18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

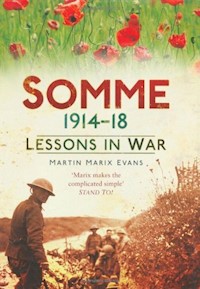

The Somme is a name with particular resonance for the people of Britain, for here, in 1916, the flower of her youth was cut down. Terrible though that day was, it takes its place in a wider story: the long, painful process of learning how to fight a new kind of war. From the war movement of 1914, when the French fought on the fields of the Somme, the conflict evolved to massive frontal assaults by the British and Allied troops in 1916. Here the first tank was first used in September 1916. Increasing sophistication in the terrifying use of artillery by the Germans broke the Allied lines in March 1918. Allied use of this same technology was then combined with other arms to create the fighting complex that inflicted the 'Black Day' on the German army in August and smashed the Hindenberg Line in September. Thus the British, Australian, Canadian, American and French forces defeated the German Army in the field at last. This book reveals how the Somme was the bloody classroom in which this new art of war was studied and it tells the story of the men who paid the price for this knowledge with their own blood.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

Somme 1914–18

Somme 1914–18

Lessons in War

Martin Marix Evans

For the women and children – Gillian,

Louise and Polly, Cherry, Ruby, Olivia, Minnie and Stanton

May they never have to endure events such as these.

First published in 2010

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2011

All rights reserved

© Martin Marix Evans, 2010, 2011

The right of Martin Marix Evans, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 80022

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 80015

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Introduction

Acknowledgements

1 First Fights on the Somme

2 A New Kind of War: 1915–16

3 The Somme 1916: The First Day

4 The Somme 1916: Experiment and Attrition

5 The Somme 1917: A False Quiet

6 The Somme 1918: Operation Michael

7 Advance to Victory: May to November 1918

8 Hindsight

Bibliography

Introduction

People of many nations fought and died on Somme battlefields – it is not only the British who revere this land. In the early days of the First World War, the Germans, French and British disputed the territory, and by British I mean the English, Irish, Scottish and Welsh. The French Army included troops drawn from North Africa and West Africa. Very soon, citizens of the British Empire arrived, from India, South Africa, Canada, Australia and New Zealand as well as the colonies and dependencies. In the later stages of the war the Americans arrived, and while their battles elsewhere have had greater attention, they also fought valiant and vital actions on this front. This diversity, and the experiences of men and women on opposing sides, is reflected in this book.

Located between Paris and Calais, Picardy and the battle theatre of the Somme are easily visited by both continental and inter-continental travellers, and here the evolution of warfare between 1914 and 1918 can be studied in full. Technical innovation was sometimes seen on the Somme for the first time and almost every new development was eventually demonstrated here. Moreover, the area is quite small; you can drive from Amiens to St Quentin by autoroute in an hour, and the same time will suffice for the north to south traverse of the region. The high-speed railway from the Channel to Paris crosses the fought-over ground. It is easy to access the Somme.

What happened on the Somme is set out, inevitably, partly with the benefit of hindsight, but an attempt has been made to show what the participants, from the bravest to the most fearful, and from private soldier to army commander, knew and thought at the time. The answers these participants found to the questions they thought they faced were in their outcome often less successful than they would have wished, but it is often possible to see why they thought that they were right at the time. It can also be seen how these questions changed and innovated in the face of terrible events. The same thinking has informed the selection of maps. All are contemporary with the events studied here. Trench maps convey a good deal about the real situation but also illustrate the perceived facts. The maps from publications of the time show the terrain, roads and railways as they existed during the war, and they can easily be related to the modern touring maps used by the visitor.

All of this brings the courage and sacrifice of these warriors into sharper focus.

Acknowledgements

Since I first wrote on this subject in 1996, new and revealing work has been published. In particular, Jack Sheldon’s research within German archives has provided another dimension to the possible appreciation of the battles of this war and I recommend his work to serious students of the conflict. The other authors to whom I have turned with particular attention for vivid impressions of the experience of the Western Front are Lyn Macdonald and Martin Middlebrook. I am grateful to Cleone Woods for permission to quote from the work of Geoffrey Malins, Ian Parker for allowing me to quote from his father’s book, Robert Burton for access to his father’s unpublished papers and to Fanny Hugill for allowing me to quote from her father’s correspondence. I have used the words actually written in the sources quoted; spelling and grammar are unaltered and the intrusive use of the word ‘sic’ has been avoided. At the time of going to press the copyright holders of some texts have not been identified, and the author would be glad of information to correct the deficiency. The greater part of the American and French material is from my own research in France and the USA, and is reproduced with the permission of the institutions detailed below and cited in the bibliography. The translations from the French are my own. In seeking to understand aspects of how the British fought, I have learned much from the work of Paddy Griffith and of Gary Sheffield.

