6,20 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: McNidder and Grace

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

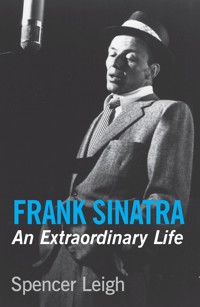

Frank Sinatra: An Extraordinary Lifeis a definitive account of Frank Sinatra's life and career. With unique material and exclusive interviews with fellow musicians, promoters and friends, the acclaimed author Spencer Leigh has written a compelling biography of one of the world's biggest stars. With remarkable stories about Sinatra on every page, and an exceptional cast of characters, readers will wonder how Sinatra ever found time to make records. If this book were a work of fiction, most people would think it far-fetched

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 1180

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Thanks

When it comes to acknowledging help, I must first credit the late Len Scarratt from the Wirral who has no idea that he has helped me in any way. He was a well-organised Sinatra collector whose possessions were removed in a house clearance. They were given to the Literally bookshop in New Brighton and its owner, Cathy Roberts, passed them to me. Another long-time collector, Babs Freckleton, passed over some VHS tapes which otherwise would have gone to a charity shop. Thanks to Billy Butler, Andrew Doble, Peter Doble, Peter Grant, Denny Seyton and in particular to David Roberts of poppublishing who did much to drum up interest in this project.

A special thank you to my wife, Anne, who has had to put up with my obsession with Frank Sinatra: she read the Kitty Kelley biography when it was published in 1986, decided that he was despicable and has had no further interest in him: I hope this is a more balanced view than Kelley’s although Frank Sinatra certainly had his dark side.

I acknowledge the use of the British Library, the library attaching to the BFI Southbank and the BBC Written Archives in Caversham. These are all brilliant places with helpful staff. My thanks to Marion Leonard and the Institute of Popular Music at the University of Liverpool: they possess a wonderful vinyl archive with several shelves of Sinatra albums but, strangely, hardly anything by Dino.

I am very glad that Andy Peden Smith of McNidder & Grace was as intrigued by this subject as I was and I hope I haven’t let him down. I am grateful to the readers for this book – David Charters, Fred Dellar and Patrick Humphries – their comments were invaluable. David was asked by his son why he was spending so long on the book. ‘Is it longer than War and Peace?’ he asked. ‘No, it’s not quite that long,’ said David, ‘but the themes are similar.’ Thanks also to publicist Linda MacFadyen and the book’s designer Bryan Kirkpatrick.

Contents

Foreword by Sir Tim Rice

Introduction: Set ’em up, Joe

Chapter 1: New York, New York

I. Italian-Americans

II. Day In–Day Out, 1915–1934

Chapter 2: You must be one of the newer fellas

I. Anything Bing Can Do…

II. Day In–Day Out, 1935–1939

Chapter 3: Start spreadin’ the news

I. Big Band Swing

II. Day In–Day Out, 1939

Chapter 4: Getting sentimental

I. Brotherly Love

II. Day In–Day Out, 1940–1942

Chapter 5: The house I live in

I. The Great American Songbook

II. Day In–Day Out, 1943–1945

Chapter 6: Kissing bandits

I. Viva Lost Vegas

II. Day In–Day Out, 1946–1949

Chapter 7: I’m a fool to want you

I. Rat Packers

II. Day In–Day Out, 1950–1952

Chapter 8: From here to eternity

I. Making Arrangements

II. Day In–Day Out, 1953

Chapter 9: Call me irresponsible

I. I’ve Heard That Song Before

II. Day In–Day Out, 1954–1956

Chapter 10: Game changers

I. The Young Pretenders

II. Day In–Day Out, 1957–1959

Chapter 11: Election year

I. Ambassador for Pussy

II. Day In–Day Out, 1960

Chapter 12: War games

I. The Sound of Middle-Aged America

II. Day In–Day Out, 1961–1963

Chapter 13: Making it with the moderns

I. Beatleland

II. Day In–Day Out, 1964–1966

Chapter 14: The first goodbye

I. The Record Shows I Took the Blows

II. Day In–Day Out, 1967–13 June 1971

Chapter 15: Intermission

Day In–Day Out, 14 June 1971–1973

Chapter 16: Let me try again

Day In–Day Out, 1974–1979

Chapter 17: They can’t take that away from me

Day In–Day Out, 1980–1998

Chapter 18: The ghost of swingers past

Bibliography

Illustrations

Frank meets Queen Elizabeth II at the British premiere of Me and the Colonel, 1958.

Long before Beatlemania, note this crowd for Frank outside the London Palladium in 1950.

Frank at Sunshine Home for the Blind, Northwood, London in 1962 was asked, ‘What colour is the wind?’

Frank and daughter Nancy attend a film premiere in Hollywood, 1955.

‘You married the wrong guy, honey’. Frank and Princess Grace in London, 1970.

Frank as Danny Ocean gives Patrice Wymore the key to his room in Ocean’s 11, 1960.

A rare shot of Frank conducting, 1962.

Frank at the Royal Festival Hall, 1978.

Sweatshirt with Ol’ Blue Eyes is Back – and he was, 1973.

Handbill from 1953.

In 1953 Frank visited Ma Egerton’s, which is behind the Liverpool Empire. In 2015, the visit is still used to promote their pizzas.

Frank honoured by the US postal service, 2008.

Frank Sinatra song sheets.

UK journalist Stan Britt asked Dave Dexter to help him with a Sinatra biography. Dave doesn’t pull his punches, 1988.

The general format of Frank Sinatra: An Extraordinary Life is to split the chapters into two parts: the first describes the background to something significant in Frank Sinatra’s life, and the second continues Frank’s story on a day-to-day basis. If you just want Frank’s life story, the second sections on their own form a continuous story. In Chapter 1 the first section describes life in Italy and America before Frank was born and how so many Italians found themselves in the United States.

Foreword

by Sir Tim Rice

In March 1965, I forked out the largest sum I had ever invested in a vinyl gramophone recording when I purchased a triple LP – a compilation of Frank Sinatra’s greatest Capitol tracks entitled ‘Sinatra – The Great Years’. This mono package set me back £5 at a time when that was the exact sum I was earning every week as an articled clerk in a solicitors’ office in London. In the 50 years since I handed over my hard-earned cash to Christopher Foss Records of Paddington Street, W.1., I have never regretted my extravagant purchase. The album (the 13th – and I suppose the 14th and 15th – I had ever bought) still holds an esteemed place in my collection and is still a regular on my turntable.

