Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Grove Press UK

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

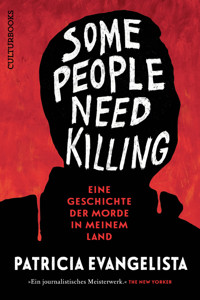

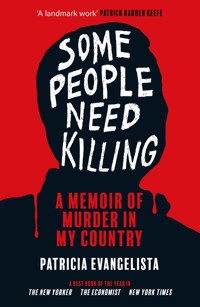

LONGLISTED FOR THE WOMEN'S PRIZE FOR NON-FICTION ONE OF THE NEW YORK TIMES' BEST BOOKS OF 2023 ONE OF THE ECONOMIST'S BEST BOOKS OF 2023 ONE OF THE NEW YORKER'S BEST BOOKS OF 2023 ONE OF BARACK OBAMA'S BEST BOOKS OF 2023 TIME MAGAZINE'S #1 NONFICTION BOOK OF THE YEAR 'A journalistic masterpiece' David Remnick, New Yorker My job is to go to places where people die. I pack my bags, talk to the survivors, write my stories, then go home to wait for the next catastrophe. I don't wait very long. Journalist Patricia Evangelista came of age in the aftermath of a street revolution that forged a new future for the Philippines. Three decades later, in the face of mounting inequality, the nation discovered the fragility of its democratic institutions under the regime of strongman Rodrigo Duterte. Some People Need Killing is Evangelista's meticulously reported and deeply human chronicle of the Philippines' drug war. For six years, Evangelista chronicled the killings carried out by police and vigilantes in the name of Duterte's war on drugs - a war that has led to the slaughter of thousands - immersing herself in the world of killers and survivors and capturing the atmosphere of fear created when an elected president decides that some lives are worth less than others. The book takes its title from a vigilante whose words seemed to reflect the psychological accommodation that most of the country had made: 'I'm really not a bad guy,' he said. 'I'm not all bad. Some people need killing.' A profound act of witness and a tour de force of literary journalism, Some People Need Killing is also a brilliant dissection of the grammar of violence and an important investigation of the human impulses to dominate and resist.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 674

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise for

SOME PEOPLE NEED KILLING

TIME’S #1 NONFICTION BOOK OF THE YEAR

A NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW TOP 10 BOOK OF THE YEAR

WINNER OF THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY’S HELEN BERNSTEIN BOOK AWARD

FINALIST FOR THE CHAUTAUQUA PRIZE

LONGLISTED FOR THE WOMEN’S PRIZE FOR NON-FICTION AND THE MOORE PRIZE

NAMED A BEST BOOK OF THE YEAR BY THE NEW YORK TIMES, THE NEW YORKER, THE ECONOMIST, CHICAGO PUBLIC LIBRARY, CRIMEREADS, THE MARY SUE

“[Patricia] Evangelista makes us feel the fear and grief that she felt as she chronicled what Duterte was doing to her country. But appealing to our emotions is only part of it; what makes this book so striking is that she wants us to think about what happened, too. She pays close attention to language, and not only because she is a writer. Language can be used to communicate, to deny, to threaten, to cajole. Duterte’s language is coarse and degrading. Evangelista’s is evocative and exacting.”

—The New York Times

“A powerful story of disillusionment . . . Evangelista seamlessly segues from her own life story into a riveting police procedural. . . . [Her] book is an extraordinary testament to half a decade of state-sanctioned terror. It’s also a timely warning for the state of democracy.”

—The Atlantic

“It is a cliché to compare such writers to George Orwell or, more lately, with justice, Martha Gellhorn. But, if the shoe fits . . . [Evangelista] has written a journalistic masterpiece. She is a very rare talent.”

—The New Yorker

“One of the most harrowing and brave books published this year . . . [Evangelista is] unflinching in bearing witness to the thousands of dead killed under Duterte’s reign of terror, which he claimed was largely focused on drug dealers and users, but which wreaked havoc on almost every part of Filipino society.”

—Time

“Evangelista has written an intense, emotional lamentation for the thousands of suspected drug pushers, users, and innocent victims—including children—extrajudicially executed by corrupt cops and vigilantes during the rule of Filipino president Rodrigo Duterte from 2016 to 2022.”

—Foreign Affairs

“This is not just a documentation of the drug war, but a history of the Philippines; an account of what brought Duterte to power; and a rumination on what it is like to be a journalist covering brutal atrocities.”

—The Irish Times

“A rigorously reported look at Rodrigo Duterte’s campaign against illegal drugs.”

—The Economist

“[Evangelista] is both chronicler and agent, witness perhaps not to the killing itself but to the larger crime of its planning and the exoneration of its perpetrators. Handling the most sensitive and dangerous of material, she draws on more than skill to tell her story; she demonstrates raw courage, an increasingly rare quality among journalists easily seduced and silenced by pragmatism. She names names, which surely will bear consequences both ways.”

—The Philippine Star

“Searing, searching . . . [a] harrowing, thoughtful, absorbing account . . . Evangelista, in the field, looks for the telling detail or the outrageous fact; at her writing table, she looks for the enabling word, the language that kills.”

—Rappler

“Beyond the thoroughness of the reportage, Evangelista’s gift as a writer shines as much as her grit as a journalist; she is not a third person reporting facts with professed objectivity, but a first person, feeling, grieving, fearing, hoping against hope, struggling, as we all (must) do, with her positionality as a person of relative privilege amid such suffering.”

—Philippine Daily Inquirer

“Among the most compelling works of our era—not only a magisterial work of passionate journalism, but also a wrenching investigation into how Asia’s oldest democracy succumbed to one of the most inhumane policies of the twenty-first century.”

—The Interpreter

“In this shattering debut, Filipina journalist Evangelista interviews detainees, families, and key government officials to illuminate the Philippines’ brutal war on drugs. . . . With rigorous reporting, Evangelista painstakingly lays out how Duterte gathered political power and convinced his constituents to support the slaughter. Most chillingly, she speaks to several ardent Duterte followers and allies who’ve come to regret their support for the ex-president, who left office in 2022. The result is an astonishing and frightening exposé that won’t soon be forgotten.”

—Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“Analytical, ambitious, and told with empathy, this will stand as a definitive historical account of the Philippines’ drug war.”

