6,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 7,49 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 7,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: WriteLife Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

On August 6, 1945, 22-year-old Kaleria Pachikoff was doing pre-breakfast chores when a blinding flash lit the sky over Hiroshima, Japan. A moment later, everything went black as the house collapsed on her and her family. Their world, and everyone else's, changed as the first atomic bomb was detonated over a city.

From Russian nobility, the Palchikoff's barely escaped death at the hands of Bolshevik revolutionaries until her father, a White Russian officer, hijacked a ship to take them to safety in Hiroshima. Safety was short lived. Her father, a talented musician, established a new life for the family, but the outbreak of World War II created a cloud of suspicion that led to his imprisonment and years of deprivation for his family.

After the bombing, trapped in the center of previously unimagined devastation, Kaleria summoned her strength to come to the aid of bomb victims, treating the never-before seen effects of radiation.

Fluent in English, Kaleria was soon recruited to work with Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s occupation forces in a number of secretarial positions until the family found a new life in the United States.

Heavily based on quotes from Kaleria's memoirs written immediately after World War II, and transcripts of United States Army Air Force interviews with her, her story is an emotional, and sometime chilling, story of courage and survival in the face of one of history’s greatest catastrophes.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

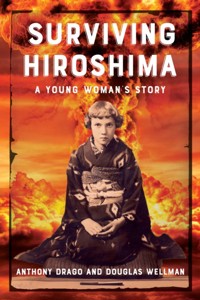

Surviving Hiroshima: A Young Woman’s Story

© 2020 Anthony Drago and Douglas Wellman. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or digital (including photocopying and recording) except for the inclusion in a review, without written permission from the publisher.

Published in the United States by WriteLife Publishing

(An imprint of Boutique of Quality Books Publishing Company)

www.writelife.com

978-1-60808-236-0 (p)

978-1-60808-237-7 (e)

Library of Congress Control Number 2020938572

Book design by Robin Krauss, www.bookformatters.com

Cover design by Rebecca Lown, www.rebeccalowndesigns.com

First editor: Michelle Booth

Second Editor: Kathy Bock

Portrait of Kaleria Palchikoff Dec. 1945. Under the Mushroom Cloud in Hiroshima. Artist: 1st. Lt. Richard M. Chambers, U.S. Army. Courtesy, United States Air Force Art Collection.

Palchikoff Marquis Coat of Arms - Awarded in 1620.

Praises for Surviving Hiroshima, Anthony Drago, and Douglas Wellman

Surviving Hiroshima is an unforgettable human drama and a moving memory of Kaleria Palchikoff Drago who at 24 years of age was living with her family in Hiroshima when the atomic bomb was dropped on 6 August 1945. Her personal accounts of that experience and afterwards for her, her family, and their Japanese neighbors and friends are riveting, inspirational and often sad. As her son and author Anthony Drago writes, “It’s a story of hope and perseverance that others may model when life turns against them.”

— Lieutenant General Robert Ord, U.S. Army Retired, Former Commander of U.S. Army Pacific

Drago and Wellman weave an unforgettable, true, and astonishing story about a young woman who with great dignity and determination survives the horrors of the Hiroshima holocaust and the cruelty of war. A descendant of White Russian nobility, Kaleria Palchikoff finds herself and her family in a desperate situation, fleeing the Bolsheviks from the Russian Far East in 1922, making their way across the Sea of Japan in a hijacked freighter, and eventually becoming unlikely immigrants in pre-war Hiroshima, Japan. Strikingly accurate with its in depth research and written in a fluid style that draws in the reader, it’s a compelling account of how hibakusha Kaleria lived, grew up, mingled with Japanese neighbors and friends, then survived, thrived, and matured as a hero, wife, and mother who eventually settled in America and raised her family. For an insightful perspective and a rare glimpse of WWII history, the war’s effect on survivors’ families and children, and the hellish story and aftermath of the August 1945 Hiroshima bombing, this is an essential book that you won’t put down.

— Robert Simeral, Captain, U.S. Navy (Ret.)

