5,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 4,49 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 4,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: WriteLife Publishing

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

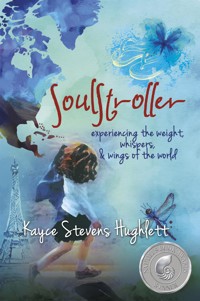

Seductive, sincere, and at times hysterical and heartbreaking, this memoir follows author and good girl, Kayce Stevens Hughlett out of her carefully constructed comfort zone into the world of international travel, healers, wise winged mentors, and inspiring versions of humankind.

SoulStroller introduces a fresh and exciting way of experiencing and living life on one's own terms---expanding readers' world views whether they choose to visit destinations like Paris, Ireland, or Bali, or get to know what home looks like through fresh eyes.

Labeled shy and rendered virtually silent by age six, Kayce had been raised to fit the role of perfect wife, doting mom, and accomplished woman. She fulfilled her mission by her mid-forties when society said she had it all. Society was wrong.

When her eldest child disappears into the haze of addicition, her perfect world changes faster than you can say, Get it right!

Ethereal, gritty, and relatable, SoulStroller is the evolution of a woman too timid to speak her mind into someone who writes her own rules and redefines what it means to live with silence, compassion, and joie de vivre.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

SoulStroller © 2018 Kayce Stevens Hughlett. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, digital, photocopying, or recording, except for the inclusion in a review, without permission in writing from the publisher.

The story is told from the author’s experience and perspective.

Published in the United States by WriteLife Publishing (imprint of Boutique of Quality Books Publishing Company) www.writelife.com

978-1-60808-201-8 (p)

978-1-60808-202-5 (e)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018952765

Book design by Robin Krauss, www.bookformatters.com

Cover design by Marla Thompson, www.edgeofwater.com

First editor: Olivia Swenson

Second editor: Pearlie Tan

Praise for SoulStroller and Kayce Stevens Hughlett

“If you are longing for adventure, Kayce will spark you to book a flight, if you are skeptical of magic, she will turn your heart, and if you are tired of worrying what others think, Kayce will gently take your hand and lead you to a place of peace with yourself and inspire boldness.

“This book is a delight, full of heartfelt stories of courage, love, and loss, brimming with tenderness and vulnerability, dappled with humor, you will keep reading because you want to know how she unfolds and in the process you will experience your own unfolding as well. From bliss to grit and back again, this story feels true because it is so much like true life. And like all good storytelling, it offers you the gift of your life back through a new lens.”

—Christine Valters Paintner, PhD, author of eleven books including The Soul of a Pilgrim: Eight Practices for the Journey Within

“Hughlett finds her voice in the most unexpected places—amidst the grief of life’s challenges, in spaces of letting go, in strengthening through presence.”

—Pixie Lighthorse, author of the bestselling book Prayers of Honoring Voice and the 2018 release of Prayers of Honoring Grief

Other Books by Kayce Stevens Hughlett

Blue, a novel

As I Lay Pondering: daily invitations to live a transformed life

“I see a time of Seven Generations when all the colors of mankind will gather under the Sacred Tree of Life and the whole earth will become One Circle again.”

—Crazy Horse

This journey is dedicated to the generations who have come before me and all those who will follow after.

With hope and gratitude.

Table of Contents

A Note From the Author

PART ONE

Way Back When

1. Life As I Knew It . . . Gone

2. Follow the Rules

3. Beautiful Boy

4. Entering the Desert

5. Voice, Call, & Kittens

6. The Silence of Going Solo

PART TWO

Illumination in the City of Light

7. Paris Perhaps?

8. Bienvenue á Paris

9. Sustenance & Statues

10. Leap Day

11. Meeting Tess

12. Absorbing Paris

13. A Gift Each Day

PART THREE

Pilgrims, Babes, & Threads

14. Irish Whispers

15. The Ancestral Mind

16. Following Threads

17. Darkness of the Night

18. Dancing with the Ancestors

PART FOUR

Wings, Humps, & Hooves

19. Standing on Holy Ground

20. Seriously? Be?

21. Past Horse, Present Bee

22. Egypt Reverberations

PART FIVE

Le Cadeau de Paris (The Gift of Paris)

23. Seasons & Calling

24. Three Aunties & A Rooftop Dancer

25. No Proof Required

26. Oh My God!

27. Jetlag Gyrations

PART SIX

Lucid Meets Liminal

28. This Story Is Not Linear

29. Buongiorno

30. Old Paint

31. Permission & Promise

32. Mirror of the Soul

PART SEVEN

Signs & Souls

33. Why Bali?

34. The Signs Are Everywhere

35. Healing, Balinese-Style

36. Rain Dance

37. Like a Ton of Bricks

38. Generational Healing

39. Lonely Liquid Time

40. Mile High Prayers

PART EIGHT

Fini for Now

41. Following the Story

With Gratitude

Shall We Stroll?

