14,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Liberties Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

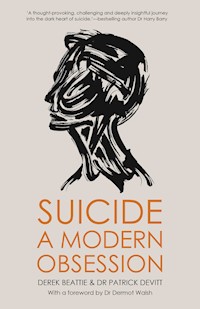

When is it okay for a person to kill themself? How have ideas about this changed over time, and how do they differ across cultures? How do Ireland's suicide rates, especially among its young men, compare to rates in other countries in Europe and beyond? Are we obsessed today with the idea of suicide? Is it possible to prevent suicide - and, if so, how? Should we try to prevent all suicides, or are there some that we should allow, regulate, even assist? Might some suicides be rational? How are families affected by suicide? What can they do if a family member is suicidal? How can they cope after a suicide? Are doctors able to identify which pregnant women are at high risk of killing themselves? Would allowing these women to have abortions make them less likely to kill themselves? In this wide-ranging review and analysis of historical and scientific research on the topic of suicide, authors Derek Beattie and Dr Patrick Devitt take an unflinching and often chillingly rational look at these questions and many others.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Suicide

A Modern Obsession

Derek Beattie and Dr Patrick Devitt

This book is dedicated to all those who have died by suicide and to their families

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the patience and assistance of our friends and families. Thanks to those who gave up their time for interviews: Professor Ella Arensman, Dr Justin Brophy, Rene Duignan, Joan Freeman, Dr Declan Murray and Dr Dermot Walsh. Carl O’Brien of the Irish Times was especially helpful and we are grateful to those families who opened up their grief to Carl in such a public way. Sean O’Keeffe of Liberties Press has remained enthusiastic since we first approached him with our idea for this book, and he has been a constant encouragement. The professionalism and guidance of our editor, Sam Tranum, and all the staff at Liberties have been invaluable. This work has also benefitted from the advice of Dr Selena Pillay, Stephen Shannon and a number of other colleagues.

Foreword

By Dr Dermot Walsh

I am delighted to provide a foreword to this contribution to an issue that has become increasingly the subject of debate and media attention in Ireland in recent years. Such consideration, not all of it well informed, is understandable, as suicide is a major cause of mortality, particularly among young males, and therefore constitutes a significant public health problem. This book brings examination and critical appraisal to bear on the issue of suicide internationally and within Ireland. It includes an historical review of the matter, from antiquity onwards, looking at how the taking of one’s life was perceived in widely different cultural settings. It also reviews causes and examines preventive endeavours. It does not neglect the distress of those – family and others – affected by each suicide and the provisions necessary to ease their pain. And it includes some evocative case histories.

Within the narrower domestic focus of Ireland, issues relating to suicide, its public perception, and indigenous preventive strategies are examined. In this context, the main interest from an Irish point of view is the original, perhaps controversial focus it brings to bear on the effort expended on prevention, grappling with the issue in the recent Irish context.

During the nineteenth century, the number of recorded Irish suicides was extremely low in the European context and, despite a moderate official increase before the First World War, it fell away again in the post-war decades. It took some time to establish, on a scientific basis, an approximately accurate rate, as distinct from the official rate as returned by the reports of the Registrar General compiled from coroner’s determinations as submitted to the Central Statistics Office (CSO). Critical examinations of coroner’s and hospital records of violent deaths revealed that the ‘true’ rate of suicidal death was at least twice as high as represented in CSO data. Nonetheless, there were reasons for believing that, even allowing for a revised death rate more accurately representing the real situation, Irish suicide rates were still relatively low in the international context.

Then, in the third and fourth quarters of the twentieth century, suicide numbers and rates in Ireland began to rise – according to both official and unofficial numbers – although the gap between these two assessments had by then closed considerably. By late-century, however, while Ireland’s overall suicide rate was still in the middle of the European range, the rate for its young males had increased worryingly and was greater than the rates for young males in most other jurisdictions. These suicides were quite often impulsive and carried out in the context of alcohol, by young males not generally perceived as suffering from mental illness in the formal sense, despite the claims by researchers that most suicides occur in persons with established mental disorders. This increase then flattened out in the early years of the twenty-first century. While long-term trends were clear, year-on-year and regional variations within Ireland were also less meaningful because of the small numbers involved.

