Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

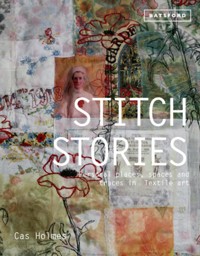

The events of your life, from local walks to exotic trips, can provide endless inspiration for textile art. This inspiring book shows you how to record your experiences, using sketchbooks, journals and photography, to create personal narratives that can form a starting point for more finished stitched-textile pieces. Acclaimed textile artist and teacher Cas Holmes, whose work is often inspired by her life and the journeys she makes, helps you find inspiration through your own life and explains how to record what you see in sketchbooks and journals, which can often become beautiful objects in themselves. She explains how you can use photography, both as documentation and as inspiration, and sometimes incorporate it into the work itself, along with found objects and ephemera. Throughout the book are useful techniques that can be harnessed to add extra interest to your work, such as methods for making layered collages, how to 'sketch' with stitch, and advice on design and colour. If you want to create beautiful, unique work inspired by your life and travels, this is the perfect book for you.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 176

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Cas Holmes, Snowdrop 2014, 27 x 27cm (10½ x 10½in). The image of the snowdrops on the vintage cigarette card is echoed in the free-machine stitch drawing.

Contents

Introduction: finding inspiration for textile art

1. Places, spaces and traces

2. Seizing inspiration

3. The natural world

4. All in the detail

5. Off the beaten path

6. Telling stories in stitch

Glossary

References

Index

Introduction: finding inspiration for textile art

Great Tapestry of Scotland, Designed by Andrew Crummy. Stitch co-ordinator Dorie Wilkie. One of 164 panels totalling 1 x 124m (1 x 155yd). Image based on Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s design for the Glasgow School of Art. Wool embroidered on to linen, 100 x 10cm (39 x 39in).

It is not often that you come across an artist that plays between the worlds of man and nature. Most find inspiration either in one or the other; we are all familiar with textile work that holds urbanity or nature as its core inspiration. However, Cas Holmes has found a third way, the point where both touch, not collide, but touch. This haunted land full of ‘the shadows of marks made by man in the earth’, of ‘reflections in water and flooded fields’, of ‘gardens and seasons changing’, is one that is often missed by the passer-by and artist alike, but it is a rich and rewarding place. It is an inspirational well of harmony and balance, as well as of conflict and division. Something shared and something complementary, as she says herself:

‘We have an intimate relationship with the land, but equally share “common connection”.’

Cas helps others to search and explore the world of the found and the displaced, the cast aside, or perhaps just the mislaid. It is a rich vein of potential and a revelation of connections between … our human world … [and] the world we refer to as natural.

(JOHN HOPPER 2014)

I use textiles and found materials with a connection to the things I find interesting when encountered during my daily activities and places visited as part of my working and social life. My Romany grandmother fostered this interest in the reclaimed – the often overlooked ‘things’ found along the sides of a path, road or field. In Romany culture, these ‘things’ had practical uses: for example willow was made into pegs, and reeds and rushes into baskets. My love of storytelling was inherited from her, and I remember her entertaining me with stories of her childhood travelling.

My father has influenced me too. When I was a schoolgirl, I regularly accompanied him on his walk home from work. He encouraged me to look around and to ask questions about the things we observed on these walks: the plaster decorations above eye level on the medieval buildings in the city streets, the shape of a tree against a winter landscape, or the simple breaking through of the first snowdrops or bluebells in our local wood.

I like to ‘do different’, as we say in Norfolk, and find different ways of exploring my ideas. I am still interested in the commonplace, things observed on the edges of our vision, and my connection to cloth as an artist and teacher has enriched my investigations. I spent four years at art college, training in painting and drawing, but soon became involved with the world of stitch. Paradoxically, my own works have since been described as ‘painting with cloth’. I work without defined boundaries, cutting, tearing, painting and sewing cloth as I trace a personal response to the historical, environmental and social heritage of a place and create new meanings within my work.

A social fabric

The Butler-Bowden Cope c.1330, Victoria and Albert Museum.

Textiles are the social fabric of our cultural history. Everyday stitched textiles for domestic use, where they have survived, remind us of our family connections. Some of us still use items that have been handed down. Historical pieces housed in museums and National Trust collections, from the richly embroidered gowns of the wealthy to the textile hangings for walls and beds, reflect our shared history and remind us of the significance and value of textiles as a symbol of status, comfort and wealth.