These riveting autobiographies of Tony Drago’s White Russian Orthodox Christian Aristocratic Grandfather and Molokan Christian Grandmother with their family of three children, the only English speaking witnesses who survived the horror of the 1945 Hiroshima atom bomb explosion are so spellbinding that they transport the reader onto the path of history which affirms the belief, truth, and love by which this family lived. When hope seemed lost and the future heralded only suffering, faith in God and His Mercy was their answer. They invite us to use our free will to call on our Creator to guide us all—“I will be with you always” . . . I was in Hell—Hiroshima,” as Kay said. These life journeys are history, now recorded in Hiroshima and Washington DC for all to see and behold.

— A.B. Janko MD

Dedication

For my wife, Kathy—you are and always will be my greatest work of love.

— Anthony Drago

For Deborah—the love of my life and my exceptionally patient wife.

— Douglas Wellman

Table of Contents

About the Book

Authors’ Note

Chapter One: It’s Hiroshima

Chapter Two: The War before the War

Chapter Three: Escape to the Rising Sun

Chapter Four: Day of Infamy

Chapter Five: Oppression

Chapter Six: Fighting Back

Chapter Seven: Secret Mission to Tawi Tawi

Chapter Eight: Deadly Decision

Chapter Nine: A Blinding White Light

Chapter Ten: Unparalleled Devastation

Chapter Eleven: Struggle for Survival.

Chapter Twelve: I Must Do Something

Chapter Thirteen: All for One and All for Nothing

Chapter Fourteen: A One in a Million Chance

Chapter Fifteen: Who Is That Girl?

Chapter Sixteen: Two GIs in a Jeep

Chapter Seventeen: In the Spotlight

Chapter Eighteen: Return to Ground Zero

Chapter Nineteen: Closure

The Family

Afterword

Acknowledgments

Bibliography

About the Authors

About the Book

This book relies heavily on the personal reminiscences, both verbal and written, shared by Kaleria Palchikoff Drago with her son, Anthony. Some of her memories were written immediately after the war, and others years later. Anthony and co-author Douglas Wellman have quoted directly from the written works whenever possible.

Authors’ Note

In 1945, the United States Army Air Forces conducted a postwar analysis of the effects of their bombing raids entitled The United States Strategic Bombing Survey. In preparing the Pacific War document, Air Force personnel recorded audio interviews with survivors of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings and later transcribed the recordings. Kaleria Palchikoff was the only English-speaking atomic bomb victim interviewed. Two audio recordings of her exist, as well as thirty pages of transcription. Since Miss Palchikoff was responding spontaneously to questions asked of her, her answers sometimes contained abrupt changes of thought or corrections of grammar as she considered and responded to questions without having any preparation. We have chosen to quote from the transcript verbatim, rather than rewrite it, to preserve her feelings and emotions as accurately as possible.

CHAPTER ONE

IT’S HIROSHIMA

Tinian—August 6, 1945

In the context of planet Earth, Tinian isn’t much. With just thirty-nine square miles of vegetation clutching a limestone atoll amidst coral reefs, the tiny spit of land in the vast Pacific Ocean seems an unlikely host for a world-shattering event. Under the successive rules of Spain, Germany, and Japan, Tinian was not so much a destination as it was a stopping point on the way to a destination. It was little more than a place for sailors to resupply on their way somewhere else. Most people had never heard of it. That was about to change.

At zero hundred hours local time, seven tense, twelve-man bomber crews of the 393rd Bomb Squadron, 509th Composite Group, gather in the crews’ lounge adjacent to the island’s short airstrip for their preflight briefing. They are about to do something big, they know that, but that’s about all they know. They know their target will be Japan, but exactly where in Japan is secret. They know they are carrying a special weapon, but the exact type is also secret. Secrets make people uneasy. Cigarettes and coffee help, but not much.

As Colonel Paul Tibbetts, Jr., Special Bombing Mission No. 13’s commander, begins to speak, he has no concerns about holding the crews’ attention. These men were handpicked as among the best in their military occupation specialties, and their character and experience are exemplary. They’re ready to do a job and are anxious for Tibbetts to tell them exactly what that job will be. Tibbetts tells them a lot, but not everything. They will have to wait for the rest of the details until they are in the air. Colonel Tibbetts will personally fly the modified B-29 Superfortress bomber, which he has named Enola Gay, after his mother. Their call sign for the flight, “Dimples 8-2,” certainly gives no hint of their deadly payload.