Youth suicide in Ireland became an issue catalysing considerable popular and political preoccupation with prevention. Organisations active in prevention, small and large, flourished and prospered and competed for considerable resources to pursue their activities. From the 1990s to early 2000s national policy documents were produced advocating numerous intervention typologies. And, more recently, the Health Service Executive (HSE) has identified suicide prevention as one of its major service programmes in mental health. Simultaneously, data has been gathered on persons presenting to emergency departments of general hospitals describing the occurrence of self-harm, and the characteristics of such persons, most of whom, in fulfilment of HSE policy, are evaluated by dedicated nursing staff.

This book points out that much of this activity, some of it resting on inspirational rather than scientific insights, and little of it evaluated in any critical manner, may be of doubtful benefit. Suicide prevention, whether on a population or high-risk basis, is challenging – as this book points out. Searching for causal relationships in short-run and unstable data can thwart many a research endeavour, given the rarity of suicide and the wide prevalence of perceived risk indicators. But this publication reaches beyond the domestic scene and examines the relationships between international impacts such as economic recessions, and cultural influences.

A nation has the responsibility to preserve human life, including by preventing suicide. This book highlights the difficulty of this moral and political obligation, given the heterogeneity and complexity of the roots of the tragedy that is suicide.

1.

Introduction

In July 2012, Ireland’s then minister for health, Dr James Reilly, described suicide as ‘a tragedy that we are constantly working to prevent’. Kathleen Lynch TD, minister of state with responsibility for mental health, reaffirmed the government’s commitment to preventing suicide in September 2014 when she stressed that all of the cabinet was very concerned about the high rate of suicide in Ireland. Yet some suicide-prevention campaigners claim that the government is not doing enough to tackle the problem.

It is difficult to level the same charge at civil society and ordinary Irish people. In a country with a population of just over 4.5 million, there are around 400 organisations dedicated to preventing suicide. Typically, these organisations have developed as well-meaning local responses to the tragedy of suicide.

The Irish media are fascinated with the high incidence of suicide among young males in the country and eager to offer suggestions on how this problem should best be addressed. In a 2014 article coinciding with World Suicide-Prevention Day, Arlene Harris of the Irish Times suggested that:

Society has realised that, in order to reach out and help people who are struggling on the brink, the topic needs to be discussed openly, and those who are suffering need to know there is no shame in feeling despair.1

Interest in suicide crosses many cultures. A Japanese book, the Complete Manual of Suicide, contains detailed descriptions and analyses of different suicide methods and has sold more than a million copies. The South Korean government is so concerned about the prevalence of Internet content promoting and encouraging suicide that a hundred people are employed there to monitor the Internet for such material. Google generated around 19 million results using the word ‘suicide’ in November 2014.

So suicide is clearly a topic of enormous public concern and interest. The question is why. Though it may be difficult for those who have lost a friend or relative to suicide to comprehend, it still remains a relatively rare event. In most developed countries, the number of suicide deaths is just about comparable to the number of road-traffic fatalities. While there is significant interest in reducing mortality from road-traffic accidents, the public are not as feverishly gripped by the topic. Why is there apparently more interest in suicide than in road-traffic accidents?

The roots of what we describe as the ‘modern obsession’2 with suicide can be traced back to the nineteenth century. Suicide started to captivate the public imagination when rates increased in many Western countries in the second half of the nineteenth century, and mortality from many of the other main causes of death decreased.3 Less-hostile societal attitudes to suicide were also a legacy of the Enlightenment and further fed the development of this fascination. The Christian prohibition on voluntary death, as well as the harsh treatments of the bodies of suicide victims, had ensured that for centuries before this, there had been a huge social taboo around the topic.

Our preoccupation with suicide does not mean that the stigma surrounding the issue has entirely disappeared in the twenty-first century. Introduce suicide into a conversation at any social occasion and a wide range of reactions can be expected, from silence to sadness, from a defence of the right to suicide to outrage that more is not being done to curb the problem. The well-known anti-psychiatrist Thomas Szasz bemoaned the fact that English has only one word to describe self-inflicted death, one we hate to utter.4 It is not uncommon for families who have lost relatives to suicide to encounter negative reactions. People may avoid speaking to them, or change the subject when a bereaved family member wants to speak about the deceased.