The idea that cloth and stitch can be used to communicate a story is not new. Surviving examples of Opus Anglicanum (English work) embroidery, which were mostly designed for liturgical use in the form of copes and vestments, described narratives from the Bible in visual form. These exquisite and expensive pieces of medieval embroidery, of which few survive, contained complex decorative motifs such as flowers, animals, birds, beasts and angels, as well as figures of the saints and biblical characters, all heavily embroidered in gold and silver thread and rich silks. Such was the importance of this art form in medieval England that BBC4 dedicated an hour of prime-time television to a discussion on Opus Anglicanum. In his introduction the programme, presenter Dan Jones (2013) described the quality of stitch in the Butler-Bowden Cope housed in the collection at the Victoria and Albert Museum: ‘It is almost as if this whole piece has been signed with a needle “This is from England” ’, and further comments: ‘The English elevated the craft of embroidery into an art of stunning realism and emotion.’

The use of stitch remains at the centre of our lives today. At the same time as the referendum was being held over the question of Scottish independence in 2014, the Great Tapestry of Scotland was being exhibited in the Scottish Parliament buildings. The brainchild of the author Alexander McCall Smith and historian Alistair Moffat, the tapestry was designed by Andrew Crummy and work on its illustrated panels was carried out by over 1,000 volunteer embroiderers in one of Scotland’s largest community projects. It follows in a grand tradition of stitching narratives: the Bayeux Tapestry, depicting the conquest of England by William Duke of Normandy in 1066 at the Battle of Hastings, is the most well known of the genre.

Artists continue to use cloth for reasons beyond its practical qualities. It ties us to the past and reflects upon the present. Sue Prichard, curator of textiles at the Victoria and Albert Museum, talks about this intimacy and the intriguing relationship she has had with cloth since childhood, when her grandmother taught her to knit and sew:

Domestic textiles are very important to me. My first sewing box was made of cheap, brightly coloured cardboard but I loved that box with a passion and it was the first thing I turned to when I arrived home from school. I made table mats, chair-back covers, needle cases, pincushions – all from scraps and mostly from my grandmother’s fabric stash. I would gift these items to various members of my family, but nobody appreciated them as much as my grandmother. She worked as a domestic cleaner in a large house in Chelsea as well as running her own home, but always took pleasure in sitting down at the end of the day with her needle. My life differs from my grandmother’s on so many levels; however, I always find time to connect to my past. Now I have many sewing boxes in the sitting room, bedroom and kitchen – all filled with my grandmother’s needles, pincushions, scissors and hundreds of buttons, all recycled and kept for a rainy day.

(SUE PRICHARD IN A LETTER TO CAS HOLMES, JULY 2014)

She further explains how the V&A has had a lasting influence on her work:

The V&A has always been my local museum. My grandmother brought me here when I was a child and I remember wanting to walk through the doors marked ‘Staff Only’. I was intrigued by what lay behind. That thought’s still important and informs my work.

(SUE PRICHARD IN AN ARTICLE ‘DOMESTIC GODDESS’, EMBROIDERY MAGAZINE, MAY/JUNE 2014)

As we handle cloth and learn from others, we equally become aware of the story woven into its making.

In this book

Detail of a winter tree in a paper collage with ink colours and drawing on top.

This book builds on the design ideas and creative processes briefly discussed in the chapter ‘Magpie of the Mind’ in my book The Found Object in Textile Art, and takes a closer look at how the everyday and the familiar can be a starting point for developing ideas. We look at connections to places and subjects of interest as a means of developing stories or narratives in stitch and cloth. There are ideas for practical projects linking techniques to concept, supported by examples of work from some of the leading practitioners and artists in textiles.

In chapter 1, ‘Places, Spaces and Traces’, we consider approaches to keeping a journal or a sketchbook and other methods for recording ideas. Collected materials are a starting point for development, and we can explore the qualities inherent in them. There are practical exercises to help you translate ideas into cloth, mixed media and stitch.

For suggestions on how to come up with ideas, look at chapter 2, ‘Seizing Inspiration’, which explores traditional and unusual sources. Chapter 3, ‘The Natural World’, shows that the world we live in can be a rich resource for our creativity, from the detritus of urban backyards and gardens to seasonal changes in the landscape.

‘All in the Detail’, chapter 4, looks at how works can be imbued with a wealth of rich detail in order to be read on a number of levels, and also covers printing techniques and making book forms. Chapter 5, ‘Off the Beaten Path’, looks at responses to personal themes and interests, the history and properties of cloth and stitch as a resource, and artists’ interactions and comments on historical and social narratives. Chapter 6 continues this theme but focuses on the possibilities of hand stitching, in ‘Telling Stories in Stitch’.