SoulStroller (n.) A person who is present to life in all its intricate details, who listens to the voice of his or her heart and pays attention with all the senses. A SoulStroller sees connections to past and future while living in the abundance of now. She’s willing to take risks and forge her personal pathway, knowing it is inevitable that getting lost and going it alone will be part of the journey. This is how she will be found.

One step, one moment, one heartbeat at a time, a SoulStroller inches, leaps, and soars forward and backward into the fullest version of her true self. Guided by intuition and Spirit, the SoulStroller takes her own hand and strolls through the streets of life—content, curious, compassionate, complete, and filled with gratitude.

A Note from the Author

“Sometimes you must travel far to discover what is near.”

—Uri Shulevitz

When I began writing SoulStroller: experiencing the weight, whispers, & wings of the world, the working title was An Accidental Pilgrim. I thought the overarching story was about my travels—Paris, Egypt, Ireland—and how I’d stumbled into them. Simple enough. I was going to share with readers the places I’d traveled and introduce them to the world through my eyes. Then I began to notice there was no way my inner journey was going to stay out of the narrative.

My story of writing about journeys became its own adventure.

In 2013, dear friend and fellow Paris-iophile Sharon Richards and I christened the concept of SoulStrolling®. Like this book, our SoulStrolling® business wove its way into being through the stories in our individual lives. Sharon visited Paris for the first time when she was fresh out of college. One moonlit evening she stood atop the Eiffel Tower and whispered, “I’ll be back.” She’s been traveling to the City of Light on a regular basis for more than thirty years. I traveled to Paris for the first time in 2008 and the city wove its magic around my heart too. France is now the most oft-stamped destination in my passport. In his book The Art of Pilgrimage, one of our favorite authors, Phil Cousineau, invites readers to “take your soul for a stroll.” This became our mission and SoulStrolling® was born!

When we are intentional about our travel, both the travel and the intentions have a way of changing us.

Through SoulStrolling®, Sharon and I offer adventures for individuals who express a passion to explore extraordinary places, who want to take their personal journeys to new levels, and who seek gentle guidance along the way. SoulStrolling® is a practice of discovering the holiness and wonder in everyday life.

A SoulStroller is a person who chooses to step into the unknown with great intention. To hop on planes to foreign destinations or explore oft-trod neighborhoods with new eyes. To strap on a parachute, take a death-defying leap, and drift into a perfect, soundless stratosphere. To embrace what it means to be inspired, immobile, and immoveable. Action with no visible response. Words without sound. A SoulStroller heeds whispers from the past or present and moves toward the future.

In a very early draft of this book, three of my great aunties hopped into my suitcase and asked to come along for the stroll. My deceased father and young adult son showed up in a recurring dream that I first experienced when I was a girl growing up in Oklahoma. The generations—both living and past—moved seamlessly forward and backward through my thoughts and words as I wrote and slept. They clamored to be heard like sounds on a Sayulita street:

Beep, beep, beep. Back up.

Zoom. Yip. Zoom. Forward ho!

Breathe. Flow. Whisper. Listen.

This is how we heal.

I kept writing page after page, consulting with mentors, attending writing classes and weekly groups. I meditated, prayed, and listened to nature. I scoured my journals and found stories I’d written in the past that spoke to me in the present. It wasn’t until I was deep into the writing that I realized this was a story about voice and healing and so much more than descriptions of the places where I’d walked. It was my personal tale of learning to speak up for myself and finding comfort when I was alone. That and more. This story reaches forward and backward and all around me like the spray of the ocean crashing onto volcanic rocks that hold secrets ancient as the heavens. My hope is that it will reach into your life too.

There is no word, adjective, or sound for what it feels like to have all of this—my travels, my great aunts, the rules I despise, and more—wrapped up inside me, pressing to fly out. Words stick in my throat. I hold the tension of weight and wings, grounded and open, love and fear. A mysterious muse calls me to write about voice then leaves me speechless. I long for my words to flow like a river, to wash over each one of us like holy water in Bali or the baptismal font in Notre Dame, to feel the lift of every wing that has held me throughout this incredible journey. Spirit. Yahweh. Mysterious Unknown.