The constructive and patient assistance of Marie-Pascale Prévost-Bault, Jean-Pierre Thierry, Frédérick Hadley, Sabine Belle and Nathalie Legrand at the Historial de la Grande Guerre (HGG), Péronne, variously over several years, of Jan Dewilde of the Documentatiecentrum In Flanders Fields, Ieper (IFF), of David Fletcher of the Tank Museum, Bovington, Dorset (TM) and his former colleague, Graham Holmes, Dr Tröger of the Bayerisches Haupstaatarchiv, Munich (BH), of Teddy and Phoebe Colligan of the Somme Association, 36th Ulster Division Tower (UT), of David Stanley and the volunteers of the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry Archives, Horspath, Oxford (Ox & Bucks) and of the staff of the Photograph Archive of the Imperial War Museum, London (IWM) is most gratefully acknowledged. Assistance in accessing and understanding the material at the US Army Military History Institute, Carlisle, PA (USAMHI) was most constructively given by Dr Richard Sommers, David Keough, John Slonaker, Michael Winey and Randy Hackenburg. Ashley Ekins and Libby Stewart made work at the Australian War Memorial, Canberra, very productive. I am deeply grateful to the late Major General Tim Cape, CB, CBE, DSP, Australian Master-General of Ordnance for his explanation of the history and officering of the Australian Imperial Force, made in a private meeting in 2002. John Kliene has contributed his picture editing skills to render various images legible, and I am most thankful for that.

The illustrations in this book are subject to copyright and are reproduced by kind permission of the institutions listed above where identified by their initials. The modern colour photographs are mine and any unannotated illustrations are from my collection. British Ordnance Survey maps of the battlefields are Crown Copyright.

Martin Marix Evans,

Blakesley, Northamptonshire,

December 2009

Chapter 1

First Fights on the Somme: 1914

On Sunday 28 June 1914 Gavrilo Princip shot and killed the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo and set in motion a chain of events that led to the outbreak of war, not only in Europe, but across the world. During the next five weeks massive armies assembled in Germany, Austria, Russia and France and lesser armies mobilised as well, including the relatively small British regular army. Roger Charlet of the French 87th Regiment of Infantry wrote home from Ham, south of Péronne, on 25 July to report that war had been declared between Austria and Serbia and that Germany was mobilising. His leave was cancelled. His 2nd Company was mobilising and being issued with field equipment. ‘I still hope to be able to come and see you,’ he signed off. Maurice LePoitevin, 329th Regiment of Infantry, was unenthusiastic on being mobilised. ‘It’s not the rehearsal the optimists think,’ he remarked.

When war broke out in the west with the German invasion of Belgium on 4 August, both adversaries, the Germans and the French, thought it would soon be over. The Germans had complete confidence in the Schlieffen Plan, the strategy of sweeping through Belgium to take Paris, while the French relied equally on Plan XVII which involved a strike to the east through Lorraine and Alsace, the lands lost in the Franco-Prussian War. Neither succeeded.

In the summer of 1914 the principal opposing forces in the West were arrayed as follows. On the German side, from north to south, were the First Army, 320,000 men under General Alexander von Kluck, north of Aachen, and the Second Army, 260,000 men under Field Marshal Karl von Bülow, facing Liège and southern Belgium, poised to tackle the forts at Liège and Namur, while the more northerly force was to thrust westwards at all speed. The plan was hugely ambitious as the distance to be covered by the First Army, passing east of Lille and Amiens to envelop Paris, demanded much from an army reliant on horse-drawn transport and marching men. The Third, Fourth, Fifth, Sixth and Seventh Armies were to hold territory to the south. The Third, 180,000 men under General Max von Hausen, and Fourth, 180,000 men under Albrecht, Grand Duke of Württemberg, were to advance between Rheims and Verdun, while the Fifth, 220,000 men commanded by Crown Prince Wilhelm of Prussia, would surround the iconic stronghold above the river Meuse. The Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria had the 220,000 men of the Sixth Army and General August von Heeringen the Seventh, 125,000 men, to attack on the Moselle and in the Vosges mountains.

The French Fifth Army with 254,000 men spread itself from Sedan in the direction of Maubeuge on the river Sambre, between Valenciennes and Charleroi and was commanded by General Charles Lanrezac. Lieutenant Edward Spears, 11th Hussars, had been attached to the French War Office that summer, and, bring fluent in French, was now with the Fifth Army as liaison officer. The British Expeditionary Force (BEF), 103,691 men under Field Marshal Sir John French, commenced embarkation on 9 August and by 20 August was concentrated at Maubeuge. In Belgium the 117,000-strong army under King Albert, stood from Namur to Diest on the river Gette, but two divisions were sent forward to protect the fortified areas of Namur and Liège, an awkward deployment which was directly attributable to Belgian reluctance to be seen as allies of France. The Belgian forts were garrisoned only by some 90,000 men. Usually forgotten is the space between the BEF and the coast. On 14 August 1914 a Territorial Divisions Group was formed under General Albert d’Amade. It consisted of three divisions, the 81st, 82nd and 84th, comprised of older men, unfit for front-line service and known to regulars as ‘grandads’. Their task was to protect the railways against possible raids by enemy cavalry on a front that was not expected to see serious action.