—Booklist (starred review)

“A landmark work of investigative reporting by a writer of formidable courage . . . Patricia Evangelista’s searing account is not only the definitive chronicle of a reign of terror in the Philippines, but a warning to the rest of the world about the true dangers of despotism—its nightmarish consequences and its terrible human cost.”

—Patrick Radden Keefe, New York Times bestselling author of Empire of Pain

“Completely astounding, and beautifully written, Some People Need Killing is a priceless act of documentation. Patricia Evangelista’s account of Rodrigo Duterte’s so-called drug war, and the conditions that made his regime possible, is one of the bravest things I have ever seen committed to paper. As each devastating page shows, the horrors of this war will echo for years to come.”

—Jia Tolentino, New York Times bestselling author of Trick Mirror

“Tragic, elegant, vital . . . Patricia Evangelista risked her life to tell this story.”

—Tara Westover, New York Times bestselling author of Educated

“Patricia Evangelista exposes the evil in her country with perfect clarity fueled by profound rage, her voice at once utterly beautiful and terrifyingly vulnerable. In short, clear sentences packed with faithfully recorded details, she reveals the nature of unbridled cruelty with a relentless insightfulness that I have not encountered since the work of Hannah Arendt. This is an account of a dark chapter in the Philippines, an examination of how murder was conflated with salvation in a violent society. Ultimately, however, it transcends its ostensible subject and becomes a meditation on the disabling pathos of self-delusion, a study of manipulation and corruption as they occur in conflict after conflict across the world. Few of history’s grimmest chapters have had the fortune to be narrated by such a withering, ironic, witty, devastatingly brilliant observer. You may think you are inured to shock, but this book is an exploding bomb that will damage you anew, making you wiser as it does so.”

—Andrew Solomon, National Book Award–winning author of Far and Away

“In this haunting work of memoir and reportage, Patricia Evangelista both describes the origins of autocratic rule in the Philippines and explains its universal significance. The cynicism of voters, the opportunism of Filipino politicians, the appeal of brutality and violence to both groups—all of this will be familiar to readers, wherever they are from.”

—Anne Applebaum, Pulitzer Prize–winning author of Twilight of Democracy

“The story of what has happened in the Philippines is the story of what is happening in the wider world, as people turn to autocracy, lured by the false promise of security and belonging. Some People Need Killing is a beautiful, gripping, and essential book that paints a picture of how autocracy takes root. Through dogged reporting, extraordinary courage, and exquisite storytelling, Patricia Evangelista has written a book that is definitive on its subject while transcending it. Read this book to understand the times we are living in and to be inspired by Evangelista’s relentless insistence on uncovering the truth and revealing our common humanity.”

—Ben Rhodes, author of After the Fall

“This is a magnificent, brave book about the extrajudicial murders in the Philippines under Rodrigo Duterte. It is written in taut, powerful prose . . . one of the most important books I’ve ever read.”

—Suzannah Lipscomb, chair of the Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction

“Heartbreaking personal stories underscore the consequences of a government-incited extrajudicial rampage.”

—Kirkus Reviews

First published in the United States in 2023 by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York

This paperback edition first published in Great Britain in 2025 by Grove Press UK, an imprint of Grove Atlantic

Copyright © Patricia Maria Susanah Chanco Evangelista, 2023

The moral right of Patricia Evangelista to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of the book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

No part of this book may be used in any manner in the learning, training or development of generative artificial intelligence technologies (including but not limited to machine learning models and large language models (LLMs)), whether by data scraping, data mining or use in any way to create or form a part of data sets or in any other way.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN 978 1 80471 008 1

E-book ISBN 978 1 80471 007 4

Printed in Great Britain

Grove Press UK

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.groveatlantic.com

This book is dedicated to the survivors of the drug war, named and unnamed, who have chosen to bear witness.Without their courage, this record would not exist.

What I want to do is instill fear.

—MAYOR RODRIGO ROA DUTERTE

Contents

Prologue

PART I: MEMORY

1: Positive

2: The Surviving Majority

3: Mascot for Hope

4: The Rise of the Punisher

5: Defend the Mayor

PART II: CARNAGE

6: Salvation

7: How to Identify an Addict

8: How to Kill an Addict

9: My Friend Domingo

10: Some People Need Killing

11: Djastin with a D

12: My Father Is a Policeman

PART III: REQUIEM

13: Acts of Contrition

Epilogue: We Are Duterte

Acknowledgments

Notes

Prologue

Every day, for a period of a little more than seven months beginning in 2016, the Philippine Daily Inquirer maintained what it called the Kill List. It was a public record of the dead, fed by reports from correspondents across the country. The circumstances of death were brief. The entries were numbered and chronological. The locations were limited to towns, cities, and provinces, without the specificity of street addresses. Names were recorded when they were available, numbers were used when they were not.

The first “unidentified suspected drug pusher,” for example, was killed on July 1, the first day of Rodrigo Duterte’s administration, the same morning that Jimmy Reformado, fifth most wanted drug pusher in the city of Tiaong, was shot by “unknown hitmen.” The next day, July 2, Victorio Abutal, the most wanted drug pusher in the town of Lucban, was “killed by unknown hitmen in front of his wife” an hour and ten minutes before the death of Marvin Cuadra, second most wanted, less than fourteen hours before the seventh most wanted, Constancio Forbes, was “killed at close range outside a lottery betting station.” A day later, on July 3, Arnel Gapacaspan, the most wanted drug pusher of San Antonio, was killed “by unknown hitmen who barged into his house” at exactly the same time that Orlan Untalan, tenth most wanted in Dolores, was “found dead in a spillway, body laden with bullet holes.”

“Unknown hitmen” was a common phrase, but it was the nature of their victims—suspected drug pusher, suspected drug dealer, at large on drug charges, on the local drug list, most wanted—that demonstrated that what was occurring was far from random. These were targeted killings, as President Duterte had promised, directed against “people who would threaten to destroy my country.”

The methods were limited only by the killers’ imaginations. There was the man “found dead after being abducted from his house.” There were the three “found dead in a canal, blinded and hogtied.” There was the man “shot in the head in his bedroom” and the man killed at seven in the morning “in front of his daughter’s elementary school.” The daily death toll sometimes rose to double digits, as it did on July 9, beginning at midnight with a suspected drug dealer’s aide named Danilo Enopia Morsiquillo, who was shot as he slept beside his girlfriend. The twelve other deaths that day varied in means and disposition. One, a former overseas worker, was shot as he drove down the highway. Two were found strangled under cardboard boxes with signs calling them criminals. Three others were found dead with “gunshot wounds to the head and mouths covered with packing tape.” The rest were drug suspects—“killed by unknown hitmen.”