But half a century later, I realise that the financial aspect of my transaction was not the most important one. This was the first time I had bought a record that was not a rock era disc; indeed nearly half the tracks on it were recorded before Elvis Presley broke through with ‘Heartbreak Hotel’ in 1956. From that year onward, although Sinatra and many of his refined colleagues, such as Dean Martin, Nat ‘King’ Cole and Tony Bennett, continued to hit the charts, there was a definite “them and us” divide within the music-buying public; adults liked Sinatra and co. and were square (or sophisticated), kids were with-it (or moronic) and went for Elvis, Cliff and in due course the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. No-one was supposed to cross the generational barrier. But of course many did, in both directions, and what is more, found themselves perfectly happy on both sides of the fence. Spencer Leigh was clearly one of these open-minded music lovers. Frank Sinatra was not.

I have known and admired Spencer’s work as a music historian for many years. When he describes music and musicians of a bygone age, we become aware of so much more than the songs and performers – the era itself returns to life and we are reminded that all art, notably popular art, is inspired by, and inseparable from, its time and place, and if we don’t understand that background, the story is far from complete.

Spencer is primarily known, through his radio shows and his two dozen or so books, as a chronicler of the British pop and rock scene from 1955 to 1980 or thereabouts, but he has ventured Stateside on more than one occasion (Paul Simon, Buddy Holly) and revealed his great knowledge of popular music before he was born in such publications as Brother, Can You Spare a Rhyme. In his mammoth and wonderful tome on Frank Sinatra, he has superbly given us Americana through the long life and career of his subject which began way before his did. Sinatra’s agents, lovers, dodgy associates, show biz friends and enemies, passions, hatreds, bravery and recklessness, finesse and crudity, worldly wisdom and naiveté, are all part of the complex whole and Leigh captures them all.

The sleeve note of ‘Sinatra – The Great Years’ asked “were better records by a singer ever made?” This is a pretty bold question, but on the other hand, someone must have made the greatest vocal recordings of all time and there are plenty who would support Sinatra’s claim to that honour. I would certainly place two or three of these great 1953–1960 Capitol sides in an all-time Top 40 male vocal performance chart, ‘One For My Baby’, ‘The Tender Trap’ and ‘All The Way’ being my favourites this week. Whether there has been a better telling of the Frank Sinatra story than Spencer Leigh’s version only someone who has read all the myriad other attempts can say – I can say for sure that after reading Frank Sinatra: An Extraordinary Life you may want to read more about him, but you won’t need to.

INTRODUCTION

Set ’em up, Joe

Many think that Frank Sinatra’s career is summed up in the title of his 1939 recording, ‘All Or Nothing At All’, but it’s not. Frank’s career is summed up in that first word, ‘All’: he wanted everything and ‘nothing at all’ had no appeal for him. He was a winner, the ultimate winner, and all losers were schmucks. Being a Democrat or a Republican didn’t matter much to him: Frank would switch allegiance according to whom was in the White House.

Sinatra’s story is incredible. He was a man with a remarkable constitution, drinking heavily and involved in numerous projects at any one time. He slept badly and yet he had the stamina to maintain the Cresta Run of his life. It’s a cliché but he said it: he did it his way – and his way was the only way that mattered.

His life was full of making friends and falling out, a love of family life but continual love affairs, enormous grudges and spontaneous fights, a fascination with gangsters, dicey financial decisions, the most sublime recording sessions, thousands of personal appearances, radio and TV shows and numerous starring roles in the movies.

Frank Sinatra loved hard, worked hard and played even harder. It is an extraordinary fact that Sinatra set aside $1,000,000 each year for his gambling losses. That’s right. Frank Sinatra was at ease with losing $1,000,000 a year on the tables in Las Vegas. Despite his reputation for the party life, he always wanted to keep working. He would choose a mediocre film or lacklustre songs rather than do nothing at all.

It is extraordinary that his most valuable asset, his singing voice, did not deteriorate with all his smoking and drinking and insomnia. It did change in timbre over the years but for most of the time, Frank could sing the Great American Songbook better than anybody on earth.

I want to tell this remarkable story as though for the first time. If you are a newcomer to Sinatra and know little of his background, I can guarantee you will be exhausted just by reading about it. Imagine living it or even worse living with him. It was like being perpetually in a storm. Maybe Sinatra’s greatest achievement is not what he did but the fact that he did it – his energy, determination and ability is remarkable.

Frank Sinatra has been under my skin for years as I’ve always been fascinated by him. I have spoken to scores of musicians, songwriters, fellow performers, fans and even the Mob about him, and their stories and reflections appear throughout the book along with the results of my research. I have made a point of listening to all his official recordings, and tracked down as many of his media appearances as I could find. I have watched all his films – some of which made me cringe, but never mind. Although I knew many of the films and records already, I wanted to see everything afresh and where possible, in chronological order, as I felt the story would benefit from this. If you want, you can undertake this journey with me, all you need is the internet. You can hear any of Frank’s records on YouTube or Spotify without cost and even many of his films can be viewed in full for free.

Please remember as you read the story that Frank could not see into the future: he didn’t know what would happen on the next page – and very often it took him by surprise.

Given Frank Sinatra’s famed loathing of the press, I found many more interviews than I expected. Some, like his famed Playboy interview, were ghosted, although he would have signed it off. His infamous, inflammatory barbs about the rock’n’roll explosion of the 1950s were also ghosted but it is clear from his private conversations that they reflected his thoughts. Although he later worked rather uncomfortably with Elvis, he never apologised for calling him ‘a cretinous goon’. Indeed, he probably never changed his opinion.

Given the fact that Sinatra gave relatively few in-depth interviews, his stage performances provide a valuable alternative source for what he was thinking. Frank Sinatra didn’t know that his concert in Blackpool in 1953 was being recorded and so he can never have expected his comments to travel outside Lancashire. They are deliciously indiscreet and tell us a lot about him and his relationships. Hearing one show after another, particularly in Las Vegas, is by no means tiresome as you are never sure what he is going to say next. Indeed, in his later years, he would even programme a seven-minute rap into his set, mainly to regain his breath but also to comment on whatever was on his mind. In this regard, he and Elvis were similar. On the other hand, Dean Martin, who cultivated his image of a lovable lush, gave very little away on stage; he rarely finished a song, let alone an anecdote.