To the east the French had four armies numbering 817,000 men in all. The First was commanded by General Auguste Dubail, the Second by General Noël de Castelnau, the Third by General Pierre Ruffey and the Fourth, east of Sedan, by General Fernand de Langle de Cary.

Sir John French, arrived to meet General Lanrezac at Fifth Army headquarters in Rethel on the river Aisne on the morning of 17 August. The interview was not a success. The two men lacked a common language and suspicion and incomprehension doomed their alliance. Lieutenant Edward Spears wrote of the event:

France

1 – First Army (Dubail)

2 – Second Army (Castelnau)

3 – Third Army (Ruffey)

4 – Fourth Army (de Langle de Cary)

5 – Fifth Army (Lanrezac)

A – BEF (French), from 22 August

Germany

M – Army of the Meuse (von Emmich)

1 – First Army (von Kluck)

2 – von Bülow

3 – von Hausen

4 – Duke of Württemberg

5 – Crown Prince Wilhelm

6 – Crown Prince Rupprecht

7 – von Heeringen

8 – von Deimling’s detatchment

From l’Illustration, Paris, 1915. (HGG)

Sir John, stepping up to a map in the 3ème Bureau, took out his glasses, located a place with his finger, and said to Lanrezac: ‘Mon Géneral, est-ceque –’ His French then gave out, and turning to one of his staff, he asked: ‘How do you say “to cross the river” in French?’ He was told and proceeded: ‘Est-ce que les Allemands vont traverser la Meuse à – à –’ Then he fumbled over the pronunciation of the name ‘Huy’ …. ‘What does he say? What does he say?’ exclaimed Lanrezac. Somebody explained that the Marshal wanted to know whether the Germans were going to cross the river at Huy? Lanrezac shrugged his shoulders impatiently. ‘Tell the Marshal,’ he said curtly, ‘that in my opinion the Germans have merely gone to the Meuse to fish.’

What was even more damaging than this rudeness was that Lanrezac’s appreciation of his own front was not sufficiently detailed, for there were bridges over the Sambre of which his men were not aware. On 21 August the German 2nd Guard Division crossed at Auvelais, between Charleroi and Namur, and part of the 19th Division did the same a little to the west. On that day the bombardment of Namur began. In the next four days all of the forts would fall, putting the hinge of the defence line under German control. In the meantime Lanrezac’s staff persisted in the expression of a determination to move north and the British therefore planned to advance into Belgium. D’Amade moved to take positions centred on Lille, putting eleven battalions in forward positions and twenty-five, supported by six groups of artillery, on the main line of resistance on the river Scarpe, to the British left. On 22 August Lieutenant Spears went to report to Sir John French at Le Cateau. In trying to return to the French Fifth Army forces on the British right, Spears found them falling back and he immediately returned to BEF headquarters with the news. He recalled:

Never have I felt more tired, but the feeling of being well-nigh spent was due far more to the news I bore, and of the responsibility of the report I had to make, than to actual lack of sleep. I felt more and more miserable: if I were mistaken in my deductions or in my observations the result might be terribly serious. Yet the situation, if I understood it rightly, was so perilous that I felt I must convince Sir John of two things; that General Lanrezac was not going to attack whatever happened, and that the position of the Fifth Army was dangerously exposing the British.

The British then decided to stand on the line of the canal at Mons.

II Corps, under General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien, was on the left between Condé and Mons, and on the right, between Mons and the river Sambre at the French border to the south-east, was I Corps under Lieutenant General Sir Douglas Haig. Each had two divisions comprising three brigades of infantry with mounted troops, artillery and engineers. In addition the BEF had the Cavalry Corps under Lieutenant General Edmund Allenby with one cavalry division to the rear of II Corps. In all there were about 72,000 troops with some 300 guns to hold against von Kluck’s First Army’s 135,000 men and 480 guns.

The battle took place on Sunday 23 August and although the Germans were startled by the ferocity and speed of British rifle fire, their advance was relentless. By evening, the BEF was pulling back, having suffered 1,600 casualties. As midnight drew near and the defenders of Mons gained a little rest, Lieutenant Spears arrived at the BEF Headquarters at Le Cateau with the news that Lanrezac had issued orders for his Fifth Army to retreat. D’Amade’s ‘grandads’ had taken the force of von Kluck’s right wing and the poor men of the Territorial Group’s 88th Division were either dead, wounded, taken prisoner or in retreat to the river Escaut. The BEF’s position at Mons had become untenable and confidence in their ally on their right had been severely shaken. Sir John French issued the order to retire at 0100 hours on 24 August, but gave no indication of by what route or to which location Smith-Dorrien and Hague should take their Corps. The Germans were, fortunately, ill-informed about the Allies’ positions and, fearful of an attack on the flank of his Second Army, von Bülow insisted that von Kluck’s First Army should maintain close contact with him instead of swinging west to outflank the BEF. That day Lille was declared an open city and d’Amade pulled back to a line through Douai.