The theme of wings surfaced in Ireland when feathers lined my pathway. They were there on the Camargue in France when I rose from a stallion’s saddle to become Pegasus lifting toward the moon in a setting raspberry sun. Hot air balloons waved Sharon and me into a tiny hamlet after a long day’s journey, like sphere-shaped feathers dancing in the wind. Pink flamingos sang ça va, ça va on the Mediterranean coast and resplendent peacocks sat with me and read my novel Blue in the Bois du Bologne. Wings on t-shirts. Owls in storefronts. Bees, dragonflies, and crows. Birds whispering from palm fronds and barren oak trees, wrapping their silky feathers around the seasons of my life. White birds in Balinese rice fields and parrots racing across a Sayulita sky. Roosters crowing in the middle of the night. Chachalacas making a racket and butterflies as whispery as eyelash kisses.

Weight, whispers, and wings. The stuff of my life.

I had no wings when I dreamed I rolled down a red rock plateau inside a garbage can. I choked on the feathers that others tried to stuff down my throat. I picked wet plumes out of golden pools of rain and wrapped them with twine to make my own magic wand. I declared with great trepidation that I was a wizard, a white witch, a wondrous being in a human—a very human—body.

There are not enough words to describe where I’ve been or who I’m becoming. I have a hunch the same might be true for you. There is no descriptor for the peace that comes when all the inner and outer chatter ceases and the words and meaning come of their own accord and float to my side.

Author and retreat leader Joan Anderson once said, “There is no arriving, ever. It is all a continual becoming.” No wonder it has taken me decades to arrive. There is no arrival. There is only fluidity of time and a continual blossoming. And still I know that I am here now. I am here now. More whole than when I began this story. Wiser. Stronger.

A bumblebee dives into the orange tendrils by my side, swift and fleeting like the time of which I speak. She whispers, “Be. Simply be. Time is not something to master. It is something to befriend and revere. Befriend the years of your becoming, for they are great and true.”

True. Truth. Trust. I must trust that I am meant to write these stories of wise bees and laughing ancestors. What better person to speak of ethereal beings than a shy accountant from Oklahoma? For if I can believe in the extraordinary, then anything is possible.

SoulStroller has been written in ways similar to how I travel—loose and fluid, like watching the waves roll out and waiting for what the tide brings in. I once warned a cabin mate to be wary of following me home through the woods as I tend to go off the beaten path. I am an explorer. I find tremendous value in getting lost and finding my way again. In fact, I believe that yielding to the act of being lost, whether it be in my hometown or on foreign soil, is a pivotal building block of who I am today.

An urgent desire fuels me to write more about magic and the ineffable. Alongside the desire, fear arises. What if this is all bunk? What if I carry a healing voice within me and no one listens? What if the secrets I hold cannot be adequately named? Is my lifelong loneliness a product of this fear that I will be misunderstood? What if my words hold the key to unlocking individual truths? It’s scary to declare that I hold the secret of bees and butterflies. Do I hold back because I’m afraid to say aloud that I have touched the Great Divine?

How can I speak if I am still the silent one, the lonely girl, the forgotten child who is not important? I linger on my early initiation into loneliness that came one evening in 1962. A tiny princess in a taffeta dress, abandoned in the silence. The weight of alone hanging around my slender neck like a dark talisman. Alone. Always alone. Not important. Always alone. A white butterfly swoops over my head and I swear she is flipping me the finger with her translucent wing. I hear her whisper, “You are not alone. You, my dear, are a wild goddess of the earth. It’s time to share the stories of stones, and wings, and magic with the world!”

The Universe conspires on my behalf to continue to heal my pain and bring song to my voice. I know now that I am never alone as long as there is sky and earth, wind, fire, and water. I must remember to flow like water, to burn brightly as the flame that lights my way, and to ground myself in the earth, to roll around in the red clay of my Oklahoma childhood until the dirt and I become one. Only then can I wash myself clean in the oceanic font that is filled with tears of joy and sorrow. “Alone” is the story I needed to make peace with to grow, to heal, to know that I have everything I need in this life.

I had to be silenced before I could learn the power of my voice.

The act of SoulStrolling® begins when something deep inside—a longing, desire, or dream—whispers Come along and your heart or feet respond Yes! Though sometimes, the greatest journey begins with a definitive Hell no!

Most people think of life-changing moments as the day they fell in love or got married, the birth of a child or death of a parent. But what about those moments that come out of left field and smack you down to the ground, bloody your face, or break a limb? When you pull yourself back up, you aren’t the same person as when you fell. You don’t know how or why or exactly what change the moment has incited, but you know things are different. You are different. You rarely want to relive those moments, because they’re that kind. The hard kind. The painful kind. The oh-God-why-me kind. But you also know that without that moment, you wouldn’t be who you are today.