The Enola Gay will drop the first atomic bomb ever used in war.

Three other Superfortresses named Straight Flush, Jabbit III, and Full House will leave one hour ahead of the Enola Gay to scout weather conditions at the designated target cities of Hiroshima, Kokura, and Nagasaki. Target recognition is especially critical on this mission, so it has been decided that each target must be identified visually, rather than by radar alone. The preceding day, air force meteorologists forecast favorable weather for the mission, but nothing will be left to chance. Any potential target obscured by clouds will no longer be considered viable. Tibbetts will make final target selection in the air. Two more B-29s will join the Enola Gay over the target: The Great Artiste, carrying scientific instruments to measure the blast and its effects, and an unnamed B-29, (later named Necessary Evil), assigned for strike observation and photography. They will take off immediately after the Enola Gay. A seventh B-29, Big Stink, will also fly part of the mission as a back-up escort aircraft in the event one of the bombers has a mechanical failure and has to abort the mission.

With the briefing completed, several trucks pull up to the crew lounge shortly after 1:00 a.m. to transport the flight crews to their staged aircraft. The historical importance of this flight is not lost on anyone. Camera crews are gathered on the floodlit tarmac to record the final moments before takeoff. At 2:20 a.m., Tibbetts and his crew pose in front of the Enola Gay for a last, pre-mission group photo. After the shutter clicks Tibbetts turns to his crew and says, “Okay, let’s go to work.” With that, they hoist themselves into the belly of the silver beast.

Tibbetts slips into the pilot’s seat, grabs his checklist, and begins final preparations before engine start. To his right is copilot Captain Robert Lewis. Lewis isn’t entirely happy this dark morning. In fact, he is bitterly angry. Lewis had previously been assigned to pilot this aircraft and is indignant about being replaced by Tibbetts. To add insult to injury, Lewis was shocked to see the words Enola Gay painted on the nose of what he considered his aircraft, and he shared his feelings in a furious outburst with everyone within earshot. Pushing his anger and hurt feelings aside, Lewis gets down to work.

The Enola Gay is a special version of the B-29, a Silverplate specification, which designates that it has been modified for a unique role as a nuclear weapons delivery aircraft. The Enola Gay’s atomic bomb payload, known as Little Boy, presents significant challenges to the aircraft and crew. Little Boy has, in one bomb, the explosive power of two thousand Superfortresses armed with conventional bombs. But Little Boy is anything but little. At ten feet long, twenty-eight inches in diameter, and 9,700 pounds, it is a monster in the world of ordnance. To meet its special task, the Enola Gay has been beefed up with modified bomb bay doors, a special bomb release system, fuel-injected engines to boost it into the air, and reversible pitch propellers to stop it when it comes back down. Even with the modifications, there is still one major concern: Enola Gay is unusually heavy and the airstrip at Tinian is uncomfortably short. What will happen if Tibbetts can’t get the bird in the air before he runs out of airstrip and crashes with an atomic bomb on board? It isn’t much of a question, because everyone knows the answer: Tinian, and everyone on it, will be incinerated.

The responsibility for ensuring that Little Boy explodes over Japan—and not before—falls squarely on the shoulders of weaponeer Navy Captain William “Deak” Parsons. Because of the possibility of a disastrous takeoff, it has been suggested that Parsons arm Little Boy in the air. While this may sound comforting to those on the ground, it doesn’t make Parsons’s job any easier. Arming the bomb is a delicate procedure that he has practiced many times, but the thought of performing this maneuver in the cramped bomb bay of a bouncing aircraft is concerning. At first Parsons is hesitant to arm the bomb in the air; however, he has personally witnessed four B-29s crash and burn on takeoff, so he has firsthand knowledge of the risk involved. After careful consideration, he comes to the conclusion that aerial arming is the better option. Tibbetts and Lewis will have to hold the Enola Gay as steady as possible during the procedure. Hopefully, they won’t hit turbulence. Parsons will have to be painstakingly careful. They all have the skill, but a certain amount of luck will be appreciated.