By the time that Sir John’s orders had reached front-line units, daylight had come and, unable to achieve a clean break with the Germans, the British were obliged to conduct a fighting retreat. On the way south-west towards St Quentin, the Forest of Mormal split their route. Smith-Dorrien’s II Corps took the route along the north-western side of the woodland and Haig’s I Corps the road along the south-eastern. The Germans, assuming the British were running as hard as they could, advanced on a broad front but no significant renewal of combat ensued; both sides were exhausted by long marches and heavy fighting. The weather was hot and the ways dusty and filled with refugees. I Corps was also sharing the road with French troops, the left wing of Lanrezac’s army, which compounded the confusion and discomfort. The German advance through and to the east of the Forest of Mormal led to a clash late at night and the precipitate withdrawal of I Corps the next day. II Corps was in serious trouble.

Two Roman roads cross this open terrain. One runs south-west, to the west of the Forest of Mormal, to the canal north of St Quentin at Riqueval – a place the British would next visit in September 1918. The other road, coming south-east from Cambrai, meets its fellow route near Le Cateau. From Cambrai the river Escaut runs northwards into Belgium. Small streams cut north-west across the plain to join the Escaut, among them the Selle, which rises south of Le Cateau and flows through the town. Also through this little town comes the railway from St Quentin, heading off north-east along the river Sambre towards Liège, with a junction taking a line to Cambrai. In the south, near St Quentin, the river Somme rises to snake its way westwards, through open, chalk country. Here there is space to manoeuvre. (See b/w plate 1)

Sir John French ordered Smith-Dorrien to continue the retreat of II Corps the following day, 26 August. The order was received at 2100 hours on Tuesday, 25 August, three hours before the march south to Le Cateau was completed. The ridge at Solesmes, north of Le Cateau which General Allenby had planned to hold with his cavalry to cover further withdrawal, was occupied by the Germans, and, in addition, there was a real threat of a successful outflanking movement on the west. In his defence, Allenby had had the additional problem of the dispersion of his cavalry in a series of running actions throughout Tuesday. Fortunately the 4th Division, under Major-General Sir Thomas Snow, had arrived on Monday, by train, at Le Cateau and other nearby stations, and without Snow what followed would probably have been impossible. Snow and Allenby placed themselves under Smith-Dorrien’s orders. The II Corps commander concluded that there was no alternative but to let the men get as much rest as possible and to stand and fight on the ridge that carried the Le Cateau to Cambrai road. As dawn arrived they hastened to dig what trenches they could. The Royal Field Artillery (RFA), of primitive fire control in these days, was immediately behind them.

On the left, 4th Divison faced north-west in the direction of Cambrai to secure the flank. Along the Roman road, 3rd Division were positioned in the centre and 5th Division and XXVIII Brigade, RFA, were holding the spur overlooking Le Cateau and the Selles Valley where the German 5th Division was already advancing. The progress of the Germans on the right flank during the day, as I Corps withdrew towards St Quentin, eventually forced the artillery to turn at right angles to their original line of fire. By 1400 hours it was clear that Smith-Dorrien’s men could hold no longer and orders were given to retreat. The orders did not reach some units, who fought to a standstill. Three VCs were won in the efforts to pull the guns out. By nightfall the disengagement was complete, and the last troops were making their own way back as best they could. On the left, General Jean Sordet’s Cavalry Corps and d’Amade’s territorials had prevented the German First Army turning the 4th Division’s flank. Indeed, d’Amade had planned to use his reserves, the 61st and 62nd Divisions, to attack the German right, but the ferocity of the German attack on the BEF gave him too little time. II Corps had held that army for a day at the cost of 5,212 killed and wounded, 2,600 taken prisoner and thirty-eight guns. The German First Army did not pursue them as von Kluck was under the impression, as he reported, that he had been fighting the entire BEF – six divisions, a cavalry division and several French Territorial divisions. While the British fell back by way of St Quentin, d’Amade pulled back to Bray-sur-Somme to create a defence along the river from Amiens in the west to Péronne in the east. Von Kluck thought that the entire BEF was facing east and on the march for the Channel, so he sent General Georg von der Marwitz and his cavalry corps on a sweep westwards to cut the British off. The whole situation remained uncertain in what was still a war of movement. Writing in 1918, Marwitz recalled seeing Péronne on his left. As IV Corps was attempting to get there, he took II Corps to Cléry to attempt a crossing of the Somme. He found the marshy valley too wide. Here the ‘grandads’ had succeeded in turning back a German force.

In St Quentin the mood was so depressed that, encouraged by a mayor eager to avoid fighting in his town, two British lieutenant-colonels were ready to surrender their forces to the Germans. Major Tom Bridges of the 4th Dragoon Guards would have none of it however, and swore to evacuate every living British soldier. The exhausted and demoralised troops were hard to rouse to action, but a toy drum and penny whistle bought from a shop still open for business sparked a reaction when Bridges marched his skeleton military band round the square, and by midnight, the last of the BEF had quit the town.