When my moment arrived, I would have described myself as a brown-eyed Oklahoma good girl who had misplaced her autonomy in daughterhood, wifehood, and motherhood, a dreamer who disregarded her ability to see clearly because she had been looking through everyone else’s lenses, and a free spirit who’d given away her soul to the uncompromising conventions of society. I would have described myself that way, except I was also clueless, voiceless, and wordless.

SoulStroller is filled with yes-and-no moments from my life—delightful, disastrous, delicious—but the crystallization began with one smack-down moment when I knew my life would never be the same. Perhaps you’ve already had your moment. I wouldn’t wish those times on anyone, but I wouldn’t turn away from mine either, because that moment . . . Well, I’m immensely grateful for it. And perhaps, after reading this book, you might be a measure more grateful for your moment too. How wonderful would that be?

Cheers to SoulStrolling® and to your glorious life!

PART ONE

Way Back When

“Beginnings are sudden, but also insidious. They creep up on you sideways, they keep to the shadows, they lurk unrecognized. Then, later, they spring.”

—Margaret Atwood

CHAPTER ONE

Life as I knew it... Gone

“You may not have signed up for a hero’s journey, but the second you fell down, got your butt kicked, suffered a disappointment, screwed up, or felt your heart break, it started.”

—Brené Brown

Labor Day Weekend, 2003

There is an eeriness in the atmosphere and the sky turns a putrid shade of grayish green moments before a tornado hits. On Labor Day weekend in 2003, the signs of impending doom were less obvious than gray-green skies, but they were there. Deep inside my bones, a niggling unease told me our family walked a fine line between tranquil domesticity and despair. I could feel the twister coming but hoped it would lift back into the sky before striking.

“Who wants to go see Finding Nemo?” I asked. It was Saturday morning. Our family of four sat scattered around the kitchen and dining room eating breakfast and catching up on email and current events. It was rare that we were all awake and in one place at the same time.

“Me! Me! Me!” Ten-year-old Janey bounced up and down. “Can I get popcorn?”

“Sure, honey. Movie sounds good to me.” My husband Bill looked up from his Blackberry.

“Do I have to go? Sounds lame,” Jonathon groaned over his Cheerios.

“It’ll be fun,” I urged. “We haven’t done anything together in a long time and summer’s almost over.”

“Yeah. I know. I’d rather go to Bumbershoot with my friends,” Jonathon pressed.

“We already had this discussion,” Bill replied. “No Bumbershoot. You’re too young to go alone.”

“Daaad.” Jonathon made that phlegm-clearing noise, perfected by teenagers everywhere to show disgust as only they can.

I don’t remember the inciting conversation or even if there was one, but on that Saturday evening in early September 2003 after we’d gone as a family to see Finding Nemo at the Bay Theater, Jonathon walked out of the house and didn’t come back. Our beautiful boy with my smile and my father’s lean build disappeared.

The hours that followed Jonathon’s disappearance were a blur. We called every friend we could think of, but he’d jettisoned his old crowd and the new list was elusive. The hours dragged on. We were panicked maniacs, calling anyone we could think of until we finally called 911 and a kind, somewhat patronizing police officer showed up at our front door.

“These things usually resolve themselves quickly,” Officer Bounds assured us. I could feel the subtext: Overreacting parents, here we go.

It was odd to see the police woman sitting at our dining room table, poised with her note pad. She reminded me of a young Sharon Gless from Cagney and Lacey—feminine, all business, and dressed in navy blue chinos and a white button-up shirt. “Any friend’s house he might be at?”

“We’ve tried them all,” Bill answered.

“Okay. What was he wearing when he left?” The questions were incessant, but they felt like our only lifeline to getting Jonathon back. “Eye color? Hair length? Hair color? Height? Weight? Any distinguishing marks?” We answered as best we could.

“All right, Mr. and Mrs. Hughlett. Since he’s only fourteen, we can put out a missing person/runaway report and keep an eye out for him. Please let us know if you hear anything.”

She left her card on the table along with a copy of the incident report.

“Is Jonathon coming back?” Janey peeked around the staircase where she’d been hovering.

“Of course he is, honey,” I assured her with a confidence I didn’t feel.