The continued existence of a stigma does not hinder – and, in fact, may explain – some of the intense interest in suicide, much as banning a film can entice more people to see it. There is certainly sustained media interest in voluntary death, often reflecting what consultant psychiatrist Dr Justin Brophy, the chairman of the Irish Association of Suicidology, has described as ‘a peddling of tabloid interest in human misery and despair’.5 Media guidelines that emphasise the need for sensitivity when reporting on such situations are regularly ignored. For example, the reporting on the March 2014 suicide of fashion designer L’Wren Scott saw a number of British tabloids fascinated with capturing photographs of her grieving partner, Rolling Stones singer Mick Jagger, reach new lows.

Though suicide is relatively rare, there are still around 800,000 suicides around the world every year. Millions are left behind to wonder why these were not prevented. Often, they grapple with understanding why their loved ones killed themselves, and with their perceived roles in the deaths, wondering why they did not pick up on the signs. The effects of suicide are far-reaching and extend to friends, peers and work colleagues. Health professionals and those working in crisis services can also be deeply traumatised. Some start to question their own competence or resolve to completely avoid treating suicidal clients in the future. This burden can be aggravated by grieving families, who may actively blame professionals for not averting the death. After a patient’s suicide, there will usually be detailed reviews of their care. Such appropriate and important avenues for learning sadly often foster a culture of blame. No wonder, then, that mental-health services are obsessed with suicide, attempting to predict and prevent it, usually through psychiatric intervention.

*

The nineteenth-century French sociologist Emile Durkheim defined suicide as ‘all cases of death resulting directly or indirectly from a positive or negative act of the victim himself, which he knows will produce this result.’6 Albert Camus, the twentieth-century existentialist philosopher, believed it was the only really serious philosophical problem. According to existentialism, we determine the definitions and directions of our own lives bearing in mind that our lives are trivial in the greater scheme of things. In this context, Camus apparently once posed the question, ‘Should I kill myself or have a cup of coffee?’7 Jennifer Hames and others, in a 2012 academic journal article, wrote about what they called the ‘high-place phenomenon’, a sudden urge to jump from a high place, experienced by both those with suicidal thoughts and those who have none – they could, in one simple act, eliminate a life, with all its so-called meaning, complexity and importance. 8

Suicide can be viewed from a multitude of other perspectives, in addition to the sociological and philosophical. These include religious, psychological, political, cultural, public health and even biochemical perspectives. Suicide goes back to the origins of civilisation; it seems always to have existed. A rich history of suicide among the ancient Greeks and Romans can be unearthed, which mainly focuses on the deaths of aristocratic men.

The father of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud, believed suicide was the result of a murder instinct turned inwards, but the view of mental-health professionals that it is predominantly caused by mental illness has been a much more enduring theoretical view. Statistical peaks can be found in unmarried men and in older men. In some countries, there is a high prevalence of suicide among young men. In Ireland, it is the leading cause of death among males between the ages of fifteen and twenty-four.

Some historical suicides were regarded as noble, honourable and brave – especially when conducted in the context of battle. The ‘honourable death’ remains a source of great pride in some Eastern countries, especially Japan. In other parts of the world, however, suicides are almost always seen as tragedies. The loss of a young person in their prime is regarded as a terrible waste and is a huge emotional blow to their friends and family – and especially to their parents, who reared them and cannot have expected that they would be predeceased by their offspring.

It is not surprising that great effort is expended in attempting to understand the motivations of those who take their own lives. Through greater understanding, it is hoped that we can ultimately identify the means of prevention. The isolation of specific causes for a particular suicide is a very difficult task because, frequently, many factors are involved in the decision.

There are a number of factors known to be associated with suicide. Cultural factors are relevant and account for the variation in rates between different countries and within countries. A high rate of alcohol and substance abuse and dependence is also associated with suicide. Individuals suffering with serious mental illness are more likely to kill themselves. Certain professions are known to have a higher prevalence of suicide – for example, doctors, dentists, police officers and soldiers.

Other factors also impinge on this topic. We will explore:

Whether suicidal behaviour is itself a sign of a mental illness;What role impulsivity plays, as some suicides appear to have no obvious causes;The impacts of the economy and media exposure;Questions of morality – whether suicide is wrong and if there can be such a thing as a rational suicide;The related and contentious issue of assisted suicide, with which politicians and citizens in more and more countries are grappling;Whether a taboo on taking one’s life is helpful or harmful.Most importantly, we will ponder whether or not suicide can really be prevented. We will see that predicting and preventing it is notoriously difficult. That does not stop well-meaning individuals and governments from doing something, on the principle that ‘it’s better to light one candle than to curse the dark’. People and politicians feel better when they are taking positive action of any description, even when they lack proof that it works.