That same day a frosty meeting chaired by the French Commander-in-Chief, General Joseph Joffre, took place in St Quentin from which Sir John French and Lanrezac both departed with their poor opinion of each other confirmed and little else settled, other than the announcement of Joffre’s plan to form a defence line along the Somme and Oise rivers. Simultaneously, significant numbers of troops were being rushed by railway train from the Lorraine front to form a new French Sixth Army in the west which was to be commanded by General Michel-Joseph Maunoury.

As the BEF fell back from St Quentin on 27 August, the Royal Marines were landing at Ostend to take part in the defence of Antwerp. The Royal Naval Air Service Squadron, under Commander Charles Samson, was with them. The marines were recalled four days later, and Samson’s unit was moved to Dunkirk with the intention, in England, of ordering it back home. Before that, however, on 29 August, Samson was asked to use his support vehicles to make a reconnaissance towards Bruges which gave him a taste for undertaking forays into debateable territory that he was able to indulge in the weeks that followed. When they came, instructions to fly back across the Channel were fended off with excuses about adverse weather conditions or any other pretext Samson could offer in order to stay and fight.

To allow the shift of French troops from the east to take place, any further advance by von Bülow and von Kluck had to be held up, so on 27 August Lanrezac was ordered to counter-attack to the west, against von Bülow’s Second Army which was now pushing more south-west than due south. The order was resisted and only executed when, the next day, Joffre repeated it, face to face with his subordinate, and backed it up in writing. Meanwhile the British were retiring swiftly to Noyon from Lanrezac’s left flank. This attack required a massive realignment on the Fifth Army’s front and the danger of exposing a flank to the north. Lanrezac was encouraged to learn that Haig, with I Corps, was ready to act in support and infuriated when French withdrew his subordinate’s offer. On the morning of 29 August, along the river Oise where it runs east to west through Guise, Fifth Army’s X and III Corps faced north and to their left, where the river turns south-west and is joined by the canal from the Sambre, XVIII Corps was ready to attack west. In reserve was I Corps under General Louis Franchet d’Esperey. The German Guard and X Corps were surprised to meet the resistance along the Oise at Guise, but towards the end of the day they had managed a modest advance. To the west the French attack had got nowhere. It appeared that the Germans were on the brink of a breakthrough but then Franchet d’Esperey launched I Corps northwards, rallying X and III Corps in the process, and threw the Germans back. Lieutenant Spears recorded the event:

It was not until 5.30 in the afternoon that everything was ready, and General d’Esperey, riding at the head of the 2nd Brigade, surrounded by his staff on horseback, gave the order for the general attack. It was a magnificent sight. Strange, but very gallant, the bands were playing and the colours were unfurled. The I Corps troops, deployed in long skirmishing lines, doubled forward with magnificent dash on either side of the X Corps. The X Corps and the right of the III were carried forward in the splendid victorious wave, the men frantic with joy at the new and longed for sensation. The Germans were running away, there was no doubt about it.

The British withdrawal from St Quentin was not uneventful. On 28 August there was a gap between I and II Corps into which the Germans were threatening to move. The western arm stopped the Germans near Benay with a combination of cavalry and artillery, but 3 miles (5 kilometres) east, near Möy-de-l’Aisne there was a more dramatic encounter. Where the autoroute now swings down a valley to cross the river and canal, the old road to La Fère crossed the Cerizy to Möy road at La Guingette, to the south of a ridge that marks the edge of a mile-wide valley running east to west. Here, the British prepared to offer battle. The pursuing Germans entered the valley in late morning and attacked the Royal Scots Greys, two machine-gun sections and J Battery, RFA. At Möy were the 12th Lancers, of which two squadrons were sent around to the north to fire on the Germans. J Battery also engaged them. C Squadron, 12th Lancers was led forward, out of sight of their adversaries in dead ground, until close enough to charge. The engagement was settled with steel-tipped bamboo lance and with the sword. The Richthofen Cavalry Corps was comprehensively beaten. That it was a minor action did not prevent the British press portraying it as a major victory, not least because a charge by lancers invoked memories of imagined romance in warfare.

The Times newspaper reported the ‘brilliant action’ and, on the same page, published a message of support and solidarity to the Royal Scots Greys from the Tsar, for the Russian monarch was Colonel-in-Chief of that regiment.