Officer Bounds walked out the front door and moments later Bill headed out the back to begin a late-night driving vigil. It was futile, but necessary. We had to do something. I stayed home with Janey and tried to get some sleep, but mainly I stared at the coved bedroom ceiling. Bill came home around 2:30 a.m., and the two of us tossed and turned together. Our silence was heavy with thoughts of the direst kind. He’s gone. Dead. In a ditch somewhere. Kidnapped. Stabbed. Shot. Lost. Scared. Alone. There was nothing we could do or say to comfort each other. Exhaustion finally won and we nodded off, only to awaken at daybreak overcome by a sense of guilt that we could sleep while our son was missing.

After a full weekend of hide and seek between Jonathon and us, the pièce de résistance came when Bill called from Harborview Medical Center.

“Um, honey, um . . . I don’t know how to say this . . .” His voice creaked on the line like a garbled recording. “They’ve done a blood draw and an intake screening for drugs.” He paused and I heard him sob. “The nurse says he needs in-patient treatment now.” That sentence stretched out over thirty seconds or more.

I could hear my husband talking through the phone line, but his words weren’t connecting with my brain.

“Wha-what?” I gasped, breath vacating my lungs and threatening to never return. A mass settled inside my throat while I struggled to inhale. Twilight filtered in through the windows of the living room where I stood. Photos of Bill, Jonathon, Janey, and me smiled down from every angle. I pushed the phone away from my ear as if it were a venomous snake. My arms felt like twenty-pound weights were tied to each wrist, and my legs gave way as though someone had kicked me behind the knees. Curry, our golden retriever, circled me on the Oriental rug, panting in confusion.

Our beautiful, boundary-pushing Jonathon was fourteen years old—full of life, full of confusion, and apparently full of drugs.

Time stopped until anger took hold. How could this be? What the fuck? No! No! No! It’s got to be a mistake! I was furious. Terrified. Lost. Searching. Grasping for answers. How did this happen? Why couldn’t I protect him? How could I keep him safe? Nothing had prepared me for this, not even my own experimentation with alcohol and pot that I secretly indulged in as a teenager. The borders of my love and understanding were being stretched to their very limits.

The boundaries that adults set for me when I was a child flared in my mind. Do things right. Follow the rules. Stay inside the lines and everything will turn out fine. I once heard that fine was an acronym for fucked up, insecure, neurotic, and exhausted. F.I.N.E. Well, here we were. Everything was fine.

Somehow, I made it to Harborview on that Labor Day evening to meet with Bill, a doctor, and a social worker. Before the night was over, Jonathon had agreed to enter his first in-patient treatment center.

Tired. Bone tired. Weary. Worried. Then and now. Digging up the bones like a grave digger, resurrecting the story of that summer of 2003. I feel the exhaustion of that time, the exhaustion and worry more than the details. The worry I couldn’t name, was afraid to name, am still wary to name. The underbelly, undercurrent, the river that runs beneath our stories like the one in Hades. I see it. A river of hell. The one with gaping mouths and peeling flesh and floating bones. A life out of control. A child gone. A mother, wife, and woman, alone with her thoughts.

CHAPTER 2

Follow the Rules

“Maybe, in spite of everything and because of everything, you are miraculously, perfectly whole.”

—Bakara Wintner

January 1962

“Mommy, I don’t feel so good.”

“What? No. You’re fine.” My mother reaches her painted fingernails (Avon’s latest winter shade) toward the bottom of my taffeta dress and fluffs the tulle petticoat into a larger circle. “You were flat on one side. That’s better. Now stand up straight.”

I’m in kindergarten and my sister, Dianna, is getting married. It’s the evening of the rehearsal dinner or some equally important affair. Our household is in a flurry and I’ve spent all afternoon having my hair brushed and teased by a woman dressed in a bubblegum-colored smock. Her fingertips are brown with nicotine stains and every time she leans down to whisper in my ear to say how pretty I am, I nearly gag from the smell of stale coffee and cigarettes. Now my hair looks like a tiny helmet formed with Aquanet spray. I’m wearing a black velveteen vest that covers my chest like a soft plate of armor. A tiny girl dressed for show, but the attire doesn’t protect my fragile soul from the acerbic tone flowing from my mother’s lips, which match her nail polish.

“This’ll have to do.” She tries to adjust a stiff curl next to my right cheek. The curl resists.

I squeak out the words one more time. “But I don’t feel good.” “Goodness gracious, Kayce. I don’t have time for this. It’s a big day. You should enjoy it. Now, let’s go.” She tugs at my hand, but I don’t move. “What?” She throws me the look.

