incorporate Rossini’s William Tell Overture. His girl will fall for him if he wears a mask – kinky stuff. The B-side, ‘Lisa’, features Paul singing lead on a teen ballad. It means little more than a few radio plays but ‘The Lone Teen Ranger’ was on the Hot 100 for three weeks, peaking at No. 97, thereby being Paul Simon’s first chart record as a solo artist.

The final Tico & the Triumphs single in January 1963 combined a fast doo-wop song, which Simon didn’t write, ‘Cards of Love’, and a revival of his own ‘Noise’, which is party time in the Curtis Lee vein.

Just as Paul Simon wanted to write for Dion, the Mystics were about to record Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman’s ‘A Teenager In Love’ for Laurie when the label’s owner, Bob Schwartz, thought it was too good for them and gave it to Dion. Simon helped with arrangements for the Mystics. He sang second tenor on their doo-wop interpretation of the Welsh lullaby ‘All Through the Night’. Jim Gribble, their manager, offered him a royalty or $100. Wisely, he took the money as the record only had airplay on the east coast, but who knows, it might have given him the idea for modernising old folk tunes such as ‘Scarborough Fair’. He also sang on the B-side, ‘(I Begin) To Think Again of You’.

By comparison, Art Garfunkel was studying hard and had done little recording, but he also recorded for Warwick. As Artie Garr, he wrote the teen ballad ‘Beat Love’ which opens with his solo voice. He says he is proud to be part of ‘the age of the beatniks’, so this is an unusual record and a good one. He wrote the B-side ‘Dream Alone’, a decent teen lullaby.

In 1962 and inspired by the Brothers Four folk hit, ‘Greenfields’, Art wrote the romantic ‘Private World’, which he recorded for Octavia. Garfunkel is double-tracked to resemble a group and it is good work. The B-side, ‘Forgive Me’, written by Jeff Raphael, is about a man awaiting death.

Just two singles from Garfunkel then, but it is odd that no one picked up on his exceptional voice. He recalled, ‘I wrote some banal rock’n’roll songs in the mid-50s, and then I wrote things of a more folky, sensitive nature, but I rated myself as weak. I never felt comfortable with it.’

Several of Paul Simon’s demos from around this time have come to light. Sung with Garfunkel, ‘Bingo’ is a children’s rhyme about a farmer’s dog – a variant of ‘Ol’ MacDonald’ really. If Simon & Garfunkel had ever made a kids’ album, this would have been ideal.

‘Dreams Can Come True’ is a Simon & Garfunkel demo, purloining a little of ‘All I Have to Do Is Dream’ but mostly sounding like Donovan in the mid-60s. They are edging towards the Simon & Garfunkel sound here.

The romantic ballad about a girl called Flame (‘Being with Flame set me on fire’) has a nice combination of Paul’s voice and flute. The other songs include the jazzy ‘Lighthouse Point’ (slow and fast versions, but the song’s construction is similar to ‘The Green Door’ and ‘At the Hop’), a song about a lethargic schoolboy, ‘Up and Down the Stairs’, a touch of social commentary in the folky ‘A Charmed Life’, while ‘Sleepy Sleepy Baby’ is a reflective song, which turns into a calypso – two takes have surfaced.

There is the fun of ‘Back Seat Driver’ with Paul sounding like the Big Bopper, and the self-pitying ‘Educated Fool’ where Paul has graduated in misery. There is a song about wanting to be a bachelor, ‘That Forever Kind of Love’, a Ricky Nelson-styled song about a marital breakdown. It’s a long way from ‘The Dangling Conversation’ but it is the same writer.

Paul made a demo of his fast-moving doo-wop song ‘Tick Tock’, which he produced as a single for Ritchie Cordell on the Rori label. The song was picked by the Boppers from Finland in 1979, a record well in line with revivalist groups of the day like Darts and Showaddywaddy.

Taken together, the demos and singles find Paul Simon copying every commercial sound around. If they were parodies (but they weren’t), some would be on a par with the Rutles. How could Neil Innes have improved on ‘Wow Cha Cha Cha’, a 1961 demo by Paul Simon?

In the late 70s, when Paul Simon fell out with Columbia, he owed them one more album. When he suggested an album of covers, he was told that this was unacceptable and Columbia insisted on original work. After weeks of negotiation, Simon bought himself out of the contract – a pity as an album of covers would have been good. His performances and arrangements would have been immaculate.

There could have been another solution. When Van Morrison wanted to leave Bang Records, he gave Bert Berns some new songs all right, but they were composed on the spot and amounted to nothing of value. He was risking his own career as they could have been promoted as the new album and purchasers would think they had been swindled.