The BEF was by now desperately tired, badly mauled and seriously demoralised. Sir John French sought to pull out of the line to allow his men to rest and recover, but the German advance appeared to be rolling on to Paris and to victory. Joffre was struggling to maintain control. It took the intervention of Lord Kitchener to stiffen Sir John’s resolve to fight on and the replacement of Lanrezac by Franchet d’Esperey to convince French that the BEF was truly part of Joffre’s team. On 2 September he agreed to take up a position south-east of Paris to complete a defensive line with the Sixth Army under General Maunoury north-east of the French capital. The Sixth Army was made up of units of various sizes and differing levels of professionalism. It included the VII Corps, transported from Alsace, two reserve divisions, the 55th and 56th, and was later joined by the 61st and 62nd from d’Amade’s group. To these were added the Moroccan 45th Brigade and, from 7 September, Sordet’s Cavalry Corps, with Bridoux in command. To Maunoury’s right was the BEF, and, running eastwards, the Fifth Army and the new Ninth Army, created on 28 August, under General Ferdinand Foch, and then the Fourth Army under General de Langle de Cary. Joffre had been vigorous in making changes in the French commands, replacing those he decided had under-performed and, as with Foch, promoting those who had impressed with their leadership.

The situation on 5 September. The Sixth Army is forming in front of Paris, the BEF (A) is on the left of the Allied line facing the Marne, while Maubeuge and Antwerp (Anvers) are under siege to the north. From l’Illustration, Paris, 1915. (HGG)

The appearance of massive strength given by the Germans was just that: an appearance. In fact German control of their invading armies was becoming tenuous. Whereas Joffre was rushing about visiting his commanders in person, German Field Marshal Helmuth von Moltke was still far away from his armies, even after moving from Koblenz to Luxembourg on 29 August. A radio signal sent from von Kluck’s HQ at 2100 on 31 August passed through so many relay stations that von Moltke only got it early on 2 September. The orders in response were received by the First Army in Compiègne on 3 September; the orders were to proceed south-eastwards. The Schlieffen requirement to reinforce the right wing was being forgotten amid the multitude of tasks that the German armies had to perform. The sieges of Antwerp and Maubeuge were still in progress, the requirements of the Russian front had drawn away the Namur siege train, supply lines were stretched and Samson’s Royal Naval Air Service aircraft had raided Düsseldorf, though it was not until 8 October that the intended target, Zeppelin Z IX, was hit by Flight Lieutenant Reggie Marix. Adding to these difficulties, von Kluck was now marching south at a pace that was opening a gap between the First and Second Armies. On 30 August von Kluck began a move to the south-east to close up with the Second Army. General von der Marwitz was denied the opportunity to employ his cavalry, as every time he saw an opportunity to release it to outflank the French, the Army Corps insisted he remain on their wing to prevent the French outflanking them.

The change in direction was a welcome relief to the battered divisions of d’Amade’s Territorial Group. The 61st Division had been severely mauled near Péronne and by 28 August had reached Combles, where its commander, General Vervaire, was evacuated, too ill to continue. The 62nd had been harried back by way of Arras to Doullens from where the shattered remnants were able to depart for Paris where they, and the 61st, were to rest before joining the new Sixth Army. Regiments had been reduced to a mere 500 men, cavalry divisions to a couple of squadrons, artillery batteries had run out of ammunition and the infantry’s supplies were almost gone. The ‘grandads’ had paid heavily for their defiance. They blew the bridges over the Somme and fell back towards Neufchâtel-en-Bray, between Amiens and Dieppe. The 81st, 82nd and 84th regrouped there, followed by the shattered 88th. D’Amade reported that he had ‘covered’ Rouen and that, when the men were rested, he would attack the communication lines of the German IV Corps, but the speed of events outran his powers.

In Dunkirk, Commander Samson received a satisfactory message: his squadron was to remain there to carry out reconnaissance duties. On 2 September he was asked to take the British Consul to Lille and they set off, accompanied by a Jesuit priest, Cavrois O’Caffrey, in two cars, one of which was armed with a machine-gun. As they reached the suburbs of Lille at La Carnoy they were stopped and told that the Germans had entered the city. They telephoned the Prefecture to find out if it was true and, on being told the enemy were actually in the building, a series of calls were then made to see if a rescue operation could be undertaken. It was deemed too risky for the civilian population, but in the meantime O’Caffrey had taken the tram to the city centre to find out more. He returned to report the presence of about a thousand German infantry in the main square, so Samson’s little force withdrew.

On 4 September two cars drove to Cassel, a town some 16 miles (25 kilometres) from Dunkirk, perched on a hill rising abruptly from the plain and the scene, in 1793, of the noble Duke of York’s famous march up and down again. News came of the approach of German vehicles from the east, so Samson hurried his little force down to the Armentières road as the enemy came into view. His memoirs record:

As soon as they saw us, the German who was driving the car applied his brakes, skidded half-way round, and started reversing to turn completely. There appeared only one thing to do or they would escape us, and that was to stop and open fire. We couldn’t use the Maxim whilst the car was moving, so I gave the necessary orders and Harper opened fire with commendable promptness.

The machine-gun and rifles were brought into action, putting the Germans to flight. The British waited for two hours in case of a renewed approach, but then a telephone message arrived to say that the German automobile had returned to Lille carrying wounded men. The victorious party withdrew to an enthusiastic welcome in Cassel.

