Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

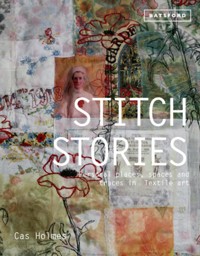

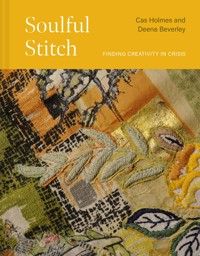

A thoughtful, meditative guide to the ways creative textile art can soothe and comfort us during challenging times. Renowned British textile artists Cas Holmes and Deena Beverley, each well known for their richly textured, deeply evocative work in stitch, collaborate for the first time in this important and timely book. Beautifully illustrated with a wealth of work from both artists along with other embroiderers and textile artists from around the world, Soulful Stitch documents a wide range of stitched responses to crisis, both personal and global. With invaluable advice on how to develop your own work in times of trouble, it explores: • How the restrictions and trials of everyday life can inform your textile work, enabling you to develop imaginative new approaches. • The healing power of stitch to soothe and console, with the simple act of putting needle into fabric providing a mindful route to inner calm. • Practical ways to continue with your textile art practice in the face of seismic life changes, finding creative opportunity in difficult situations. • How to use found objects, repurposed threads and personal items to create deep emotional resonance in your own work. Both authors have recent lived experience of having to navigate new paths through big life challenges, making this book particularly heartfelt. It truly demonstrates how even in the toughest times, creativity in textile art can keep you afloat.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 165

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Soulful Stitch explores and shares the experiences of textile artists working from the deepest parts of themselves, creating work that is meaningful in itself, and healing in the making of it.

Here, textile artists, authors and tutors Cas Holmes and Deena Beverley unflinchingly reveal intimate details of their most heartfelt work, created in extreme personal circumstances which challenged both their creative processes and the two artists as individuals. The process of bringing the book into fruition in such challenging times is also shared, encouraging readers to continue with their own practice even when life throws so many curveballs that creativity seems inaccessible.

Full of practical tips for working in the most difficult of environments, be that living with health issues which compromise energy and mobility, or financial and other pressures, including lack of workspace and time in which to make, these artists have been there, done that and kept on doing it, even, possibly especially, when life had plans for them that didn’t seem promising for their continued creative practice.

As this book evolved, the challenges continued, and the artists developed their individual and collaborative approaches accordingly. They share how they did this in the threads of insight gained throughout the making of exciting new work for this book, and in tips on how readers can reboot their own creativity, no matter what else is going on in their life. This is Soulful Stitch; a journey from the innermost worlds of two artists working in extreme circumstance, with invited contributions from other artists living through every kind of challenge imaginable, while finding solace, connection, strength, resilience and perhaps most of all, pleasure, through the simple joy of stitch. Open a page, breathe deeply, and begin.

Soulful Stitch

‘Derek’s Garden’ (Cas Holmes).

Contents

Foreword

What Soulful Stitch Means to Me

How to Use This Book

CHAPTER 1: In Extremis

CHAPTER 2: Pockets

CHAPTER 3: Messaging

CHAPTER 4: Connections

CHAPTER 5: Nature to Nurture

How Was It for Me?

Further Reading and Resources

Index

Acknowledgements

Credits

Detail of ‘Made in Norfolk (Mustard)’. Collaborative panel by Deena and Cas. Deena’s great grandmother’s Singer sits companionably above Cas’s rendition of her hands at work stitching. The background is of mixed-media vintage textiles and paper. Panel 30 x 90cm (12 x 36in).

Foreword by Deena Beverley

Since childhood, I’ve found enormous comfort in the humblest materials, enjoying the haptic appeal of crumpled old paper, and the narrative in everyday discards. A shopping list found in a supermarket trolley intrigues with its contents and inspires new work. Wabi-sabi for me isn’t a buzzword or trend, but a way of life.

Discards from my own life took on a sudden, enhanced value when my husband and I were evicted at short notice from the extensive studio and workshop complex we had rented, and literally rebuilt from the ground up, over decades. This necessitated a 90 per cent downsize almost overnight, while working full-time and having carer responsibilities. Disability due to chronic health conditions aggravated by stress added to this smorgasbord of stressful events.