I feel my heart withering underneath the velvet bolero and my throat closes up inside my dry mouth. My pink-glossed lips tighten into a grimace and I feel my two front teeth wobble under the pressure. My tiny body wavers and when I think I might fall on the floor, my mother scoops me up and lays me on my sister’s four poster bed. A deep sigh escapes her lips. “We’ll be back later,” she says and turns away, closing the door without a backward glance.

I grew up in Bethany, Oklahoma, a land of red earthen clay trimmed with miles of golden fields and dotted by man-made lakes and oil derricks. Oklahoma is a far cry from the evergreen landscape of Seattle where I now reside. In Oklahoma, blistering humidity leaves a sheen of moisture across your skin through the summer, which begins in April and can carry on until November when storms, brutal with black ice, become sport for those brave enough to dare driving on it. I have a healthy respect for black ice.

Born the second daughter and third child to Daisy Ernestine (an Avon lady) and John David Stevens (a mechanic and truck driver), I was raised to follow rules and be polite while doing so. I was constantly corrected about appropriate use of grammar—always say please and thank you, never say “ain’t.” My crooked posture was a source of constant criticism from my mother and other teachers. I attended etiquette school to become more ladylike and soaked up beauty pageant culture, although I never qualified to compete. I wore corrective shoes, had plastic surgery for a lopsided lip at age thirteen, and frequented beauty parlors from the age of five. But inside my well-groomed exterior beat the heart of a street fighter, a “firecracker” as my son once called me.

As my mind scans through the stories of my early childhood, I can hear my mother speaking as though I were still six years old. “Kayce’s our shy girl. She doesn’t talk much.” I ingested that line like a dark witch’s potion. I tucked the potential firecracker into my back pocket with the fuse on a slow burn. Instead of lighting up my world, I chose to believe that as long as I followed everyone else’s rules and stayed within the lines, life would turn out right, no matter what the situation.

Inside the silence and all of the rules, I learned that asking for what I wanted or being my true self often led to disaster—someone got hurt, disappointed, or felt ashamed. One of my earliest memories is standing in my crib with outstretched arms. I’m about two years old. I can see the anguish on my face and hear my own wailing cry. I need someone to comfort me. Perhaps I’ve had a bad dream or my diaper is full. It doesn’t really matter. In my mind, I see my young mother nursing a black eye and for a moment I wonder if my father was to blame, but in a flash of certainty I know the answer is no. I was the one responsible. I feel it in my bones.

I remember that Mother was on her way to get me that night when she misjudged the angle of the doorway in her grogginess and hit the doorframe with her upper cheek. In the chaos that ensued—mild cursing, tears, an icepack—I was forgotten, left standing alone, and my mother was the injured party.

There was always a downside to being me. I’d be having a glorious time one moment and the next minute criticism or self-doubt would bring the joy-making to a halt. Kindergarten was the one magical place in my childhood memories. Skipping around the block to Mrs. Peck’s school was a grand adventure. I had a sparkling wand of ribbons and stars and loved to wake the other children up after naptime on our floor mats. I felt like a fairy princess.

On my walks to and from Mrs. Peck’s, dandelion wishes called my name and stray kittens became my best friends. If I was feeling especially naughty, I’d scan the block to make sure no one was looking, then scuff my saddle Oxfords on the pavement. The white leather reminded me of the heavy corrective shoes I had to wear at nighttime. Sleeping in the torturous contraption was supposed to correct my toes that turned in at an unacceptable angle. They had a thick metal bar attached to the soles with the toes turned outward. It’s hard to SoulStroll when your feet are tethered together.

A SoulStroller has feet free to wander.

Another story surfaces. I’m six years old and it’s September in Mrs. Collins’s first grade class. I have to pee. I glance at the black-and-white clock over the door and hope it’s close to dismissal time. No such luck. Bulletin boards with neat displays of Dick and Jane readers are arranged around the room, and a row of twelve-inch-high alphabet letters sits beneath the florescent lighting panels. I inch my right hand into the air like a soldier offering a flag of surrender. The teacher doesn’t see me although I swear we make eye contact. I curl inward and feel the underside of my plaid wool skirt stick to the seat and form an itchy nest around my thighs. My Oxford shoes create a muted tap dance on the black-and-white tiled floor as I shimmy side to side, holding my breath and trying to be quiet.

See me. Don’t see me. See me. Don’t see me. My feet wiggle side to side and my left hand slides beneath my skirt, putting pressure on the white cotton panties that cover the v of my crotch. It’s wet, damp. I’m losing the battle to hold the flow back. I hope my classmates don’t notice the sudden whoosh.