On 5 September General Bidon sent for Samson and asked him to verify the news that the Germans had quit Lille. He set off with four automobiles, three with machine-guns, and a mixed force of French artillerymen and his own RNAS. They moved with care, the vehicles taking turns to go forward, take up a firing position and cover the progress of the others while an aircraft scouted ahead of them. On the way they passed a squadron of cavalry. Arriving once more on the outskirts of the town they found the Germans had indeed departed and so they carried on, to be welcomed by cheering crowds and cries of ‘Vive l’Angleterre!’ Apparently the Battle of Cassel had been interpreted as a sign of the approach of a large British force. In order to ensure the later safety of the town’s administrators should the Germans return, Samson gave them a note saying he had ‘occupied Lille with an armed English and French force’, and signed it ‘C R Samson, Commander RN, Officer-in-Command of English Force at Dunkirk’ which he hoped would give the enemy cause for alarm if they came back. It was still, at this stage, a curious kind of war in Picardy and Artois; almost a nineteenth-century experience.

The situation on 9 September. Maubeuge has fallen, making another railway route available to the Germans. From l’Illustration, Paris, 1915. (HGG)

The German reaction to their experience was different. They had had a much harder time than they anticipated. Hauptmann (Captain) Walter Bloem of the 12th Grenadier Regiment wrote:

At this early period … our ideas of war … were based entirely on the 1870 campaign [the Franco-Prussian War]. A battle would begin at 6 am and end … at 6 pm … early the next morning the pursuit would begin and be continued for two enjoyable weeks with two rest-days in comfortable billets, followed by another good, healthy battle in the grand manner. But this was something entirely different, something utterly unexpected. For a month now we had been in the enemy’s country, and during that time on the march incessantly … without a single rest-day. How many miles had I covered the last few days on foot, being so tired that if I got on my horse I fell asleep at once and would have fallen off? How many anxious discussions had I had with Ahlert regarding the company’s boots? … a few more days on the road and my Grenadiers would be marching barefoot.

On 4 September a fresh instruction was sent, stipulating that the German First Army should face west against an attack from Paris, which was reinforced by sending Lieutenant-Colonel Richard Hentsch, von Moltke’s intelligence chief, on a tour of the army commanders to rebuild some coherence of frontage. The strain was telling on the German commander-in-chief, but the French and British were unaware and struggling to create an effective opposition.

The fight developed into a conflict on a fragmented line, away from the Somme, running east from Paris to Châlons-sur-Marne and on to Verdun. By the late evening of 6 September it was clear that the French Sixth Army was in a perilous position. While it had advanced, it was at great cost and the Germans were hurrying up their reinforcements. The commander of the Paris garrison, General Joseph Gallieni, ordered the 7th Division, newly arrived from the east by rail, to be sent to Maunoury’s aid. When told of the lack of rail capacity to move them, Gallieni ordered the 14th Brigade to be taken by taxi cab. All over the city police stopped cabs, threw out the passengers and sent the vehicles to the Esplanade des Invalides. During the night, taxis, private cars and buses moved five battalions of infantry, some 4,000 men, to the front.

In the centre the German Second and Third armies worked together to put Foch’s Ninth Army under almost intolerable pressure. Reinforced by X Corps from Franchet d’Esperey’s Fifth Army, Foch counter-attacked from an almost untenable position. The Germans, lacking supplies of food, ammunition and fresh troops, had to fall back. That same day, 8 September, the British were shelling retreating Germans crossing the Marne northwards at La Ferté-sous-Jouarre, and the next morning Haig’s I Corps was over the river between that town and Château-Thierry to the east. II Corps fought their way over on Haig’s left and by evening the French were across in Château-Thierry. It was clear to the Germans that they were now in the gravest danger and the decision was made to pull back to the north to establish a new line on the river Aisne. On 14 September von Moltke resigned. He had been unable to turn the hugely ambitious Schlieffen plan into a reality.

Kaiser Wilhelm had, in fact, ordered von Moltke to report sick and in his place appointed the Prussian Minister of War, Erich von Falkenhayn. The situation he inherited was one of increasing stabilisation of the line in eastern France, but with a wide open flank in the west. His long-held opinion that a breakthrough in the east was the solution had become, he realised, no longer appropriate, but with part of his force facing Antwerp and a gap between St Quentin and Belgium, the extent of the terrain outstripped the numbers at his disposal. His eventual decision was to attempt to envelop the French in the west while discouraging them from reinforcing their power there by mounting assaults in the east and on the Aisne. The challenge for both sides was to concentrate sufficient force on this flank, from Paris to Picardy and Belgium.