None of these deaths were officially at the hands of the police. If the government was to be believed, these killings had been committed by private citizens and members of drug cartels, some of whom used the war as a cover to silence possible informants.

The constancy and sheer velocity required its own nomenclature. They were drug-related deaths. They were illegal killings. They were targeted assassinations, salvagings, body dumps, drive-by shootings. They were “casualties in the Duterte administration’s war on crime,” or, as the news network ABS-CBN would put it, “those who perished.” Even Philippine officials seemed unable to agree on the terminology. One senator called them “summary killings.” The interior secretary called them “alleged vigilante-style killings of drug personalities.”

There is language for this phenomenon. The term is “extrajudicial killings.” It was the single phrase that became commonplace on the street and on television, so common that a Senate resolution called for sessions investigating “the recent rampant extrajudicial killings and summary executions of criminals.” The repetition forced a shorthand—EJK. The press used it as a qualifier. The victims’ families used it as a verb. The critics used it as an accusation.

From the beginning of the Duterte era, recording these deaths became my job. As a field correspondent for Rappler in Manila, I was one of the reporters covering the results of the president’s pledge to destroy anyone—without charge or trial—whom he or the police or any of a number of vigilantes suspected of taking or selling drugs. The volume of Duterte’s dead was at times overwhelming, as was covering the powerful in a country where the powerful refuse to be held to account.

I ran away halfway through the war.

At the time, I was investigating a series of killings in the capital. It was slow work. I hunted down witnesses. I culled official reports. I met men who detailed the precise manner in which they killed their own neighbors on orders from above, then sent interview requests to the police officers they accused. Rappler decided my presence in Manila was a security risk. I agreed. It was safer to assume that the self-interest preventing vigilantes from shooting me on sight was unlikely to hold. My editor delayed publication until my plane lifted off the tarmac.

All this was why I found myself crossing the Pacific in early October 2018. If the good people of the Logan Nonfiction Fellowship believed I could produce literature, I was happy to pretend I could. The residency was three months long at a wooded estate in upstate New York. It should have come as a relief, but years of covering a state-sanctioned massacre does odd things to the mind. I had learned to qualify every statement and to burn transcripts on my balcony. I had lain awake nights convinced that a misplaced comma could be grounds for criminal libel. For someone with my sort of obsessive imagination, the practical caution required of a drug war reporter morphed into an almost paralyzing paranoia. Nothing was certain. Everyone was lying. The man with the selfie stick was a spy for the cops, or a killer, or a fanatical supporter of the president likely to upload my photo of meeting a source on to Twitter.

The fact that I was occasionally correct fueled the lunacy. Many things were suspect: white vans, flashing lights, spam emails, men on motorcycles, automated credit card transactions, the waiter at the coffee shop, the hotel clerk asking for my billing address, a ringing phone, a dropped call, the doorbell. I read and reread my own stories, hunting for gaps, agonizing over sentence construction, convinced I had missed the error that would get a witness killed. By the time I stood at JFK airport, blank disembarkation form in hand, I couldn’t trust my memory to write out my own name. I verified the spelling against my passport. I remember distinctly the compulsion to find a second source—and found it, in my birth certificate.

The Albany countryside was a pretty place, even if a pack of cigarettes did cost thirteen dollars a pop. It was cold. People were warm. There was chocolate mousse for dessert, sometimes berries. I spent most of the first weeks trying to disappear into a fog of Star Trek and Agatha Christie, but the residency required I make an honest attempt at producing a book proposal. I did. I wrote about who I was, and where I came from, and what it was like to stand over a corpse at two in the morning.

I signed with a publisher at the end of the residency, committing to a first-person account of the Philippine drug war. It happened fast. I didn’t intend to lie. That promise of intimacy was a distant thing, discussed inside a glass-walled conference room one winter morning, thousands of miles away from the heavy heat of a Manila under the gun.

I went home. I began to write. The first draft was a carefully detailed 73,000 words describing the circumstances of every death, the crime scenes so many and so thick on the page that it wasn’t possible to distinguish one corpse from the next. It was reportage, cold and precise. Nowhere did I say who I was, or where I came from, or what it was like to stand over a body at two in the morning.

Journalists are taught they are never the story. As it happened, the longer I was a journalist, the better it suited me to disappear behind the professional voice of an omniscient third person, belonging everywhere and nowhere, asking questions and answering none. Every conclusion I published was double-sourced, fact-checked, and hyperlinked. My name might have been below the headlines, but the stories I wrote belonged to other people in other places, families whose grief and pain were so massive that mine was irrelevant.

All this is true, but it is also true that I was afraid. My inability to hold myself to account was due not only to a misguided commitment to objectivity. It was a failure of nerve.

This is a book about the dead, and the people who are left behind. It is also a personal story, written in my own voice, as a citizen of a nation I cannot recognize as my own. The thousands who died were killed with the permission of my people. I am writing this book because I refuse to offer mine.

—Manila, June 2023

I

MEMORY

1

POSITIVE

My name is Lady Love, says the girl.

The girl is eleven years old. She is small for her age, all skinny brown legs and big dark eyes. Lady Love is the name she prints on the first line of school papers and uses nowhere else. It was her grandmother who named her. Everyone else calls her Love-Love. Ma did, when she sent Love-Love to the market. Get the children dressed, Love-Love. Don’t bother me when I’m playing cards, Love-Love. Quit lecturing me, Love-Love.

Nobody calls her Lady, and only Dee ever called her Love. Just Love.

Love, he would say, give your Dee a hug.

Dee is short for Daddy. It embarrasses Love-Love sometimes, not the hug, because Dee gives good hugs, but that she calls him Dee. Only rich girls call their fathers Daddy. Pa should be good enough for a girl who lives in the slums of Manila. But there they are, Dee and Love, Love and Dee, walking down the street in the early evening, the small girl stretching up a scrawny arm to wrap around the tall man’s waist.

Love-Love was supposed to be the third of eight children, but the oldest died of rabies and the second was rarely home. It fell to Love-Love to tell Ma to stop drinking and Dee to quit smoking. You’re drunk again, she would tell Ma, and Ma would tell Love-Love to go away.