As we cleared out the space at speed, it was interesting what we held in high value, saving first. A fragment of cotton parcel string, trodden underfoot, muddied by sodden footprints, I extracted carefully from the tread of my wellies, pocketing it as perceived treasure; I later gilded it with rescued shards of gold leaf that had fallen from a high shelf like angelic confetti onto the dusty barn floor in the forced haste of the move: the prosaic made poetic, tiny glimmers of beauty in the dark maelstrom.

In stark contrast, high monetary value tools and equipment were sold and donated with barely a backward glance. All the while, as leaves whirled around our feet while the winds of change blew, something was shifting, along with the physical stuff and us. The move was seismic in every way, played out as it was alongside other traumatic events in our lives.

I’m a great believer in the old adage ‘diamonds are formed under pressure’, and during this time, Soulful Stitch was conceived. I’d long spoken with Cas about writing a book that reflected those parts of our approach and backgrounds that had informed not just our work, but our whole personal ethos of living authentically – working as if we don’t need the money, dancing as if no one is watching. Mobility issues may have put an end to my dancing days, but making this book together has definitely brought the sparkle back to my worn-out ruby slippers; and I sincerely hope that reading it will bring a little of the soul magic that drives us into your life too.

Detail of ‘Beltane’ (Deena Beverley). Intuitively quilted, appliquéd and embroidered using found fabrics.

Foreword by Cas Holmes

As the use of technology increases, I find myself rebelling against the sense of ‘perfection’ that its use can bring to the ‘creative process’, preferring to seek out the ‘emotionally felt’ and the ‘imperfection’ of the hand-made. I am drawn to the ideas surrounding the Japanese concept of ‘wabi-sabi’, a respect for the maker’s hand, such as the marks that flow from a brush in the making of a scroll, or from the needle when stitching into cloth.

In Deena, I found a mutual respect for the integrity of the making process and a love for creating rich visual narratives extracted from the ephemeral yet familiar materials available to hand. The apparent banality of the found materials I gather is open-ended; these discards constantly inform my work through the prosaic beauty of their ordinariness.

My life partner is a stroke survivor; this has brought considerable change to both our lives and has profoundly influenced how I connect to the simpler things around me as part of my working process. Sharing our experiences of place, of home, and of the past, in the writing of this book has provided intellectual and creative stimulus at a challenging time.

Wabi-sabi has no clearly defined or universally accepted definition in the Japanese language – at best, it can be condensed to ‘wisdom in natural simplicity’. You cannot know what is round the corner, so join us in finding the joy to be found in the ‘imperfections’ of everyday life.

Wabi-sabi

‘Wabi’ is simplicity, impermanence, flaws and imperfection – the kind of perfect beauty found in the marks made by the maker’s hand in writing calligraphy, as opposed to a machine-printed page.

‘Sabi’ refers to the effect that time has on an object and the careful, artful mending of damage; or simple things of daily life that evoke a strong emotional response, such as the transient beauty to be found in spring blossom.

My father’s brushes lie across a sketchbook with work in progress. Marks made on paper or in stitch evidence the signature of the maker. ‘Emakimono’ (book thing) in progress. Japanese boro cloth lies in the background.

What Soulful Stitch Means to Me

What is ‘soulful stitch’? If it feeds your mind and lifts your spirit; distracts you from life’s many challenges; connects you with others, or with parts of yourself you didn’t know, or had forgotten, existed – it’s soulful stitch. It’s salvation in its purest sense. It might not be able to save you from everything life throws your way, but it will comfort, entertain, enrich and enfold you in so many senses that we felt compelled to devote a year of our lives to making this book about it. We live it and we love it. We hope you will too.

Deena Beverley

Stitch has run through my life like the river that flowed behind my grandmother’s home above the butcher’s shop she ran in Norwich. We’d walk along the riverbank and through the grounds of the almost neighbouring asylum (now luxury housing), and listen to the patients singing in the summerhouses, saying hello to those we passed who were well enough to be able to enjoy the beautiful, extensive gardens.

In the other direction was a cemetery, through which we’d walk while reading the gravestones, having passed the coffin maker whose workshop abutted my grandmother’s garden. These walks often ended up in the fantastic classical draper’s shop in Norwich, where my grandmother treated me to skeins of stranded embroidery cotton, along with crisp paper transfers to iron onto whatever old fabric she could spare for my first forays into hand embroidery. Kits followed: apple blossom and briar roses on black grounds – I’m still drawn to these motifs now. When older, I’d be allowed to climb out of the window above the shop front and sit, legs dangling from the windowsill, to draw and paint the flowers on neighbouring window ledges, later to replicate them in stitch.