What makes an entertainer want to be so frank with his public? Is it just egotism or is it that, as he got older, he realised that there were experiences about living that he wanted to share with his audience? Whatever, once you know the Sinatra story and the personalities involved, a seemingly throwaway remark can resound with meaning.

There is one huge plus in telling Frank Sinatra’s story. As far as I can tell, once he was a celebrity, he never did anything alone, so, over the years, there have been several friends, lovers, employees and acquaintances who have told it how it was. Even though some of their memories may have been exaggerated, a consistent picture emerges, and having read so many books and articles, I think I can determine what is true and what isn’t.

I hope I have written this biography objectively, though my opinions will intrude from time to time. Hardly surprising, given the subject matter. So sit back and relax, and enjoy this rollercoaster of a life story from a safe distance. If life is strange, then few have been stranger than Frank Sinatra’s.

CHAPTER 1

New York, New York

‘I am not Italian. I was born in Brooklyn.’ Al Capone

I. Italian-Americans

Frank Sinatra is a classic rags to riches story, a classic rage to riches story too. He was born in poverty to immigrant parents in Hoboken, New York in 1915 and he died in 1998 worth at least $200,000,000 – and probably a whole lot more too. In between he became the most famous singer in the world with successes like ‘I’ll Never Smile Again’, ‘Young At Heart’, ‘I’ve Got You Under My Skin’, ‘All The Way’, ‘Strangers In The Night’, ‘My Way’ and ‘New York, New York’. He won an Oscar for his role in From Here To Eternity and starred in High Society, Ocean’s 11 with his so-called Rat Pack, and one of the definitive war films, Von Ryan’s Express.

Frank Sinatra’s passport said he was American but he certainly felt that he was a man with dual nationality and often his Italian roots were of prime importance. Mostly, and certainly musically, this was beneficial, but he was often associated with the Mafia and these connections came close to destroying his career as well as making him behave erratically. Frank Sinatra was fond of saying, ‘I’m a victim because my name ends with a vowel.’ This is overstating the case, as there are plenty of successful Italian singers with no known connection to organised crime.

One thing is certain: his Italian background and his torrid relationship with his mother gave him a warped view of the world. Time and again in this book, you will see Sinatra making a decision, with the choice of going down one path or the other, and he invariably chooses what any reasonable person would say was the wrong one. But we are talking about Sinatra and in a funny kind of way, it was always the right path for him. The whole of his life was a crapshoot.

You can also be sure that when everything was going right for Sinatra, he would find a way to mess it up. Whatever he was doing, he wanted to move on to the next project, so anecdotes about his impatience, bad temper and intolerance are legion. He would learn his lines for a film script and want to make it single takes, an approach which set him at loggerheads with Marlon Brando when they were making Guys And Dolls.

This book describes how Frank Sinatra operated, thought and lived and much of that was filtered through his Italian background. Before we get onto his life, it worth having a potted history of Italy and finding out how so many Italians came to be in America.

There is nothing unusual about dual identity in America. Millions of Americans in his era came from first or second generation immigrant stock and while many of them regard themselves as American first and foremost, some regard their heritage as equally significant. The further somebody is from their immigrant ancestors, the more American they feel. On the other hand, the film director, Frank Capra, although born in Palermo, Sicily, in 1897, would always refer to himself as American.

After the fall of the Roman Empire in the fifth century AD, Italy became politically fragmented until unification in 1861. In that sense, the country is younger than America. Not that there has been much consistency since that unification. Although Italy is a major European country with a population of over 60 million, it often acts like a banana republic.

For centuries, Italy has been a tourist destination and the Grand Tour would not have been so grand without Venice or Rome or even Florence or Verona. Thomas Cook would have been proud of the slogan, ‘See Naples and die’, which dates from the 18th century. The Rat Pack equivalent, taking into account the many voluptuous and tempestuous Italian actresses, was ‘See Nipples and die.’

Italy is famed for its historical buildings, many of them not commercialised. However, not much money has been spent on preservation and many sites are in ruins and even appreciated for it such as Pompeii and the Coliseum. But their neglect is not solely down to time, as artisans have been chipping away bits for their own use. After Leonardo da Vinci had painted his mammoth fresco The Last Supper, the Pope, making home improvements, wanted a door just by Christ’s feet. In more recent times, the nightclub by the Spanish Steps which was featured in La Dolce Vita (1960) has become a McDonald’s.

The most debauched and evil period in Italy’s history was in the late 15th century when it had a Borgia pope. The TV series with Jeremy Irons as the scheming Pope Alexander VI drew many parallels with the Mafia, one of its subheadings being ‘The original crime family’. Pope Alexander VI was able to quell foreign invaders and indeed, all who opposed him. The Borgias were Spanish, which weakens the argument that the Italians are genetically programmed for such destructive behaviour.

In 1796 Napoleon invaded Italy, intending to capture it for France. His stock fell when he met his Waterloo in 1815, leaving Italy as a loose collection of states, run by the Pope, the Habsburgs and the Bourbons. Political turmoil and revolts led finally to unification in 1861, when Victor Emmanuel was crowned king. Giuseppe Garibaldi was considered the darling of fashionable society in England but opinions about him are mixed. Was he a champion of the oppressed or did plant the seeds which led to Europe’s dictators? In some circles, he is only remembered by a biscuit.

In the 19th century there was a huge nautical trade bringing cotton from America to Europe and the ship owners wondered what they could transport on the outward journey and the answer was people, hundreds of thousands of them. The ships hadn’t been built for passengers and the journey could take several weeks with the possibility of disease as the travellers were crammed in tight. Because times were hard, millions of people were prepared to endure hardships and risk their lives in order to reach America.

America called itself ‘the land of the free’ and the Statue of Liberty in New York harbour, which was a gift from the people of France in 1886, welcomed immigrants with open arms, but the prospects were not good. There was plenty of room, but there were no financial handouts or housing benefits for the arrivals.

The first settlers went to mining towns but the later ones opted for an urban existence in the developing huge conurbations of New York and Chicago. Close to New York, Hoboken was taken from the name of a city in Belgium, so it is reasonable to assume that the Flemish had some say in its name. It was founded by John Stevens in 1784 and he established a ferry service across the Hudson River between Hoboken and New York. At first, Hoboken became home for many German and Irish immigrants. The large waterfront included a recreational area and New Yorkers would go there for Sunday picnics. When Charles Dickens came to America in 1842, he commented on how busy Hoboken was. In 1855 Hoboken became a city in its own right.