At 2:27 a.m., it’s time to get down to business. Tibbetts slides his cockpit window open and motions for the ground crew to stand clear. A photographer yells up to him, asking him to wave for the camera. Tibbetts complies with a reflexive smile, belying the seriousness of the moment. He slides the window closed and begins the engine start sequence. Eighteen minutes later he turns to Lewis and says, “Let’s go,” as he pushes the throttles forward. The overloaded Enola Gayslowly begins to roll forward. It needs almost every foot of runway to get into the air, but fortunately, not more. The bomber is six hours from its historic destiny.

The Enola Gay is a big aircraft and needs a big crew, twelve men in all. Navigator Captain Theodore Van Kirk will be responsible for getting them to the target. Major Thomas Ferebee, bombardier, sitting all the way forward in the Plexiglas bubble in front of the pilot and co-pilot, will be responsible for dropping Little Boy when they get there. The rest of the crew will be responsible for keeping the airplane safely in the air. Technical Sergeant Wayne Dusenberry, flight engineer, and Sergeant Robert Schmard, assistant flight engineer, are assigned to monitor the aircraft’s four engines and complex hydraulic and electrical systems. Sergeant Joe Stiborik mans the radar screen. Private First Class Richard Nelson is at the controls of the radio, and Lieutenant Jacob Beser is responsible for radar countermeasures. Second Lieutenant Maurice Jepson is the assistant weaponeer who will assist Captain Parsons with arming the payload. To the rear of the aircraft Staff Sergeant George “Bob” Caron, tail gunner, will keep unfriendly visitors from sneaking up on them. Caron will have one advantage over the rest of the crew. He will be the only one facing the drop zone after Little Boy is unleashed. Whether it is a success or a failure, Caron will be the first to know.

The B-29 is among the most advanced aircraft of its era. One of its advantages over previous aircraft is its pressurized cabin. However, the bomb bay cannot be pressurized because the doors have to open over the target. To solve this problem, the aircraft’s designers created pressurized compartments in the cockpit and tail sections of the airplane, leaving the waist—the center section of the aircraft—unpressurized. The two pressurized sections of the aircraft are connected by a pressurized tube that the crew can crawl through.

After takeoff, but before the aircraft is pressurized, Caron crawls forward to the waist section to stretch his legs. Once the aircraft is pressurized, he will be stuck in the tail for the remainder of the mission. At this point, Colonel Tibbetts emerges from the tube to have a few personal words with the crew. They chat briefly and then Tibbetts asks them if they have any idea what kind of weapon they are carrying. Caron asks if the weapon was the result of a chemical process. Tibbetts says no. Caron asks if the weapon involves physics. Tibbetts nods that it does. After their few minutes together, Tibbetts enters the tube to crawl back to the cockpit, but Caron grabs him by the foot. Tibbetts scrambles back quickly, thinking there is a problem, but it’s just one last question. “Colonel,” Caron asks, “are we splitting atoms this morning?” Tibbetts nods his head yes. Now they know.

At 2:55 a.m., Captain Van Kirk begins his navigator’s log. The Enola Gay and its companion aircraft will not be setting a direct course for Japan, but instead flying independently to the island of Iwo Jima where they plan to rendezvous shortly before 6:00 a.m. Little Boy is to be armed on the first leg of the mission, so at 3:00 a.m. Captain Parsons signals Tibbetts that they are about to start the procedure. Parsons and Lieutenant Jepson crawl into the cramped bomb bay next to the four-and-a-half-ton weapon to begin the delicate process of converting a highly complex, but inert, physics project into the deadliest weapon ever envisioned by man. Ironically, the detonator is comprised of gunpowder, man’s first superweapon.