Love-Love worried they would get sick. She worried about rumors her father was using drugs. She worried about all of them living where they did, in a place where every other man could be a snitch for the cops.

Ma and Dee said everything was fine. Dee was getting his driver’s license back. Ma made money giving manicures. They had already surrendered to the new government and promised they would never touch drugs again.

Let’s move away, Love-Love told Dee, but Dee laughed it off.

Let’s move away, she told Ma, but Ma said the little ones needed to go to school. We can go to school anywhere, Love-Love said.

Ma shook her head. They needed to save up first. Don’t worry yourself, Ma said.

Love-Love worried, and she was right.

Love, said her father, one night in August.

Love, he said, just before the bullet slammed into his head.

I meet her at her aunt’s. She is sitting on a battered armchair. I crouch in front of her and stick out my hand to shake hers. If nothing else, an interview is an exchange. Tell me your name, and I’ll tell you mine.

My name is Pat, I tell Love-Love. I’m a reporter.

I was born in 1985, five months before a street revolution brought democracy back to the Philippines. That year it seemed every other middle-class mother had named her daughter Patricia. Evangelista, my surname, common in my country, derives from the Greek euangelos, “bringer of good news.” It is an irony I am informed of often.

My job is to go to places where people die. I pack my bags, talk to the survivors, write my stories, then go home to wait for the next catastrophe. I don’t wait very long.

I can tell you about those places. There have been many of them in the last decade. They are the coastal villages after typhoons, where babies were zipped into backpacks after the body bags ran out. They are the hillsides in the south, where journalists were buried alive in a layer cake of cars and corpses. They are the cornfields in rebel country and the tent cities outside blackened villages and the backrooms where mothers whispered about the children that desperation had forced them to abort.

It’s handy to have a small vocabulary in my line of work. The names go first, then the casualty counts. Colors are good to get the description squared away. The hill is green. The sky is black. The backpack is purple, and so is the bruising on the woman’s left cheek.

Small words are precise. They are exactly what they are and are faster to type when the battery is running down.

I like verbs best. They break stories down into logical movements, trigger to finger, knife to gut: crouch, run, punch, drown, shoot, rip, burst, bomb.

In the years since the election of His Excellency, President Rodrigo Roa Duterte, I have collected a new handful of words. They rotate, trade places, repeat in staccato.

Kill, for example. It’s a word my president uses often. He said it at least 1,254 times in the first six months of his presidency, in a variety of contexts and against a range of enemies. He said it to four-year-old Boy Scouts, promising to kill people who got in the way of their future. He said it to overseas workers, telling them there were jobs to be had killing drug addicts at home. He told mayors accused of drug dealing to repent, resign, or die. He threatened to kill human rights activists if the drug problem worsened. He told cops he would give them medals for killing. He told journalists they could be legitimate targets of assassination.

“I’m not kidding,” he said in a campaign rally in 2016. “When I become president, I’ll tell the military, the police, that this is my order: find these people and kill them, period.”

I know only a few dozen of the dead by name. It doesn’t matter to the president. He has enough names for them all. They are addicts, pushers, users, dealers, monsters, madmen.

Love-Love can name two of them. They are Dee and Ma.

It was a blow that started it, on the wrong door, just down the hall. There was a commotion, fists on wood, tenants protesting, and door after slammed door, punctuated by a man’s voice.

Negative, said the man. Negative, negative, negative.

It didn’t take long for the man to reach Love-Love’s door. Open it, shouted the man.

Inside, Love-Love crouched with her mother. It was three in the morning. Dee was fast asleep on his back, one of the toddlers tucked into his chest. The other children slept scattered around the room. The man kicked the door.

This, Love-Love thought, was how her parents would die.

Her mother opened the door, afraid the men outside would punch through the window and kill them all in a hail of gunfire. Two men burst into the room. Both wore full masks, with holes for eyes and nose and mouth.

“Positive,” one of them said, looming over Dee. Get up, he said.

Dee jerked awake. He tried to sit up, but there was a baby curled into his chest. He fell back again.

Love, he said, before one of the men shot him dead. The bullet burst out of Dee’s right temple. Blood spattered over the baby.

“Dee!” Love-Love screamed.

The baby wailed. Ma wept. She thrust a handful of paper at the man who killed her husband. Here was proof, she sobbed, that they had mended their ways.

Ma fell to her knees. Love-Love dragged her mother up until she was on her feet. It was Love-Love who squeezed her body between the gunman and Ma. It was Love-Love who stood with the barrel of the gun just inches from her forehead. It was Love-Love, all big eyes and skinny brown legs, who cursed at the gunman and demanded he shoot her instead.

Kill me, she said, not my Ma.

The second gunman held back the first. Don’t shoot, he said. She’s only a child.

They left. It wasn’t for long. When they returned, the first gunman turned back to Love-Love’s mother and raised his gun.

“We are Duterte,” he said, and emptied the magazine.

Ma died on her knees.

Love-Love cursed at the killers. You motherfuckers, she said. You already killed my Dee. Now you’ve shot my Ma.

The gunman swung the muzzle at Love-Love’s face.

Shut up, he said, or we’ll shoot you dead too.

When they left, Love-Love found the hole inside Ma’s head. The blood gushed through Love-Love’s fingers. Dee lay where he fell. His eyes had rolled back. Love-Love wanted to hug him, but she was afraid. He did not look like her Dee.

“Dee,” asked the girl called Love. “Are you leaving me, Dee?”

In 1945 the reporter Wilfred Burchett broke the story of a nuclear warhead exploding over the city of Hiroshima for the London Daily Express. He covered what he called “the most terrible and frightening desolation in four years of war.” Burchett marched into Hiroshima carrying a pistol, a typewriter, and a Japanese phrasebook. “I write these facts as dispassionately as I can,” wrote Burchett, “in the hope that they will act as a warning to the world.”

Like Burchett, I am a reporter. Unlike him, I’m not a foreign correspondent. I spent the last decade flying into bombed-out cities, counting body bags, and reporting on the disasters, both natural and man-made, that continue to plague my own country. And then came the last six years of documenting the killings committed under the administration of President Rodrigo Duterte.