Meanwhile, Italy was a country in crisis: it was in debt and badly managed with poor roads and widespread poverty, especially in the south. Over the years a gulf had developed between the urban north and the rural south. On the map, Sicily, the largest island in the Mediterranean, looks like a football being kicked by the mainland and that is how it felt for the inhabitants.

Sicily had been the cause of one of the bloodiest conflicts in ancient history. It had originally belonged to the Greeks but they lost it to Carthage in Tunisia. Carthage with its teeming city, booming port and extensive trading empire could be seen a template for New York.

With the help of mercenaries, the Romans gained control of Sicily in the First Punic War (264–241 BC). The Carthaginians then moved into Spain and Hannibal destroyed several Roman armies. Hannibal hoped to regain Sicily but in 146 BC, Rome destroyed Carthage, fearing that the armies might rise again.

Sicily has a population of around five million, and yet an extraordinary number of players in this biography are of Sicilian extraction: Frank Sinatra and his family, Louis Prima, Frankie Laine, Vincent Minnelli, Liza Minnelli, Frank Capra, Joe DiMaggio, Sonny Bono, Cyndi Lauper, the author of The Godfather, Mario Puzo and a real life godfather, Sam Giancana. To them, we can add the bodybuilder Charles Atlas, Al Pacino, Martin Scorsese, Sylvester Stallone, Frank Zappa, Jon Bon Jovi and Lady Gaga. Sicily rules, OK?

But back in the 19th century, Italy’s problems were magnified in Sicily. The landowners controlled the jobs and many working men felt that they were forgotten or disregarded. A self-help group, the Fasci, was formed to resist their oppression. Fasci means a bundle or sheaf. The implication was that you might be able to break a single stick, but you couldn’t break a bundle. This has a direct link to rise of Italian fascism in the 1920s. Strikes, violence and arson were commonplace in Sicily. The Fasci Siciliani was dissolved in 1894 and over 1,000 members were forcibly deported. As a result, the poor were even more demoralised and many were desperate to emigrate.

Italy’s strongest asset, its good agricultural land, was being wasted through overuse. Amongst Italy’s drawbacks were its volcanoes. Mount Vesuvius hasn’t erupted since 1944 but it can’t be much fun living in its shadow.

The country’s politicians were often inefficient and corrupt and there were food shortages and mass unemployment. This has meant that Italians have great allegiance to their family and friends, seeking support from and helping those around them. Because of the poverty, many Italians wanted to leave the country and set up new lives for themselves and their families abroad.

Emigration from Italy started on a small scale around 1850 and in the next 40 years around half a million Italians went to America. Then, between 1890 and 1914, 4 million Italians went to America. As the ships sailed into New York harbour, the immigrants would see the Statue of Liberty and cheer, but when they landed at Ellis Island or Castle Garden they were confused and bewildered. They were given medical tests and, if satisfactory, were allowed into the country. They brought their belongings with them but their possessions were often stolen within hours of arriving in America. The now derogatory term of ‘wop’ comes from the immigration process where it stands for ‘without papers’. They were living on their wits and it was survival of the fittest.

Many of the Italians joined the Germans and the Irish in Hoboken. As elsewhere, the hatred between the different communities was occasioned by fear, the thought that these people were not like us with their different cultures, languages and religion. One positive result of this bigotry was that the Italians from the north and south, although rivals in their homeland, felt they had to bond in this new land. Paul Anka says, ‘The Irish were Frank’s natural enemies when he was in Hoboken so he was always a bit suspicious of them.’ We will see how this plays out in Sinatra’s relationship with the Kennedys.

A portrayal of the racism of the time can be seen in D W Griffith’s film, The Birth of a Nation (1915). Although acclaimed as an early cinematic masterpiece, it was effectively a long commercial for the Ku Klux Klan, whose members at the time hated all immigrants.

Hoboken became a major transatlantic port and in 1917 became the embarkation point for American forces going to Europe. This was when America dropped its neutrality by joining the Allies. The Government originally thought that it wasn’t their fight but then many Americans lost their lives with the sinking of the Lusitania in 1915.

There was a slogan, ‘Heaven, Hell or Hoboken by Christmas’. By seizing the docks for military use, less revenue came into the city, and for one very good reason: the authorities had closed all bars within half a mile of the port. The German parts of the city were placed under martial law and many Germans were incarcerated at Ellis Island.

It was a difficult time for German-Americans, but the First World War gave some hope to Italian-Americans. The USA did not enter the war until 1917 and the American casualties have been placed at 50,000, far fewer than the loss in Vietnam. Nevertheless, many Italian-Americans had fought for the USA, some being wounded or killed, and they had earned the right to be called Americans. Hoboken was no longer dominated by the Germans as they had lost their standing. Two Jewish-German immigrants, Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II, set their 1929 Broadway musical, Sweet Adeline, in a beer garden in Hoboken in 1890, although it did not have a score to match their earlier success, Show Boat.

Of the four million Italians, mostly from southern Italy, who settled in America, most did not want to farm as they thought the land might again be overused. Those who did want to farm settled around New Orleans, but the majority wanted to live in the cities. Most of them were illiterate so were forced into manual work – any manual work would do. Frank Sinatra said of his forefathers, ‘They took any kind of job and you know why? So their kids wouldn’t have to do those jobs. So I wouldn’t have to do it.’

Or as Tony Soprano told his therapist: ‘When America opened the floodgates and let us Italians in, what do you think they were doing it for? Because they were trying to save us from poverty? No, they did it because they needed us – they needed us to build their cities and dig their subways and make them richer.’ His shrink responds, ‘That might be true, but what do poor Italian immigrants have to do with you?’

In Italy, the padrone system operated: the boss would find employment for the workers. The padrone system could work but at the extremes, it became the Mafia, and it came to America. The word mafia is a Sicilian word for ‘daring’, itself taken from an Arabic word for ‘bragging’. Although associated with organised crime, the Mafia was respected as well as feared in the community. They could bribe police, judges and politicians. They could curry favour and solve disputes. The aim was to make as much money as possible, no matter what it took.

The American Mafia did not become a social problem until Prohibition in the 1920s and with the advent of such gangsters as Al Capone, turf wars and gangland killings became commonplace. Generally speaking, the Mafia refers to Italian gangsters, while the Mob widens the term to include Jewish and Irish gangsters. There is a code of honour with the Mafia – they look after their own, hence the Italian word omertà.