The bomb detonation mechanism is similar to that of a gun. One hundred forty pounds of uranium-235 is divided between the front and rear of the cylindrical bomb casing. In the tail of the bomb, the powdered explosive is seated behind the uranium. When ignited by an electrical charge at the proper altitude, the exploding powder will push the uranium “projectile” through the bomb like a bullet through a gun barrel until it strikes the uranium “target” in the nose of the bomb. The collision will set off a nuclear chain reaction with a devastating result.1

Parsons carefully seats the detonator in the weapon. To prevent an accidental detonation during this process, there are three green plugs that act similar to a safety on a firearm. The green plugs interrupt the electrical circuit in the detonator so no electrical pulse can ignite the powder. When Parsons is confident that the detonator is inserted properly, he turns to Lieutenant Jepson for the final step. Jepson removes the green plugs and replaces them with red plugs, which do not block the circuit. The bomb is now ready. Jepson keeps the green plugs as a souvenir.

Leg one of the mission is uneventful. The navigators of the three B-29s locate the eight square miles of Iwo Jima out of the vast Pacific Ocean without problem. Iwo Jima looks peaceful from nine thousand feet, a far cry from the blood-soaked, volcanic rock that claimed over 25,000 American and Japanese lives only five months earlier and left nearly twenty thousand more US troops wounded. Relatively few Japanese had been wounded at that time since the Japanese soldiers preferred to fight to the death, a characteristic that did not go unnoticed by those planning the invasion of Japan. If the Japanese would rather die than surrender a tiny island, what will they do when their homeland is attacked? This is another question for which the answer is apparent to all.

With The Great Artiste and Necessary Evil in formation, the flight climbs to an altitude of 30,700 feet, and the aircraft are pressurized. The final leg of the mission will be roughly 750 miles, but at this point the navigators are unable to calculate an absolutely precise course. The target is dependent upon weather conditions, and until the three weather reconnaissance aircraft report back, the destination is still unknown. Hiroshima has been designated as the primary target, with Kokura and Nagasaki as alternative targets. In the skies over Japan, Straight Flush, Jabbit III, and Full House draw little attention from the Japanese military as they overfly the cities. The island battles in the Pacific, while slowing their enemy down, have seriously depleted Japan’s military resources. The fall of Okinawa six weeks earlier has given the Americans a strong offensive foothold just one thousand miles from the Japanese mainland. Japan’s military leaders know they will need every available aircraft and every gallon of aviation fuel to repel the invasion that is inevitably coming. American carpet-bombing airstrikes have wrought havoc over Japanese cities. Japanese fighters have gone up to meet the large B-29 bomber formations, but they have paid little attention to flights of one or two aircraft, assuming they are merely photo reconnaissance.

Colonel Tibbetts keys open his microphone and reveals the final secret to anyone on the crew who has not already figured it out. “We are carrying the world’s first atomic bomb.” It’s time to get serious. The crew does a final check of personal equipment, adjusting their flak jackets and parachutes. Each man has been equipped with a special piece of gear just for this mission: dark Polaroid goggles to protect their eyes from the brilliance of the atomic blast.

At 8:09 a.m. Tinian time, the air raid sirens in Hiroshima begin to wail and soon the civilian and military population of the city hear an unfortunately common sound in the sky, the four-engine rumble of a B-29. As they look upward, they can clearly see Straight Flush. More importantly on this day, Straight Flush can clearly see them. Pilot Claude Etherley sends a coded message to the Enola Gay: “Y-3, Q-3, B-2, C-1,” indicating that cloud cover over Hiroshima is less than 3/10s.

Tibbetts keys his mic again and translates for the crew: “It’s Hiroshima.”

With the departure of Straight Flush, the “all clear” siren is sounded in Hiroshima and the unknowing population returns to its normal morning routine. Reconnaissance flights over Japanese cities are common, and the presence of a few aircraft doesn’t cause much concern; it’s the large-scale attacks that get people worried. Just the previous night, the skies over southern Japan were filled with American raiders. Japanese radar screens lit up with blips as 261 aircraft headed for Nishinomiya; 111 aircraft headed for Ube; 102 aircraft headed for Maebashi; 66 aircraft headed for Imbabura; and 65 aircraft headed for Saga. It’s the big raids that cause fear, not this annoyance this morning. After all, how much damage could one B-29 do?