But what if Paul Simon had decided to revisit his early songs and pick the best of them for an album called Play Me a Sad Song? There are good melodies and good lyrics and he could have made an homage to the early 60s with classy remakes and then taken his new songs to Warner Brothers.

CHAPTER 2

Hello Darkness, My Old Friend

Art Garfunkel completed his master’s degree in mathematics from Columbia College and moved onto postgrad studies. Although Paul Simon studied English literature at Queens College, his mind was on music. He loved making records.

The enthusiasm had gone from rock’n’roll – for the most part, the rebellious stars had been replaced by inconsequential pop singers. Don McLean called 3 February 1959 the day the music died, but it was one of a chain of events. It was the day that Buddy Holly died and around the same time, Elvis had been drafted into the army, Little Richard was studying for the church, Gene Vincent had been blacklisted by the union, Carl Perkins had been injured in a car crash, and Chuck Berry was doing time. In their place was something blander, although there were considerable talents around such as Roy Orbison, Del Shannon and Bobby Darin. There were no rebellious figures and the industry hierarchy had control.

Paul Simon disliked Bobby Vee’s records, which paradoxically were often written by Carole King. He felt that something new was needed, telling Lon Goddard at Record Mirror in 1971, ‘Age made me change my style of music: age and the folk-boom. Rock’n’roll got very bad in the early 60s, very mushy. I used to go down to Washington Square on Sundays and listen to people playing folk songs and when I heard that picking – Merle Travis picking the guitar, Earl Scruggs picking on the banjo – I liked that a whole lot better than Bobby Vee.’

The performers in Washington Square largely came from Greenwich Village. A bohemian enclave of folk music had emerged from the coffee houses, young performers inspired by social commentators like Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger. Dave Van Ronk’s memoir, The Mayor of MacDougal Street, paints a vivid picture of the scene and, in 2013, it was the basis for a fictional film, Inside Llewyn Davis, which soaked up the atmosphere of those times, admittedly with little of its humour.

Ralph McTell contrasts the London scene he knew with that of Greenwich Village. ‘It wasn’t like Greenwich Village for us unfortunately as they had lots of places where you could stay all night and could talk and chew the fat. I go green with envy reading The Mayor of MacDougal Street, which is a fantastic book. We didn’t have those long, languid discussions. I did get to play there which was fantastic. I did the Main Point and the Bitter End with Patti LaBelle and the Bluebelles. The audiences were kind to me but I could have had an easier start.’

Although Paul Simon had loved the Everly Brothers’ album, Songs Our Daddy Taught Us, he had not wanted to follow through on its material. He liked the way the Everlys performed those old folk songs but ‘those mountain songs didn’t say anything to kids in the 22-storey apartments.’

What captured his attention was the new breed of folk songwriters, who felt passionately about the world around them and said so in their songs. Tom Paxton was one. Phil Ochs was another. The diamond in the rough was Bob Dylan, who performed literate diatribes against modern society in an intense, nasal drone that was, nevertheless, highly effective. It was very different from the cotton-wool world portrayed by Bobby Vee; although Dylan had once, briefly, been Vee’s pianist.

These songs provided the stimulus that Paul Simon needed and the first song for the new-look Simon was ‘He Was My Brother’. Simon and others have said that this song is about the death of a freedom worker he knew at the hands of the Ku Klux Klan, but there is difficulty here. We can date the song to June 1963 and it was recorded in March 1964. However, his friend Andrew Goodman was not killed until 21 June 1964 when he died with his fellow workers, James Chaney and Mickey Schwerner. This horrendous act changed public opinion and it has been sung about by Pete Seeger, Phil Ochs, Tom Paxton and Richard Fariña, all with different songs. In 1988, their deaths were the subject of the film, Mississippi Burning. The likelihood is that Simon wrote his song – and another one about the KKK, ‘A Church Is Burning’, in 1963 and over time he has come to believe that he wrote it for Goodman’s death as it fit the circumstances.

Art Garfunkel was very impressed. ‘I first heard the song in June 1963,’ he recalled on a sleeve note, ‘a week after Paul wrote it. Cast in the Bob Dylan mould of that time there was no subtlety in the song, no sophistication in the lyric; rather the innocent voice of uncomfortable youth. The ending is joyously optimistic. I was happy the way the song made me feel. It was clearly the product of a considerable talent.’

Although somewhat neglected, not least by Simon himself, his next song for the folk world, ‘Sparrow’, was better. It is an allegory along the lines of ‘Who Killed Cock Robin?’ and when it first appeared Garfunkel kindly provided us with a key to its symbolism. The song stands without it and the composition displays a lighter touch than most of his earlier work.