We hope to address these issues systematically and to tease out fact from fiction, pragmatism from hysteria and common sense from nonsense. We rely extensively on the research that has been carried out in this area and assess the evidence before arriving at conclusions. Readers will benefit from the views of a number of experts we interviewed.

This book should be of value to general-interest readers as well as those with a professional interest in the area. By the end, we hope readers will feel more informed and possess a greater appreciation of the breadth and depth of the topic. Compassion has a very important place in any discussion of suicide, but it must be associated with calm rationality. Only then will policy-makers, politicians and societies be able to deal with it in a sensible manner.

Notes

1. Harris, A. ‘No Shame in Feeling Despair’. Irish Times online, 8 September 2014 (cited 5 October 2014). Available from irishtimes.com/life-and-style/health-family/no-shame-in-feeling-despair-1.1916755 2014.

2. The Oxford English Dictionary defines obsession as an idea or thought that continually preoccupies or intrudes on a person’s mind.

3. Anderson, O. Suicide in Victorian and Edwardian England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987.

4. Szasz, T. Fatal Freedom: The Ethics and Politics of Suicide. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1999.

5. Brophy, J. Interviewed by Beattie, D. on 25 March 2014.

6. Emile Durkheim. Suicide: A Study in Sociology. New York: The Free Press, 1897 (1951), p54.

7. Quoted in Schwartz, B. The Paradox of Choice: Why More Is Less. New York: Harper, 2004, p42.

8. Hames, J.L., Ribeiro, J.D., Smith, A.R. and Joiner, T.E. ‘An urge to jump affirms the urge to live: An empirical examination of the high place phenomenon. In Journal of Affective Disorders. 2012; 136 (3): pp. 1114 - 1120.

2.

Suicide: A Brief History

Uncovering historical evidence for the existence of suicide presents difficulties. Such deaths often have been concealed, but all indications are that suicide has existed in diverse societies in all eras. The first Western references to it – in a mix of historical, philosophical and literary sources – date from classical antiquity, between the seventh century BC and the fifth century AD.

In antiquity, the most celebrated case of suicide was that of Ajax. During the Greek war with Troy, Ajax was recognised as the main pretender to Achilles’s position as the greatest Greek warrior. When Achilles was eventually killed, Ajax and his rival Odysseus ensured that Achilles’s body was retrieved for burial. The pair then engaged in several days of competition to claim the prize of Achilles’s armour and, with it, recognition as his rightful successor. Several days of close competition ensued. Odysseus eventually claimed victory and made a remarkable speech. Dejected and humiliated, Ajax saw no alternative but to end his life, which he did with his sword.

A number of examples of group suicides were reported in ancient times, which typically occurred because of military defeats. A mass suicide of 960 Jews is said to have taken place in 73 AD at the cliffs of Masada, which overlook the Dead Sea, during the first Jewish–Roman war. In order to avoid capture by the Romans and certain slaughter, each man killed his wife and children. The men then drew lots to determine which of them would kill each other. Only one actually killed himself, in the same way as Ajax – by falling on his sword.

Most sources from ancient Greece and Rome are very selective, concentrating on the suicides of aristocratic men. Women, slaves and those at the margins of society are all under-represented. Yet, in the figure of Lucretia, Rome provides a female suicide to rival that of Ajax. The daughter of a prominent Roman nobleman, Lucretia was raped by Sextus, the son of Rome’s leader, Tarquin the Proud. Unable to cope with this dishonour, she revealed to her father what had happened, and then plunged a dagger in her own heart. This led to major political upheaval by encouraging the Romans to drive Tarquin and his family out of Rome in 508 BC, paving the way for the establishment of the first Roman republic.1 Fascination with Lucretia’s story would prompt Geoffrey Chaucer and William Shakespeare to pen poems about her centuries later. Titian and Rembrandt are just two of the many Renaissance artists who depicted her death in paintings.