As the production of this book draws to a close, I write this having returned briefly to Norfolk and find myself re-treading these steps. I realize the experiences that were woven here by my own familial experiences with stitch, and with my grandmother’s normalization of life, death, madness – from asylums to carcasses, and coffins and cemeteries as playgrounds; it became forged indelibly in me, a sense that all of these things are inextricably linked.

This was, and is, to me soulful stitch. In mending and making, we mend ourselves. We make new connections, and strengthen existing ones. Some threads weaken and break, and we deal with that too. The journey begins with a single stitcher, working a single stitch. Make it count. Make it soulful.

Detail of ‘Kantha’ book cover (Opening Doors Within), by Deena Beverley. Found silk and used calico shopping bag scraps.

‘Memories of Gran’ (Sue Stone). I see this portrait every day as I go into my studio. A shadowy image of myself looks on to my Romani grandmother and my father as a baby. In 2016, Sue invited members of the public to take part in her ‘Memories’ project by sharing their memories in the form of images and anecdotes. The resulting work inspired by those collected memories was shown in Sue Stone’s solo exhibition ‘Retellings’ at The Ropewalk, North Lincolnshire in 2019.

Cas Holmes

I do not recall seeing my Romani grandmother or my mother working with any form of craft, let alone needlework, yet I have been told both did so when young, and I have no memories of being taught these skills as a child. My grandmother often spoke to me of her family, and of her mother creating small crocheted items and making lacework to sell door to door in Norwich, or when on the road with her family travelling. I do, however, have strong recollections of my father, a trained sign writer, painting beautifully illustrated shop signs. I picked up a brush long before a needle felt comfortable in my hand.

It was not until I attended art college that I ‘discovered’ stitch; since then, this idea that I can work with a needle as well as paint cloth with colour has remained, entwined with a lifetime’s experience of drawing and looking. The quiet, repetitious acts of stitching enable me to respond to the cloth and the stories it carries.

Detail of ‘Four Corners’ (Deena Beverley). Found fabrics and threads, paper, ink and paint.

How to Use This Book

Deena Beverley

If I’m in the gutter, I will more than likely be there because I’ve seen the glisten of an old bottle-top I’m determined to rescue, or a filthy bit of discarded rag or leaf skeleton has caught my eye. Pretty much all material has value and meaning to me. I inhabit a rich and colourful inner world, the management of which in itself is hugely challenging.

Neurodivergent and chronically insomniac, I barely sleep; my mind racing like a multiplex cinema showing many films simultaneously, without walls between each screening. Bombarded constantly with ideas and concerns, many of these I translate into text and textile art, in part simply to release the sheer weight of information running like computer coding behind my eyes. It’s exhilarating and exhausting in equal measure. Here, I share my thought processes and inspiration with you, so you may develop the relationship between your own inner life and the art you make.

Soulful Stitch has been developed as a pick ‘n’ mix of the inspirations and creative innovations that drive the work of its authors and contributing artists. Dip into any page, and you are bound to find something that speaks to your soul. All you need to do is be as present and attentive to your own voice as you are to that of others. Pause. Tune in to yourself. Listen.

Open a page of your notebook or sketchbook, draw in the sand or doodle on a napkin, or make a note on your phone. Record what speaks to you most insistently from any given page. I guarantee I could open this book at any page at any time in the future and have it spark completely new ideas for work and further research and development. The world is in constant motion, as are we within it.

You are holding the soulful expressions of generations of artists within your hands. Now it’s time for you to add your own voice. I would love to hear your story and see what you make. Welcome to the world of soulful stitch.

‘We are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars.’

OSCAR WILDE

Cas Holmes

I offer the reader a window into my creative practice and the role that found materials and the familiar references of everyday life play in the connections I create between my inner thoughts and the outer world.

The methods I use are accessible and relatively simple; the processing of the techniques covered becomes complex as I evolve the work and develop my ideas. I refer to following ‘a line of inquiry’ as drawing, observation, recording and touch allows me to learn from the experience I have with the materials. Reusing cloth and other found materials is a form of alchemy: transformed anew using colour, layers and stitching, these discards of daily life allow greater freedom to take risks and experiment.

I work as sustainably as I can with the resources I have at my disposal. Many of the tools and materials used in my mixed-media techniques are relatively inexpensive, sourced from items I find at home, in the garden or on a walk; as well as precious items gifted to me or salvaged from charity shops.