The third song was ‘Bleecker Street’, a favourite location in Greenwich Village for folk songwriters, among them Tom Paxton (‘Cindy’s Crying’) and Joni Mitchell (‘Tin Angel’).

Paul Simon took tentative steps by performing his new material in Greenwich Village, but he felt uneasy: ‘There was nothing exotic about me, coming from Queens. They were taken with Bob Dylan because he came from the Midwest, the kid who rode the rails. I was not accepted.’ We now know that Dylan exaggerated his adventures but good luck to him.

Nevertheless, Paul recorded two new songs, ‘He Was My Brother’ and ‘Carlos Dominguez’ for the small Tribute label where it was issued under the name of Paul Kane. In 1964 it came out on Oriole Records in the UK, this time under the name of Jerry Landis.

‘Carlos Dominguez’ was never revived by Simon and/or Garfunkel but it was covered by the Irish singer, Val Doonican, who told me, ‘Alan Paramor, who used to look after my publishing, asked me to listen to this young American lad. I listened to “Carlos Dominguez” and while I was there, this American chap turned up. He introduced himself as Paul Kane, but he later changed it to Paul Simon. If you mentioned it to him today, he probably wouldn’t remember me or the song at all, but it was a very nice little thing.’ For a time too, the comedian Tom O’Connor included it in performances.

In September 1963 Simon and Garfunkel began performing the new songs in Greenwich Village, this time billed as Kane and Garr, but they didn’t fool anyone. Dave Van Ronk has much to say about Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Phil Ochs and Tom Paxton in his memoir but very little about Simon and Garfunkel. Van Ronk saw them perform but everyone knew that they had had a hit with ‘Hey Schoolgirl’ and ‘the mouldy fig wing of the folk world despised them as pop singers. I remember hearing them down at the Gaslight, and nobody would listen. I thought they were damn good but the people who wanted to hear Mississippi John Hurt and Dock Boggs wanted no part of Simon and Garfunkel.’

They had started performing ‘The Sound of Silence’. Simon said, ‘I used to go into the bathroom because the tiles acted as an echo chamber. I’d often play in the dark, “Hello darkness, my old friend”. The first line came from that and then it drifted off into other things.’

Indeed, Simon is the king of great first lines. He said, ‘I’ve always believed that you need a truthful first line to kick you off into a song. You have to say something emotionally true before you can let your imagination wander.’

I would have thought that anyone would have recognised ‘Hello darkness, my old friend’ as a brilliant opening line, but not so. Dave Van Ronk described how it became a running joke. ‘It was only necessary for someone to start singing “Hello darkness, my old friend…” and everybody would crack up. It was a complete failure.’

‘I was trying to prove something,’ Simon admitted. ‘I’d think, “Gee, I’m good. Why doesn’t anybody see that?” So naturally I was resentful that nobody did see that.’

‘The Sound of Silence’ was influenced by Bob Dylan but Paul told MOJO in 2000 that he never wanted to be compared to him. He said, ‘I tried very hard not to be influenced by him, but I know I would never have written “The Sound of Silence” were in it not for Bob Dylan. Never. He was the first guy to come along in a serious way and not write teen-language songs. I saw him as a major guy whose work I didn’t want to imitate because I didn’t see any way out of being in his shadow if I did.’

‘The Sound of Silence’ touches on many of Simon’s themes – alienation, conformity and the role of the media. The lyrics are sober and scholarly and they sound poetic (‘Silence like a cancer grows’). Every line is almost a song in its own right.

Simon was working as a part-time plugger for the music publisher, E. B. Marks, and if the opportunity arose, he would slide in one of his own. He knew Tom Wilson, a jazz producer for Columbia Records (CBS in the UK), who had been assigned to Bob Dylan.

A black guy, Tom Wilson was born in 1931, raised in Waco, Texas, graduated from Harvard in 1954 and founded a jazz label, Transition, in 1955. He had worked for the jazz label Savoy, being assigned to Herbie Mann, and then moved to Columbia, where he recorded folk artists, Bob Dylan and Pete Seeger.

Paul Simon played Tom Wilson ‘He Was My Brother’, and Wilson wanted to cut it with a promising folk group, the Pilgrims. Ever the opportunist, Simon said that he often sang it with his friend and could they have an audition. Wilson was intrigued by Garfunkel’s hair as he had never seen a white man with an Afro before (so that’s what you call it). Wilson told the president of Columbia Records, Goddard Lieberson (known, for good reason, as ‘God’), about them. God agreed that a two man, one guitar album could be made quickly at little cost, but he questioned the name, as Simon & Garfunkel sounded like a department store.