The stories of Ajax’s and Lucretia’s suicides are known to us because of their aristocratic backgrounds. Based on the records of over 20,000 suicides from classical sources from a period spanning some 2,000 years, historian Anton van Hooff calculated a rate of suicide of 0.02 per 100,000 population per annum.2 The modern Greek suicide rate, which is very low by international standards, was 3.8 per 100,000 in 2012. The 190-fold difference in these figures strongly suggests that many ancient suicides went unrecorded. This probably includes most suicides by people from non-aristocratic backgrounds. Van Hooff argues that it is usually because of extraordinary traits that we come to know about the suicides of those from other backgrounds. Unwavering loyalty is one such trait, so we know about the suicides of Cleopatra’s two female slaves, Charmion and Eiras, who chose to die with her.3

The Christian taboo on suicide forms the backdrop for any examination of suicide in the Middle Ages. Suicide did not go away, but uncovering evidence of it became more difficult. People taking their own lives, and those closest to them, often made great efforts to conceal such deaths. A legal code from the French city of Lille in the thirteenth century urged suspicion of suicide when a dead body was found, even when the possibility of suicide was not reported, ‘for he who attempts this desperate act never willingly does it openly’.4

In many European states, the property and assets of those who took their own lives were confiscated. After suicide was made illegal in England in the thirteenth century, those guilty of felo de se (‘felon of himself’ or suicide) forfeited their property to the king, although exceptions were occasionally made if it could be shown the person had been non compos mentis (of unsound mind). Because the monarchy was entitled to take possession of the goods of those who committed suicide, suicides began to be reported to the King’s Bench in England and Wales. Records survive from 1485 until 1714 of cases reported, although these definitely do not include all suicides during that period.5 In France too, until just before the Revolution of 1789, a self-killer’s assets became the property of the king.

In the nineteenth century, technological advances led people to choose newer methods to end their own lives. The advent of the railway introduced the spectre of people throwing themselves in front of trains. Firearms and widely available poisons also become popular suicide methods. New theories and explanations for what drove people to suicide also emerged, and the first serious studies of suicide, including Le Suicide by Emile Durkheim, are from this period.

A rich history of suicide can also be uncovered outside of the West. The ancient sacred Indian texts, the Vedas, referred to suicide as far back as 4,000 BC. They permitted self-killing. Undoubtedly, the most infamous Indian tradition relating to suicide is sati. This custom involves a widow joining her dead husband on his funeral pyre. There are references to sati from the fourth century BC, but it did not grow in popularity until the twelfth century AD, when the practice spread among the Brahmins of Bengal. Sati was often not voluntary – many women were forced into it. The spread of sati at this time may have been linked to a law that introduced inheritance for widows.

The British imperial authorities eventually outlawed sati in 1829, and the persistence of the practice, despite the law, was cited as a justification for the continuation of British rule. Sati continued after Indian independence and occurred sporadically in certain parts of the country in the later twentieth century. The Indian state of Rajasthan introduced its Commission of Sati (Prevention) Act in 1987.

One of the earliest Japanese references to suicide is from the fourth century AD. It concerns the younger brother of the sixteenth emperor of Japan, Nintoku Tennō. Prior to assuming the throne, Nintoku is said to have disputed his own right to become emperor, insisting that his younger brother was more worthy. His younger brother, in turn, insisted that Nintoku should assume the throne. A comical interregnum continued for three years, as each brother sought to outdo the other in his show of modesty. This ended when the younger brother decided he would never be able to overcome Nintoku’s determination. As he believed that the situation was placing the empire in danger, he took his own life.6

More recently, during the Second World War, there is the example of the Japanese kamikaze pilots. They sacrificed their lives for the empire by deliberately crashing their planes into Allied ships and are an example of giseishi or sacrificial suicide. During the Battle of Okinawa, which lasted from April to June of 1945, 4,000 Japanese planes were destroyed by the Allies, and 1,900 of these were kamikaze planes.7 Alert to the existence of kamikaze pilots, ships with anti-aircraft guns usually destroyed their planes prior to the ‘successful’ completion of their missions.

This sacrificial form of suicide, in which enemies are also killed in support of political and military goals, has since then become more familiar to us via suicide attacks by Tamil separatists in Sri Lanka and Islamic fundamentalists in the Middle East and beyond.