The families often had legitimate businesses as a front: one owned its own funeral parlour where special coffins with false bottoms were manufactured so that two people could be buried at once. It’s hard to make a conviction stick if you can’t find the body. Once the families moved to Las Vegas, it was easy to lose bodies in the desert.

In 1891 in the Catholic part of New Orleans, several Italian immigrants were accused of murdering a corrupt policeman, David Hennessy. Nineteen were charged with the crime but several were not tried and the rest were acquitted. For the first time, the press talked of the Mafia, a society which conferred hidden powers to a relative handful of hoodlums, bound by blood oaths. It was suggested that the Mafia had bought off the jurors. There was a public outcry and 11 of the accused were killed, mostly lynched or shot. The press didn’t criticise their behaviour and Sinatra was to comment, many years later, ‘We’ve been there too, man. It wasn’t just black people hanging from the end of those ropes.’ Indeed, the Italians were not seen as Caucasians and were often despised A tv movie about this lynching, Vendetta, starring Christopher Walken, directed by Nicholas Meyer, was made in 1999.

Italians also came in large numbers to America after the Great War and huge family communities were established. Although cholera was largely eradicated through better sanitation, one of the Italian areas became a focal point for polio and they were blamed, unfairly, for the disease. The Italians didn’t mingle much with other groups as they formed friendships within their communities. They had pride in who they were. Gianni Russo, the adopted son of the Mafia leader, Frank Costello, told me, ‘I have nine sons and every Italian thinks he can sing and can make love. I thought I could do those too but I tell my kids not to do them at the same time. (Laughs)’

Dozens of American cities had their Little Italys; apart from Hoboken, there was a Little Italy around Mulberry Street in nearby Manhattan. These areas were based around their old culture and the residents could speak Italian all day if they wished. They lived in cramped conditions with several to a room. The police were hostile and the newspapers derided them. They clung to their faith, the vast majority being Roman Catholics, and they concluded that it was still better than what they left behind.

There was the clichéd image of the Jews as clever and wealthy, the blacks as athletic and sexually potent, and the Italians as criminals and psychopaths. Curiously, the Jewish singer, Al Jolson found international fame by wearing blackface, while the Jewish comic actor, Chico Marx, made his reputation by imitating Italian-Americans. He used his comic accent for mispronunciations and malapropisms. In Animal Crackers (1930) Groucho Marx asked his brother, ‘Hey, how did you get to be an Italian?’ Good question.

The Italians were associated with gangsters and anarchists, the gangster image persisting to this day. Even if not criminal, the immigrants were regarded as hot-headed and temperamental. In the late-1920s, an Italian-American, Tony Lazzeri, became a very successful baseball player; it was unusual to find an Italian excelling in this most American of sports. Lazzeri also had a secret – he was epileptic but fortunately he never had a seizure on the field.

In 1922 Mussolini turned Italy into a fascist state, and he made his peace with the Pope in 1929 with the creation of Vatican City. When Mussolini entered the war on the German side against Britain and France in May 1940, Churchill gave the order to ‘collar the lot’ with reference to the Italian immigrants in the UK. These poor men and women – tailors, hairdressers, shop owners – were imprisoned on the Isle of Man or sent to Canada, without any thoughts for human rights. When Mussolini announced that Italy was at war against America in December 1941, the US government had a much more difficult problem, as there were millions of citizens of Italian origin already established there.

President Roosevelt had antipathy towards Italian-Americans and he asked the head of the FBI, J Edgar Hoover to draw a list of anyone who was a threat to national security. Consequently, Sinatra’s mother could not understand why her son supported Roosevelt.

Many Italian-Americans joined the armed forces and some ended up fighting their blood relatives. There were severe losses of Italian lives when the ships, Arandora Star and Laconia, were torpedoed. Italy was invaded by the Allies in 1943, and many Italian-Americans must have nursed mixed feelings. Mussolini was imprisoned and Italy did an about-turn and declared war on Germany. In 1945 Mussolini and his mistress were shot dead by communist partisans and their bodies were hung from meat hooks at a local petrol station in Milan, where they were defiled by the public.

In 1946 Italy became a republic and for a few years, all was well as Italy was a founder member of NATO and the European Union. However, its internal politics returned to pandemonium and often the residents neglected to pay their taxes with no official action being taken. In the 1990s there were allegations of corruption in public office and it was as though the country had learnt nothing from its history. The upshot has been short-lived governments and constant turmoil, and Silvio Berlusconi with his bunga bunga parties became the laughing-stock of Europe.

Today there are nearly 300 million people living in the USA. Over 50 million people have German ancestry, which is the largest group, followed by 40 million African-Americans, largely descended from the slaves. Those of Italian origin number 18 million and the race has certainly punched above its weight in terms of the arts, fashion and cuisine: by now pizza is as American as apple pie.

A director of the Grammys, Bob Santelli, says, ‘I am an Italian-American, born a mile and a half from Frank and it is very hard to shake off this Mafia image. The image may have become worse as The Sopranos shows the Italian immigrants in the worst light possible. My grandfather was born in Italy, but my father was born here and he said that we had to call ourselves Americans and not Italian-Americans. I couldn’t take Italian at school as he told me to choose another language. We were Catholic though and my grandmother had three pictures in her house, Pope John XXIII, John F Kennedy, the first Catholic president, and Frank Sinatra. The blessed Trinity.’

Although there has now been a black President and Oprah Winfrey has become one of the richest Americans, there is still considerable racial tension in many cities, which was exposed by the O J Simpson trial in the 1990s, and continues to be exposed on a regular basis given the police shooting unarmed black people in recent times. This undercurrent of one community not wanting to be associated with another is played out in all manner of ways in the Frank Sinatra story.

When a concert was staged to celebrate Frank Sinatra’s 80th birthday in 1995, Bob Dylan, of Russian-Jewish stock, chose to perform his little-known ‘Restless Farewell’. Dylan had written the song when he was only 23 but the whole song encapsulates Sinatra’s life: the chaotic spending, too much booze, treating women badly, ignoring bad press and being true to your code. The defiant ‘I’ll make my stand and remain as I am’ could have come from ‘My Way’ and ‘I’ll bid farewell and not give a damn’ would have been Sinatra’s preferred way of saying goodbye. It’s a brilliant song and the most significant verse relates to racial tension; Dylan makes the pertinent observation, ‘Every foe that ever I faced, The cause was there before we came’ – in Sinatra’s case, being of Italian origin in America. Sinatra never sang this song and he might not have picked up on Dylan’s diction, but it’s the best song ever written about Sinatra, even though Dylan presumably wrote it about himself.