Simon never liked being told what to do and he argued that they had to have real names for folk music. He said, ‘Our name is honest. I always thought it was a big shock to people when Bob Dylan’s name turned out to be Bobby Zimmerman. It was so important that he should be true.’ The implication was that if you had an honest name, your songs were ipso facto honest.

The album, Wednesday Morning 3am, was made in four sessions in March 1964. It’s a simple production, showcasing the songs and the voices, and an important component was the engineer, Roy Halee, who became a permanent member of their team.

Roy Halee’s father had been the singing voice for Mighty Mouse and his mother had worked with Al Jolson. Roy, who was born in Long Island in 1934, played trumpet but did not consider himself good enough for professional work. He became a technician for CBS television and then an engineer for their recording division.

The byline (or buyline) of their first LP was ‘Exciting new songs in the folk tradition’. The sound was good but unexciting. The strumming which begins the opening cut could easily have been the Seekers. By and large, Simon and Garfunkel are singing too sweetly and some of the outside songs were unnecessary, especially a bland run-through of Bob Dylan’s heated ‘The Times They Are A-Changin’’. The album falls between the commercial folk of the Kingston Trio and the albums later made for lonely bedsits. Simon and Garfunkel were often pictured with college scarves as if to stress their student background.

No matter what, Simon and Garfunkel together would never make a good picture, unlike the Beatles, who always looked right. Paul was small (five foot two), Art was tall (over six foot), and you would always be drawn to Art’s hair. Some bands such as Pink Floyd, the Moody Blues and Genesis did not put photos on the covers of their albums, which is sometimes a wise decision.

Simon and Garfunkel always looked wrong. What induced Garfunkel in 1975 to attend the Grammy awards, of all places, sporting a T-shirt with a painted bowtie? Simon with his long hair and moustache has his own problems – and then this pair are photographed alongside the coolest guys in rock, John Lennon and David Bowie.

The album includes two gospel songs, ‘You Can Tell the World’ and ‘Go Tell It On the Mountain’, but the performances are bland. The Weavers or the Clancy Brothers would have belted these out. Indeed, Peter, Paul and Mary were climbing the US charts with a spirited ‘Go Tell It on the Mountain’.

‘Benedictus’ is an experiment which comes off well. It is based on a sixteenth-century setting which Art found in a library. There is a delicate cello in the background and the duo displays control and harmonic sophistication.

Simon and Garfunkel knew Ed McCurdy as the host from the Bitter End and he was a folk singer and writer with a long and varied career. In 1957 he recorded some bawdy folk songs later packaged as A Box of Dalliance. His plea for world peace, ‘Last Night I Had the Strangest Dream’, written in 1950, is among the greatest songs ever written and was performed when the Berlin Wall was demolished. In 1964 it was recorded by both the Kingston Trio and Simon & Garfunkel and although the Trio have the edge and a fuller sound, Paul and Artie’s version is a good one.

The Scottish folk song, ‘Peggy-O’, is about an army captain whose advances are shunned so he plans to destroy the village of Fennario in retaliation. The song, originally known as ‘The Bonnie Lass of Fyvie’, exists in many versions and was recorded around the same time by Bob Dylan and Joan Baez. It became a mainstay of the Grateful Dead’s concerts. Again, it is a saccharine performance from Simon & Garfunkel, which goes against the grain of the lyrics.

There is a song, ‘The Sun Is Burning’, from the Scottish folk singer, Ian Campbell, who will come into our story. It’s a round robin with each verse reflecting on the position of the sun, but it could be about a nuclear holocaust. The song was regularly performed by Luke Kelly of the Dubliners.

Simon’s five songs are ‘Bleecker Street’, ‘Sparrow’, ‘The Sound of Silence’, ‘He Was My Brother’ and ‘Wednesday Morning 3am’. Although the last song gives the album its name, it is not the strongest. It begins as a gentle travelling song but the singer is a criminal on the run for robbing a liquor store.

Rather like ‘The Sound of Silence’, ‘Bleecker Street’ is a song of alienation. It is not saying how wonderful Greenwich Village is and how great these little clubs are. No, the fog is rolling round the street like a shroud and the performers are juggling art with commerce. It’s a very good song indeed but it is unusual to find Simon retaining his false rhyme of ‘sustaining’ and ‘Canaan’. It is a pity that they didn’t return to this song as it could have worked with a full arrangement.