My work process falls into three broad areas, which constantly cycle around each other:

Colour – exploring the use of dyes and paints with simple tools;

Layer – different paste and paint approaches to creating collages and three-dimensional pieces using collated found materials;

Stitch – discovering what we can achieve through the interplay between machine and hand embroidery.

The creative process is not easy. We can all feel a little overwhelmed or struggle when embarking on a new course of work. The last few years have been a step into less familiar territory, and I have needed to evolve different ways of working as I carve out time for my own practice. At times, it has been a little terrifying, yet I have come to recognize that this is a totally normal feeling when undertaking something unfamiliar. Doing something that ‘slightly terrifies’ us pushes our learning forward and helps us discover where we want to go. As we become more familiar with the unfamiliar, it becomes less terrifying.

Allow the ideas shared by the authors and artists within this book to act as your guide as you explore and think about the precious pieces you want to use to create meaningful and personal artwork.

Sketchbook showing ‘Cultivate’ (see here) in progress, among materials and objects reflecting my increased respect for and love of the natural world.

CHAPTER 1

In Extremis

Detail of ‘Derek’s Garden’ (Cas Holmes). Text relating to the garden stitched onto fragments of cloth. Poignantly, the first piece of text stitched was Derek asking if I had ‘picked the last beans’. This was a sign he was coming back to me. Hand- and machine-stitch collage worked onto a tablecloth.

In Extremis

Sometimes life doesn’t so much throw a spanner in the works as the whole damned toolbox. Finding enjoyment and creative purpose in life’s toughest times can feel near impossible when surviving the day is a genuine achievement. That’s no exaggeration, for throughout this book we share inspiration from those who’ve walked the walk, even when walking wasn’t possible. Here are tales of hope and inspiration, songs sung from the front line of living in extremis, with art as both comfort and creative outlet.

Deena Beverley

We’ve had to surmount extreme circumstances to produce this book; united in feeling we were, and are, ‘creating in chaos’. The struggle is real!

I’ve interviewed many icons of embroidery who’ve had to adjust to difficult life circumstances. Jane Lemon MBE; the late, great, ecclesiastical embroiderer, was frustrated at the cancer treatment which hampered completion of her epic ‘Prisoners of Conscience’ piece for Amnesty International. Asked how she dealt with the difficulties of working with failing eyesight and other health issues, she responded simply, ‘I just worked bigger’.

The late textile luminary Rozanne Hawksley is another inspirational example. She’d survived so much tragedy it was difficult to render her story palatable to a mainstream embroidery magazine audience. Her work fearlessly confronted and exposed that which we prefer not to acknowledge, and the pain she and her family had suffered had clearly gone into her powerful art.

Conflict, abuse of power, poverty; big life and death issues were her palette. ‘War and Memory’, her 2014 retrospective, took an unflinching approach to what she called war’s ‘terrible glamour’. Loss, love; all human suffering featured delicately, insistently, potently in this tear-jerking monumental exhibition.

In my written and stitched work I have a strong sense of honouring embroiderers who’ve survived and thrived in extremis; who’ve told me their stories; some in person, others through legacy.

You don’t need to be a professional textile artist to make creating in extremis work for you. Make a little. Make lots. Make none at all; enjoy the work of others. All are valid. Sometimes all we can do is survive. As the late Nell Gifford of Gifford’s Circus memorably said, ‘sometimes you just have to go horizontal’. I have a sneaking suspicion though, that when the dust settles, you’ll want to create again. It’s hard-wired into us, and it helps.

‘In the depths of winter, I finally learned that within me there lay an invincible summer.’

ALBERT CAMUS

Cas Holmes

In early September 2021, following a busy day working in the garden, Derek, my partner, had a catastrophic stroke. I watched on mutely while he was bundled into the ambulance, unable to follow due to the COVID restrictions that were still in place.

That any creativity was possible at all during this time is hard to imagine, yet somehow, the following morning, I found a quiet calm in sitting and drawing the pruning tools left on the table from the night before. My hands needed to be busy – no plans, just doing – to calm my worried mind. Gardening, drawing, or stitching began to punctuate my days between the odd hours I could visit the hospital over the months that followed.

At a time when I was getting ready to get back in the world and resume my work as a ‘travelling artist’, my life was put on hold. I continue to struggle to find a way to balance caring responsibilities with my art practice and teaching. Stitch remains at the heart of my work and my need to communicate, as I reconcile myself to a role that has transformed into that of an ‘artist/carer’.