Interwoven into the chapters are a variety of processes and techniques that you can adapt to your own creative approaches so you too can ‘do different’.

PLACES, SPACES AND TRACES

At some point, all artists need to find their own approach to their subject matter, enabling them to make work that is meaningful to them and produces an individual take on the world. The motivation behind our desire to make things is as relevant as the way we make them. For me, journeys strike a particular chord. Travel takes place in the mind as much as across land or even continents. The anticipation of a journey not only prepares me for what is to come but is also sweet with expectation about what I might do on arrival. I use the time spent travelling to think, and to make connections between my home territory and the destination. I collect materials, take photographs, and make notes and sketches to record what I see. Your artistic take on the world could be sparked by your daily journey to work, seasonal changes in your garden, family stories, local history, or even an intuitive response to the feel and history of a piece of cloth. Such things provide a rich resource in developing your own narratives, or what some may call a personal vision.

Stitch-sketching

When the woman you live with is an artist, every day is a surprise. Clare has turned the second bedroom into a wonder cabinet, full of small sculptures and drawings pinned up on every inch of wall space. There are coils of wire and rolls of paper tucked into shelves and drawers. The next day I come home to find that Clare has created a flock of paper and wire birds, which are hanging from the ceiling in the living room. A week later our bedroom windows are full of abstract blue translucent shapes that the sun throws across the room onto the walls, making a sky for the bird shapes Clare has painted there. It’s beautiful.

AUDREY NIFFENEGGER, THE TIME TRAVELER’S WIFE

Portable sewing kit against the background of a work in progress. I carry this along with a travelling sketchbook and drawing kit kept in a small clutch bag.

Developing a vision

The activity of drawing and recording my daily observations, and the realization of some of those ideas in textiles, is a process I call ‘stitch-sketching’. I have spent considerable time thinking through ideas and developing the processes behind them, both as an artist and as a teacher.

The act of drawing informs rather than ‘directs’ my ideas in cloth and is an important part of my reflective practice. The mechanics of making a mark differ as well. A drawn line is ‘surface bound’ – it is largely worked on to (and bites into) the surface of the paper or canvas ground and usually lacks any relief. Work in stitch requires it to be worked through the front and the back of the material, giving a texture to the cloth or paper. This direct interaction of thread, needle and material creates its own vocabulary of marks, which is unique to the feel and the look of the work.

On the relationship between drawing and stitch, Nigel Hurlstone (2010) refers to ‘the potential of [machine] embroidery to create a new and different language that does not duplicate the original source, but breathes into it a different life that celebrates the haptic qualities of stitch and the unpredictability of cloth and thread as a way to leave an imprint of thought, time, process and the hand of the maker on and within a surface.’

The refining of processes and approach requires practice, through which you can learn to develop your ideas and portray them in a way that is unique to you. Looking around you, making notes, taking photographs and drawing in a sketchbook are great ways of developing your vision, but you also need to master textile skills and develop stitch techniques to bring your ideas to fruition. Learn all the techniques that interest you, but don’t be afraid to experiment, adapt processes and make mistakes – failed experiments are time well spent. Work without fear and push yourself creatively so that you can spot opportunities where you would not normally expect to find them.

Equipment and materials

Over many years of travel and being on the road (without a car), I have learned to carry the bare minimum. If I forget something, I make do or improvise. I will exchange and dispose of resources – such as found objects, fragments of cloth and paper – as they catch my eye. Limiting what you use to what can easily be carried is a useful creative tool. Materials and tools are as individual as the artist who compiles them, and often reflect the character and nature of his/her work. I carry the following items in a small, portable kit whenever I am away for more than a day or two:

• Small sketchbook or journal – and on the rare occasions that I don’t have one with me, I improvise with found paper collected en route, which you can do too.

• Selection of pens, wax crayons, pencils, water-based paint, small brushes, glue stick, rubber bands (to hold pages down) and a medicine bottle to use as a water pot.

• A viewfinder (an old picture-frame window mount, slide mount, or envelope windows can make good alternatives).

• Scissors, scalpel, 15cm (6in.) steel ruler.

• Stitching kit kept in a small textile pouch: needles, small selection of threads and scissors.

• A point-and-shoot camera.

• Tablet or phone for reviewing work.