The fact that I’m a Filipino living in the Philippines means that for me, there’s no going home from the field. There is no seven-day shooting schedule with a pre-booked flight and an option to extend; only more corpses, every day. I do not need a translator to tell me that the man screaming putang ina over his brother’s body means “motherfucker” instead of “son of a bitch.” I understand why coffins sit in living rooms for weeks at a time, and I’m ready to refuse, with all manner of excuses, when I am offered a sandwich at a wake by a widow so desperately poor she cannot afford the twenty-dollar formaldehyde injection necessary to preserve a rotting body.

There were corpses every night at the height of the killings. Seven, twelve, twenty-six, the brutality reduced to a paragraph, sometimes only a sentence each. The language failed as the body count rose. There are no synonyms for blood or bleed. The blood doesn’t gush by the time I walk into a crime scene. It doesn’t burble or spurt. It sits in pools under doorways or, as in the case of the jeepney barker shot in front of a 7-Eleven, streams out of the mouth in rivulets.

Dead is a good word for a journalist in the age of Duterte. Dead doesn’t negotiate, requires little verification. Dead is a sure thing, has bones, skin, and flesh, can be touched and seen and photographed and blurred for broadcast. Dead, whether it’s 44 or 58 or 27,000 or 1, is dead.

I record these facts as honestly as I can, but I am not dispassionate as I set them down. That I am Filipino also means I understand guilt, in the complicated way only a Catholic raised in the colonized Philippines knows guilt. I know why a father kneels to wash away his son’s blood while muttering apologies into the linoleum. I know he believes himself responsible for failing to stop the four bullets that burst through his thirty-year-old son’s body: forehead, chest, and narrow shoulders, in a manner he sees as the sign of the cross—in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit, amen. I know all this because I am my father’s daughter and understand that while my survival is a privilege, my own father prays too.

President Duterte said kill the addicts, and the addicts died. He said kill the mayors, and the mayors died. He said kill the lawyers, and the lawyers died. Sometimes the dead weren’t drug dealers or corrupt mayors or human rights lawyers. Sometimes they were children, but they were killed anyway, and the president said they were collateral damage.

I saw many young girls in the first months of the war, and not all of them survived to tell their stories. In the same week that Love-Love’s parents were killed, a five-year-old girl named Danica Mae was shot with a bullet meant for her grandfather.

I spoke to him inside a cramped cement room where the face of Jesus Christ looked benignly down from a wall calendar. His name was Maximo, and he didn’t attend his granddaughter’s funeral. His family told him to keep away. His daughters promised they would take video on their phones. Wait for it on Facebook, they said. Wait for the funeral video, we’ll make sure you can watch. He understood why he shouldn’t go, and why his family had taken him straight from the hospital to a house far from where he had lived most of his married life. The men in masks could come back to the house and finish the job. Nobody would go to visit his Danica Mae. He wanted Danica surrounded by her mourners. She deserved it, and so much more.

Maximo had supported the Duterte candidacy. He still wore the red-and-blue baller band with the president’s name stamped in white. Maximo had voted for Duterte because Duterte was a strong man. It didn’t matter that Maximo had used drugs himself. Maybe Danica would have died even without Duterte in the palace, or maybe she wouldn’t have. All he knew was that there had been many deaths, some of them men on the same list where his name had been found. The list called him a drug dealer.

“Let them come and kill me if they can,” he said. “I leave it to God. God knows who the sinners are, and who is telling the truth.”

So he waited alone, a big man with a hard, heavy belly and red-rimmed eyes. He cried a little, prayed a little, cleaned what bullet wounds he could reach. He called Danica’s parents and told them to lean over her coffin and whisper that her grandpa loved her.

He told them to say he stayed away for her.

Until the year President Duterte was elected, I considered myself the most practical sort of cynic. I understood that terrible things happen to good people. I took a morbid pride in the fact that I belonged to that special breed of correspondent for whom it was possible to stand over a corpse and note that the body in the water was probably female, that there were remains of breasts under the faded yellow shirt, despite the fact the face above the shirt was missing skin and flesh.

If my journalism had a moral hierarchy, uppermost was that the loss of a life was the worst of all things, to be avoided at all possible instances. The concept wasn’t revolutionary. I was raised a citizen of the oldest democracy in Southeast Asia, and I believed, as I thought most of my generation did, in free speech and human rights and the duty to hold my government accountable. I believed in democracy in 2009, when I reported on the murders of thirty-two journalists. I believed in it in 2013, when I covered the bombardment of Zamboanga City. I believed in it in 2015, after government arrogance sent forty-four unsuspecting policemen into a cornfield to die at the hands of rebels. I believed in democracy much the same way I believed in short sentences and small words.

Democracy, like murder, is a simple word. I saw it as a general good opposed to a general wrong. By democracy, I did not mean the elected administration. The government, every government, failed often, was complicit often, was by and large incompetent, hypocritical, and out of touch. The democracy I believed in was the nation, a community of millions who saw brutality as an aberration to be condemned as often and as vigorously as necessity demanded.

I still believed in democracy when I began counting President Duterte’s dead. I didn’t understand that the democracy my journalism depended on was particular only to myself and a minority of others. Elsewhere in the country, people died, starved, or were widowed or orphaned or ignored. In the world as imagined by Rodrigo Duterte, that nation was a crowd of idiots and innocents, set on by crooks and thugs. His nation was the badlands, where the peace was broken, no citizen was safe, and every addict was armed and willing to kill.

Duterte had your back, and he said the struggle ended here, today. Fuck the bleeding hearts. To hell with the bureaucracy. There would be no forgiveness, there would be no second chances, the line would be drawn, and on one side he would stand with a loaded gun. The law might be optional, the thugs might be at the helm, but Duterte was a man who said what he meant and meant what he said, who might give you a warning and then count one, two, three.

This was the Republic of the Philippines that Rodrigo Duterte promised to save. Give him six months, and there would be an end to crime and corruption. Give him six months, and there would be an end to drugs.

He was applauded, celebrated, and in the end, inaugurated.

“Hitler massacred three million Jews,” he said. “Now there are three million drug addicts. I’d be happy to slaughter them.”

In December, five months into the war, another little girl saw her father die. Her name was Christine, and she was fourteen.

One day, she said, the cops came looking for Pa. They found her mother instead. The cops called Christine’s mother an addict. She was eight months pregnant. They took her away in a white van. When Pa came home, everyone told him to run. The police, said his neighbors, would kill him if they found him.

Pa came home anyway, months later, late in the night. He said he missed the children. He cooked spaghetti. He sang songs. He fed the little ones by hand. He gave Christine half his cup of coffee. He told them all that he loved them and that it would be a while until he came back again.