Fifteen minutes away, over the island of Shikoku, approaching the Iyo Sea, the Enola Gay sets up its bombing run. Navigator Van Kirk has made his final adjustments to guide the aircraft to the target, but the fairly clear skies are a big help. Visual target recognition is critical on this mission. The aim point has been designated as the Aioi Bridge, a T-shaped structure that spans the Honkawa and Motoyasu Rivers near downtown Hiroshima. The bridge makes an ideal aiming point, since its distinctive shape is easily discernible, even from an altitude of over thirty-one thousand feet. Van Kirk gives the crew a ten-minute warning. On the ground the approaching flight of three B-29s has been detected, but no fighters take to the air to oppose it. Hiroshima radio announces the incoming flight to its listeners, but these warnings have become routine. For the most part, it is business as usual on a sunny morning.

Three minutes to the aim point, Tibbetts turns control of the Enola Gay over to bombardier Major Ferebee. He enters the final data into his sophisticated Norden bomb site, which will fly the plane to the target, and prepares to initiate a sixty-second timing sequence that will automatically release Little Boy over the drop site. Tibbetts asks the crew for visual target verification. Anyone with a view of the drop zone verbally acknowledges that they see the Aioi Bridge. This is no time for mistakes.

The Great Artiste and Necessary Evil break formation with the Enola Gay. They will not overfly the city for the bombing run, but will stay four to five miles away to execute their specific missions. With seconds remaining before the drop, The Great Artiste releases scientific instruments attached to parachutes that will float to the ground during the blast and radio back information to determine the bomb’s yield. Necessary Evil has its cameras ready to record the blast. In the back of the Enola Gay, Bob Caron has a K20 aerial camera to photograph the target as the Enola Gay pulls away from the blast site—and a wire recorder that he will use to describe what he sees. What he will not do is fire his guns. There are still no Japanese fighters in the sky to hunt them and the Japanese antiaircraft artillery is silent, apparently conserving ammunition for an anticipated bigger event.

At 09:15:15 a.m. Tinian time—08:15:15 a.m. Hiroshima time—the bomb drop sequence counts down to zero and Little Boy falls free from the bomb bay. Major Ferebee announces, “Bomb away,” but everyone already knows that. Suddenly no longer struggling with its nearly ten-thousand-pound load, the Enola Gay has leaped upward, jolting the crew. Tibbetts immediately pulls the aircraft into a 155-degree right turn to put as much distance as possible between them and the blast site. They will have some time to make their escape. It will take Little Boy forty-four seconds to fall to its designated detonation altitude of just under two thousand feet.

In forty-four seconds, the future of warfare will be inalterably changed.

In forty-four seconds, tens of thousands of people will have their lives shattered in an instant.

In forty-four seconds, a twenty-four-year-old Russian émigré, Kaleria Palchikoff, will be in the center of a horrendous conflagration never before unleashed in human history.

Kaleria Palchikoff was my Mother.

Notes

1. Stockbauer, “The Designs of Fat Man and Little Boy.”

CHAPTER TWO

THE WAR BEFORE THE WAR

My mom should have had a fairytale life. She came from a long line of Russian nobility, a family for centuries steeped in honor and privilege. Noble blood flowed through her veins and a privileged place in society should have been her birthright. But, when Kaleria Palchikoff was born on June 20, 1921, in Vladivostok, the Russian aristocracy was under attack. The assumption that leadership and wealth were a birthright was under assault from a stratum of society that had been neglected and often abused. The aristocratic lineage that should have ensured her a position of comfort and wealth now made her and her family the target of radicals and reformers bent on tearing down the czarist government and anyone attached to it. My mom should have had a fairytale life, but she didn’t.

Like most children, fairy tales were part of my very early childhood. Other children’s parents would read to them from children’s books, like Aesop’s Fables. The fairy tales my mother told me—stories of nobility and bravery—came from my family history passed down through the centuries. Unlike most storybook fairy tales, ours did not always have a happy ending.