II. Day In–Day Out, 1915–1934

From an archivist’s standpoint, the record-keeping at Ellis Island was not all that it should have been, and assumed or incorrect names were often recorded. We do however know that over 200 people called Sinatra (or something similar) arrived at Ellis Island between 1892 and 1910, but it’s not possible to pinpoint the entry date for all of Frank Sinatra’s grandparents into America.

The Latin senex means ‘old man’ and senatus stood for the ‘senate’, so the wise elders of a land came to known as senators. The name ‘Sinatra’ evolved as a corruption of this. It was the perfect surname, distinctive but not too much so, and ironically, having ‘sin’ as the first syllable. In view of Frank Sinatra’s eminence, it is surprising that very few children have been christened Sinatra. Sinatra Presley sounds as good a stage name as Elvis Costello.

Francesco and Rosa Sinatra lived in Lercara Friddi in the province of Palermo, Sicily, and their son, Frank’s father, Antonino Martino (known as Marty) was born on 4 May 1892. As it happens, a Mafia boss, Lucky Luciano, who figures in this story, was born in Lercara Friddi in 1897.

Francesco picked grapes for a living and thought he could do better in America. He sailed to Hoboken and worked first as a boilermaker. Then he moved to the American Pencil Company, making a reasonable $11 a week. In 1903 he was joined by Rosa and her two sisters. In time, Rosa was able to open a little grocery store.

In the 19th century, the port of Genoa was prosperous, and Sinatra’s maternal grandfather worked there as a lithographer. Sinatra’s maternal grandparents, the Garaventes, sailed to America and settled in Hoboken. Their daughter was called Natalina because she was born on Christmas Day 1895. They gave her the nickname, Dolly; she had blue eyes and stayed petite, being five foot and weighing seven stone.

Marty worked for a shoemaker but he felt that he might have more success boxing, a sport then more associated with the Irish than the Italians. Because he had blue eyes, he felt he could pass himself off as an Irishman and so he fought as Marty O’Brien. Marty met Dolly in 1912 and they were soon an item. As boxing was a male sport, Dolly would dress as a boy and attend his fights.

There was still some prejudice about northern Italians dating southerners, but Dolly was determined to marry Marty. Her parents said no; Marty was from Sicily, he was illiterate, he had tattoos, but the fact that he was a boxer was not a drawback as Dolly’s two brothers, Dominic and Lawrence, were also fighters.

They married without parental approval at Jersey City Hall on Valentine’s Day 1913. Marty listed his occupation as an athlete. Both families were outraged: in their view, a marriage ceremony had to be conducted by a priest. The families soon accepted their commitment and a priest married them the following year. Marty and Dolly lived at 415 Monroe Street, one of eight families in the tenement.

Frank Sinatra was born at home on 12 December 1915. As Dolly was small, it is surprising that he weighed nearly a stone at his birth. The doctor used forceps for a breech delivery, not too efficiently as he damaged the baby’s neck, cheek and ear as well as puncturing his eardrum. He wasn’t breathing and he might just have been another stillborn baby but Rosa had other ideas. She held him under the cold water tap until he breathed. Dolly told Marty, ‘That’s my Christmas present to you. We can’t afford anything else.’

In 1955 Frank told Peggy Connolly, a singer he was dating, that ‘they were just thinking about my mother. They ripped me out and tossed me aside.’ Because of the permanent marks on his left jaw, he was called Scarface by his school friends and the doctor was the first person he ever wanted to beat up (but he never did). Although he was nowhere near as precious as some Hollywood stars, he preferred to be photographed from his right side.

Because of the complications of the birth, Dolly was unable to have further children. So Frank was an Italian rarity: an only child. The birth certificate says Francis Sinestro (sic), no doubt a clerical error, with no mention of Albert. Having the wrong name officially recorded bugged Sinatra and in 1945, a sworn affidavit from Dolly declared that the intended name was Francis A Sinatra, though Albert was still not given in full. On the birth certificate, Marty gave his occupation as chauffeur, but he was still fighting.

Dolly was still recuperating and not well enough to attend her son’s christening at St Francis Roman Catholic Church in Hoboken on 2 April 1916. With a view to stepping up in the world, his godfather was Frank Garrick, a family friend who worked for the Jersey Observer and was a nephew of the Hoboken police captain. The priest asked Garrick his name, thinking him the father, and continued by christening the baby, Frank. So he was christened Frank Sinatra, and again no Albert. Recordkeeping was slapdash: the 1920 census shows the family as Tony, Della and Frank Sonatri.

The young child had plenty of relations living nearby. Both sets of grandparents were alive and there were five uncles, three aunts and twelve cousins. A second cousin, Ray Sinatra, who had been born in Sicily in 1904, was to become, independently of Frank, an arranger and conductor. He was Mario Lanza’s musical director but he had few dealings with Frank, and only worked with him occasionally.

Dolly had been hoping for a girl and often dressed Frank in pink baby clothes. As he grew up, Dolly gave him the smartest clothes she could afford, which Frank later likened to Little Lord Fauntleroy. She associated dirt with poverty and she instilled in Frank the need to be fastidiously clean.

Although Dolly had a day job in a sweet factory, she found time to help the local community, often reading letters from home for illiterate Italians. She spoke English well and knew the various Italian dialects so she provided invaluable help with legal matters such as citizenship papers.

The politicians in Hoboken were impressed by Dolly’s personality and saw how she could be used to attract voters. She became politically motivated, campaigning for the Democrats, and even chained herself to the city hall railings in 1919 in support of women’s suffrage.

The US Temperance Movement had been advocating prohibition and the legislation for banning alcohol was passed in 1919 across much of America. The intention was that the population would sober up. It was the craziest legislation imaginable but perhaps the drinkers were too busy drinking to combat the prohibitionists.

Producing alcoholic drinks was one of the biggest businesses in America; now this was all declared illegal. Prohibition came into effect on 16 January 1920. The saloons held farewell parties, giving the last rites to John Barleycorn. Only it wasn’t over. The law only encouraged an underground world of mobsters and bootleggers, and illegal drinking clubs, known as speakeasies, opened up. It wasn’t difficult to bribe corrupt officials who would ignore what was happening. As Frank Sinatra commented, ‘The Mob was invented by those self-righteous bastards who gave us prohibition. It was never going to work.’ Not true, but it certainly made the Mob more powerful.