They heard shouting from outside the house. Three guns appeared at the window, the barrels bright in the sunlight. The door burst open. Five policemen ran into the house. They had Pa kneel on the armchair and shoved his face into the back cushion. He clutched at his ID. He said he was clean.

Please, he said, please arrest me instead. I have so many children.

The police told the children to get out. Christine wrapped her arms around Pa. One of the policemen threw her against the wall.

Get out, he said.

Only Christine didn’t get out, at least not fast enough. She was there when the policeman shot her father, through the back of the head, through the chest, shot him at such close range that the next day her little brother stuck his finger through the hole in the sofa and dug out the bullet.

The police said Pa had fought back. They said he was a drug dealer. They said they had killed Pa in self-defense.

It was a long time after Pa died before Christine spoke again. Her first word was sorry. She said sorry to her grandmother and sorry to her siblings. She said sorry because she had let go of Pa on the morning he was killed. Had she held on harder, had she hugged him tighter, Pa would be alive.

. . .

My news organization, Rappler, has a funny name. My bosses made it up, from rap, for “discuss,” and ripple. They explained it on the day I was recruited on the third floor of a building along a street that flooded in the summertime. It had almost been Rippler, they said, and it would have stayed Rippler if someone hadn’t pointed out that it sounded like nipple. I laughed then. For the first few months, I prefaced every field interview by a repetition of the company name to confused sources who were used to the call signs of broadcast television—“Raffler, you say? Rapper? Rapeler?” Rappler, I would say. Rappler. Yes, you can find us on YouTube. No, I don’t work for YouTube. Eventually I would resign myself to saying the name quickly, then offering to tag their teenage nephews with a Facebook link.

I joined Rappler in the late summer of 2011. I was twenty-six years old, and while I did not believe, as Rappler did, that social media would make the world a better place, I did believe that journalism might make some headway if we tried hard enough. Rappler believed it could produce the new correspondent for the digital age, a one-woman news crew who could take photos, roll video, ask questions, live-tweet developments, file text stories, and beat the competition, all while producing an on-camera report with nothing more than an internet dongle and an iPhone on a tripod. The experiment was bound for failure, at least for me. I was the reporter who got lost on the way to the office and took half an hour to compose a single sentence. I could, as this is an exercise in memory, write about arguments over word counts and editing software and the color orange they chose for the logo. I could write about the afternoon the editors finally bought a couch after discovering one too many reporters sleeping under desks. I could write about the day I made a future Nobel Peace Prize laureate cry in frustration. It was my fault, but I still say she started it.

Those stories are all true, but what is also true is that Rappler sent me to many places where the ordinary ended with a body on the ground. Ask me for a story about Rappler, and I’ll tell you that every story about Rappler is also a story about the people who told us theirs. I’m a trauma reporter. People like me work in the uneasy space between what is and what should be. My stories offered no solutions, no proposed salvation. I did not traffic in hope. Sometimes, if we were lucky, a reader would pay for a coffin, or a new salon chair for a barber out in Guiuan who had lost his barbershop to a storm.

Every story began with the ordinary because it underscored what happened next. The blue sky before the flood of corpses. The kiss goodbye before the barrage of bullets. Once after Super Typhoon Haiyan reduced Tacloban to rubble, I sat behind a camera in front of a man who asked if I could broadcast a message to his son. I focused the lens, pressed the record button. Please come home, Edgardo said, because Papa is making spaghetti for Christmas dinner. His son was gone, likely drowned, but Edgardo tried to reach out anyway because maybe the ordinary would bring his son home.

I wrote about terrible things that happened because those things shouldn’t have happened and shouldn’t happen again. Then one day the man who would be president promised the deaths of his own citizens. The terrible became ordinary, to thundering applause.

Night after night the gunshots echoed through the slums. Those stories also began with the ordinary. I woke up, said someone’s lover, and he wasn’t beside me. I was taking a bath, said someone’s mother, when I heard the shouting. I was at home, said someone’s daughter, when the cop kicked in the door and shot my father. I wrote down what I could, and while there were many who mourned, there were also many who read about the dead and said more should die.

Rappler was barely four years old when President Duterte was elected. There were very few of us, but we did what we could to report on corruption and abuses of power, along with the war on drugs. President Duterte gave Rappler another name. He called us fake news. He said we were paid hacks. We were charged with tax evasion and cyberlibel and ownership violations. Rappler’s license to operate was revoked. It remains under appeal. Our reporters were banned from covering the president. We were threatened daily on social media. Because we were women, the threats included rape.

I published many stories, every one of them built around a corpse who had once had a name, even if all I had to go on was “Unidentified Body No. 4.” I wrote that five-year-old Danica was shot before she got to wear her new pink raincoat. I wrote that Jhaylord was his mother’s favorite, and that Angel had been carrying a Barbie doll on the night she was killed. I layered detail over detail, all of it, the color of the shoe, the tenor of the scream, the fact the dead man was wearing red-and-white bikini briefs when they stripped his body on the street.

“I’d like to be frank with you,” said the president. “Are they humans? What is your definition of a human being?”

Here is Danica Mae Garcia, Maximo’s granddaughter.

Here is Constantino de Juan, Christine’s Pa.

Here are Love-Love’s Dee and Ma.

Here is the man who killed them.

“We are Duterte,” said the gunman in the mask.

I was born in the year democracy returned to the Philippines. I am here to report its death.

2

THE SURVIVING MAJORITY

In the story my grandfather told, the first of the white men arrived on a fleet of five warships led by the Trinidad.

It was 1521. The flotilla had survived more than a year of misadventure and mutiny. The Trinidad’s captain, a bearded adventurer by the name of Ferdinand Magellan, saw a wooded island stretching across the horizon. The men of the Trinidad dropped to their knees, praised the Lord, and having run out of rum, proceeded to get well and thoroughly drunk on Bireley’s orange soda and Siu Hoc Tong rice wine.

Magellan dropped anchor. He hailed a boatload of passing natives.

“To show that his heart was in the right place,” said my grandfather, “Magellan had his steward bring him some red caps, looking glasses, combs, bells, and the sixteenth-century equivalent of what we now refer to as the zoot suit. These Magellan gave to the native chieftain, saying, ‘You won’t find these in any Sears, Roebuck catalog. They’re the very latest in what the well-dressed headhunter will wear, take them with the king’s and my compliments, and have you got any spare gold bars kicking around?’”