For a moment relief fills my sixty-pound body until I look down and see the putrid yellow ring at my feet. I try to make myself as small as possible and concentrate on keeping the crayons within the lines of my coloring sheet. I seek perfection on the page in front of me even though I know the wrong I’ve committed won’t go unnoticed.

After my classmates pour out of the room like bumbling puppies, Mrs. Collins stares at the puddle in disdain, clucks something under her breath, then turns away to call my mother, whose own embarrassment is evident in her face when she comes to get me.

In fourth grade my mother, father, best friend, and I went to a lake resort for a long weekend. My friend and I felt the freedom of running around the complex on our own, giggling as we pushed every elevator button before climbing out and scuttling poolside to sip Coca-Cola. The most present memory of that time, however, was when I later found a photo of my friend and me on the diving board. When my mother saw it, she commented on my chunky thighs and roundish belly, then insinuated how it was too bad I wasn’t more petite like my friend. I was ten years old.

When we were thirteen, that same friend used her small hands to write in my journal about an incident that I was too ashamed to pen for myself. One day a boy from our class stopped by my house after football practice. My parents were out and when he realized this, he said something lame like “I’m tired.” Before I understood what was happening, we were laying on my bed. His attention was sweet and confusing. I’d only kissed one boy before, during a spin-the-bottle game at a sixth-grade party. The boy on my bed kissed me with dry, closed lips and then without prelude, slipped his sweaty hand under my blouse and proceeded to fondle my bra-covered breasts. A dull roar rose in my ears, laced with my mother’s words: Good girls don’t. I’m not sure if she ever finished that sentence, but it spoke volumes on its own. Tears formed in the corners of my eyes, and I lay on my bed like the giant Raggedy Ann doll in the corner of my room and waited for the time to be over. Once again, my words failed me.

Good girls don’t was the mantra of my hometown in the ’60s and ’70s. While women’s liberation was happening around the country, the preachers, teachers, and parents of Bethany, Oklahoma, were making sure that young ladies behaved in a respectable manner. My mother’s sex talk consisted of our hometown mantra, plus her sage advice not to sit on boys’ laps, “because they can’t handle it.” Girls were divided into three classes of sexual prowess: those who did it, those who didn’t, and those who probably did but kept it very well hidden. I fell solidly into the middle group until I was in college, when heavy petting mixed with alcohol and low-grade marijuana tipped me over the edge into a “girl who did it.”

In August 1976, I married the boy who’d been my first sexual partner and who brought me flowers when my father died in a trucking accident eleven months earlier. I was nineteen years old. My sister and mother tried to talk me out of getting married at such a young age, but for once, I swore I knew what was best for me. They didn’t know I’d broken the sacred good-girls-don’t rule, and I was certain that if they did know, they’d agree this was the best course of action.

Dressed in a full-length white gown and veil, preparing to walk down the aisle, my inner voice screamed Run! Instead of listening, I pasted a smile on my face and put one foot in front of the other. Like Scarlett O’Hara in Gone with the Wind, I determined I would figure things out later. Standing at the end of the aisle, I couldn’t even consider disappointing that church full of people. Money had been spent and expectations set, plus my vocal chords were weak. They had no practice speaking true desires.

Around the time of our first anniversary, I decided it was time to break free from the young marriage. We liked each other, but our love was tepid. I went so far as to rent a small room near the university campus where I was working and my husband was finishing school. Then I told my mother about my plans. Even though she’d tried to talk me out of the union, she was adamantly opposed to divorce.

“No one in our family has ever been divorced,” she reminded me. Keeping up appearances was a huge part of our family culture. “The first year is always hard. You’ll get used to it,” she said. So I stayed. When my husband finished college and began working full time, I left my administrative job and went back to school to finish my accounting degree. About a year after I began working in Tulsa, Oklahoma, my husband and I finally agreed that it didn’t make sense to stay together. We amicably divorced six and a half years after we married.

One divorce, a second marriage, and thirteen years after I’d walked down the aisle and heard the prompt to run, Jonathon was born in May 1989. Little did I know my firstborn child would be one of my greatest teachers, and that he would induct me into a world where breaking and creating rules was the norm rather than the exception. Without understanding why or how, he would be instrumental in helping me realize that it was time to live my own life and toss off the chains of perfection and piety I’d been obeying for so many years.

CHAPTER 3

Beautiful Boy

“Perhaps it takes courage to raise children.”