As a small boy growing up in New Jersey and California in the 1950s, it was hard for me to envision a time and place so different from my childhood surroundings. That was the period of the Cold War, and the news media rarely mentioned anything good about Russia, let alone the rich cultural and artistic history of the country. My mom knew better, of course, and was proud of her family heritage. Having had the incredible misfortune to lose virtually everything twice in her young life, she had few physical mementos to share with me, but her memories were abundant and rich. They were the best gifts she could give a young boy, and my imagination ran wild. She was proud of her family and delighted in sharing that pride with me through stories of her youth and family history. I was equally delighted to hear the stories, especially the way she told them. My mom had lost the accoutrements of nobility, but not the character of it. Her parents raised her in the long tradition of their aristocratic family, even as they ran for their lives. Decades later when she became Kay, the American housewife, she still maintained a noble bearing that set her apart.

When I became an adult and had a broader appreciation for history, particularly that of my family, I asked Mom to put her recollections down on paper for me so that I could know as much about my roots as possible and pass the information on to my own children. Over the course of a few years, she did just that. My mom was educated, articulate, and wrote very well, so she is directly quoted throughout this book. She also left numerous audio recordings, some of which are accessible on the Internet. Her English and diction were flawless.

Having the information was one thing; doing something with it turned out to be quite different. I am not a writer. I had a long career in law enforcement, which I know very well, but writing and publishing were a mystery to me. That changed when I was introduced to Douglas Wellman, a writer with a passionate interest in World War II. He joined with me to create this book because it is more than just a family story; it is a firsthand account of an event that remains a turning point in human history. My mom was well aware of the historical significance of her story, but it was the family memories that were most dear to her. Those memories, along with the few pieces of salvaged family memorabilia that my grandparents passed down to her, formed the foundation of her self-identity. In her memoir, she wrote:

It gave me a sense of belonging knowing my heritage was true and I was in need of this to strengthen myself against the fact that my family and I were immigrants and had no country. It also was the fact that we could get no asylum from the strife of war in case there existed such a thing in the future. So, these things were always foremost in our minds, but due to the confidence, faith and hope that my parents instilled in me I always believed that everything was going to be okay. I was one of the lucky kids that had something concrete to hold onto because my parents talked to us and showed us things that confirmed to me that my ancestors indeed were upholding citizens of Russia and that I was part of all that history.1

One of the advantages of the aristocracy is that history records their deeds. The average person may pass through life and be forgotten in a generation or two, but the acts of nobility—both good and bad—are recorded for posterity. My mom could trace our family history back four hundred years, a record that displays unwavering family loyalty to the czarist regimes. On my grandfather’s side, one family member was awarded the title Pomeschik—Landowner—by a czar for his extraordinary acts of service. The land, title, and family crest were handed down from generation to generation. My mom took great pride in her lineage that was rooted in honor, loyalty, and service. She passed that pride on to me in her stories.

Wars, purges, and the deliberate destruction of historical documents deemed uncomfortably truthful by incoming political regimes have left some gaps in our family history, yet the evidence of government service and loyalty is very clear in records that remain, as well as the family stories passed down through the generations. In an unexpected bit of good luck, while researching my family history I came in contact with Toni Turk, an authority on Russia, an accredited genealogist, and amazingly, a former student of my grandfather’s at the Army Language School, now known as the Defense Language Institute. His help has been invaluable in tracing my family history.2

My great-great-granduncle, Nikolai Evgravich Palchikoff, was a wealthy estate holder in the village of Nikolaevka, Menzelinsk, Russia. After he graduated from Kazan University, he engaged in a lifelong study of Russian folk music, putting this largely oral, choral music tradition on paper and preserving it. Upon his death in 1838 he was acclaimed as “one who followed in the footsteps” of Aleksandr Pushkin, long regarded as “the god of Russian literature.”3 The estate was passed on to my great-grandfather, Alexander Palchikoff, who inherited Nikolai’s love of music and shared it with his wife, Maria. My grandfather, Sergei Alexandrovich Palchikoff, was born February 25, 1893, in Nikoleava and was raised along with one brother and one sister. The family was aristocratic and firmly aligned with Czar Nicholas. In an earlier time, the family was granted the title of marquise in France, as well as land. The coat of arms that symbolized this status shows a marquise crown, with a Star of David and an eagle. The symbols and the colors used in the coat of arms are interpreted to mean Defender of the Faith. If ever there was an appropriate title, this was it. Deep faith was the backbone of my family for generations, and a central component by which Mom survived all that life would one day throw at her.