When I say my grandfather told Magellan’s story, I don’t mean to me, but to the people who might have purchased a book distributed by the Philippine Book Company, written by Mario P. Chanco in 1951. “The Fredding of Ferdinand Magellan” was one of a handful of folktales he had published while plying his trade as a newspaperman. My grandfather, so wrote one of his friends fondly, “indulged far too often in frivolous asides and irreverent remarks, especially as to Serious Writing.”

And so his imagined Magellan sailed farther into the archipelago that would later become the Philippine Islands. He met other natives, traded his cargo for gold and spices, until he came upon the ferocious chief of the island of Mactan, Lapulapu. Lapulapu refused to pay tribute to Magellan or swear loyalty to the Spanish king.

“Naturally,” my grandfather explained, “this made Magellan unhappy, for was he not propagating his monarch’s goodwill and blessings for the enlightenment and benefit of infidels the world over? What did it matter if the said goodwill was offered at the point of a musket? Didn’t it amount to the same thing?”

The conquistadors waded onto shore after a “terrific barrage on the beaches.” They were met by the spear-carrying men of Mactan, who “swooped down on them like avenging demons.” Magellan fell dead to a sharpened bamboo stake. His men sailed away, a broken band with only two ships of the grand flotilla surviving.

“As for Magellan,” concluded my grandfather, “he remained where the Mactan islands got him. And the moral of this tale is: next time you ask for anything, say please.”

. . .

No reader will mistake my grandfather for a historian, but his version of the time the Spanish conquistadors first sailed into the Philippines does bear a nodding acquaintance with the truth. Lapulapu of Mactan, whose warriors fired poisoned arrows into Ferdinand Magellan, delayed the Spanish invasion of the Philippines by almost half a century. Another attempt at claiming territory, by Ruy López de Villalobos, failed in 1544. Villalobos’s only success was leaving behind a name for the islands whose people had driven him out—Las Islas Filipinas, in honor of the future king, Philip the Second of Spain.

Only in 1565, with the arrival of Miguel López de Legazpi, did the islands finally fall subject to the Spanish Empire. For decades afterward, Spanish galleons unloaded soldiers and governors and tonsured friars. My people were taught to kneel before the Catholic God and suffer before his earthly envoys, but the Spanish soon discovered their new colony in the southeast was unwilling to suffer years of rape and rosaries. There were secret societies and armed revolts, quiet insurgencies and public executions. Near the end, the Spanish attempted both force and conciliation, executing a writer here, exiling a revolutionary leader there.

By the late nineteenth century, it wasn’t only the Philippines rebelling against Mother Spain. Mexico, Puerto Rico, and Cuba were also in revolt, just as Theodore Roosevelt, assistant secretary of the U.S. Navy, was agitating to expand the American frontier. In 1898 the United States declared war on Spain to protect its interests in Cuba. Hostilities spread to the edges of the waning Spanish Empire.

Here was America’s manifest destiny writ large. A 125,000-strong volunteer army marched into Santiago de Cuba. Roosevelt’s Rough Riders thundered through Las Guásimas and San Juan Hill. An armada carrying the United States’ Asiatic Squadron was dispatched to the capital of Spain’s foothold in Asia—Manila.

We did not win the war against Spain, because America claimed victory for itself.

The Battle of Manila Bay was a rout. Spanish ships sank. The rest were captured. America’s casualties were negligible.

So it was that Commodore George Dewey held the sea, but Filipinos fought on land, liberating city after city at the cost of thousands of lives. It was the tail end of years of native armed revolution. General Emilio Aguinaldo, returning from exile in Hong Kong, told his men to assemble in numbers wherever they saw the American flag fly. Americans, he said, “for the sake of humanity and the lamentations of so many persecuted people,” had extended “their protecting mantle to our beloved country.”

The Filipino armed militia formed an alliance with the United States. General Aguinaldo declared independence. Spain refused to raise the white flag to Filipinos, and America was happy to accommodate. The United States and Spain brokered a secret deal to keep Filipinos at bay and fought a choreographed battle. The Spanish flag came down. The American flag flew up. Filipino troops ringed Manila, barred from entering by their own allies.

Four months later, President McKinley demanded that Filipinos “recognize the military occupation and authority of the United States.” The treaty, signed in Paris, between the United States of America and the Kingdom of Spain, thus accounted for the sale of an entire colony at the cut-rate price of $20 million.

Rudyard Kipling, across the sea in England, wrote encouragement to the gentlemen of the new American Empire to “take up the White Man’s burden.”

Go, bind your sons to exile

To serve your captives’ need;

To wait, in heavy harness,

On fluttered folk and wild—

Your new-caught sullen peoples,

Half devil and half child.

The half-devil, half-child citizens of the short-lived Philippine Republic demanded the freedom promised by the sons of liberty. America answered with an iron fist. Insurgents were massacred. Towns were razed. William Howard Taft might have called Filipinos America’s “little brown brothers,” but soldiers on the ground sang a different song as they marched. There were occasional defections to the Filipino cause, but the African American soldiers who switched sides were executed for their principles.

So began the reign of the new American Empire, purchased by a white president of the new world from a white king of the old world.

We were Spain, and for forty-eight years after that, we were America.

My grandfather was born in 1922, twenty-four years into the American occupation. He was the great-great-grandson of a Chinese tradesman named San Chang Co, who had sailed into Manila in the mid-nineteenth century and settled down with a Filipino wife. By the time my grandfather was born to a university bureaucrat and a department store heiress, the surname had evolved into Chanco. San Chang Co’s descendants were born the English-speaking subjects of the United States of America.

Mario Chanco was the sixth of seven children. They lived on San Antonio Street, in a sprawling home with heavy furniture and walls of bookshelves. Much of the family wealth went toward the education of the younger generation. They learned Spanish at home, English in school, and Filipino everywhere else.

When my grandfather was twelve, the 73rd U.S. Congress signed the Tydings-McDuffie Act, a federal law directing the Philippines’ transition to independence. The Philippines turned from colony to commonwealth with the promise of sovereignty within ten years.

The Second World War interrupted both my grandfather’s schooling and the last years of the Philippine Commonwealth. My great-grandfather lost his job at the university after the Japanese discovered that my grandfather’s older brother, a West Point–educated army colonel, was blowing up bridges to slow the advancing Japanese. Some of the family hunkered down in the capital, selling off what was left of their land and moonlighting as ticket sellers for underground boxing matches. Others dispersed.