—John Steinbeck

Neither Bill nor I ever claimed to be perfect parents, but we’d always done the best we could, driven by love and a modicum of Christian fear. As adults we can tout our parenting skills, lack thereof, or claim nature versus nurture in measuring our successes and failures, but I believe children come into this world with their own personalities and agendas, ready to conquer their world. Jonathon’s disappearance and subsequent admission to Harborview was not the first time he had done something that was difficult for us to understand. Our 6 lb. 13 oz. baby boy came into this world with the foremost mission to stretch boundaries and challenge us, his parents, to follow him into uncharted territory, whether or not we were ready to go there.

One evening in 1992 when I was six months pregnant with Janey, I was trying to get dinner on the table before Bill got home from work. Jonathon went onto the back porch and pushed the gas grill against the screen door, trapping me inside the house. He looked me in the eye, pulled down his pants, and pooped all over the back porch. He was three years old.

In that moment, my sense of humor was stretched into nonexistence. I hightailed it out the front door, stormed around our corner lot, came in through the back gate, looked at the mess on the porch, and burst into tears. Was God laughing at this childish display or shaking his head in judgment? Was Jonathon relaying a deeper message or merely stretching his independence? The only thing I felt at the time was that I was a failure as a mother. Even the pediatrician shook her head when I relayed the incident to her later. She had no words of compassion or encouragement. I was on my own without a manual to figure out this new chapter of raising and being a human.

Looking back, I realize I wasn’t prepared for this bundle of creativity. I was busy memorizing parenting plans and organizing carpools and fundraisers. Jonathon was a child who needed freedom as much as, if not more so, than he needed a plan. Bursting with innate talent, he created realistic artistic renderings from the time he could hold a pencil, made fabulous costumes out of masking tape and Legos, and spent hours enamored by bumblebees he would capture in a jar, then let go at the end of the day.

In the sixth grade, Jonathon was fed up with the plan we’d created, so he flipped the bird, gave the finger, whatever you want to call it, to his favorite teacher at the small private school that experts had recommended would be a “solid, structured fit” for him. His action caused an uproar, fueled by comments like “behavior unbecoming a good Christian boy.” I was mortified, confused, and exhausted.

Standing in the shower one morning shortly after the incident, I heard an audible whisper: Bring him home. The message both shocked and terrified me, but I also felt a deep sense of peace inside my soul. After much discussion, Bill and I agreed it was the best decision for all, so we pulled our son out of school, and I joined the ranks of homeschooling moms.

Homeschooling Jonathon was a journey in itself. While Bill and I knew it was the right course of action at the time, I was a novice in the world of lesson plans and middle school education. It’s easier to remember what I learned during those eighteen months than what course work Jonathon and I covered. In the writing of this book, however, I remembered how we studied ancient Egypt and the land of the pharaohs where I would travel a few years later. We also studied Michelangelo’s masterpieces and Vincent Van Gogh’s world as an artist that came to life for me when I eventually visited France and Italy. Future SoulStrolling memories were forming while I homeschooled my son.

In addition to lessons on art and history, I affirmed that Jonathon had his own unique way of taking in information that looked nothing like mine or many of his peers. He absorbed stories best by having them read to him rather than reading them himself. Words on the page frustrated him. He preferred drawing to writing, so it became my pleasure to read stories aloud to him while he lay on the sofa with his head in my lap. He taught me that paying attention doesn’t always mean sitting at attention and making eye contact.

Written tests stymied him, but I knew he was learning because he could remember and discuss concepts and topics we’d studied days before with great accuracy. He wasn’t a traditional student, and unlike his mother who had sucked it up and obeyed the rules, he was bursting to break free and making it known. He yearned to be a normal kid, not a sheltered child, and made it his personal mission to attend public school. Bill and I agreed to give it a try if Jonathon finished his curriculum by a set date in the springtime, which he did. For the final quarter of his seventh grade school year, we enrolled him in Seattle Public Schools.

Letting go of the reins was necessary, but looking back, I can’t help but wonder how things might have been different if we’d made another choice. By the time school was out in June, we’d been summoned to the principal’s office more than once, and Jonathon was banned from an end of year school trip “for his personal safety.” According to the principal, he’d made an enemy of another kid and been threatened with bodily harm. The school thought it best if he stayed home that day. The public school experiment had failed. We were at our wits’ end both parenting- and education-wise, so Jonathon spent his eighth grade year at a wilderness program outside of Black Mountain, North Carolina.

After he returned home almost a year later, our roller coaster existence continued. Jonathon stretched the boundaries. We tightened curfews and house rules. He broke them. The cycle spiraled until that weekend in 2003 when his childhood came to an abrupt halt and the world as I knew it shattered. I was left, once again, with the task of making a new plan and trying to figure out how to reassemble the pieces of our broken family.