The key to the problem lay in the unglamorous discipline of logistics. The movement of large bodies of men and munitions depended on the railway system. The German rail connection between east and west ran through Trier, Liège, Brussels and Valenciennes to Cambrai. The line coming south from Belgium to St Quentin passed through Maubeuge, which was held by the French until 7 September, and even then it was of no use until the blown bridge at Namur had been brought back into service. Both routes were in need of repair because the Belgians and the French had destroyed various signalling systems and other minor parts of the infrastructure as they retreated. The French, on the other hand, were in full possession of their Paris-centred rail system, which enabled them to carry troops from the eastern front and transport them west and north to the Somme and towards the Channel coast. On 15 September, Joffre brought General Castelnau from his Second Army in the east to form a new Second Army in the west while von Falkenhayn moved the German Sixth Army under Crown Prince Rupprecht from Lorraine to the St Quentin front on 18 September. But these are the starting dates and the action took time. The German armies were organised into two corps, each of two divisions. The capacity of the railway limited them to moving one corps in four days at the very best. The armies therefore reassembled unit by unit while the situation in the field threatened all the time to outstrip the capabilities of their increasing strength.

The French order for the movement of the XIV Corps of Dubail’s First Army to join Maunoury’s Sixth gives the scale of the challenge. The instruction, No. 650 of 17 September 1914, says that the operation is to commence at 5am on 18 September. The departures were to take place from Bayon (using one platform), Charmes (two platforms) Châtelmouxy (one platform) and Thaon (one platform). In all there were to be up to thirty departures from each platform in twenty-four hours. This would require 109 trains and the diversion of regular traffic to other routes to free up the railway for the XIV Corps. This was a race to build power in the west in order to outflank the enemy rather than a ‘race to the sea’.

The relationship of railway communication to the eventual line of the western front at the end of 1914 shows the pivotal position of Paris and the importance of the Amiens junction to the Allies. The Germans have a line from Saarbrücken in the east via Mézières all the way to Lille in the north fed by lines emerging from Germany. From C.R.M.F. Crutwell, A History of the Great War, OUP, 1934.

While the principal action was taking place on the Aisne, the open country conflict in Picardy continued. On 8 September Commander Samson had been joined in Dunkirk by 250 Royal Marines under Major Armstrong. He was also given the assistance of Captain Richard and the men of the Boulogne Gendarmerie in order to clear the country of bands of German cavalry and cyclist troops roaming from their bases in Arras, Albert and Douai. Attempts to surround the enemy with their automobile-carried force failed; there was simply too much room for manoeuvre. For example, the foray Samson undertook on 12 September took him from Cassel to the suburbs of Lille, down to St Pol and thence towards Arras. Some way short of the town they had a brush with a party of ‘uhlans’ (lancers, but the British tended to use the term for any German horse). No damage was done to either side and the German cavalry rode off. The night was spent at Hesdin. The next day, now with reinforcements – a patrol of eleven vehicles – they drove south-east passing through Doullens. As they left the town on the road for Albert they almost literally ran into a group of six uhlans whom they engaged with rifle fire as they retreated across the fields. Three were killed and one wounded, later dying without recovering consciousness. From his papers they discovered that he had served with the 1st Squadron, 26th Württemberg Dragoons. In his pocket he had a miniature school atlas, in which the map of France was about three inches square, as an aid to navigation.

On 15 September the Second Army’s formation was accompanied by an order to the Territorial Group to force the Germans to cease their activity in ‘the north’ and cover the Allies’ left wing, to police the area already freed of the enemy and to harass the German lines of supply. This tall order required operations to range over territory from the west of Compiégne all the way north to Douai. Two days later d’Amade was replaced, for no apparent reason, by the venerable General Brugère, who was wheeled out of retirement with the order to hold a line between Bapaume and Péronne with the ‘grandads’ of the battered territorial divisions.

Castelnau’s new Second Army began to assemble from 18 September onwards. From the First Army on the Moselle came XIV Corps, by way of Montdidier to Amiens. From the Fifth Army most of Conneau’s Cavalry Corps and the associated 45th Regiment of Infantry moved from the Compiègne area to the Sixth Army’s left wing. The XIII Corps, including the 3rd Moroccan Brigade, and the XIV and XX Army Corps from the east also came under Castelnau’s orders. Meanwhile German army movements were, imperfectly, observed. D’Amade had estimated that the arrivals at Valenciennes reported by French Intelligence, the Deuxième Bureau, amounted to at least an army corps, but there was puzzlement about their destination. Movement from Valenciennes towards St Quentin was at first seen, mistakenly, as a strengthening of the line north of the Aisne.

The movement of Crown Prince Rupprecht’s Sixth Army was planned at a conference with von Falkenhayn in Luxembourg on 18 September. The orders were to destroy the French infantry, thought to be quite few, between Roye and Montdidier using the XXI Corps, and then, with the entire army, to envelop the Allies’ left. Rupprecht and his Chief of Staff General Konrad Kraft von Delmensingen, were not happy with the scheme as, when XXI Corps arrived on 21 September, they would be on their own – the next arrival, XIV Corps, would be two days away. In addition, the rest of the army would continue to trickle westwards, subsequently forcing Rupprecht to feed his troops into action piecemeal. Meanwhile, they decided, Joffre would be speeding his armies to the west with ease, so a simultaneous German attack on the Aisne, or more exactly between Compiègne and Reims, was vital to detain the French in that sector, and a push to create a salient at St Mihiel would concurrently add to French worries in the east.