Alcohol was also used for paint thinning, antifreeze and had many other uses. The Government warned that such products must not be consumed, but many citizens were drawn to poisonous cocktails.

There were thousands of illicit stills and the mobsters added gambling and prostitution to the mix. F Scott Fitzgerald’s 1925 novel, The Great Gatsby, romanticises bootleggers, although the source of Gatsby’s own wealth is unknown. Many of the key figures such as Al Capone were evil and highly dangerous. Al Capone was known as Scarface, though not, of course, to his scarred face. It is highly probable that Joe Kennedy, the patriarch of the Kennedy family, made some of his wealth by illegally importing spirits into Boston with the help of the Mafia, but Joe was too clever and too manipulative to be caught. Kennedy invested some of his capital in the 1926 silent film, Rose of the Tenements, which was about New York gangsters.

In 1921 Dolly’s brother Lawrence, who fought as Babe Sieger, was arrested for driving the getaway car in an armed robbery which left a railway worker dead. He could have been executed so he was fortunate to receive 10 years hard labour.

Also in 1921 Marty decided that he’d had enough. He had fought 30 professional fights, sometimes losing and after both breaking his wrist and being knocked out, he wanted to retire from the ring. He had a short spell as a boilermaker but the working conditions exacerbated his asthma. For a time, he worked for some bootleggers by collecting whiskey from Canada. However, having suffered a head injury while protecting his cargo he looked for something more stable.

As a result, Dolly borrowed some money from her family and they bought a bar on the corner of Jefferson and Fourth called Marty O’Brien’s, although it was officially listed as a restaurant. A noted bootlegger Waxey Gordon (real name Irving Wexler) was a regular customer who replenished their stock of illegal booze.

Marty was not a perfect landlord but he could keep order. He was grouchy and didn’t enter into small talk with the customers, but he liked practical jokes. Once at a friend’s house, he slipped him a laxative after spreading glue on the toilet seat. Another time he took a sick horse to a rival saloon and shot it dead in the doorway. Not only does this have echoes of The Godfather but this paragraph could have been written about his son. But, as we shall see, it was Dolly’s personality that really matched Frank’s.

Dolly was always scheming and could be abusive and vengeful. She once pushed Frank downstairs, knocking him unconscious, and she often beat him with a small truncheon. She dunked his head in the ocean, an incident which led to him becoming an expert swimmer. ‘My mother had the most wonderful laugh. She was wonderful,’ he would say, but he both sought her out and avoided her in equal measure. It’s possible that some of Frank’s attitudes towards women came from his upbringing. Possibly he learned to trust no one because of his mother’s outlook.

Like mother like son when it came to foul language. Dolly was surprisingly uninhibited for a woman in the 1920s and her favourite expression was ‘son of a bitch bastard’.

Sometimes Dolly would sing in the bar; one of her favourite songs, ‘When Irish Eyes Are Smiling’, was in keeping with the Irish pseudonym. There is a photograph of Dolly holding a guitar in 1925 so presumably she knew some basic chords.

While Marty and Dolly were managing the bar, the young Frankie might be left with a neighbour. One was the Jewish Mrs Golden, from whom he assimilated some Yiddish phrases which occasionally drifted into his stage act.

In the early 1920s it was possible to buy radios fairly cheaply. Although a family might not be able to afford theatre tickets, they could hear Enrico Caruso or the Paul Whiteman Orchestra in their living rooms. You could argue that Caruso was the key performer in establishing gramophone records; Bing Crosby then introduced intimate singing through a microphone; Sinatra encouraged the sale of LPs; Elvis 45rpm singles; the Beatles rock albums; Queen stadium rock; Dire Straits compact discs; and Radiohead downloads. It’s simplistic, but there you have it: the history of popular music in one sentence.

The young Sinatra was entranced by what he heard and from 1924 onwards, he would sit on the piano in the bar and sing in his unbroken voice for customers. He favoured ‘Honest and Truly’, a ballad written by Fred Rose, the co-founder of the music publishing giant, Acuff-Rose. He was also singing in the choir at St Francis.

Marty’s cousin Vincent Manzola had been wounded in the First World War and he came to live with them in 1926. He was shell shocked and slow-witted, but he held down a job on the docks, where he was called Citrullo, the Italian term for blockhead. He was another of Dolly’s problems but he did bring extra income into the house.

Another unwelcome nickname was attached to Marty’s wife: Hatpin Dolly. She was a trained midwife and was known for walking around with her little black bag. Living in a Roman Catholic community, abortions were not officially allowed in any circumstances, but Dolly set herself up as the local abortionist. She saw herself as saving local embarrassment, but she was arrested in both 1937 and 1939, the second time just after Frank’s first wedding.

In 1927 Dolly used her influence to secure Marty a job with the Hoboken fire brigade, which was very much an Irish domain. Marty was able to bypass the written test. This meant that there were three incomes in the household and they moved from 415 Monroe Street to a flat ten blocks away: 705 Park Avenue. It had three bedrooms, cost $65 a month and was a step up the social ladder – they were now living in a German/Irish neighbourhood.

Frank was scrawny but healthy, his only operation being an appendectomy when he was twelve. He was mocked by his classmates in the David E Rue Junior High School for his short temper. He didn’t enjoy being taught, and did poorly, but he shielded this from Dolly by purloining a blank report card and completing it himself. His most mischievous stunt was to release some pigeons during the school play, Cleopatra, which led to his expulsion in 1928. He signed on briefly at the Stevens Institute, the oldest college of mechanical engineering in the US, and located in Hoboken. His friends called him Slacksy O’Brien because he had so many trousers.

Frank had his own room and he would listen to his Atwater Kent radio. Radio was recognised as the most important form of communication; two key networks had started broadcasting: the future giants NBC (1926) and CBS (1927). Frank would dream of singing over the radio.

One of his favourite songs was Irving Berlin’s ‘Oh! How I Hate to Get Up in the Morning’, a theme that resonated with his own life. The song was introduced by Eddie Cantor and popularised through a hit recording by Arthur Fields. Bing Crosby’s crooning appealed to him and he loved jazz bands, especially Louis Armstrong’s. The jazz musicians would sometimes take liberties with the original melodies, something which horrified Jerome Kern, who wanted his songs performed as they had been written. Frank approved of this free and easy approach to a song and, as we shall see, sometimes the songwriters did not approve of Frank did with their songs.