Box 2.1 | The Word ‘Suicide’

In spite of including thirteen suicides in his plays, William Shakespeare never actually used the word ‘suicide’. It did not appear in the English language until Sir Thomas Browne’s Religio Medici was published in 1642, although the Oxford English Dictionary dates its first usage to 1651. The German word selbstmord (self-murder) came into usage at roughly the same time. Both words signify sinful acts.

Ancient Greek and Roman descriptions of suicides did not have such negative connotations. The most commonly used ancient Greek word, authocheir, means to act with one’s own hand. For anti-psychiatrist Thomas Szasz, the emergence of the noun ‘suicide’, to be distinguished from the verbs and verbal nouns that were used by the Greeks and Romans, indicated a dramatic shift, from viewing suicide as a self-determined act towards viewing it as a deed for which the person who kills himself may not be responsible.8

The English language has much less flexibility than other languages when it comes to describing suicide. English has no words, for instance, that allow speakers to identify forms of suicide that we might approve of. The Japanese word jisatsu implies a negative act, but other words – such as jiketsu and jisai – refer to an honourable act carried out in the public interest.

Attitudes and Reactions to Suicide

Signs surround suicide hotspots nowadays, urging those thinking of killing themselves to reconsider and to make contact with crisis services. This reflects the compassion now shown to those who see suicide as the best solution to life’s problems and the obligation felt by society to prevent suicide. After an unsuccessful suicide attempt, care, kindness and help with overcoming the distress that sparked the suicidal impulse are typically offered. This has not always been the attitude towards suicide.

Although suicide has always been present, attitudes and reactions to it have by no means been constant. Medieval Western societies approved of severe punishments for suicide attempters and the grisly treatment of suicide fatalities; the mutilation of corpses was common. In ancient Greece and Rome on the other hand, suicide could sometimes be represented as a thing of beauty. Seneca, a Roman Stoic philosopher and statesman, reacting to the suicide of the incorruptible Roman politician and enemy of Caesar, Cato the Younger, said: ‘Never could Jupiter have seen a fairer thing on earth than Cato’s suicide.’9 Seneca himself went on to die by suicide after being implicated in a plot to kill the emperor Nero.

Classical antiquity is the period in Western history when approval of and admiration for self-killing can be unearthed, which contrasts most starkly with medieval and modern attitudes. In ancient Greece, the suicides of Ajax and Lucretia illustrate what Anton van Hooff describes as a ‘shame culture’, in which heroes paid plenty of attention to how they were viewed by others.10 Humiliated and dishonoured, both Ajax and Lucretia knew that suicide would gain them respect from their peers. Such was the seriousness with which suicide was viewed that ancient Athens even legislated for a form of assisted suicide. Permission to kill yourself, and the means to do it with poisonous hemlock, could be provided by the Athenian authorities if you successfully pleaded your case before the Senate.

Suicide did not always meet with the approval of the Greeks, however. Aristotle mentioned punishments imposed on those who had attempted suicide, including fines and losses of political rights. He and Plato considered suicide in a number of their works, and they both generally condemned it. Aristotle believed that a person who displayed courage in the face of death was noble, and so, by extension, suicide was the act of a coward. Because the law did not allow for suicide, it must be forbidden, Aristotle argued; the self-killer was acting in an unjust manner towards the state. Plato’s objection to suicide centred on his view of man as belonging to the gods. During our lives, we act like guards on behalf of the gods and are not allowed to leave our posts whenever we see fit, he believed. In his Phaedo – which details the death of his teacher, Socrates, after consuming hemlock – Plato stated clearly that suicide was not lawful. In Laws, he outlined appropriate punishments. His ideal state would have punished self-inflicted death with burial ‘ingloriously on the borders … in such places as are uncultivated and nameless’, with ‘no column or inscription’.11 He allowed, however, that some suicides could be justified, making exceptions for those coping with extreme misfortune or intolerable shame.

Roman law recognised that many suicides were rational and therefore had to be legislated for. Reasons that might lead a man to kill himself rationally included pain or sickness, a fear of dishonour and taedium vitae (weariness of life), which was probably akin to what we now call depression. Among those not allowed to kill themselves were slaves and soldiers. This, of course, had nothing to do with any moral or religious disapproval of suicide and everything to do with the bottom line.12 Slaves were the property of their masters and soldiers belonged to the state. Any societal approval of suicide that existed among the ancient Greeks and Romans would not survive the Christian prohibition on suicide, which was most strongly associated with Augustine of Hippo.