The family survived. Many others did not, with over a hundred thousand people killed. An “atrocity report,” filed on February 15, 1945, by a U.S. Army major in Manila illustrated the barbarity of the last months of the occupation. The major and his men had discovered eight decomposing bodies abandoned inside a suburban Manila home. Five of the adults, including two women, had been executed with their hands tied behind their backs. A baby had been bayoneted. Further investigation of the immediate neighborhood “led to an interview with a Filipino, one Mario Chanco, a neighbor of the deceased,” whom the report described as a newspaperman.

“We watched [the Japanese] enter the house,” my grandfather told the Americans. “Shortly after, we heard five shots. The rest I do not know because along with other witnesses, I fled the vicinity.”

By then, the Japanese were in retreat. My grandfather’s brother survived the Bataan Death March and returned to fight with the guerrillas, becoming commander of the 91st Engineer Battalion of the U.S. Army in the Far East.

In the immediate aftermath of Japan’s surrender, the United States of America ended its “high mission” of what it called “benevolent assimilation.” After nearly four hundred years of colonial rule, the Philippine Republic was declared a free nation, with a constitution described as “a faithful copy of the U.S. Constitution”—“a textbook example of liberal democracy.” By then, America had discovered that global hegemony did not require the costly maintenance of an entire archipelago of inconvenient not-quite-citizens, particularly if a nation was willing to offer preferential trade and military bases.

My grandfather was twenty-four years old the year the United States relinquished its colonial possession. He refused to return to university, devoting himself to journalism instead. He wrote of Philippine-American economic relations and Studebakersponsored radio musical hours and noted the influx of “brand-new automobiles, the latest fashions in men’s and ladies’ wear, a dozen shades of lipstick, and colorful fabrics of all varieties.” He hosted a radio show where he acquired the nickname Mao after his facetious questioning of politicians in a pidgin Chinese accent. He began operating a community paper and wrote fiction on the side. As a city hall reporter, he collected acquaintances from government offices, including “a trim young miss with an intriguing smile.” His writing style—which I am forced to admit involved the reckless deployment of adverbs—was described as “deceptively light” and “disgracefully humorous.” He was a founding member of the National Press Club and the first host of Meet the Press, where “his wit and tongue-in-cheek side comments kept politicians’ pomposity at a minimum.” His byline jumped from paper to paper, magazine to magazine, wandering across The Philippines Herald, This Week, the Sunday Times, Literary Song-Movie, Women’s Magazine, until he was promoted to reporter at large for the Manila Daily Bulletin.

He was, according to all who remember him, a generally pleasant man. “He was always cheerful and earnest, never tragic, petulant, or cross-eyed as Humorists are supposed to be,” wrote historian Carmen Guerrero Nakpil. “He was kind to what stray cats there were in the back alleys of Manila’s newspaper row, tender-hearted with good-looking young women, and respectful to editors. He went to Paco church regularly, editing for his parish a vaguely religious, semi-Rotarian publication called the Paco Town Crier. He dressed in the imaginative fashion then forced upon the post-liberation Filipino male. He was also an enterprising young man, eager to get ahead, always fiddling with daring little publishing projects.”

In 1955 he was named the country’s Most Outstanding Young Man in Journalism. He accepted a Fulbright fellowship in the United States. He published a digest called The Orient. The “trim young miss” he met on the city hall beat became the mother of his four children, referred to forevermore in his columns as the Beautiful Wife, capitals included.

“Chanco, more than any other newsman around, most closely resembles the public conception—thanks to Hollywood—of what a newspaperman is like,” wrote Felix Bautista for the Sunday Times Magazine. “He is bubbly, effervescent, incurably extroverted. He always has the snappy comeback, the sparkling repartee, and he has the average newsman’s flair for the wisecrack and the excruciating pun. His hands, when they are not banging away at a typewriter, are either gladhanding people in a hearty hail-fellow-well-met gesture, or are pointing the accusing finger at something, usually shenanigans in government.”

For the next few decades, he pecked out what he laughingly called “my deathless prose” for four hours every morning on his IBM Selectric typewriter. He opened a full-scale printing press, making it possible to produce his own supply of notebooks, of a size designed to fit the back pocket of his worn trousers. He smoked Rothmans after meals and Dunhills when he ran out, but he regularly kept a pack of Marlboro Reds open for when he wrote, flicking off ash every which way whenever the ashtray was out of reach. He raised his children, my mother his eldest, in a manner she remembered as largely comfortable. It was due, I am told, to the enterprise of the Beautiful Wife, a registered nurse, who was the axis of my grandfather’s rapidly turning world. The Beautiful Wife invested in land, ran a range of businesses, and hosted the parade of friends my grandfather brought home. They were a mix of journalists and politicians and environmentalists, including a former war correspondent named Benigno Aquino, Jr.

In 1965 a senator who claimed to be “the most decorated war hero in the Philippines” was elected its tenth president. His name was Ferdinand Edralin Marcos. He was neither decorated nor a war hero, but his story took years to unravel. At the end of the two terms allowed by the Constitution, in 1972, Marcos announced he was declaring martial law on the pretext of widespread violence and the Communist threat. He promulgated a new constitution and effectively made himself president for life, while systematically silencing critics and the free press.

The conjugal dictatorship of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos lasted fourteen years, with the cheerful support of the United States. Imelda danced with President Ronald Reagan and acquired several thousand pairs of size eight-and-a-half stiletto heels, along with the entirety of a Sotheby’s auction, including the brownstone housing the collection. The martial law period, as we called it, was rife with corruption, patronage, and political repression. It would result in an estimated five to ten billion dollars stolen from the national treasury, the imprisonment of 70,000, the torture of 34,000, and the extrajudicial murders of 3,240 activists. It is likely there were more.

At the time, so family legend goes, my grandfather was jailed along with dozens of political prisoners. My mother’s cousin, my uncle Boo, then a twenty-two-year-old reporter, saw all his friends arrested and promptly quit journalism: “I got away from being arrested, and I’m going to offer myself on a silver platter? No way.”

Martial law ended, on paper at least, in 1981, after international pressure on the Marcos regime. Very little changed. In its aftermath, Vice President George H. W. Bush raised a toast to Marcos: “We love your adherence to democratic principle.”