I carried the above kit around Australia and the USA and it was sufficient for most of my teaching projects.

A journal: recording process

Ann Somerset Miles, Mapping Seed Packet Treasures, 2013. This project began as part of Ann’s gardening blog: ‘The thought of the wonderful plants you can grow from tiny seeds inspired what was going to be a simple zigzag booklet. But once started, the creative aspect took over and it has become double-sided – 12 seed-packet panels on one side, and 12 map panels on the other side.’

It is a richly rewarding experience to develop a sketchbook or journal and you can work in it in a number of ways. You may require solitude, time and quiet as your work evolves, or prefer to work with others in a small group as part of an experimental approach. Journals can be undertaken to record travel, new experiences, or to research a design aspect for a new project.

The sharing of studies digitally, through forums and blogs, can be a useful way of discussing ideas and getting feedback on your work. There are many online certificated courses in textiles, as well as informal workshop blogs which allow for the exchange of practical skills needed for developing sketchbooks and creative textile ideas.

A diverse range of media, materials and methods can be used to record your ideas. Drawing, print, diagrams, photographs, images, text, journals, indexes, dictionaries, mind mapping and many other approaches form part of the artist’s tools for exploring and communicating complex visual ideas. Keeping a record, creating a journal or recording in a sketchbook as part of a reflective process is a valuable part of your creativity.

An artist’s journal

Ann Somerset Miles works from her studio in the roof space of her Cotswold farmhouse and, when travelling, on a tiny table in her caravan. She is also a prodigious journalist:

I manage to get to my worktable on most days and am continually experimenting with techniques new to me, or creating samples for one of the numerous fabric/paper journals that are always in the pipeline. Samples are filed in stackable boxes or loose-leaf folders alongside copies of notes from my sketchbooks. I love to say ‘What if?’ and not be afraid of failure – though even the rejects are repurposed.

Jane LaFazio

Jane LaFazio is a mixed-media artist and teacher working in paper and cloth. She lives in San Diego, California, USA. She discovered her ability to draw when her beloved husband had a serious illness, requiring her to become a full-time carer for a while, explaining:

I was losing the ‘Jane’ in me, while grieving my husband’s cognitive losses from his acquired brain injury and the future plans we’d made. I signed up for a drawing class, every Tuesday morning. I realized I could draw!

As Jane’s work evolved, she embraced the Internet and social-media platforms, recognizing the role they could play in the sharing and exchanging of ideas. She blogs frequently about her creative pursuits, sharing tutorials and pages from her sketchbook, or reflecting on recent trips that have provided her with inspiration.

Her subject matter is the things she observes regularly, including the eucalyptus trees prevalent in the local area, as she reveals:

There are many types of eucalyptus trees, some with long, thin leaves with shades of blue, green, red and purple. Other varieties sprout lovely pods, and soon those pods open to brilliant pink silky floss. As I walk in my neighbourhood, I often bring home a leaf, blossom or pod to draw in my sketchbook.

I do what I describe as ‘designs from life’, where I will draw and paint the subject as realistically as I can in the time I have. Then, inspired by the shapes I’ve just drawn, I let my imagination take over and reference my drawings to make simple graphic designs to use in the creation of a hand-carved stamp, a rubbing, a stencil or a silkscreen.

Drawings of the blooms in progress.

Jane LaFazio, Eucalyptus Blooms, 2013. Free-motion drawing with sewing machine on to fabric printed with thermofax screens and stencils of the blossom. A three-dimensional element was added with blossom worked with Lutradur and ‘strings’ of fabric machine-zigzag stitched into cords.

A sketch in time

When I pull out a sketchbook or journal and look back at my studies, I am taken to a specific place and time. The studies reflect the points at which I have stopped and looked, particularly when travelling. The drawings and accompanying notes give a better recollection of that experience, or place, than any photograph. Equally, changes in time and weather, shifting light, and a sense of place become embedded in the journal as part of the process of recording. I glue various small items collected from the locality into the pages, make rubbings and prints from leaves and seasonal plants, and record the shifting light and patterns seen in the landscape in the colours and textures used in the drawings.

Hunting and gathering

Log your progress in whatever ways feel suitable: in a notebook, a sketchbook, on a wall in your studio, on digital media or by using a combination of all these. I still like to carry a small sketchbook and pen whenever I can, but will often take a quick snap with my phone, or make notes on my tablet of things of interest. I often refer to this part of my process as ‘hunting and gathering’, and carry a small bag to collect items to use.