My family’s position in the Russian aristocracy endured in various family lines for half a millennium. In 1613, the Romanov family ascended to rule Russia and remained in power until they were deposed in the Russian Revolution of 1917. As part of the aristocracy, my family’s lives were comfortable, but that was not the case for all. In my grandfather’s youth, there was a great divide between the “haves” and the “have-nots.” While my family lived in relative luxury, the working class did not have much to look forward to other than more work. There was little or no opportunity for those of little means to work their way toward anything we would refer to as a middle class, and certainly not to wealth. To the contrary, a system of feudalism was still in place in which workers served as serfs—little more than slaves. These practices were being abolished around the world, but Russia lagged behind in social reforms. In 1861 Czar Alexander II emancipated the serfs and undertook various policies to make life better for the poor. For his reformist efforts he was assassinated in 1881. His line of successors, Alexander II, Alexander III, and Czar Nicholas II did not take the same risk; they revoked the reforms for the poor. Predictably, the poor became militant.

While my grandfather was still young, many working-class Russians began forming political parties. One of these parties, the Bolsheviks, under the leadership of Vladimir Lenin, grew in popularity and became a major voice of the workers. The czar had the military at his disposal and the aristocracy, like my family, firmly on his side. Had Russia’s problems remained strictly internal he might have kept a lid on the boiling discontent; however, a series of foreign entanglements led to an increasingly unhappy citizenry. Russia found itself contesting control of the territories of Manchuria and Korea with the Empire of Japan, which resulted in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904—a military disaster for Russia that inflamed public sentiment against the czar. To make the situation worse, in January 1905, a group of workers staged a demonstration by marching to the czar’s winter palace in St. Petersburg. Although they were peaceful, the czar’s Imperial Guard opened fire on them, killing over one hundred of the protestors. The outrage for what came to be known as Bloody Sunday manifested in a series of strikes, demonstrations, student uprisings, and even political assassinations. Czar Nicholas retained power over the people, but he was quickly losing their support.

There is absolutely no question of how my family felt about these emerging workers’ political parties: They were against them. My family was unwaveringly loyal to the monarchy. What I do not know is whether or not they recognized these groups as a real threat. Did they believe the Romanovs invincible? Did they think these new political parties—which they may have viewed as little more than slightly organized mobs—could possibly be a threat to the stability of the government? Unfortunately, I have no records of my family’s conversations on the subject, so I will never really know. What is undeniable is that my grandfather and his siblings were carefully schooled and groomed as though the aristocracy—and their role in it—would go on forever.

Participating in the arts was expected of those in my family’s economic station, and this period was something of a golden age for Russia. This was a time when literary lights such as Anton Chekhov, Leo Tolstoy, and Fyodor Dostoyevsky created works that have become classics. In the world of music, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky composed Swan Lake, The Sleeping Beauty, and The Nutcracker. The symphony and opera were a significant part of the aristocratic social scene, and music was particularly important to my family. My grandfather Sergei’s mother, Maria Poppov, was a skilled pianist. Keeping with family tradition, and to help her indulge her passion for music, Sergei’s father purchased a music school for her where she served as principal and used her talents to teach the young people of their town. (In 1930, after their escape from Russia, she won first place at the International Music Festival in Shanghai playing the piano at the age of eighty.) My grandfather inherited not only his mother’s passion for music, but also her talent for it. He mastered eight instruments and had a particular love for strings. His uncle made a custom violin for him, which was his prized possession. He did not know it at the time, but this dedication to music and that violin would one day become a critical element in the family’s survival.

With my family’s social station, a high level of education was expected. Although his passion was music, Sergei enrolled in law school. From what my mom told me, it is not clear whether a law career was Sergei’s dream or his father’s. Maybe he did not want to be a lawyer or a public official; maybe he would have preferred to be a musician. I do not know. In the end it did not matter. Political events would soon destroy all dreams, no matter whose they were.