As everyone who attends pub quizzes knows, the first ‘talkie’ was The Jazz Singer, starring Al Jolson, but it was anything but a jazz film. The story concerned a young singer from an immigrant family who defies his parents as they only want him to sing in the synagogue. Jolson, who sang schmaltz with exaggerated mannerisms, has few followers today, but his repertoire was amazing: ‘Alexander’s Ragtime Band’, ‘Swanee’, ‘California Here I Come’, ‘Sonny Boy’ and ‘Mammy’, the last two being idealised pictures of family life which Frank would hardly recognise. Jolson started wearing blackface because his dresser had told him, ‘You’d be much funnier, boss, if you blacked your face like mine. People always laugh at the black man.’ At the time, nobody thought Al Jolson’s approach was offensive.

Although The Jazz Singer was immensely successful and at the forefront of new technology, it was also dated as Al Jolson had not modified his approach following the introduction of stage microphones in 1924. He still sang as though he was bellowing to the back of the stalls. Now Bing Crosby had developed his crooning style with immaculate diction and a laidback, friendly approach. In other words, the voice on records was sounding more like a normal voice. Frank pinned his picture on his bedroom wall and once Dolly threw a shoe at Frank and hit the picture. Frank would impersonate the way he sang. ‘Every time Bing sang on the radio,’ said Frank, ‘it became a duet and I was the other singer.’

There is a wonderful story, probably apocryphal but worth telling. Around 1930 Bing Crosby was in Hoboken and was arrested for being drunk. Sinatra couldn’t believe his luck: Bing was in the local jailhouse! He went over there and found the cells were in the basement with windows at street level. Sinatra located where Bing was being held and Bing responded with a ‘Go away, kid.’ If that’s not true, it certainly should be.

His uncle Dominic had given him a ukulele but he didn’t take the instrument seriously. Frank never mastered a musical instrument nor read music, although he could play a few notes on the piano and a few chords on the guitar. Whenever he could, he would see Jascha Heifetz play violin. He had no wish to play the violin but he was intrigued by the way that Heifetz could hold notes and sustain them. Almost without thinking, his own vocal style developed from that. He would improve his diction by watching films starring Clark Gable and, from 1932, the British actor Cary Grant, the George Clooney of his day. A reporter once told Grant, ‘Everybody wants to be Cary Grant’ and he replied, ‘So do I’.

Unlike Jolson, Rudy Vallée, the star most associated with megaphones, adapted well to the new techniques. He became the host of one of the first variety shows, The Fleischmann Hour on NBC. He had a major success with ‘The Stein Song’, the rights of which were bought by NBC, an early example of a media organisation moving into associated fields.

In 1930 Marty was fed up with Frank hanging around the house. Rather like Aunt Mimi with John Lennon, he told him, ‘Go out and get a job, but no singing.’ Admittedly, this was a tough order during the Depression when there were over four million unemployed in the US. Although a job didn’t materialise, he did go to New Jersey and sing in a bar. The song he chose was ‘Am I Blue’ which Ethel Waters sang in the film, On with the Show. He was paid with cigarettes and a sandwich.

In 1931 Frank enrolled at the A J Demarest High School and his parents had hopes that he would settle down and train to be an engineer. No such luck; Frank lasted 47 days. Sinatra’s lack of a formal education was his own fault, but he became self-conscious about it and this insecurity manifested itself from time to time.

The family moved to a three storey house with four bedrooms and central heating at 841 Garden Street, effecting a mortgage for $13,000. Dolly bought Frank a used Chrysler convertible for $35. He kept himself fit by pitching in an amateur baseball team, his favourite sport; his team wore orange and black, his favourite colours.

Frank loved gangster films, his favourites being Little Caesar (1931) with Edward G Robinson and Scarface (1932) with Paul Muni. Both actors were playing a character based on Al Capone, but neither actor was of Italian origin. Sinatra saw the gangsters as romantic figures like Robin Hood, and he was to develop this thought into a Rat Pack film. Oddly, the craze for gangster films was short-lived as the 1933 film code banned ‘bigotry or hatred among people of different races, religions or national origins’. This reduced the number of Italian gangsters on screen, but certainly one young Italian-American did not see them that way. Bing Crosby, who was invariably diplomatic, did once let slip that ‘I think Frank has always had a secret desire to be a hoodlum.’

Meanwhile, the real life gangsters were having a hard time. Al Capone was inside for, of all things, tax evasion, and Legs Diamond was shot to death in his hotel room.

Also in 1931 Bing Crosby had a huge success with his radio show for CBS and had one of the biggest hits of his career with ‘Just One More Chance’. The following year he appeared on the same bill with Bob Hope at the Capitol Theatre on Broadway. They worked a few light-hearted routines together, which cemented their partnership.

Meanwhile Frank was still being coerced into finding regular employment. In 1932 he had a terrifying job at the Teijent and Lang shipyard in Hoboken. He had to catch hot rivets while swinging on a harness 40 feet in the air. He dropped one which singed his shoulder and it scared him so much that he left. He had lasted three days and he was still only 16.

After that he was unloading books for a publisher in Manhattan and then back on the docks for a nightshift in the dead of winter. His job for United Fruit Lines was to remove parts of the condenser units, clean them and restore them. He hated the dirt and he hated the drudgery.

Then Dolly had a brainwave. She went to the Jersey Observer to ask Frank’s godfather, Frank Garrick, now the circulation manager, to give him a job. For a short while, he bundled newspapers onto delivery trucks, but Frank wanted to be a sports writer. When one of the sports journalists was killed in an accident, Dolly demanded that Frank take his job. Very foolishly, she instructed Frank to sit at his desk. Bad move. The editor asked what he was doing and he said, quite wrongly, that Mr Garrick had given the post. The editor sacked him. Frank was furious – he was always angrier when he knew he was wrong – and he blamed Garrick for not supporting him. Dolly was equally furious and never spoke to Garrick again.

In 1933 Bing Crosby sang the lighthearted and gently self-mocking ‘Learn to Croon’ in the film, College Humour, and Frank was soon performing the song with a megaphone (as microphones were expensive) in little bars and clubs. The patrons would throw cents into the funnel. This was way out-of-date and he persuaded Dolly to spend $65 on a portable public address system in return for him performing at some local meetings for the Democrats. He was a Bing Crosby tribute act as he sang ‘Please’, ‘Just One More Chance’ and ‘I Found a Million Dollar Baby’, but he also included an impression of Jimmy Cagney in the gangster film, Public Enemy.